Charles Of Anjou on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou, was a member of the royal

In December 1244 Louis IX took a vow to lead a crusade. Ignoring their mother's strong opposition, his three brothersRobert, Alphonse and Charlesalso took the cross. Preparations for the crusade lasted for years, with the crusaders embarking at

In December 1244 Louis IX took a vow to lead a crusade. Ignoring their mother's strong opposition, his three brothersRobert, Alphonse and Charlesalso took the cross. Preparations for the crusade lasted for years, with the crusaders embarking at

Charles's officials continued to ascertain his rights, visiting each town and holding public enquiries to obtain information about all claims. The count's salt monopoly (or ) was introduced in the whole county. Income from the salt trade made up about 50% of state revenues by the late 1250s. Charles abolished local tolls and promoted shipbuilding and

Charles's officials continued to ascertain his rights, visiting each town and holding public enquiries to obtain information about all claims. The count's salt monopoly (or ) was introduced in the whole county. Income from the salt trade made up about 50% of state revenues by the late 1250s. Charles abolished local tolls and promoted shipbuilding and

Charles decided to invade southern Italy without delay, because he was unable to finance a lengthy campaign. He left Rome on 20January 1266. He marched towards

Charles decided to invade southern Italy without delay, because he was unable to finance a lengthy campaign. He left Rome on 20January 1266. He marched towards

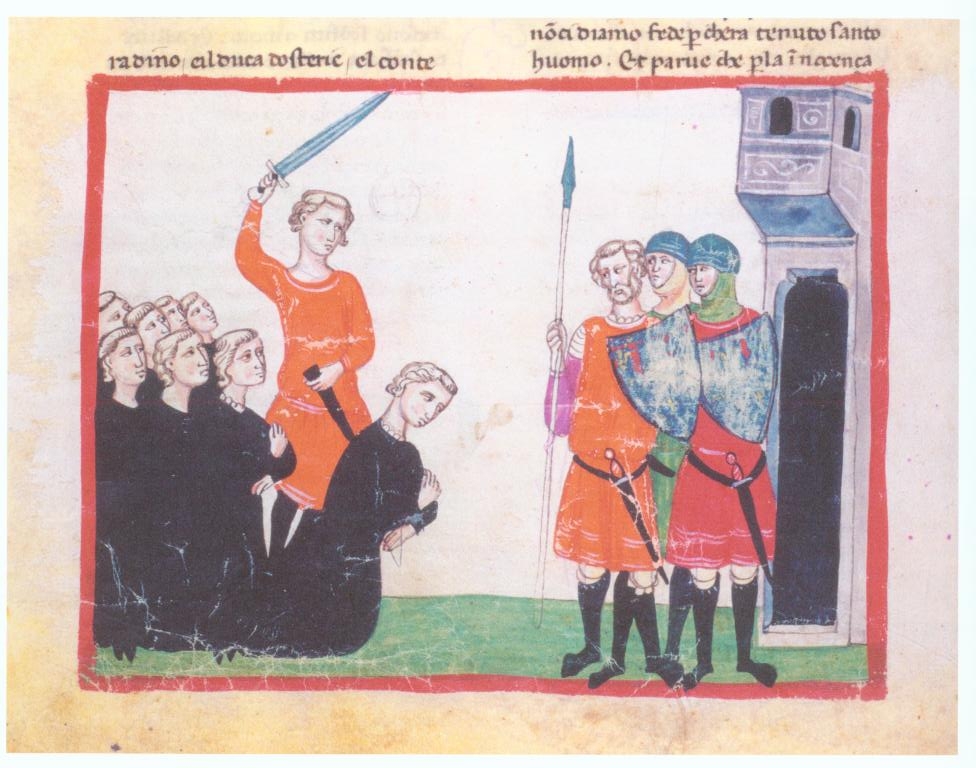

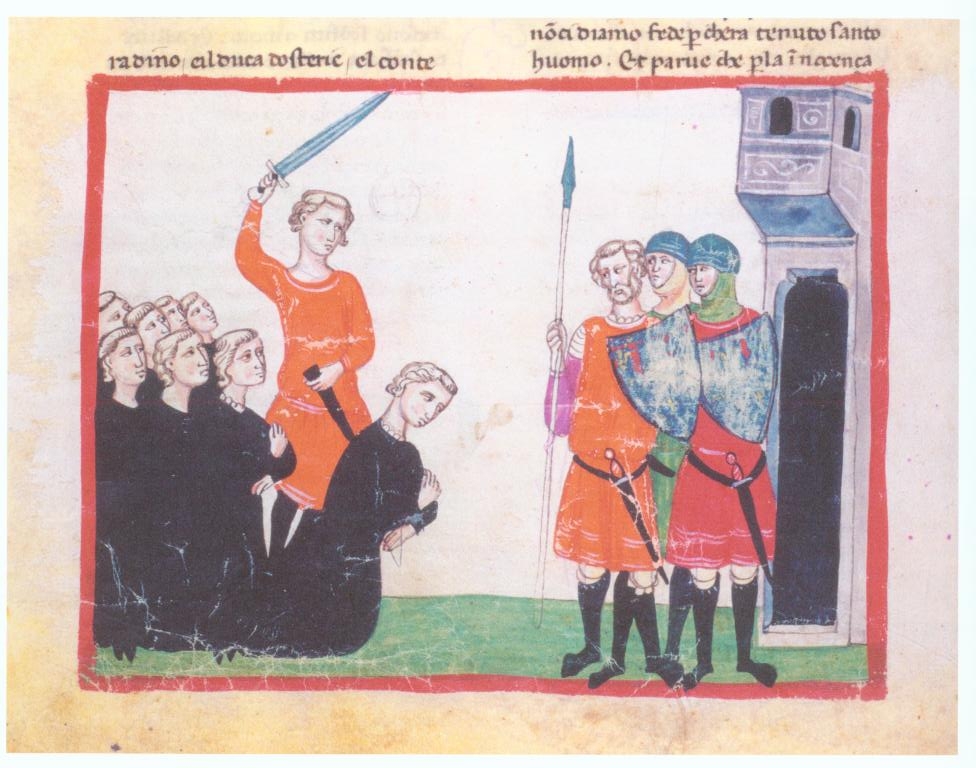

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November. Manfred's staunchest supporters had meanwhile fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade Conrad IV's 15-year-old son

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November. Manfred's staunchest supporters had meanwhile fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade Conrad IV's 15-year-old son

An earthquake destroyed the walls of Durazzo in the late 1260s or early 1270s. Charles's troops took possession of the town with the assistance of the leaders of the nearby Albanian communities. Charles concluded an agreement with the Albanian chiefs, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties in February 1272. He adopted the title of

An earthquake destroyed the walls of Durazzo in the late 1260s or early 1270s. Charles's troops took possession of the town with the assistance of the leaders of the nearby Albanian communities. Charles concluded an agreement with the Albanian chiefs, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties in February 1272. He adopted the title of

Pope Gregory X died on 10January 1276. After the hostility he experienced during Gregory's pontificate, Charles was determined to secure the election of a pope willing to support his plans. Gregory's successor,

Pope Gregory X died on 10January 1276. After the hostility he experienced during Gregory's pontificate, Charles was determined to secure the election of a pope willing to support his plans. Gregory's successor,

Always in need of funds, Charles could not cancel the , although it was the most unpopular tax in the Regno. Instead he granted exemptions to individuals and communities, especially to the French and Provençal colonists, which increased the burden on those who did not enjoy such privileges. The yearly, or occasionally more frequent, obligatory exchange of the the coins almost exclusively used in local transactionswas also an important, and unpopular, source of revenue for the royal treasury. Charles took out forced loans whenever he needed "immediately a large sum of money for certain arduous and pressing business", as he explained in one of his decrees.

Always in need of funds, Charles could not cancel the , although it was the most unpopular tax in the Regno. Instead he granted exemptions to individuals and communities, especially to the French and Provençal colonists, which increased the burden on those who did not enjoy such privileges. The yearly, or occasionally more frequent, obligatory exchange of the the coins almost exclusively used in local transactionswas also an important, and unpopular, source of revenue for the royal treasury. Charles took out forced loans whenever he needed "immediately a large sum of money for certain arduous and pressing business", as he explained in one of his decrees.

Charles went to

Charles went to

All records show that Charles was a faithful husband and a caring father. His first wife, Beatrice of Provence, gave birth to at least six children. According to contemporaneous gossips, she persuaded Charles to claim the Kingdom of Sicily, because she wanted to wear a crown like her sisters. Before she died in July 1267, she had willed the usufruct of Provence to Charles.

* Blanche, the eldest daughter of Charles and Beatrice, became the wife of Robert of Béthune in 1265, but she died four years later.

* Beatrice, her younger sister, married Philip, the titular Latin emperor, in 1273.

* Charles II, Charles's eldest son and namesake was granted the

All records show that Charles was a faithful husband and a caring father. His first wife, Beatrice of Provence, gave birth to at least six children. According to contemporaneous gossips, she persuaded Charles to claim the Kingdom of Sicily, because she wanted to wear a crown like her sisters. Before she died in July 1267, she had willed the usufruct of Provence to Charles.

* Blanche, the eldest daughter of Charles and Beatrice, became the wife of Robert of Béthune in 1265, but she died four years later.

* Beatrice, her younger sister, married Philip, the titular Latin emperor, in 1273.

* Charles II, Charles's eldest son and namesake was granted the

Around 1310, the Florentine historian,

Around 1310, the Florentine historian,

Capetian dynasty

The Capetian dynasty (; french: Capétiens), also known as the House of France, is a dynasty of Frankish origin, and a branch of the Robertians. It is among the largest and oldest royal houses in Europe and the world, and consists of Hugh Cape ...

and the founder of the second House of Anjou. He was Count of Provence

The land of Provence has a history quite separate from that of any of the larger nations of Europe. Its independent existence has its origins in the frontier nature of the dukedom in Merovingian Gaul. In this position, influenced and affected by ...

(1246–85) and Forcalquier

Forcalquier (; oc, Forcauquier, ) is a commune in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department in southeastern France.

Forcalquier is located between the Lure and Luberon mountain ranges, about south of Sisteron and west of the Durance river. D ...

(1246–48, 1256–85) in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, Count of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertians ...

and Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

(1246–85) in France; he was also King of Sicily (1266–85) and Prince of Achaea

The Prince of Achaea was the ruler of the Principality of Achaea, one of the crusader states founded in Greece in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204). Though more or less autonomous, the principality was never a fully independent s ...

(1278–85). In 1272, he was proclaimed King of Albania

While the medieval Capetian House of Anjou, Angevin Kingdom of Albania (medieval), Kingdom of Albania was a monarchy, it did not encompass fully the entirety of the modern state of Albania and was ended soon by the Albanian nobles by 1282 when the ...

, and in 1277 he purchased a claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establishe ...

.

The youngest son of Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 – 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (french: Le Lion), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As prince, he invaded England on 21 May 1216 and was excommunicated by a papal legate on 29 May 1216. On 2 June 1216 ...

and Blanche of Castile

Blanche of Castile ( es, Blanca de Castilla; 4 March 1188 – 27 November 1252) was Queen of France by marriage to Louis VIII. She acted as regent twice during the reign of her son, Louis IX: during his minority from 1226 until 1234, and during ...

, Charles was destined for a Church career until the early 1240s. He acquired Provence and Forcalquier through his marriage to their heiress, Beatrice. His attempts to restore central authority brought him into conflict with his mother-in-law, Beatrice of Savoy

Beatrice of Savoy (c. 1198 – c. 1267) was Countess consort of Provence by her marriage to Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence. She served as regent of her birth country Savoy during the absence of her brother in 1264.

Early life

She was th ...

, and the nobility. Charles received Anjou and Maine from his brother, Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

, in appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much o ...

. He accompanied Louis during the Seventh Crusade to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Shortly after he returned to Provence in 1250, Charles forced three wealthy autonomous cities Marseilles, Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province of ...

and Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

to acknowledge his suzerainty.

Charles supported Margaret II, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut, against her eldest son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, in exchange for Hainaut in 1253. Two years later Louis IX persuaded him to renounce the county, but compensated him by instructing Margaret to pay him 160,000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

. Charles forced the rebellious Provençal nobles and towns into submission and expanded his suzerainty over a dozen towns and lordships in the Kingdom of Arles

The Kingdom of Burgundy, known from the 12th century as the Kingdom of Arles, also referred to in various context as Arelat, the Kingdom of Arles and Vienne, or Kingdom of Burgundy-Provence, was a realm established in 933 by the merger of the king ...

. In 1263, after years of negotiations, he accepted the offer of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

to seize the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

from the Hohenstaufens

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty ...

. This kingdom included, in addition to the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, southern Italy to well north of Naples and was known as the Regno. Pope Urban IV

Pope Urban IV ( la, Urbanus IV; c. 1195 – 2 October 1264), born Jacques Pantaléon, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1261 to his death. He was not a cardinal; only a few popes since his time hav ...

declared a crusade against the incumbent Manfred of Sicily

Manfred ( scn, Manfredi di Sicilia; 123226 February 1266) was the last King of Sicily from the Hohenstaufen dynasty, reigning from 1258 until his death. The natural son of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, Manfred became regent over the ...

and assisted Charles in raising funds for the military campaign.

Charles was crowned king in Rome on 5 January 1266. He annihilated Manfred's army and occupied the Regno almost without resistance. His victory over Manfred's young nephew, Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (german: link=no, Konradin, it, Corradino), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke ...

, at the Battle of Tagliacozzo

The Battle of Tagliacozzo was fought on 23 August 1268 between the Ghibelline supporters of Conradin of Hohenstaufen and the Guelph army of Charles of Anjou. The battle represented the last act of Hohenstaufen power in Italy. The capture and ...

in 1268 strengthened his rule. In 1270 he took part in the Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any ...

organized by Louis IX, and forced the Hafsid Caliph of Tunis to pay a yearly tribute to him. Charles's victories secured his undisputed leadership among the Papacy's Italian partisans (known as Guelphs

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rival ...

), but his influence on papal election

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the Apostolic succession, apostolic successor of Saint ...

s and his strong military presence in Italy disturbed the popes. They tried to channel his ambitions towards other territories and assisted him in acquiring claims to Achaea, Jerusalem and Arles through treaties. In 1281 Pope Martin IV

Pope Martin IV ( la, Martinus IV; c. 1210/1220 – 28 March 1285), born Simon de Brion, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 February 1281 to his death on 28 March 1285. He was the last French pope to have ...

authorised Charles to launch a crusade against the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Charles's ships were gathering at Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

, ready to begin the campaign when the Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers ( it, Vespri siciliani; scn, Vespiri siciliani) was a successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out at Easter 1282 against the rule of the French-born king Charles I of Anjou, who had ruled the Kingdom of S ...

rebellion broke out on 30March 1282 which put an end to Charles's rule on the island of Sicily. He was able to defend the mainland territories (or the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

) with the support of France and the Holy See. Charles died while making preparations for an invasion of Sicily.

Early life

Childhood

Charles was the youngest child of KingLouis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 – 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (french: Le Lion), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As prince, he invaded England on 21 May 1216 and was excommunicated by a papal legate on 29 May 1216. On 2 June 1216 ...

and Blanche of Castile

Blanche of Castile ( es, Blanca de Castilla; 4 March 1188 – 27 November 1252) was Queen of France by marriage to Louis VIII. She acted as regent twice during the reign of her son, Louis IX: during his minority from 1226 until 1234, and during ...

. The date of his birth has not survived, but he was probably a posthumous

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award - an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication – material published after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1987

* ...

son, born in early 1227. Charles was his only surviving son to be "born in the purple

Traditionally, born in the purple (sometimes "born to the purple") was a category of members of royal families born during the reign of their parent. This notion was later loosely expanded to include all children born of prominent or high-ranking ...

" (after his father's coronation), a fact he often emphasised in his youth, as the contemporaneous chronicler

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

noted in his . He was the first Capet

The House of Capet (french: Maison capétienne) or the Direct Capetians (''Capétiens directs''), also called the House of France (''la maison de France''), or simply the Capets, ruled the Kingdom of France from 987 to 1328. It was the most s ...

ian to be named for Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

.

Louis VIII died in November 1226 and his eldest son, Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

, succeeded him. The late King willed that his youngest sons were to be prepared for a career in the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The details of Charles's tuition are unknown, but he received a good education. He understood the principal Catholic doctrines and could identify errors in Latin texts. His passion for poetry, medical sciences and law is well documented.

Charles said that their mother had a strong impact on her children's education. In reality, Blanche was fully engaged in state administration, and could likely spare little time for her youngest children. Charles lived at the court of a brother, Robert I, Count of Artois

Robert I (25 September 1216 – 8 February 1250), called the Good, was the first Count of Artois. He was the fifth (and second surviving) son of King Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile.

Life

He received Artois as an appanage, in accordan ...

, from 1237. About four years later he was put into the care of his youngest brother, Alphonse, Count of Poitiers

Alphonse or Alfonso (11 November 122021 August 1271) was the count of Poitou from 1225 and count of Toulouse (as such called Alphonse II) from 1249. As count of Toulouse, he also governed the Marquisate of Provence.

Birth and early life

Born at P ...

. His participation in his brothers' military campaign against Hugh X of Lusignan

Hugh X de Lusignan, Hugh V of La Marche or Hugh I of Angoulême (c. 1183 – c. 5 June 1249, Angoulême) was Seigneur de Lusignan and Count of La Marche in November 1219 and was Count of Angoulême by marriage. He was the son of Hugh IX ...

, Count of La Marche

The County of La Marche (; oc, la Marcha) was a medieval French county, approximately corresponding to the modern ''département'' of Creuse.

La Marche first appeared as a separate fief about the middle of the 10th century, when William III, D ...

, in 1242 showed that he was no longer destined for a Church career.

Provence and Anjou

Raymond Berengar V of Provence

Ramon Berenguer V (french: Raimond-Bérenger; 1198 – 19 August 1245) was a member of the House of Barcelona who ruled as count of Provence and Forcalquier. He was the first count of Provence to live in the county in more than one hundred years ...

died in August 1245, bequeathing Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

and Forcalquier

Forcalquier (; oc, Forcauquier, ) is a commune in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department in southeastern France.

Forcalquier is located between the Lure and Luberon mountain ranges, about south of Sisteron and west of the Durance river. D ...

to his youngest daughter, Beatrice, allegedly because he had given generous dowries

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

to her three sisters. The dowries were actually not fully discharged, causing two of her sisters, Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

(Louis IX's wife) and Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was introd ...

(the wife of Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

), to believe that they had been unlawfully disinherited. Their mother, Beatrice of Savoy

Beatrice of Savoy (c. 1198 – c. 1267) was Countess consort of Provence by her marriage to Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence. She served as regent of her birth country Savoy during the absence of her brother in 1264.

Early life

She was th ...

, claimed that Raymond Berengar had willed the usufruct

Usufruct () is a limited real right (or ''in rem'' right) found in civil-law and mixed jurisdictions that unites the two property interests of ''usus'' and ''fructus'':

* ''Usus'' (''use'') is the right to use or enjoy a thing possessed, directl ...

of Provence to her.

The Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty ...

Emperor Frederick II

Frederick II (German: ''Friedrich''; Italian: ''Federico''; Latin: ''Federicus''; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusa ...

(whom Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

had recently excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

for his alleged "crimes against the Church"), Count Raymond VII of Toulouse and other neighbouring rulers proposed themselves or their sons as husbands for the young Countess. Her mother put her under the protection of the Holy See. Louis IX and Margaret suggested that Beatrice should be given in marriage to Charles. To secure the support of France against Frederick II, Pope Innocent IV accepted their proposal. Charles hurried to Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Ais de Provença in classical norm, or in Mistralian norm, ; la, Aquae Sextiae), or simply Aix ( medieval Occitan: ''Aics''), is a city and commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. ...

at the head of an army to prevent other suitors from invading Provence, and married Beatrice on 31January 1246. Provence was a part of the Kingdom of Arles

The Kingdom of Burgundy, known from the 12th century as the Kingdom of Arles, also referred to in various context as Arelat, the Kingdom of Arles and Vienne, or Kingdom of Burgundy-Provence, was a realm established in 933 by the merger of the king ...

and so of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, but Charles never swore fealty to the emperor. He ordered a survey of the counts' rights and revenues, outraging both his subjects and his mother-in-law, who regarded this action as an attack against her rights.

Being a younger child, destined for a church career, Charles had not received an appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much o ...

(a hereditary county or duchy) from his father. Louis VIII had willed that his fourth son, John, should receive Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

* County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duk ...

and Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

upon reaching the age of majority, but John died in 1232. Louis IX knighted Charles at Melun

Melun () is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region, north-central France. It is located on the southeastern outskirts of Paris, about from the kilome ...

in May 1246 and three months later bestowed Anjou and Maine on him. Charles rarely visited his two counties and appointed bailli

A bailiff (french: bailli, ) was the king's administrative representative during the ''ancien régime'' in northern France, where the bailiff was responsible for the application of justice and control of the administration and local finances in h ...

es (or regents) to administer them.

While Charles was absent from Provence, Marseilles, Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province of ...

and Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

three wealthy cities, directly subject to the emperorformed a league and appointed a Provençal nobleman, Barral of Baux

Barral of Baux (died 1268) was Viscount of Marseilles and Lord of Baux. He was the son of Hugh III of Baux, Viscount of Marseilles, and Barrale.

Career

Barral came to oppose the Albigensian Crusade, and invaded the Comtat Venaissin in 1234 in ...

, as the commander of their combined armies. Charles's mother-in-law put the disobedient Provençals under her protection. Charles could not deal with the rebels as he was about to join his brother's crusade. To pacify his mother-in-law he acknowledged her right to rule Forcalquier and granted a third of his revenues from Provence to her.

Seventh Crusade

In December 1244 Louis IX took a vow to lead a crusade. Ignoring their mother's strong opposition, his three brothersRobert, Alphonse and Charlesalso took the cross. Preparations for the crusade lasted for years, with the crusaders embarking at

In December 1244 Louis IX took a vow to lead a crusade. Ignoring their mother's strong opposition, his three brothersRobert, Alphonse and Charlesalso took the cross. Preparations for the crusade lasted for years, with the crusaders embarking at Aigues-Mortes

Aigues-Mortes (; oc, Aigas Mòrtas) is a commune in the Gard department in the Occitania region of southern France. The medieval city walls surrounding the city are well preserved. Situated on the junction of the Canal du Rhône à Sète a ...

on 25August 1248. After spending several months in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

they invaded Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

on 5June 1249. They captured Damietta

Damietta ( arz, دمياط ' ; cop, ⲧⲁⲙⲓⲁϯ, Tamiati) is a port city and the capital of the Damietta Governorate in Egypt, a former bishopric and present multiple Catholic titular see. It is located at the Damietta branch, an easter ...

and decided to attack Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

in November. During their advance Louis's biographer Jean de Joinville

Jean de Joinville (, c. 1 May 1224 – 24 December 1317) was one of the great chroniclers of medieval France. He is most famous for writing the ''Life of Saint Louis'', a biography of Louis IX of France that chronicled the Seventh Crusade.''V ...

noted Charles's personal courage which saved dozens of crusaders' lives. Robert of Artois died fighting against the Egyptians at Al Mansurah. His three brothers survived, but they had to abandon the campaign. While withdrawing from Egypt, they fell into captivity on 6April 1250. The Egyptians released Louis, Charles and Alphonse in exchange of 800,000 bezant

In the Middle Ages, the term bezant (Old French ''besant'', from Latin ''bizantius aureus'') was used in Western Europe to describe several gold coins of the east, all derived ultimately from the Roman ''solidus''. The word itself comes from th ...

s and the surrender of Damietta on 6May. During their voyage to Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

, Charles outraged Louis by gambling while the king was mourning Robert's death. Louis remained in the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

, but Charles returned to France in October 1250.

Wider ambitions

Conflicts and consolidation

Charles's officers continued the survey of the counts' rights and revenues in Provence, provoking a new rebellion during his absence. On his return he applied both diplomacy and military force to deal with them. TheArchbishop of Arles

The former French Catholic Archbishopric of Arles had its episcopal see in the city of Arles, in southern France.Bishop of Digne

The Diocese of Digne (Latin: ''Dioecesis Diniensis''; French: ''Diocèse de Digne'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in France. Erected in the 4th century as the Diocese of Digne, the diocese has bee ...

ceded their secular rights in the two towns to Charles in 1250. He received military assistance from his brother, Alphonse. Arles was the first town to surrender to them in April 1251. In May they forced Avignon to acknowledge their joint rule. A month later Barral of Baux also capitulated. Marseilles was the only town to resist for several months, but it also sought peace in July 1252. Its burghers acknowledged Charles as their lord, but retained their self-governing bodies.

Charles's officials continued to ascertain his rights, visiting each town and holding public enquiries to obtain information about all claims. The count's salt monopoly (or ) was introduced in the whole county. Income from the salt trade made up about 50% of state revenues by the late 1250s. Charles abolished local tolls and promoted shipbuilding and

Charles's officials continued to ascertain his rights, visiting each town and holding public enquiries to obtain information about all claims. The count's salt monopoly (or ) was introduced in the whole county. Income from the salt trade made up about 50% of state revenues by the late 1250s. Charles abolished local tolls and promoted shipbuilding and grain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other ...

. He ordered the issue of new coins, called , to enable the use of the local currency in smaller transactions.

Emperor Frederick II, who was also the ruler of Sicily, died in 1250. The Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

, also known as the Regno, included the island of Sicily and southern Italy nearly as far as Rome. Pope Innocent IV claimed that the Regno had reverted to the Holy See. The Pope first offered it to Richard of Cornwall

Richard (5 January 1209 – 2 April 1272) was an English prince who was King of the Romans from 1257 until his death in 1272. He was the second son of John, King of England, and Isabella, Countess of Angoulême. Richard was nominal Count of Po ...

, but Richard did not want to fight against Frederick's son, Conrad IV of Germany

Conrad (25 April 1228 – 21 May 1254), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was the only son of Emperor Frederick II from his second marriage with Queen Isabella II of Jerusalem. He inherited the title of King of Jerusalem (as Conrad II) up ...

. Then the Pope proposed to enfeoff

In the Middle Ages, especially under the European Feudalism, feudal system, feoffment or enfeoffment was the deed by which a person was given land in exchange for a Fealty, pledge of service. This mechanism was later used to avoid restrictions o ...

Charles with the kingdom. Charles sought instructions from Louis IX, who forbade him to accept the offer, because he regarded Conrad as the lawful ruler. After Charles informed the Holy See on 30October 1253 that he would not accept the Regno, the Pope offered it to Edmund of Lancaster

Edmund, Earl of Lancaster and Earl of Leicester (16 January 12455 June 1296) nicknamed Edmund Crouchback was a member of the House of Plantagenet. He was the second surviving son of King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence. In his chi ...

.

Queen Blanche, who had administered France during Louis' crusade, died on 1December 1252. Louis made Alphonse and Charles co-regents, so that he could remain in the Holy Land. Margaret II, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut had come into conflict with her son by her first marriage, John of Avesnes. After her sons by her second marriage were captured in July 1253, she needed foreign assistance to secure their release. Ignoring Louis IX's 1246 ruling that Hainaut should pass to John, she promised the county to Charles. He accepted the offer and invaded Hainaut, forcing most local noblemen to swear fealty to him. After his return to France, Louis IX insisted that his ruling was to be respected. In November 1255 he ordered Charles to restore Hainaut to Margaret, but her sons were obliged to swear fealty to Charles. Louis also ruled that she was to pay 160,000 marks to Charles over the following 13 years.

Charles returned to Provence, which had again become restive. His mother-in-law continued to support the rebellious Boniface of Castellane and his allies, but Louis IX persuaded her to return Forcalquier to Charles and relinquish her claims for a lump sum payment from Charles and a pension from Louis in November 1256. A coup by Charles's supporters in Marseilles resulted in the surrender of all political powers there to his officials. Charles continued to expand his power along the borders of Provence in the next four years. He received territories in the Lower Alps from the Dauphin of Vienne. Raymond I of Baux

Raymond is a male given name. It was borrowed into English from French (older French spellings were Reimund and Raimund, whereas the modern English and French spellings are identical). It originated as the Germanic ᚱᚨᚷᛁᚾᛗᚢᚾᛞ ( ...

, Count of Orange, ceded the title of regent of the Kingdom of Arles to him. The burghers of Cuneo

Cuneo (; pms, Coni ; oc, Coni/Couni ; french: Coni ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Northern Italy, the capital of the province of Cuneo, the fourth largest of Italy’s provinces by area.

It is located at 550 metres (1,804 ft) in ...

a town strategically located on the routes from Provence to Lombardysought Charles's protection against Asti

Asti ( , , ; pms, Ast ) is a ''comune'' of 74,348 inhabitants (1-1-2021) located in the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy, about east of Turin in the plain of the Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and it is deemed t ...

in July 1259. Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scottish people, Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed i ...

, Cherasco

Cherasco is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Cuneo in the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian ...

, Savigliano

Savigliano (Savijan in Piedmontese) is a ''comune'' of Piedmont, northern Italy, in the Province of Cuneo, about south of Turin by rail.

It is home to ironworks, foundries, locomotive works (once owned by Fiat Ferroviaria, now by Alstom) and s ...

and other nearby towns acknowledged his rule. The rulers of Mondovì

Mondovì (; pms, Ël Mondvì , la, Mons Regalis) is a town and ''comune'' (township) in Piedmont, northern Italy, about from Turin. The area around it is known as the Monregalese.

The town, located on the Monte Regale hill, is divided into ...

, Ceva

Ceva, the ancient Ceba, is a small Italian town in the province of Cuneo, region of Piedmont, east of Cuneo. It lies on the right bank of the Tanaro on a wedge of land between that river and the Cevetta stream.

History

In the pre-Roman period th ...

, Biandrate

Biandrate (Piedmontese: ''Biandrà'', Lombard: ''Biandraa'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Novara in the Italian region Piedmont, located about northeast of Turin and about west of Novara.

History

Archaeological findings h ...

and Saluzzo

Saluzzo (; pms, Salusse ) is a town and former principality in the province of Cuneo, in the Piedmont region, Italy.

The city of Saluzzo is built on a hill overlooking a vast, well-cultivated plain. Iron, lead, silver, marble, slate etc. are fo ...

did homage to him.

Emperor Frederick II's illegitimate son, Manfred

''Manfred: A dramatic poem'' is a closet drama written in 1816–1817 by Lord Byron. It contains supernatural elements, in keeping with the popularity of the ghost story in England at the time. It is a typical example of a Gothic fiction.

Byr ...

, had been crowned king of Sicily in 1258. After the English barons had announced that they opposed a war against Manfred, Pope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death in 1261.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne (now in the Province of Rome), he ...

annulled the 1253 grant of Sicily to Edmund of Lancaster. Alexander's successor, Pope Urban IV

Pope Urban IV ( la, Urbanus IV; c. 1195 – 2 October 1264), born Jacques Pantaléon, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1261 to his death. He was not a cardinal; only a few popes since his time hav ...

, was determined to put an end to the Emperor's rule in Italy. He sent his notary, Albert of Parma, to Paris to negotiate with Louis IX for Charles to be placed on the Sicilian throne. Charles met with the Pope's envoy in early 1262.

Taking advantage of Charles's absence, Boniface of Castellane stirred up a new revolt in Provence. The burghers of Marseilles expelled Charles's officials, but Barral of Baux stopped the spread of the rebellion before Charles's return. Charles renounced Ventimiglia

Ventimiglia (; lij, label=Intemelio, Ventemiglia , lij, label= Genoese, Vintimiggia; french: Vintimille ; oc, label= Provençal, Ventemilha ) is a resort town in the province of Imperia, Liguria, northern Italy. It is located southwest of ...

in favour of the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Lat ...

to secure her neutrality. He defeated the rebels and forced Castellane into exile. The mediation of James I of Aragon

James I the Conqueror ( es, Jaime el Conquistador, ca, Jaume el Conqueridor; 2 February 1208 – 27 July 1276) was King of Aragon and Lord of Montpellier from 1213 to 1276; King of Majorca from 1231 to 1276; and Valencia from 1238 to 1276 ...

brought about a settlement with Marseilles: its fortifications were dismantled and the townspeople surrendered their arms, but the town retained its autonomy.

Conquest of the Regno

Louis IX decided to support Charles's military campaign in Italy in May 1263. Pope Urban IV promised to proclaim a crusade against Manfred, while Charles pledged that he would not accept any offices in the Italian towns. Manfred staged a coup in Rome, but theGuelphs

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rival ...

elected Charles senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

(or the head of the civil government of Rome). He accepted the office, at which a group of cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

requested that the Pope revoke the agreement with him, but the Pope, being otherwise defenceless against Manfred, could not break with Charles.

In the spring of 1264 Cardinals Simon of Brie and Guy Foulquois were sent to France to reach a compromise and start raising support for the crusade. Charles sent troops to Rome to protect the Pope against Manfred's allies. At Foulquois' request, Charles's sister-in-law Margaret (who had not abandoned her claims to her dowry) pledged that she would not take actions against Charles during his absence. Foulquois also persuaded the French and Provençal prelates to offer financial support for the crusade. Pope Urban died before the final agreement was concluded. Charles made arrangements for his campaign against Sicily during the interregnum; he concluded agreements to secure his army's route across Lombardy and had the leaders of the Provençal rebels executed.

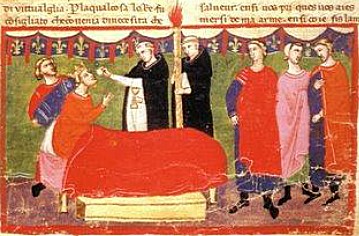

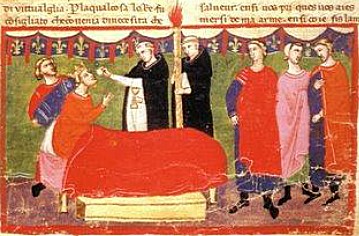

Foulquois was elected pope in February 1265; he soon confirmed Charles's senatorship and urged him to come to Rome. Charles agreed that he would hold the Kingdom of Sicily as the popes' vassal for an annual tribute of 8,000 ounces of gold. He also promised that he would never seek the imperial title. He embarked at Marseilles on 10May and landed at Ostia ten days later. He was installed as senator on 21June and four cardinals invested him with the Regno a week later. To finance further military actions he borrowed money from Italian bankers with the Pope's assistance, who had authorised him to pledge Church property. Five cardinals crowned him king of Sicily on 5January 1266. The crusaders from France and Provencereportedly 6,000 fully equipped mounted warriors, 600 mounted bowmen and 20,000 foot soldiersarrived in Rome ten days later.

Charles decided to invade southern Italy without delay, because he was unable to finance a lengthy campaign. He left Rome on 20January 1266. He marched towards

Charles decided to invade southern Italy without delay, because he was unable to finance a lengthy campaign. He left Rome on 20January 1266. He marched towards Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, but changed his strategy after learning of a muster of Manfred's forces near Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrusc ...

. He led his troops across the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

towards Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and ''comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

. Manfred also hurried to the town and reached it before Charles. Worried that further delays might endanger his subjects' loyalty, Manfred attacked Charles's army, then in disarray from the crossing of the hills, on 26February 1266. In the ensuing battle, Manfred's army was defeated and he was killed.

Resistance throughout the Regno collapsed and towns surrendered even before Charles's troops reached them. The Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s of Lucera

Lucera ( Lucerino: ) is an Italian city of 34,243 inhabitants in the province of Foggia in the region of Apulia, and the seat of the Diocese of Lucera-Troia.

Located upon a flat knoll in the Tavoliere Plains, near the foot of Daunian Mountain ...

– a Muslim colony established during Frederick II's reign – paid homage to him. His commander, Philip of Montfort, took control of the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. Manfred's widow, Helena of Epirus, and their children were captured. Charles laid claim to her dowry – the island of Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

and the region of Durazzo (now Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the second most populous city of the Republic of Albania and seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is located on a flat plain along the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast between the mouths of ...

in Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

) – by right of conquest. His troops seized Corfu before the end of the year.

Conradin

Charles was lenient with Manfred's supporters, but they did not believe that this conciliatory policy could last. They knew that he had promised to return estates to the Guelph lords expelled from the Regno. Neither could Charles gain the commoners' loyalty, partly because he continued enforcing the despite the popes declaring it an illegal charge. He introduced a ban on the use of foreign currency in large transactions and made a profit of the compulsory exchange of foreign coinage for locally minted currency. He also traded in grain, spices and sugar, through a joint venture with Pisan merchants. Pope Clement censured Charles for his methods of state administration, describing him as an arrogant and obstinate monarch. The consolidation of Charles's power in northern Italy also alarmed Clement. To appease the Pope, Charles resigned his senatorship in May 1267. His successors, Conrad Monaldeschi andLuca Savelli

Luca Savelli was a Roman senator who in 1234 sacked the Lateran. He was born in 1190, died in 1266, and was married to Vana Aldobrandeschi. Luca's tomb is found at the Santa Maria in Aracoeli "Our Lady of The Heavenly Altar", along with his wi ...

, demanded the re-payment of the money that Charles and the Pope had borrowed from the Romans.

Victories by the Ghibellines

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalr ...

, the imperial family's supporters, forced the Pope to ask Charles to send his troops to Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; it, Toscana ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (''Firenze'').

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, art ...

. Charles's troops ousted the Ghibellines from Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

in April 1267. After being elected the Podestà

Podestà (, English: Potestate, Podesta) was the name given to the holder of the highest civil office in the government of the cities of Central and Northern Italy during the Late Middle Ages. Sometimes, it meant the chief magistrate of a city ...

(ruler) of Florence and Lucca

Lucca ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its province has a population of 383,957.

Lucca is known as one o ...

for seven years, Charles hurried to Tuscany. Charles's expansionism along the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

's borders alarmed Pope Clement and he decided to change the direction of Charles's ambitions. The Pope summoned him to Viterbo

Viterbo (; Viterbese: ; lat-med, Viterbium) is a city and ''comune'' in the Lazio region of central Italy, the capital of the province of Viterbo.

It conquered and absorbed the neighboring town of Ferento (see Ferentium) in its early history. ...

, forcing him to promise that he would abandon all claims to Tuscany in three years. He persuaded Charles to conclude agreements with William of Villehardouin

William of Villehardouin (french: Guillaume de Villehardouin; Kalamata, 1211 – 1 May 1278) was the fourth prince of Achaea in Frankish Greece, from 1246 to 1278. The younger son of Prince Geoffrey I, he held the Barony of Kalamata ...

, Prince of Achaea

The Prince of Achaea was the ruler of the Principality of Achaea, one of the crusader states founded in Greece in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204). Though more or less autonomous, the principality was never a fully independent s ...

, and the titular Latin Emperor

The Latin Emperor was the ruler of the Latin Empire, the historiographical convention for the Crusader realm, established in Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade (1204) and lasting until the city was recovered by the Byzantine Greeks in 1261 ...

Baldwin II in late May. According to the first treaty, Villehardouin acknowledged Charles's suzerainty and made Charles's younger son, Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, his heir, also stipulating that Charles would inherit Achaea if Philip died childless. Baldwin confirmed the first agreement and renounced his claims to suzerainty over his vassals in favour of Charles. Charles pledged that he would assist Baldwin in recapturing Constantinople from the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

, in exchange for one third of the conquered lands.

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November. Manfred's staunchest supporters had meanwhile fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade Conrad IV's 15-year-old son

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November. Manfred's staunchest supporters had meanwhile fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade Conrad IV's 15-year-old son Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (german: link=no, Konradin, it, Corradino), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke ...

to assert his hereditary right to the Kingdom of Sicily. After Conradin accepted their proposal, Manfred's former vicar in Sicily, Conrad Capece, returned to the island and stirred up a revolt. At Capece's request Muhammad I al-Mustansir

Muhammad I al-Mustansir (; ) was the second ruler of the Hafsid dynasty in Ifriqiya and the first to claim the title of Khalif. Al-Mustansir concluded a peace agreement to end the Eighth Crusade launched by Louis IX of France in 1270. Muhamma ...

, the Hafsid caliph of Tunis, allowed Manfred's former ally, Frederick of Castile, to invade Sicily from North Africa. Frederick's brother, Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

who had been elected senator of Romealso offered support to Conradin. Henry had been Charles's friend, but Charles had failed to repay a loan to him.

Conradin left Bavaria in September 1267. His supporters' revolt was spreading from Sicily to Calabria; the Saracens of Lucera also rose up. Pope Clement urged Charles to return to the Regno, but he continued his campaign in Tuscany until March 1268, when he met with the Pope. In April, the Pope made Charles imperial vicar

An imperial vicar (german: Reichsvikar) was a prince charged with administering all or part of the Holy Roman Empire on behalf of the emperor. Later, an imperial vicar was invariably one of two princes charged by the Golden Bull with administering ...

of Tuscany "during the vacancy of the empire", a move of dubious legality. Charles marched to southern Italy and laid siege to Lucera, but he then had to hurry north to prevent Conradin's invasion of Abruzzo

Abruzzo (, , ; nap, label=Neapolitan language, Abruzzese Neapolitan, Abbrùzze , ''Abbrìzze'' or ''Abbrèzze'' ; nap, label=Sabino dialect, Aquilano, Abbrùzzu; #History, historically Abruzzi) is a Regions of Italy, region of Southern Italy wi ...

in late August. At the Battle of Tagliacozzo

The Battle of Tagliacozzo was fought on 23 August 1268 between the Ghibelline supporters of Conradin of Hohenstaufen and the Guelph army of Charles of Anjou. The battle represented the last act of Hohenstaufen power in Italy. The capture and ...

, on 23August 1268, it appeared that Conradin had won the day, but a sudden charge by Charles's reserve routed Conradin's army.

The burghers of Potenza

Potenza (, also , ; , Potentino dialect: ''Putenz'') is a ''comune'' in the Southern Italian region of Basilicata (former Lucania).

Capital of the Province of Potenza and the Basilicata region, the city is the highest regional capital and one ...

, Aversa

Aversa () is a city and ''comune'' in the Province of Caserta in Campania, southern Italy, about 24 km north of Naples. It is the centre of an agricultural district, the ''Agro Aversano'', producing wine and cheese (famous for the typical bu ...

and other towns in Basilicata

it, Lucano (man) it, Lucana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

...

and Apulia massacred their fellows who had agitated on Conradin's behalf, but the Sicilians and the Saracens of Lucera did not surrender. Charles marched to Rome where he was again elected senator in September. He appointed new officials to administer justice and collect state revenues. New coins bearing his name were struck. During the following decade, Rome was ruled by Charles's vicars, each appointed for one year.

Conradin was captured at Torre Astura 260px, The medieval coastal Tower of the Frangipani.

Torre Astura, formerly an island called by the ancients merely Astura (Greek: ), is now a peninsula in the ''comune'' of Nettuno, on the coast of Latium, Italy, at the southeast extremity of the ...

. Most of his retainers were summarily executed, but Conradin and his friend, Frederick I, Margrave of Baden

Frederick I of Baden (1249 – October 29, 1268), a member of the House of Zähringen, was Margrave of Baden and of Verona, as well as claimant Duke of Austria from 1250 until his death.Regesten der Markgrafen von Baden und Hachberg, 1050-1515. ...

, were brought to trial for robbery and treason in Naples. They were sentenced to death and beheaded on 29October. Conrad of Antioch

Conrad of Antioch ( it, Corrado d'Antiochia; born 1240/41, died after 1312) was a scion of an illegitimate branch of the imperial Staufer dynasty and a nobleman of the Kingdom of Sicily. He was the eldest son of Frederick of Antioch, imperial vic ...

was Conradin's only partisan to be released, but only after his wife threatened to execute the Guelph lords she held captive in her castle. The Ghibelline noblemen of the Regno fled to the court of Peter III of Aragon

Peter III of Aragon ( November 1285) was King of Aragon, King of Valencia (as ), and Count of Barcelona (as ) from 1276 to his death. At the invitation of some rebels, he conquered the Kingdom of Sicily and became King of Sicily in 1282, pres ...

, who had married Manfred's daughter, Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

*Konstanz, Germany, sometimes written as Constance in English

*Constance Bay, Ottawa, Canada

* Constance, Kentucky

* Constance, Minnesota

* Constance (Portugal)

* Mount Constance, Washington State

People

* Consta ...

.

Mediterranean empire

Italy

Charles's wife, Beatrice of Provence, had died in July 1267. The widowed Charles marriedMargaret of Nevers

Margaret of Nevers (french: link=no, Marguerite; December 1393 – February 1442), also known as Margaret of Burgundy, was Dauphine of France and Duchess of Guyenne as the daughter-in-law of King Charles VI of France. A pawn in the dynastic strug ...

in November 1268. She was co-heiress to her father, Odo

Odo or ODO may refer to:

People

* Odo, a given name; includes a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Franklin Odo (born 1939), Japanese-American historian

* Seikichi Odo (1927–2002), Japanese karateka

* Yuya Odo (born 1990), J ...

, the eldest son of Hugh IV, Duke of Burgundy

Hugh IV of Burgundy (9 March 1213 – 27 or 30 October 1272) was Duke of Burgundy between 1218 and 1272 and from 1266 until his death was titular King of Thessalonica. Hugh was the son of Odo III, Duke of Burgundy and Alice de Vergy.

Issue

Hugh m ...

. Pope Clement died on 29November 1268. The papal vacancy lasted for three years, which strengthened Charles's authority in Italy, but it also deprived him of the ecclesiastic support that only a pope could provide.

Charles returned to Lucera to personally direct its siege in April 1269. The Saracens and the Ghibellines who had escaped to the town resisted until starvation forced them to surrender in August 1269. Charles sent Philip and Guy of Montfort to Sicily to force the rebels there into submission, but they could only capture Augusta. Charles made William l'Estandart the commander of the army in Sicily in August 1269. L'Estandart captured Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one of ...

, forcing Frederick of Castile and Frederick Lancia to seek refuge in Tunis. After L'Estandart's subsequent victory at Sciacca

Sciacca (; Greek language, Greek: ; Latin: Thermae Selinuntinae, Thermae Selinuntiae, Thermae, Aquae Labrodes and Aquae Labodes) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Agrigento on the southwestern coast of Sicily, southern Italy. It has vi ...

, only Capece resisted, but he also had to surrender in early 1270.

Charles's troops forced Siena and Pisathe last towns to resist him in Tuscanyto sue for peace in August 1270. He granted privileges to the Tuscan merchants and bankers which strengthened their position in the Regno. His influence was declining in Lombardy, because the Lombard towns no longer feared an invasion from Germany after Conradin's death. In May 1269 Charles sent Walter of La Roche to represent him in the province, but this failed to strengthen his authority. In October Charles's officials convoked an assembly at Cremona, and invited the Lombard towns to attend. The Lombard towns accepted the invitation, but some townsMilan, Bologna, Alessandria and Tortonaonly confirmed their alliance with Charles, without acknowledging his rule.

Eighth Crusade

Louis IX never abandoned the idea of the liberation of Jerusalem, but he decided to begin his new crusade with a military campaign against Tunis. According to his confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, Louis was convinced that al-Mustansir of Tunis was ready to convert to Christianity. The 13th-century historianSaba Malaspina

Saba Malaspina (died 1297 or 1298) was an Italian historian, writer, and clergyman. Born around the mid-13th century in southern Italy, he was from a "Roman family with a strong tradition of support for the papal cause" and was the deacon (later b ...

stated that Charles persuaded Louis to attack Tunis, because he wanted to secure the payment of the tribute that the rulers of Tunis had paid to the former Sicilian monarchs.

The French crusaders embarked at Aigues-Mortes on 2July 1270; Charles departed from Naples six days later. He spent more than a month in Sicily, waiting for his fleet. By the time he landed at Tunis on 25August, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

had decimated the French army. Louis died the day Charles arrived.

The crusaders twice defeated Al-Mustansir's army, forcing him to sue for peace. According to the peace treaty, signed on 1November, Al-Mustansir agreed to fully compensate Louis' son and successor, Philip III of France

Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), called the Bold (french: le Hardi), was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned ...

, and Charles for the expenses of the military campaign and to release his Christian prisoners. He also promised to pay a yearly tribute to Charles and to expel Charles's opponents from Tunis. The gold from Tunis, along with silver from the newly opened mine at Longobucco

Longobucco is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Cosenza, in the Calabria region of southern Italy. Longobucco is one of the main municipalities of the Sila National Park and in terms of its territory is one of the largest in Calabria. It ...

, enabled Charles to mint new coins, known as , in the Regno.

Charles and Philip departed Tunis on 10November. A storm dispersed their fleet at Trapani

Trapani ( , ; scn, Tràpani ; lat, Drepanum; grc, Δρέπανον) is a city and municipality (''comune'') on the west coast of Sicily, in Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Trapani. Founded by Elymians, the city is still an impor ...

and most of Charles's galleys were lost or damaged. Genoese ships returning from the crusade were also sunk or forced to land in Sicily. Charles seized the damaged ships and their cargo, ignoring all protests from the Ghibelline authorities of Genoa. Before leaving Sicily he granted temporary tax concessions to the Sicilians, because he realised that the conquest of the island had caused much destruction.

Attempts to expand

Charles accompanied Philip III as far as Viterbo in March 1271. Here they failed to convince the cardinals to elect a new pope. Charles's brother, Alphonse of Poitiers, fell ill. Charles sent his best doctors to cure him, but Alphonse died. He claimed the major part of Alphonse's inheritance, including theMarquisate of Provence

The land of Provence has a history quite separate from that of any of the larger nations of Europe. Its independent existence has its origins in the frontier nature of the dukedom in Merovingian Gaul. In this position, influenced and affected by ...

and the County of Poitiers The County of Poitou (Latin ''comitatus Pictavensis'') was a historical region of France, consisting of the three sub-regions of Vendée

Vendée (; br, Vande) is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coa ...

, because he was Alphonse's nearest kin. After Philip III objected, he took the case to the Parlement

A ''parlement'' (), under the French Ancien Régime, was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 parlements, the oldest and most important of which was the Parlement of Paris. While both the modern Fre ...

of Paris. In 1284 the court ruled that appanages escheat

Escheat is a common law doctrine that transfers the real property of a person who has died without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in "limbo" without recognized ownership. It originally applied to a ...

ed to the French crown if their rulers died without descendants.

An earthquake destroyed the walls of Durazzo in the late 1260s or early 1270s. Charles's troops took possession of the town with the assistance of the leaders of the nearby Albanian communities. Charles concluded an agreement with the Albanian chiefs, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties in February 1272. He adopted the title of

An earthquake destroyed the walls of Durazzo in the late 1260s or early 1270s. Charles's troops took possession of the town with the assistance of the leaders of the nearby Albanian communities. Charles concluded an agreement with the Albanian chiefs, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties in February 1272. He adopted the title of King of Albania

While the medieval Angevin Kingdom of Albania was a monarchy, it did not encompass fully the entirety of the modern state of Albania and was ended soon by the Albanian nobles by 1282 when they understood that the Angevin king was not going to keep ...

and appointed Gazzo Chinardo as his vicar-general. He also sent his fleet to Achaea to defend the principality against Byzantine attacks.

Charles hurried to Rome to attend the enthronement of Pope Gregory X

Pope Gregory X ( la, Gregorius X; – 10 January 1276), born Teobaldo Visconti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 September 1271 to his death and was a member of the Secular Franciscan Order. He was ...

on 27March 1272. The new pope was determined to put an end to the conflicts between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. While in Rome Charles met with the Guelph leaders who had been exiled from Genoa. After they offered him the office of captain of the people

Captain of the People ( it, Capitano del popolo, Lombard: ''Capitani del Popol'') was an administrative title used in Italy during the Middle Ages, established essentially to balance the power and authority of the noble families of the Italian c ...

, Charles promised military assistance to them. In November 1272 Charles commanded his officials to take prisoner all Genoese within his territories, except for the Guelphs, and to seize their property. His fleet occupied Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French: ; it, Aiaccio or ; co, Aiacciu , locally: ; la, Adiacium) is a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the ''Collectivité territoriale de Corse'' (capital city of Corsica). ...

in Corsica. Pope Gregory condemned his aggressive policy, but proposed that the Genoese should elect Guelph officials. Ignoring the Pope's proposal, the Genoese made alliance with Alfonso X of Castile, William VII of Montferrat

Guillaume VII de Montferrat.

William VII (c. 1240 – 6 February 1292), called the Great Marquis ( it, il Gran Marchese), was the twelfth Marquis of Montferrat from 1253 to his death. He was also the titular King of Thessalonica.

Biography ...

and the Ghibelline towns of Lombardy in October 1273.

The conflict with Genoa prevented Charles from invading the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, but he continued to forge alliances in the Balkan Peninsula. The Bulgarian ruler, Konstantin Tih

Konstantin Tih ( bg, Константин Тих Асен) or Constantine I Tikh (Константин I), was the tsar of Bulgaria from 1257 to 1277, he was offered the throne from Mitso Asen. He led the Bulgarian Empire at a time when the nearb ...

, was the first to conclude a treaty with him in 1272 or 1273. John I Doukas of Thessaly

John I Doukas ( gr, Ἰωάννης Δούκας, Iōánnēs Doúkas), Latinized as Ducas, was an illegitimate son of Michael II Komnenos Doukas, Despot of Epirus in –1268. After his father's death, he became ruler of Thessaly from to his ow ...

and Stefan Uroš I

Stefan Uroš I ( sr-cyr, Стефан Урош I; 1223 – May 1, 1277), known as Uroš the Great (Урош Велики) was the King of Serbia from 1243 to 1276, succeeding his brother Stefan Vladislav. He was one of the most important rulers ...

, King of Serbia

This is an archontological list of Serbian monarchs, containing monarchs of the medieval principalities, to heads of state of modern Serbia.

The Serbian monarchy dates back to the Early Middle Ages. The Serbian royal titles used include Knya ...

, joined the coalition in 1273. However, Pope Gregory forbade Charles to attack, because he hoped to unify the Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

and Catholic churches with the assistance of Emperor Michael VIII.

The renowned theologian Thomas Aquinas