Cave diving on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cave-diving is

Cave-diving is

The procedures of cave-diving have much in common with procedures used for other types of

The procedures of cave-diving have much in common with procedures used for other types of

Most open-water diving skills apply to cave-diving, and there are additional skills specific to the environment, and to the chosen equipment configuration.

*Good buoyancy control, trim and finning technique help preserve visibility in areas with silt deposits. The ability to reverse kick to back out of restrictions where there is no space to turn around is useful.

**Finning skills:

Most open-water diving skills apply to cave-diving, and there are additional skills specific to the environment, and to the chosen equipment configuration.

*Good buoyancy control, trim and finning technique help preserve visibility in areas with silt deposits. The ability to reverse kick to back out of restrictions where there is no space to turn around is useful.

**Finning skills:

Most cave divers recognize five general rules or contributing factors for safe cave-diving, which were popularized, adapted and became generally accepted from

Most cave divers recognize five general rules or contributing factors for safe cave-diving, which were popularized, adapted and became generally accepted from

Equipment used by cave divers ranges from fairly standard recreational scuba configurations, to more complex arrangements which allow more freedom of movement in confined spaces, extended range in terms of depth and time, allowing greater distances to be covered in acceptable safety, and equipment which helps with navigation, in what are usually dark, and often silty and convoluted spaces.

Scuba configurations which are more often found in cave-diving than in open water diving include independent or manifolded twin cylinder rigs, side-mount harnesses, sling cylinders,

Equipment used by cave divers ranges from fairly standard recreational scuba configurations, to more complex arrangements which allow more freedom of movement in confined spaces, extended range in terms of depth and time, allowing greater distances to be covered in acceptable safety, and equipment which helps with navigation, in what are usually dark, and often silty and convoluted spaces.

Scuba configurations which are more often found in cave-diving than in open water diving include independent or manifolded twin cylinder rigs, side-mount harnesses, sling cylinders,

The

The  The number of sites where

The number of sites where

Atlas of Caves Worldwide

caveatlas.com

Florida Cave & Cavern List

Cave Diving Group, UK, 28 March 2010

Woodville Karst Plain Project

non profit organization about North Florida's underwater cave systems

Todd Kincaid, University of Wyoming

Global Underwater Explorers

non profit organization in Florida, education and exploration; Project Baseline, online spatial database of global underwater conditions

International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery (IUCRR)

International non profit organization registered in Florida

Cave Diving Down Under (Australia)

social media site for cave diving in Australia

Dominican Republic Speleological Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cave Diving

Cave-diving is

Cave-diving is underwater diving

Underwater diving, as a human activity, is the practice of descending below the water's surface to interact with the environment. It is also often referred to as diving, an ambiguous term with several possible meanings, depending on context ...

in water-filled cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as se ...

s. It may be done as an extreme sport, a way of exploring flooded caves for scientific investigation, or for the search for and recovery of divers or, as in the 2018 Thai cave rescue, other cave users. The equipment used varies depending on the circumstances, and ranges from breath hold to surface supplied, but almost all cave-diving is done using scuba equipment

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chri ...

, often in specialised configurations with redundancies such as sidemount

Sidemount is a scuba diving equipment configuration which has scuba sets mounted alongside the diver, below the shoulders and along the hips, instead of on the back of the diver. It originated as a configuration for advanced cave diving, as i ...

or backmounted twinset. Recreational cave-diving is generally considered to be a type of technical diving

Technical diving (also referred to as tec diving or tech diving) is scuba diving that exceeds the agency-specified limits of recreational diving for non- professional purposes. Technical diving may expose the diver to hazards beyond those normal ...

due to the lack of a free surface

In physics, a free surface is the surface of a fluid that is subject to zero parallel shear stress,

such as the interface between two homogeneous fluids.

An example of two such homogeneous fluids would be a body of water (liquid) and the air i ...

during large parts of the dive, and often involves planned decompression stops. A distinction is made by recreational diver training agencies between cave-diving and cavern-diving, where cavern diving is deemed to be diving in those parts of a cave where the exit to open water can be seen by natural light. An arbitrary distance limit to the open water surface may also be specified.

In the United Kingdom, cave-diving developed from the locally more common activity of caving

Caving – also known as spelunking in the United States and Canada and potholing in the United Kingdom and Ireland – is the recreational pastime of exploring wild cave systems (as distinguished from show caves). In contrast, speleology is ...

. Its origins in the United States are more closely associated to recreational scuba diving

Recreational diving or sport diving is diving for the purpose of leisure and enjoyment, usually when using scuba equipment. The term "recreational diving" may also be used in contradistinction to "technical diving", a more demanding aspect of r ...

. Compared to caving and scuba diving, there are relatively few practitioners of cave-diving. This is due in part to the specialized equipment and skill sets required, and in part because of the high potential risks due to the specific environment.

Despite these risks, water-filled caves attract scuba divers, cavers

Caving – also known as spelunking in the United States and Canada and potholing in the United Kingdom and Ireland – is the recreational pastime of exploring wild cave systems (as distinguished from show caves). In contrast, speleology is ...

, and speleologists

Speleology is the scientific study of caves and other karst features, as well as their make-up, structure, physical properties, history, life forms, and the processes by which they form (speleogenesis) and change over time (speleomorphology). ...

due to their often unexplored nature, and present divers

Diver or divers may refer to:

*Diving (sport), the sport of performing acrobatics while jumping or falling into water

*Practitioner of underwater diving, including:

**scuba diving,

**freediving,

**surface-supplied diving,

**saturation diving, a ...

with a technical diving challenge. Underwater caves have a wide range of physical features, and can contain fauna not found elsewhere.

Procedures

The procedures of cave-diving have much in common with procedures used for other types of

The procedures of cave-diving have much in common with procedures used for other types of penetration diving

Underwater diving, as a human activity, is the practice of descending below the water's surface to interact with the environment. It is also often referred to as diving, an ambiguous term with several possible meanings, depending on context ...

. They differ from open-water diving

In underwater diving, open water is unrestricted water such as a sea, lake or flooded quarries. It is the opposite of confined water (usually a swimming pool) where diver training takes place. Open water also means the diver has direct vertical ...

procedures mainly in the emphasis on navigation, gas management, operating in confined spaces, and that the diver is physically constrained from direct ascent to the surface during much of the dive.

As most cave-diving is done in an environment where there is no free surface with breathable air allowing an above-water exit, it is critically important to be able to find the way out before the breathing gas runs out. This is ensured by the use of a continuous guideline between the dive team and a point outside of the flooded part of the cave, and diligent planning and monitoring of gas supplies. Two basic types of guideline are used: permanent lines, and temporary lines. Permanent lines may include a main line starting near the entrance/exit, and side lines or branch lines, and are marked

In linguistics and social sciences, markedness is the state of standing out as nontypical or divergent as opposed to regular or common. In a marked–unmarked relation, one term of an opposition is the broader, dominant one. The dominant defau ...

to indicate the direction along the line to the nearest exit. Temporary lines include exploration lines and jump lines.

Decompression procedures may take into account that the cave diver usually follows a very rigidly constrained and precisely defined route, both into and out of the cave, and can reasonably expect to find any equipment such as drop cylinders temporarily stored along the guideline while making the exit. In some caves, changes of depth of the cave along the dive route will constrain decompression depths, and gas mixtures and decompression schedules can be tailored to take this into account.

Skills

Most open-water diving skills apply to cave-diving, and there are additional skills specific to the environment, and to the chosen equipment configuration.

*Good buoyancy control, trim and finning technique help preserve visibility in areas with silt deposits. The ability to reverse kick to back out of restrictions where there is no space to turn around is useful.

**Finning skills:

Most open-water diving skills apply to cave-diving, and there are additional skills specific to the environment, and to the chosen equipment configuration.

*Good buoyancy control, trim and finning technique help preserve visibility in areas with silt deposits. The ability to reverse kick to back out of restrictions where there is no space to turn around is useful.

**Finning skills: Frog kick

Finning techniques are the skills and methods used by swimmers and underwater divers to propel themselves through the water and to maneuver when wearing swimfins. There are several styles used for propulsion, some of which are more suited to pa ...

, which avoids up- and downward directed vortices and are less likely to disturb silt on the bottom or loose material on the ceiling, and modified frog kick, a version which is more suited to narrow spaces; modified flutter kick

The flutter kick is a kicking movement used in both swimming and calisthenics.

Swimming

In swimming strokes such as the front crawl or backstroke, the primary purpose of the flutter kick is not propulsion but keeping the legs up and in the shad ...

, a version of flutter kick which minimises downward directed vortices; back kick, which produces thrust towards the feet, used to move backwards along the long axis of the diver, and helicopter turns, which rotate the diver on the spot around a vertical axis, using lower leg and ankle movements.

*The ability to navigate in total darkness using the guideline to find the way out is a safety critical emergency skill. Line management skills required for cave-diving include laying and recovering guide lines using a reel, tie-offs, the use of a jump line to cross gaps or find a lost guide line in silted out conditions, identifying the direction along the guideline leading to the exit, and the skills of dealing with a break in a guideline.

*Emergency skills for dealing with gas supply problems are complicated by the possibility of the emergency occurring in a confined space and low visibility or darkness, and at a considerable horizontal distance from a free surface to the atmosphere.

*Communicating by touch and light signals.

*Providing and receiving emergency breathing gas while swimming through narrow spaces.

Line management

The essential cave-diving procedure is navigation using a guide line. This includes laying and marking line, following line and interpreting line markers, avoiding entanglement, recovering from entanglement, maintaining and repairing line, finding lost line, jumping gaps, and recovering line, any of which may need to be done in zero visibility, total darkness, tight confined spaces or a combination of these conditions. *Laying a cave line: the procedure of running line (unreeling line under light tension as one advances) to avoid snagging on the diver and so that it runs fairly straight between s, placing the line so it can all be seen and reached, so it can be followed in good or bad visibility, avoiding s, and securing the line sufficiently at suitable places to keep it in position. **Making placements - securing the guideline as it is being run and the choice of primary and secondary tie offs. **Temporary line – line that is laid on the way into parts of a cave without permanent line, and recovered to the reel on the way out. **Permanent line – line that is thicker, and therefore easier to see, stronger, and more abrasion resistant, and more securely fastened, intended to be left in place for use by other divers. It may be secured to placements at closer intervals to facilitate finding the other end and reconnection in case of a break. It is not recovered during exit, and will generally be marked. *Marking line: Permanent line is marked to indicate the direction to the nearest exit, and to indicate where dive teams have passed but have not yet returned by looping the line onto a line marker, ensuring that a directional marker points in the correct direction, and that all markers are sufficiently securely attached, while remaining easily removable if temporary. **Directional markers - cave arrows used to indicate the way out along the line. **Personal markers – cookies – temporary markers to indicate that a diver has passed beyond a point but has not returned yet, particularly where the group leaves the permanent line or makes a jump to a secondary permanent (branch) line. A personal directional marker may be attached to a line to indicate that the owner has gone in that direction, which can happen after divers are separated if one finds the line but not the other divers, and decides to exit independently. *Following a line – the skills of navigating back out of a cave using the line as a guide, particularly in the dark and low visibility. *Finding a lost line: although cave-diving procedures are intended to minimize the risk of losing the guide line, it can happen, and as the chance of finding one's way out without the line are drastically reduced, losing the line is considered a life-threatening situation, and the diver must be competent in the methods for relocating the line in all reasonably foreseeable circumstances, which include a bad silt-out, total darkness, and loss of contact with the other divers in the team. Methods of search should prevent the diver from drifting away from the vicinity of the line, so the start position for the search should be secured by tying off a search line. In principle, if the diver feels their way around the cross section of the cave orthogonal to the line direction until they get back to the starting point, the guideline should be either found directly, or be within the loop of the search line, but even this is not guaranteed to work, as the shape of the cave and limited breathing gas supplies could make this impossible. *Fixing a line break, This requires the ability to tie reliable knots, which may have to be done in bad visibility. It also require the diver to find the other end of the break. On the way into a cave a line break is an inconvenience, as if the other side cannot be found, the divers can still find their way out. On the way out a line break is a life-threatening emergency until the other end is found, as gas supply is limited and there is no infallible way to find the other end while there is enough gas to complete the exit. *Jumping a gap to a branch line – this involves tying off to the permanent line in a way that is unlikely to come loose, but may be released quickly on the return. Passing a loop on the end of the jump line round the permanent line and over the reel is a standard method. A tag on the end of the loop helps release it quickly. This method cannot be inadvertently released by other divers following the main line. *Recovering temporary line – this is done by the last diver in line on the way out, so the others can follow the line out of the cave, even in reduced visibility, without risking losing the line. They may prepare the line for the reel operator, by releasing tie-offs, which cuts down on delays. In an emergency exit the reel and line may be temporarily abandoned, as it can be retrieved later. The reel operator keeps a light tension on the line and tries to keep it evenly distributed over the width of the reel while winding in. The divers further ahead on the line can feel the presence of others behind them by line tension and small movements of the line as it is reeled in.Lost line

Losing the guide line in a cave is a potentially life-threatening emergency. While following recommended best practice makes it highly unlikely that a diver will lose the line, it can and does happen, and there are procedures which will usually work to find it again. Any reliable information on where the diver is likely to be relative to the last known position of the line may be critical, and the procedure of choice will depend on what is reliably known. In all situations, the diver will attempt to stabilise the situation and avoid getting further lost, and make a thorough visual check in all directions from where they are at the time, taking into account the possibility of the line being in a line trap. If the diver has not also separated from their buddy, the buddy may know where the line is, and can be asked, and if the diver is separated from their buddy, the buddy may be at the line, and the buddy's light may be visible. Stabilising the position is generally done by finding the nearest feasible tie-off point and securely tying off a search line. The direction of the guide line when last seen should be known, and therefore the direction the diver was swimming in before losing the line. If the diver was neutrally buoyant while following the line, the approximate depth can be reconstructed by finding the depth of neutral buoyancy again, without adjusting inflation of BCD or dry suit. Unless the line was lost by the diver not noticing a change of direction, it is likely to be at much the same depth, in much the same direction, and at a similar lateral and vertical distance as when last seen, making it logical to try that direction first. While swimming towards the estimated position of the line and slowly paying out search line, the diver will search visually, and in low visibility or darkness, also by feel, making arm sweeps across the expected direction of the line, while defending the head from impact with the other arm. The distance swum towards the estimated position of the lost line can be measured by the spacing and number of knots paid out on the search line. If the search fails, the diver will return to the tie off and try again in the next best guess for the direction the line may be. The diver may also choose to try a different search method. The best search method for any given situation will depend on the water conditions, the layout of the section of cave, the way the line was laid, the situational knowledge and skills of the diver, and the equipment available – a method that would be ideal for one situation might not work at all for another. If the line is found, but not the other divers, the diver can tie off their search reel to the guide line as an indicator to other members of the team that they were lost but have found the guide line, and indicate the direction that they intend to proceed along the guideline with a personal directional marker so that others who see it while searching for the lost diver will know whether the diver chose the right direction to exit the cave.Lost buddy

This is generally the converse situation to the lost guide line, in that the diver loses contact with their buddy or team but remains in contact with the guide line, so is not themself lost. Their first priority is to not get lost or disorientated, and in furtherance of this aim would attach a directional line marker to the guide line indicating the direction to the exit before starting a search. The search line can be tied to the directional maker to prevent it from sliding along the line during the search. The direction for the search would depend on the layout of that part of the cave, and where the missing diver should have been in the group. The search party must consider their own safety first, regarding how much gas they can afford to use in a search, which will depend on the stage of the dive when the diver is noticed to be missing. When searching in darkness, the searches should periodically turn off their lights as this will allow them to see the lost diver's light more easily.Gas planning and management

Gas planning is the aspect ofdive planning

Dive planning is the process of planning an underwater diving operation. The purpose of dive planning is to increase the probability that a dive will be completed safely and the goals achieved. Some form of planning is done for most underwater di ...

which deals with the calculation or estimation of the amounts and mixtures of gases to be used for a planned dive profile

A dive profile is a description of a diver's pressure exposure over time. It may be as simple as just a depth and time pair, as in: "sixty for twenty," (a bottom time of 20 minutes at a depth of 60 feet) or as complex as a second by second gra ...

. It usually assumes that the dive profile, including decompression, is known, but the process may be iterative, involving changes to the dive profile as a consequence of the gas requirement calculation, or changes to the gas mixtures chosen. Use of calculated reserves based on planned dive profile and estimated gas consumption rates rather than an arbitrary pressure based on a fraction of the initial gas supply is sometimes referred to as rock bottom gas management. The purpose of gas planning is to ensure that for all reasonably foreseeable contingencies, the divers of a team have sufficient breathing gas to safely return to a place where more breathing gas is available. In almost all cases this will be the surface.

Gas planning includes the following aspects:

* Choice of breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed h ...

es to suit the depth at which they will be used,

* Choice of Scuba configuration, to conveniently carry the gas, or store it at stage points along the route

* Estimation of gas quantities required for the planned dive, including , , and decompression gases, as appropriate to the profile.

* Estimation of gas quantities for reasonably foreseeable contingencies. Under stress it is likely that a diver will increase breathing rate and decrease swimming speed. Both of these lead to a higher gas consumption during an emergency exit or ascent.

* Choice of cylinders

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an in ...

to carry the required gases. Each cylinder volume and working pressure must be sufficient to contain the required quantity of gas.

* Calculation of the pressures for each of the gases in each of the cylinders to provide the required quantities.

* Specifying the critical pressures of relevant gas mixtures for appropriate stages (waypoints) of the planned dive profile (gas matching

Scuba gas planning is the aspect of dive planning and of gas management which deals with the calculation or estimation of the amounts and mixtures of gases to be used for a planned dive. It may assume that the dive profile, including decompre ...

).

The primary breathing apparatus may be open circuit scuba or rebreather, and bailout may also be open circuit or rebreather. Emergency gas may be shared among the team members, or each diver may carry their own, but in all cases each diver must be able to bail out onto a gas supply of their own for long enough to get to the next planned source of emergency gas. If for any reason this situation no longer applies, there is a single point of critical failure, and the risk becomes unacceptable, so the dive should be turned.

Gas management also includes the blending, filling, analysing, marking, storage, and transportation of gas cylinders for a dive, and the monitoring and switching of breathing gases during a dive, and the provision of emergency gas to another member of the dive team. The primary aim is to ensure that everyone has enough to breathe of a gas suitable for the current depth at all times, and is aware of the gas mixture in use and its effect on decompression obligations and oxygen toxicity risk.

Gas management rules of thumb

Therule of thirds

The rule of thirds is a "rule of thumb" for composing visual images such as designs, films, paintings, and photographs.

The guideline proposes that an image should be imagined as divided into nine equal parts by two equally spaced horizontal lin ...

for gas management is a rule of thumb used by divers to plan dives so they have enough breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed h ...

remaining in their diving cylinder

A diving cylinder or diving gas cylinder is a gas cylinder used to store and transport high pressure gas used in diving operations. This may be breathing gas used with a scuba set, in which case the cylinder may also be referred to as a scu ...

at the end of the dive to be able to complete the dive safely. This rule mostly applies to diving in overhead environments, such as caves and wrecks, where a direct ascent to the surface is impossible and the divers must return the way they came.

For divers following the rule, one third of the gas supply is planned for the outward journey, one third is for the return journey and one third is a safety reserve. However, when diving with a buddy with a higher breathing rate or a different volume of gas, it may be necessary to set one third of the buddy's gas supply as the remaining 'third'. This means that the turn point to exit is earlier, or that the diver with the lower breathing rate carries a larger volume of gas than he alone requires.

A different option for penetration dives is the Half + 15 bar (half + 200 psi) method, in which the contingency gas for the stage is carried in the primary cylinders. Some divers consider this method to be the most conservative when multi-staging. If all goes to plan when using this method, the divers surface with stages nearly empty, but with all the contingency gas still in their primary cylinders. With a single stage drop, this means the primary cylinders will still be about half-full.

Training

Cave-diving training includes equipment selection and configuration, guideline protocols and techniques, gas management protocols, communication techniques, propulsion techniques, emergency management protocols, and psychological education. Cave diver training also stresses the importance of risk management and cave conservation ethics. Most training systems offer progressive stages of education and certification. *Cavern training covers the basic skills needed to enter the overhead environment. Training will generally consist of gas planning, propulsion techniques needed to deal with the silty environments in many caves, reel and handling, and communication. Once certified as a cavern diver, a diver may undertake cavern diving with a cavern or cave certified "buddy", as well as continue into cave-diving training. *Introduction into cave training builds on the techniques learned during cavern training and includes the training needed to penetrate beyond the cavern zone and working with permanent guidelines that exist in many caves. Once intro to cave certified, a diver may penetrate much further into a cave, usually limited by 1/3 of a single cylinder, or in the case of a basic cave certification, 1/6 of double cylinders. An intro cave diver is usually not certified to do complex navigation. *Apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

cave training serves as the transition from intro to full certification and includes the training needed to penetrate deep into caves working from permanent guide lines as well as limited exposure to side lines that exist in many caves. Training covers complex dive planning and decompression procedures used for longer dives. Once apprentice certified, a diver may penetrate much further into a cave, usually limited by 1/3 of double cylinders. An apprentice diver is also allowed to do a single jump or gap (a break in the guideline from two sections of mainline or between mainline and sideline) during the dive. An apprentice diver typically has one year to finish full cave or must repeat the apprentice stage.

*Full cave training serves as the final level of basic training and includes the training needed to penetrate deep into the cave working from both permanent guidelines and sidelines, and may plan and complete complex dives deep into a system using decompression to stay longer. Once cave certified, a diver may penetrate much further into a cave, usually limited by 1/3 of double cylinders. A cave diver is also certified as competent to do multiple jumps or gaps (a break in the guideline from two sections of mainline or between mainline and sideline) during the dive.

* Further training may be available in skills for cave surveying and mapping.

Hazards

Cave-diving is one of the most challenging and potentially dangerous kinds of diving and presents many hazards. Cave-diving is a form ofpenetration diving

Underwater diving, as a human activity, is the practice of descending below the water's surface to interact with the environment. It is also often referred to as diving, an ambiguous term with several possible meanings, depending on context ...

, meaning that in an emergency a diver cannot swim vertically to the surface due to the cave's ceilings, and so must swim the entire way back out. The underwater navigation through the cave system may be difficult and exit routes may be at a considerable distance, requiring the diver to have sufficient breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed h ...

to make the journey. The dive may also be deep, resulting in potential deep diving

Deep diving is underwater diving to a depth beyond the norm accepted by the associated community. In some cases this is a prescribed limit established by an authority, while in others it is associated with a level of certification or training, an ...

risks.

Visibility can vary from nearly unlimited to low, or non-existent, and can go from very good to very bad in a single dive. While a less-intensive kind of diving called cavern diving does not take divers beyond the reach of natural light (and typically no deeper than ), and penetration not further than , true cave-diving can involve penetrations of many thousands of feet, well beyond the reach of sunlight. The level of darkness experienced creates an environment impossible to see in without an artificial source of light even if the water is clear. Caves often contain sand, mud, clay, silt, or other sediment that can further reduce underwater visibility in seconds when stirred up.

The water in caves can have strong flow

Flow may refer to:

Science and technology

* Fluid flow, the motion of a gas or liquid

* Flow (geomorphology), a type of mass wasting or slope movement in geomorphology

* Flow (mathematics), a group action of the real numbers on a set

* Flow (psyc ...

. Most caves flooded to the surface at the cave mouth are either springs or siphons. Springs have out-flowing currents, where water is coming up out of the Earth and flowing out across the land's surface. Siphons have in-flowing currents where, for example, an above-ground river is going underground. Some caves are complex and have some tunnels with out-flowing currents, and other tunnels with in-flowing currents. Inflowing currents can cause serious problems for the diver, as they make the exit more difficult, and the diver is carried to spaces that are unfamiliar and may be dangerous, while outflowing currents generally make the exit quicker and the diver is carried through places they have been before and can be prepared for difficult areas.

Cave-diving has been perceived as one of the more deadly sports in the world. This perception may be exaggerated because the majority of divers who have died in caves have either not undergone specialized training or have had inadequate equipment for the environment. Some cave divers have suggested that cave-diving is statistically much safer than recreational diving due to the much larger barriers imposed by experience, training and equipment cost, but there is no definitive statistical evidence for this claim.

There is no reliable worldwide database listing all cave-diving fatalities. Such fractional statistics as are available, however, suggest that few divers have died while following accepted protocols and while using equipment configurations recognized as acceptable by the cave-diving community. In the very rare cases of exceptions to this rule there have typically been unusual circumstances.

Safety

Most cave divers recognize five general rules or contributing factors for safe cave-diving, which were popularized, adapted and became generally accepted from

Most cave divers recognize five general rules or contributing factors for safe cave-diving, which were popularized, adapted and became generally accepted from Sheck Exley

Sheck Exley (April 1, 1949 – April 6, 1994) was an American cave diver. He is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of cave diving, and he wrote two major books on the subject: '' Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival'' and ''Caverns M ...

's 1979 publication ''Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival''. In this book, Exley included accounts of actual cave-diving accidents, and followed each one with a breakdown of what factors contributed to the accident. Despite the unique circumstances of each individual accident, Exley found that at least one of a small number of major factors contributed to each one. This technique for breaking down accident reports and finding common causes among them is now called ''accident analysis

Accident analysis is carried out in order to determine the cause or causes of an accident (that can result in single or multiple outcomes) so as to prevent further accidents of a similar kind. It is part of ''accident investigation or incident inv ...

'', and is taught in introductory cave-diving courses. Exley outlined a number of these resulting cave-diving rules, but today these five are the most recognized:

*Training: A safety conscious cave diver does not intentionally exceed the scope of their training. Cave-diving is normally taught in stages, each successive stage focusing on more complex aspects of cave-diving. Each stage of training is intended to be reinforced with actual cave-diving experience to develop competence before starting training at a more complex level. Accident analysis of cave-diving fatalities has shown that academic training without sufficient real world experience is not always enough in the event of an underwater emergency. By systematically building experience the diver can develop the confidence, motor skills and reflexes to remain calm and apply the appropriate procedures in an emergency. An inexperienced diver is more likely to panic than an experienced diver when confronted with a similar situation, all other factors being equal. Experience in dealing successfully with real or simulated problems is of the greatest value, experience of dives where nothing goes wrong reinforces the skills used, but not the skills that were not needed but might be critical in an emergency. When trained to the highest available level, further competence can be developed by practice and gradual extension of range of experience.

*Guide line

A distance line, penetration line, cave line or guide line is an item of diving equipment used by scuba divers as a means of returning to a safe starting point in conditions of low visibility, water currents or where pilotage is difficult. They ...

: A continuous guide line is maintained at all times between the leader of a dive team and a fixed point selected outside the cave entrance in open water. Often this line is tied off a second time as a backup directly inside the cavern zone. As the dive leader lays the guideline they take great care to ensure there is appropriate tension on the line, and that it does not go into line traps, tying off the line as necessary to keep it leading through a clear route. Other team members remain between the lead diver and the exit, in easy reach of the line at all times. If a silt out

A silt out or silt-out is a situation when underwater visibility is rapidly reduced to functional zero by disturbing fine particulate deposits on the bottom or other solid surfaces. This can happen in scuba and surface supplied diving, or in ROV ...

occurs, divers can find the line and follow it back to the cave entrance. Failure to use a continuous guide line to open water is cited as the most frequent cause of fatality among untrained, non-certified divers who venture into caves. Greater care to avoid line traps is required for laying permanent line, and more frequent tie-offs would be expected, as a permanent line is more susceptible to breaking over time.

*Depth rules: Gas consumption, nitrogen narcosis and decompression obligation increase with depth, and the effects of nitrogen narcosis

Narcosis while diving (also known as nitrogen narcosis, inert gas narcosis, raptures of the deep, Martini effect) is a reversible alteration in consciousness that occurs while diving at depth. It is caused by the anesthetic effect of certain ga ...

may be more critical in a cave due to the high task loading and presence of combinations of hazards. Cave divers are advised not to dive to depths exceeding the planned depth and the applicable range of their equipment and the breathing gases in use, and to keep in mind this effective difference between open water depth and cave depth. Excessive depth is frequently cited as a contributory factor in fatal incidents involving fully trained cave divers.

* Breathing gas management: The breathing gas supply must last the diver until out of the overhead environment. There are several strategies for gas management. The most common protocol is the 'rule of thirds

The rule of thirds is a "rule of thumb" for composing visual images such as designs, films, paintings, and photographs.

The guideline proposes that an image should be imagined as divided into nine equal parts by two equally spaced horizontal lin ...

,' in which one third of the initial gas supply is used for ingress, one third for egress, and one third to support another team member in the case of an emergency. This is a very simple method, but is not always sufficient. UK practice is to adhere to the rule of thirds, but with an added emphasis on keeping depletion of the separate air systems "balanced", so that the complete loss of any single gas supply will still leave the diver with sufficient gas to return safely. The rule of thirds makes no allowance for increased air consumption that the stress caused by the loss of an air system may induce. Dissimilar tank sizes among the divers are also not allowed for by the rule of thirds, and a sufficient reserve should be calculated for each dive. UK practice is to assume that each diver is completely independent, as in a typical UK sump there is usually nothing that a buddy can do to assist a diver in trouble. Most UK cave divers dive solo. US sump divers follow a similar protocol. The rule of thirds was devised as an approach to diving Florida's caves – they typically have high outflow currents, which help to reduce air consumption when exiting. In a cave system with little or no outflow it is prudent to reserve more air than is provided by the rule of thirds.

*Lights: Each cave diver should have at least three independent sources of light. One is considered the primary and is intended for general use during the dive. The others are considered backup lights and may be lower powered as they are not intended for exploration. Each light must have an expected burn time of at least the planned duration of the dive. If any diver loses light function so that they have fewer than three working lights, protocol requires that the dive be aborted for all members of the dive team and that they immediately start the exit.

Most cave-diving fatalities are due to running out of gas before reaching the exit. This is often the direct consequence of getting lost, whether the guide line is found again or not, and whether the visibility deteriorates, lights fail, or someone panics. On rare occasions equipment failure is unrecoverable, or a diver becomes inextricably trapped, seriously injured, incapacitated by using an unsuitable gas for the depth, or swept away by strong flow. Getting lost means separation from the continuous guide line to the exit, and not knowing the direction to the exit.

Some cave divers are taught to remember the five key components with the mnemonic

A mnemonic ( ) device, or memory device, is any learning technique that aids information retention or retrieval (remembering) in the human memory for better understanding.

Mnemonics make use of elaborative encoding, retrieval cues, and imager ...

: "''The Good Divers Always Live''" (training, guide, depth, air, light).

In recent years new contributing factors were considered after reviewing accidents involving solo diving, diving with incapable dive partners, video or photography in caves, complex cave dives and cave-diving in large groups. With the establishment of technical diving, the use of mixed gases—such as trimix for bottom gas, and nitrox and oxygen for decompression—reduces the margin for error. Accident analysis suggests that breathing the wrong gas for the depth or not analyzing the breathing gas properly has also led to cave-diving accidents.

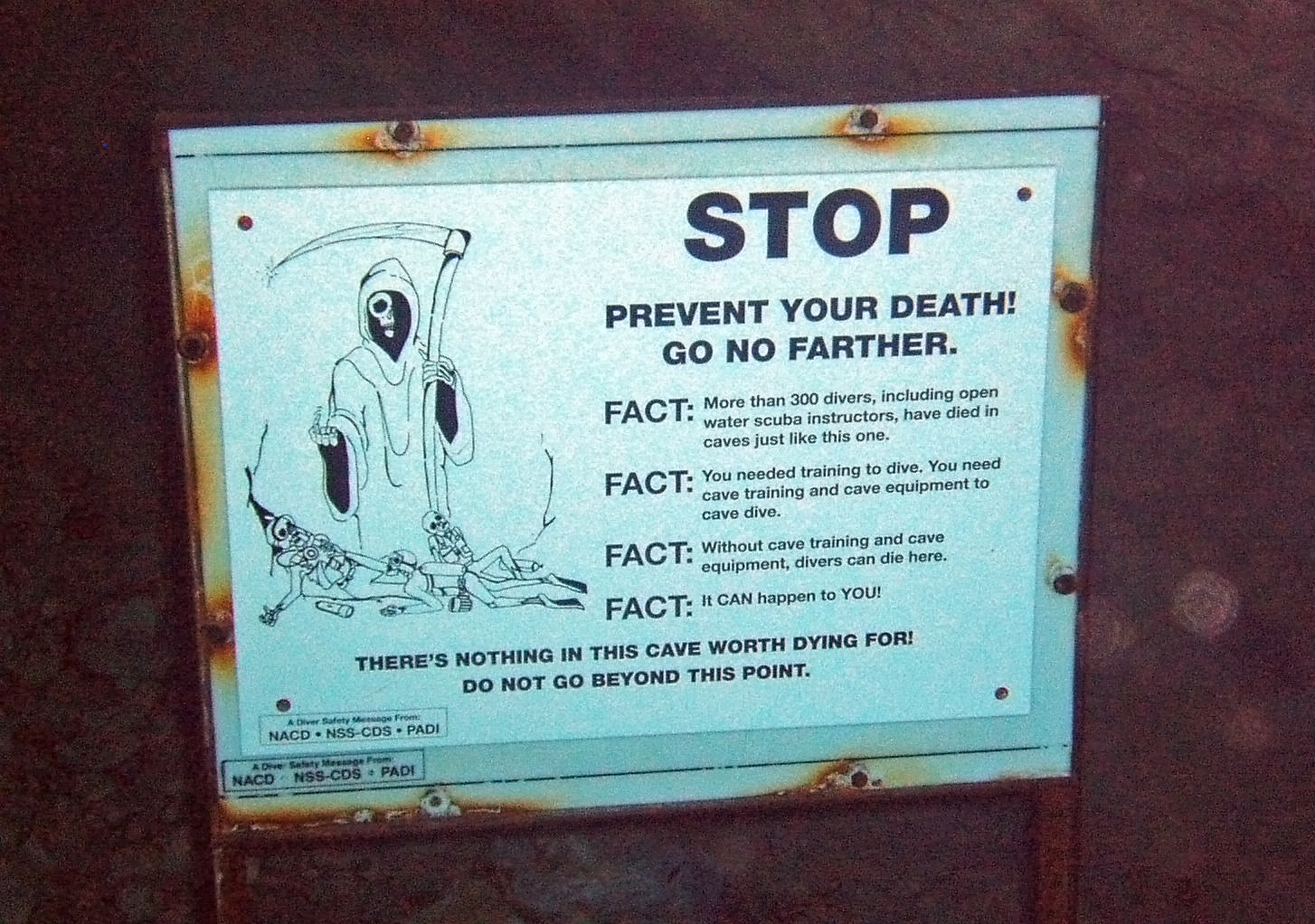

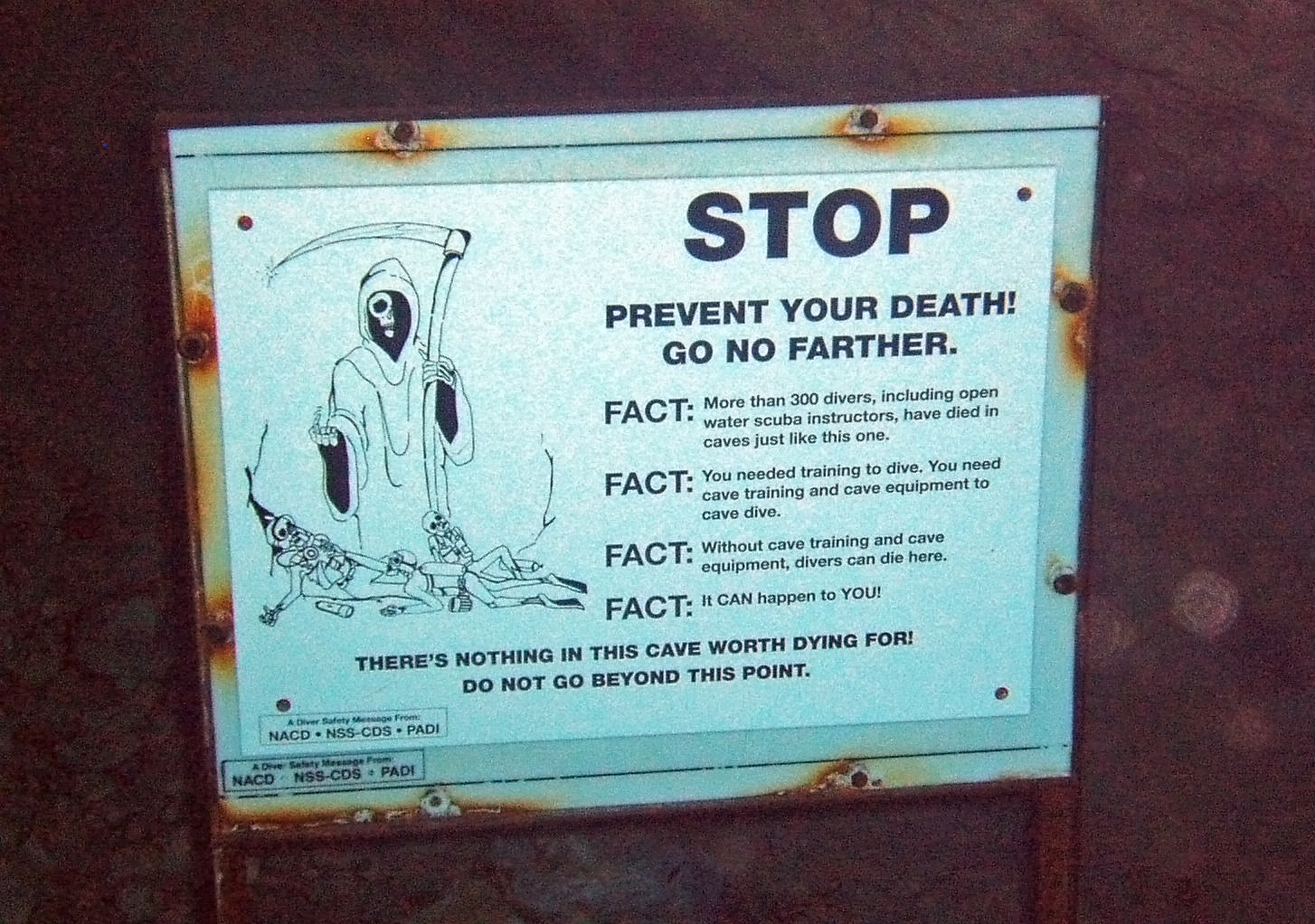

Cave-diving requires a variety of specialized procedures, and divers who do not correctly apply these procedures may significantly increase the risk to the members of their team. The cave-diving community works hard to educate the public on the risks they assume when they enter water-filled caves. Warning signs with the likenesses of the Grim Reaper

Death is frequently imagined as a personified force. In some mythologies, a character known as the Grim Reaper (usually depicted as a berobed skeleton wielding a scythe) causes the victim's death by coming to collect that person's soul. Other b ...

have been placed just inside the openings of many popular caves in the US and Mexico, and others have been placed in nearby parking lots and local dive shops.

Many cave-diving sites around the world include open-water basins, which are popular open-water diving sites. The management of these sites try to minimize the risk of untrained divers being tempted to venture inside the cave systems. With the support of the cave-diving community, many of these sites enforce a "no-lights rule" for divers who lack cave training—they may not carry any lights into the water with them. It is easy to venture into an underwater cave with a light and not realize how far away from the entrance (and daylight) one has swum; this rule is based on the theory that, without a light, divers will not venture beyond daylight.

In the early phases of cave-diving the analysis shows that 90% of accidents were ''not'' trained cave divers; from the 2000s on the trend has reversed to 80% of accidents involving trained cave divers. Modern cave divers' capability and available technology allows divers to venture well beyond traditional training limits and into actual exploration. The result is an increase of cave-diving accidents, in 2011 the yearly average of 2.5 fatalities a year tripled. In 2012 fatalities reached the highest annual rate to that date at over 20.

As response to the increase in fatalities during the years 2010 onwards, the International Diving Research and Exploration Organization (IDREO) was created in order to "bring awareness of the current safety situation of Cave Diving" by listing current worldwide accidents by year and promoting a community discussion and analysis of accidents through a "Cave Diver Safety Meeting" held annually.

Equipment

Equipment used by cave divers ranges from fairly standard recreational scuba configurations, to more complex arrangements which allow more freedom of movement in confined spaces, extended range in terms of depth and time, allowing greater distances to be covered in acceptable safety, and equipment which helps with navigation, in what are usually dark, and often silty and convoluted spaces.

Scuba configurations which are more often found in cave-diving than in open water diving include independent or manifolded twin cylinder rigs, side-mount harnesses, sling cylinders,

Equipment used by cave divers ranges from fairly standard recreational scuba configurations, to more complex arrangements which allow more freedom of movement in confined spaces, extended range in terms of depth and time, allowing greater distances to be covered in acceptable safety, and equipment which helps with navigation, in what are usually dark, and often silty and convoluted spaces.

Scuba configurations which are more often found in cave-diving than in open water diving include independent or manifolded twin cylinder rigs, side-mount harnesses, sling cylinders, rebreathers

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen is ...

and backplate and wing

A backplate and wing (often abbreviated as BP&W or BP/W) is a type of scuba harness with an attached buoyancy compensation device (BCD) which establishes neutral buoyancy underwater and positive buoyancy on the surface. Unlike most other BCDs ...

harnesses. Bill Stone designed and used epoxy composite tanks for exploration of the San Agustín and Sistema Huautla

Sistema Huautla is a cave system in the Sierra Mazateca mountains of the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. it was the deepest cave system in the Western Hemisphere, from top to bottom, with over 55 miles of mapped passageways.

Location

Sis ...

caves in Mexico to decrease the weight for dry sections and vertical passages.

Stage cylinders are cylinders which are used to provide gas for a portion of the penetration. They may be deposited on the bottom at the guideline on preparation dives, to be picked up for use during the main dive, or may be carried by the divers and dropped off at the line during the penetration to be retrieved on the way out.

One of the high risk hazards of cave-diving is getting lost in the cave. The use of guide lines is the standard mitigation for this risk. Guide lines may be permanent or laid and recovered during the dive, using cave reels to deploy and recover the line. Permanent branch lines may be laid with a gap between the start of the branch line and the nearest point on the main line. Line used for this purpose is known as cave line. Gap spools with a relatively short line are commonly used to make the jump

Jumping is a form of locomotion or movement in which an organism or non-living (e.g., robotic) mechanical system propels itself through the air along a ballistic trajectory.

Jump or Jumping also may refer to:

Places

* Jump, Kentucky or Jump S ...

.

Line arrows are used to point towards the nearest exit, and cookies

A cookie is a baked or cooked snack or dessert that is typically small, flat and sweet. It usually contains flour, sugar, egg, and some type of oil, fat, or butter. It may include other ingredients such as raisins, oats, chocolate chips, nuts ...

are used to indicate use of a line by a team of divers.

Silt screws are short lengths of rigid tube (usually plastic) with one sharpened end and a notch or slot at the other end to secure the line, which are pushed into the silt or detritus of the cave floor as a place to tie off a guideline when no suitable natural tie-off points are available.

A simple plastic helmet, such as those used in water sports like whitewater kayaking, is good protection in case of accidental contact with the cave ceiling or stalactites.

Diver propulsion vehicle

A diver propulsion vehicle (DPV), also known as an underwater propulsion vehicle, sea scooter, underwater scooter, or swimmer delivery vehicle (SDV) by armed forces, is an item of diving equipment used by scuba divers to increase range under ...

s, or Scooters, are sometimes used to extend the range by reducing the work load on the diver and allowing faster travel in open sections of cave. Reliability of the diver propulsion vehicle is very important, as a failure could compromise the ability of the diver to exit the cave before running out of gas. Where this is a significant risk, divers may tow a spare scooter.

Dive light

A dive light is a light source carried by an underwater diver to illuminate the underwater environment. Scuba divers generally carry self-contained lights, but surface supplied divers may carry lights powered by cable supply .

A dive light is ...

s are critical safety equipment, as it is dark inside caves. Each diver generally carries a primary light, and at least one backup light. A minimum of three lights is recommended. The primary light should last the planned duration of the dive, as should each of the backup lights.

Cavern diving

Cavern diving is an arbitrarily defined, limited scope activity of diving in the naturally illuminated part of underwater caves, where the risk of getting lost is small, as the exit can be seen, and the equipment needed is reduced due to the limited distance to surface air. It is defined as a recreational diving activity as opposed to a technical diving activity on the grounds of low risk and basic equipment requirements.History

Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus). Th ...

, co-inventor of the first commercially successful open circuit scuba equipment

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chri ...

, was the world's first open circuit scuba cave diver. However, many cave divers penetrated caves prior to the advent of scuba with surface supplied breathing apparatus through the use of umbilical hoses and compressors. SCUBA diving in all its forms, including cave-diving, has advanced in earnest since Cousteau introduced the Aqua-Lung

Aqua-Lung was the first open-circuit, self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (or "scuba") to achieve worldwide popularity and commercial success. This class of equipment is now commonly referred to as a twin-hose diving regulator, or dem ...

in 1943.

Two regions have had particular influence on cave-diving techniques and equipment due to their very different cave-diving environments. These are the United Kingdom, and the United States, mainly Florida.

UK history

Cave Diving Group

The Cave Diving Group (CDG) is a United Kingdom-based diver training organisation specialising in cave diving.

The CDG was founded in 1946 by Graham Balcombe, making it the world's oldest continuing diving club. Graham Balcombe and Jack Shep ...

(CDG) was established informally in the United Kingdom in 1935 to organise training and equipment for the exploration of flooded caves in the Mendip Hills

The Mendip Hills (commonly called the Mendips) is a range of limestone hills to the south of Bristol and Bath in Somerset, England. Running from Weston-super-Mare and the Bristol Channel in the west to the Frome valley in the east, the hills o ...

of Somerset. The first dive was made by Jack Sheppard

Jack Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724), or "Honest Jack", was a notorious English thief and prison escapee of early 18th-century London.

Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter but took to theft and burglary in ...

on 4 October 1936,

using a home-made drysuit surface fed from a modified bicycle pump, which allowed Sheppard to pass Sump 1 of Swildon's Hole

Swildon's Hole is an extensive cave in Priddy, Somerset. At in length, it is the longest cave on the Mendip Hills. It has been found to be connected to Priddy Green Sink and forms part of the Priddy Caves Site of Special Scientific Interest (S ...

. Swildon's is an upstream feeder to the Wookey Hole

Wookey Hole is a village in Somerset, England. It is the location of the Wookey Hole show caves.

Location

Wookey Hole is located in the civil parish of St Cuthbert Out, in Mendip District. It is one mile north-west of the city of Wells, and l ...

resurgence system. The difficulty of access to the sump in Swildon's prompted operations to move to the resurgence, and the larger cave there allowed use of standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

which was secured from the Siebe Gorman

Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd was a British company that developed diving equipment and breathing equipment and worked on commercial diving and marine salvage projects. The company advertised itself as 'Submarine Engineers'. It was founded by A ...

company. In UK cave-diving, the term " Sherpa" was used without irony for the people who carry the diver's gear although this has gone out of fashion; support is now more normally used, and before the development of SCUBA equipment such undertakings could be monumental operations.

Diving in the spacious third chamber of Wookey Hole led to a rapid series of advances, each of which was dignified by being given a successive number, until an air surface was reached at what is now known as "Chamber 9." Some of these dives were broadcast live on BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

radio, which must have been a quite surreal experience for both diver and audience.

standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

could be used is clearly limited and there was little further progress before the outbreak of World War II reduced the caving community considerably. However, the rapid development of underwater warfare through the war made a lot of surplus equipment

Equipment most commonly refers to a set of tools or other objects commonly used to achieve a particular objective. Different job

Work or labor (or labour in British English) is intentional activity people perform to support the needs and ...

available. The CDG re-formed in 1946 and progress was rapid. Typical equipment at this time was a frogman rubber diving suit for insulation (water temperature in the UK is typically 4 °C), an oxygen diving cylinder

A diving cylinder or diving gas cylinder is a gas cylinder used to store and transport high pressure gas used in diving operations. This may be breathing gas used with a scuba set, in which case the cylinder may also be referred to as a scu ...

, soda lime

Soda lime is a mixture of NaOH and CaO chemicals, used in granular form in closed breathing environments, such as general anaesthesia, submarines, rebreathers and recompression chambers, to remove carbon dioxide from breathing gases to prevent ...

absorbent canister and counter-lung comprising a rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen i ...

air system and an "AFLOLAUN", meaning "Apparatus For Laying Out Line And Underwater Navigation." The AFLOLAUN consisted of lights, line-reel, compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

, notebook (for the survey), batteries, and more.

Progress was typically by "bottom walking", as this was considered less dangerous than swimming (note the absence of buoyancy controls). The use of oxygen put a depth limit on the dive, which was considerably compensated by the extended dive duration. This was the normal diving equipment and methods until approximately 1960 when new techniques using wetsuits (which provide both insulation and buoyancy ), twin open-circuit SCUBA air systems the development of side mounting cylinders, helmet-mounted lights and free-swimming with fins. The increasing capacity and pressure rating of air bottles also extended dive durations.

US history

In the 1970s, cave-diving greatly increased in popularity among divers in the United States. However, there were very few experienced cave divers and almost no formal classes to handle the surge in interest. The result was a large number of divers trying to cave dive without any formal training. This resulted in more than 100 fatalities over the course of the decade. The state of Florida came close to banning SCUBA diving around the cave entrances. The cave-diving organizations responded to the problem by creating training programs and certifying instructors, in addition to other measures to try to prevent these fatalities. This included posting signs, adding no-lights rules, and other enforcements. In the United States,Sheck Exley

Sheck Exley (April 1, 1949 – April 6, 1994) was an American cave diver. He is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of cave diving, and he wrote two major books on the subject: '' Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival'' and ''Caverns M ...

was a pioneering cave diver who first explored many underwater cave systems in Florida, and many throughout the US and the world. On 6 February 1974, Exley became the first chairman of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society

The National Speleological Society (NSS) is an organization formed in 1941 to advance the exploration, conservation, study, and understanding of caves in the United States. Originally headquartered in Washington D.C., its current offices are in ...

.

Since the 1980s, cave-diving education has greatly reduced diver fatalities, and it is now rare for an agency trained diver to perish in an underwater cave. Also in the 1980s, refinements were made to the equipment used for cave-diving, most importantly better lights with smaller batteries. In the 1990s, cave-diving equipment configurations became more standardized, due mostly to the adaptation and popularization of the "Hogarthian Rig", developed by several North Florida cave divers, named in honor of William "Hogarth" Main, which promotes equipment choices that "keep it simple and streamlined".

Today, the cave community is most focused on training, exploration, public awareness, and cave conservation.

Documentary films made by Wesley C. Skiles and Jill Heinerth have contributed to the increasing popularity of cave-diving in the early 21st century.

Australian history

Four divers using scuba dived from the Right Imperial Cave in the Jenolan system in the Blue Mountains to an upstream chamber on 30 October 1954.Cave-diving regions

Cave-diving venues can be found on all continents except Antarctica, where the average temperature is too low for water to remain liquid in caves. There are few flooded caves in Africa which are known and accessible. There are several in South Africa, a few in Namibia and Zimbabwe, and some large caves recently discovered in Madagascar. There are a large number of flooded caves in the limestone regions and other regions of Asia, particularly in the karst regions of China and Southeast Asia. Some are accessible for recreational cave-diving, but most have probably not yet been found or explored. Australia has many spectacular water filled caves and sinkholes, many of them in the Mount Gambier region of South Australia. Europe has a large number of flooded caves, particularly in the karst regions. North America has many cave-diving venues, particularly in Florida, USA, and the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. South America has some cave-diving venues in Brazil.Terminology

Caves and caverns as geographical entities are defined differently from cave-diving and cavern-diving, so it is possible to be cavern diving in what is technically a cave, and cave-diving in what is technically a cavern.Types of cave dive

A cave dive can be categorised by the topology of the route, which can be linear, include a circuit, or be a traverse.Caves by flow type

These terms describe flooded cave areas with reference to flow direction.Types of cave by method of formation

Types of cave by topology

*simple, linear, umbranched *simply branched *network, complex branched, anastomosed.See also

Notable cave divers: * * * * * * * * * * * * * Edd Sorenson - Florida cave diver, IUCRR member and Cave Adventurers owner Other: *References

Sources

*"Skin Diver Killed in Submerged Cave", '' The New York Times'', 16 May 1955, Page 47. *''Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival'',Sheck Exley

Sheck Exley (April 1, 1949 – April 6, 1994) was an American cave diver. He is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of cave diving, and he wrote two major books on the subject: '' Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival'' and ''Caverns M ...

1977.

External links

Atlas of Caves Worldwide

caveatlas.com

Florida Cave & Cavern List

Cave Diving Group, UK, 28 March 2010

Woodville Karst Plain Project

non profit organization about North Florida's underwater cave systems

Todd Kincaid, University of Wyoming

Global Underwater Explorers

non profit organization in Florida, education and exploration; Project Baseline, online spatial database of global underwater conditions

International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery (IUCRR)

International non profit organization registered in Florida

Cave Diving Down Under (Australia)

social media site for cave diving in Australia

Dominican Republic Speleological Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cave Diving