Censorship in the United States involves the suppression of speech or public communication and raises issues of

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogn ...

, which is protected by the

First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

to the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. Interpretation of this

fundamental freedom has varied since its enshrinement. Traditionally, the First Amendment was regarded as applying only to the Federal government, leaving the states and local communities free to censor or not. As the applicability of

states rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and t ...

in lawmaking vis-a-vis citizens' national rights began to wain in the wake of the Civil War, censorship by any level of government eventually came under scrutiny, but not without resistance. For example, in recent decades, censorial restraints increased during the 1950s period of widespread

anti-communist sentiment, as exemplified by the hearings of the

House Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disl ...

. In ''

Miller v. California

''Miller v. California'', 413 U.S. 15 (1973), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court modifying its definition of obscenity from that of "utterly without socially redeeming value" to that which lacks "serious literary, artistic, poli ...

'' (1973), the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

found that the First Amendment's freedom of speech does not apply to

obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be us ...

, which can, therefore, be censored. While certain forms of

hate speech

Hate speech is defined by the '' Cambridge Dictionary'' as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation". Hate speech is "usually thou ...

are legal so long as they do not turn to action or incite others to commit illegal acts, more severe forms have led to people or groups (such as the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and C ...

) being denied marching permits or the

Westboro Baptist Church

The Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) is a small American, unaffiliated Primitive Baptist church in Topeka, Kansas, founded in 1955 by pastor Fred Phelps. Labeled a hate group, WBC is known for engaging in homophobic and anti-American pickets ...

being sued, although the initial adverse ruling against the latter was later overturned on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court case ''

Snyder v. Phelps

''Snyder v. Phelps'', 562 U.S. 443 (2011), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court ruling that speech on a matter of public concern, on a public street, cannot be the basis of liability for a tort of emotional distress, even in the circum ...

''.

The First Amendment protects against censorship imposed by law, but does not protect against

corporate censorship

Corporate censorship is censorship by corporations. It is when a spokesperson, employer, or business associate sanctions a speaker's speech by threat of monetary loss, employment loss, or loss of access to the marketplace. It is present in many ...

, the restraint of speech of spokespersons, employees, or business associates by threatening monetary loss, loss of employment, or loss of access to the marketplace.

Legal expenses can be a significant hidden restraint where there is fear of suit for

libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

. Many people in the United States are in favor of restricting censorship by corporations, citing a

slippery slope

A slippery slope argument (SSA), in logic, critical thinking, political rhetoric, and caselaw, is an argument in which a party asserts that a relatively small first step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant (usuall ...

that if corporations do not follow the

Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

, the government will be influenced.

Analysts from

Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB; french: Reporters sans frontières; RSF) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organization with the stated aim of safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its advocacy as fou ...

ranked the United States 42nd in the world out of 180 countries in their 2022

Press Freedom Index

The Press Freedom Index is an annual ranking of countries compiled and published by Reporters Without Borders since 2002 based upon the organisation's own assessment of the countries' press freedom records in the previous year. It intends to re ...

. Certain forms of speech, such as

obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be us ...

and

defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, are restricted in

communications media by the government or by the industry on its own.

History

Colonial government

Censorship came to

British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 16 ...

with the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'' "when the governor of

Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known as ...

,

William Bradford learned

n 1629

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

ref name="ReferenceA">John P. McWilliams, "Thomas Morton: Phoenix of New England Memory" in ''New England's Crises and Cultural Memory: Literature, Politics, History, Religion, 1620–1860''. Cambridge University Press, , pp. 44–73. that

Thomas Morton of

Merrymount, in addition to his other misdeed, had 'composed sundry rhymes and verses, some tending to lasciviousness' the only solution was to send a military expedition to break up Morton's high-living."

A celebrated legal case in 1734–1735 involved

John Peter Zenger

John Peter Zenger (October 26, 1697 – July 28, 1746) was a German printer and journalist in New York City. Zenger printed '' The New York Weekly Journal''. He was accused of libel in 1734 by William Cosby, the royal governor of New York, but ...

, a New York newspaper printer who regularly published material critical of the corrupt Governor of New York,

William Cosby

Brigadier-General William Cosby (1690–1736) was an Irish soldier who served as the British colonial governor of New York from 1732 to 1736. During his short term, Cosby was portrayed as one of the most oppressive governors in the Thirteen Col ...

. He was jailed eight months before being tried for

seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection a ...

.

Andrew Hamilton defended him and was made famous for his speech, ending in "nature and the laws of our country have given us a right to liberty of both exposing and opposing arbitrary power ... by speaking and writing the truth."

Zenger's lawyers attempted to establish the precedent that a statement, even if defamatory, is not libelous if it can be proved. While the judge ruled against his arguments, Hamilton urged

jury nullification

Jury nullification (US/UK), jury equity (UK), or a perverse verdict (UK) occurs when the jury in a criminal trial gives a not guilty verdict despite a defendant having clearly broken the law. The jury's reasons may include the belief that the ...

in the cause of liberty and won a not guilty verdict. The Zenger case paved the way for freedom of the press to be adopted in the U.S. Constitution. As Founding Father

Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the U ...

stated, "The trial of Zenger in 1735 was the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America."

19th century

Beginning in the 1830s and until the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the US

Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

refused to allow mailmen to carry

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

pamphlets to the South.

On March 3, 1873, significant censorship legislation, the ''

Comstock Law

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression o ...

'', was passed by the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

under the

Grant administration

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The ...

; an Act for the "Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use." The Act criminalized usage of the

U.S. Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the Federal government of the Uni ...

to send any of the following items:

erotica

Erotica is literature or art that deals substantively with subject matter that is erotic, sexually stimulating or sexually arousing. Some critics regard pornography as a type of erotica, but many consider it to be different. Erotic art may use a ...

;

contraceptive

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth cont ...

s;

abortifacient

An abortifacient ("that which will cause a miscarriage" from Latin: '' abortus'' "miscarriage" and '' faciens'' "making") is a substance that induces abortion. This is a nonspecific term which may refer to any number of substances or medications, ...

s;

sex toy

A sex toy is an object or device that is primarily used to facilitate human sexual pleasure, such as a dildo, artificial vagina or vibrator. Many popular sex toys are designed to resemble human genitals, and may be vibrating or non-vibrati ...

s; personal letters alluding to any sexual content or information; or any information regarding the above items.

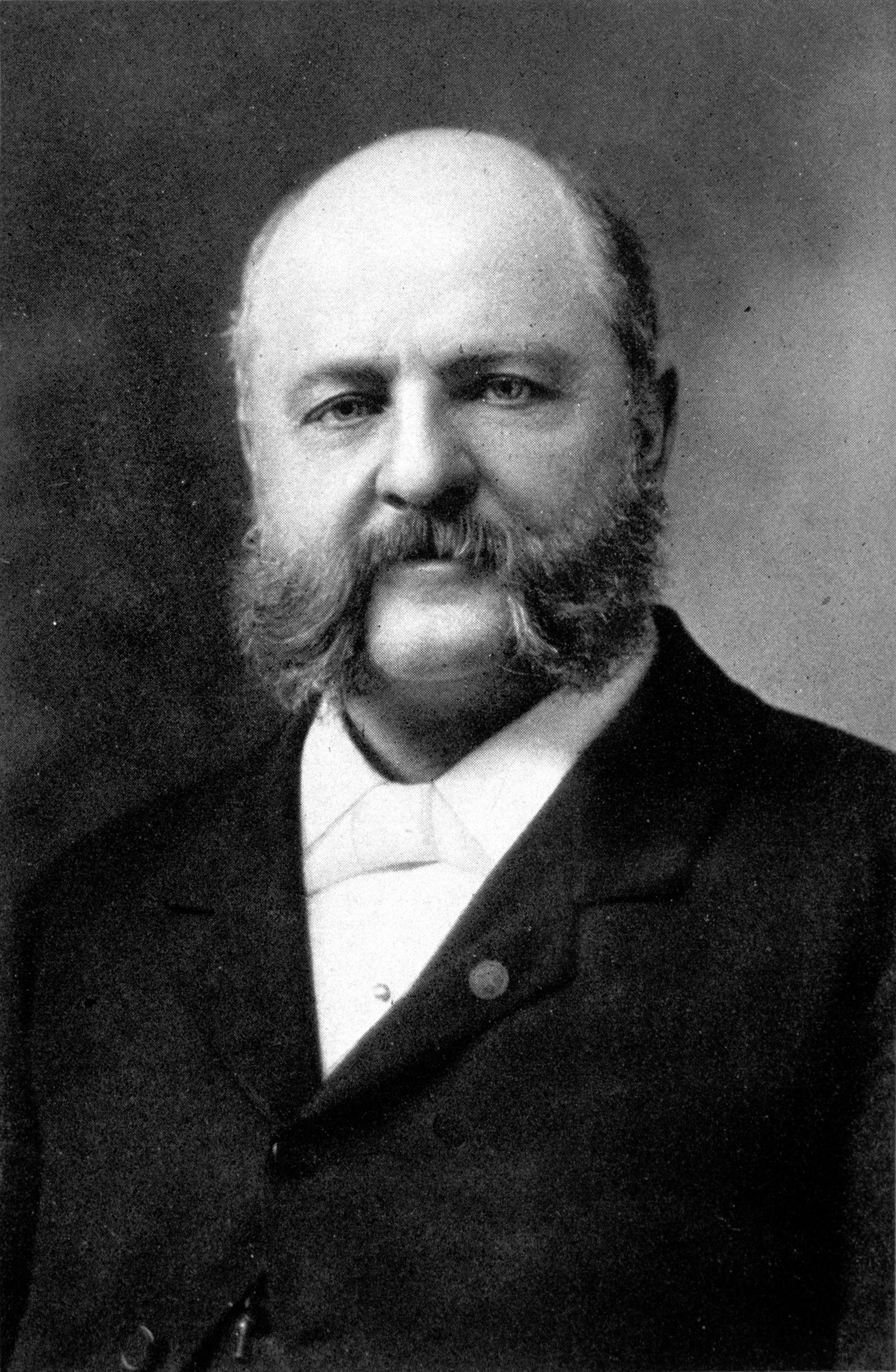

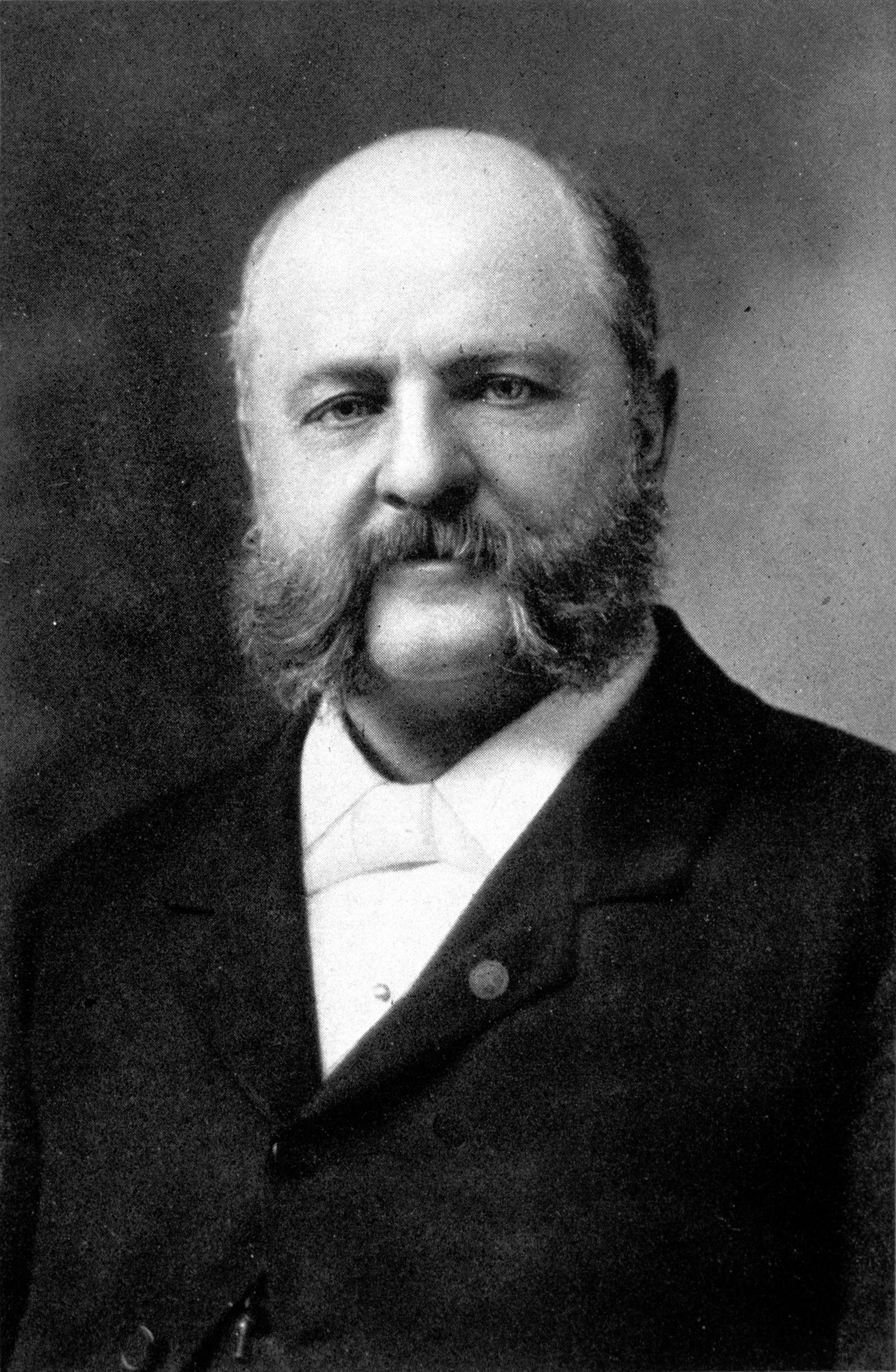

The law was named after

Anthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock (March 7, 1844 – September 21, 1915) was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector, and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), who was dedicated to upholding Christian morality. He o ...

, U.S. Postal Inspector and founder of the

New York Society for the Suppression of Vice

The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV or SSV) was an institution dedicated to supervising the morality of the public, founded in 1873. Its specific mission was to monitor compliance with state laws and work with the courts and di ...

, who was known for his crusades against sexual expression and education. Comstock's name became a byword for censorship, inspiring terms such as "comstockery" and "comstockism" to refer to such activities. He opposed the distribution of information about abortion and birth control, and he is credited with having destroyed 15 tons of books, almost 4,000,000 pictures and 284,000 pounds of printing plates for making "objectionable" books.

20th century

Wilson administration

The

Sedition Act of 1918

The Sedition Act of 1918 () was an Act of the United States Congress that extended the Espionage Act of 1917 to cover a broader range of offenses, notably speech and the expression of opinion that cast the government or the war effort in a ne ...

() was an Act of the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

that extended the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (Wa ...

to cover a broader range of offenses, notably speech and the expression of opinion that cast the government or the war effort in a negative light or interfered with the sale of government bonds.

It forbade the use of "disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language" about the United States government, its flag, or its armed forces or that caused others to view the American government or its institutions with contempt. Those convicted under the act generally received sentences of imprisonment for five to 20 years. The act also allowed the

Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

to refuse to deliver mail that met those same standards for punishable speech or opinion. It applied only to times "when the United States is in war." The U.S. was in a

declared a state of war at the time of passage, the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The law was repealed on December 13, 1920.

[Stone, 230]

Though the legislation enacted in 1918 is commonly called the Sedition Act, it was actually a set of amendments to the Espionage Act.

Franklin D. Roosevelt administration

The "Radio Priest"

Charles Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of the ...

started broadcasting in 1926 and entertained an audience of millions in the 1930s, but became increasingly anti-democratic, antisemitic, and sympathetic to

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Coughlin was denied a license when the government first started requiring them for broadcasters, forcing him to purchase air time from others. He was forced off the air completely when the private

National Association of Broadcasters

The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) is a trade association and lobby group representing the interests of commercial and non-commercial over-the-air radio and television broadcasters in the United States. The NAB represents more tha ...

adopted rules banning "spokesmen of controversial public issues". The mailing permit of Coughlin's newspaper ''

Social Justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals f ...

'' was suspended under the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (Wa ...

, confining delivery to the local Boston area. The paper was shut down after the government persuaded Coughlin's bishop to stop his political activities entirely.

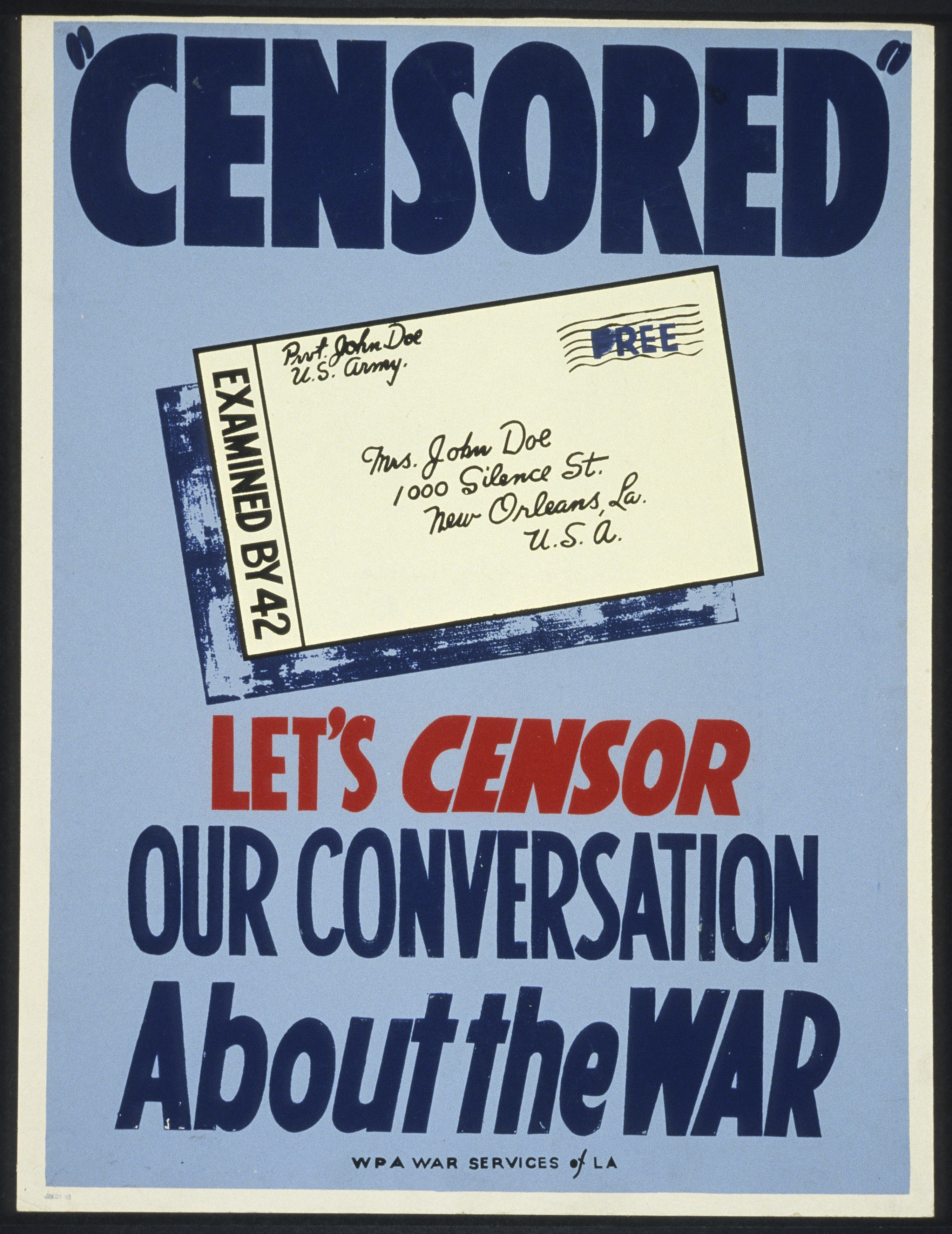

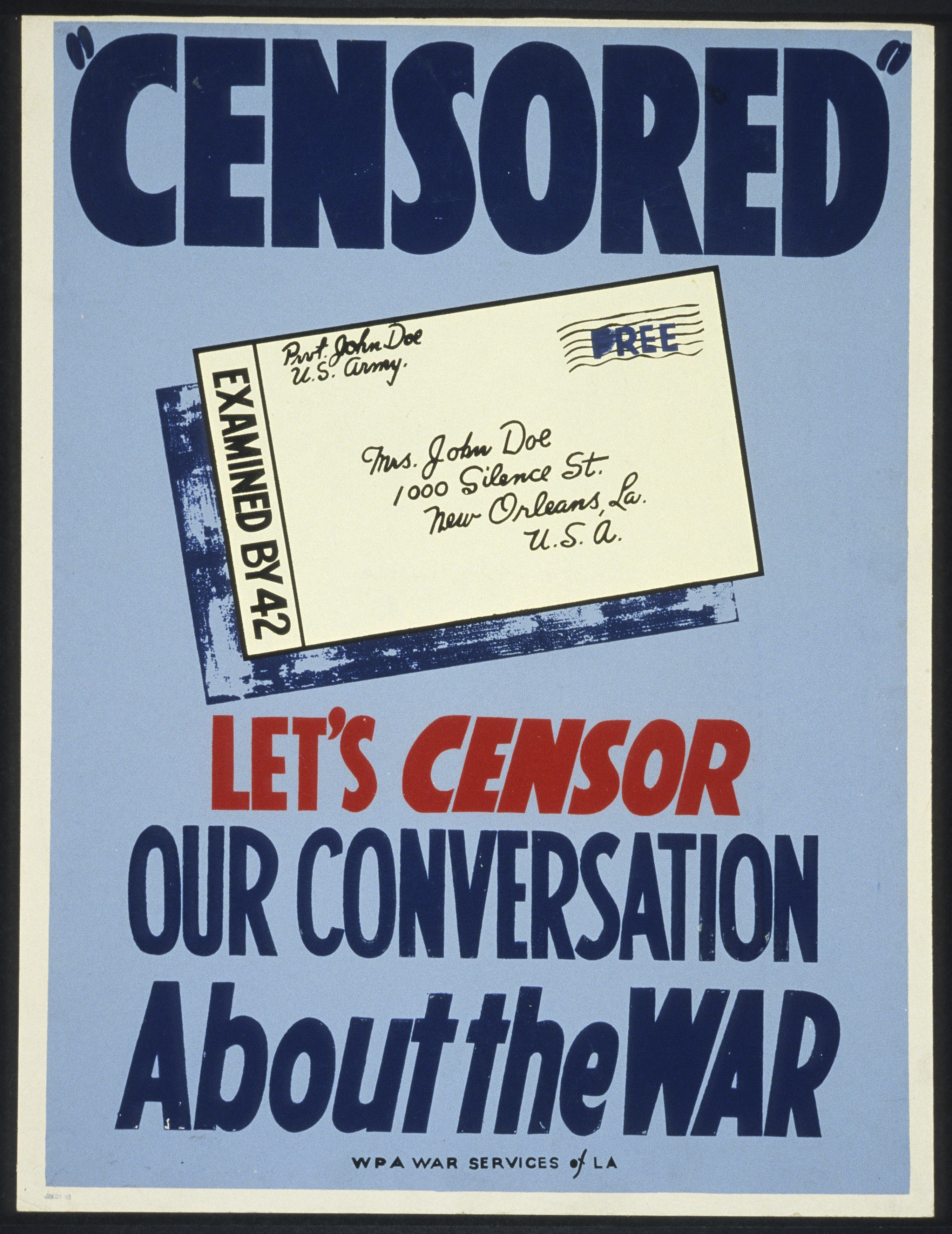

The

Office of Censorship, an emergency wartime agency, heavily censored reporting during

World War II. During

World War I, and to a greater extent during

World War II,

war correspondents accompanied military forces, and their reports were subject to advance censorship to preserve military secrets. The extent of such censorship was not generally challenged, and no major court case arose from this issue, and even the Supreme Court found it constitutional on the grounds that it "protected free speech from tyranny."

On December 19, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8985, which established the Office of Censorship and conferred on its director the power to censor international communications in "his absolute discretion."

Byron Price was selected as the Director of Censorship. However, censorship was not limited to reporting;

postal censorship

Postal censorship is the inspection or examination of mail, most often by governments. It can include opening, reading and total or selective obliteration of letters and their contents, as well as covers, postcards, parcels and other postal p ...

also took place. "Every letter that crossed international or U.S. territorial borders from December 1941 to August 1945 was subject to being opened and scoured for details."

Truman administration

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term orig ...

is the term describing a period of intense anti-Communist suspicion in the United States that lasted roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1950s when the

Smith Act trials of communist party leaders

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of US federal government prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. Leaders of the ...

occurred. The Alien Registration Act or

Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

of 1940 made it a criminal offense for anyone to "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the ... desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association." Hundreds of Communists were prosecuted under this law between 1941 and 1957. Eleven leaders of the Communist Party were charged and convicted under the Smith Act in 1949. Ten defendants were given sentences of five years and the eleventh was sentenced to three years. All of the defense attorneys were cited for

contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

and were also given prison sentences. In 1951, twenty-three other leaders of the party were indicted including

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Uni ...

, a founding member of the

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

, who was removed from the board of the

ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

in 1940 for membership in a political organization which supported

totalitarian dictatorship. By 1957 over 140 leaders and members of the Communist Party had been charged under the law. In 1952, the

Immigration and Nationality, or McCarran-Walter, Act was passed. This law allowed the government to deport immigrants or naturalized citizens engaged in subversive activities and also to bar suspected subversives from entering the country.

Eisenhower administration

The

Communist Control Act of 1954 was passed with overwhelming support in both houses of Congress after very little debate. Jointly drafted by Republican

John Marshall Butler and Democrat

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing M ...

, the law was an extension of the Internal Security Act of 1950, and sought to outlaw the Communist Party by declaring that the party, as well as "Communist-Infiltrated Organizations" were "not entitled to any of the rights, privileges, and immunities attendant upon legal bodies."

John W. Powell

John William Powell (July 3, 1919 – December 15, 2008) was a journalist and small business proprietor who edited the ''China Weekly Review'', an English-language journal first published by his father, John B. Powell in Shanghai.

John W. Pow ...

, a journalist who reported the allegations that US was carrying out

germ warfare in the Korean War

Allegations that the United States military used biological weapons in the Korean War (June 1950 – July 1953) were raised by the governments of People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and North Korea. The claims were first raised ...

in an English-language journal in

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, the "China Monthly Review", was indicted with 13 counts of

sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

, along with his 2 editors. All defendants were acquitted of all charges over the next six years, but Powell was blackballed from the journalism industry for the rest of his life.

The book-burning of

Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( , ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian doctor of medicine and a psychoanalyst, along with being a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several influential books, mos ...

's work took place between 1956 and 1960. It has been cited as the worst example of censorship in the United States. ''The Guardian'' called it "the only federally sanctioned book burning on American soil." He died in prison of heart failure just over a year later, days before he was due to apply for parole.

[Sharaf 1994, p.&nbs]

477

In 1960, ''The China Lobby in American Politics'', by scholar Ross Y. Koen, was suppressed by the

State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

, the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

and the

Federal Bureau of Narcotics at the behest of the

Chinese Nationalist Party

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Taiw ...

– at that time the ruling party of the

martial dictatorship in

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a Country, country in East Asia, at the junction of the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) to the n ...

. The book largely concerned the influence of the

China lobby

In American politics, the China lobby consisted of advocacy groups calling for American support for the Republic of China during the period from the 1930s until US recognition of the People's Republic of China in 1979, and then calling for clos ...

in the US congress and the executive branch of the government. It also detailed heroin trafficking by the Chinese Nationalist Party, which was later corroborated by other scholars. After 4000 copies of the book had been printed, at the intervention of the State Department the publisher recalled the book and discontinued publication. Some copies of the book nevertheless found their way into rare book repositories at some universities. According to

Richard C. Kagan, right-wing groups stole many remaining copies of the book from libraries. The book was reprinted in 1974 after other scholars had shown Koen's findings to be accurate.

Nixon administration

In later conflicts, the degree to which war reporting was subject to censorship varied, and in some cases, it has been alleged that the censorship was as much political as military in purpose. This was particularly true during the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietna ...

. The executive branch of the federal government attempted to prevent ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' from publishing the top-secret

Pentagon Papers

The ''Pentagon Papers'', officially titled ''Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force'', is a United States Department of Defense history of the United States' political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 ...

during the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietna ...

, warning that doing so would be considered an act of treason under the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (Wa ...

. The newspaper prevailed in the famous ''

New York Times Co. v. United States

''New York Times Co. v. United States'', 403 U.S. 713 (1971), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States on the First Amendment right of Freedom of the Press. The ruling made it possible for ''The New York Times'' and ''The ...

'' case.

Clinton administration

The

Child Online Protection Act

The Child Online Protection Act (COPA) was a law in the United States of America, passed in 1998 with the declared purpose of restricting access by minors to any material defined as harmful to such minors on the Internet. The law, however, neve ...

, passed in 1998 and signed by

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, was criticized and legally challenged by civil liberties groups, claiming that it "reduces the Internet to what is fit for a six-year-old. Through legal actions and permanent injunction, the act never took effect.

21st century

George W. Bush administration

Press censorship issues arose again during the administration of President

George W. Bush during the

2003 Invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Ba'athist Iraq, Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one mont ...

. Journalists who were embedded within the armed forces had to accept certain terms and restrictions on what they were reporting and additionally were required to make their reports available to media operations staff prior to publication. This process was put in place to not compromise security nor endanger troops by revealing exact locations.

President Bush's administration also attempted to censor results of climate studies, "nearly half of 1,600 government scientists at seven agencies ranging from NASA to the EPA had been warned against using terms like 'global warming' in reports or speeches, throughout Bush's eight-year presidency."

Obama administration

In July 2014, the

Society of Professional Journalists

The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), formerly known as Sigma Delta Chi, is the oldest organization representing journalists in the United States. It was established on April 17, 1909, at DePauw University,2009 SPJ Annual Report, letter ...

published an open letter signed by 38 journalist organizations to

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

, criticizing efforts to "stifle or block" coverage, despite his

2008 campaign promises to provide transparency. The letter cited several examples in which the administration blocked reporters from speaking directly to specific staff without obtaining prior approval from the head of their department. Obama's use of the

Espionage Act was criticized as aggressive by

CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by t ...

journalist

Jake Tapper

Jacob Paul Tapper (born March 12, 1969) is an American journalist, author, and cartoonist. He is the lead Washington anchor for CNN, hosts the weekday television news show '' The Lead with Jake Tapper'', and co-hosts the Sunday morning public af ...

. Tapper would later clarify that he was not implying such use was towards actual

whistleblowers

A whistleblower (also written as whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person, often an employee, who reveals information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe or fraudulent. Whi ...

.

Trump administration

Following the election of former president

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

, his administration pursued means of preventing federal staff from speaking publicly, with the

American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific respon ...

, "the largest scientific society in the world", warning of possible "censorship and intimidation" of the American scientific community. The Trump administration ordered the

Environmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scal ...

to scrub climate change information from their website, instructed that all studies by EPA and the

United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

be reviewed by political appointees before publication, and in some cases issued ''de facto''

gag order

A gag order (also known as a gagging order or suppression order) is an order, typically a legal order by a court or government, restricting information or comment from being made public or passed onto any unauthorized third party. The phrase may ...

s to agencies who conduct research. The White House had also denied access to a select group of media outlets including ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'',

CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by t ...

,

BBC and ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' during a

press gaggle A press gaggle (as distinct from a press conference or press briefing) is an informal briefing by the White House Press Secretary which (as used by press secretaries for the George W. Bush administration) is on the record, but disallows videograp ...

while allowing right-wing outlets and blogs to participate, with the

National Press Club

Organizations

A press club is an organization for journalists and others professionally engaged in the production and dissemination of news. A press club whose membership is defined by the press of a given country may be known as a National Press ...

describing the move as "unconstitutional censorship."

In 2017, Trump suggested challenging NBC and other TV news networks' network licenses on the grounds of allegedly propagating "fake news." On October 11, 2017, Trump posted a tweet saying, "With all of the Fake News coming out of NBC and the Networks, at what point is it appropriate to challenge their License? Bad for country!"

In December 2017, ''The Washington Post'' said that the Trump administration had potentially banned the use of certain words by the

Centers for Disease Control

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgi ...

in its written

budget proposal for FY2018. The Director of the CDC,

Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, refuted this in a statement saying, "I want to assure you there are no banned words at CDC. We will continue to talk about all our important public health programs."

Some conservative speakers and media personalities, such as

Tucker Carlson

Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson (born May 16, 1969) is an American television host, conservative political commentator and writer who has hosted the nightly political talk show ''Tucker Carlson Tonight'' on Fox News since 2016.

Carlson began ...

and

Sean Hannity

Sean Patrick Hannity (born December 30, 1961) is an American talk show host, conservative political commentator, and author. He is the host of '' The Sean Hannity Show'', a nationally syndicated talk radio show, and has also hosted a comment ...

, have said that former President Trump has been the target of social media censorship, as well as alleged censorship by privately owned social media companies

Facebook

Facebook is an online social media and social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with fellow Harvard College students and roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin Mosk ...

and

Twitter

Twitter is an online social media and social networking service owned and operated by American company Twitter, Inc., on which users post and interact with 280-character-long messages known as "tweets". Registered users can post, like, and ...

of conservative talking points. Many prominent conservative political figures have claimed that social media sites such as Twitter removed posts with conservative leanings, but these sites have claimed this is due to a removal of hateful and inflammatory rhetoric and misinformation.

On January 8, 2021, two days after the

January 6th attack on the

U.S. Capitol by a mob of Trump supporters, the official Twitter account of Trump was permanently banned by Twitter. Twitter, in an official statement, announced the reasons, saying "After close review of recent Tweets from the @realDonaldTrump account and the context around them — specifically how they are being received and interpreted on and off Twitter — we have permanently suspended the account due to the risk of further incitement of violence." The riot at the United States Capitol left 1 rioter dead by gunshot while 4 others (including 1 Capitol officer) died due to medical complications following the event. Twitter also purged more than 70,000 other far-right accounts, linked to the conspiracy theory

Q-Anon. Following this, many conservative speakers and politicians claimed the President was the target of organized social media censorship. In the

Second Impeachment of Donald Trump

Donald Trump, the 45th president of the United States, was impeached for the second time on January 13, 2021, one week before his term expired. It was the fourth impeachment of a U.S. president, and the second for Trump after his first imp ...

, his social media activity was presented as evidence by impeachment managers.

Medium

Art

A widely publicized case of prosecuting alleged obscenity occurred in 1990 when the

Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati agreed to hold an art exhibition featuring the work of photographer

Robert Mapplethorpe

Robert Michael Mapplethorpe (; November 4, 1946 – March 9, 1989) was an American photographer, best known for his black-and-white photographs. His work featured an array of subjects, including celebrity portraits, male and female nudes, self-p ...

. His work included several artistic nude photographs of males and was deemed offensive by some for this reason. This resulted in the prosecution of the CAC director, Dennis Barrie who was later acquitted.

Broadcasting

The

Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains jurisdi ...

(FCC) regulates "indecent"

free-to-air

Free-to-air (FTA) services are television (TV) and radio services broadcast in unencrypted form, allowing any person with the appropriate receiving equipment to receive the signal and view or listen to the content without requiring a subscript ...

broadcasting (both television and radio). Satellite,

cable television

Cable television is a system of delivering television programming to consumers via radio frequency (RF) signals transmitted through coaxial cables, or in more recent systems, light pulses through fibre-optic cables. This contrasts with bro ...

, and Internet outlets are not subject to content-based FCC regulation. It can issue fines if, for example, the broadcaster employs certain

profane words. The Supreme Court in 1978 in ''

FCC v. Pacifica Foundation'' upheld the commission's determination that

George Carlin's classic "

seven dirty words

The seven dirty words are seven English-language curse words that American comedian George Carlin first listed in his 1972 "Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television" monologue. The words, in the order Carlin listed them, are: "shit", " piss", ...

" monologue, with its deliberate, repetitive and creative use of vulgarities, was indecent. But the court at that time left open the question of whether the use of "an occasional expletive" could be punished. Radio personality

Howard Stern

Howard Allan Stern (born January 12, 1954) is an American radio and television personality, comedian, and author. He is best known for his radio show, ''The Howard Stern Show'', which gained popularity when it was nationally syndicated on terre ...

has been a frequent target of fines. This led to his leaving broadcast radio and signing on with

Sirius Satellite Radio

Sirius Satellite Radio was a satellite radio ( SDARS) and online radio service operating in North America, owned by Sirius XM Holdings.

Headquartered in New York City, with smaller studios in Los Angeles and Memphis, Sirius was officially la ...

in 2006. The

Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show controversy

The Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show, which was broadcast live on February 1, 2004, from Houston, Texas, on the CBS television network, is notable for a moment in which Janet Jackson's breast—adorned with a nipple shield—was expos ...

increased the political pressure on the FCC to vigorously police the airwaves. In addition,

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

increased the maximum fine the FCC may levy from US$268,500 to US$375,000 per incident.

The Supreme Court, in its 5–4 decision in ''

FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc.'' (2009), said it did not find the FCC's policy on so-called fleeting expletives either "arbitrary or capricious", thus dealing a blow to the networks in their efforts to scuttle the policy. But the case brought by Fox to the high court was a narrow challenge on procedural grounds to the manner in which the FCC handled its decision to toughen up its policy on fleeting expletives. Fox, with the support of ABC, CBS, and NBC, argued that the commission did not give enough notice of nor properly explain the reasons for clamping down on fleeting expletives after declining to issue penalties for them in decades past. The issue first arose in 2004, when the FCC sanctioned but did not fine, NBC for

Bono

Paul David Hewson (born 10 May 1960), known by his stage name Bono (), is an Irish singer-songwriter, activist, and philanthropist. He is the lead vocalist and primary lyricist of the rock band U2.

Born and raised in Dublin, he attended ...

's use of the phrase "fucking brilliant" during the Golden Globes telecast. The present case arose from two appearances by celebrities on the Billboard Music Awards. The first involved

Cher

Cher (; born Cherilyn Sarkisian; May 20, 1946) is an American singer, actress and television personality. Often referred to by the media as the "Goddess of Pop", she has been described as embodying female autonomy in a male-dominated industr ...

, who reflected on her career in accepting an award in 2002: "I've also had critics for the last forty years saying I was on my way out every year. Right. So fuck 'em." The second passage came in an exchange between

Paris Hilton

Paris Whitney Hilton (born February 17, 1981) is an American media personality, businesswoman, socialite, model, and entertainer. Born in New York City, and raised there and in Beverly Hills, California, she is a great-granddaughter of Conr ...

and

Nicole Richie

Nicole Camille Richie (; born September 21, 1981) is an American television personality, fashion designer, socialite, and actress. She came to prominence after appearing in the reality television series ''The Simple Life'' (2003–2007), in whic ...

in 2003 in which Richie asked, "Have you ever tried cleaning cow shit off a Prada purse? It's not so fucking simple."

The majority decision, written by Justice

Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

, reversed the lower appellate court's decision that the FCC's move was "arbitrary and capricious." "The commission could reasonably conclude," he wrote, "that the pervasiveness of foul language, and the coarsening of public entertainment in other media such as cable, justify more stringent regulation of broadcast programs so as to give conscientious parents a relatively safe haven for their children." Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, dissenting, wrote that "there is no way to hide the long shadow the First Amendment casts over what the commission has done. Today's decision does nothing to diminish that shadow." Justice John Paul Stevens, dissenting, wrote that not every use of a swear word connoted the same thing: "As any golfer who has watched his partner shank a short approach knows," Justice Stevens wrote, "it would be absurd to accept the suggestion that the resultant four-letter word uttered on the golf course describes sex or excrement and is therefore indecent... It is ironic, to say the least, that while the FCC patrols the airwaves for words that have a tenuous relationship with sex or excrement, commercials broadcast during prime-time hours frequently ask viewers whether they are battling erectile dysfunction or are having trouble going to the bathroom... The FCC's shifting and impermissibly vague indecency policy only imperils these broadcasters and muddles the regulatory landscape." For 30 years, the FCC has had the power to keep "indecent" material off the airwaves from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., and those rules "have not proved unworkable" Stevens added. Justice Breyer, dissenting, wrote that the law "grants those in charge of independent administrative agencies broad authority to determine relevant policy," he observed. "But it does not permit them to make policy choices for purely political reasons nor to rest them primarily upon unexplained policy preferences." Scalia's majority opinion was joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Justices Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr. and (for the most part) by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy. Justices Stevens, Ginsburg, Souter, and Breyer dissented. Four justices wrote concurrences or dissents speaking only for themselves.

But the decision was limited to a narrow procedural issue and also sent the case back to the 2nd Court of Appeals in New York to directly address the constitutionality of the FCC's policy. The 2nd Court of Appeals is already on record in its 2007 ruling that it was "skeptical" that the policy could "pass constitutional muster." Scalia said that the looming First Amendment question "will be determined soon enough, perhaps in this very case." The decision provided hints that the court might approach the constitutional question differently. Some dissenting justices and Justice Clarence Thomas, who was in the majority, indicated that they might be receptive to a First Amendment challenge. Thomas, in a concurrence, said he was "open to reconsideration" of the two cases that gave television broadcasters far less First Amendment protection than books, newspapers, cable programs and Web sites have.

The FCC is also responsible for permitting transmitters, to prevent interference between stations from obscuring each other's signals. Denial of the right to transmit could be considered censorship. Restrictions on

low-power broadcasting

Low-power broadcasting is broadcasting by a broadcast station at a low transmitter power output to a smaller service area than "full power" stations within the same region. It is often distinguished from "micropower broadcasting" (more commonly ...

stations have been particularly controversial, and the subject of legislation in the 1990s and 2000s (decade).

''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' reported U.S.

censorship of U.S. media regarding Raymond Allen Davis, a

CIA employee implicated in murder in that "A number of US media outlets learned about Davis's CIA role but have kept it under wraps at the request of the Obama administration."

Colorado station

KUSA censored an online report indicating Davis worked for the CIA when the station "removed the CIA reference from its website at the request of the US government."

On July 26, 2018, two

WKXW

WKXW (101.5 FM, "New Jersey 101.5") is a commercial FM radio station licensed to serve Trenton, New Jersey. It is owned by Townsquare Media. Its studios and offices are located in Ewing and its broadcast tower, which is shared with WPRB, is ...

radio show hosts were suspended for calling New Jersey attorney general

Gurbir Grewal

Gurbir Singh Grewal (; born June 23, 1973) is an American attorney and prosecutor who served as the sixty-first attorney general of the State of New Jersey from January 2018 until his resignation in July 2021. Appointed by Governor of New Jersey P ...

"turban man" on air.

Journalism in warzones

Reporters are often obliged to "embed" themselves with a squad or unit of soldiers before being granted official access to fields of battle. Reporters are limited in what they may report by means of contracts, punishment or forced relocation, and the inherent nature of being tied to and reliant upon a military unit for protection and presence.

Wartime censorship often involves forms of

mass surveillance

Mass surveillance is the intricate surveillance of an entire or a substantial fraction of a population in order to monitor that group of citizens. The surveillance is often carried out by local and federal governments or governmental organizatio ...

. For international communications, like those done by

Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

and

ITT, this mass surveillance continued after the wars were over. The

Black Chamber

The Black Chamber (1919–1929), also known as the Cipher Bureau, was the United States' first peacetime cryptanalytic organization, and a forerunner of the National Security Agency. The only prior codes and cypher organizations maintained by the ...

received the information after World War I. After World War II

NSA's Project SHAMROCK performed a similar function.

Comics

Film

The first act of movie censorship in the United States was an 1897 statute of the State of Maine that prohibited the exhibition of prizefight films. Maine enacted the statute to prevent the exhibition of the 1897 heavyweight championship between James J. Corbett and Robert Fitzsimmons. Some other states followed Maine.

In 1915, the US Supreme Court decided the case ''

Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio'' in which the court determined that

motion pictures

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

were purely commerce and not an art, and thus not covered by the

First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

. This decision was not overturned until the Supreme Court case, ''

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson

''Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson'', 343 U.S. 495 (1952), also referred to as the ''Miracle Decision'', was a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court that largely marked the decline of motion picture censorship in the United States. ...

'' in 1952. Popularly referred to as the "Miracle Decision", the ruling involved the short film "The Miracle", part of

Roberto Rossellini

Roberto Gastone Zeffiro Rossellini (8 May 1906 – 3 June 1977) was an Italian film director, producer, and screenwriter. He was one of the most prominent directors of the Italian neorealist cinema, contributing to the movement with films such ...

's

anthology film

An anthology film (also known as an omnibus film, package film, or portmanteau film) is a single film consisting of several shorter films, each complete in itself and distinguished from the other, though frequently tied together by a single theme ...

''

L'Amore'' (1948).

Between the ''Mutual Film'' and the ''Joseph Burstyn'' decisions local, state, and city censorship boards had the power to edit or ban films. City and state censorship ordinances are nearly as old as the movies themselves, and such ordinances banning the public exhibition of "immoral" films proliferated.

Public outcry over perceived immorality in Hollywood and the movies, as well as the growing number of city and state censorship boards, led the movie studios to fear that federal regulations were not far off; so they created, in 1922, the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors Association (which became the Motion Picture Association of America in 1945), an industry trade and lobby organization. The association was headed by

Will H. Hays, a well-connected Republican lawyer who had previously been United States Postmaster General; and he derailed attempts to institute federal censorship over the movies.

In 1927, Hays compiled a list of subjects, culled from his experience with the various US censorship boards, which he felt Hollywood studios would be wise to avoid. He called this list "the formula" but it was popularly known as the "don'ts and be carefuls" list. In 1930, Hays created the Studio Relations Committee (SRC) to implement his censorship code, but the SRC lacked any real enforcement capability.

The advent of

talking pictures in 1927 led to a perceived need for further enforcement.

Martin Quigley, the publisher of a Chicago-based motion picture trade newspaper, began lobbying for a more extensive code that not only listed material that was inappropriate for the movies, but also contained a moral system that the movies could help to promote—specifically, a system based on Catholic theology. He recruited Father

Daniel Lord, a Jesuit priest and instructor at the Catholic St. Louis University, to write such a code and on March 31, 1930 the board of directors of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association adopted it formally. This original version especially was once popularly known as the Hays Code, but it and its later revisions are now commonly called the

Production Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States from 1934 to 1968. It is also popularly known as the ...

.

However, Depression economics and changing social mores resulted in the studios producing racier fare that the Code, lacking an aggressive enforcement body, was unable to redress. This era is known as

Pre-Code Hollywood

Pre-Code Hollywood was the brief era in the Cinema of the United States, American film industry between the widespread adoption of sound in film in 1929LaSalle (2002), p. 1. and the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code censorshi ...

.

An amendment to the Code, adopted on June 13, 1934, established the Production Code Administration (PCA), and required all films released on or after July 1, 1934 to obtain a certificate of approval before being released. For more than thirty years following, virtually all motion pictures produced in the United States and released by major studios adhered to the code. The Production Code was not created or enforced by federal, state, or city government. In fact, the Hollywood studios adopted the code in large part in the hopes of avoiding government censorship, preferring self-regulation to government regulation.

The enforcement of the Production Code led to the dissolution of many local censorship boards. Meanwhile, the

US Customs Department prohibited the importation of the

Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech ...

film ''

Ecstasy'' (

1933

Events

January

* January 11 – Sir Charles Kingsford Smith makes the first commercial flight between Australia and New Zealand.

* January 17 – The United States Congress votes in favour of Philippines independence, against the wis ...

), starring an actress soon to be known as

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr (; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American film actress and inventor. A film star during Hollywood's golden age, Lamarr has been described as one of the greatest movie actresse ...

, an action which was upheld on appeal.

In 1934, Joseph I. Breen (1888–1965) was appointed head of the new Production Code Administration (PCA). Under Breen's leadership of the PCA, which lasted until his retirement in 1954, enforcement of the Production Code became rigid and notorious. Breen's power to change scripts and scenes angered many writers, directors, and Hollywood

moguls. The PCA had two offices, one in Hollywood, and the other in New York City. Films approved by the New York PCA office were issued certificate numbers that began with a zero.

The first major instance of censorship under the Production Code involved the 1934 film ''

Tarzan and His Mate

''Tarzan and His Mate'' is a 1934 American pre-Code action adventure film based on the Tarzan character created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Directed by Cedric Gibbons, it ...

'', in which brief nude scenes involving a body double for actress

Maureen O'Sullivan

Maureen O'Sullivan (17 May 1911 – 23 June 1998) was an Irish-American actress, who played Jane in the ''Tarzan'' series of films during the era of Johnny Weissmuller. She performed with such actors as Laurence Olivier, Greta Garbo, William ...

were edited out of the master negative of the film. Another famous case of enforcement involved the

1943

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 1 – WWII: The Soviet Union announces that 22 German divisions have been encircled at Stalingrad, with 175,000 killed and 137,650 captured.

* January 4 � ...

western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

''

The Outlaw

''The Outlaw'' is a 1943 American Western film, directed by Howard Hughes and starring Jack Buetel, Jane Russell, Thomas Mitchell, and Walter Huston. Hughes also produced the film, while Howard Hawks served as an uncredited co-director. The ...

'', produced by

Howard Hughes

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. (December 24, 1905 – April 5, 1976) was an American business magnate, record-setting pilot, engineer, film producer, and philanthropist, known during his lifetime as one of the most influential and richest people in th ...

. ''The Outlaw'' was denied a certificate of approval and kept out of theaters for years because the film's advertising focused particular attention on

Jane Russell

Ernestine Jane Geraldine Russell (June 21, 1921 – February 28, 2011) was an American actress, singer, and model. She was one of Hollywood's leading sex symbols in the 1940s and 1950s. She starred in more than 20 films.

Russell moved from th ...

's breasts. Hughes eventually persuaded Breen that the breasts did not violate the code and the film could be shown.

Some films produced outside the mainstream studio system during this time did flout the conventions of the code, such as ''

Child Bride

''Child Bride'', also known as ''Child Brides'', ''Child Bride of the Ozarks'' and ''Dust to Dust'' (USA reissue titles), is a 1938 '' (1938), which featured a nude scene involving 12-year-old actress

Shirley Mills. Even cartoon sex symbol

Betty Boop

Betty Boop is an animated cartoon character created by Max Fleischer, with help from animators including Grim Natwick.Pointer (2017) She originally appeared in the '' Talkartoon'' and ''Betty Boop'' film series, which were produced by Fleisch ...

had to change from being a

flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered accepta ...

, and began to wear an old-fashioned housewife skirt.

In 1952, in the case of ''

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson

''Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson'', 343 U.S. 495 (1952), also referred to as the ''Miracle Decision'', was a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court that largely marked the decline of motion picture censorship in the United States. ...

'', the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously overruled its 1915 decision and held that motion pictures were entitled to First Amendment protection, so that the

New York State Board of Regents The Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York is responsible for the general supervision of all educational activities within New York State, presiding over University of the State of New York and the New York State Education Depar ...

could not ban "The Miracle", a

short film

A short film is any motion picture that is short enough in running time not to be considered a feature film. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences defines a short film as "an original motion picture that has a running time of 40 minutes ...

that was one half of ''

L'Amore'' (1948), an

anthology film

An anthology film (also known as an omnibus film, package film, or portmanteau film) is a single film consisting of several shorter films, each complete in itself and distinguished from the other, though frequently tied together by a single theme ...

directed by

Roberto Rossellini

Roberto Gastone Zeffiro Rossellini (8 May 1906 – 3 June 1977) was an Italian film director, producer, and screenwriter. He was one of the most prominent directors of the Italian neorealist cinema, contributing to the movement with films such ...

. Film distributor

Joseph Burstyn

Joseph Burstyn (born Jossel Lejba Bursztyn; December 15, 1899 – November 29, 1953) was a Polish-American film distributor who specialized in the commercial release of foreign-language and American independent film productions.

Life and career

B ...

released the film in the U.S. in 1950, and the case became known as the "Miracle Decision" due to its connection to Rossellini's film. That in turn reduced the threat of government regulation that justified the Production Code, and the PCA's powers over the Hollywood industry were greatly reduced.

[Sperling, Millner, and Warner (1998), ''Hollywood Be Thy Name'', Prima Publishing, ISN:559858346 p. 325.]

At the forefront of challenges to the code was director

Otto Preminger

Otto Ludwig Preminger ( , ; 5 December 1905 – 23 April 1986) was an Austrian-American theatre and film director, film producer, and actor.

He directed more than 35 feature films in a five-decade career after leaving the theatre. He first gai ...

, whose films violated the code repeatedly in the 1950s. His

1953

Events

January

* January 6 – The Asian Socialist Conference opens in Rangoon, Burma.

* January 12 – Estonian émigrés found a government-in-exile in Oslo.

* January 14

** Marshal Josip Broz Tito is chosen President of Yugosl ...

film ''

The Moon is Blue

''The Moon Is Blue'' is a play by F. Hugh Herbert. A comedy in three acts, the play consists of one female and three male characters.

Performance history

''The Moon Is Blue'' premiered at The Playhouse in Wilmington, Delaware on February 16, 1 ...

'', about a young woman who tries to play two suitors off against each other by claiming that she plans to keep her virginity until marriage, was the first film to use the words "virgin", "seduce", and "mistress", and it was released without a certificate of approval. He later made ''

The Man with the Golden Arm

''The Man with the Golden Arm'' is a 1955 American drama film with elements of film noir directed by Otto Preminger, based on the novel of the same name by Nelson Algren. Starring Frank Sinatra, Eleanor Parker, Kim Novak, Arnold Stang and D ...

'' (

1955

Events January

* January 3 – José Ramón Guizado becomes president of Panama.

* January 17 – , the first nuclear-powered submarine, puts to sea for the first time, from Groton, Connecticut.

* January 18– 20 – Battle of Yijia ...

), which portrayed the prohibited subject of drug abuse, and ''

Anatomy of a Murder'' (

1959

Events January

* January 1 - Cuba: Fulgencio Batista flees Havana when the forces of Fidel Castro advance.

* January 2 - Lunar probe Luna 1 was the first man-made object to attain escape velocity from Earth. It reached the vicinity of ...

) which dealt with

rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or a ...

. Preminger's films were direct assaults on the authority of the Production Code and, since they were successful, hastened its abandonment.

In

1954

Events

January

* January 1 – The Soviet Union ceases to demand war reparations from West Germany.

* January 3 – The Italian broadcaster RAI officially begins transmitting.

* January 7 – Georgetown-IBM experiment: The fir ...

, Joseph Breen retired and

Geoffrey Shurlock was appointed as his successor. ''

Variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film) ...

'' noted "a decided tendency towards a broader, more casual approach" in the enforcement of the code.

Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder (; ; born Samuel Wilder; June 22, 1906 – March 27, 2002) was an Austrian-American filmmaker. His career in Hollywood spanned five decades, and he is regarded as one of the most brilliant and versatile filmmakers of Classic Hol ...

's ''

Some Like It Hot

''Some Like It Hot'' is a 1959 American crime comedy film directed, produced and co-written by Billy Wilder. It stars Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, with George Raft, Pat O'Brien, Joe E. Brown, Joan Shawlee, Grace Lee Whitney ...

'' (

1959

Events January

* January 1 - Cuba: Fulgencio Batista flees Havana when the forces of Fidel Castro advance.

* January 2 - Lunar probe Luna 1 was the first man-made object to attain escape velocity from Earth. It reached the vicinity of ...

) and

Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

's ''

Psycho'' (

1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events

January

* Jan ...

) were also released without a certificate of approval due to their themes and became box office hits, and as a result further weakened the authority of the code.

''The Pawnbroker'' and the end of the Code

In the early 1960s, British films such as ''

Victim

Victim(s) or The Victim may refer to:

People

* Crime victim

* Victim, in psychotherapy, a posited role in the Karpman drama triangle model of transactional analysis

Films and television

* ''The Victim'' (1916 film), an American silent film by ...

'' (1961), ''

A Taste of Honey

''A Taste of Honey'' is the first play by the British dramatist Shelagh Delaney, written when she was 19. It was intended as a novel, but she turned it into a play because she hoped to revitalise British theatre and address social issues that ...

'' (1961), and ''

The Leather Boys'' (1963) offered social commentary about gender roles and

homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, ma ...

that violated the Hollywood Production Code, yet the films were still released in America. The American

gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , ...

,

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

, and youth movements prompted a reevaluation of the depiction of themes of race, class, gender, and sexuality that had been restricted by the Code.

In 1964, ''

The Pawnbroker

''The Pawnbroker'' (1961) is a novel by Edward Lewis Wallant which tells the story of Sol Nazerman, a concentration camp survivor who suffers flashbacks of his past Nazi imprisonment as he tries to cope with his daily life operating a pawn sho ...

'', directed by

Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. He was nominated five times for the Academy Award: four for Best Director for '' 12 Angry Men'' (1957), '' Dog Day Afternoon'' (1975), '' Network'' (19 ...

and starring

Rod Steiger

Rodney Stephen Steiger (; April 14, 1925July 9, 2002, aged 77) was an American actor, noted for his portrayal of offbeat, often volatile and crazed characters. Cited as "one of Hollywood's most charismatic and dynamic stars," he is closely assoc ...

, was initially rejected because of two scenes in which the actresses

Linda Geiser and Thelma Oliver fully expose their breasts; and a sex scene between Oliver and