Charles Follen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

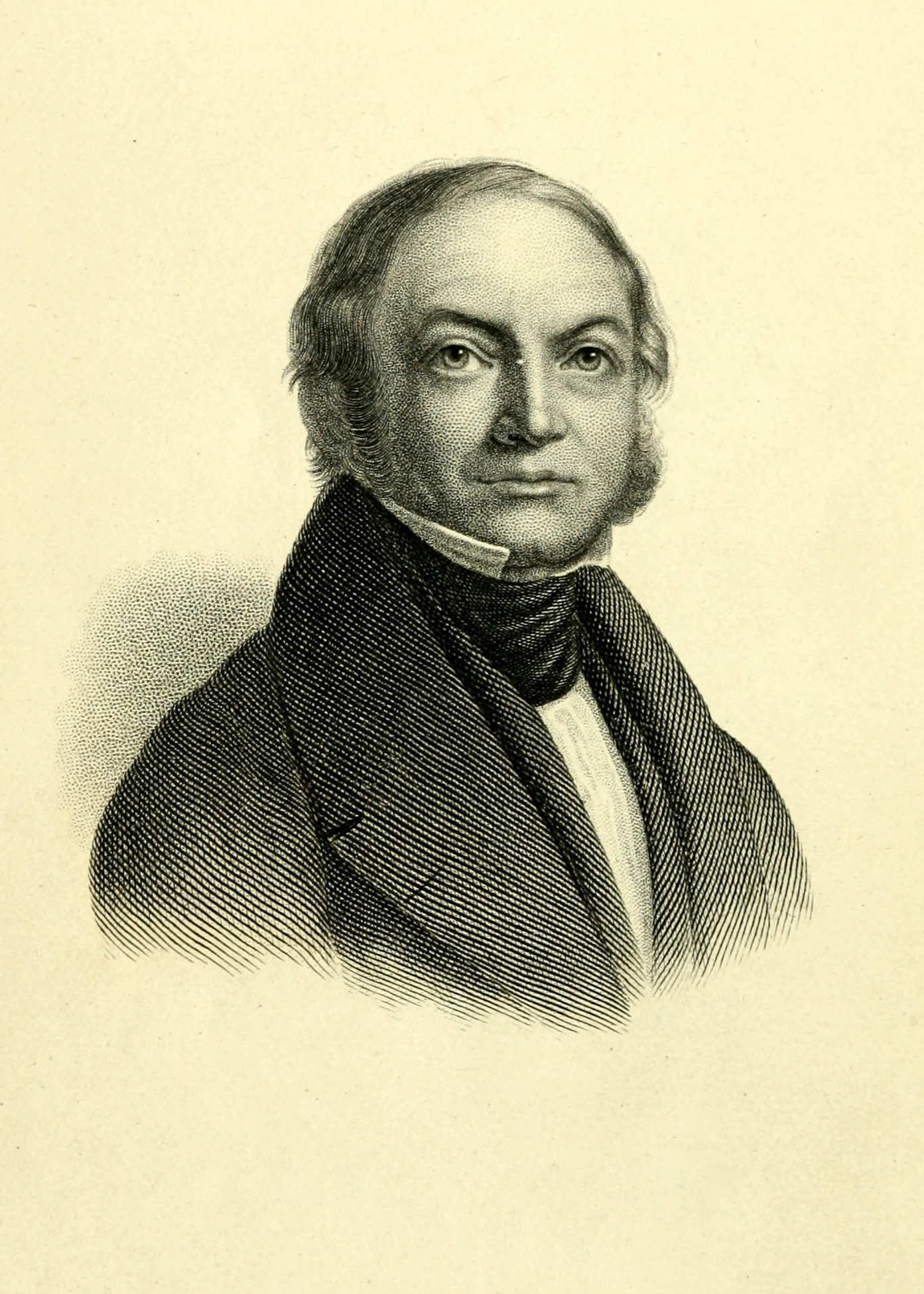

Charles (Karl) Theodor Christian Friedrich Follen (September 6, 1796 – January 13, 1840) was a

Charles (Karl) Theodor Christian Friedrich Follen (September 6, 1796 – January 13, 1840) was a

Arriving at

Arriving at

Charles Follen: Brief life of a vigorous reformer, 1796-1840

in the

Harvard Magazine

' (September–October 2002).

* * * Frank Mehring, ed. (2007)

Between Natives and Foreigners: Selected Writings of Karl/Charles Follen (1796–1840) (New Directions in German-American Studies)

'' Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers

Charles (Karl) Theodor Christian Friedrich Follen (September 6, 1796 – January 13, 1840) was a

Charles (Karl) Theodor Christian Friedrich Follen (September 6, 1796 – January 13, 1840) was a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

poet and patriot, who later moved to the United States and became the first professor of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, a Unitarian minister, and a radical abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

. He was fired by Harvard for his abolitionist statements.

Life in Europe

Karl Theodor Christian Friedrich Follen was born atRomrod

Romrod is a small town in the Vogelsbergkreis in central Hesse, Germany.

Geography

Location

Through the town flows the river Antrift.

Neighbouring communities

Romrod borders in the north on the town of Alsfeld, in the east on the community of ...

, in Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse be ...

(present-day Germany), to Christoph Follenius (1759–1833) and Rosine Follenius (1766–1799). His father was a counselor-at-law and judge in Giessen

Giessen, spelled Gießen in German (), is a town in the German state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of both the district of Giessen and the administrative region of Giessen. The population is approximately 90,000, with roughly 37,000 unive ...

, in Hesse-Darmstadt. His mother had retired to Romrod to avoid the French revolutionary troops that had occupied Giessen. He was the brother of August Ludwig Follen and Paul Follen, and the uncle of the biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize ...

Carl Vogt

August Christoph Carl Vogt (; 5 July 18175 May 1895) was a German scientist, philosopher, popularizer of science, and politician who emigrated to Switzerland. Vogt published a number of notable works on zoology, geology and physiology. All h ...

.

He was educated at the preparatory school at Giessen, where he distinguished himself for proficiency in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, French, and Italian. At the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von ...

to study theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

. In 1814 he and his brother August Ludwig went to fight in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

as Hessian volunteers; however, a few weeks after enlisting, his military career was cut short by an acute attack of typhus fever, which seemed for a time to have completely destroyed his memory. After his recovery he returned to the university and began studying law, and in 1818 was awarded a doctorate in civil and ecclesiastical law. He then established himself as ''Privatdocent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

'' of civil law at Giessen, while simultaneously studying the practice of law in his father's court. As a student, Follen joined the Giessen Burschenschaft

A Burschenschaft (; sometimes abbreviated in the German ''Burschenschaft'' jargon; plural: ) is one of the traditional (student associations) of Germany, Austria, and Chile (the latter due to German cultural influence).

Burschenschaften were fo ...

, whose members were pledged to republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

an ideals. Though he did not attend himself, Follen was a major organizer of the first Wartburg festival of 1817.This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired ...

:

Early in the fall of 1818, he undertook the cause of several hundred communities in Upper Hesse

The term Upper Hesse (german: Provinz Oberhessen) originally referred to the southern possessions of the Landgraviate of Hesse, which were initially geographically separated from the more northerly Lower Hesse by the .

Later, it became the name o ...

in opposition to a government measure directed at the last remnant of their political independence, and drew up a petition to the grand duke on their behalf. It was printed and widely circulated, and aroused public indignation to such a pitch that the obnoxious measure was repealed. However, the opposition of the influential men whose plans were thereby thwarted precluded any thought of a career in Follen's home town. He became a ''Privatdozent'' at the University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The ...

in October 1818.

At Jena, he wrote political essays, poems, and patriotic songs. His essays and speeches advocated violence and tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good,

and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in the Classical period. Often, the term tyr ...

in defense of freedom; this, and his friendship with Karl Ludwig Sand

Karl Ludwig Sand (Wunsiedel, Upper Franconia (then in Prussia), 5 October 1795 – Mannheim, 20 May 1820) was a German university student and member of a liberal Burschenschaft (student association). He was executed in 1820 for the murder of the ...

brought him under suspicion as an accomplice

Under the English common law, an accomplice is a person who actively participates in the commission of a crime, even if they take no part in the actual criminal offense. For example, in a bank robbery, the person who points the gun at the telle ...

in Sand's 1819 assassination of the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

diplomat and dramatist August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue (; – ) was a German dramatist and writer who also worked as a consul in Russia and Germany.

In 1817, one of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl L ...

. Follen destroyed letters linking him with Sand. He was arrested, but finally acquitted due to lack of evidence. His dismissal from the university and continuing lack of opportunity prompted him to move to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. There he met Charles Comte, the son-in-law of Jean Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

and founder of the '' Censeur'', a publication which he defended until he chose exile in Switzerland over imprisonment in France. He also became acquainted with Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, who was then planning his trip to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. Follen came under suspicion again after the political assassination of Charles Ferdinand, duc de Berry

Charles Ferdinand d'Artois, Duke of Berry (24 January 1778 – 14 February 1820) was the third child and younger son of Charles X, King of France, (whom he predeceased) by his wife Maria Theresa of Savoy. In June 1832, two years after the overthr ...

in 1820, and fled from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

In Switzerland, he taught Latin and history for a while at the canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ente ...

al school of the Grisons

The Grisons () or Graubünden,Names include:

*german: (Kanton) Graubünden ;

* Romansh:

** rm, label= Sursilvan, (Cantun) Grischun

** rm, label= Vallader, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label= Puter, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label= Surmiran, (Ca ...

at Coire. His lectures, with their Unitarian tendencies, offended some of the Calvinistic

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

ministers in the district, so Follen requested and obtained a dismissal, with a testimonial to his ability, learning, and worth. He then became a lecturer on law and metaphysics at the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis'', German: ''Universität Basel'') is a university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest surviving universiti ...

. At Basel, he made the acquaintance of the theologian Wilhelm de Wette Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (12 January 1780 – 16 June 1849) was a German theologian and biblical scholar.

Life and education

Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette was born 12 January 1780 in Ulla (now part of the municipality of Nohra), Thuri ...

and his stepson Karl Beck. Both Follen and Charles Comte were forced to leave Switzerland. In Follen's case, demands were made by the German government for his surrender as a revolutionist. These were twice refused, but after a third (more threatening) demand, Basel yielded, passing a resolution for Follen's arrest. In 1824 Follen and Beck left Switzerland for the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

via Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

, France.

Life in the United States

Arriving at

Arriving at New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 1824, Follen anglicized his name to "Charles." Lafayette was then visiting the United States and sought to interest some people of influence in the two refugees, who had moved from New York City and settled in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

. Among those Lafayette contacted were Peter Stephen Du Ponceau

Peter Stephen Du Ponceau (born Pierre-Étienne du Ponceau, June 3, 1760 – April 1, 1844) was a French-American linguist, philosopher, and jurist. After emigrating to the colonies in 1777, he served in the American Revolutionary War. Afterward ...

, a prominent lawyer, and George Ticknor

George Ticknor (August 1, 1791 – January 26, 1871) was an American academician and Hispanist, specializing in the subject areas of languages and literature. He is known for his scholarly work on the history and criticism of Spanish literature.

...

, a Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

professor. Ticknor in turn interested George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts and at the national and internati ...

.

With the help of these sympathetic people, the refugees established themselves in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

society. Beck quickly secured a position at Bancroft's Round Hill School The Round Hill School for Boys was a short-lived experimental school in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was founded by George Bancroft and Joseph Cogswell in 1823. Though it failed as a viable venture — it closed in 1834 — it was an early effort ...

in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence and Leeds) was 29,571.

Northampton is known as an a ...

, in February 1825. Follen continued to study the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

and law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

in Philadelphia, and in November 1825 took up an offer from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

to be an instructor in German. In 1828 he became an instructor of ethics and ecclesiastical history at Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the academic study of religion or for leadership roles in religion, gov ...

, having in the meantime been admitted as a candidate for the ministry. In 1830 he was appointed professor of German literature

German literature () comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a less ...

at Harvard. He became friendly with the New England Transcendentalists, and helped introduce them to German Romantic thought. In 1828, he married Eliza Lee Cabot, the daughter of one Boston's most prominent families.

Follen also gave demonstrations of the new discipline of gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, s ...

, made popular by "Father Jahn". In 1826, at the request of a group in Boston, he established and equipped the first gym

A gymnasium, also known as a gym, is an indoor location for athletics. The word is derived from the ancient Greek term " gymnasium". They are commonly found in athletic and fitness centres, and as activity and learning spaces in educational i ...

nasium there and became its superintendent. Follen resigned this position in 1827, and the responsibilities were taken over by Francis Lieber

Francis Lieber (March 18, 1798 or 1800 – October 2, 1872), known as Franz Lieber in Germany, was a German-American jurist, gymnast and political philosopher. He edited an ''Encyclopaedia Americana''. He was the author of the Lieber Code duri ...

. With the assistance of Beck, Follen established the first college gymnasium in the United States at Harvard in 1826.

The Follens had a house built on the corner of Follen Street in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. Their family Christmas tree

A Christmas tree is a decorated tree, usually an evergreen conifer, such as a spruce, pine or fir, or an artificial tree of similar appearance, associated with the celebration of Christmas. The custom was further developed in early modern ...

attracted the attention of the English writer Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (; 12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist, focusing on race relations within much of her published material.Michael R. Hill (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretic ...

during her long visit to the United States, and the Follens have been claimed by some as the first to introduce the German custom of decorated Christmas tree to the United States. (Although the claim is one of several competing claims for the introduction of the custom to the United States, they, together with Martineau, were certainly early and prominent popularizers of the custom.) His brother Paul Follen emigrated in 1834 to the United States, settling in Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

.

In 1835, Charles Follen lost his professorship at Harvard due to his outspoken abolitionist beliefs and his conflict with University President Josiah Quincy Josiah Quincy may refer to:

* Josiah Quincy I (1710–1784), American merchant, planter, soldier, and politician

*Josiah Quincy II (1744–1775), American lawyer and patriot

*Josiah Quincy III (1772–1864), American educator and political figure, ...

's strict disciplinary measures for undergraduates. A close friend and associate of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

, Follen's outspoken opposition to slavery had incurred the hostility and scorn of the public press. Like most of the early radical abolitionists, Follen at the beginning was censured by public opinion even in the locality which later became the centre of the abolition spirit. The good beginning that had been made in the study of the German language in New England was totally discontinued. The cause of German literature

German literature () comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a less ...

had still a friend in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

, who in 1838 began his lectures on Johann von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

's ''Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroa ...

''.Faust (1909), v. 2, pp. 216-217.

Follen's friendship with the prominent Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing

William Ellery Channing (April 7, 1780 – October 2, 1842) was the foremost Unitarian preacher in the United States in the early nineteenth century and, along with Andrews Norton (1786–1853), one of Unitarianism's leading theologians. Channi ...

drew him to the Unitarian Church. He was ordained as a minister in 1836. He had been called to the pulpit of the Second Congregational Society in Lexington, Massachusetts

Lexington is a suburban town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is 10 miles (16 km) from Downtown Boston. The population was 34,454 as of the 2020 census. The area was originally inhabited by Native Americans, and was fir ...

(now Follen Church Society-Unitarian Universalist) in 1835, but the community was unable to pay him sufficiently to support his family. Follen took other employment; Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

supplied the pulpit from 1836 to 1838 at the church. In 1838 Follen became the minister of his own congregation in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, now All Souls, but lost the position within the year due to conflicts over his radical anti-slavery views. He considered returning to Germany, but returned in 1839 to the congregation in East Lexington, Massachusetts. He had designed its unique octagonal building, for which ground was broken on July 4, 1839. Follen's octagonal building is still standing, and is the oldest church structure in Lexington. In his prayer at the groundbreaking for the building, Follen declared the mission of his church:

aythis church never be desecrated by intolerance, or bigotry, or party spirit; more especially its doors might never be closed against any one, who would plead in it the cause of oppressed humanity; within its walls all unjust and cruel distinctions might cease, andFollen broke off a lecture tour in New York and took the Steamship ''Lexington'' to Boston for the dedication of his new church. Follen died en route when his steamer caught fire and sank in a storm in thehere Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to: Software * Here Technologies, a mapping company * Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here Television * Here TV (formerly "here!"), a ...all men might meet as brethren.

Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is a marine sound and tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies predominantly between the U.S. state of Connecticut to the north and Long Island in New York to the south. From west to east, the sound stretches from the Eas ...

. Due to Follen's abolitionist positions, his friends were unable to find any church in Boston willing to hold a memorial service on his behalf. Rev. Samuel J. May was finally able to hold a memorial service for Follen in March 1840 at the Marlborough Chapel. This was an unaffiliated hall attached to the Marlborough Hotel on the corner of Washington Street and Franklin Street in Boston.

Works

* ''Psychology'' (1836) * ''Essay on Religion and the Church'' (1836) * In 1841, Follen's widowEliza

ELIZA is an early natural language processing computer program created from 1964 to 1966 at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory by Joseph Weizenbaum. Created to demonstrate the superficiality of communication between humans and machines, ...

, a well-known author in her own right, published a five-volume collection containing his sermons and lectures, his unfinished sketch of a work on psychology and a biography she wrote.

Notes

References

* Thomas S. HansenCharles Follen: Brief life of a vigorous reformer, 1796-1840

in the

Harvard Magazine

' (September–October 2002).

* * * Frank Mehring, ed. (2007)

Between Natives and Foreigners: Selected Writings of Karl/Charles Follen (1796–1840) (New Directions in German-American Studies)

'' Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Follen, Charles 1796 births 1840 deaths 19th-century American writers 19th-century German writers 19th-century German male writers 19th-century poets Abolitionists from Boston American gymnasts American Unitarians Deaths due to ship fires Deaths from fire in the United States German emigrants to the United States German male poets Harvard University faculty People from Vogelsbergkreis People from the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt University of Giessen alumni