Charles L. McNary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Linza McNary (June 12, 1874February 25, 1944) was an American

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed successful campaign of his brother, John, for

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed successful campaign of his brother, John, for

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

politician from Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. He served in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from 1917 to 1944 and was Senate Minority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding ...

from 1933 to 1944. In the Senate, McNary helped to pass legislation that led to the construction of Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Lock and Dam consists of several run-of-the-river dam structures that together complete a span of the Columbia River between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington at River Mile 146.1. The dam is located east of Portland, Oregon, ...

on the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

, and worked on agricultural and forestry issues. He also supported many of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

programs at the beginning of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Until Mark Hatfield

Mark Odom Hatfield (July 12, 1922 – August 7, 2011) was an American politician and educator from the state of Oregon. A Republican, he served for 30 years as a United States senator from Oregon, and also as chairman of the Senate Appropr ...

surpassed his mark in 1993, he was Oregon's longest-serving senator.

McNary was the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1940

A calendar from 1940 according to the Gregorian calendar, factoring in the dates of Easter and related holidays, cannot be used again until the year 5280.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

*January ...

, on the ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

with presidential candidate Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

; both died in 1944, during what would have been their first term had they won. They lost to the Democratic ticket, composed of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, who was running for his third term as president, and Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. S ...

by just under a ten-point margin. McNary was a justice of the Oregon Supreme Court

The Oregon Supreme Court (OSC) is the highest state court in the U.S. state of Oregon. The only court that may reverse or modify a decision of the Oregon Supreme Court is the Supreme Court of the United States.Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law is the law school of Willamette University. Located in Salem, Oregon, and founded in 1883, Willamette is the oldest law school in the Pacific Northwest. It has approximately 24 full-time law professors and e ...

, in his hometown of Salem

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

, from 1908 to 1913. Before that, he was a deputy district attorney under his brother, John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary (January 31, 1867 – October 25, 1936) was an American attorney and jurist in the state of Oregon. He served as a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of ...

, who later became a federal judge for the District of Oregon

The United States District Court for the District of Oregon (in case citations, D. Ore. or D. Or.) is the federal district court whose jurisdiction comprises the state of Oregon. It was created in 1859 when the state was admitted to the Union. ...

.

McNary died in office after unsuccessful surgery on a brain tumor. Oregon held a state funeral for him, during which his body lay in state at the Oregon State Capitol

The Oregon State Capitol is the building housing the state legislature and the offices of the governor, secretary of state, and treasurer of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is located in the state capitol, Salem. Constructed from 1936 to 1938 ...

in Salem. McNary Dam, McNary Field

McNary Field (Salem Municipal Airport) is in Marion County, Oregon, United States, two miles southeast of downtown Salem, which owns it. The airport is named for U.S. Senator Charles L. McNary.

McNary Field has had scheduled airline flights, i ...

, McNary High School

McNary High School is a public high school located in Keizer, Oregon, United States. It is named for Charles L. McNary, a U.S. Senator who was from the Keizer area.

Academics

Although McNary High School is one of eight high schools in the Sal ...

, and McNary Country Club (on land he owned) in Oregon are named in his honor. He is currently the longest serving Senate Minority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding ...

.

Early life

McNary was born on his maternal grandfather's family farm north ofSalem

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

on June 12, 1874. He was the ninth of ten children, and the third son, born to Hugh Linza McNary and Mary Margaret McNary (''née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

'' Claggett).Steve Neal, ''McNary of Oregon: A Political Biography''. Portland, OR: Western Imprints, 1985; pp. 1–2. OCLC 12214557. When the two married in 1860, Hugh McNary's father-in-law gave him a farm in what is now the city of Keizer.

McNary's father helped on the family farm, then taught school for a few years before returning to farming near Salem. When McNary's mother died in 1878, his father moved the family to Salem where he bought a general merchandise store after being unable to run the family farm because of declining health. Charles, known as Tot, began his education at a one-room school in Keizer and later attended Central School in Salem, living on North Commercial Street. Hugh McNary died in 1883, making Charlie an orphan at the age of nine.

Nina McNary became the head of the household, while other siblings took jobs in order to provide for the family.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 3–6. As a boy, Charles worked as a paperboy

A paperboy is someoneoften an older child or adolescentwho distributes printed newspapers to homes or offices on a regular route, usually by bicycle or automobile. In Western nations during the heyday of print newspapers during the early 20th ...

, in an orchard, and at other farming tasks. He met Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, a future U.S. president, who moved to Salem in 1888. He later worked in the county recorder

Recorder of deeds or deeds registry is a government office tasked with maintaining public records and documents, especially records relating to real estate ownership that provide persons other than the owner of a property with real rights over ...

's office for his brother John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary (January 31, 1867 – October 25, 1936) was an American attorney and jurist in the state of Oregon. He served as a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of ...

, who had been elected as county recorder in 1890, and for a short time attended the Capital Business College. After leaving that school, he enrolled in college preparatory classes at Willamette University

Willamette University is a private liberal arts college with locations in Salem and Portland, Oregon. Founded in 1842, it is the oldest college in the Western United States. Originally named the Oregon Institute, the school was an unaffiliated ...

, with an eye towards attending Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

or the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, ...

. During this time he met Jessie Breyman, whom he began dating, at a social club he helped start. Another member of the club was Oswald West

Oswald West (May 20, 1873 – August 22, 1960) was an American politician, a Democrat, who served most notably as the 14th Governor of Oregon.

He was called "Os West" by Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook, who described him as "by all odds the mo ...

, a future governor of Oregon

The governor of Oregon is the head of government of Oregon and serves as the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The title of governor was also applied to the office of Oregon's chief executive during the provisional and U.S. ter ...

.

Legal career

In the autumn of 1896, McNary moved toCalifornia

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

to attend Stanford, where he studied law, economics, science, and history while working as a waiter to pay for his housing. He left Stanford and returned to Oregon in 1897 after his family asked him to come home.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 9–13. Back in Salem, he read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

under the supervision of his brother John and Samuel L. Hayden, and passed the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in 1898. The brothers practiced law together in Salem as McNary & McNary, while John also served as deputy district attorney for Marion County. At this time, Charles bought the old family farm and returned it to the family. From 1909 to 1911 he served as president of the Salem Board of Trade, and in 1909 helped to organize the Salem Fruit Union, an agricultural association.

While still partnered with his brother, McNary began teaching property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual pro ...

at Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law is the law school of Willamette University. Located in Salem, Oregon, and founded in 1883, Willamette is the oldest law school in the Pacific Northwest. It has approximately 24 full-time law professors and e ...

in the spring of 1899 and courting Jessie Breyman. In 1908, he was hired as its dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

to replace John W. Reynolds. As dean, he worked to enlarge the school and secure additional classroom space. He recruited prominent local attorneys to serve on the faculty and increased the size of the school from four graduates in 1908 to 36 in 1913, his last year as dean. In his drive to make Willamette's law school one of the top programs on the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

, he had it re-located from leased space in office buildings to the university campus.

On November 19, 1902, he married Jessie Breyman, the daughter of successful Salem businessman Eugene Breyman. Jessie died on July 3, 1918, in an automobile accident south of Newberg on her way home to Salem. She had been in Oregon to attend the funeral of her mother and was returning from Portland in the Boise family's car when it flipped and crushed her. McNary spent several days in Oregon for her funeral and then returned to Washington. Charles and Jessie had no children.

State politics

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed successful campaign of his brother, John, for

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed successful campaign of his brother, John, for district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a l ...

for the third judicial district of Oregon. John then appointed Charles as his deputy, who served until 1911.

Steve Neal, McNary's biographer, describes McNary as a progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

who stuck with the Republican Party in 1910 even when many progressives left the party in favor of West, a Democrat. McNary backed the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

reforms (the initiative

In political science, an initiative (also known as a popular initiative or citizens' initiative) is a means by which a petition signed by a certain number of registered voters can force a government to choose either to enact a law or hold a pu ...

, recall

Recall may refer to:

* Recall (bugle call), a signal to stop

* Recall (information retrieval), a statistical measure

* ''ReCALL'' (journal), an academic journal about computer-assisted language learning

* Recall (memory)

* ''Recall'' (Overwatch ...

, referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, primary election

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the ...

s, and the direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

of US senators) of Oregonian William Simon U'Ren

William Simon U'Ren (January 10, 1859 – March 8, 1949) was an American lawyer and political activist. U'Ren promoted and helped pass a corrupt practices act, the presidential primary, and direct election of U.S. senators. As a progressive, U'R ...

, and he was an early supporter of public, rather than private, power companies. After West won the election, he chose McNary to be special legal counsel to Oregon's railroad commission, who urged lower passenger and freight rates.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', p. 13. Meanwhile, McNary maintained friendly relations with both progressive and conservative factions of the Oregon Republicans and with West.

In 1913, West appointed McNary to the Oregon Supreme Court

The Oregon Supreme Court (OSC) is the highest state court in the U.S. state of Oregon. The only court that may reverse or modify a decision of the Oregon Supreme Court is the Supreme Court of the United States.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', p. 19. such as an

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans, while the Senate was under Democratic control during the

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans, while the Senate was under Democratic control during the

In 1926, McNary built a new $6,000 ranch-style house, which he designed himself, along two creeks on his farm north of Salem. His estate, called "Fir Cone", featured a putting green, rose garden, tennis court, fishpond, and

In 1926, McNary built a new $6,000 ranch-style house, which he designed himself, along two creeks on his farm north of Salem. His estate, called "Fir Cone", featured a putting green, rose garden, tennis court, fishpond, and

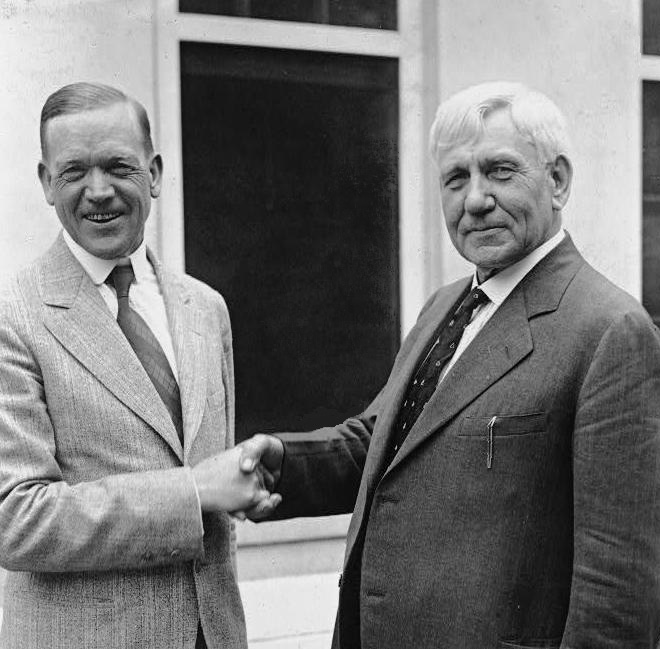

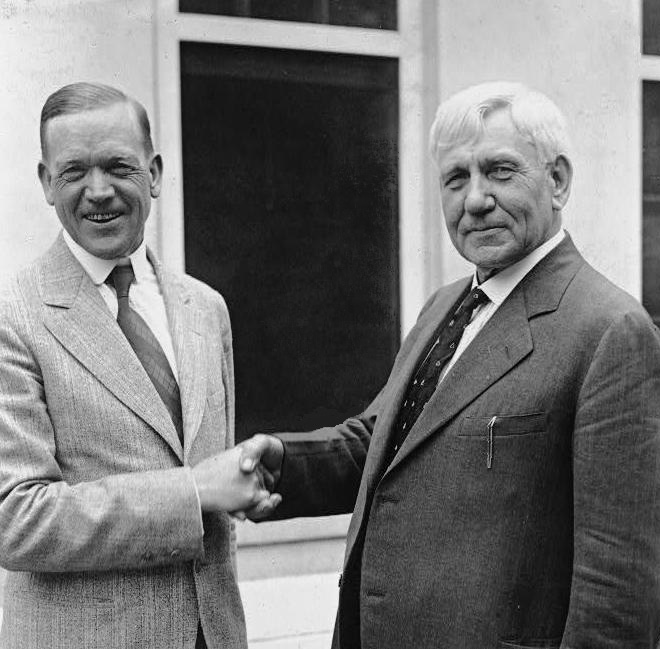

Senate Portrait

Letter to McNary from President Hoover"Memorial services held in the House of representatives and Senate of the United States, together with remarks presented in eulogy of Charles Linza McNary, late a senator from Oregon. Seventy-eighth Congress, second session."

Historic images of Charles McNary

from Salem Public Library *

Supreme Court Justices of OregonElection History of OregonHarry Lane

* , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:McNary, Charles L. 1874 births 1944 deaths Politicians from Salem, Oregon American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from Oregon Republican Party United States senators from Oregon 1940 United States vice-presidential candidates Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Oregon Republican Party chairs Oregon Republicans Justices of the Oregon Supreme Court U.S. state supreme court judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law American prosecutors People from Keizer, Oregon Lawyers from Salem, Oregon Stanford University alumni Willamette University alumni Deans of Willamette University College of Law Deaths from brain cancer in the United States Deaths from cancer in Florida Burials in Oregon

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

for public employees. Unions supported McNary throughout his political career.

Several criminal convictions resulted from the Portland vice scandal The Portland vice scandal (sometimes called the vice clique scandal, the vice crusade in contemporary reports, or inaccurately the YMCA scandal) refers to the discovery in November 1912 of a gay male subculture in the U.S. city of Portland, Oregon. ...

in November 1912 surrounding the city's gay male subculture. By the time McNary was seated, some convictions had been appealed to the court. He wrote the dissenting opinion in the reversal of the conviction of prominent Portland attorney Edward McAllister. The dissent was emotionally charged and "revealed a deeply seated personal discomfort with same-sex eroticism".

In 1914, the court moved into the new Oregon Supreme Court Building

The Oregon Supreme Court Building is the home to the Oregon Supreme Court, Oregon Court of Appeals, and the Oregon Judicial Department. Located in the state capitol complex in Salem, it is Oregon's oldest state government building. The three story ...

, and McNary filed to run for a full six-year term on the bench. At that time the office was partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

, and McNary lost the Republican primary, by a single vote, to Henry L. Benson, after several recounts and the discovery of uncounted ballots. After his defeat, he served the remainder of his partial term and left the court in 1915. On July 8, 1916, after a close, multiballot contest, with several contenders, the Republican State Committee elected McNary to be the chair.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', p. 30. He was seen as someone who could unify the progressive and conservative wings of the party in Oregon.

Federal politics

As chairman of the state's Republican Party, McNary campaigned to get the Republican presidential nominee,Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, elected in the 1916 presidential election.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 29–38. Hughes, a former US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

justice and future chief justice, carried Oregon but lost the presidency to the incumbent, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. When US Senator Harry Lane

Harry Lane (August 28, 1855 – May 23, 1917) was an American politician in the state of Oregon. A physician by training, Lane served as the head of the Oregon State Insane Asylum before being forced out by political enemies. After a decade prac ...

died in office, on May 23, 1917, it created an opportunity for McNary to redeem himself after his failed bid for election to the Oregon Supreme Court. McNary was among several possible successors considered by Oregon Governor James Withycombe

James Withycombe (March 21, 1854 – March 3, 1919) was an English-American Republican politician who served as the 15th Governor of Oregon.

Biography

Withycombe was born to tenant farmers Thomas and Mary Ann Withycombe in Tavistock, England, ...

. The governor preferred someone who supported national women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

and Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

, and he shared with McNary an interest in farming.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 32–33 Furthermore, McNary supporters argued that both progressive and conservative factions of the Republican Party would accept McNary and that unity would give the party the best chance of retaining the Senate seat in the next election. Withycombe appointed McNary to the unexpired term on May 29.

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives

The Oregon House of Representatives is the lower house of the Oregon Legislative Assembly. There are 60 members of the House, representing 60 districts across the state, each with a population of 65,000. The House meets in the west wing of the ...

Robert N. Stanfield

Robert Nelson Stanfield Jr (July 9, 1877April 13, 1945) was an American Republican politician and rancher from the state of Oregon who served in the Oregon House of Representatives (1912–18) including as Speaker (1917–18) and was later ele ...

in the May 1918 Republican primary.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 39–50. McNary defeated Stanfield 52,546 to 30,999. In the November general election, he defeated a friend and former governor, Oswald West

Oswald West (May 20, 1873 – August 22, 1960) was an American politician, a Democrat, who served most notably as the 14th Governor of Oregon.

He was called "Os West" by Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook, who described him as "by all odds the mo ...

, 82,360 to 64,303, to win a full, six-year term in the Senate. Meanwhile, Frederick W. Mulkey won the election to replace McNary and finished Lane's original term, which would end in January 1919, and Mulkey took office on November 6, 1918, replacing McNary in that seat.

Shortly after taking office, Mulkey resigned the seat effective December 17, 1918, and McNary was then reappointed to the Senate on December 12, 1918, and took office on December 18, instead of taking office in January, when his term he was elected to would have started. Mulkey resigned in order to give McNary a slight seniority edge over other new members of the Senate. In 1920, former adversary Stanfield defeated incumbent Democrat George Earle Chamberlain

George Earle Chamberlain Sr. (January 1, 1854 – July 9, 1928) was an American attorney, politician, and public official in Oregon. A native of Mississippi and member of the Democratic Party, Chamberlain's political achievements included appoin ...

for Oregon's other Senate seat, making McNary the state's senior senator.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', p. 61–70. McNary won re-election four times, in 1924, 1930, 1936, and 1942, serving in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, until his death.

Senate years

AfterWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Wilson sought Senate approval of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Because the treaty included provisions for establishing and joining the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, one of Wilson's Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

, Republicans opposed it.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 50–59. Going against much of his party, McNary, part of a group of senators known as "reservationists", proposed minor changes to support the United States entry into the League. Ultimately, the Senate never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, and the United States never joined the League.

One of the prime opponents of Wilson and the League was Senate Majority Leader Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

. After McNary demonstrated his skill in the debate over the League, Lodge took him under his wing, and the two formed a longtime friendship. The friendship helped McNary secure favorable committee assignments and ushered him into the inner power circle of the Senate. Early in his career, he served as chairman of the Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands Committee, and as a member of the Agriculture and Forestry Committee. In 1922, President Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

asked McNary to be the Secretary of the Interior to replace Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall (November 26, 1861November 30, 1944) was a United States senator from New Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, infamous for his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal; he was the only pers ...

because of Fall's involvement in the ongoing Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomin ...

. McNary declined, preferring to stay in the Senate.

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans, while the Senate was under Democratic control during the

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans, while the Senate was under Democratic control during the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

era. He remained Minority Leader for the rest of his time in office and "hovered most of the time on the periphery of the Republican left" and opposed disciplining Republican senators who supported Roosevelt. He supported many of the New Deal programs, at the beginning of Roosevelt's presidency. As World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

approached, he favored "all aid to England and France short of war". He voted to keep an arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to "dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintain ...

in place but supported the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

agreement with the British in 1941 and the reinstatement of Selective Service

The Selective Service System (SSS) is an independent agency of the United States government that maintains information on U.S. citizens and other U.S. residents potentially subject to military conscription (i.e., the draft) and carries out contin ...

in 1940, in preparation for military conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

of civilian men.

As early as the 1920s, McNary supported the development of federal hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

dams, and in 1933, he introduced legislation that led to the building of the Grand Coulee

Grand Coulee is an ancient river bed in the U.S. state of Washington. This National Natural Landmark stretches for about 60 miles (100 km) southwest from Grand Coulee Dam to Soap Lake, being bisected by Dry Falls into the Upper and Lower ...

and Bonneville dams on the Columbia, as public works projects. He voted for the US joining the World Court

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

in 1926. He favored buying more National Forest lands, forest management via the McSweeney-McNary Act, fire protection for forests via the Clarke–McNary Act

The Clarke–McNary Act of 1924 (ch. 348, , enacted June 7, 1924) was one of several pieces of United States federal legislation and was named for Representative John D. Clarke and Senator Charles McNary.

The 1911 Weeks Act had allowed the purch ...

, and farm support. Although vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

, the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill

The McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Act, which never became law, was a controversial plan in the 1920s to subsidize American agriculture by raising the domestic prices of five crops. The plan was for the government to buy each crop and then store it o ...

was the forerunner of the farm legislation of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

.

Vice presidential nomination

In 1940, he was the Republican nominee forvice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

, as a western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

farm leader chosen to balance the ticket of presidential nominee Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

, a pro-business leader from the east.

The two men differed on many issues. Writing for ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine shortly before the general election in 1940, Richard L. Neuberger

Richard Lewis Neuberger (December 26, 1912March 9, 1960) was an American journalist, author, and politician during the middle of the 20th century. A native of Oregon, he wrote for ''The New York Times'' before and after a stint in the U.S. Army d ...

said, "Whether as Vice President of the U.S. Charley McNary can keep on endorsing Government-power projects, isolation, high tariffs and huge outlays for farm relief under a President who believes in none of these things remains to be seen." McNary's acceptance speech reiterated his support for the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

, a federally owned power-producing corporation that Willkie, as "the head of a far-flung rivateutilities empire", had opposed. During the campaign, McNary promoted farming issues and criticized foreign trade agreements, which, he said, had "closed European markets to our grain, meat, fruits and fiber". The Willkie/McNary ticket lost decisively to the Roosevelt/Wallace ticket.

Family and legacy

On December 29, 1923, McNary married for the second time, to Cornelia Woodburn Morton. He met Morton at a dinner party duringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, in her hometown of Washington, D.C.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 85–88. Before the marriage, she had worked as his private secretary. As with his first marriage, his second did not produce children, but Charles and Cornelia adopted a daughter, Charlotte, in 1935.

arboretum

An arboretum (plural: arboreta) in a general sense is a botanical collection composed exclusively of trees of a variety of species. Originally mostly created as a section in a larger garden or park for specimens of mostly non-local species, man ...

, and more than of trees. Fir Cone was described as Oregon's Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

by later Senator Richard L. Neuberger, as it hosted many meetings with politicians from the national stage. The farm included of nut and fruit orchards, through which McNary helped establish the filbert industry in Oregon and on which he developed the Imperial prune

A prune is a dried plum, most commonly from the European plum (''Prunus domestica''). Not all plum species or varieties can be dried into prunes. A prune is the firm-fleshed fruit (plum) of ''Prunus domestica'' varieties that have a high solu ...

.

After complaining of headaches and suffering slurred speech

Dysarthria is a speech sound disorder resulting from neurological injury of the motor component of the motor–speech system and is characterized by poor articulation of phonemes. In other words, it is a condition in which problems effectively ...

beginning in early 1943, McNary went to the Bethesda, Maryland, Naval Hospital on November 8, 1943, where doctors diagnosed a malignant

Malignancy () is the tendency of a medical condition to become progressively worse.

Malignancy is most familiar as a characterization of cancer. A ''malignant'' tumor contrasts with a non-cancerous ''benign'' tumor in that a malignancy is not s ...

brain tumor.Neal, ''McNary of Oregon'', pp. 233–235. They removed it that week, and McNary was released from the hospital on December 2, but the cancer had already spread to other parts of his body. He and his family departed for Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Fort Lauderdale () is a coastal city located in the U.S. state of Florida, north of Miami along the Atlantic Ocean. It is the county seat of and largest city in Broward County with a population of 182,760 at the 2020 census, making it the tenth ...

, to spend the winter. He partly recovered from the surgery, but by February 24, 1944, when he was re-elected as Republican Senate leader, he was comatose. Charles L. McNary died in Fort Lauderdale. He was given a state funeral, during which his body lay in state in the chamber of the Oregon House of Representatives at the Oregon State Capitol

The Oregon State Capitol is the building housing the state legislature and the offices of the governor, secretary of state, and treasurer of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is located in the state capitol, Salem. Constructed from 1936 to 1938 ...

, Salem, and then was buried in Belcrest Memorial Cemetery in Salem. At the time of his death, McNary held the record for longest-serving senator from Oregon — 9,726 days in office. This mark held for nearly 50 years, until broken by Mark O. Hatfield

Mark Odom Hatfield (July 12, 1922 – August 7, 2011) was an American politician and educator from the state of Oregon. A Republican, he served for 30 years as a United States senator from Oregon, and also as chairman of the Senate Appropr ...

in 1993.

McNary's running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint Ticket (election), ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate ...

, Willkie, died eight months later on October 8. It was the first, and to date only time both members of a major-party presidential ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

died during the term for which they sought election. Had they been elected, the Presidential Succession Act of 1886

The United States Presidential Succession Act is a federal statute establishing the presidential line of succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact such a statute:

Congress has e ...

would have been invoked upon Willkie's death, and his Secretary of State would have been sworn in as acting president

An acting president is a person who temporarily fills the role of a country's president when the incumbent president is unavailable (such as by illness or a vacation) or when the post is vacant (such as for death, injury, resignation, dismissal ...

for the remainder of the term ending on January 20, 1945.

Named for him are:

* McNary Dam on the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

*McNary Field

McNary Field (Salem Municipal Airport) is in Marion County, Oregon, United States, two miles southeast of downtown Salem, which owns it. The airport is named for U.S. Senator Charles L. McNary.

McNary Field has had scheduled airline flights, i ...

, in Marion County, Oregon

Marion County is one of the 36 counties in the U.S. state of Oregon. The population was 345,920 at the 2020 census, making it the fifth-most populous county in Oregon. The county seat is Salem, which is also the state capital of Oregon. The ...

*McNary High School

McNary High School is a public high school located in Keizer, Oregon, United States. It is named for Charles L. McNary, a U.S. Senator who was from the Keizer area.

Academics

Although McNary High School is one of eight high schools in the Sal ...

in Keizer, Oregon

Keizer () is a city located in Marion County, Oregon, United States, along the 45th parallel. As of the 2010 United States Census, its population was 36,478. It lies in the Willamette Valley, and is part of the Salem Metropolitan Statistical Ar ...

*McNary Residence Hall at Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a public land-grant, research university in Corvallis, Oregon. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate-degree programs along with a variety of graduate and doctoral degrees. It has the 10th largest engineering co ...

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

*List o ...

References

; Bundled referencesExternal links

Senate Portrait

Letter to McNary from President Hoover

Historic images of Charles McNary

from Salem Public Library *

Supreme Court Justices of Oregon

* , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:McNary, Charles L. 1874 births 1944 deaths Politicians from Salem, Oregon American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from Oregon Republican Party United States senators from Oregon 1940 United States vice-presidential candidates Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Oregon Republican Party chairs Oregon Republicans Justices of the Oregon Supreme Court U.S. state supreme court judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law American prosecutors People from Keizer, Oregon Lawyers from Salem, Oregon Stanford University alumni Willamette University alumni Deans of Willamette University College of Law Deaths from brain cancer in the United States Deaths from cancer in Florida Burials in Oregon