Charles Scott (governor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Scott (April 1739October 22, 1813) was an American military officer and politician who served as the

governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-e ...

from 1808 to 1812. Orphaned in his teens, Scott enlisted in the Virginia Regiment in October 1755 and served as a scout and escort during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

. He quickly rose through the ranks to become a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. After the war, he married and engaged in agricultural pursuits on land left to him by his father, but he returned to active military service in 1775 as the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

began to grow in intensity. In August 1776, he was promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

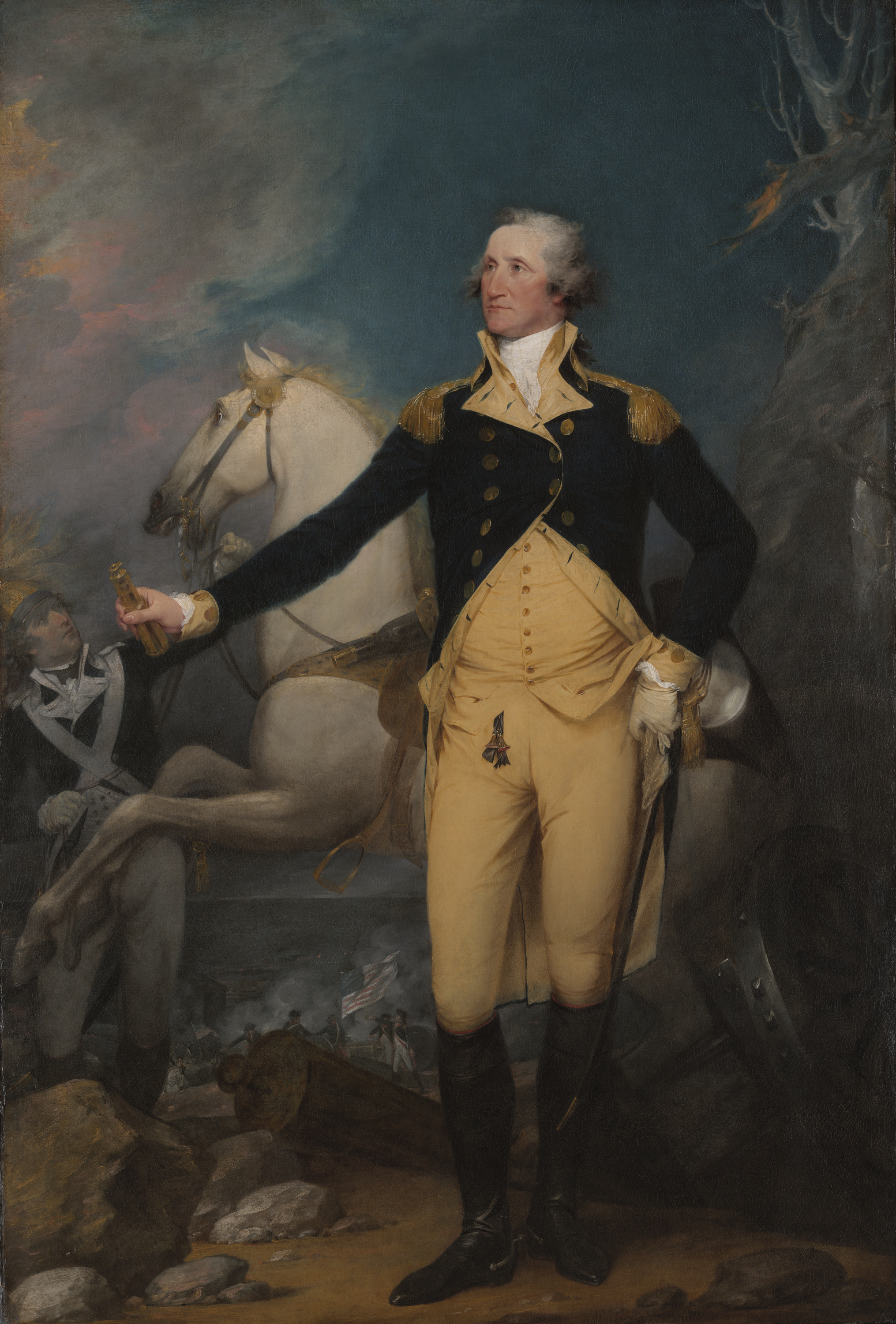

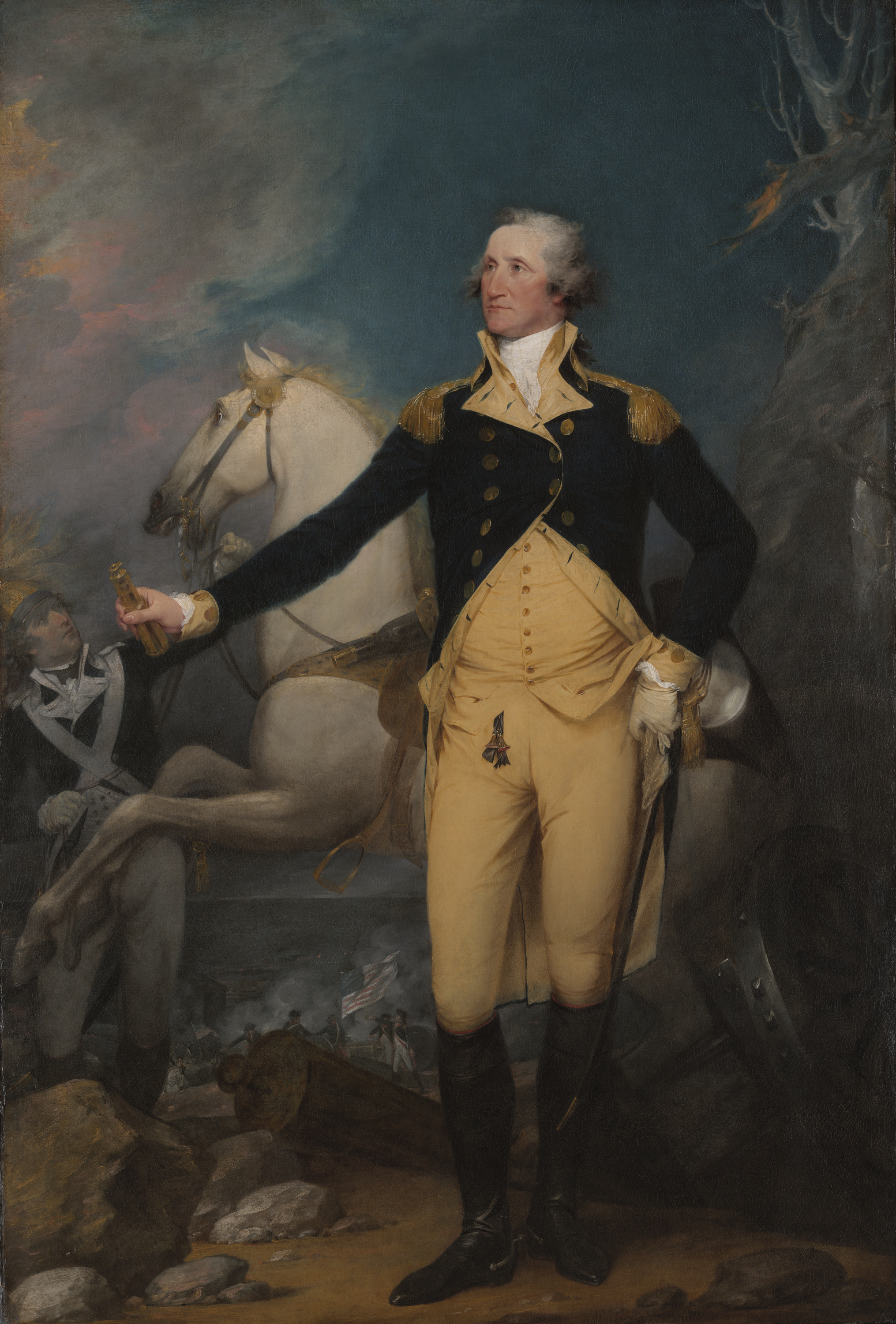

and given command of the 5th Virginia Regiment. The 5th Virginia joined George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

later that year, serving with him for the duration of the Philadelphia campaign

The Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) was a British effort in the American Revolutionary War to gain control of Philadelphia, which was then the seat of the Second Continental Congress. British General William Howe, after failing to dra ...

. Scott commanded Washington's light infantry, and by late 1778 was also serving as his chief of intelligence. Furlough

A furlough (; from nl, verlof, " leave of absence") is a temporary leave of employees due to special needs of a company or employer, which may be due to economic conditions of a specific employer or in society as a whole. These furloughs may be ...

ed at the end of the Philadelphia campaign, Scott returned to active service in March 1779 and was ordered to South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

to assist General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

in the southern theater. He arrived in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, just as Henry Clinton had begun his siege of the city. Scott was taken as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

when Charleston surrendered. Paroled in March 1781 and exchanged for Lord Rawdon in July 1782, Scott managed to complete a few recruiting assignments before the war ended.

After the war, Scott visited the western frontier in 1785 and began to make preparations for a permanent relocation. He resettled near present-day Versailles, Kentucky

Versailles () is a home rule-class city in Woodford County, Kentucky, United States. It lies by road west of Lexington and is part of the Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area. Versailles has a population of 9,316 according to 2017 cen ...

, in 1787. Confronted by the dangers of Indian raids, Scott raised a company of volunteers in 1790 and joined Josiah Harmar for an expedition against the Indians. After Harmar's Defeat, President Washington ordered Arthur St. Clair

Arthur St. Clair ( – August 31, 1818) was a Scottish-American soldier and politician. Born in Thurso, Scotland, he served in the British Army during the French and Indian War before settling in Pennsylvania, where he held local office. During ...

to prepare for an invasion of Indian lands in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. In the meantime, Scott, by now holding the rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

in the Virginia militia, was ordered to conduct a series of preliminary raids. In July 1791, he led the most notable and successful of these raids against the village of Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

. St. Clair's main invasion, conducted later that year, was a failure. Shortly after the separation of Kentucky from Virginia in 1792, the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

commissioned Scott as a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and gave him command of the 2nd Division of the Kentucky militia. Scott's division cooperated with "Mad" Anthony Wayne's Legion of the United States for the rest of the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

, including their decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

Having previously served in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

and as a presidential elector

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia app ...

, the aging Scott now ran for governor. His 1808 campaign was skillfully managed by his step-son-in-law, Jesse Bledsoe

Jesse Bledsoe (April 6, 1776June 25, 1836) was a slave owner and Senator from Kentucky.

Life and career

Bledsoe was born in Culpeper County, Virginia in 1776. When he was very young, his family migrated with a Baptist congregation through Cumbe ...

, and he won a convincing victory over John Allen and Green Clay. A fall on the icy steps of the governor's mansion early in his term confined Scott to crutches for the rest of his life, and left him heavily reliant on Bledsoe, whom he appointed Secretary of State. Although he frequently clashed with the state legislature over domestic matters, the primary concern of his administration was the increasing tension between the United States and Great Britain that eventually led to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

. Scott's decision to appoint William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

as brevet major general in the Kentucky militia, although probably in violation of the state constitution as Harrison was not a resident of the state, was nonetheless praised by the state's citizens. After his term expired, Scott returned to his Canewood estate. His health declined rapidly, and he died on October 22, 1813. Scott County, Kentucky, and Scott County, Indiana

Scott County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2010, the population was 24,181. The county seat is Scottsburg.

History

Scott County was formed in 1820 from portions of Clark, Jackson, Jefferson, Jennings, and Washingto ...

, are named in his honor, as is the city of Scottsville, Kentucky

Scottsville is a home rule-class city in Allen County, Kentucky, in the United States. It is the seat of its county. The population was 4,226 during the 2010 U.S. Census.

History

The site along Bays Fork was settled in 1797 and developed into ...

.

Early life and family

Charles Scott was born in 1739, probably in April, in the part ofGoochland County, Virginia

Goochland County is a county located in the Piedmont of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Its southern border is formed by the James River. As of the 2020 census, the population was 24,727. Its county seat is Goochland.

Goochland County is includ ...

, that is now Powhatan County

Powhatan County () is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 30,033. Its county seat is Powhatan.

Powhatan County is included in the Greater Richmond Region.

The James River forms the cou ...

.Harrison, p. 803"Charles Scott". ''Dictionary of American Biography'' His father, Samuel Scott, was a farmer and member of the Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

.Ward (2004), p. 16 His mother, whose name is not known, died most likely around 1745.Ward (1988), p. 2 Scott had an older brother, John, and three younger siblings, Edward, Joseph, and Martha. He received only a basic education from his parents and in the rural Virginia schools near his home.

Shortly after his father died in 1755, Scott was apprenticed to a carpenter.Ward (1988), p. 3 In late July 1755, a local court was preparing to place him with a guardian, but in October, before the court acted, Scott enlisted in the Virginia Regiment. He was assigned to David Bell's company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared ...

. During the early part of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, he won praise from his superiors as a frontier scout and woodsman. Most of his fellow soldiers were undisciplined and poorly trained, allowing Scott to stand out and quickly rise to the rank of corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

.Ward (1988), p. 4 By June 1756, he had been promoted to sergeant

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other ...

.

Many biographies state that Scott served under George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

in the Braddock Expedition, a failed attempt to capture Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

from the French. This, however, is unlikely. There is no record of his claiming participation and his enlistment in the Virginia Regiment occurred after the date of the battle. For most of 1756 and the early part of 1757, he divided his time between Fort Cumberland

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

and Fort Washington, conducting scouting and escort missions.Ward (1988), p. 5 In April 1757, David Bell was relieved of his command as part of a general downsizing of Washington's regiment, and Scott was assigned to Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Robert McKenzie at Fort Pearsall. In August and September, Washington sent Scott and a small scouting party on two reconnaissance missions to Fort Duquesne in preparation for an assault on that fort, but the party learned little on either mission.Ward (1988), p. 6 In November, Scott was part of the Forbes Expedition

The Forbes Expedition was a British military expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, led by Brigadier-General John Forbes in 1758, during the French and Indian War. While advancing to the fort, the expedition built the now historic trail, the Forbes ...

that captured the fort. He spent the latter part of the year at Fort Loudoun, where Washington promoted him to ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

.

Scott spent most of 1759 conducting escort missions and constructing roads and forts.Ward (1988), p. 7 During this time, Virginia's forces were taken from George Washington and put under the control of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

. In July 1760, Scott was named the fifth captain of a group of Virginia troops that Byrd led on an expedition against the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

in 1760. Scott's exact role in the campaign is not known. The expedition was a success, and Virginia Governor Francis Fauquier ordered the force disbanded in February 1762; Scott had left the army at some unknown date prior to that.Ward (1988), p. 8

Sometime prior to 1762, Scott's older brother, John, died, leaving Scott to inherit his father's land near the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

and Muddy Creek. Having left the army, he had settled on his inherited farm by late 1761. On February 25, 1762, he married Frances Sweeney from Cumberland County, Virginia. With the help of approximately 10 slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, Scott engaged in growing tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and milling flour on his farm. In July 1766, he was named one of two captains in the local militia.Ward (1988), p. 9 Over the next several years, Scott and his wife had four boys and four or five girls.

Revolutionary War

As theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

intensified in 1775, Scott raised a company of volunteers in Cumberland County. It was the first company formed south of the James River to participate in the Revolution. The company stood ready to aid Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first a ...

in an anticipated clash with Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

History

The title was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, second son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. He was made Lord Murray of Blair, Moulin and Tillimet (or Tullimet) and V ...

at Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is ...

, in May 1775, but Dunmore abandoned the city in June, and they joined units from the surrounding counties in Williamsburg later that month.Ward (1988), p. 10 In July, the Virginia Convention created two regiments of Virginia troops, one under Patrick Henry and the other under William Woodford.Ward (1988), p. 12 As those leaders departed for Williamsburg, the Conventions acknowledged Scott as temporary commander-in-chief of the volunteers already assembled there. On August 17, 1775, he was elected lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

of Woodford's regiment, the 2nd Virginia. His younger brother, Joseph, served as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the regiment. In December, Woodford dispatched Scott and 150 men to Great Bridge, Virginia

Great Bridge is a community located in the independent city of Chesapeake in the U.S. state of Virginia. Its name is derived from the American Revolutionary War Battle of Great Bridge, which took place on December 9, 1775, and resulted in the fi ...

, to defend a crossing point on the Elizabeth River.Ward (1988), p. 14 Days later, this force played a significant role in the December 9, 1775, Battle of Great Bridge by killing British Captain Charles Fordyce, thereby halting the British advance on the crossing.Ward (1988), p. 15 Following the battle, colonial forces were able to occupy the city of Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia B ...

, and Lord Dunmore eventually departed from Virginia.Ward (1988), p. 17

On February 13, 1776, the 2nd Virginia became a part of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

; Scott retained his rank of lieutenant colonel during the transition.Ward (1988), p. 19 After spending the winter with part of the 2nd Virginia in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

, Scott was chosen by the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

as colonel of the 5th Virginia Regiment on August 12, 1776; he replaced Colonel William Peachy, who had resigned.Ward (1988), p. 20 The 5th Virginia was stationed in the cities of Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

* Hampton, Victoria

Canada

* Hampton, New Brunswick

*Ha ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

through the end of September. They were then ordered to join George Washington in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

, eventually repairing to the city of Trenton in November.

Serving as part of Adam Stephen's brigade, Scott's 5th Virginia Regiment fought in the colonial victory at the December 26 Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton was a small but pivotal American Revolutionary War battle on the morning of December 26, 1776, in Trenton, New Jersey. After General George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River north of Trenton the previous night, ...

.Ward (2004), p. 17 During the subsequent Battle of the Assunpink Creek

The Battle of the Assunpink Creek, also known as the Second Battle of Trenton, was a battle between American and British troops that took place in and around Trenton, New Jersey, on January 2, 1777, during the American Revolutionary War, an ...

on January 2, 1777, the 5th Virginia helped slow the advance of a combined force of British light infantry and Hessian mercenaries toward Trenton. Major George Johnston, a member of the 5th Virginia, opined that Scott had "acquired immortal honor" from his performance at Assunpink Creek.Ward (1988), p. 26 Following these battles, Washington's main force prepared to spend the winter at Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Chatham.Ward (1988), p. 28 From this base, he led light infantry raids against British foraging parties. In his most notable engagement – the February 1 Battle of Drake's Farm – he performed well against a superior combination of British and Hessian soldiers.Fredriksen, p. 623 He led another notable raid against a large British force of about 2,000 at the February 8

In March 1777, Scott returned to his Virginia farm, taking his first

In March 1777, Scott returned to his Virginia farm, taking his first

Soon after Washington's orders were delivered, a British raiding party under George Collier and Edward Mathew arrived in Virginia to capture or destroy supplies that might otherwise be sent southward to aid the reinforcements going to South Carolina.Ward (1988), p. 70 Scott's orders changed again; the

Soon after Washington's orders were delivered, a British raiding party under George Collier and Edward Mathew arrived in Virginia to capture or destroy supplies that might otherwise be sent southward to aid the reinforcements going to South Carolina.Ward (1988), p. 70 Scott's orders changed again; the

In October 1783, the Virginia Legislature authorized Scott to commission superintendents and surveyors to survey the lands given to soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War. Enticed by glowing reports of Kentucky by his friend,

In October 1783, the Virginia Legislature authorized Scott to commission superintendents and surveyors to survey the lands given to soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War. Enticed by glowing reports of Kentucky by his friend,

As tensions mounted between the Indians in the

As tensions mounted between the Indians in the

In July, Scott gave permission to Bourbon County resident

In July, Scott gave permission to Bourbon County resident

Wayne originally intended to use Kentucky militiamen in preemptive strikes against the Indians and to conduct the main invasion using only federal troops, but by the time he moved to Fort Washington in mid-1793, he had assembled fewer than 3,000 of the 5,000 troops he had anticipated.Nelson, p. 239 He now requested that Scott's and Logan's men join his main force.Nelson, p. 240 Logan flatly refused to cooperate with a federal officer, but Scott eventually agreed, and Wayne commissioned him an officer in the federal army on July 1, 1793. He and Governor Isaac Shelby instituted a draft to raise the 1,500 troops he was to command in Wayne's operation.Ward (1988), p. 130 When he joined Wayne at Fort Jefferson on October 21, 1793, he had only been able to raise 1,000 men.Nelson, p. 241Ward (1988), p. 131

On November 4, Wayne ordered Scott's militiamen to destroy a nearby Delaware village.Nelson, p. 242 Still resentful and distrustful of federal officers and aware that Wayne would not launch a major offensive so close to winter, the men were not enthusiastic about the mission, which many of them considered trivial.Ward (1988), p. 134 That night, 501 of them deserted their camp, though Wayne noted in his report that he believed Scott and his officers had done all they could do to prevent the desertions. Scott attempted to continue the mission with his remaining men, but inclement weather prevented him from conducting a major offensive. Ultimately, the men were only able to disperse a small hunting camp before continuing on to Fort Washington and mustering out on November 10. Wayne ordered Scott to return with a full quota of troops after the winter.

Tensions cooled between Wayne and the Kentuckians over the winter of 1793–94.Nelson, p. 243 Wayne noticed that, despite their obstinance, the Kentucky volunteers appeared to be good soldiers. The militiamen, after observing Wayne, concluded that he – unlike Harmar and St. Clair – knew how to combat the Indians. Wayne augmented his popularity in Kentucky by building Fort Recovery over the winter on the site of St. Clair's defeat.Ward (1988), p. 136 The Indians' victory over St. Clair had become a part of their lore and inspired them to continue the fight against the western settlers; Wayne's construction of a fort on this site was a blow to the Indian psyche, and his re-burial of some 600 skulls that the Indians had dug up and scattered across the area was popular with Kentuckians, since many of their own were among the dead. While Scott came to respect Wayne personally, his friend, James Wilkinson, began an anonymous campaign to tarnish Wayne's image, coveting command of the Northwest expedition for himself.Nelson, p. 244 Scott, on leave in Philadelphia at the time, wrote to

Wayne originally intended to use Kentucky militiamen in preemptive strikes against the Indians and to conduct the main invasion using only federal troops, but by the time he moved to Fort Washington in mid-1793, he had assembled fewer than 3,000 of the 5,000 troops he had anticipated.Nelson, p. 239 He now requested that Scott's and Logan's men join his main force.Nelson, p. 240 Logan flatly refused to cooperate with a federal officer, but Scott eventually agreed, and Wayne commissioned him an officer in the federal army on July 1, 1793. He and Governor Isaac Shelby instituted a draft to raise the 1,500 troops he was to command in Wayne's operation.Ward (1988), p. 130 When he joined Wayne at Fort Jefferson on October 21, 1793, he had only been able to raise 1,000 men.Nelson, p. 241Ward (1988), p. 131

On November 4, Wayne ordered Scott's militiamen to destroy a nearby Delaware village.Nelson, p. 242 Still resentful and distrustful of federal officers and aware that Wayne would not launch a major offensive so close to winter, the men were not enthusiastic about the mission, which many of them considered trivial.Ward (1988), p. 134 That night, 501 of them deserted their camp, though Wayne noted in his report that he believed Scott and his officers had done all they could do to prevent the desertions. Scott attempted to continue the mission with his remaining men, but inclement weather prevented him from conducting a major offensive. Ultimately, the men were only able to disperse a small hunting camp before continuing on to Fort Washington and mustering out on November 10. Wayne ordered Scott to return with a full quota of troops after the winter.

Tensions cooled between Wayne and the Kentuckians over the winter of 1793–94.Nelson, p. 243 Wayne noticed that, despite their obstinance, the Kentucky volunteers appeared to be good soldiers. The militiamen, after observing Wayne, concluded that he – unlike Harmar and St. Clair – knew how to combat the Indians. Wayne augmented his popularity in Kentucky by building Fort Recovery over the winter on the site of St. Clair's defeat.Ward (1988), p. 136 The Indians' victory over St. Clair had become a part of their lore and inspired them to continue the fight against the western settlers; Wayne's construction of a fort on this site was a blow to the Indian psyche, and his re-burial of some 600 skulls that the Indians had dug up and scattered across the area was popular with Kentuckians, since many of their own were among the dead. While Scott came to respect Wayne personally, his friend, James Wilkinson, began an anonymous campaign to tarnish Wayne's image, coveting command of the Northwest expedition for himself.Nelson, p. 244 Scott, on leave in Philadelphia at the time, wrote to

As the celebrations in honor of Scott's military career continued across Kentucky, he began to consider the possibility of running for governor in 1808.Ward (1988), p. 158 By mid-1806, state senator Thomas Posey and Lexington lawyer Thomas Todd had already declared their candidacies. Posey had been chosen speaker pro tem of the state Senate and, with the death of

As the celebrations in honor of Scott's military career continued across Kentucky, he began to consider the possibility of running for governor in 1808.Ward (1988), p. 158 By mid-1806, state senator Thomas Posey and Lexington lawyer Thomas Todd had already declared their candidacies. Posey had been chosen speaker pro tem of the state Senate and, with the death of

Among Scott's first acts as governor was appointing Jesse Bledsoe as Secretary of State.Ward (1988), p. 170 Bledsoe delivered Scott's first address to the legislature on December 13, 1808.Ward (1988), p. 171 Later that winter, Scott was injured when he slipped on the icy steps of the governor's mansion; the injury left him confined to crutches for the rest of his life and rendered him even more dependent on Bledsoe to perform many of his official functions.Ward (2004), p. 18 His physical condition continued to worsen throughout his term as governor.Ward (1988), p. 182

In domestic matters, Scott advocated increased salaries for public officials, economic development measures, and heavy punishments for persistent criminals. While he desired a tax code that would preclude the need for the state to borrow money, he encouraged legislators to keep taxes as low as possible. He also urged them to convert the militia into a youth army. The General Assembly routinely ignored his calls for reform but did pass a measure he advocated that allowed debtors a one-year stay on collection of their debts if they provided both

Among Scott's first acts as governor was appointing Jesse Bledsoe as Secretary of State.Ward (1988), p. 170 Bledsoe delivered Scott's first address to the legislature on December 13, 1808.Ward (1988), p. 171 Later that winter, Scott was injured when he slipped on the icy steps of the governor's mansion; the injury left him confined to crutches for the rest of his life and rendered him even more dependent on Bledsoe to perform many of his official functions.Ward (2004), p. 18 His physical condition continued to worsen throughout his term as governor.Ward (1988), p. 182

In domestic matters, Scott advocated increased salaries for public officials, economic development measures, and heavy punishments for persistent criminals. While he desired a tax code that would preclude the need for the state to borrow money, he encouraged legislators to keep taxes as low as possible. He also urged them to convert the militia into a youth army. The General Assembly routinely ignored his calls for reform but did pass a measure he advocated that allowed debtors a one-year stay on collection of their debts if they provided both  In September 1811,

In September 1811,

The Battle of Drake's Farm

8thVirginia.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Charles 1739 births 1813 deaths American militia generals American slave owners American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by Great Britain British America army officers Burials at Frankfort Cemetery Continental Army generals American people of the Northwest Indian War Governors of Kentucky Kentucky Democratic-Republicans Members of the Virginia House of Delegates People of Virginia in the American Revolution People of Virginia in the French and Indian War People from Powhatan County, Virginia People from Kentucky in the War of 1812 1792 United States presidential electors 1800 United States presidential electors 1804 United States presidential electors People from Versailles, Kentucky Virginia colonial people Democratic-Republican Party state governors of the United States 19th-century American politicians

Battle of Quibbletown

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

.

Philadelphia campaign

In March 1777, Scott returned to his Virginia farm, taking his first

In March 1777, Scott returned to his Virginia farm, taking his first furlough

A furlough (; from nl, verlof, " leave of absence") is a temporary leave of employees due to special needs of a company or employer, which may be due to economic conditions of a specific employer or in society as a whole. These furloughs may be ...

in more than a year.Ward (1988), p. 31 In recognition of his service with Washington, Congress commissioned him a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

on April 2, 1777.Trowbridge, "Kentucky's Military Governors" At Washington's request, he returned to Trenton on May 10, 1777. His 4th Virginia Brigade and another brigade under William Woodford constituted the Virginia division, commanded by Adam Stephen, who had been promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

. With Stephen and Brigadier General William Maxwell ill, Scott assumed temporary command of the division between May 19 and 24.Ward (1988), p. 32 Washington spent much of mid-1777 trying to anticipate and counter the moves of British General William Howe, and the lull in the fighting allowed Scott time to file a protest with Congress regarding how his seniority and rank had been calculated. After eight months of deliberation, Congress concurred with Scott's protest, placing him ahead of fellow brigadier general George Weedon

George Weedon (1734–1793) was an American soldier during the Revolutionary War from Fredericksburg, Colony of Virginia. He served as a brigadier general in the Continental Army and later in the Virginia militia. After the Revolutionary War e ...

in seniority.Ward (1988), p. 34

At the September 11 Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, Sir William Howe on September& ...

, the 4th Virginia Brigade stubbornly resisted the advance of General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

, but was ultimately forced to retreat. Following the British victory, Howe marched toward Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, stopping briefly at Germantown Germantown or German Town may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Germantown, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

United States

* Germantown, California, the former name of Artois, a census-designated place in Glenn County

* G ...

.Ward (1988), p. 37 Scott persistently advocated for an attack on Howe's position at Germantown, and although he was initially in the minority among Washington's generals, he ultimately prevailed upon Washington to conduct the attack.Ward (1988), p. 39 On October 4, 1777, the 4th Virginia attacked the British in the Battle of Germantown

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Con ...

.Fredriksen, p. 624 Because of their circuitous route to the battle, the field was already covered by heavy smoke from musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s and a fire set by the British in a dry buckwheat

Buckwheat (''Fagopyrum esculentum''), or common buckwheat, is a flowering plant in the knotweed family Polygonaceae cultivated for its grain-like seeds and as a cover crop. The name "buckwheat" is used for several other species, such as ''Fagop ...

field when they arrived; they and the other colonial forces were lost in the smoke and retreated.

After the defeat at Germantown, Washington's troops took a position in the hills surrounding Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania, about from Philadelphia.Ward (1988), p. 40 Scott and four other generals initially favored an attack on Philadelphia in December, but after hearing Washington's assessment of the enemy's defenses there, they abandoned the idea. After a series of skirmishes with Howe's men near Whitemarsh, Washington's army camped for the winter at Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the ...

. Scott was afforded the luxury of boarding at the farm of Samuel Jones, about three miles from the camp, but rode out to inspect his brigade daily. Washington granted him a furlough in mid-March 1778, and he returned to Valley Forge on May 20, 1778.Ward (1988), p. 46

When Washington and his men abandoned Valley Forge in mid-June 1778, Scott was ordered to take 1,500 light infantrymen and harass the British forces as they marched across New Jersey.Ward (1988), p. 48 On June 26, the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

joined Scott with an additional 1,000 men, in anticipation of a major offensive the next day. General Charles Lee was chosen to command the operation, which was delayed by one day due to inadequate communications and delays in forwarding provisions. Lee shared no battle plan with his generals, later claiming he had insufficient intelligence to form one.Ward (1988), p. 49 On the morning of June 28, Lee launched the attack, beginning the Battle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Court House, was fought near Monmouth Court House in modern-day Freehold Borough, New Jersey on June 28, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It pitted the Continental Army, co ...

. During the battle, Scott observed American artillerymen retreating. Not realizing that the men had only run out of ammunition, Scott believed the retreat was a sign of the collapse of the American offensive and ordered his men to retreat as well. Lacking a battle plan for guidance, William Maxwell and Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

, whose units were fighting adjacent to Scott's men, also ordered a retreat. With such a great number of his men retreating, Lee fell back and eventually aborted the offensive. Although Washington's main force arrived and stopped the British advance, Scott's retreat was partially blamed for giving them control of the battle.Ward (1988), p. 51 Tradition holds that, in the aftermath of the battle, Scott witnessed Washington excoriating Lee in a profanity-laden tirade, but biographer Harry M. Ward considered it unlikely that Scott was present at the meeting. Lee was later court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed for the retreat and suspended from command.Ward (1988), p. 52

Following the Battle of Monmouth, the British retreated to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. On August 14, Scott was given command of a new light infantry corps organized by Washington.Ward (1988), p. 53 He also served as Washington's chief of intelligence, conducting constant scouting missions from the Americans' new base at White Plains, New York

(Always Faithful)

, image_seal = WhitePlainsSeal.png

, seal_link =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = State

, subdivision_name1 =

, subdivis ...

. While Scott's men engaged in a few skirmishes with British scouting parties, neither Washington's army nor the British force at New York City conducted any major operations before Scott was furloughed in November 1778.

Service in the southern theater and capture

A March 1779 letter from Washington to Scott, still on furlough in Virginia, ordered him to recruit volunteers in Virginia and join Washington at Middlebrook on May 1.Ward (1988), p. 68 Men and supplies proved difficult to obtain, delaying Scott's return; during the delay, Washington ordered the recruits toSouth Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

to join Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

, who was in command of the militia forces there.Ward (1988), p. 69 Reports of significant British troop movements toward Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

had convinced Washington that the enemy was preparing an invasion from the south.

Soon after Washington's orders were delivered, a British raiding party under George Collier and Edward Mathew arrived in Virginia to capture or destroy supplies that might otherwise be sent southward to aid the reinforcements going to South Carolina.Ward (1988), p. 70 Scott's orders changed again; the

Soon after Washington's orders were delivered, a British raiding party under George Collier and Edward Mathew arrived in Virginia to capture or destroy supplies that might otherwise be sent southward to aid the reinforcements going to South Carolina.Ward (1988), p. 70 Scott's orders changed again; the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

ordered him to immediately prepare defenses against Collier and Mathew's raids. When it became clear to both the legislature and Washington that Collier and Mathew intended only to raid supplies, not to invade, they concluded that the local militia would be able to sufficiently protect Virginia's interests and that Scott should continue to recruit men to reinforce the south.Ward (1988), p. 71 The legislators presented him with a horse, a firearm, and 500 pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

for his quick response to the threat.

Scott's recruiting difficulties in Virginia continued, despite the implementation of a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

by the state legislature.Ward (1988), p. 72 Finally, in October 1779, he forwarded troops sent to him from Washington's Northern Army on to Lincoln in South Carolina, fulfilling his quota.Ward (1988), p. 73 He retained only Abraham Buford's regiment with him in Virginia. In February 1780, about 750 men sent by Washington under William Woodford arrived at Scott's camp in Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Econ ...

.Ward (1988), p. 74 Virginia authorities, fearing that the British force to the south under General Henry Clinton would turn north to Virginia, detained Scott and Woodford until it was clear that Clinton's object was Lincoln's position at Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

.

On March 30, 1780, Scott arrived in Charleston just as Clinton was laying siege to the city. He was captured when the city surrendered on May 12, 1780, and was held as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

at Haddrell's Point near Charleston. Although he was a prisoner, he was given freedom to move within a six-mile radius and was allowed to correspond and trade with acquaintances in Virginia. With the death of William Woodford on November 13, 1780, he became primarily responsible for the welfare of the Virginia troops at Haddrell's Point.Ward (1988), p. 78 He requested his parole on account of ill health on January 30, 1781, and in late March, Charles Cornwallis granted the request.Ward (1988), p. 81

In July 1782, Scott was exchanged for Lord Rawdon, ending his parole. Washington informed him that he was back on active duty and ordered him to assist General Peter Muhlenberg

John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg (October 1, 1746October 1, 1807) was an American clergyman, Continental Army soldier during the American Revolutionary War, and political figure in the newly independent United States. A Lutheran minister, he serve ...

's recruiting efforts in Virginia, then to report to General Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

.Ward (1988), p. 83 Greene wrote that he did not have a command for Scott, and requested that he remain with Muhlenberg in Virginia. The few troops he was able to recruit were sent to a depot at Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is the most north western independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Frederick County, although the two are separate jurisdictions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Winchester wit ...

.Ward (1988), p. 86 When the preliminary articles of peace between the United States and Great Britain were signed in March 1783, recruiting stopped altogether. Scott was brevetted to major general on September 30, 1783, just prior to his discharge from the Continental Army. Following the war, he became one of the founding members of the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

.

Settlement in Kentucky and early political career

In October 1783, the Virginia Legislature authorized Scott to commission superintendents and surveyors to survey the lands given to soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War. Enticed by glowing reports of Kentucky by his friend,

In October 1783, the Virginia Legislature authorized Scott to commission superintendents and surveyors to survey the lands given to soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War. Enticed by glowing reports of Kentucky by his friend, James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, bu ...

, he arranged for a cabin to be built for him near the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. The river and its t ...

, although the builder apparently laid only the cornerstone.Ward (1988), p. 90 Scott first visited Kentucky in mid-1785.Ward (1988), p. 91 Traveling with Peyton Short, one of Wilkinson's business partners, he came to Limestone (present-day Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a home rule-class city in Mason County, Kentucky, United States and is the seat of Mason County. The population was 8,782 as of 2019, making it the 51st-largest city in Kentucky by population. Maysville is on the Ohio River, north ...

) via the Monongahela and Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

Rivers. Scott and Short then traveled overland to the Kentucky River to examine the land they would later claim. Scott's stay in Kentucky was a short one; he had returned to his farm in Virginia by September 1785.

On his return to Virginia, Scott employed Edward Carrington, former quartermaster general of the Southern Army, to set his financial affairs in order in preparation for a move to Kentucky. Carrington purchased Scott's Virginia farm in 1785, but allowed the family to live there until they moved to the frontier.Ward (1988), p. 92 In 1787, Scott settled near the city of Versailles, Kentucky

Versailles () is a home rule-class city in Woodford County, Kentucky, United States. It lies by road west of Lexington and is part of the Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area. Versailles has a population of 9,316 according to 2017 cen ...

. Between his military claims and those of his children, the Scott family was entitled to in Fayette and Bourbon counties.Clark and Lane, p. 13 Scott constructed a two-story log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

, a stockade, and a tobacco inspection warehouse. In June 1787, Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

warriors killed and scalped

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

his son, Samuel, while he was crossing the Ohio River in a canoe; the elder Scott watched helplessly from the riverbank.Ward (1988), p. 96 Although a small party of settlers pursued the Shawnees back across the river, they were not able to overtake them.Ward (1988), p. 97 In volume three of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's ''The Winning of the West'', he stated that Scott "delighted in war" against the Indians after the death of his son.Nelson, p. 220

Scott focused on the development of his homestead as a way to deal with the grief of losing his son. The settlement became known as Scott's Landing, and Scott briefly served as a tobacco inspector for the area. Determined to make Scott's Landing the centerpiece of a larger settlement called Petersburg, he began selling lots near the settlement in November 1788.Ward (1988), p. 98 Among those who purchased lots were James Wilkinson, Abraham Buford, Judge George Muter, and future Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

and Kentucky Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re- ...

Christopher Greenup

Christopher Greenup (c. 1750 – April 27, 1818) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative and the third Governor of Kentucky. Little is known about his early life; the first reliable records about him are documents recordi ...

.

Scott was one of 37 men who founded the Kentucky Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge in 1787.Ward (1988), p. 99 Although he did not participate in any of the ten statehood conventions that sought to separate Kentucky from Virginia, he supported the idea in principle.Ward (1988), p. 100 When Woodford County was formed from the part of Fayette County that included Scott's fledgling settlement, Scott declined appointment as the new county's lieutenant.Ward (1988), p. 101 He consented to be a candidate to represent the county in the Virginia House of Delegates. During his single term, he served on the committee on privileges and election and on several special committees, including one that recommended that President George Washington supply a military guard at Big Bone Lick to facilitate the establishment of a saltworks there.

Northwest Indian War

As tensions mounted between the Indians in the

As tensions mounted between the Indians in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

and settlers on the Kentucky frontier, President Washington began sanctioning joint operations between federal army troops and local frontier militia against the Indians.Nelson, p. 223 In April 1790, Scott raised a contingent of volunteers from Bourbon and Fayette counties to join Josiah Harmar in a raid against the Western Confederacy along the Scioto River

The Scioto River ( ) is a river in central and southern Ohio more than in length. It rises in Hardin County just north of Roundhead, Ohio, flows through Columbus, Ohio, where it collects its largest tributary, the Olentangy River, and meets t ...

in what would become the U.S. state of Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

.Nelson, p. 224 The combined force of regulars and militia departed from Limestone on April 18, 1790, crossing the Ohio River and marching to the upper Scioto. From there, they headed south, toward the present-day city of Portsmouth, Ohio

Portsmouth is a city in and the county seat of Scioto County, Ohio, United States. Located in southern Ohio south of Chillicothe, it lies on the north bank of the Ohio River, across from Kentucky, just east of the mouth of the Scioto River. ...

, and discovered an abandoned Indian camp.Ward (1988), p. 102 Fresh footprints, including those of a well-known Shawnee warrior – nicknamed Reel Foot because of his two club feet

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Club (magazine), ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a ''Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands a ...

– led away from the camp site. Scott sent a small detachment to follow the tracks; ultimately, they discovered, killed, and scalped four Shawnees, including Reel Foot. Other than this, the expedition accomplished nothing, and it disbanded on April 27, 1790.

In June 1790, Harmar and Arthur St. Clair

Arthur St. Clair ( – August 31, 1818) was a Scottish-American soldier and politician. Born in Thurso, Scotland, he served in the British Army during the French and Indian War before settling in Pennsylvania, where he held local office. During ...

were ordered to lead another expedition against the Indians.Ward (1988), p. 103 Harmar had hoped that Scott, Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina. He was also a soldier in Lord Dunmore's War, the American Revolutionary Wa ...

, or Benjamin Logan would join the campaign and lead the Kentucky militia, but all three declined. Scott had been elected to represent Woodford County in the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 16 ...

, and his legislative duty prevented his service. He believed that the Kentucky militiamen would only serve under Colonel Robert Trotter, a veteran of Logan's earlier Indian fighting campaigns. Ultimately, command of the Kentucky militiamen was given to Major John Hardin, and many militiamen refused to join the campaign, just as Scott had predicted. During the expedition, Scott's son, Merritt, who was serving as a captain in the Woodford County militia, was killed and scalped. The entire expedition was a failure, and it solidified the Kentucky militiamen's strong distrust of Harmar; most vowed never to fight alongside him again.

During Harmar's Campaign, Scott was serving in the state legislature in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

.Ward (1988), p. 104 He was once again appointed to the committee on privileges and election. He also served on the committee on propositions and grievances and several special committees. On December 30, 1790, Virginia Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes the ...

Beverley Randolph, possibly acting on a recommendation from Washington, appointed Scott brigadier general in the Virginia militia and gave him command of the entire District of Kentucky.Nelson, p. 227 His primary responsibility was overseeing a line of 18 outposts along the Ohio River.Ward (1988), p. 108 In January 1791, President Washington accepted U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

John Brown's suggestion to appoint a Kentucky Board of War, composed of Brown, Scott, Isaac Shelby, Harry Innes, and Benjamin Logan.Harrison and Klotter, p. 70 The committee was empowered to call out local militia to act in conjunction with federal troops against the Indians.Ward (1988), p. 107 They recommended assembling an army of volunteers to locate and destroy Indian settlements north of the Ohio River. Later that month, Washington approved a plan to invade the Indians' homelands via a raid from Fort Washington (near present-day Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

).Nelson, p. 228 Most Kentuckians were displeased with Washington's choice of Arthur St. Clair, by then suffering from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

and unable to mount his own horse unassisted, as overall commander of the invasion. Scott was chosen to serve under St. Clair as commander of the 1,000 militiamen who took part in the invasion, about one-third of the total force.

The Blackberry Campaign

Washington ordered Scott to conduct a series of preliminary raids in mid-1791 that would keep the enemy occupied while St. Clair assembled the primary invasion force.Nelson, p. 229 Both Isaac Shelby and Benjamin Logan had hoped to lead the campaign, and neither would accept a lesser position.Ward (1988), p. 109 Shelby nevertheless supported the campaign, while Logan actively opposed it. Scott issued a call for volunteers to assemble atFrankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, United States, and the seat of Franklin County. It is a home rule-class city; the population was 28,602 at the 2020 census. Located along the Kentucky River, Frankfort is the pr ...

, on May 15, 1791, to carry out these raids. Kentuckians responded favorably to the idea of an all-militia campaign, and 852 men volunteered for service, although Scott was only authorized to take 750; Senator John Brown was among the volunteers. After a brief delay to learn the fate of a failed diplomatic mission to the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

tribes in the Northwest Territory, Scott's men departed from Fort Washington on May 24. The militiamen crossed the Ohio toward a clutch of Miami, Kickapoo, Wea, and Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

settlements near the location of present-day Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

.Nelson, p. 230 For eight days, they crossed rugged terrain and were bedraggled by frequent rainstorms. The harsh conditions spoiled the militia's supplies, and they resorted to gathering the blackberries that were growing in the area; for this reason, the expedition earned the nickname the "Blackberry Campaign".

As Scott's men reached an open prairie near the Wea settlement of Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

on June 1, they were discovered by an enemy scout and hurried to attack the villages before the residents could react. When the main force reached the villages, they found the residents hurriedly fleeing across the Wabash River

The Wabash River (French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows from ...

in canoes.Nelson, p. 231 Aided by cover fire from a Kickapoo village on the other side of the river, they were able to escape before Scott's men could attack. The river was too wide to ford at Scott's location, so he sent a detachment under James Wilkinson in one direction and a detachment under Thomas Barbee in the other to find a place to ford the river. Wilkinson did not find a suitable location, but located and killed a small band of Indians before returning. Barbee located a crossing and conducted a brief raid against the Indians on the other side before returning to Scott. The next morning, Scott's main force burned the nearby villages and crops, while a detachment under Wilkinson set out for the settlement of Kethtippecannunk. The inhabitants of this village had fled across Eel Creek, and after a brief and ineffective firefight, Wilkinson's men burned the city and returned to Scott. In his official report, Scott noted that many of Kethtippecannunk's residents were French and speculated that it was connected to, perhaps dependent upon, the French settlement of Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

.Ward (1988), p. 112

Low on supplies, Scott and his men ended their campaign.Nelson, p. 232 On the return trip, two men drowned in the White River; these were the only deaths among Scott's men.Ward (1988), p. 114 Five others were wounded but survived. In total, they had killed 38 Indians and taken 57 more prisoner. Scott sent 12 men ahead with the official report for Arthur St. Clair's review; the rest of the men arrived at Fort Steuben (present-day Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River and is a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 22,333 at the 2020 census. The town was founded in 1783 by early resident George Rogers Cla ...

) on June 15. The next day, they recrossed the Ohio River and received their discharge papers at Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

.Ward (1988), p. 115

St. Clair expedition

Scott's Wabash Campaign was well-received both in Kentucky and by the Washington administration. On June 24, 1791, Arthur St. Clair encouraged the Board of War to organize a second expedition into the Wabash region and to remove their outposts along the Ohio River to free up manpower and finances as a prelude to his larger invasion.Nelson, p. 233 Scott questioned the wisdom of removing the outposts and convinced his fellow members of the Board of War to retain one at Big Bone Lick and one guarding anironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomer ...

at the mouth of the Kentucky River. His instincts later proved to be right; a month later, Indian raiders tried to deny the frontier settlers access to salt by capturing Big Bone Lick, but they were repelled by the militia stationed at the outpost there. Scott also did not believe that 500 men, St. Clair's requested number for the second Wabash expedition, was sufficient for an effective operation.

In July, Scott gave permission to Bourbon County resident

In July, Scott gave permission to Bourbon County resident John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

to lead 300 men against a band of Indians suspected of stealing horses on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Although Edwards' expedition almost reached the Sandusky River

The Sandusky River ( wyn, saandusti; sjw, Potakihiipi ) is a tributary to Lake Erie in north-central Ohio in the United States. It is about longU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Ma ...

, they found only deserted villages.Ward (1988), p. 116 Unknown to the volunteers, they narrowly missed being ambushed by the Indians in the area. Many of the men who accompanied Edwards accused him of cowardice. Due to illness, Scott was unable to lead the expedition St. Clair requested; instead, he chose his friend, James Wilkinson, to lead it. Wilkinson's men departed on August 1. During their expedition, they destroyed the evacuated village of Kikiah (also called Kenapocomoco), the rebuilt settlement of Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

, a small Kickapoo village, and several other small settlements in the area. Returning by the same route that Scott's previous expedition had, Wilkinson's men were back in Kentucky by August 21. Scott's and Wilkinson's campaigns took a heavy toll on the Northwest Indians. In particular, the and Kickapoos signed a peace treaty with the United States the following year, and the Kickapoos migrated farther into Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

.

St. Clair continued his preparations for invading the northwest despite the fact that, by now, he admitted he was unfit for combat due to his ill health.Nelson, p. 234 Like Harmar, he was also unpopular in Kentucky, and Scott had to conduct a draft to raise the militiamen needed for St. Clair's expedition.Harrison and Klotter, p. 71 He and most other officers in Kentucky claimed they were too ill to lead the men; most actually feared losing the respect of Kentuckians through their association with St. Clair. Colonel William Oldham was the highest-ranking soldier willing to lead the Kentuckians.

St. Clair's party left Fort Washington on October 1. On November 3, he ordered his men to make camp on a small tributary of the Wabash River, mistakenly believing they were camping on the St. Marys River. His intent was for the men to construct some protective works the next day, but before sunrise, a combined group of Miami and Canadians