Cavity Magnetron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The cavity magnetron is a high-power

The original magnetron was very difficult to keep operating at the critical value, and even then the number of electrons in the circling state at any time was fairly low. This meant that it produced very low-power signals. Nevertheless, as one of the few devices known to create microwaves, interest in the device and potential improvements was widespread.

The first major improvement was the split-anode magnetron, also known as a negative-resistance magnetron. As the name implies, this design used an anode that was split in two—one at each end of the tube—creating two half-cylinders. When both were charged to the same voltage the system worked like the original model. But by slightly altering the voltage of the two plates, the electrons' trajectory could be modified so that they would naturally travel towards the lower voltage side. The plates were connected to an oscillator that reversed the relative voltage of the two plates at a given frequency.

At any given instant, the electron will naturally be pushed towards the lower-voltage side of the tube. The electron will then oscillate back and forth as the voltage changes. At the same time, a strong magnetic field is applied, stronger than the critical value in the original design. This would normally cause the electron to circle back to the cathode, but due to the oscillating electrical field, the electron instead follows a looping path that continues toward the anodes.

Since all of the electrons in the flow experienced this looping motion, the amount of RF energy being radiated was greatly improved. And as the motion occurred at any field level beyond the critical value, it was no longer necessary to carefully tune the fields and voltages, and the overall stability of the device was greatly improved. Unfortunately, the higher field also meant that electrons often circled back to the cathode, depositing their energy on it and causing it to heat up. As this normally causes more electrons to be released, it could sometimes lead to a runaway effect, damaging the device.

The original magnetron was very difficult to keep operating at the critical value, and even then the number of electrons in the circling state at any time was fairly low. This meant that it produced very low-power signals. Nevertheless, as one of the few devices known to create microwaves, interest in the device and potential improvements was widespread.

The first major improvement was the split-anode magnetron, also known as a negative-resistance magnetron. As the name implies, this design used an anode that was split in two—one at each end of the tube—creating two half-cylinders. When both were charged to the same voltage the system worked like the original model. But by slightly altering the voltage of the two plates, the electrons' trajectory could be modified so that they would naturally travel towards the lower voltage side. The plates were connected to an oscillator that reversed the relative voltage of the two plates at a given frequency.

At any given instant, the electron will naturally be pushed towards the lower-voltage side of the tube. The electron will then oscillate back and forth as the voltage changes. At the same time, a strong magnetic field is applied, stronger than the critical value in the original design. This would normally cause the electron to circle back to the cathode, but due to the oscillating electrical field, the electron instead follows a looping path that continues toward the anodes.

Since all of the electrons in the flow experienced this looping motion, the amount of RF energy being radiated was greatly improved. And as the motion occurred at any field level beyond the critical value, it was no longer necessary to carefully tune the fields and voltages, and the overall stability of the device was greatly improved. Unfortunately, the higher field also meant that electrons often circled back to the cathode, depositing their energy on it and causing it to heat up. As this normally causes more electrons to be released, it could sometimes lead to a runaway effect, damaging the device.

All cavity magnetrons consist of a heated cylindrical

All cavity magnetrons consist of a heated cylindrical

In a

In a

"Magnetron,"

U.S. patent no. 2,123,728 (filed: 1936 November 27 ; issued: 1938 July 12). However, the German military considered the frequency drift of Hollman's device to be undesirable, and based their radar systems on the klystron instead. But klystrons could not at that time achieve the high power output that magnetrons eventually reached. This was one reason that German night fighter radars, which never strayed beyond the low-UHF band to start with for front-line aircraft, were not a match for their British counterparts. Likewise, in the UK, Albert Beaumont Wood proposed in 1937 a system with "six or eight small holes" drilled in a metal block, differing from the later production designs only in the aspects of vacuum sealing. However, his idea was rejected by the Navy, who said their valve department was far too busy to consider it.

In 1940, at the University of Birmingham in the UK, John Randall and

In 1940, at the University of Birmingham in the UK, John Randall and

At least one hazard in particular is well known and documented. As the lens of the eye has no cooling blood flow, it is particularly prone to overheating when exposed to microwave radiation. This heating can in turn lead to a higher incidence of cataracts in later life.

There is also a considerable electrical hazard around magnetrons, as they require a high voltage power supply.

All magnetrons contain a small amount of thorium mixed with tungsten in their filament. While this is a radioactive metal, the risk of cancer is low as it never gets airborne in normal usage. Only if the filament is taken out of the magnetron, finely crushed, and inhaled can it pose a health hazard.

At least one hazard in particular is well known and documented. As the lens of the eye has no cooling blood flow, it is particularly prone to overheating when exposed to microwave radiation. This heating can in turn lead to a higher incidence of cataracts in later life.

There is also a considerable electrical hazard around magnetrons, as they require a high voltage power supply.

All magnetrons contain a small amount of thorium mixed with tungsten in their filament. While this is a radioactive metal, the risk of cancer is low as it never gets airborne in normal usage. Only if the filament is taken out of the magnetron, finely crushed, and inhaled can it pose a health hazard.

MagnetronsMagnetron collection in the Virtual Valve Museum

Videos of plasmoids created in a microwave oven

TMD Magnetrons

Information and PDF Data Sheets

Concise, notably-excellent article about magnetrons; Fig. 13 is representative of a modern radar magnetron. ;Patents * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cavity Magnetron Science and technology during World War II English inventions Microwave technology Radar Vacuum tubes World War II British electronics World War II American electronics

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

used in early radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

s using the interaction of a stream of electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have n ...

s with a magnetic field while moving past a series of cavity resonators, which are small, open cavities in a metal block. Electrons pass by the cavities and cause microwaves to oscillate within, similar to the functioning of a whistle producing a tone when excited by an air stream blown past its opening. The resonant frequency of the arrangement is determined by the cavities' physical dimensions. Unlike other vacuum tubes, such as a klystron or a traveling-wave tube (TWT), the magnetron cannot function as an amplifier for increasing the intensity of an applied microwave signal; the magnetron serves solely as an oscillator, generating a microwave signal from direct current electricity supplied to the vacuum tube.

The use of magnetic fields as a means to control the flow of an electrical current was spurred by the invention of the Audion by Lee de Forest in 1906. Albert Hull

Albert Wallace Hull (19 April 1880 – 22 January 1966) was an American physicist and electrical engineer who made contributions to the development of vacuum tubes, and invented the magnetron. He was a member of the National Academy of Sci ...

of General Electric Research Laboratory, USA, began development of magnetrons to avoid de Forest's patents,Redhead, Paul A., "The Invention of the Cavity Magnetron and its Introduction into Canada and the U.S.A.", ''La Physique au Canada'', November 2001 but these were never completely successful. Other experimenters picked up on Hull's work and a key advance, the use of two cathodes, was introduced by Habann in Germany in 1924. Further research was limited until Okabe's 1929 Japanese paper noting the production of centimeter-wavelength signals, which led to worldwide interest. The development of magnetrons with multiple cathodes was proposed by A. L. Samuel of Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1934, leading to designs by Postumus in 1934 and Hans Hollmann

Hans Erich (Eric) Hollmann (4 November 1899 – 19 November 1960) was a German electronic specialist who made several breakthroughs in the development of radar.

Hollmann was born in Solingen, Germany. He became interested in radio and even a ...

in 1935. Production was taken up by Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters is ...

, General Electric Company (GEC), Telefunken and others, limited to perhaps 10 W output. By this time the klystron was producing more power and the magnetron was not widely used, although a 300W device was built by Aleksereff and Malearoff in the USSR in 1936 (published in 1940).

The ''cavity'' magnetron was a radical improvement introduced by John Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

at the University of Birmingham, England in 1940. Their first working example produced hundreds of watts at 10 cm wavelength, an unprecedented achievement. Within weeks, engineers at GEC had improved this to well over a kilowatt, and within months 25 kilowatts, over 100 kW by 1941 and pushing towards a megawatt by 1943. The high power pulses were generated from a device the size of a small book and transmitted from an antenna only centimeters long, reducing the size of practical radar systems by orders of magnitude. New radars appeared for night-fighter

A night fighter (also known as all-weather fighter or all-weather interceptor for a period of time after the Second World War) is a fighter aircraft adapted for use at night or in other times of bad visibility. Night fighters began to be used ...

s, anti-submarine aircraft and even the smallest escort ships, and from that point on the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

held a lead in radar that their counterparts in Germany and Japan were never able to close. By the end of the war, practically every Allied radar was based on a magnetron.

The magnetron continued to be used in radar in the post-war period but fell from favour in the 1960s as high-power klystrons and traveling-wave tubes emerged. A key characteristic of the magnetron is that its output signal changes from pulse to pulse, both in frequency and phase. This renders it less suitable for pulse-to-pulse comparisons for performing moving target indication and removing " clutter" from the radar display. The magnetron remains in use in some radar systems, but has become much more common as a low-cost source for microwave ovens. In this form, over one billion magnetrons are in use today.

Construction and operation

Conventional tube design

In a conventional electron tube (vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

), electrons

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have n ...

are emitted from a negatively charged, heated component called the cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. A conventional current describes the direction in whi ...

and are attracted to a positively charged component called the anode

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ...

. The components are normally arranged concentrically, placed within a tubular-shaped container from which all air has been evacuated, so that the electrons can move freely (hence the name "vacuum" tubes, called "valves" in British English).

If a third electrode (called a control grid) is inserted between the cathode and the anode, the flow of electrons between the cathode and anode can be regulated by varying the voltage on this third electrode. This allows the resulting electron tube (called a " triode" because it now has three electrodes) to function as an amplifier because small variations in the electric charge applied to the control grid will result in identical variations in the much larger current of electrons flowing between the cathode and anode.

Hull or single-anode magnetron

The idea of using a grid for control was invented by Philipp Lenard, who received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1905. In the USA it was later patented by Lee de Forest, resulting in considerable research into alternate tube designs that would avoid his patents. One concept used a magnetic field instead of an electrical charge to control current flow, leading to the development of the magnetron tube. In this design, the tube was made with two electrodes, typically with the cathode in the form of a metal rod in the center, and the anode as a cylinder around it. The tube was placed between the poles of a horseshoe magnet arranged such that the magnetic field was aligned parallel to the axis of the electrodes. With no magnetic field present, the tube operates as a diode, with electrons flowing directly from the cathode to the anode. In the presence of the magnetic field, the electrons will experience a force at right angles to their direction of motion, according to the left-hand rule. In this case, the electrons follow a curved path between the cathode and anode. The curvature of the path can be controlled by varying either the magnetic field using anelectromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

, or by changing the electrical potential between the electrodes.

At very high magnetic field settings the electrons are forced back onto the cathode, preventing current flow. At the opposite extreme, with no field, the electrons are free to flow straight from the cathode to the anode. There is a point between the two extremes, the critical value or Hull cut-off magnetic field (and cut-off voltage), where the electrons just reach the anode. At fields around this point, the device operates similar to a triode. However, magnetic control, due to hysteresis and other effects, results in a slower and less faithful response to control current than electrostatic control using a control grid in a conventional triode (not to mention greater weight and complexity), so magnetrons saw limited use in conventional electronic designs.

It was noticed that when the magnetron was operating at the critical value, it would emit energy in the radio frequency

Radio frequency (RF) is the oscillation rate of an alternating electric current or voltage or of a magnetic, electric or electromagnetic field or mechanical system in the frequency range from around to around . This is roughly between the up ...

spectrum. This occurs because a few of the electrons, instead of reaching the anode, continue to circle in the space between the cathode and the anode. Due to an effect now known as cyclotron radiation, these electrons radiate radio frequency energy. The effect is not very efficient. Eventually the electrons hit one of the electrodes, so the number in the circulating state at any given time is a small percentage of the overall current. It was also noticed that the frequency of the radiation depends on the size of the tube, and even early examples were built that produced signals in the microwave regime.

Early conventional tube systems were limited to the high frequency bands, and although very high frequency systems became widely available in the late 1930s, the ultra high frequency and microwave bands were well beyond the ability of conventional circuits. The magnetron was one of the few devices able to generate signals in the microwave band and it was the only one that was able to produce high power at centimeter wavelengths.

Split-anode magnetron

The original magnetron was very difficult to keep operating at the critical value, and even then the number of electrons in the circling state at any time was fairly low. This meant that it produced very low-power signals. Nevertheless, as one of the few devices known to create microwaves, interest in the device and potential improvements was widespread.

The first major improvement was the split-anode magnetron, also known as a negative-resistance magnetron. As the name implies, this design used an anode that was split in two—one at each end of the tube—creating two half-cylinders. When both were charged to the same voltage the system worked like the original model. But by slightly altering the voltage of the two plates, the electrons' trajectory could be modified so that they would naturally travel towards the lower voltage side. The plates were connected to an oscillator that reversed the relative voltage of the two plates at a given frequency.

At any given instant, the electron will naturally be pushed towards the lower-voltage side of the tube. The electron will then oscillate back and forth as the voltage changes. At the same time, a strong magnetic field is applied, stronger than the critical value in the original design. This would normally cause the electron to circle back to the cathode, but due to the oscillating electrical field, the electron instead follows a looping path that continues toward the anodes.

Since all of the electrons in the flow experienced this looping motion, the amount of RF energy being radiated was greatly improved. And as the motion occurred at any field level beyond the critical value, it was no longer necessary to carefully tune the fields and voltages, and the overall stability of the device was greatly improved. Unfortunately, the higher field also meant that electrons often circled back to the cathode, depositing their energy on it and causing it to heat up. As this normally causes more electrons to be released, it could sometimes lead to a runaway effect, damaging the device.

The original magnetron was very difficult to keep operating at the critical value, and even then the number of electrons in the circling state at any time was fairly low. This meant that it produced very low-power signals. Nevertheless, as one of the few devices known to create microwaves, interest in the device and potential improvements was widespread.

The first major improvement was the split-anode magnetron, also known as a negative-resistance magnetron. As the name implies, this design used an anode that was split in two—one at each end of the tube—creating two half-cylinders. When both were charged to the same voltage the system worked like the original model. But by slightly altering the voltage of the two plates, the electrons' trajectory could be modified so that they would naturally travel towards the lower voltage side. The plates were connected to an oscillator that reversed the relative voltage of the two plates at a given frequency.

At any given instant, the electron will naturally be pushed towards the lower-voltage side of the tube. The electron will then oscillate back and forth as the voltage changes. At the same time, a strong magnetic field is applied, stronger than the critical value in the original design. This would normally cause the electron to circle back to the cathode, but due to the oscillating electrical field, the electron instead follows a looping path that continues toward the anodes.

Since all of the electrons in the flow experienced this looping motion, the amount of RF energy being radiated was greatly improved. And as the motion occurred at any field level beyond the critical value, it was no longer necessary to carefully tune the fields and voltages, and the overall stability of the device was greatly improved. Unfortunately, the higher field also meant that electrons often circled back to the cathode, depositing their energy on it and causing it to heat up. As this normally causes more electrons to be released, it could sometimes lead to a runaway effect, damaging the device.

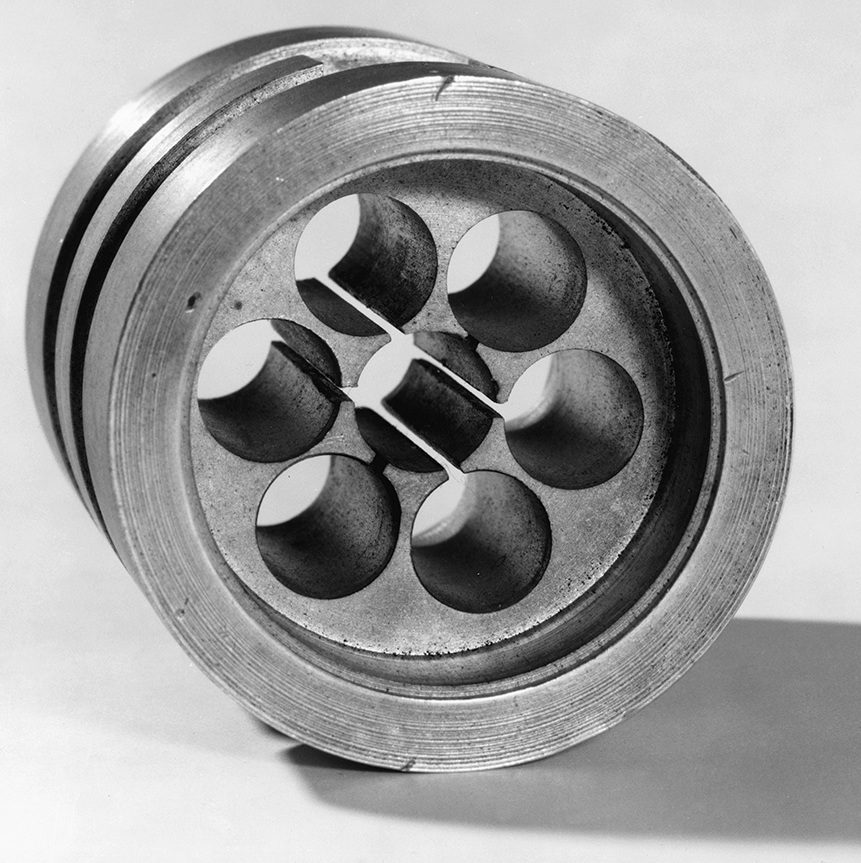

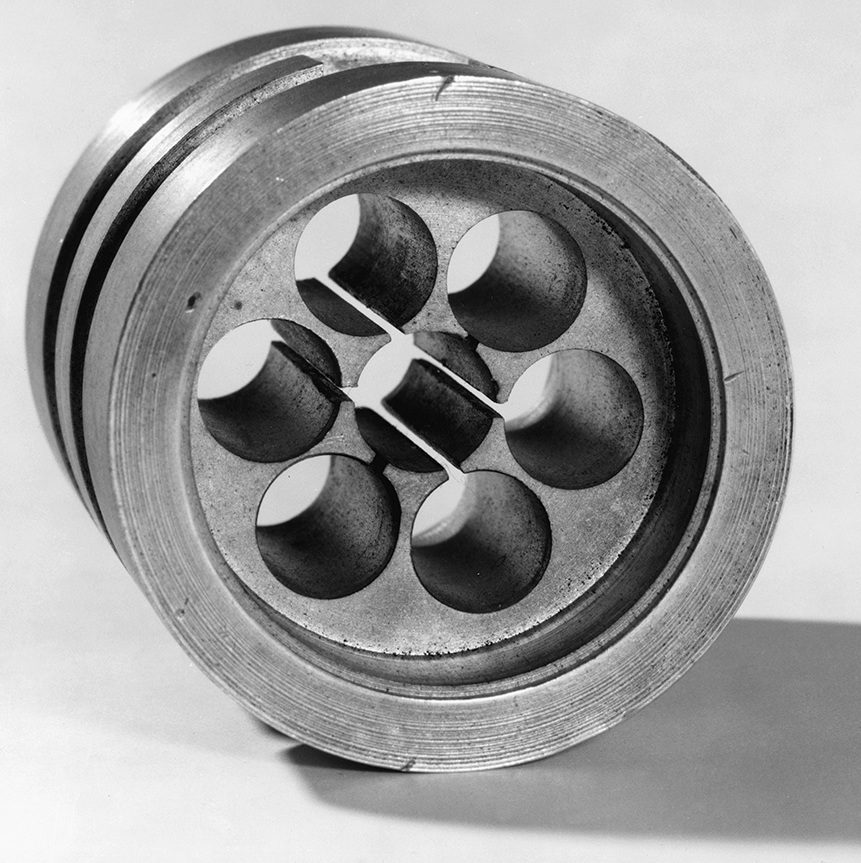

Cavity magnetron

The great advance in magnetron design was the resonant cavity magnetron or electron-resonance magnetron, which works on entirely different principles. In this design the oscillation is created by the physical shape of the anode, rather than external circuits or fields. Mechanically, the cavity magnetron consists of a large, solid cylinder of metal with a hole drilled through the centre of the circular face. A wire acting as the cathode is run down the center of this hole, and the metal block itself forms the anode. Around this hole, known as the "interaction space", are a number of similar holes ("resonators") drilled parallel to the interaction space, connected to the interaction space by a short channel. The resulting block looks something like the cylinder on a revolver, with a somewhat larger central hole. Early models were cut using Colt pistol jigs. Remembering that in an AC circuit the electrons travel along the surface, not the core, of the conductor, the parallel sides of the slot acts as acapacitor

A capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field by virtue of accumulating electric charges on two close surfaces insulated from each other. It is a passive electronic component with two terminals.

The effect of ...

while the round holes form an inductor

An inductor, also called a coil, choke, or reactor, is a passive two-terminal electrical component that stores energy in a magnetic field when electric current flows through it. An inductor typically consists of an insulated wire wound into a c ...

: an LC circuit made of solid copper, with the resonant frequency defined entirely by its dimensions.

The magnetic field is set to a value well below the critical, so the electrons follow arcing paths towards the anode. When they strike the anode, they cause it to become negatively charged in that region. As this process is random, some areas will become more or less charged than the areas around them. The anode is constructed of a highly conductive material, almost always copper, so these differences in voltage cause currents to appear to even them out. Since the current has to flow around the outside of the cavity, this process takes time. During that time additional electrons will avoid the hot spots and be deposited further along the anode, as the additional current flowing around it arrives too. This causes an oscillating current to form as the current tries to equalize one spot, then another.

The oscillating currents flowing around the cavities, and their effect on the electron flow within the tube, cause large amounts of microwave radiofrequency energy to be generated in the cavities. The cavities are open on one end, so the entire mechanism forms a single, larger, microwave oscillator. A "tap", normally a wire formed into a loop, extracts microwave energy from one of the cavities. In some systems the tap wire is replaced by an open hole, which allows the microwaves to flow into a waveguide.

As the oscillation takes some time to set up, and is inherently random at the start, subsequent startups will have different output parameters. Phase is almost never preserved, which makes the magnetron difficult to use in phased array systems. Frequency also drifts from pulse to pulse, a more difficult problem for a wider array of radar systems. Neither of these present a problem for continuous-wave radars, nor for microwave ovens.

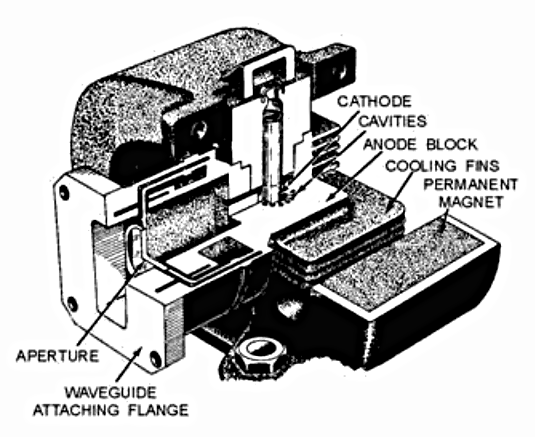

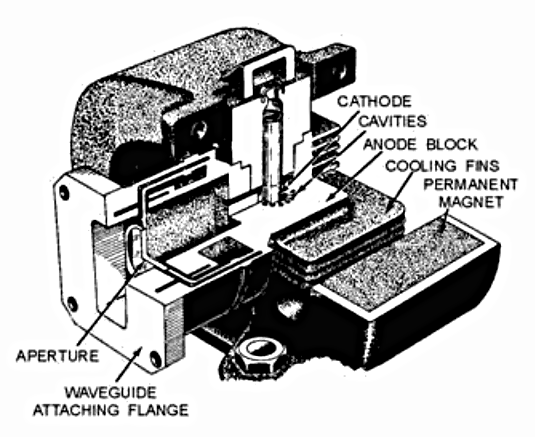

Common features

All cavity magnetrons consist of a heated cylindrical

All cavity magnetrons consist of a heated cylindrical cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. A conventional current describes the direction in whi ...

at a high (continuous or pulsed) negative potential created by a high-voltage, direct-current power supply. The cathode is placed in the center of an evacuated, lobed, circular metal chamber. The walls of the chamber are the anode of the tube. A magnetic field parallel to the axis of the cavity is imposed by a permanent magnet. The electrons initially move radially outward from the cathode attracted by the electric field of the anode walls. The magnetic field causes the electrons to spiral outward in a circular path, a consequence of the Lorentz force. Spaced around the rim of the chamber are cylindrical cavities. Slots are cut along the length of the cavities that open into the central, common cavity space. As electrons sweep past these slots, they induce a high-frequency radio field in each resonant cavity, which in turn causes the electrons to bunch into groups. A portion of the radio frequency energy is extracted by a short coupling loop that is connected to a waveguide (a metal tube, usually of rectangular cross section). The waveguide directs the extracted RF energy to the load, which may be a cooking chamber in a microwave oven or a high-gain antenna

Antenna ( antennas or antennae) may refer to:

Science and engineering

* Antenna (radio), also known as an aerial, a transducer designed to transmit or receive electromagnetic (e.g., TV or radio) waves

* Antennae Galaxies, the name of two collid ...

in the case of radar.

The sizes of the cavities determine the resonant frequency, and thereby the frequency of the emitted microwaves. However, the frequency is not precisely controllable. The operating frequency varies with changes in load impedance, with changes in the supply current, and with the temperature of the tube. This is not a problem in uses such as heating, or in some forms of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

where the receiver can be synchronized with an imprecise magnetron frequency. Where precise frequencies are needed, other devices, such as the klystron are used.

The magnetron is a self-oscillating device requiring no external elements other than a power supply. A well-defined threshold anode voltage must be applied before oscillation will build up; this voltage is a function of the dimensions of the resonant cavity, and the applied magnetic field. In pulsed applications there is a delay of several cycles before the oscillator achieves full peak power, and the build-up of anode voltage must be coordinated with the build-up of oscillator output.L.W. Turner,(ed),'' Electronics Engineer's Reference Book, 4th ed.'' Newnes-Butterworth, London 1976 , pp. 7-71 to 7-77

Where there are an even number of cavities, two concentric rings can connect alternate cavity walls to prevent inefficient modes of oscillation. This is called pi-strapping because the two straps lock the phase difference between adjacent cavities at π radians (180°).

The modern magnetron is a fairly efficient device. In a microwave oven, for instance, a 1.1-kilowatt input will generally create about 700 watts of microwave power, an efficiency of around 65%. (The high-voltage and the properties of the cathode determine the power of a magnetron.) Large S band magnetrons can produce up to 2.5 megawatts peak power with an average power of 3.75 kW. Some large magnetrons are water cooled. The magnetron remains in widespread use in roles which require high power, but where precise control over frequency and phase is unimportant.

Applications

Radar

In a

In a radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

set, the magnetron's waveguide is connected to an antenna

Antenna ( antennas or antennae) may refer to:

Science and engineering

* Antenna (radio), also known as an aerial, a transducer designed to transmit or receive electromagnetic (e.g., TV or radio) waves

* Antennae Galaxies, the name of two collid ...

. The magnetron is operated with very short pulses of applied voltage, resulting in a short pulse of high-power microwave energy being radiated. As in all primary radar systems, the radiation reflected from a target is analyzed to produce a radar map on a screen.

Several characteristics of the magnetron's output make radar use of the device somewhat problematic. The first of these factors is the magnetron's inherent instability in its transmitter frequency. This instability results not only in frequency shifts from one pulse to the next, but also a frequency shift within an individual transmitted pulse. The second factor is that the energy of the transmitted pulse is spread over a relatively wide frequency spectrum, which requires the receiver to have a correspondingly wide bandwidth. This wide bandwidth allows ambient electrical noise to be accepted into the receiver, thus obscuring somewhat the weak radar echoes, thereby reducing overall receiver signal-to-noise ratio and thus performance. The third factor, depending on application, is the radiation hazard caused by the use of high-power electromagnetic radiation. In some applications, for example, a marine radar

Marine radars are X band or S band radars on ships, used to detect other ships and land obstacles, to provide bearing and distance for collision avoidance and navigation at sea. They are electronic navigation instruments that use a rotatin ...

mounted on a recreational vessel, a radar with a magnetron output of 2 to 4 kilowatts is often found mounted very near an area occupied by crew or passengers. In practical use these factors have been overcome, or merely accepted, and there are today thousands of magnetron aviation and marine radar units in service. Recent advances in aviation weather-avoidance radar and in marine radar have successfully replaced the magnetron with microwave semiconductor oscillators, which have a narrower output frequency range. These allow a narrower receiver bandwidth to be used, and the higher signal-to-noise ratio in turn allows a lower transmitter power, reducing exposure to EMR.

Heating

In microwave ovens, the waveguide leads to a radio-frequency-transparent port into the cooking chamber. As the fixed dimensions of the chamber and its physical closeness to the magnetron would normally create standing wave patterns in the chamber, the pattern is randomized by a motorized fan-like ''mode stirrer

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

'' in the waveguide (more often in commercial ovens), or by a turntable that rotates the food (most common in consumer ovens).

An early example of this application was when British scientists in 1954 used a microwave oven to resurrect cryogenically

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures.

The 13th IIR International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington DC in 1971) endorsed a universal definition of “cryogenics” and “ ...

frozen hamsters.

Lighting

In microwave-excited lighting systems, such as a sulfur lamp, a magnetron provides the microwave field that is passed through a waveguide to the lighting cavity containing the light-emitting substance (e.g., sulfur, metal halides, etc.). Although efficient, these lamps are much more complex than other methods of lighting and therefore not commonly used. More modern variants useHEMT

A high-electron-mobility transistor (HEMT), also known as heterostructure FET (HFET) or modulation-doped FET (MODFET), is a field-effect transistor incorporating a junction between two materials with different band gaps (i.e. a heterojunction ...

s or GaN-on-SiC power semiconductor device

A power semiconductor device is a semiconductor device used as a switch or rectifier in power electronics (for example in a switch-mode power supply). Such a device is also called a power device or, when used in an integrated circuit, a power IC. ...

s to generate the microwaves, which are substantially less complex and can be adjusted to maximize light output using a PID controller.

History

In 1910 Hans Gerdien (1877–1951) of the Siemens Corporation invented a magnetron. In 1912, Swiss physicistHeinrich Greinacher

Heinrich Greinacher (May 31, 1880 in St. Gallen – April 17, 1974 in Bern) was a Swiss physicist. He is regarded as an original experimenter and is the developer of the magnetron and the Greinacher multiplier.

Greinacher was the only child of ...

was looking for new ways to calculate the electron mass

The electron mass (symbol: ''m''e) is the mass of a stationary electron, also known as the invariant mass of the electron. It is one of the fundamental constants of physics. It has a value of about or about , which has an energy-equivalent o ...

. He settled on a system consisting of a diode with a cylindrical anode surrounding a rod-shaped cathode, placed in the middle of a magnet. The attempt to measure the electron mass failed because he was unable to achieve a good vacuum in the tube. However, as part of this work, Greinacher developed mathematical models of the motion of the electrons in the crossed magnetic and electric fields.

In the US, Albert Hull

Albert Wallace Hull (19 April 1880 – 22 January 1966) was an American physicist and electrical engineer who made contributions to the development of vacuum tubes, and invented the magnetron. He was a member of the National Academy of Sci ...

put this work to use in an attempt to bypass Western Electric's patents on the triode. Western Electric had gained control of this design by buying Lee De Forest's patents on the control of current flow using electric fields via the "grid". Hull intended to use a variable magnetic field, instead of an electrostatic one, to control the flow of the electrons from the cathode to the anode. Working at General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable ene ...

's Research Laboratories in Schenectady, New York

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Yo ...

, Hull built tubes that provided switching through the control of the ratio of the magnetic and electric field strengths. He released several papers and patents on the concept in 1921.

Hull's magnetron was not originally intended to generate VHF (very-high-frequency) electromagnetic waves. However, in 1924, Czech physicist August Žáček (1886–1961) and German physicist Erich Habann (1892–1968) independently discovered that the magnetron could generate waves of 100 megahertz to 1 gigahertz. Žáček, a professor at Prague's Charles University, published first; however, he published in a journal with a small circulation and thus attracted little attention. Habann, a student at the University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The ...

, investigated the magnetron for his doctoral dissertation of 1924. Throughout the 1920s, Hull and other researchers around the world worked to develop the magnetron. Most of these early magnetrons were glass vacuum tubes with multiple anodes. However, the two-pole magnetron, also known as a split-anode magnetron, had relatively low efficiency.

While radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

was being developed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, there arose an urgent need for a high-power microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

generator that worked at shorter wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

s, around 10 cm (3 GHz), rather than the 50 to 150 cm (200 MHz) that was available from tube-based generators of the time. It was known that a multi-cavity resonant magnetron had been developed and patented in 1935 by Hans Hollmann

Hans Erich (Eric) Hollmann (4 November 1899 – 19 November 1960) was a German electronic specialist who made several breakthroughs in the development of radar.

Hollmann was born in Solingen, Germany. He became interested in radio and even a ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

.Hollmann, Hans Erich"Magnetron,"

U.S. patent no. 2,123,728 (filed: 1936 November 27 ; issued: 1938 July 12). However, the German military considered the frequency drift of Hollman's device to be undesirable, and based their radar systems on the klystron instead. But klystrons could not at that time achieve the high power output that magnetrons eventually reached. This was one reason that German night fighter radars, which never strayed beyond the low-UHF band to start with for front-line aircraft, were not a match for their British counterparts. Likewise, in the UK, Albert Beaumont Wood proposed in 1937 a system with "six or eight small holes" drilled in a metal block, differing from the later production designs only in the aspects of vacuum sealing. However, his idea was rejected by the Navy, who said their valve department was far too busy to consider it.

In 1940, at the University of Birmingham in the UK, John Randall and

In 1940, at the University of Birmingham in the UK, John Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

produced a working prototype of a cavity magnetron that produced about 400 W. Within a week this had improved to 1 kW, and within the next few months, with the addition of water cooling and many detail changes, this had improved to 10 and then 25 kW. To deal with its drifting frequency, they sampled the output signal and synchronized their receiver to whatever frequency was actually being generated. In 1941, the problem of frequency instability was solved by James Sayers

James Sayers (or Sayer) (1748 – April 20, 1823) was an English caricaturist . Many of his works are described in the Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum which h ...

coupling ("strapping") alternate cavities within the magnetron, which reduced the instability by a factor of 5–6. (For an overview of early magnetron designs, including that of Boot and Randall, see .) According to Andy Manning from the RAF Air Defence Radar Museum

The Royal Air Force Air Defence Radar Museum is a museum on the site of the former Royal Air Force radar and control base RAF Neatishead, close to the village of Horning in Norfolk, England.

The museum's exhibitions cover the history of air d ...

, Randall and Boot's discovery was "a massive, massive breakthrough" and "deemed by many, even now, to be the most important invention that came out of the Second World War", while professor of military history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, David Zimmerman, states:

Because France had just fallen to the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

s and Britain had no money to develop the magnetron on a massive scale, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

agreed that Sir Henry Tizard should offer the magnetron to the Americans in exchange for their financial and industrial help. An early 10 kW version, built in England by the General Electric Company Research Laboratories, Wembley, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

(not to be confused with the similarly named American company General Electric), was taken on the Tizard Mission in September 1940. As the discussion turned to radar, the US Navy representatives began to detail the problems with their short-wavelength systems, complaining that their klystrons could only produce 10 W. With a flourish, "Taffy" Bowen pulled out a magnetron and explained it produced 1000 times that.

Bell Telephone Laboratories took the example and quickly began making copies, and before the end of 1940, the Radiation Laboratory had been set up on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

to develop various types of radar using the magnetron. By early 1941, portable centimetric airborne radars were being tested in American and British aircraft. In late 1941, the Telecommunications Research Establishment in the United Kingdom used the magnetron to develop a revolutionary airborne, ground-mapping radar codenamed H2S. The H2S radar was in part developed by Alan Blumlein and Bernard Lovell

Sir Alfred Charles Bernard Lovell (31 August 19136 August 2012) was an English physicist and radio astronomer. He was the first director of Jodrell Bank Observatory, from 1945 to 1980.

Early life and education

Lovell was born at Oldland Com ...

.

The cavity magnetron was widely used during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in microwave radar equipment and is often credited with giving Allied radar a considerable performance advantage over German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

ese radars, thus directly influencing the outcome of the war. It was later described by American historian James Phinney Baxter III

James Phinney Baxter III (February 15, 1893 in Portland, Maine – June 17, 1975 in Williamstown, Massachusetts) was an American historian, educator, and academic, who won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for History for his book ''Scientists Against Time ...

as " e most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores".

Centimetric radar, made possible by the cavity magnetron, allowed for the detection of much smaller objects and the use of much smaller antennas. The combination of small-cavity magnetrons, small antennas, and high resolution allowed small, high quality radars to be installed in aircraft. They could be used by maritime patrol aircraft to detect objects as small as a submarine periscope, which allowed aircraft to attack and destroy submerged submarines which had previously been undetectable from the air. Centimetric contour mapping radars like H2S improved the accuracy of Allied bombers used in the strategic bombing campaign, despite the existence of the German FuG 350 ''Naxos'' device to specifically detect it. Centimetric gun-laying radars were likewise far more accurate than the older technology. They made the big-gunned Allied battleships more deadly and, along with the newly developed proximity fuze, made anti-aircraft guns much more dangerous to attacking aircraft. The two coupled together and used by anti-aircraft batteries, placed along the flight path of German V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb or doodlebug and in Germany ...

s on their way to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, are credited with destroying many of the flying bombs before they reached their target.

Since then, many millions of cavity magnetrons have been manufactured; while some have been for radar the vast majority have been for microwave ovens. The use in radar itself has dwindled to some extent, as more accurate signals have generally been needed and developers have moved to klystron and traveling-wave tube systems for these needs.

Health hazards

See also

*Crossed-field amplifier

A crossed-field amplifier (CFA) is a specialized vacuum tube, first introduced in the mid-1950s and frequently used as a microwave amplifier in very-high-power transmitters.

Raytheon engineer William C. Brown's work to adapt magnetron principle ...

* Yoji Ito

was an engineer and scientist who had a major role in the Japanese development of magnetrons and the Radio Range Finder (RRF – the code name for a radar).

Early years

Yoji Ito was born and raised in Onjuku, then a fishing village in the Chib ...

, a Japanese military electronics expert who helped create Japan's first cavity magnetron devices as early as 1939.

* Klystron

* Maser

A maser (, an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves through amplification by stimulated emission. The first maser was built by Charles H. Townes, James ...

* Microwave EMP Rifle

A directed-energy weapon (DEW) is a ranged weapon that damages its target with highly focused energy without a solid projectile, including lasers, microwaves, particle beams, and sound beams. Potential applications of this technology include ...

* Radiation Laboratory

* Traveling-wave tube

References

External links

;InformationMagnetrons

Videos of plasmoids created in a microwave oven

TMD Magnetrons

Information and PDF Data Sheets

Concise, notably-excellent article about magnetrons; Fig. 13 is representative of a modern radar magnetron. ;Patents * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cavity Magnetron Science and technology during World War II English inventions Microwave technology Radar Vacuum tubes World War II British electronics World War II American electronics