Charles Grafton Page on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Grafton Page (January 25, 1812 May 5, 1868) was an American scientist who developed several electrical devices for which he obtained United States patents. He was also a

Crucial to Page's research with the spiral conductor was his capacity to do innovating experimenting with good results. Page did not provide an explanation for what he found, yet he extended and amplified the apparatus and its unexpected behaviors. Page's publication about his spiral instrument was well received in the American science community and in England, putting him into the upper ranks of American science at the time.

British experimenter William Sturgeon reprinted Page's article in his journal ''Annals of Electricity''. Sturgeon provided an analysis of the electromagnetic effect involved; Page drew on and expanded Sturgeon's analysis in his own later work. Sturgeon devised coils that were adaptations of Page's instrument, where battery current flowed through one, inner, segment of a coil, and electrical shock was taken from the entire length of a secondary coil.

Through the input from Sturgeon, as well as his own continuing researches, Page developed coil instruments that were the foundation for the eventual

Crucial to Page's research with the spiral conductor was his capacity to do innovating experimenting with good results. Page did not provide an explanation for what he found, yet he extended and amplified the apparatus and its unexpected behaviors. Page's publication about his spiral instrument was well received in the American science community and in England, putting him into the upper ranks of American science at the time.

British experimenter William Sturgeon reprinted Page's article in his journal ''Annals of Electricity''. Sturgeon provided an analysis of the electromagnetic effect involved; Page drew on and expanded Sturgeon's analysis in his own later work. Sturgeon devised coils that were adaptations of Page's instrument, where battery current flowed through one, inner, segment of a coil, and electrical shock was taken from the entire length of a secondary coil.

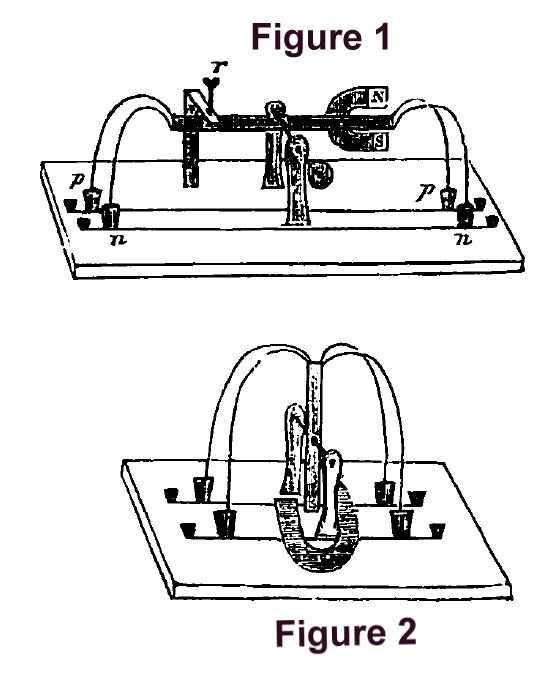

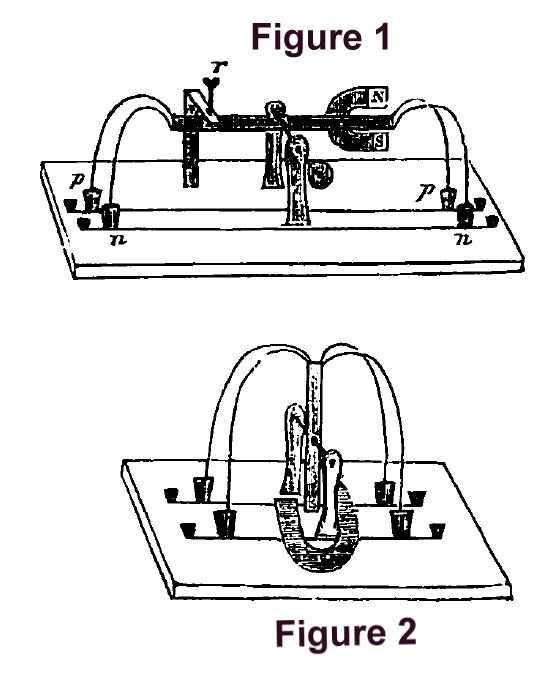

Through the input from Sturgeon, as well as his own continuing researches, Page developed coil instruments that were the foundation for the eventual  Page invented different electrical current interrupters by mechanical means so that an induction coil would produce a high voltage from a low voltage battery. One was a mechanical vibrating interrupter (Figure 1) where a piece of soft iron wire one eighth of an inch in diameter and three inches in length is covered with insulated copper wire. This configured apparatus device is made to vibrate rapidly between the North and South poles of a horseshoe shaped magnet. The wire bar mechanism is suspended in mid-air at the edge of the magnet and well balanced. The wired bar is allowed to slightly touch the poles of the magnet giving it a spring effect. The little cups of mercury (''p'' and ''n'') are sections of glass tubes for the input low voltage to the iron wire and the produced output higher voltage from the copper wire. The vibration regulator is the thumb screw ''r'' and can be adjusted to give a rapid vibration to the wire bar.

Page put together another similar oscillating interrupter (Figure 2) where there were two sets of winding insulated wires coiled in opposite directions around the main soft iron wire. The configuration was mounted on an axis differently than the first configuration at ninety degrees and the bottom end allowed to swing back and forth between the North and South poles of a horseshoe magnet. As it oscillated back and forth a higher voltage was produced from the output second set of wires than the low voltage of the input wires of the first set of wires connected to the battery. In other words, the first set of wires was connected to the positive and negative poles of the battery by way of the interrupter and the second set of wires not connected to anything had an amplified voltage many times that of the battery when the oscillating interrupter was active. It was the make and break of the first set of wires of low voltage that caused an electromagnetic field to be produced and collapse. The magnetic field oscillating like this of coming about and then collapsing caused an electric current to come out of the second set of wires because there is a relationship between magnetism and electricity. The action of one causes a reaction of the other and this law of physics is what Page discovered in his experiments. The voltage of the second set of wires was an amplified high voltage, compared to the low battery voltage that was connected to the first set of wires that was interrupted.

Page invented different electrical current interrupters by mechanical means so that an induction coil would produce a high voltage from a low voltage battery. One was a mechanical vibrating interrupter (Figure 1) where a piece of soft iron wire one eighth of an inch in diameter and three inches in length is covered with insulated copper wire. This configured apparatus device is made to vibrate rapidly between the North and South poles of a horseshoe shaped magnet. The wire bar mechanism is suspended in mid-air at the edge of the magnet and well balanced. The wired bar is allowed to slightly touch the poles of the magnet giving it a spring effect. The little cups of mercury (''p'' and ''n'') are sections of glass tubes for the input low voltage to the iron wire and the produced output higher voltage from the copper wire. The vibration regulator is the thumb screw ''r'' and can be adjusted to give a rapid vibration to the wire bar.

Page put together another similar oscillating interrupter (Figure 2) where there were two sets of winding insulated wires coiled in opposite directions around the main soft iron wire. The configuration was mounted on an axis differently than the first configuration at ninety degrees and the bottom end allowed to swing back and forth between the North and South poles of a horseshoe magnet. As it oscillated back and forth a higher voltage was produced from the output second set of wires than the low voltage of the input wires of the first set of wires connected to the battery. In other words, the first set of wires was connected to the positive and negative poles of the battery by way of the interrupter and the second set of wires not connected to anything had an amplified voltage many times that of the battery when the oscillating interrupter was active. It was the make and break of the first set of wires of low voltage that caused an electromagnetic field to be produced and collapse. The magnetic field oscillating like this of coming about and then collapsing caused an electric current to come out of the second set of wires because there is a relationship between magnetism and electricity. The action of one causes a reaction of the other and this law of physics is what Page discovered in his experiments. The voltage of the second set of wires was an amplified high voltage, compared to the low battery voltage that was connected to the first set of wires that was interrupted.

Page first observed this ringing sound in 1837 of ''galvanic music'' that came from a horseshoe magnet when it was brought close to a coil of wire of electric current that was disconnected and then reconnected. This phenomenon of electromagnetic sound was made the subject of investigation by other scientists worldwide. They concluded that the sound was due to molecular changes produced by the alternate magnetization and demagnetization of the metal and that these sound vibrations were related to the electrical interruptions. This all led to the advancement of the telephone for voice and the musical harmonic telephone. Prescott, 1884 pp. 402427 This first electromagnetic device of a horseshoe magnet converting electric power into sound is credited to Page, which the world labeled as ''the Page effect.'' M. Froment of Paris in 1846 exhibited an instrument that analysed Page's ''galvanic music'' and that was a precursor of German physicist

Page first observed this ringing sound in 1837 of ''galvanic music'' that came from a horseshoe magnet when it was brought close to a coil of wire of electric current that was disconnected and then reconnected. This phenomenon of electromagnetic sound was made the subject of investigation by other scientists worldwide. They concluded that the sound was due to molecular changes produced by the alternate magnetization and demagnetization of the metal and that these sound vibrations were related to the electrical interruptions. This all led to the advancement of the telephone for voice and the musical harmonic telephone. Prescott, 1884 pp. 402427 This first electromagnetic device of a horseshoe magnet converting electric power into sound is credited to Page, which the world labeled as ''the Page effect.'' M. Froment of Paris in 1846 exhibited an instrument that analysed Page's ''galvanic music'' and that was a precursor of German physicist

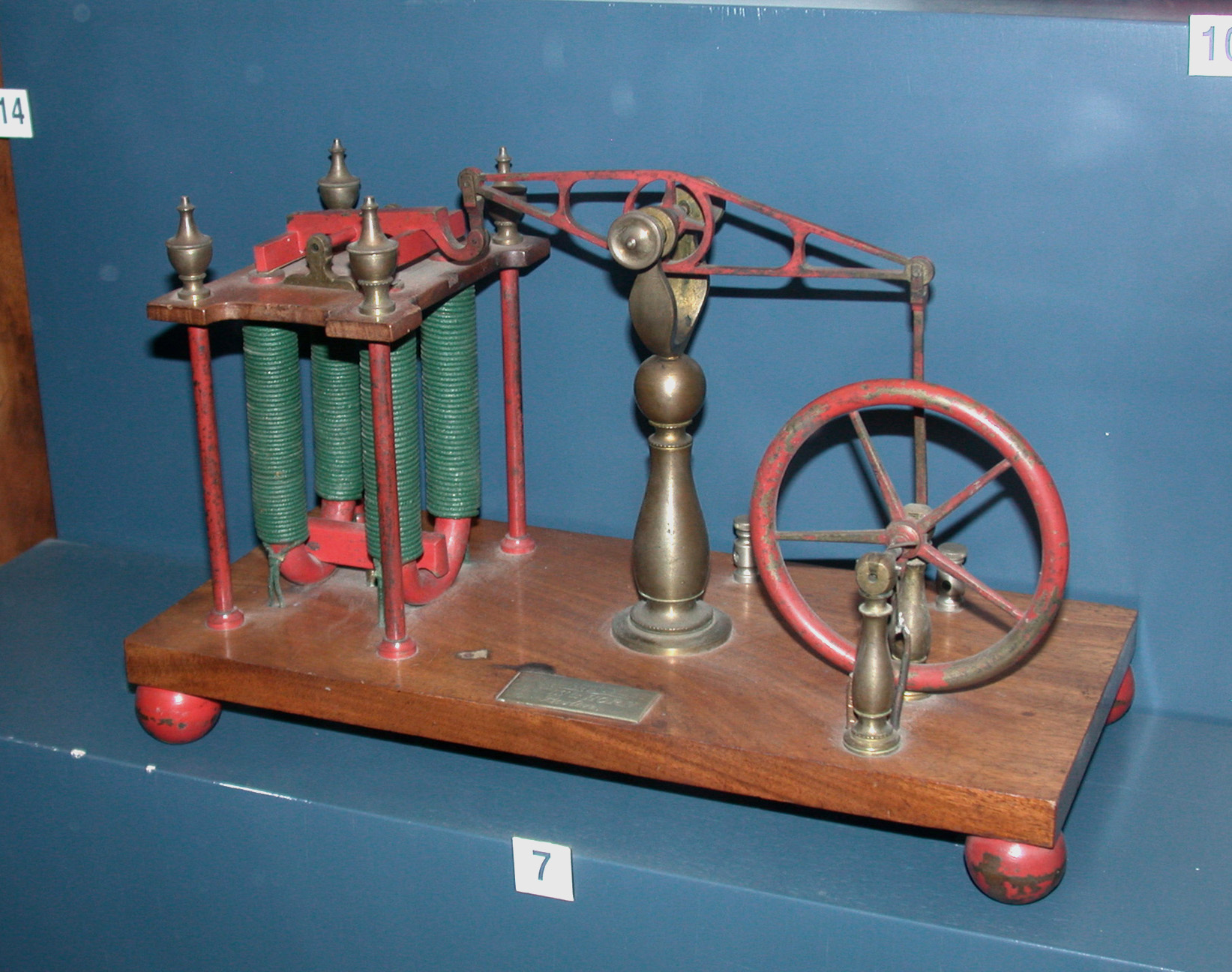

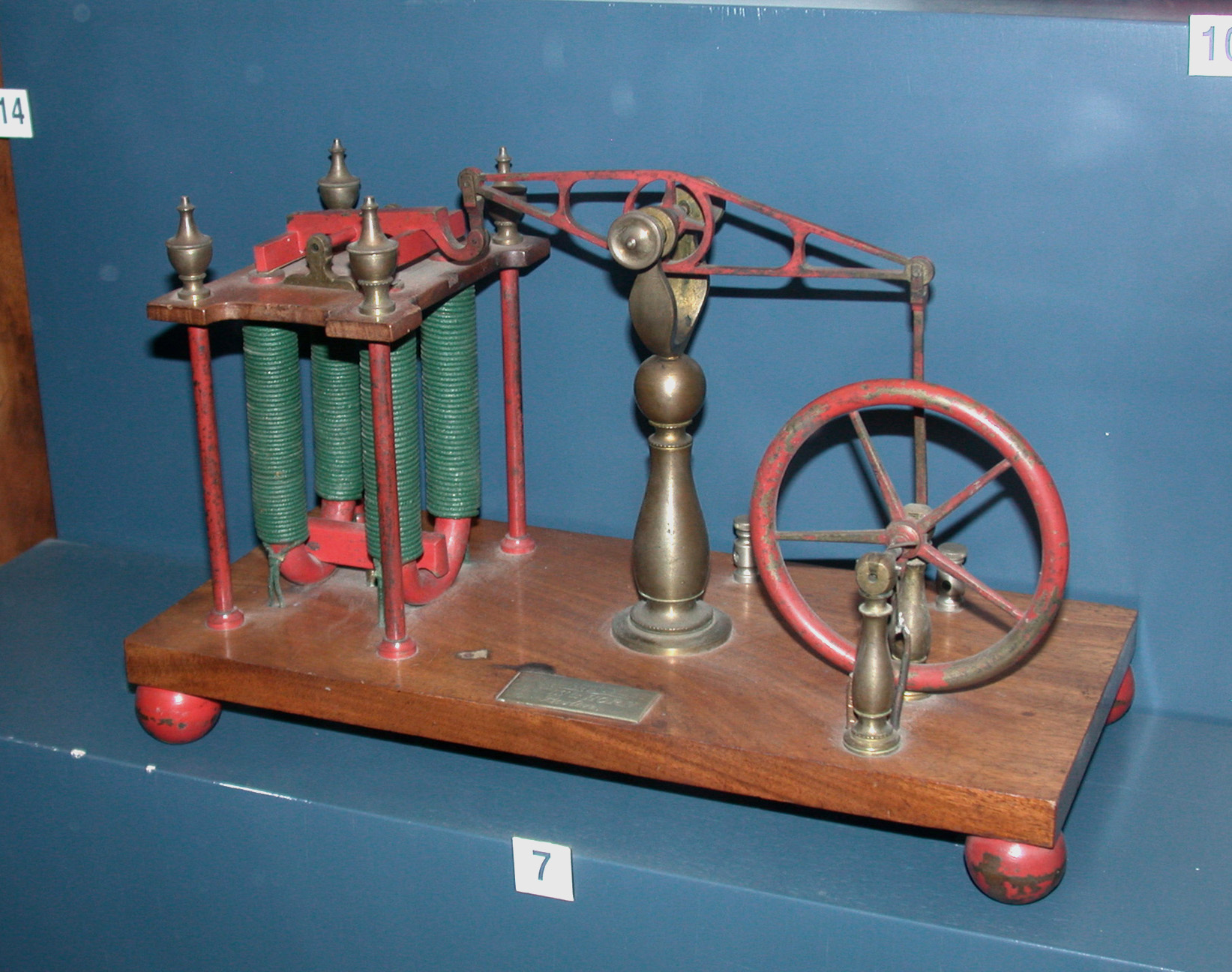

Page invented many other electromagnetic devices, some of which involved the electromagnetic motor. Many prototypes devised by Page were turned into products manufactured and marketed by Boston instrument-maker Daniel Davis, Jr., the first American to practice in magnetic philosophical instruments, scientific instruments. One such prototype is Page's electrical reciprocating motor, with patent #10,480, the model for which is at the Smithsonian Museum. While consulting with

Page invented many other electromagnetic devices, some of which involved the electromagnetic motor. Many prototypes devised by Page were turned into products manufactured and marketed by Boston instrument-maker Daniel Davis, Jr., the first American to practice in magnetic philosophical instruments, scientific instruments. One such prototype is Page's electrical reciprocating motor, with patent #10,480, the model for which is at the Smithsonian Museum. While consulting with

Page developed in the 1840s what he termed the Axial Engine. This instrument used an electromagnetic solenoid coil to draw an iron rod into its hollow interior. The rod's displacement opened a switch that stopped current from flowing in the coil; then being unattracted, the rod reverted out of the coil, and this cycle repeated again. The resulting

Page developed in the 1840s what he termed the Axial Engine. This instrument used an electromagnetic solenoid coil to draw an iron rod into its hollow interior. The rod's displacement opened a switch that stopped current from flowing in the coil; then being unattracted, the rod reverted out of the coil, and this cycle repeated again. The resulting  On April 29, 1851, Page had boosted its motors from 8 to 20 HP power with $20,000 () furnished by the United States government for development of an electric locomotive. Page conducted a full test, intending to run the locomotive from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore and back with passengers on board with the train riding on a spur of the

On April 29, 1851, Page had boosted its motors from 8 to 20 HP power with $20,000 () furnished by the United States government for development of an electric locomotive. Page conducted a full test, intending to run the locomotive from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore and back with passengers on board with the train riding on a spur of the

Works by Charles Grafton Page

at

Instruments for Natural Philosophy - Daniel Davis Jr. Apparatus

History of Induction / American Claim to Induction Coil and Its Electrostatic Developments By Charles Grafton Page (1867)Psychomancy : spirit-rappings and table-tippings exposed. Page, 1853

{{DEFAULTSORT:Page, Charles Grafton American physicists 19th-century American inventors People associated with electricity 19th-century American people 1812 births 1868 deaths People from Salem, Massachusetts Harvard Medical School alumni Harvard College alumni

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, patent examiner A patent examiner (or, historically, a patent clerk) is an employee, usually a civil servant with a scientific or engineering background, working at a patent office. Major employers of patent examiners are the European Patent Office (EPO), the Unit ...

, and college professor of chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

. Like contemporaries Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smith ...

and Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, Page began his career as a naturally curious investigator who conducted original research

Research is "creativity, creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular att ...

through direct observation and experimentation. Through his experimentation, Page helped develop a scientific understanding of the principles of electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

. Page served as a patent examiner at the United States Patent Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alexa ...

, where his knowledge of electromagnetism was useful in the innovation process and in his own desire to develop electromagnetic locomotion. His work had a lasting impact on telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

and in the practice and politics of patenting scientific innovation. Page's views of patenting innovations challenged a commonly held belief at the time that maintained that scientists do not patent their inventions.

Through his investigations of inductive coils, Page developed a device which he called the ''dynamic multiplier''. In this device, an electrical impulse is provided to the inductive coil, resulting in a high voltage. In certain configurations of Page's device that involve an electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in the ...

, the impulse provided to the device results in an audio tone. Page called this "galvanic music". Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

and others developed telephone technology based on this peculiar electro-acoustic phenomenon.

Page advocated the use of electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatry, psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders.Rudorfer, MV, Henry, ME, Sackeim, HA (2003)"Electroco ...

as a medical treatment. He believed that electrical voltages higher than the typical low voltage of batteries would result in medical benefits.

Early family life

Charles Grafton Page was born to Captain Jere Lee Page and Lucy Lang Page on January 25, 1812, in Salem, Massachusetts. He was a descendant of John Page who had come from England in 1630 and settled in Massachusetts. Having eight siblings, four of each gender, he was the only one of five sons to pursue a career into mature adulthood. One of his brothers died in infancy. His brother George died from typhoid at age sixteen, his brother Jery perished on a sea expedition to the Caribbean at age twenty-five, and Henry, afflicted by poliomyelitis, was not able to support himself. In writing to Page during his final ill-fated voyage Jery expressed the family's hope for his success. Page's curiosity about electricity was evident from childhood. At age nine, he climbed on top of his parents' house with a fire-shovel in an attempt to catch electricity during a thunderstorm. Lane, 1869 p.2 At age ten, he built an electrostatic machine that he used to give his friends electric shocks. At sixteen, Page developed the "portable electrophorus," which served as the foundation for his first published article in ''American Journal of Science'' ("Notice of some New Electrical Instruments", 1834). Page's other early interests includedbotany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

, and floriculture

Floriculture, or flower farming, is a branch of horticulture concerned with the cultivation of flowering and ornamental plants for gardens and for floristry, comprising the floral industry. The development of new varieties by plant breeding is ...

which contributed to his scientific training and later hobbies and pastimes.

Mid life and education

Page prepared for college in the Salem Grammar School under the charge of Theodore Eames. He entered Harvard College in 1828 when he was 16 years old graduating in 1832, Malone, 1934 ''Page, Charles Grafton'', p. 136 studying medicine with A. L. Peirson at Harvard Medical School. In 1836, he received the degree for being a Medical Doctor. Essex Institute of Salem, Massachusetts, p. 22 AtHarvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

he studied chemistry under John White Webster. Henry Wheatland, a classmate at Salem Latin School who also attended college and medical school with him, described Page as popular, fun-loving, athletic, a fine singer and "a loved companion". Page participated in organizing a college chemical club where he demonstrated electricity and other phenomena. While pursuing a medical degree

A medical degree is a professional degree admitted to those who have passed coursework in the fields of medicine and/or surgery from an accredited medical school. Obtaining a degree in medicine allows for the recipient to continue on into special ...

from Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is consi ...

in 1836, he gave lectures in chemistry to college students.

Page continued to reside in his parents' Salem home in Virginia from 1838 and opened a small medical practice after graduating becoming a medical doctor for two years. In a well-stocked lab that he set up there, he experimented with electricity, demonstrated effects that no one had observed before, and constructed original electromagnetic mechanisms that intensified these effects. Cavicchi, 2008 p. 893 In 1838, his father retired from a successful career as a sea captain in trade with East India. In 1840, he relocated his entire family to Fairfax County

Fairfax County, officially the County of Fairfax, is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is part of Northern Virginia and borders both the city of Alexandria and Arlington County and forms part of the suburban ring of Washington, D.C. ...

in rural Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

some five miles from Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, where he purchased a half-section of land containing . Post, 1976 ''Physics, Patents, and Politics'', p. 7

In 1840 he took a position in the US Patent Office as an examiner. Page continued his experimental research and set up a medical practice as a country doctor for a few years when he had moved to northern Virginia with his parents. His new career was not very fruitful and in 1840 he was forced to sell off his prized possession, an entomological cabinet insect collection, to support himself. He ran an ad for it in ''Silliman's Journal

The ''American Journal of Science'' (''AJS'') is the United States of America's longest-running scientific journal, having been published continuously since its conception in 1818 by Professor Benjamin Silliman, who edited and financed it himsel ...

,'' selling it for $400 (). Page visited Washington, D.C., often and moved there in 1842. He was Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy from 1844 to 1849 in the Medical Department at Columbian College in Washington, D. C. (now George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, preside ...

). He held other public roles also such as that of advising the choice of stone to be used in constructing the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

and the Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk shaped building within the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, once commander-in-chief of the Continental Army (1775–1784) in the American Revolutionary War and the ...

to the committees in charge of these projects.

Career

Page worked in Washington, D.C., as a patent examiner for the U.S. Patent Office from 1853 through 1860. Page was a patent agent in 1853, 1854, and 1855 handling up to 50 successful patents a year. He processed patents forEben Norton Horsford

Eben Norton Horsford (27 July 1818 – 1 January 1893) was an American scientist who taught agricultural chemistry in the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard from 1847 to 1863. Later he was known for his reformulation of baking powder, his int ...

, a Harvard professor; Walter Hunt, inventor of the safety pin and sewing machine; Birdsill Holly

Birdsill Holly Jr. (November 8, 1820 – April 27, 1894) was an American mechanical engineer and inventor of water hydraulics devices. He is known for inventing mechanical devices that improved city water systems and patented an improved fire hy ...

, various mechanical devices; Theodore Weed, sewing machine mechanisms; Thomson Newbury, machine-tool attachments; John North, paper folding machines; Lysander Button, fire engine hydraulic paraphernalia with Robert Blake, who together created in 1860 the firm 'Button and Blake' that dominated the fire engine business in the United States for several years. Page was a patent counselor to friends like Ari Davis, who constructed mechanical apparatus and electrical devices for others and their inventions. Post, 1976 ''Physics, Patents, and Politics'', p. 159

The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

affected the Patent Office as much as the new administration of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

did. The number of patent applications in 1860 was 7,653. In 1861, this dropped some 3,000 to about 4,600 applications. The office was required by law to be self-supporting but the commissioner under Lincoln throughout the war had a wake of dismissals. Sixteen examiners were authorized, however less than half that were filled by him. In addition in governing the department he demoted the examiners and paid them the salary for assistants. The amount of applications increased as the war went on and by 1864 was within 800 of the pre-war high and was over 10,000 in 1865. The examiners of the short staff had to handle three times that processed in the 1850s. Mindful accurate examinations were out of the question and a lackadaisical attitude came about to process the applications. Page passed nearly every application given to him to process, even without correcting the wording of the claim if wrong. Congress in time authorized a supplementary appropriation and the number of examiners was increased to twelve. However the examiners on staff were not paid any more and Page struggled to provide for his nearly dozen dependents on a monthly income of $150 ().

The time of the civil war was not a lucrative time for Page and in addition the Patent Office was partly converted to an army hospital so the environment around him was daunting. The war wreaked a further devastating impact on Page's scientific work and legacy. In 1863, Union soldiers stationed in the area of Page's home, broke into his laboratory as a random, unprovoked act of violence. His equipment, inventions and laboratory notebooks were destroyed. Some other inventions by Page which he had donated to the Smithsonian Institution were destroyed by a fire there in 1865. As a result of these destructive events, very few of Page's handmade devices exist today.

Page figured as a key witness in the Morse v. O'Reilly telegraph lawsuit of 1848. However, when Morse sought an extension of his patent on telegraph apparatus twelve years later, Page refuted Morse's role as inventor and was perhaps influential in the extensions' denial. Throughout his life, Page published more than one-hundred articles over the course of three distinct periods: the late 1830s, the mid-1840s, and the early 1850s. The first period (1837–1840) was especially crucial in developing his analytic skills. Over 40 of his articles appeared in ''American Journal of Science'' edited by Benjamin Silliman

Benjamin Silliman (August 8, 1779 – November 24, 1864) was an early American chemist and science educator. He was one of the first American professors of science, at Yale College, the first person to use the process of fractional distillat ...

; some of these were reprinted at the time in William Sturgeon

William Sturgeon (22 May 1783 – 4 December 1850) was an English physicist and inventor who made the first electromagnets, and invented the first practical British electric motor.

Early life

Sturgeon was born on 22 May 1783 in Whittington, ...

’s ''Annals of Electricity, Magnetism'' printed in Great Britain. The ''Royal Society Catalogue of Scientific Papers'' (1800–1863 volume) records many of Page's papers, however this listing is incomplete.

Scientific accomplishments

Self-inductive coil

While still a medical student at Harvard, Page conducted a ground-breaking experiment which demonstrated the presence of electricity in an arrangement of a spiral conductor that no one had tried before. His experiment was a response to a short paper byJoseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smith ...

, announcing that a strong electric shock

Electrical injury is a physiological reaction caused by electric current passing through the body. The injury depends on the density of the current, tissue resistance and duration of contact. Very small currents may be imperceptible or produce ...

was obtained from a ribbon strip of copper, spiralled up between fabric insulation, at the moment when battery current stopped running in this conductor. These strong shocks manifested the electrical property of self-inductance

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The flow of electric current creates a magnetic field around the conductor. The field strength depends on the magnitude of the ...

which Faraday had identified in researches published prior to Henry's publication, building on his own landmark discovery of electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1831, and James Clerk ...

. Page was not aware of Faraday's research on electricity that had inspired Henry to write his paper. He did his own experimentation to come to his own conclusions.

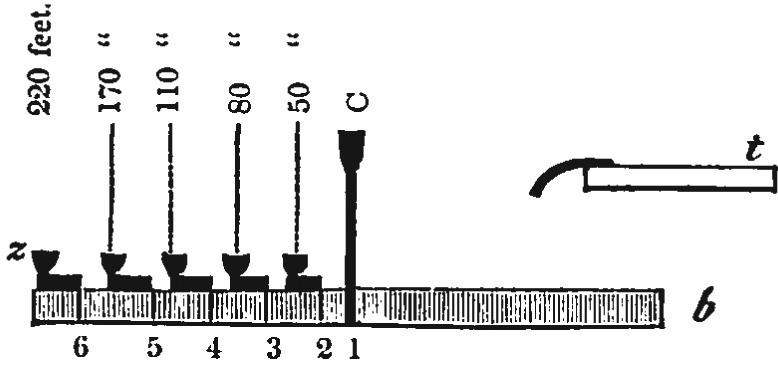

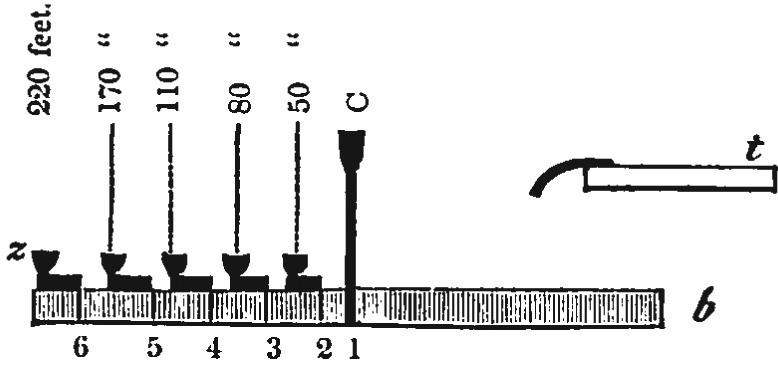

Page's innovation was to construct a spiral conductor having cups filled with mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

as electrical connectors that were placed at various positions along its length. He then connected a contact post from an electrochemical battery to the inner cup of the spiral, and put the other battery contact point into some other cup of the spiral. The direct battery current flowed through the spiral, from cup to cup. He held a metal wand in each hand, and put these wands into the same two cups as where the battery terminals went — or any other pair of cups. When an assistant removed one of the battery terminals, stopping the current from going in the spiral, Page received a shock. He reported stronger shocks when his hands covered more of the spiral's length than where direct battery current went. He even felt shocks from parts of the spiral where no direct battery current passed. He used acupuncture

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientifi ...

needles, pierced into his fingers, to amplify his sense of shock. Cavicchi, 2005 ''Spark, Shocks, and Voltage Traces'', pp. 123-136

Page advocated the use of this shocking therapy device as a medical treatment known as ''galvanism'', an early form of electrotherapy

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment. In medicine, the term ''electrotherapy'' can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological dise ...

. His interest lay in heightening of electrical tension, or voltage

Voltage, also known as electric pressure, electric tension, or (electric) potential difference, is the difference in electric potential between two points. In a static electric field, it corresponds to the work needed per unit of charge to m ...

above that of the low voltage battery input, and in its other electrical behaviors. Page went on to improve the inductive coil building a particularly effective instrument and giving it the name 'Dynamic Multiplier'. In order for Page's instrument to produce the shock, the battery current had to be stopped. In order to experience another shock, the battery had to be started again, and then stopped. This technique led Page to invent the first interrupter

An interrupter in electrical engineering is a device used to interrupt the flow of a steady direct current for the purpose of converting a steady current into a changing one. Frequently, the interrupter is used in conjunction with an inductor (c ...

s to provide a repeatable means of connecting and disconnecting the circuit. In these devices, electrical flow is started and stopped as a rocking or rotary motion lifts electrical contacts out of a mercury pool. An electric motor

An electric motor is an Electric machine, electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a Electromagneti ...

effect is responsible for the continued operation of the switch.

Crucial to Page's research with the spiral conductor was his capacity to do innovating experimenting with good results. Page did not provide an explanation for what he found, yet he extended and amplified the apparatus and its unexpected behaviors. Page's publication about his spiral instrument was well received in the American science community and in England, putting him into the upper ranks of American science at the time.

British experimenter William Sturgeon reprinted Page's article in his journal ''Annals of Electricity''. Sturgeon provided an analysis of the electromagnetic effect involved; Page drew on and expanded Sturgeon's analysis in his own later work. Sturgeon devised coils that were adaptations of Page's instrument, where battery current flowed through one, inner, segment of a coil, and electrical shock was taken from the entire length of a secondary coil.

Through the input from Sturgeon, as well as his own continuing researches, Page developed coil instruments that were the foundation for the eventual

Crucial to Page's research with the spiral conductor was his capacity to do innovating experimenting with good results. Page did not provide an explanation for what he found, yet he extended and amplified the apparatus and its unexpected behaviors. Page's publication about his spiral instrument was well received in the American science community and in England, putting him into the upper ranks of American science at the time.

British experimenter William Sturgeon reprinted Page's article in his journal ''Annals of Electricity''. Sturgeon provided an analysis of the electromagnetic effect involved; Page drew on and expanded Sturgeon's analysis in his own later work. Sturgeon devised coils that were adaptations of Page's instrument, where battery current flowed through one, inner, segment of a coil, and electrical shock was taken from the entire length of a secondary coil.

Through the input from Sturgeon, as well as his own continuing researches, Page developed coil instruments that were the foundation for the eventual induction coil

An induction coil or "spark coil" (archaically known as an inductorium or Ruhmkorff coil after Heinrich Rühmkorff) is a type of electrical transformer used to produce high-voltage pulses from a low-voltage direct current (DC) supply. p.98 To ...

. Cavicchi, 2006, pp. 319-361 These instruments had two wires. One wire, termed the ''primary'', carried battery current; a shock was taken at the ends of the other much longer wire, termed the ''secondary'' (see transformer

A transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces a varying magnetic flux in the transformer' ...

). The primary wire was wound side by side one layer thick over an iron core; the secondary wire was wound over that several layers thick. Page developed a deep understanding of the underlying electromagnetic principles. In Page's published account of his coil, he termed it

and its contact breaker the 'Compound Electro-Magnet and Electrotome'. Page's patent model for this coil is on display at Smithsonian National Museum of America's History.

Page invented different electrical current interrupters by mechanical means so that an induction coil would produce a high voltage from a low voltage battery. One was a mechanical vibrating interrupter (Figure 1) where a piece of soft iron wire one eighth of an inch in diameter and three inches in length is covered with insulated copper wire. This configured apparatus device is made to vibrate rapidly between the North and South poles of a horseshoe shaped magnet. The wire bar mechanism is suspended in mid-air at the edge of the magnet and well balanced. The wired bar is allowed to slightly touch the poles of the magnet giving it a spring effect. The little cups of mercury (''p'' and ''n'') are sections of glass tubes for the input low voltage to the iron wire and the produced output higher voltage from the copper wire. The vibration regulator is the thumb screw ''r'' and can be adjusted to give a rapid vibration to the wire bar.

Page put together another similar oscillating interrupter (Figure 2) where there were two sets of winding insulated wires coiled in opposite directions around the main soft iron wire. The configuration was mounted on an axis differently than the first configuration at ninety degrees and the bottom end allowed to swing back and forth between the North and South poles of a horseshoe magnet. As it oscillated back and forth a higher voltage was produced from the output second set of wires than the low voltage of the input wires of the first set of wires connected to the battery. In other words, the first set of wires was connected to the positive and negative poles of the battery by way of the interrupter and the second set of wires not connected to anything had an amplified voltage many times that of the battery when the oscillating interrupter was active. It was the make and break of the first set of wires of low voltage that caused an electromagnetic field to be produced and collapse. The magnetic field oscillating like this of coming about and then collapsing caused an electric current to come out of the second set of wires because there is a relationship between magnetism and electricity. The action of one causes a reaction of the other and this law of physics is what Page discovered in his experiments. The voltage of the second set of wires was an amplified high voltage, compared to the low battery voltage that was connected to the first set of wires that was interrupted.

Page invented different electrical current interrupters by mechanical means so that an induction coil would produce a high voltage from a low voltage battery. One was a mechanical vibrating interrupter (Figure 1) where a piece of soft iron wire one eighth of an inch in diameter and three inches in length is covered with insulated copper wire. This configured apparatus device is made to vibrate rapidly between the North and South poles of a horseshoe shaped magnet. The wire bar mechanism is suspended in mid-air at the edge of the magnet and well balanced. The wired bar is allowed to slightly touch the poles of the magnet giving it a spring effect. The little cups of mercury (''p'' and ''n'') are sections of glass tubes for the input low voltage to the iron wire and the produced output higher voltage from the copper wire. The vibration regulator is the thumb screw ''r'' and can be adjusted to give a rapid vibration to the wire bar.

Page put together another similar oscillating interrupter (Figure 2) where there were two sets of winding insulated wires coiled in opposite directions around the main soft iron wire. The configuration was mounted on an axis differently than the first configuration at ninety degrees and the bottom end allowed to swing back and forth between the North and South poles of a horseshoe magnet. As it oscillated back and forth a higher voltage was produced from the output second set of wires than the low voltage of the input wires of the first set of wires connected to the battery. In other words, the first set of wires was connected to the positive and negative poles of the battery by way of the interrupter and the second set of wires not connected to anything had an amplified voltage many times that of the battery when the oscillating interrupter was active. It was the make and break of the first set of wires of low voltage that caused an electromagnetic field to be produced and collapse. The magnetic field oscillating like this of coming about and then collapsing caused an electric current to come out of the second set of wires because there is a relationship between magnetism and electricity. The action of one causes a reaction of the other and this law of physics is what Page discovered in his experiments. The voltage of the second set of wires was an amplified high voltage, compared to the low battery voltage that was connected to the first set of wires that was interrupted.

Telephone technology

Page mounted a spiral conductor rigidly between the North and South poles of a suspended horseshoe magnet in a subsequent test trial exercise. When current stopped in the spiral, a ringing tone could be heard from the magnet, which Page termed ''galvanic music''. Two notes were heard, one was the proper natural musical tone of the magnet and the other was an octave higher. It was after studying this phenomenon thatAlexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

progressed to inventing the telephone decades later. Other electrical engineers cited Page's electro-acoustic ''galvanic music'' mechanical vibrations as an important precedent for the development of telephone technology. Johann Philipp Reis

Johann Philipp Reis (; 7 January 1834 – 14 January 1874) was a self-taught German scientist and inventor. In 1861, he constructed the first ''make-and-break'' telephone, today called the Reis telephone.

Early life and education

Reis ...

constructed a telephone that produced a musical note based on Page's technology.

Page first observed this ringing sound in 1837 of ''galvanic music'' that came from a horseshoe magnet when it was brought close to a coil of wire of electric current that was disconnected and then reconnected. This phenomenon of electromagnetic sound was made the subject of investigation by other scientists worldwide. They concluded that the sound was due to molecular changes produced by the alternate magnetization and demagnetization of the metal and that these sound vibrations were related to the electrical interruptions. This all led to the advancement of the telephone for voice and the musical harmonic telephone. Prescott, 1884 pp. 402427 This first electromagnetic device of a horseshoe magnet converting electric power into sound is credited to Page, which the world labeled as ''the Page effect.'' M. Froment of Paris in 1846 exhibited an instrument that analysed Page's ''galvanic music'' and that was a precursor of German physicist

Page first observed this ringing sound in 1837 of ''galvanic music'' that came from a horseshoe magnet when it was brought close to a coil of wire of electric current that was disconnected and then reconnected. This phenomenon of electromagnetic sound was made the subject of investigation by other scientists worldwide. They concluded that the sound was due to molecular changes produced by the alternate magnetization and demagnetization of the metal and that these sound vibrations were related to the electrical interruptions. This all led to the advancement of the telephone for voice and the musical harmonic telephone. Prescott, 1884 pp. 402427 This first electromagnetic device of a horseshoe magnet converting electric power into sound is credited to Page, which the world labeled as ''the Page effect.'' M. Froment of Paris in 1846 exhibited an instrument that analysed Page's ''galvanic music'' and that was a precursor of German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Association, ...

's experiment showing an electrical impulse of a certain vibration rate sent down a telegraph wire could cause a tuning fork at a far distance to resonate at that same rhythm.

Electric motor

Page invented many other electromagnetic devices, some of which involved the electromagnetic motor. Many prototypes devised by Page were turned into products manufactured and marketed by Boston instrument-maker Daniel Davis, Jr., the first American to practice in magnetic philosophical instruments, scientific instruments. One such prototype is Page's electrical reciprocating motor, with patent #10,480, the model for which is at the Smithsonian Museum. While consulting with

Page invented many other electromagnetic devices, some of which involved the electromagnetic motor. Many prototypes devised by Page were turned into products manufactured and marketed by Boston instrument-maker Daniel Davis, Jr., the first American to practice in magnetic philosophical instruments, scientific instruments. One such prototype is Page's electrical reciprocating motor, with patent #10,480, the model for which is at the Smithsonian Museum. While consulting with Samuel F.B. Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

and Alfred Lewis Vail on the improvement of the telegraph, Page contributed to the adoption of suspended wires using a ground return and designed a signal receiver magnet. He also tested magneto-electricity as a potential source for replacing steam power. He was a person of moderate means and could not devote full time to his scientific work which resulted in slow progress. Malone, 1934 ''Page, Charles Grafton'', p. 137

Electromagnetic locomotive

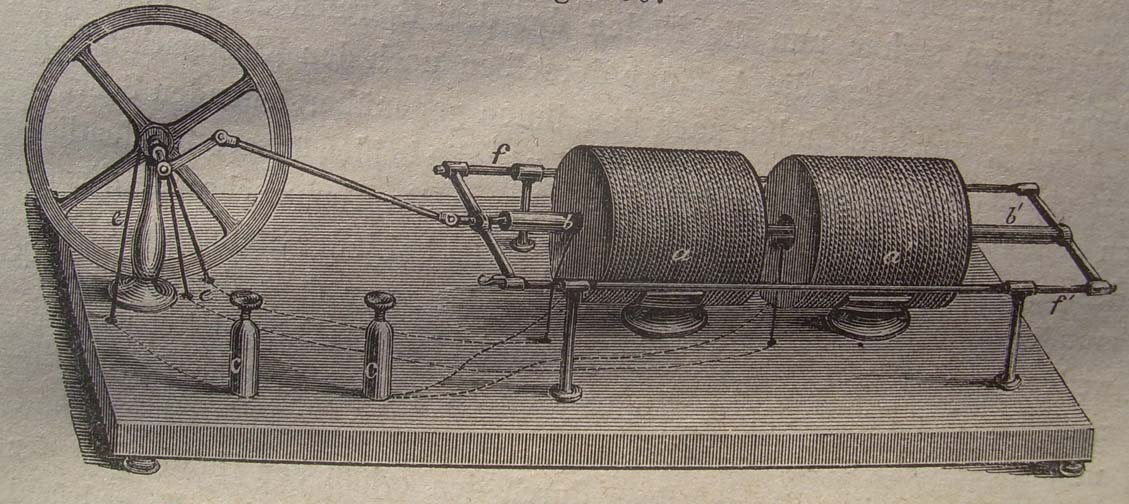

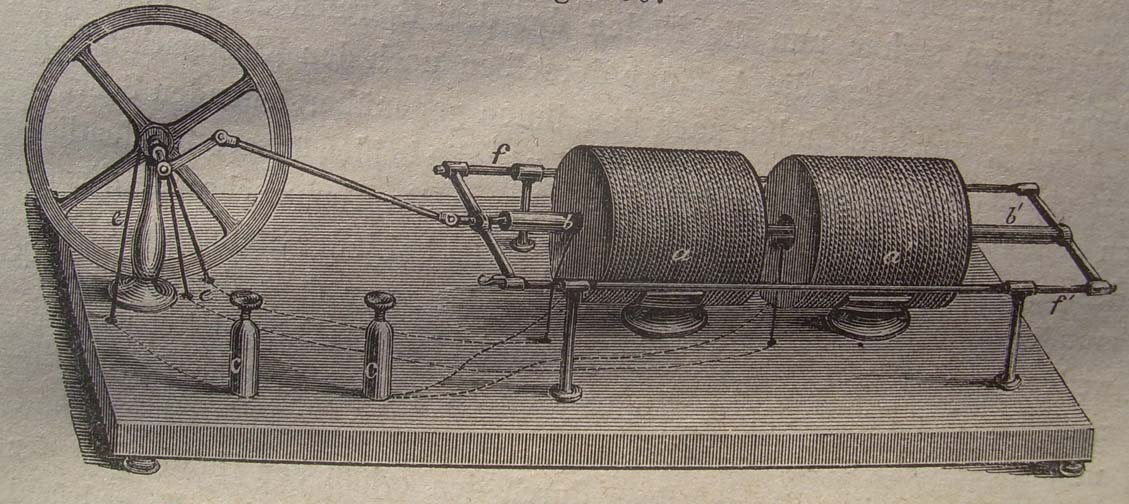

Page developed in the 1840s what he termed the Axial Engine. This instrument used an electromagnetic solenoid coil to draw an iron rod into its hollow interior. The rod's displacement opened a switch that stopped current from flowing in the coil; then being unattracted, the rod reverted out of the coil, and this cycle repeated again. The resulting

Page developed in the 1840s what he termed the Axial Engine. This instrument used an electromagnetic solenoid coil to draw an iron rod into its hollow interior. The rod's displacement opened a switch that stopped current from flowing in the coil; then being unattracted, the rod reverted out of the coil, and this cycle repeated again. The resulting reciprocating motion

Reciprocating motion, also called reciprocation, is a repetitive up-and-down or back-and-forth linear motion. It is found in a wide range of mechanisms, including reciprocating engines and pumps. The two opposite motions that comprise a single r ...

of the rod back and forth, into and out of the coil, was converted to rotary motion by the mechanism. After demonstrating uses of this engine to run saws and pumps, Page successfully petitioned the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

for funds to produce an electromagnetic locomotive, based on this design.

With these funds plus personal resources that took him into debt, Page built and tested the first full-sized electromagnetic locomotive, preceded only by the 1842 battery-powered model-sized ''Galvani'' of Scottish inventor Robert Davidson. Along the way, Page constructed a series of motors, revisions of the axial engine having different dimensions and mechanical features, which he tested thoroughly. The motor operated on large electrochemical cells, acid batteries having as electrodes zinc and costly platinum, with fragile clay diaphragms between the cells. Page's 1850 American Association for Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific respons ...

presentation about his progress impressed Joseph Henry, Benjamin Silliman and other leading scientists.

On April 29, 1851, Page had boosted its motors from 8 to 20 HP power with $20,000 () furnished by the United States government for development of an electric locomotive. Page conducted a full test, intending to run the locomotive from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore and back with passengers on board with the train riding on a spur of the

On April 29, 1851, Page had boosted its motors from 8 to 20 HP power with $20,000 () furnished by the United States government for development of an electric locomotive. Page conducted a full test, intending to run the locomotive from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore and back with passengers on board with the train riding on a spur of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

track. Post, 1972 p. 140 With some periods of steady running, the nearly silent engine traveled to Bladensburg, Maryland

Bladensburg is a town in Prince George's County, Maryland. The population was 9,657 at the 2020 census. Areas in Bladensburg are located within ZIP code 20710. Bladensburg is from central Washington.

History

Originally called Garrison's Landi ...

, at a top speed of . Prospective passengers were afraid to go on a train traveling at such a high speed.

Problems came about on the inaugural trip with high voltage

High voltage electricity refers to electrical potential large enough to cause injury or damage. In certain industries, ''high voltage'' refers to voltage above a certain threshold. Equipment and conductors that carry high voltage warrant spec ...

sparks, resulting from effects Page later investigated as problems with the spiral conductor. The sparking broke through the insulation

Insulation may refer to:

Thermal

* Thermal insulation, use of materials to reduce rates of heat transfer

** List of insulation materials

** Building insulation, thermal insulation added to buildings for comfort and energy efficiency

*** Insulated ...

of the electrical coils resulting in short circuit

A short circuit (sometimes abbreviated to short or s/c) is an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path with no or very low electrical impedance. This results in an excessive current flowing through the circuit ...

s. Page and his mechanic Ari Davis struggled to keep the locomotive operating, making necessary repairs as they went along. They reversed direction once arriving at Bladensburg for what became a troublesome problematic return to Washington, D.C.

The railroad vehicle was capable of carrying several passengers in addition to an operating crew. It had a wheel arrangement of 4-2-0 and constructed like an ordinary passenger rail-wagon coach with a fifteen foot long arch-roof and a six feet wide body. The train superstructure supported the forward truck end of the transport with four ordinary 30-inch steel wheels and the rear end was supported on two five foot high driving wheels. The woodwork of the carrier was constructed by a common house carpenter who had never seen close-up a train carriage being built. The driving wheels were assembled by mechanics not used to making mechanisms that complicated so were not put together with precision and were misaligned. As a result of Page's poor engineering for the project his railway train was a shameful result unworthy of the position it was to occupy in history.

The power for propelling the first all electric passenger train was furnished by one hundred Grove cell

The Grove cell was an early electric primary cell named after its inventor, Welsh physical scientist William Robert Grove, and consisted of a zinc anode in dilute sulfuric acid and a platinum cathode in concentrated nitric acid, the two separated ...

batteries carried under the carriage floor in an oblong trough between the driving wheels where the boiler and firebox were normally located in a typical train engine. The cells were 100 square inches each of a pair of electrode dividers. Many of the fragile battery cell clay dividers cracked and broke down during the jarring and shaking operation of the locomotive engine. In addition the consumption of zinc was immense, so between these two maintenance items the expense of running a battery operated locomotive was prohibitive in a commercial application.

The failures of Page's electromagnetic locomotive test run were cautionary to other inventors who eventually found other means than batteries to produce electrically driven locomotion. Before Page began his attempt, work such as that of James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule (; 24 December 1818 11 October 1889) was an English physicist, mathematician and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work (see energy). Th ...

had generated a general consensus among scientists that the battery powered electric engine was an impractical device. Page had disregarded those findings and never gave up believing in the potential of his design of an on-board electric source for locomotive power.

Unmasking pseudoscience

Comfortable himself in public performance as a popular lecturer and singer, being skilled in ventriloquism as well, Page was astute in detecting the misuse of performative acts in defrauding a gullible public. One class of fraudulent schemes prevalent at the time involved communications with spirits by means of rapping sounds, the motion of a table, or other such signs produced in the vicinity of the perpetrator-medium. The sounds and motions were attributed to occult forces and forms of electricity. TheFox sisters

The Fox sisters were three sisters from Rochester, New York who played an important role in the creation of Spiritualism: Leah (April 8, 1813 – November 1, 1890), Margaretta (also called Maggie), (October 7, 1833 – March 8, 1893) and Catheri ...

, of Rochester New York, made these claims notorious by exhibiting in public and private settings, while collecting money from their audiences. Page's efforts to expose these frauds at their human roots stems in part from his keen concern for furthering the public understanding of science and their proficient use of its findings and benefits. In this undertaking, Page allied with contemporary Michael Faraday and other scientists who have sought to debunk the unscrupulous applications of pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or falsifiability, unfa ...

upon a willing and gullible public.

Investigating some of these performers in person, Page produced a book titled ''Psychomancy: spirit-rappings and table-tippings exposed'' that uncovers various means of deception they employed. He described his analysis of these techniques during a sitting with the Fox sisters. Each time a critical observer peered under the table around which the sisters were seated, the spirit rapping ceased; whenever the observer sat upright, the sounds recommenced. Page asked to have the spirit sounds displayed elsewhere than via the table. One sister climbed into a wardrobe closet. Page identified where her long dress (concealing a stick or other apparatus) contacted the wardrobe. Through his expert knowledge of ventriloquism, Page detected how this performer was misdirecting the viewer's attention away from the actual source of the sound while building expectations to suppose the sound came from elsewhere than the source. However the trick was "poorly done" and the girl could not control it so as to produce any spirit communication.

Going on to reveal other fraudulent practices, Page addressed the relationship at work between performer and audience by which both functioned as perpetrators. He said that the prime movers in all these so-called miracles were impostors, and that those who believed them were gullible. While the former was filling their coffers at the expense of the latter, they often indulged in secret amusement at the faith of their supporters. This was particularly true at the consultations of the learned clergy and others upon electricity and magnetism considered the new fluid of the devil's immediate agency as the probable cause of these strange phenomena.

Controversy and impact from politics, war, and patents

Page's scientific undertakings brought him into public arenas where politics and controversy held sway. A tension early to arise in his career as patent examiner was that of the conflict of interest between the privileged information he had regarding applicants' patents, and his private consulting with particular inventors on the side. Following his appearance in the 1848 Morse v O'Reilly lawsuit over the telegraph, Page took a more careful stance in his role as patent examiner. Thereafter, he refrained from transmitting such privileged information to rival patent applicants. However, the well-paid public post of patent examiner put the occupants continually under scrutiny by politicians, scientists, and aspiring inventors. Both Congress and the executive branch exerted control and influence over policy and practices in the patent office. In the early years of theUnited States Patent and Trademark Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alexa ...

, a patent examiner was expected to be highly trained, knowledgeable in all the sciences, informed on current and past technology. Page was an exemplar of this ideal and became the chief patent examiner. As Page continued in the job of senior examiner he developed a keen eye for detecting fraudulent scientific claims, although he was a patent advocate.

The number of patents submitted to the agency in his time at the prestigious job increased sharply, however the number of patents granted was the same or less, and the number of patent examiners was unchanged. Inventors seeking patents, becoming incensed about decisions made against them, coalesced into a lobby with a voice projected through the journal ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

''. This lobby advocated "liberalization" — more leniency in the granting of patents, giving the inventor the "benefit of the doubt"— and argued against the scientific research being sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution under Joseph Henry.

Henry took a hard line, decrying inventors' "futile attempts to innovate and improve". The elite professionalized science that Henry was building up through the Smithsonian and other organizations treated as low status the having or seeking of a patent; patents were not considered a contribution to science. While Page set out to show that gaining patents was genuine scientific work, he fell out of favor with the scientific establishment. His friendship with Henry petered out, and Page was no longer held in high regard as part of elite science.

Page shifted in his position on the granting of patents. As an examiner of patents, he was scrupulous and fair. Through his own experience as an inventor and association with other inventors, he allied with their concerns. On his resignation from the patent agency, Page used the ''American Journal of Science'' as a forum to critique and even lambast the agency and policies which he had upheld for 10 years prior. He had played a role in shaping government customs when inside the patent office and now in reshaping the policies from an outside view.

Page found a political ally in Thomas Hart Benton, senator from Missouri. Benton requested funds for Page to develop a warship powered on electromagnetism. This petition met with serious opposition in the Senate. Senator Henry Stuart Foote

Henry Stuart Foote (February 28, 1804May 19, 1880) was a United States Senator from Mississippi and the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations from 1847 to 1852. He was a Unionist Governor of Mississippi from 1852 to ...

countered that Page had not proved substantial progress or benefits from his work. Senator Jefferson Finis Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

objected to the appropriation of government funds to one inventor, while other inventors such as Thomas Davenport went unsupported. Both the US Senate and House nixed any further funds for a Page's project.

By the 1860s, the induction coil was becoming a prominent instrument of physics research. Instrument-makers in America, Great Britain and the European continent contributed in developing the construction and operation of induction coils. Premiere among these instrument makers was Heinrich Daniel Ruhmkorff, who in 1864 received from Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

the prestigious Volta Prize The Volta Prize (French: ''prix Volta'') was originally established by Napoleon III during the Second French Empire in 1852 to honor Alessandro Volta, an Italian physicist noted for developing the electric battery.John L. Davis. Artisans and savants ...

along with a 50,000 franc award for his introduction of the induction coil. Page maintained that the devices he developed in the 1830s were not markedly different from the induction coil and that other American inventors had filled in with improvements that were better than anything made by Ruhmkorff — and alleging that Ruhmkorff had plagiarized the coil of another American instrument-maker, Edward Samuel Ritchie

Edward Samuel Ritchie (1814–1895), an American inventor and physicist, is considered to be the most innovative instrument maker in nineteenth-century America, making important contributions to both science and navigation.

Early life and career

R ...

.

A special act passed by the U.S. House and Senate, and signed by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

authorized what was later dubbed "The Page Patent". Page died a few weeks later, in May 1868. Instead of dying with him, the Page patent went on to play a major role in the politics and economics of the telegraph industry. Page's lawyer and heirs successfully argued that the patent covered the mechanisms involved in "all known forms of telegraphy". An interest in the patent was sold to the Western Union Co; together Western Union and the Page heirs reaped lucrative benefits. Page's patent secured a life 'in style' for his widow and heirs. Although he was no longer living, it figured as yet another violation, on his part, of the behavior code under the emerging professionalization of science of the day, under which science was to be conducted for its own sake, without accruing apparent political or financial gain.

Personal life

Page in 1843 became engaged to Priscilla Sewall Webster who was the younger sister of the wife of a Washington physician, Harvey Lindsly. Lindsly happened to be among Page's colleagues. Page married Priscilla in 1844 and the couple had a son who died in infancy. They then had three more sons and two daughters that grew to adulthood and outlived him. Their oldest daughter, Emelyn or Emmie, died less than a year after Page's own death. Their youngest son, Harvey Lindsly Page (1859–1934), was named for his uncle and was a famous American architect and inventor ofSan Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

.

Page's many contributions have slipped from the view of most historians with little remaining of his experimental work and notes. He suffered debt, terminal illness and isolation from the mainstream scientific community in his last years. Page published anonymously a lengthy, closely researched yet self-promoting book titled ''American Claim to Induction Coil and its electrostatic developments''. He died in Washington, D.C., on May 5, 1868. Page's wife Priscilla died August 7, 1894. Webster, 1912, p. 44

See also

* Thomas HallReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Patents

*C.G. Page, U.S. Patent 20,507, "Head Rest" *C.G. Page, U.S. Patent 76,654, "Induction Coil Apparatus and Circuit Breaker "External links

Works by Charles Grafton Page

at

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a Virtual volunteering, volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the ...

Instruments for Natural Philosophy - Daniel Davis Jr. Apparatus

{{DEFAULTSORT:Page, Charles Grafton American physicists 19th-century American inventors People associated with electricity 19th-century American people 1812 births 1868 deaths People from Salem, Massachusetts Harvard Medical School alumni Harvard College alumni