Charles Hodge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Hodge (December 27, 1797 – June 19, 1878) was a Reformed

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

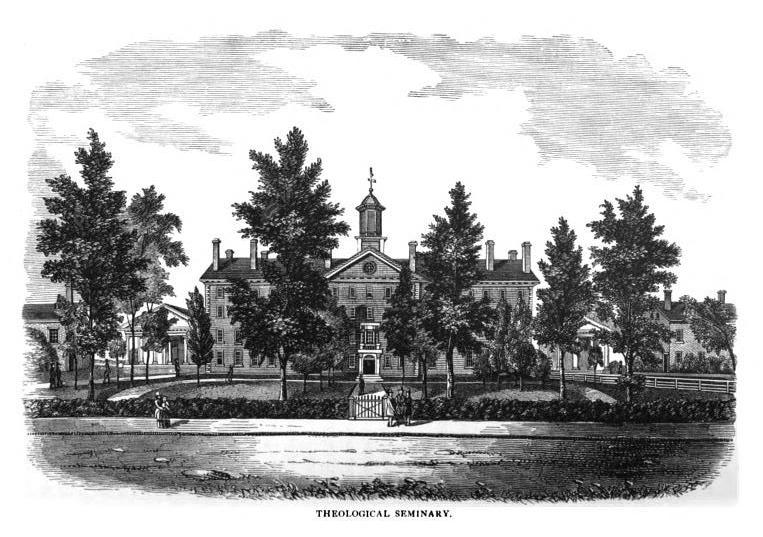

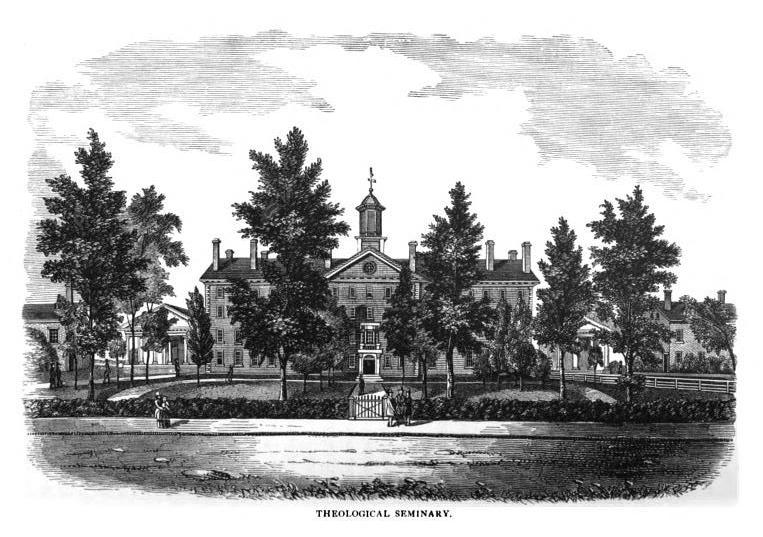

and principal of Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of ...

between 1851 and 1878.

He was a leading exponent of the Princeton Theology, an orthodox Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

theological tradition in America during the 19th century. He argued strongly for the authority of the Bible as the Word of God. Many of his ideas were adopted in the 20th century by Fundamentalists and Evangelicals.

Biography

Charles Hodge's father, Hugh, was the son of aScotsman

The Scots ( sco, Scots Fowk; gd, Albannaich) are an ethnic group and nation native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged in the early Middle Ages from an amalgamation of two Celtic-speaking peoples, the Picts and Gaels, who founded t ...

who emigrated from Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

early in the eighteenth century.

Hugh graduated from Princeton College

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

in 1773 and served as a military surgeon in the Revolutionary War, after which he practiced medicine in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

.

He married well-born Bostonian orphan Mary Blanchard in 1790. The Hodge's first three sons died in the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, 5,000 or more people were listed in the official register of deaths between August 1 and November 9. The vast majority of them died of yellow fever, making the epidemic in the city of 50,000 ...

and another yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

epidemic in 1795. Their first son to survive childhood, Hugh Lenox, was born in 1796. Hugh Lenox would become an authority in obstetrics

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgi ...

, and he would remain especially close with Charles, often assisting him financially. Charles was born on December 27, 1797. His father died seven months later of complications from the yellow fever he had contracted in the epidemic of 1795. They were brought up by relatives, many of whom were wealthy and influential. Mary Hodge made sacrifices and took in boarders in order to put the boys through school. She, with the help of the family's minister Ashbel Green, also provided the customary Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

religious education using the Westminster Shorter Catechism

The Westminster Shorter Catechism is a catechism written in 1646 and 1647 by the Westminster Assembly, a synod of English and Scottish theologians and laymen intended to bring the Church of England into greater conformity with the Church of Sco ...

. They moved to Somerville, New Jersey

Somerville is a borough and the county seat of Somerset County, New Jersey, United States.New Je ...

in 1810 in order to attend a classical academy, and again to Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

in 1812 in order to enter Princeton College, a school originally organized to train Presbyterian ministers. As Charles prepared to enter the college, Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of ...

was being established by the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

as a separate institution for training ministers in response to a perceived inadequacy in the training ministers were receiving at the university as well as the perception that the college was drifting from orthodoxy. Also in 1812, Ashbel Green, the Hodge's old minister, became president of the college.

At Princeton, the first president of the new seminary, Archibald Alexander

Archibald Alexander (April 17, 1772 – October 22, 1851) was an American Presbyterian theologian and professor at the Princeton Theological Seminary. He served for 9 years as the President of Hampden–Sydney College in Virginia and for 39 yea ...

, took a special interest in Hodge, assisting him in Greek and taking him with him on itinerant preaching trips. Hodge would name his first son after Alexander. Hodge became close friends with future Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

bishops John Johns

John Johns (July 10, 1796 – April 5, 1876) was the fourth Episcopal bishop of Virginia. He led his diocese into secession and during the American Civil War and later tried to heal it through the Reconstruction Era. Johns also served as Pres ...

and Charles McIlvaine, and future Princeton College president John Mclean

John McLean (March 11, 1785 – April 4, 1861) was an American jurist and politician who served in the United States Congress, as U.S. Postmaster General, and as a justice of the Ohio and U.S. Supreme Courts. He was often discussed for t ...

. In 1815, during a time of intense religious fervor among the students encouraged by Green and Alexander, Hodge joined the local Presbyterian church and decided to enter the ministry. Shortly after completing his undergraduate studies he entered the seminary in 1816. The course of study was very rigorous, requiring students to recite scripture in the original languages and to use the dogmatics written in Latin in the 17th century by Reformed scholastic Francis Turretin

Francis Turretin (17 October 1623 – 28 September 1687; also known as François Turrettini) was a Genevan-Italian Reformed scholastic theologian.Samuel Miller also inculcated an intense piety in their students.

Following graduation from Princeton Seminary in 1819, Hodge received additional instruction privately from Hebrew scholar Rev. Joseph Bates in Philadelphia. He was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Philadelphia in 1820, and he preached regularly as a missionary in vacant pulpits in the  Starting in the 1830s Hodge suffered from an immobilizing pain in his leg, and was forced to conduct his classes from his study from 1833 to 1836. He continued to write articles for ''Biblical Repertory'', now renamed the ''Princeton Review''. During the 1830s he wrote a major

Starting in the 1830s Hodge suffered from an immobilizing pain in his leg, and was forced to conduct his classes from his study from 1833 to 1836. He continued to write articles for ''Biblical Repertory'', now renamed the ''Princeton Review''. During the 1830s he wrote a major

Systematic Theology

'. Hendrickson Publishers (1999). (also available abridged by Edward N. Gross, ) * ''Romans'' (The Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1994). * ''Romans'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''Corinthians'' (Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1995). * ''1 & 2 Corinthians'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''2 Corinthians'' (Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1995). *

' (The Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1994). * ''Ephesians'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''The Way of Life'' (Sources of American Spirituality). Mark A. Noll, ed. Paulist Press (1987).

Charles Hodge: A voice for today’s PCUSA?

''The Layman''. * Anderson, Robert * Gutjahr Paul C. ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (

The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review

', 1830–82, at the University of Michigan'

"Humanities Text Initiative"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hodge, Charles 1797 births 1878 deaths 19th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians American Calvinist and Reformed theologians American abolitionists American slave owners American evangelicals Burials at Princeton Cemetery New Testament scholars Presbyterian abolitionists Presbyterian Church in the United States ministers Presidents of Calvinist and Reformed seminaries Princeton Theological Seminary alumni Princeton Theological Seminary faculty Princeton University alumni Systematic theologians 19th-century American clergy

East Falls

East Falls (also The Falls, formerly the Falls of Schuylkill) is a neighborhood in the Northwest section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the United States. It lies on the east bank of the "Falls of the Schuylkill," cataracts submerged in 1 ...

neighborhood of Philadelphia, the Frankford Arsenal

The Frankford Arsenal is a former United States Army ammunition plant located adjacent to the Bridesburg neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, north of the original course of Frankford Creek.

History

Opened in 1816 on of land p ...

in Philadelphia, and Woodbury, New Jersey

Woodbury is the county seat of Gloucester County, New Jersey, Gloucester County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is part of the South Jersey region of the state.

over the subsequent months. In 1820 he accepted a one-year appointment as assistant professor at Princeton Seminary to teach biblical languages. In October of that year he traveled throughout New England to speak with professors and ministers including Moses Stuart

Moses B. Stuart (March 26, 1780 – January 4, 1852) was an American biblical scholar.

Life and career

Moses Stuart was born in Wilton, Connecticut on March 26, 1780. He was brought up on a farm, then attended Yale University graduating with hig ...

at Andover Seminary

Andover Newton Theological School (ANTS) was a graduate school and seminary in Newton, Massachusetts. Affiliated with the American Baptist Churches USA and the United Church of Christ. It was the product of a merger between Andover Theological ...

and Nathaniel W. Taylor

Nathaniel William Taylor (June 23, 1786 – March 10, 1858) was an influential Protestant Theologian of the early 19th century, whose major contribution to the Christian faith (and to American religious history), known as the New Haven theology ...

at Yale Divinity School

Yale Divinity School (YDS) is one of the twelve graduate and professional schools of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Congregationalist theological education was the motivation at the founding of Yale, and the professional school has ...

. In 1821 he was ordained a minister by the Presbytery of New Brunswick, and in 1822 he published his first pamphlet, which allowed Alexander to convince the General Assembly to appoint him full Professor of Oriental and Biblical Literature. Financially stable, Hodge married Sarah Bache, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

's great-granddaughter in the same year. In 1824, Hodge helped to found the Chi Phi

Chi Phi () is considered by some as the oldest American men's college social fraternity that was established as the result of the merger of three separate organizations that were each known as Chi Phi. The earliest of these organizations was for ...

Society along with Robert Baird and Archibald Alexander

Archibald Alexander (April 17, 1772 – October 22, 1851) was an American Presbyterian theologian and professor at the Princeton Theological Seminary. He served for 9 years as the President of Hampden–Sydney College in Virginia and for 39 yea ...

. He founded the quarterly '' Biblical Repertory'' in 1825 to translate the current scholarly literature on the Bible from Europe.

Hodge's study of European scholarship led him to question the adequacy of his training. The seminary agreed to continue to pay him for two years while he traveled in Europe to "round out" his education. He supplied a substitute, John Nevin on his own expense. From 1826 to 1828 he traveled to Paris, where he studied French, Arabic, and Syriac; Halle, where he studied German with George Müller

George Müller (born Johann Georg Ferdinand Müller, 27 September 1805 – 10 March 1898) was a Christian evangelist and the director of the Ashley Down orphanage in Bristol, England. He was one of the founders of the Plymouth Brethren m ...

and made the acquaintance of August Tholuck

Friedrich August Gottreu Tholuck (30 March 1799 – 10 June 1877), known as August Tholuck, was a German Protestant theologian, pastor, and historian, and church leader.

Biography

Tholuck was born at Breslau, and educated at the gymnasium and ...

; and Berlin where he attended the lectures of Silvestre de Sacy

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (; 21 September 175821 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Life and works

Early life

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Pa ...

, Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg

Ernst Wilhelm Theodor Herrmann Hengstenberg (20 October 1802, in Fröndenberg28 May 1869, in Berlin), was a German Lutheran churchman and neo-Lutheran theology, theologian from an old and important Dortmund family.

He was born at Fröndenberg, ...

, and August Neander

Johann August Wilhelm Neander (17 January 178914 July 1850) was a German theologian and church historian.

Biography

Neander was born at Göttingen as David Mendel. His father, Emmanuel Mendel, is said to have been a Jewish peddler, but August ...

. There he also became personally acquainted with Friedrich Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional P ...

, the leading modern theologian. He admired the deep scholarship he witnessed in Germany, but thought that the attention given to idealist philosophy clouded common sense, and led to speculative and subjective theology. Unlike other American theologians who spent time in Europe, Hodge's experience did not cause any change in his commitment to the principles of the faith he had learned from childhood.

Starting in the 1830s Hodge suffered from an immobilizing pain in his leg, and was forced to conduct his classes from his study from 1833 to 1836. He continued to write articles for ''Biblical Repertory'', now renamed the ''Princeton Review''. During the 1830s he wrote a major

Starting in the 1830s Hodge suffered from an immobilizing pain in his leg, and was forced to conduct his classes from his study from 1833 to 1836. He continued to write articles for ''Biblical Repertory'', now renamed the ''Princeton Review''. During the 1830s he wrote a major commentary

Commentary or commentaries may refer to:

Publications

* ''Commentary'' (magazine), a U.S. public affairs journal, founded in 1945 and formerly published by the American Jewish Committee

* Caesar's Commentaries (disambiguation), a number of works ...

on Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and a history of the Presbyterian church in America. He supported the Old School in the Old School–New School Controversy

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

* Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, ...

, which resulted in a split in 1837. In 1840 he became Professor of Didactic Theology, retaining, however, the department of New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

exegesis, the duties of which he continued to discharge until his death. He was moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (Old School) in 1846. Hodge's wife died in 1849, shortly followed by Samuel Miller and Archibald Alexander, leaving him the senior professor of the seminary. He was recognized as the leading proponent of the Princeton theology. On his death in 1878 he was recognized by both friends and opponents as one of the greatest polemicists of his time. Of his children who survived him, three were ministers; and two of these succeeded him in the faculty of Princeton Theological Seminary, C. W. Hodge, in the department of exegetical theology, and A. A. Hodge, in that of dogmatics. A grandson, C. W. Hodge, Jr., also taught for many years at Princeton Seminary.

Literary and teaching activities

Hodge wrote many biblical and theological works. He began writing early in his theological career and continued publishing until his death. In 1835 he published his ''Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans''. Although considered to be his greatest exegetical work, Hodge revised this commentary in 1864, in the midst of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, and after a debate with James Henley Thornwell

James Henley Thornwell (December 9, 1812 – August 1, 1862) was an American Presbyterian preacher, slaveowner, and religious writer from the U.S. state of South Carolina during the 19th century. During the American Civil War, Thornwell support ...

about state secession from the Union.

Other works followed at intervals of longer or shorter duration – ''Constitutional History of the Presbyterian Church in the United States'' (1840); ''Way of Life'' (1841, republished in England, translated into other languages, and circulated to the extent of 35,000 copies in America); ''Commentary on Ephesians'' (1856); ''on First Corinthians'' (1857); ''on Second Corinthians'' (1859). His ''magnum opus'' is the ''Systematic Theology'' (1871–1873), of 3 volumes and extending to 2,260 pages. His last book, ''What is Darwinism?'' appeared in 1874. In addition to all this it must be remembered that he contributed upward of 130 articles to the ''Princeton Review'', many of which, besides exerting a powerful influence at the time of their publication, have since been gathered into volumes, and as Selection of ''Essays and Reviews from the Princeton Review'' (1857) and ''Discussions in Church Polity'' (ed. W. Durant, 1878) have taken a permanent place in theological literature.

This record of Hodge's literary life is suggestive of the great influence that he exerted. But properly to estimate that influence, it must be remembered that 3,000 ministers of the Gospel passed under his instruction, and that to him was accorded the rare privilege, during the course of a long life, of achieving distinction as a teacher, exegete, preacher, controversialist, ecclesiastic, and systematic theologian. As a teacher he had few equals; and if he did not display popular gifts in the pulpit, he revealed homiletic powers of a high order in the "conferences" on Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, commanded by God to be kept as a holy day of rest, as G ...

afternoons, where he spoke with his accustomed clearness and logical precision, but with great spontaneity and amazing tenderness and unction.

Hodge's literary powers were seen at their best in his contributions to the '' Princeton Theological Review'', many of which are acknowledged masterpieces of controversial writing. They cover a wide range of topics, from apologetic

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

questions that concern common Christianity to questions of ecclesiastical administration, in which only Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

s have been supposed to take interest. But the questions in debate among American theologians during the period covered by Hodge's life belonged, for the most part, to the departments of anthropology and soteriology

Soteriology (; el, σωτηρία ' "salvation" from σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many religio ...

; and it was upon these, accordingly, that his polemic powers were mainly applied.

All of the books that he authored have remained in print over a century after his death.

Character and significance

Devotion to Christ was the salient characteristic of his experience, and it was the test by which he judged the experience of others. Hence, though a Presbyterian and a Calvinist, his sympathies went far beyond the boundaries of sect. He refused to entertain the narrow views of church polity which some of his brethren advocated. He repudiated the unhistorical position of those who denied the validity of Roman Catholic baptism. He was conservative by nature, and his life was spent in defending the Reformed theology as set forth in theWestminster Confession of Faith

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith. Drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly as part of the Westminster Standards to be a confession of the Church of England, it became and remains the " subordinate standard" ...

and Larger and Westminster Shorter Catechism

The Westminster Shorter Catechism is a catechism written in 1646 and 1647 by the Westminster Assembly, a synod of English and Scottish theologians and laymen intended to bring the Church of England into greater conformity with the Church of Sco ...

s. He was fond of saying that Princeton had never originated a new idea; but this meant no more than that Princeton was the advocate of historical Calvinism in opposition to the modified and provincial Calvinism of a later day. And it is true that Hodge must be classed among the great defenders of the faith, rather than among the great constructive minds of the Church. He had no ambition to be epoch-making by marking the era of a new departure. But he earned a higher title to fame in that he was the champion of his Church's faith during a long and active life, her trusted leader in time of trial, and for more than half a century the most conspicuous teacher of her ministry. Hodges' understanding of the Christian faith and of historical Protestantism is given in his ''Systematic Theology.''

Views on controversial topics

Slavery

As an archconservative and a believer in both the inerrancy and the literal interpretation of the Bible, Hodge supported the institution ofslavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in its most abstract sense, as having support from certain passages in the Bible. He held slaves himself, but he condemned their mistreatment, and made a distinction between slavery in the abstract and what he saw as the unjust Southern Slave Laws that deprived slaves of their right to educational instruction, to marital and parental rights, and that "subject them to the insults and oppression of the whites." It was his opinion that the humanitarian reform of these laws would become the necessary prelude to the eventual end of slavery in the United States. See Pages 6 and 77.

The Presbyterian General Assembly of 1818 had affirmed a similar position, that slavery within the United States, while not necessarily sinful, was a regrettable institution that ought to eventually be changed. Like the church, Hodge himself had sympathies with both the abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

in the North and the pro-slavery advocates in the South, and he used his considerable influence in an attempt to restore order and find common ground between the two factions, with the eventual hope of abolishing slavery altogether.

Hodge's support of slavery was not an inevitable result of his belief in the inerrancy and the literal interpretation of the Bible. Other 19th century Christian contemporaries of Hodge, who also believed in the inerrancy and infallibility of the Bible, denounced the institution of slavery. John Williamson Nevin

John Williamson Nevin (February 20, 1803June 6, 1886), was an American theologian and educationalist. He was born in the Cumberland Valley, near Shippensburg, Franklin County, Pennsylvania. He was the father of noted sculptor and poet Blanche Nev ...

, a conservative, evangelical Reformed scholar and seminary professor, denounced slavery as 'a vast moral evil.' Hodge and Nevin also famously clashed over polar-opposite views of the Lord's Supper.

Old School

Hodge was a leader of the Old School faction of Presbyterians during the division of thePresbyterian Church (USA)

The Presbyterian Church (USA), abbreviated PC(USA), is a mainline Protestant denomination in the United States. It is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the US, and known for its liberal stance on doctrine and its ordaining of women and ...

in 1837. The issues involved conflicts over doctrine, religious practice, and slavery. Although prior to 1861 the Old School refrained from denouncing slavery, the issue was a matter of debate between Northern and Southern components of the denomination.

Civil War

Hodge could tolerate slavery but he could never tolerate treason of the sort he saw trying to break up the United States in 1861. Hodge was a strong nationalist and led the fight among Presbyterians to support the Union. In the January 1861 ''Princeton Review'', Hodge laid out his case against secession, in the end calling it unconstitutional.James Henley Thornwell

James Henley Thornwell (December 9, 1812 – August 1, 1862) was an American Presbyterian preacher, slaveowner, and religious writer from the U.S. state of South Carolina during the 19th century. During the American Civil War, Thornwell support ...

responded in the January 1861 ''Southern Presbyterian Review,'' holding that the election of 1860 had installed a new government, one which the South did not agree with, thus making secession lawful. Despite being a staunch Unionist politically, Hodge voted against the support for the "Spring Resolutions" of the 1861 General Assembly of the Old School Presbyterian Church, thinking it was not the business of the church to involve itself in political matters; because of the resolutions, the denomination then split North and South. When the General Assembly convened in Philadelphia in May 1861, one month after the Civil War began, the resolution stipulated pledging support for the federal government over objections based on concerns about the scope of church jurisdiction and disagreements about its interpretation of the Constitution. In December 1861, the Southern Old School Presbyterian churches severed ties with the denomination.

Darwinism

In 1874, Hodge published ''What is Darwinism?'', claiming thatDarwinism

Darwinism is a scientific theory, theory of Biology, biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of smal ...

, was, in essence, atheism. To Hodge, Darwinism was contrary to the notion of design and was therefore clearly atheistic. Both in the ''Review'' and in ''What is Darwinism?,'' (1874) Hodge attacked Darwinism. His views determined the position of the Seminary until his death in 1878. While he didn't consider all evolutionary ideas to be in conflict with his religion, he was concerned with its teaching in colleges. Meanwhile, at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, a totally separate institution, President John Maclean also rejected Darwin's theory of evolution. However, in 1868, upon Maclean's retirement, James McCosh

James McCosh (April 1, 1811 – November 16, 1894) was a philosopher of the Scottish School of Common Sense. He was president of Princeton University 1868–88.

Biography

McCosh was born into a Covenanting family in Ayrshire, and ...

, a Scottish philosopher, became president. McCosh believed that much of Darwinism could and would be proved sound, and so he strove to prepare Christians for this event. Instead of conflict between science and religion, McCosh sought reconciliation. Insisting on the principle of design in nature, McCosh interpreted the Darwinian discoveries as more evidence of the prearrangement, skill, and purpose in the universe. He thus argued that Darwinism was not atheistic nor in irreconcilable hostility to the Bible. The Presbyterians in America thus could choose between two schools of thought on evolution, both based in Princeton. The Seminary held to Hodge's position until his supporters were ousted in 1929, and the college (Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

) became a world class center of the new science of evolutionary biology.

The debate between Hodge and McCosh exemplified an emerging conflict between science and religion over the question of Darwin's evolution theory. However, the two men showed greater similarities regarding matters of science and religion than popularly appreciated. Both supported the increasing role of scientific inquiry in natural history and resisted its intrusion into philosophy and religion.

Works

Books

* * * * - There is an 1860 reprint available through MOA http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moa/AJH0374.0001.001/1 (not in the public domain) * * * * * *Journals

* *Sermons

*Articles

* * *Modern reprints

*Systematic Theology

'. Hendrickson Publishers (1999). (also available abridged by Edward N. Gross, ) * ''Romans'' (The Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1994). * ''Romans'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''Corinthians'' (Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1995). * ''1 & 2 Corinthians'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''2 Corinthians'' (Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1995). *

' (The Crossway Classic Commentaries). Crossway Books (1994). * ''Ephesians'' (Geneva Series of Commentaries). Banner of Truth (June 1, 1998). * ''The Way of Life'' (Sources of American Spirituality). Mark A. Noll, ed. Paulist Press (1987).

Notes

Sources

* ''This article includes content derived from thepublic domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work

A creative work is a manifestation of creative effort including fine artwork (sculpture, paintings, drawing, sketching, performance art), dance, writing (literature), filmmaking, ...

Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914.''

Further reading

* Adams, John H. (April 21, 2003)Charles Hodge: A voice for today’s PCUSA?

''The Layman''. * Anderson, Robert * Gutjahr Paul C. ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

; 2011) 477 pages; a standard scholarly biography

* Hicks, Peter (1997). ''The Philosophy of Charles Hodge: A 19th Century Evangelical Approach to Reason, Knowledge and Truth.'' Edwin Mellen Pr.

* Hodge, A. A. (1880). ''The life of Charles Hodge: Professor in the Theological seminary, Princeton, N.J.'' C. Scribner's sons. Reissued 1979 by Ayer Co. Pub.

* Hoffecker, W. A. (1981). ''Piety and the Princeton Theologians: Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, and Benjamin Warfield'' P&R Publishing.

* Hoffecker, W. Andrew (2011). ''Charles Hodge: The Pride of Princeton'' P&R Publishing.

* Marsden, George M. ''Fundamentalism and American Culture'' (2006)

* Noll, Mark A., ed. (2001). ''Princeton Theology, 1812–1921: Scripture, Science, and Theological Method from Archibald Alexander to Benjamin Warfield''. Baker Publishing Group.

* Stewart, J. W. and J. H. Moorhead, eds. (2002). ''Charles Hodge Revisited: A Critical Appraisal of His Life and Work''. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

External links

* * * *The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review

', 1830–82, at the University of Michigan'

"Humanities Text Initiative"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hodge, Charles 1797 births 1878 deaths 19th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians American Calvinist and Reformed theologians American abolitionists American slave owners American evangelicals Burials at Princeton Cemetery New Testament scholars Presbyterian abolitionists Presbyterian Church in the United States ministers Presidents of Calvinist and Reformed seminaries Princeton Theological Seminary alumni Princeton Theological Seminary faculty Princeton University alumni Systematic theologians 19th-century American clergy