Charles I Of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

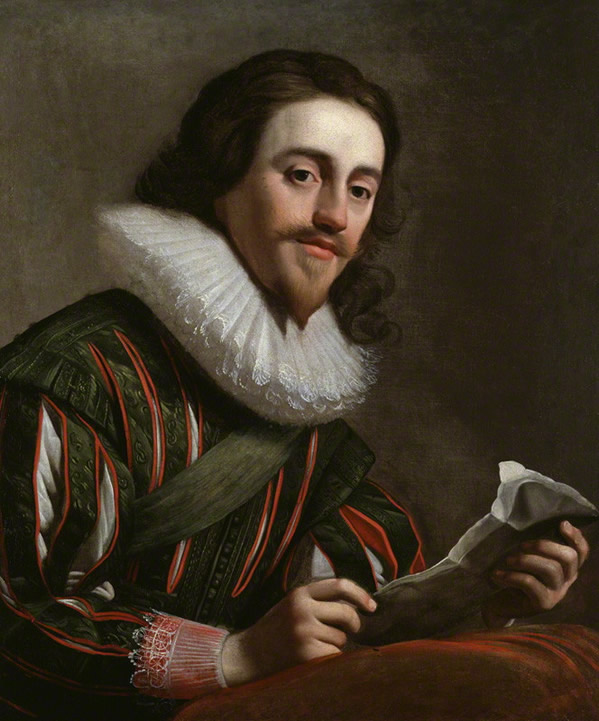

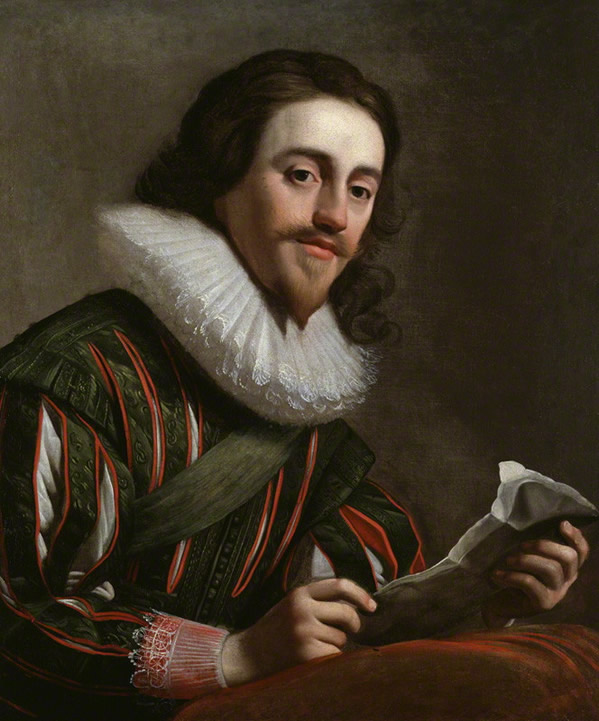

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. He was born into the

In January 1605, Charles was created

In January 1605, Charles was created

Charles and Buckingham, James's

Charles and Buckingham, James's

With the failure of the Spanish match, Charles and Buckingham turned their attention to France. On 1 May 1625 Charles was

With the failure of the Spanish match, Charles and Buckingham turned their attention to France. On 1 May 1625 Charles was  A poorly conceived and executed naval expedition against Spain under Buckingham's leadership went badly, and the House of Commons began proceedings for the impeachment of the duke. In May 1626, Charles nominated Buckingham as Chancellor of Cambridge University in a show of support, and had two members who had spoken against Buckingham

A poorly conceived and executed naval expedition against Spain under Buckingham's leadership went badly, and the House of Commons began proceedings for the impeachment of the duke. In May 1626, Charles nominated Buckingham as Chancellor of Cambridge University in a show of support, and had two members who had spoken against Buckingham

In January 1629, Charles opened the second session of the English Parliament, which had been

In January 1629, Charles opened the second session of the English Parliament, which had been

A large fiscal deficit had arisen during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Notwithstanding Buckingham's short-lived campaigns against both Spain and France, Charles had little financial capacity to wage wars overseas. Throughout his reign, he was obliged to rely primarily on volunteer forces for defence and on diplomatic efforts to support his sister Elizabeth and his foreign policy objective for the restoration of the Palatinate. England was still the least taxed country in Europe, with no official excise and no regular direct taxation. To raise revenue without reconvening Parliament, Charles resurrected an all-but-forgotten law called the "Distraint of Knighthood", in abeyance for over a century, which required any man who earned £40 or more from land each year to present himself at the king's coronation to be knighted. Relying on this old statute, Charles fined those who had failed to attend his coronation in 1626.

The chief tax Charles imposed was a feudal levy known as

A large fiscal deficit had arisen during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Notwithstanding Buckingham's short-lived campaigns against both Spain and France, Charles had little financial capacity to wage wars overseas. Throughout his reign, he was obliged to rely primarily on volunteer forces for defence and on diplomatic efforts to support his sister Elizabeth and his foreign policy objective for the restoration of the Palatinate. England was still the least taxed country in Europe, with no official excise and no regular direct taxation. To raise revenue without reconvening Parliament, Charles resurrected an all-but-forgotten law called the "Distraint of Knighthood", in abeyance for over a century, which required any man who earned £40 or more from land each year to present himself at the king's coronation to be knighted. Relying on this old statute, Charles fined those who had failed to attend his coronation in 1626.

The chief tax Charles imposed was a feudal levy known as

Ireland's population was split into three main sociopolitical groups: the Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Irish, who were Catholic; the Normans in Ireland, Old English, who were descended from Norman invasion of Ireland, medieval Normans and also predominantly Catholic; and the Plantations of Ireland, New English, who were Protestant settlers from England and Scotland aligned with the English Parliament and the Covenanters. Strafford's administration had improved the Irish economy and boosted tax revenue, but had done so by heavy-handedly imposing order. He had trained up a large Catholic army in support of the king and weakened the Irish Parliament's authority, while continuing to confiscate land from Catholics for Protestant settlement at the same time as promoting a Laudian Anglicanism that was anathema to presbyterians. As a result, all three groups had become disaffected. Strafford's impeachment provided a new departure for Irish politics whereby all sides joined together to present evidence against him. In a similar manner to the English Parliament, the Old English members of the Irish Parliament argued that while opposed to Strafford they remained loyal to Charles. They argued that the king had been led astray by malign counsellors, and that, moreover, a viceroy such as Strafford could emerge as a despotic figure instead of ensuring that the king was directly involved in governance.

Strafford's fall from power weakened Charles's influence in Ireland. The dissolution of the Irish army was unsuccessfully demanded three times by the English Commons during Strafford's imprisonment, until lack of money eventually forced Charles to disband the army at the end of Strafford's trial. Disputes over the transfer of land ownership from native Catholic to settler Protestant, particularly in relation to the plantation of Ulster, coupled with resentment at moves to ensure the Irish Parliament was subordinate to the Parliament of England, sowed the seeds of rebellion. When armed conflict arose between the Gaelic Irish and New English in late October 1641, the Old English sided with the Gaelic Irish while simultaneously professing their loyalty to the king.

In November 1641, the House of Commons passed the Grand Remonstrance, a long list of grievances against actions by Charles's ministers committed since the beginning of his reign (that were asserted to be part of a grand Catholic conspiracy of which the king was an unwitting member), but it was in many ways a step too far by Pym and passed by only 11 votes, 159 to 148. Furthermore, the Remonstrance had very little support in the House of Lords, which the Remonstrance attacked. The tension was heightened by news of the Irish rebellion, coupled with inaccurate rumours of Charles's complicity. Throughout November, a series of alarmist pamphlets published stories of atrocities in Ireland, including massacres of New English settlers by the native Irish who could not be controlled by the Old English lords. Rumours of "papist" conspiracies circulated in England, and English anti-Catholic opinion was strengthened, damaging Charles's reputation and authority. The English Parliament distrusted Charles's motivations when he called for funds to put down the Irish rebellion; many members of the Commons suspected that forces he raised might later be used against Parliament itself. Pym's Militia Bill was intended to wrest control of the army from the king, but it did not have the support of the Lords, let alone Charles. Instead, the Commons passed the bill as an ordinance, which they claimed did not require royal assent. The Militia Ordinance appears to have prompted more members of the Lords to support the king. In an attempt to strengthen his position, Charles generated great antipathy in London, which was already fast falling into lawlessness, when he placed the

Ireland's population was split into three main sociopolitical groups: the Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Irish, who were Catholic; the Normans in Ireland, Old English, who were descended from Norman invasion of Ireland, medieval Normans and also predominantly Catholic; and the Plantations of Ireland, New English, who were Protestant settlers from England and Scotland aligned with the English Parliament and the Covenanters. Strafford's administration had improved the Irish economy and boosted tax revenue, but had done so by heavy-handedly imposing order. He had trained up a large Catholic army in support of the king and weakened the Irish Parliament's authority, while continuing to confiscate land from Catholics for Protestant settlement at the same time as promoting a Laudian Anglicanism that was anathema to presbyterians. As a result, all three groups had become disaffected. Strafford's impeachment provided a new departure for Irish politics whereby all sides joined together to present evidence against him. In a similar manner to the English Parliament, the Old English members of the Irish Parliament argued that while opposed to Strafford they remained loyal to Charles. They argued that the king had been led astray by malign counsellors, and that, moreover, a viceroy such as Strafford could emerge as a despotic figure instead of ensuring that the king was directly involved in governance.

Strafford's fall from power weakened Charles's influence in Ireland. The dissolution of the Irish army was unsuccessfully demanded three times by the English Commons during Strafford's imprisonment, until lack of money eventually forced Charles to disband the army at the end of Strafford's trial. Disputes over the transfer of land ownership from native Catholic to settler Protestant, particularly in relation to the plantation of Ulster, coupled with resentment at moves to ensure the Irish Parliament was subordinate to the Parliament of England, sowed the seeds of rebellion. When armed conflict arose between the Gaelic Irish and New English in late October 1641, the Old English sided with the Gaelic Irish while simultaneously professing their loyalty to the king.

In November 1641, the House of Commons passed the Grand Remonstrance, a long list of grievances against actions by Charles's ministers committed since the beginning of his reign (that were asserted to be part of a grand Catholic conspiracy of which the king was an unwitting member), but it was in many ways a step too far by Pym and passed by only 11 votes, 159 to 148. Furthermore, the Remonstrance had very little support in the House of Lords, which the Remonstrance attacked. The tension was heightened by news of the Irish rebellion, coupled with inaccurate rumours of Charles's complicity. Throughout November, a series of alarmist pamphlets published stories of atrocities in Ireland, including massacres of New English settlers by the native Irish who could not be controlled by the Old English lords. Rumours of "papist" conspiracies circulated in England, and English anti-Catholic opinion was strengthened, damaging Charles's reputation and authority. The English Parliament distrusted Charles's motivations when he called for funds to put down the Irish rebellion; many members of the Commons suspected that forces he raised might later be used against Parliament itself. Pym's Militia Bill was intended to wrest control of the army from the king, but it did not have the support of the Lords, let alone Charles. Instead, the Commons passed the bill as an ordinance, which they claimed did not require royal assent. The Militia Ordinance appears to have prompted more members of the Lords to support the king. In an attempt to strengthen his position, Charles generated great antipathy in London, which was already fast falling into lawlessness, when he placed the

In mid-1642, both sides began to arm. Charles raised an army using the medieval method of commission of array, and Parliament called for volunteers for its militia. The negotiations proved futile, and Charles raised the royal standard in Nottingham on 22 August 1642. By then, his forces controlled roughly the Midlands, Wales, the West Country and northern England. He set up his court at Oxford. Parliament controlled London, the south-east and East Anglia, as well as the English navy.

After a few skirmishes, the opposing forces met in earnest at Battle of Edgehill, Edgehill, on 23 October 1642. Charles's nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine disagreed with the battle strategy of the royalist commander Robert Bertie, 1st Earl of Lindsey, Lord Lindsey, and Charles sided with Rupert. Lindsey resigned, leaving Charles to assume overall command assisted by Patrick Ruthven, 1st Earl of Forth, Lord Forth. Rupert's cavalry successfully charged through the parliamentary ranks, but instead of swiftly returning to the field, rode off to plunder the parliamentary baggage train. Lindsey, acting as a colonel, was wounded and bled to death without medical attention. The battle ended inconclusively as the daylight faded.

In his own words, the experience of battle had left Charles "exceedingly and deeply grieved". He regrouped at Oxford, turning down Rupert's suggestion of an immediate attack on London. After a week, he set out for the capital on 3 November, Battle of Brentford (1642), capturing Brentford on the way while simultaneously continuing to negotiate with civic and parliamentary delegations. At Battle of Turnham Green, Turnham Green on the outskirts of London, the royalist army met resistance from the city militia, and faced with a numerically superior force, Charles ordered a retreat. He overwintered in Oxford, strengthening the city's defences and preparing for the next season's campaign. Treaty of Oxford, Peace talks between the two sides collapsed in April.

In mid-1642, both sides began to arm. Charles raised an army using the medieval method of commission of array, and Parliament called for volunteers for its militia. The negotiations proved futile, and Charles raised the royal standard in Nottingham on 22 August 1642. By then, his forces controlled roughly the Midlands, Wales, the West Country and northern England. He set up his court at Oxford. Parliament controlled London, the south-east and East Anglia, as well as the English navy.

After a few skirmishes, the opposing forces met in earnest at Battle of Edgehill, Edgehill, on 23 October 1642. Charles's nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine disagreed with the battle strategy of the royalist commander Robert Bertie, 1st Earl of Lindsey, Lord Lindsey, and Charles sided with Rupert. Lindsey resigned, leaving Charles to assume overall command assisted by Patrick Ruthven, 1st Earl of Forth, Lord Forth. Rupert's cavalry successfully charged through the parliamentary ranks, but instead of swiftly returning to the field, rode off to plunder the parliamentary baggage train. Lindsey, acting as a colonel, was wounded and bled to death without medical attention. The battle ended inconclusively as the daylight faded.

In his own words, the experience of battle had left Charles "exceedingly and deeply grieved". He regrouped at Oxford, turning down Rupert's suggestion of an immediate attack on London. After a week, he set out for the capital on 3 November, Battle of Brentford (1642), capturing Brentford on the way while simultaneously continuing to negotiate with civic and parliamentary delegations. At Battle of Turnham Green, Turnham Green on the outskirts of London, the royalist army met resistance from the city militia, and faced with a numerically superior force, Charles ordered a retreat. He overwintered in Oxford, strengthening the city's defences and preparing for the next season's campaign. Treaty of Oxford, Peace talks between the two sides collapsed in April.

The war continued indecisively over the next couple of years, and Henrietta Maria returned to Britain for 17 months from February 1643. After Rupert Storming of Bristol, captured Bristol in July 1643, Charles visited the port city and laid Siege of Gloucester, siege to Gloucester, further up the river Severn. His plan to undermine the city walls failed due to heavy rain, and on the approach of a parliamentary relief force, Charles lifted the siege and withdrew to Sudeley Castle. The parliamentary army turned back towards London, and Charles set off in pursuit. The two armies met at Newbury, Berkshire, on 20 September. Just as at Edgehill, the First Battle of Newbury, battle stalemated at nightfall, and the armies disengaged. In January 1644, Charles summoned a Parliament at Oxford, which was attended by about 40 peers and 118 members of the Commons; all told, the Oxford Parliament (1644), Oxford Parliament, which sat until March 1645, was supported by the majority of peers and about a third of the Commons. Charles became disillusioned by the assembly's ineffectiveness, calling it a "mongrel" in private letters to his wife.

In 1644, Charles remained in the southern half of England while Rupert rode north to Relief of Newark, relieve Newark and Siege of York, York, which were under threat from parliamentary and Scottish Covenanter armies. Charles was victorious at the battle of Cropredy Bridge in late June, but the royalists in the north were defeated at the battle of Marston Moor just a few days later. The king continued his Battle of Lostwithiel, campaign in the south, encircling and disarming the parliamentary army of the Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, Earl of Essex. Returning northwards to his base at Oxford, he fought at Second Battle of Newbury, Newbury for a second time before the winter closed in; the battle ended indecisively. Attempts to negotiate a settlement over the winter, while both sides rearmed and reorganised, were again unsuccessful.

At the battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645, Rupert's horsemen again mounted a successful charge against the flank of Parliament's

The war continued indecisively over the next couple of years, and Henrietta Maria returned to Britain for 17 months from February 1643. After Rupert Storming of Bristol, captured Bristol in July 1643, Charles visited the port city and laid Siege of Gloucester, siege to Gloucester, further up the river Severn. His plan to undermine the city walls failed due to heavy rain, and on the approach of a parliamentary relief force, Charles lifted the siege and withdrew to Sudeley Castle. The parliamentary army turned back towards London, and Charles set off in pursuit. The two armies met at Newbury, Berkshire, on 20 September. Just as at Edgehill, the First Battle of Newbury, battle stalemated at nightfall, and the armies disengaged. In January 1644, Charles summoned a Parliament at Oxford, which was attended by about 40 peers and 118 members of the Commons; all told, the Oxford Parliament (1644), Oxford Parliament, which sat until March 1645, was supported by the majority of peers and about a third of the Commons. Charles became disillusioned by the assembly's ineffectiveness, calling it a "mongrel" in private letters to his wife.

In 1644, Charles remained in the southern half of England while Rupert rode north to Relief of Newark, relieve Newark and Siege of York, York, which were under threat from parliamentary and Scottish Covenanter armies. Charles was victorious at the battle of Cropredy Bridge in late June, but the royalists in the north were defeated at the battle of Marston Moor just a few days later. The king continued his Battle of Lostwithiel, campaign in the south, encircling and disarming the parliamentary army of the Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, Earl of Essex. Returning northwards to his base at Oxford, he fought at Second Battle of Newbury, Newbury for a second time before the winter closed in; the battle ended indecisively. Attempts to negotiate a settlement over the winter, while both sides rearmed and reorganised, were again unsuccessful.

At the battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645, Rupert's horsemen again mounted a successful charge against the flank of Parliament's

Parliament held Charles under house arrest at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire until Cornet George Joyce took him by threat of force from Holdenby on 3 June in the name of the New Model Army. By this time, mutual suspicion had developed between Parliament, which favoured army disbandment and presbyterianism, and the New Model Army, which was primarily officered by congregationalist polity, congregationalist Independent (religion), Independents, who sought a greater political role. Charles was eager to exploit the widening divisions, and apparently viewed Joyce's actions as an opportunity rather than a threat. He was taken first to Newmarket, Suffolk, Newmarket, at his own suggestion, and then transferred to Oatlands Palace, Oatlands and subsequently Hampton Court Palace, Hampton Court, while more Heads of Proposals, fruitless negotiations took place. By November, he determined that it would be in his best interests to escape—perhaps to France, Southern England or Berwick-upon-Tweed, near the Scottish border. He fled Hampton Court on 11 November, and from the shores of Southampton Water made contact with Colonel Robert Hammond (English army officer), Robert Hammond, Parliamentary Governor of the

Parliament held Charles under house arrest at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire until Cornet George Joyce took him by threat of force from Holdenby on 3 June in the name of the New Model Army. By this time, mutual suspicion had developed between Parliament, which favoured army disbandment and presbyterianism, and the New Model Army, which was primarily officered by congregationalist polity, congregationalist Independent (religion), Independents, who sought a greater political role. Charles was eager to exploit the widening divisions, and apparently viewed Joyce's actions as an opportunity rather than a threat. He was taken first to Newmarket, Suffolk, Newmarket, at his own suggestion, and then transferred to Oatlands Palace, Oatlands and subsequently Hampton Court Palace, Hampton Court, while more Heads of Proposals, fruitless negotiations took place. By November, he determined that it would be in his best interests to escape—perhaps to France, Southern England or Berwick-upon-Tweed, near the Scottish border. He fled Hampton Court on 11 November, and from the shores of Southampton Water made contact with Colonel Robert Hammond (English army officer), Robert Hammond, Parliamentary Governor of the

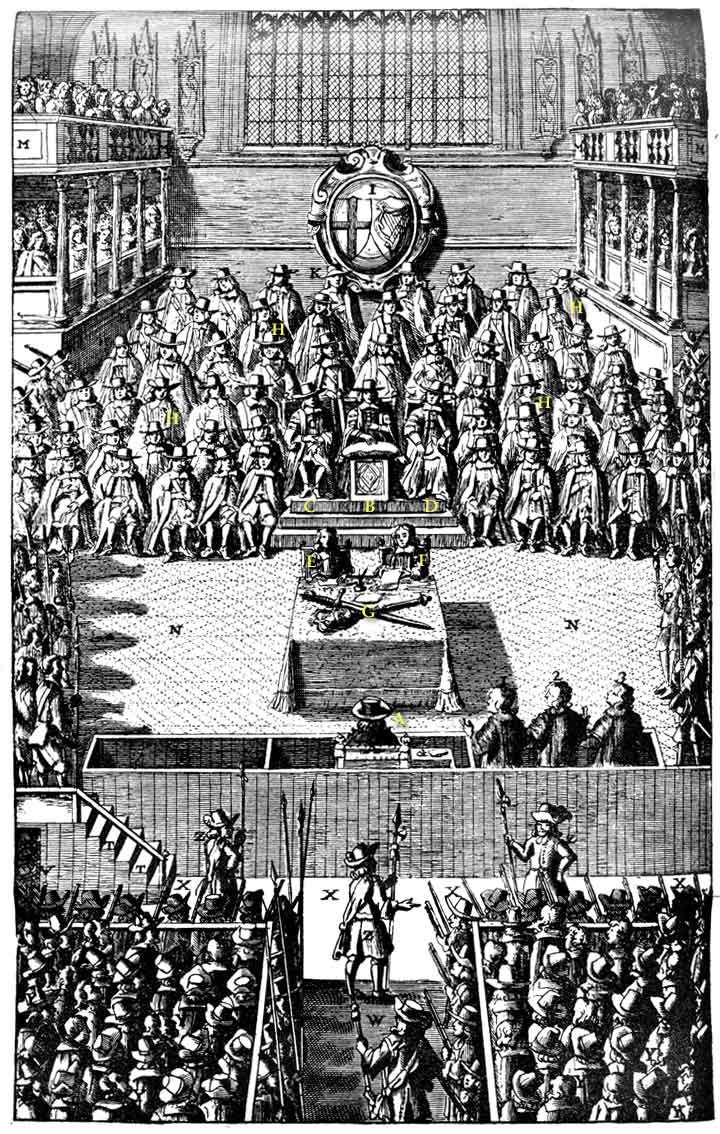

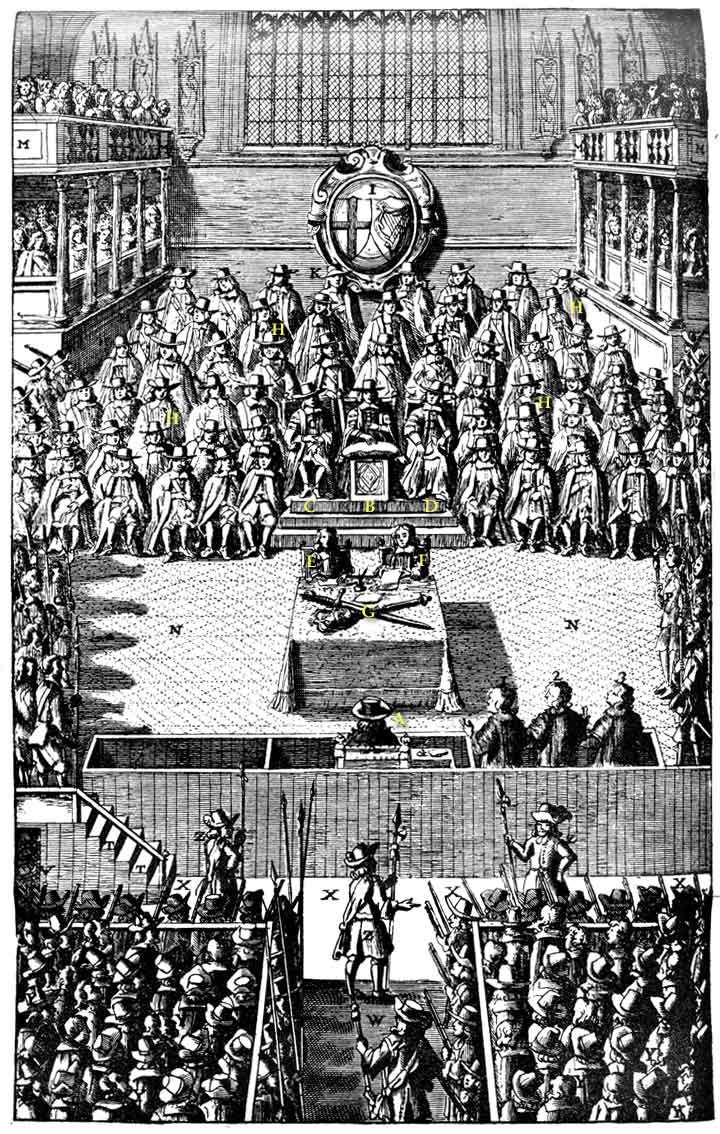

Charles was moved to Hurst Castle at the end of 1648, and thereafter to Windsor Castle. In January 1649, the Rump House of Commons indicted him for treason; the House of Lords rejected the charge. The idea of trying a king was novel. The Chief Justices of the three common law courts of England—Henry Rolle, Oliver St John and John Wilde (jurist), John Wilde—all opposed the indictment as unlawful. The Rump Commons declared itself capable of legislating alone, passed a bill creating a separate court for Charles's trial, and declared the bill an act without the need for royal assent. The High Court of Justice established by the Act consisted of 135 commissioners, but many either refused to serve or chose to stay away. Only 68 (all firm Parliamentarians) attended Charles's trial on charges of high treason and "other high crimes" that began on 20 January 1649 in Palace of Westminster#Westminster Hall, Westminster Hall. John Bradshaw (judge), John Bradshaw acted as President of the Court, and the prosecutor, prosecution was led by Solicitor General for England and Wales, Solicitor General John Cook (regicide), John Cook.

Charles was moved to Hurst Castle at the end of 1648, and thereafter to Windsor Castle. In January 1649, the Rump House of Commons indicted him for treason; the House of Lords rejected the charge. The idea of trying a king was novel. The Chief Justices of the three common law courts of England—Henry Rolle, Oliver St John and John Wilde (jurist), John Wilde—all opposed the indictment as unlawful. The Rump Commons declared itself capable of legislating alone, passed a bill creating a separate court for Charles's trial, and declared the bill an act without the need for royal assent. The High Court of Justice established by the Act consisted of 135 commissioners, but many either refused to serve or chose to stay away. Only 68 (all firm Parliamentarians) attended Charles's trial on charges of high treason and "other high crimes" that began on 20 January 1649 in Palace of Westminster#Westminster Hall, Westminster Hall. John Bradshaw (judge), John Bradshaw acted as President of the Court, and the prosecutor, prosecution was led by Solicitor General for England and Wales, Solicitor General John Cook (regicide), John Cook.

Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of the country. The charge stated that he, "for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented", and that the "wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation." Presaging the modern concept of command responsibility, the indictment held him "guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby." An estimated 300,000 people, or 6% of the population, died during the war.

Over the first three days of the trial, whenever Charles was asked to plead, he refused, stating his objection with the words: "I would know by what power I am called hither, by what lawful authority...?" He claimed that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch, that his own authority to rule had been Divine right of kings, given to him by God and by the traditional laws of England, and that the power wielded by those trying him was only that of force of arms. Charles insisted that the trial was illegal, explaining that, The court, by contrast, challenged the doctrine of sovereign immunity and proposed that "the King of England was not a person, but an office whose every occupant was entrusted with a limited power to govern 'by and according to the laws of the land and not otherwise'."

At the end of the third day, Charles was removed from the court, which then heard over 30 witnesses against him in his absence over the next two days, and on 26 January condemned him to death. The next day, the king was brought before a public session of the commission, declared guilty, and sentenced. List of regicides of Charles I, Fifty-nine of the commissioners signed Charles's death warrant.

Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of the country. The charge stated that he, "for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented", and that the "wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation." Presaging the modern concept of command responsibility, the indictment held him "guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby." An estimated 300,000 people, or 6% of the population, died during the war.

Over the first three days of the trial, whenever Charles was asked to plead, he refused, stating his objection with the words: "I would know by what power I am called hither, by what lawful authority...?" He claimed that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch, that his own authority to rule had been Divine right of kings, given to him by God and by the traditional laws of England, and that the power wielded by those trying him was only that of force of arms. Charles insisted that the trial was illegal, explaining that, The court, by contrast, challenged the doctrine of sovereign immunity and proposed that "the King of England was not a person, but an office whose every occupant was entrusted with a limited power to govern 'by and according to the laws of the land and not otherwise'."

At the end of the third day, Charles was removed from the court, which then heard over 30 witnesses against him in his absence over the next two days, and on 26 January condemned him to death. The next day, the king was brought before a public session of the commission, declared guilty, and sentenced. List of regicides of Charles I, Fifty-nine of the commissioners signed Charles's death warrant.

Charles's execution was scheduled for Tuesday, 30 January 1649. Two of his children remained in England under the control of the Parliamentarians: Elizabeth Stuart (1635–1650), Elizabeth and Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester, Henry. They were permitted to visit him on 29 January, and he bade them a tearful farewell. The next morning, he called for two shirts to prevent the cold weather causing any noticeable shivers that the crowd could have mistaken for fear:. "the season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear. I would have no such imputation."

He walked under guard from St James's Palace, where he had been confined, to the Palace of Whitehall, where an execution scaffold had been erected in front of the Banqueting House, Whitehall, Banqueting House. Charles was separated from spectators by large ranks of soldiers, and his last speech reached only those with him on the scaffold. He blamed his fate on his failure to prevent the execution of his loyal servant Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, Strafford: "An unjust sentence that I suffered to take effect, is punished now by an unjust sentence on me." He declared that he had desired the liberty and freedom of the people as much as any, "but I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consists in having government ... It is not their having a share in the government; that is nothing appertaining unto them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things." He continued, "I shall go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be."

At about 2:00 p.m., Charles put his head on the block after saying a prayer and signalled the executioner when he was ready by stretching out his hands; he was then beheaded in one clean stroke. According to observer Philip Henry (clergyman), Philip Henry, a moan "as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again" rose from the assembled crowd, some of whom then dipped their handkerchiefs in the king's blood as a memento.

The executioner was masked and disguised, and there is debate over his identity. The commissioners approached Richard Brandon, the common hangman of London, but he refused, at least at first, despite being offered £200. It is possible he relented and undertook the commission after being threatened with death, but others have been named as potential candidates, including George Joyce, William Hewlett (regicide), William Hulet and Hugh Peters. The clean strike, confirmed by an examination of the king's body at Windsor in 1813, suggests that the execution was carried out by an experienced headsman.

It was common practice for the severed head of a traitor to be held up and exhibited to the crowd with the words "Behold the head of a traitor!" Charles's head was exhibited, but those words were not used, possibly because the executioner did not want his voice recognised. On the day after the execution, the king's head was sewn back onto his body, which was then embalmed and placed in a lead coffin.

The commission refused to allow Charles's burial at

Charles's execution was scheduled for Tuesday, 30 January 1649. Two of his children remained in England under the control of the Parliamentarians: Elizabeth Stuart (1635–1650), Elizabeth and Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester, Henry. They were permitted to visit him on 29 January, and he bade them a tearful farewell. The next morning, he called for two shirts to prevent the cold weather causing any noticeable shivers that the crowd could have mistaken for fear:. "the season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear. I would have no such imputation."

He walked under guard from St James's Palace, where he had been confined, to the Palace of Whitehall, where an execution scaffold had been erected in front of the Banqueting House, Whitehall, Banqueting House. Charles was separated from spectators by large ranks of soldiers, and his last speech reached only those with him on the scaffold. He blamed his fate on his failure to prevent the execution of his loyal servant Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, Strafford: "An unjust sentence that I suffered to take effect, is punished now by an unjust sentence on me." He declared that he had desired the liberty and freedom of the people as much as any, "but I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consists in having government ... It is not their having a share in the government; that is nothing appertaining unto them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things." He continued, "I shall go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be."

At about 2:00 p.m., Charles put his head on the block after saying a prayer and signalled the executioner when he was ready by stretching out his hands; he was then beheaded in one clean stroke. According to observer Philip Henry (clergyman), Philip Henry, a moan "as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again" rose from the assembled crowd, some of whom then dipped their handkerchiefs in the king's blood as a memento.

The executioner was masked and disguised, and there is debate over his identity. The commissioners approached Richard Brandon, the common hangman of London, but he refused, at least at first, despite being offered £200. It is possible he relented and undertook the commission after being threatened with death, but others have been named as potential candidates, including George Joyce, William Hewlett (regicide), William Hulet and Hugh Peters. The clean strike, confirmed by an examination of the king's body at Windsor in 1813, suggests that the execution was carried out by an experienced headsman.

It was common practice for the severed head of a traitor to be held up and exhibited to the crowd with the words "Behold the head of a traitor!" Charles's head was exhibited, but those words were not used, possibly because the executioner did not want his voice recognised. On the day after the execution, the king's head was sewn back onto his body, which was then embalmed and placed in a lead coffin.

The commission refused to allow Charles's burial at

Charles had nine children, two of whom eventually succeeded as king, and two of whom died at or shortly after birth.

Charles had nine children, two of whom eventually succeeded as king, and two of whom died at or shortly after birth.

Volume I (1637–1640)Volume II (1640–1642)

* * * * * * * *

online

* *

online

* * *

online

*

in JSTOR

*

Official website of the British monarchy

The Society of King Charles the Martyr (United States)

* * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Charles 01 Of England Charles I of England, 1600 births 1649 deaths 16th-century Scottish peers 17th-century Scottish monarchs 17th-century English monarchs 17th-century Irish monarchs 17th-century English nobility 17th-century Scottish peers Protestant monarchs Anglican saints English pretenders to the French throne Princes of England Princes of Scotland Princes of Wales House of Stuart Dukes of Albany Dukes of Cornwall Dukes of Rothesay Dukes of York Earls of Ross, Stuart, Charles Peers of Scotland created by James VI Peers of England created by James I Knights of the Garter People from Dunfermline People of the English Civil War Monarchs taken prisoner in wartime Executed monarchs Dethroned monarchs Executed British people People executed under the Interregnum (England) for treason against England People executed under the Interregnum (England) by decapitation Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle Publicly executed people Christian royal saints High Stewards of Scotland Heads of government who were later imprisoned Children of James VI and I Sons of kings

House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

as the second son of King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

, but after his father inherited the English throne in 1603, he moved to England, where he spent much of the rest of his life. He became heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1612 upon the death of his elder brother, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (19 February 1594 – 6 November 1612), was the eldest son and heir apparent of James VI and I, King of England and Scotland; and his wife Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuar ...

. An unsuccessful and unpopular attempt to marry him to the Spanish Habsburg

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

princess Maria Anna culminated in an eight-month visit to Spain in 1623 that demonstrated the futility of the marriage negotiation. Two years later, he married the Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

princess Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

.

After his 1625 succession, Charles quarrelled with the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

, which sought to curb his royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

. He believed in the divine right of kings

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, before b ...

, and was determined to govern according to his own conscience. Many of his subjects opposed his policies, in particular the levying of taxes without parliamentary consent, and perceived his actions as those of a tyrannical absolute monarch

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

. His religious policies, coupled with his marriage to a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, generated antipathy and mistrust from Reformed

Reform is beneficial change

Reform may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

*''Reforme'' ("Reforms"), initial name of the ...

religious groups such as the English Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

and Scottish Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

, who thought his views too Catholic. He supported high church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

ecclesiastics and failed to aid continental Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

forces successfully during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

. His attempts to force the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

to adopt high Anglican practices led to the Bishops' Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First and ...

, strengthened the position of the English and Scottish parliaments, and helped precipitate his own downfall.

From 1642, Charles fought the armies of the English and Scottish parliaments in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. After his defeat in 1645 at the hands of the Parliamentarian New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

, he fled north from his base at Oxford. Charles surrendered to a Scottish force and after lengthy negotiations between the English and Scottish parliaments he was handed over to the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

in London. Charles refused to accept his captors' demands for a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, and temporarily escaped captivity in November 1647. Re-imprisoned on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

, he forged an alliance with Scotland, but by the end of 1648, the New Model Army had consolidated its control over England. Charles was tried, convicted, and executed for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

in January 1649. The monarchy was abolished and the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

was established as a republic. The monarchy was restored

''Restored'' is the fourth

studio album by American contemporary Christian music musician Jeremy Camp. It was released on November 16, 2004 by BEC Recordings.

Track listing

Standard release

Enhanced edition

Deluxe gold edition

Standard ...

to Charles's son Charles II in 1660.

Early life

The second son of KingJames VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

and Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

, Charles was born in Dunfermline Palace

Dunfermline Palace is a ruined former Scottish royal palace and important tourist attraction in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. It is currently, along with other buildings of the adjacent Dunfermline Abbey, under the care of Historic Environm ...

, Fife, on 19 November 1600. At a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

ceremony in the Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also applie ...

of Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

in Edinburgh on 23 December 1600, he was baptised by David Lindsay, Bishop of Ross, and created Duke of Albany

Duke of Albany is a peerage title that has occasionally been bestowed on the younger sons in the Scottish and later the British royal family, particularly in the Houses of Stuart and Hanover.

History

The Dukedom of Albany was first granted ...

, the traditional title of the second son of the king of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

, with the subsidiary title

A subsidiary title is a title of authority or title of honour that is held by a royal or noble person but which is not regularly used to identify that person, due to the concurrent holding of a greater title.

United Kingdom

An example in the Unit ...

s of Marquess of Ormond, Earl of Ross

The Earl or Mormaer of Ross was the ruler of the province of Ross in northern Scotland.

Origins and transfers

In the early Middle Ages, Ross was part of the vast earldom of Moray. It seems to have been made a separate earldom in the mid 12th ...

and Lord Ardmannoch.

James VI was the first cousin twice removed of Queen Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

, and when she died childless in March 1603, he became King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

as James I. Charles was a weak and sickly infant, and while his parents and older siblings left for England in April and early June that year, due to his fragile health, he remained in Scotland with his father's friend Lord Fyvie

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage ...

appointed as his guardian.

By 1604, when Charles was three-and-a-half, he was able to walk the length of the great hall at Dunfermline Palace without assistance, and it was decided that he was strong enough to journey to England to be reunited with his family. In mid-July 1604, he left Dunfermline for England, where he was to spend most of the rest of his life. In England, Charles was placed under the charge of Elizabeth, Lady Carey, the wife of courtier Sir Robert Carey, who put him in boots made of Spanish leather and brass to help strengthen his weak ankles. His speech development was also slow, and he had a stammer for the rest of his life.

In January 1605, Charles was created

In January 1605, Charles was created Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

, as is customary in the case of the English sovereign's second son, and made a Knight of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

. Thomas Murray, a presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Scot, was appointed as a tutor. Charles learnt the usual subjects of classics, languages, mathematics and religion. In 1611, he was made a Knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George ...

.

Eventually, Charles apparently conquered his physical infirmity, which might have been caused by rickets

Rickets is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children, and is caused by either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stunted growth, bone pain, large forehead, and trouble sleeping. Complications may ...

. He became an adept horseman and marksman, and took up fencing. Even so, his public profile remained low in contrast to that of his physically stronger and taller elder brother, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (19 February 1594 – 6 November 1612), was the eldest son and heir apparent of James VI and I, King of England and Scotland; and his wife Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuar ...

, whom Charles adored and attempted to emulate. But in early November 1612, Henry died at the age of 18 of what is suspected to have been typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

(or possibly porphyria

Porphyria is a group of liver disorders in which substances called porphyrins build up in the body, negatively affecting the skin or nervous system. The types that affect the nervous system are also known as acute porphyria, as symptoms are ra ...

). Charles, who turned 12 two weeks later, became heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

. As the eldest surviving son of the sovereign, he automatically gained several titles, including Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning British monarch, previously the English monarch. The duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in England and was established by a ro ...

and Duke of Rothesay

Duke of Rothesay ( ; gd, Diùc Baile Bhòid; sco, Duik o Rothesay) is a dynastic title of the heir apparent to the British throne, currently William, Prince of Wales. William's wife Catherine, Princess of Wales, is the current Duchess of R ...

. In November 1616, he was created Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

and Earl of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and a ...

.

Heir apparent

In 1613, Charles's sisterElizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

married Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V (german: link=no, Friedrich; 26 August 1596 – 29 November 1632) was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate both r ...

, and moved to Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

. In 1617, the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, a Catholic, was elected king of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

. The next year, the Bohemians rebelled, defenestrating the Catholic governors. In August 1619, the Bohemian diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

chose as their monarch Frederick V, who led the Protestant Union

The Protestant Union (german: Protestantische Union), also known as the Evangelical Union, Union of Auhausen, German Union or the Protestant Action Party, was a coalition of Protestant German states. It was formed on 14 May 1608 by Frederick IV ...

, while Ferdinand was elected Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

in the imperial election

The election of a Holy Roman Emperor was generally a two-stage process whereby, from at least the 13th century, the King of the Romans was elected by a small body of the greatest princes of the Empire, the prince-electors. This was then followed ...

. Frederick's acceptance of the Bohemian crown in defiance of the emperor marked the beginning of the turmoil that would develop into the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

. The conflict, originally confined to Bohemia, spiralled into a wider European war, which the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

and public quickly grew to see as a polarised continental struggle between Catholics and Protestants. In 1620, Charles's brother-in-law, Frederick V, was defeated at the Battle of White Mountain

), near Prague, Bohemian Confederation(present-day Czech Republic)

, coordinates =

, territory =

, result = Imperial-Spanish victory

, status =

, combatants_header =

, combatant1 = Catholic L ...

near Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

and his hereditary lands in the Electoral Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine of ...

were invaded by a Habsburg force from the Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands (Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a ''pars pro toto'') was the Ha ...

. James, however, had been seeking marriage between Prince Charles and Ferdinand's niece, Infanta Maria Anna of Spain

, house = Habsburg

, father = Philip III of Spain

, mother = Margaret of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Linz, Austria

, burial_place = Imperial Crypt

, ...

, and began to see the Spanish match

The Spanish match was a proposed marriage between Charles I of England, Prince Charles, the son of James I of England, King James I of Great Britain, and Infante, Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, the daughter of Philip III of Spain. Negotiations too ...

as a possible diplomatic means of achieving peace in Europe.

Unfortunately for James, negotiation with Spain proved unpopular with both the public and James's court. The English Parliament was actively hostile towards Spain and Catholicism, and thus, when called by James in 1621, the members hoped for an enforcement of recusancy

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

laws, a naval campaign against Spain, and a Protestant marriage for the Prince of Wales. James's Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, was impeached before the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

for corruption. The impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

was the first since 1459 without the king's official sanction in the form of a bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder or writ of attainder or bill of penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and punishing them, often without a trial. As with attai ...

. The incident set an important precedent as the process of impeachment would later be used against Charles and his supporters the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

, Archbishop William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, and the Earl of Strafford. James insisted that the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

be concerned exclusively with domestic affairs, while the members protested that they had the privilege of free speech within the Commons' walls, demanding war with Spain and a Protestant princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was firs ...

. Like his father, Charles considered discussion of his marriage in the Commons impertinent and an infringement of his father's royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

. In January 1622, James dissolved Parliament, angry at what he perceived as the members' impudence and intransigence.

Charles and Buckingham, James's

Charles and Buckingham, James's favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

and a man who had great influence over the prince, travelled incognito to Spain in February 1623 to try to reach agreement on the long-pending Spanish match. The trip was an embarrassing failure. The ''infanta

''Infante'' (, ; f. ''infanta''), also anglicised as Infant or translated as Prince, is the title and rank given in the Iberian kingdoms of Spain (including the predecessor kingdoms of Aragon, Castile, Navarre, and León) and Portugal to th ...

'' thought Charles little more than an infidel, and the Spanish at first demanded that he convert to Roman Catholicism as a condition of the match. They insisted on toleration of Catholics in England and the repeal of the English penal laws

In English history, the penal laws were a series of laws that sought to uphold the establishment of the Church of England against Catholicism and Protestant nonconformists by imposing various forfeitures, civil penalties, and civil disabilities ...

, which Charles knew Parliament would not agree to, and that the ''infanta'' remain in Spain for a year after any wedding to ensure that England complied with all the treaty's terms. A personal quarrel erupted between Buckingham and the Count of Olivares {{Short description, Family

The House of Olivares is a Spanish noble house originating in the Crown of Castile. It is a cadet branch of the House of Medina Sidonia, originating in the sixteenth century.

Historically, the house possessed the lor ...

, the Spanish chief minister, and so Charles conducted the ultimately futile negotiations personally. When he returned to London in October, without a bride and to a rapturous and relieved public welcome, he and Buckingham pushed the reluctant King James to declare war on Spain.

With the encouragement of his Protestant advisers, James summoned the English Parliament in 1624 to request subsidies for a war. Charles and Buckingham supported the impeachment of the Lord Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

, Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of Middlesex

Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of Middlesex (1575 – 6 August 1645) was an English merchant and politician. He sat in the House of Commons between 1614 and 1622 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Cranfield.

Life

He was the second son ...

, who opposed war on grounds of cost and quickly fell in much the same manner Bacon had. James told Buckingham he was a fool, and presciently warned Charles that he would live to regret the revival of impeachment as a parliamentary tool. An underfunded makeshift army under Ernst von Mansfeld

Peter Ernst, Graf von Mansfeld (german: Peter Ernst Graf von Mansfeld; c. 158029 November 1626), or simply Ernst von Mansfeld, was a German military commander who, despite being a Catholic, fought for the Protestants during the early years of the ...

set off to recover the Palatinate, but it was so poorly provisioned that it never advanced beyond the Dutch coast.

By 1624, the increasingly ill James was finding it difficult to control Parliament. By the time of his death in March 1625, Charles and the Duke of Buckingham had already assumed ''de facto'' control of the kingdom.

Early reign

With the failure of the Spanish match, Charles and Buckingham turned their attention to France. On 1 May 1625 Charles was

With the failure of the Spanish match, Charles and Buckingham turned their attention to France. On 1 May 1625 Charles was married by proxy

A proxy wedding or proxy marriage is a wedding in which one or both of the individuals being united are not physically present, usually being represented instead by other persons. If both partners are absent a double proxy wedding occurs.

Marriage ...

to the 15-year-old French princess Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

in front of the doors of Notre Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

. He had seen her in Paris while en route to Spain. The married couple met in person on 13 June 1625 in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

. Charles delayed the opening of his first Parliament until after the marriage was consummated, to forestall any opposition. Many members of the Commons opposed his marriage to a Roman Catholic, fearing that he would lift restrictions on Catholic recusants and undermine the official establishment of the reformed Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. Charles told Parliament that he would not relax religious restrictions, but promised to do exactly that in a secret marriage treaty with his brother-in-law Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

. Moreover, the treaty loaned to the French seven English naval ships that were used to suppress the Protestant Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss politica ...

at La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

in September 1625. Charles was crowned on 2 February 1626 at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, but without his wife at his side, because she refused to participate in a Protestant religious ceremony.

Distrust of Charles's religious policies increased with his support of a controversial anti-Calvinist ecclesiastic, Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu (or Mountague) (1577 – 13 April 1641) was an English cleric and prelate.

Early life

Montagu was born during Christmastide 1577 at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, where his father Laurence Mountague was vicar, and was educated at Eto ...

, who was in disrepute among the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s. In his pamphlet ''A New Gag for an Old Goose'' (1624), a reply to the Catholic pamphlet ''A New Gag for the New Gospel'', Montagu argued against Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

, the doctrine that God preordained salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and damnation

Damnation (from Latin '' damnatio'') is the concept of divine punishment and torment in an afterlife for actions that were committed, or in some cases, not committed on Earth.

In Ancient Egyptian religious tradition, citizens would recite th ...

. Anti-Calvinistsknown as Arminians

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Rem ...

believed that people could influence their fates by exercising free will. Arminian divines had been one of the few sources of support for Charles's proposed Spanish marriage. With King James's support, Montagu produced another pamphlet, '' Appello Caesarem'', published in 1625 shortly after James's death and Charles's accession. To protect Montagu from the stricture of Puritan members of Parliament, Charles made him a royal chaplain, heightening many Puritans' suspicions that Charles favoured Arminianism as a clandestine attempt to aid Catholicism's resurgence.

Rather than direct involvement in the European land war, the English Parliament preferred a relatively inexpensive naval attack on Spanish colonies in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

, hoping for the capture of the Spanish treasure fleet

The Spanish treasure fleet, or West Indies Fleet ( es, Flota de Indias, also called silver fleet or plate fleet; from the es, label=Spanish, plata meaning "silver"), was a convoy system of sea routes organized by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to ...

s. Parliament voted to grant a subsidy of £140,000, an insufficient sum for Charles's war plans. Moreover, the House of Commons limited its authorisation for royal collection of tonnage and poundage

Tonnage and poundage were duties and taxes first levied in Edward II's reign on every tun (cask) of imported wine, which came mostly from Spain and Portugal, and on every pound weight of merchandise exported or imported. Traditionally tonnage an ...

(two varieties of customs duties) to a year, although previous sovereigns since Henry VI had been granted the right for life. In this manner, Parliament could delay approval of the rates until after a full-scale review of customs revenue. The bill made no progress in the House of Lords past its first reading

A reading of a bill is a stage of debate on the bill held by a general body of a legislature.

In the Westminster system, developed in the United Kingdom, there are generally three readings of a bill as it passes through the stages of becoming, ...

. Although no Parliamentary Act for the levy of tonnage and poundage was obtained, Charles continued to collect the duties.

A poorly conceived and executed naval expedition against Spain under Buckingham's leadership went badly, and the House of Commons began proceedings for the impeachment of the duke. In May 1626, Charles nominated Buckingham as Chancellor of Cambridge University in a show of support, and had two members who had spoken against Buckingham

A poorly conceived and executed naval expedition against Spain under Buckingham's leadership went badly, and the House of Commons began proceedings for the impeachment of the duke. In May 1626, Charles nominated Buckingham as Chancellor of Cambridge University in a show of support, and had two members who had spoken against BuckinghamDudley Digges

Sir Dudley Digges (19 May 1583 – 18 March 1639) was an English diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1610 and 1629. Digges was also a "Virginia adventurer," an investor who ventured his capital in the Virginia ...