Catholic peace traditions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Catholic peace traditions begin with its biblical and classical origins and continue on to the current practice in the twenty-first century. Because of its long history and breadth of geographical and cultural diversity, this Catholic tradition encompasses many strains and influences of both religious and secular

Catholic peace traditions begin with its biblical and classical origins and continue on to the current practice in the twenty-first century. Because of its long history and breadth of geographical and cultural diversity, this Catholic tradition encompasses many strains and influences of both religious and secular

/ref> Peacemaking is an integral part of

The history of peacemaking in the Catholic tradition reflects the religious meanings of peace, tied to positive virtues, such as love, and to the personal and social works of justice. The Greek word for peace is ''eirene''; Roman ''pax'', and in the

The history of peacemaking in the Catholic tradition reflects the religious meanings of peace, tied to positive virtues, such as love, and to the personal and social works of justice. The Greek word for peace is ''eirene''; Roman ''pax'', and in the

peacemaking

Peacemaking is practical conflict transformation focused upon establishing equitable power relationships robust enough to forestall future conflict, often including the establishment of means of agreeing on ethical decisions within a community, ...

and many aspects of Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the theological and ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. Chr ...

, just war

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war i ...

and nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

.

Catholic tradition as a whole supports and favours peacemaking efforts.Kemmetmueller, Donna Jean. "Peace: The Challenge of Living the Catholic Tradition", ''Peace and Conflict Monitor''. May 9, 2005/ref> Peacemaking is an integral part of

Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching, commonly abbreviated CST, is an area of Catholic doctrine concerning matters of human dignity and the common good in society. The ideas address oppression, the role of the state (polity), state, subsidiarity, social o ...

.

Definitions

The history of peacemaking in the Catholic tradition reflects the religious meanings of peace, tied to positive virtues, such as love, and to the personal and social works of justice. The Greek word for peace is ''eirene''; Roman ''pax'', and in the

The history of peacemaking in the Catholic tradition reflects the religious meanings of peace, tied to positive virtues, such as love, and to the personal and social works of justice. The Greek word for peace is ''eirene''; Roman ''pax'', and in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

, ''shalom''.

For the earliest Romans, "pax" meant to live in a state of agreement, where discord and war were absent. In his ''Meditations'', or ''To Himself'', the Roman Emperor ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

expresses peace as a state of unperturbed tranquility. The English word "peace" derives ultimately from its root, the Latin "pax".

Shalom ( he, שלום) is the word for peace in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

(''''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''

The Gospels present the birth of Jesus as ushering in a new age of peace. In Luke, Zechariah celebrates his son

The Gospels present the birth of Jesus as ushering in a new age of peace. In Luke, Zechariah celebrates his son

/ref> The account of the healing of the centurion's servant suggests to John Eppstein that Jesus did not view military service as sinful, since rather than reprove the soldier for his profession, Jesus praised him for his faith. Nor did

/ref> John the Baptist's advice to soldiers was, "Do not practice extortion, do not falsely accuse anyone, and be satisfied with your wages."

/ref> Clement of Alexandria wrote, ""If you enroll as one of God's people, heaven is your country and God your lawgiver. And what are his laws? You shall not kill, You shall love your neighbor as yourself. To him that strikes you on the one cheek, turn to him the other also." (Protrepticus 10) "Selected Quotations", ''War, Peace and Conscience in the Catholic Tradition''

/ref> The early Christians anticipated the eminent return of the Lord in glory, even to the extent that

St. Paul wrote, "Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God. ... This is why you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Pay to all their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, toll to whom toll is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due."

The early Christian church believed that Christians should not take up arms in any war, and so struggled attempting to balance the obligation to be a good citizen and the question of whether it was permissible to take up arms to defend one's country. There developed a gap between the reasoning of the moral theorists and the practice of the private citizen.

As early as second century, Christians began to participate in Roman military, police, and government in large numbers. Military service was one way available to make a living, and on the borders of the empire there was a need to defend against barbarian incursions. As the army came to take on duties more in the line of police work: traffic and customs control, firefighting, the apprehension of criminals and bandits, maintaining the peace, quelling street brawls, and performing the roles of engineering, clearance, and other works of building for which the Roman army was well known, this choice became less problematic. The numbers of soldiers that came to be counted among the later martyrs indicates that many Christians served in the military, despite their abhorrence of war.

From about the middle of the second century, officers in the Roman army were expected to participate in the Imperial Cult and sacrifice to the emperor. During the reign of Diocletian this obligation was extended to the lower ranks, as a test for those suspected of being Christian. Christians were therefore counseled not to enlist so as to avoid needless blood guilt and the risk of idolatry, but should nonetheless continue to pray for the civil authorities.

Among the better-known soldier saints are

St. Paul wrote, "Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God. ... This is why you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Pay to all their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, toll to whom toll is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due."

The early Christian church believed that Christians should not take up arms in any war, and so struggled attempting to balance the obligation to be a good citizen and the question of whether it was permissible to take up arms to defend one's country. There developed a gap between the reasoning of the moral theorists and the practice of the private citizen.

As early as second century, Christians began to participate in Roman military, police, and government in large numbers. Military service was one way available to make a living, and on the borders of the empire there was a need to defend against barbarian incursions. As the army came to take on duties more in the line of police work: traffic and customs control, firefighting, the apprehension of criminals and bandits, maintaining the peace, quelling street brawls, and performing the roles of engineering, clearance, and other works of building for which the Roman army was well known, this choice became less problematic. The numbers of soldiers that came to be counted among the later martyrs indicates that many Christians served in the military, despite their abhorrence of war.

From about the middle of the second century, officers in the Roman army were expected to participate in the Imperial Cult and sacrifice to the emperor. During the reign of Diocletian this obligation was extended to the lower ranks, as a test for those suspected of being Christian. Christians were therefore counseled not to enlist so as to avoid needless blood guilt and the risk of idolatry, but should nonetheless continue to pray for the civil authorities.

Among the better-known soldier saints are

Persecutions were sporadic and the third century, largely local. By and large the Roman government didn't pay much attention to Christianity.

Christians sought to live the injunction to love their enemies while resisting their evil, even if this involved persecution and death: these were the

Persecutions were sporadic and the third century, largely local. By and large the Roman government didn't pay much attention to Christianity.

Christians sought to live the injunction to love their enemies while resisting their evil, even if this involved persecution and death: these were the

The sufferings of the martyrs were therefore not an act of suicide or some masochistic form of passive weakness that found its fulfillment in torture and death at the hands of the Romans. Theirs was an act of commitment carried out in the public arena, designed to show the enemy that what is worth living for is also worth dying for. According to Josephine Laffin, martyrdom demonstrated to all that Christ had overcome death, and that the Holy Spirit sustained the Church in its fight against darkness and evil.Laffin, Josephine. ''What Does it Mean to be a Saint?: Reflections on Mary MacKillop, Saints and Holiness in the Catholic Tradition'', p. 85, Wakefield Press, 2010

The

The

With the triumph of

With the triumph of

/ref> "He who does not ward off injury from his comrade, when he is able to, is just as guilty as he who does the injury."Egan, Eileen. ''Peace Be with You: Justified Warfare or the Way of Nonviolence'', Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004

When the Empress Justina sought to have the new basilica in Milan turned over to the Arians, Ambrose, supported by the faithful, occupied it himself in what Egan identifies as an example of non-violent resistance.

It is no coincidence that the appearance of the first monks comes within a few years of Constantine's assumption of power and the alliance of church and empire that he forged.

It is no coincidence that the appearance of the first monks comes within a few years of Constantine's assumption of power and the alliance of church and empire that he forged.

Christian monasticism started in Egypt, then spread to Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, and finally to Italy and southern Gaul.

/ref> Penances lasting from forty days to a year for killing someone in battle, were not uncommon. Following Augustine, war was seen as inherently sinful, and at best the lesser of two evils.Allman, Mark. ''Who Would Jesus Kill?: War, Peace, and the Christian Tradition'', "The Middle Ages", Saint Mary's Press, 2008

The Carolingian period saw the emergence of both a renewed Roman Empire of the West and the beginning of fresh barbarian invasions from the north and east and the rise of Islam. Internal efforts to legislate the life of the Christian Republic were therefore matched by its external defense against invasions by the

The Carolingian period saw the emergence of both a renewed Roman Empire of the West and the beginning of fresh barbarian invasions from the north and east and the rise of Islam. Internal efforts to legislate the life of the Christian Republic were therefore matched by its external defense against invasions by the

The laws provided sanctions against the killing of children, clerics, clerical students and peasants on clerical lands; against rape, against impugning the chastity of a noblewoman, and prohibited women from having to take part in warfare. Various factors, including Marian devotion in seventh- and eighth-century Ireland, may have contributed to inspire Adomnán to introduce these laws. Many of these things were already crimes, under the Irish

/ref> "Stewards of the Law" collected the fine and paid it to the victim or next of kin. Adomnán's initiative appears to be one of the first systematic attempts to lessen the savagery of warfare among Christians. In it he gave local expression, in the context of the Gaelic legal tradition, to a wider Christian movement to restrain violence. It was an early example of international law in that it was to be enforced in Ireland and northern Scotland, for it was the kings of those regions who were in attendance and signed as guarantors of the Law.

/ref> The ''Peace of God'' or ''Pax Dei'' was a proclamation issued by local clergy that decreed immunity from armed violence to noncombatants who could not defend themselves, beginning with the peasants (''agricolae'') and the clergy. It included the clergy and their possessions; the poor; women; peasants along with their tools, animals, mills, vineyards, and labor; and later pilgrims and merchants: in short, the vast majority of the medieval population who neither bore arms, nor were entitled to bear them. Children and women were added to the early protections. Merchants and their goods were added to the protected groups in a synod of 1033. The ''Pax Dei'' prohibited nobles from invading churches, beating the defenseless, and burning houses.

/ref> It dates from the eleventh century. While the Truce of God was a temporary suspension of hostilities, as distinct from the Peace of God which was permanent, the jurisdiction of the Truce of God was broader. The Peace of God prohibited fighting on Sundays, and ferial days (feast days on which people were not obliged to work). It was the sanctification of Sunday which gave rise to the Truce of God, for it had always been agreed not to do battle on that day and to suspend disputes in the law-courts. It confirmed permanent peace for all churches and their grounds, the monks, clerks and chattels; all women, pilgrims, merchants and their servants, cattle and horses; and men at work in the fields. For all others peace was required throughout Advent, the season of Lent, and from the beginning of the Rogation days until eight days after Pentecost. This prohibition was subsequently extended to specific days of the week, viz., Thursday, in memory of the Ascension, Friday, the day of the Passion, and Saturday, the day of the Resurrection (council 1041). By the middle of the twelfth century the number of proscribed days was extended until there was left some eighty days for fighting. The Truce soon spread from France to Italy and Germany; the oecumenical council of 1179 extended the institution to the whole Church by Canon xxi, "De treugis servandis", which was inserted in the collection of canon law, Decretal of Gregory IX, I, tit., "De treuga et pace".

/ref> Aquinas challenged the Truce, holding that it was lawful to wage war to safeguard the commonweal on holy days and feast days.

/ref>

Vitoria adopted from Aquinas the Roman law concept of ''ius gentium'' ("the law of nations"). His defense of American Indians was based on a Scholastic understanding of the intrinsic dignity of man, a dignity he found being violated by Spain's policies in the New World. Dominican friar

German Resistance Memorial Centre, Index of Persons; retrieved at 4 September 2013 Belgian Cardinal

/ref> John's successors

/ref>

/ref> In the late 1970s Hurley held a daily silent protest, standing in front of the central Durban Post Office for a period each day with a placard expressing his opposition to apartheid and the displacement of people from their homes.

/ref> He received many death threats and was at times subject to house arrest. According to Gerald Shaw writing for ''The Guardian'', "It was in part due to his sustained moral crusade and that of other churchmen that the transition to democracy, when it came in 1994, was accepted by white people in peace and good order." Hurley is remembered for his contribution to the struggle against apartheid, his concern for the poor and his commitment towards a more just and peaceful society.

/ref> Beyond its effects on the Philippines, the peaceful ouster of Marcos has been cited as a milestone in the movement toward popularly chosen governments throughout the world.

/ref>

After the war Catholic peacemaking narrowed down to a very few institutions, including the

After the war Catholic peacemaking narrowed down to a very few institutions, including the

/ref> According to Garret Mattingly,

/ref> *On June 8, 2014 Pope Francis welcoming the Israeli and Palestinian presidents to the Vatican for an evening of peace prayers just weeks after the last round of U.S.-sponsored negotiations collapsed.

Merton, Thomas. ''The Nonviolent Alternative''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980

* * Musto, Ronald G

''Liberation Theologies: A Research Guide''

New York: Garland, 1991. * * O'Brien, David J. and Thomas A. Shannon, eds

''Renewing the Earth: Catholic Documents on Peace, Justice and Liberation''

Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977 * Pagden, Anthony. ''Vitoria: Political Writings'', Cambridge University Press, 1991 * * Zahn, Gordon

''War, Conscience and Dissent''

New York: Hawthorne, 1967.

Mattingly, Garrett. ''Renaissance Diplomacy'', 1955

{{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Peace Traditions Catholic theology and doctrine Religion and peace Christian pacifism

''

''Eirene''

The Greek meaning for peace, contained in the word ''eirene'', evolved over the course of Greco-Roman civilization from such agricultural meanings as prosperity, fertility, and security of home contained inHesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

's ''Works and Days'', to more internal meanings of peace formulated by the Stoics, such as Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

.

''Eirene'' is the word that the New Testament generally uses for peace, one of the twenty words used by the Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond th ...

, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible used in the largely Greek-speaking Jewish communities throughout the Greco-Roman world. It is chiefly through the Septuagint's use of Greek that the Greek word ''eirene'' became infused with all the religious imagery and richness of the word ''shalom'' in the Hebrew Bible that had evolved over the history of the Jewish people. Subsequently, the use of the Greek Bible as the basis for St. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is com ...

's Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

translation into Latin then brought all the new meanings of ''eirene'' to the Latin word ''pax'' and transformed it from a term for an imposed order of the sword, the ''Pax Romana'', into the chief image of peace for Western Christianity.Musto, Ronald G., ''The Catholic Peace Tradition'', Orbis Books, 1986New Testament

The Gospels present the birth of Jesus as ushering in a new age of peace. In Luke, Zechariah celebrates his son

The Gospels present the birth of Jesus as ushering in a new age of peace. In Luke, Zechariah celebrates his son John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

:

And you, child, will be called prophet of the Most High, for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give his people knowledge of salvation through the forgiveness of their sins, because of the tender mercy of our God by which the daybreak from on high will visit us to shine on those who sit in darkness and death's shadow, to guide our feet into the path of peace.And later, the angels appear to the shepherds at Bethlehem, "And suddenly there was a multitude of the heavenly host with the angel, praising God and saying: 'Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests'" – a peace distinct from the

Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is periodization, identified as a period and as a golden age (metaphor), golden age of increased as well as sustained Imperial cult of ancient Rome ...

.

The Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount (anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is ...

(Mt. 5:1-16) and the Sermon on the Plain

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

(Lk. 6:20-45) combine with the call to "love your enemies" (Mt. 5:38-48) to encapsulate Jesus' teachings on peacemaking. According to Gabriel Moran

Gabriel Moran, AFSC (11 August 1935 – 15 October 2021) was an American scholar and teacher in the fields of Christian theology and religious education. His writings made significant contributions to the development of Catholic Church, Catholic t ...

, the Sermon on the Mount does not advocate submission to oppressors, but rather a strategy to "de-hostilize enemies in order to win them over".Moran, Gabriel. "Roman Catholic Tradition and Passive Resistance", New York University/ref> The account of the healing of the centurion's servant suggests to John Eppstein that Jesus did not view military service as sinful, since rather than reprove the soldier for his profession, Jesus praised him for his faith. Nor did

Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

require Cornelius to resign his commission or desert upon being baptized.Eppstein, John. ''The Catholic Tradition of the Law of Nations'', Burns & Oates, London, 1935/ref> John the Baptist's advice to soldiers was, "Do not practice extortion, do not falsely accuse anyone, and be satisfied with your wages."

Early Church

Early Christianity was relatively pacifist.McCormick, Patrick. "Catholic Social Teaching & the Catholic Intellectual Tradition", The Catholic University/ref> Clement of Alexandria wrote, ""If you enroll as one of God's people, heaven is your country and God your lawgiver. And what are his laws? You shall not kill, You shall love your neighbor as yourself. To him that strikes you on the one cheek, turn to him the other also." (Protrepticus 10) "Selected Quotations", ''War, Peace and Conscience in the Catholic Tradition''

/ref> The early Christians anticipated the eminent return of the Lord in glory, even to the extent that

Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

had to tell some of them to get back to work. Generally they were not deeply involved in the larger community. As it became apparent that a more nuanced understanding was called for, Christians came to realize that if they were to survive socially they could not remain within the confines of their own community.Massaro, S.J. and Shannon, Thomas A., ''Catholic Perspectives on Peace and War'', Sheed & Ward, 2003Christians in the Roman Army

St. Paul wrote, "Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God. ... This is why you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Pay to all their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, toll to whom toll is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due."

The early Christian church believed that Christians should not take up arms in any war, and so struggled attempting to balance the obligation to be a good citizen and the question of whether it was permissible to take up arms to defend one's country. There developed a gap between the reasoning of the moral theorists and the practice of the private citizen.

As early as second century, Christians began to participate in Roman military, police, and government in large numbers. Military service was one way available to make a living, and on the borders of the empire there was a need to defend against barbarian incursions. As the army came to take on duties more in the line of police work: traffic and customs control, firefighting, the apprehension of criminals and bandits, maintaining the peace, quelling street brawls, and performing the roles of engineering, clearance, and other works of building for which the Roman army was well known, this choice became less problematic. The numbers of soldiers that came to be counted among the later martyrs indicates that many Christians served in the military, despite their abhorrence of war.

From about the middle of the second century, officers in the Roman army were expected to participate in the Imperial Cult and sacrifice to the emperor. During the reign of Diocletian this obligation was extended to the lower ranks, as a test for those suspected of being Christian. Christians were therefore counseled not to enlist so as to avoid needless blood guilt and the risk of idolatry, but should nonetheless continue to pray for the civil authorities.

Among the better-known soldier saints are

St. Paul wrote, "Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God. ... This is why you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Pay to all their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, toll to whom toll is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due."

The early Christian church believed that Christians should not take up arms in any war, and so struggled attempting to balance the obligation to be a good citizen and the question of whether it was permissible to take up arms to defend one's country. There developed a gap between the reasoning of the moral theorists and the practice of the private citizen.

As early as second century, Christians began to participate in Roman military, police, and government in large numbers. Military service was one way available to make a living, and on the borders of the empire there was a need to defend against barbarian incursions. As the army came to take on duties more in the line of police work: traffic and customs control, firefighting, the apprehension of criminals and bandits, maintaining the peace, quelling street brawls, and performing the roles of engineering, clearance, and other works of building for which the Roman army was well known, this choice became less problematic. The numbers of soldiers that came to be counted among the later martyrs indicates that many Christians served in the military, despite their abhorrence of war.

From about the middle of the second century, officers in the Roman army were expected to participate in the Imperial Cult and sacrifice to the emperor. During the reign of Diocletian this obligation was extended to the lower ranks, as a test for those suspected of being Christian. Christians were therefore counseled not to enlist so as to avoid needless blood guilt and the risk of idolatry, but should nonetheless continue to pray for the civil authorities.

Among the better-known soldier saints are Saint Marinus

Saint Marinus (; it, San Marino) was an Early Christian and the founder of a chapel and monastery in 301 from whose initial community the state of San Marino later grew.

Life

Tradition holds that he was a stonemason by trade who came from the ...

, Marcellus of Tangier

Saint Marcellus of Tangier or Saint Marcellus the Centurion ( es, San Marcelo) (c. mid 3rd century – 298 AD) was a Roman centurion who is today venerated as a martyr-saint by the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. His feast day i ...

, and Maximilian of Tebessa

Saint Maximilian of Tebessa, also known as Maximilian of Numidia, ( la, Maximilianus; AD 274–295) was a Christian saint and martyr, whose feast day is observed on 12 March. Born in AD 274, the son of Fabius Victor, an official connected to the R ...

, and Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

.

Martyrdom as non-violent protest

Persecutions were sporadic and the third century, largely local. By and large the Roman government didn't pay much attention to Christianity.

Christians sought to live the injunction to love their enemies while resisting their evil, even if this involved persecution and death: these were the

Persecutions were sporadic and the third century, largely local. By and large the Roman government didn't pay much attention to Christianity.

Christians sought to live the injunction to love their enemies while resisting their evil, even if this involved persecution and death: these were the martyrs

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

. The word ''martyr'' is the Greek for "witness". The early martyrs followed a long-standing tradition; John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

was beheaded for "speaking truth to power". They also had as examples St. Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, the apostles James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, and Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Ch ...

, and others.Philpott, Daniel. "The Early Church", Notre Dame UniversityThe sufferings of the martyrs were therefore not an act of suicide or some masochistic form of passive weakness that found its fulfillment in torture and death at the hands of the Romans. Theirs was an act of commitment carried out in the public arena, designed to show the enemy that what is worth living for is also worth dying for. According to Josephine Laffin, martyrdom demonstrated to all that Christ had overcome death, and that the Holy Spirit sustained the Church in its fight against darkness and evil.Laffin, Josephine. ''What Does it Mean to be a Saint?: Reflections on Mary MacKillop, Saints and Holiness in the Catholic Tradition'', p. 85, Wakefield Press, 2010

Martyrs of Cordoba

The

The Martyrs of Córdoba

The Martyrs of Córdoba were forty-eight Christian martyrs who were executed under the rule of Muslim administration in Al-Andalus (name of the Iberian Peninsula under the Islamic rule). The hagiographical treatise written by the Iberian Christ ...

were forty-eight Christian martyrs living in the ninth-century Muslim-ruled Al-Andalus. Their hagiography describes in detail their executions for deliberately sought capital violations of Muslim law in Al-Andalus. The martyrdoms recorded by Eulogius took place between 851 and 859; with few exceptions, the Christians invited execution by making public statements tactically chosen to invite martyrdom by appearing before the Muslim authorities to denounce Islam. The martyrs caused tension not only between Muslims and Christians, but within the Christian community. In December 852 Church leaders called a council in Cordoba, which honored those fallen but called on Christians to refrain from seeking martyrdom.

Recent historical interpretation of the martyr movement reflect questions on its nature. Kenneth Baxter Wolf

Kenneth Baxter Wolf (born June 1, 1957) is an American historian and scholar of medieval studies.

Biography

Wolf is the John Sutton Miner Professor of History and Professor of Classics at Pomona College in Claremont, California, where he has ...

sees its cause in "spiritual anxiety" and the penitential aspect of ninth-century Iberian Christianity. Clayton J. Drees sees their motives in a "pathological death-wish, the product of unexpressed hatred toward society that had turned inward against themselves" and other innate "psychological imbalances". Jessica A. Coope suggests that it reflects a protest against the process of assimilation, and that the martyrs demonstrated a determination to assert Christian identity.Coope, Jessica A., ''The Martyrs of Córdoba: Community and Family Conflict in an Age of Mass Conversion'', p. 14, University of Nebraska Press, 1995Age of Constantine

With the triumph of

With the triumph of Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

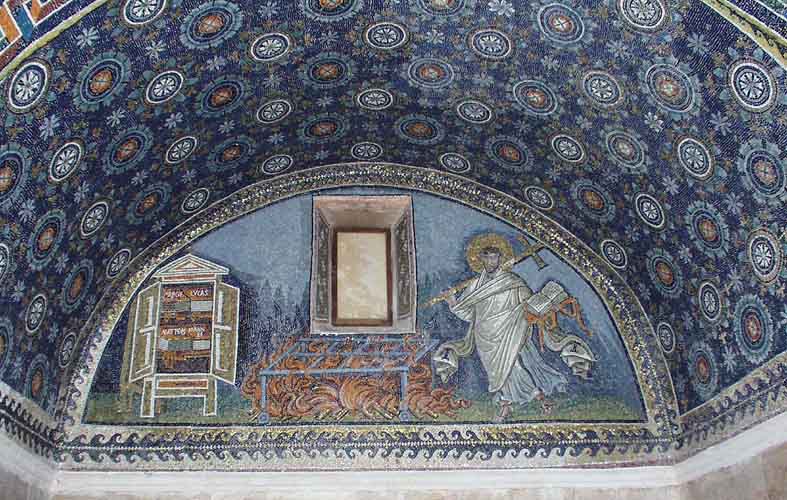

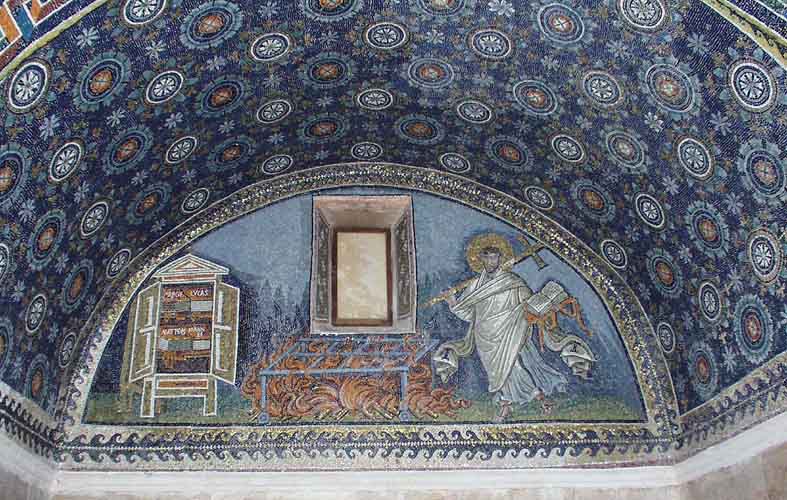

as sole Roman emperor in 313, the church of the martyrs now found itself an accepted and favored religion, soon to become the official religion of the state. Constantine had an emblem inscribed on the shields of his soldiers that has been various described as representing the "Unconquerable Sun" or as a Chi-Rho

The Chi Rho (☧, English pronunciation ; also known as ''chrismon'') is one of the earliest forms of Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi (letter), chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word (Christ (title), ...

. Eileen Egan

Eileen Egan (1912–2000) was a journalist, Roman Catholic activist, and co-founder of the Catholic peace group, American PAX Association and its successor Pax Christi-USA, the American branch of International Pax Christi. Starting 1943 she remaine ...

quotes Burkhardt's observation that this was "an emblem which every man could interpret as he pleased, but which the Christians would refer to themselves."

As the religion of the empire, its survival was tied to the fate of the Empire. The threat of increased barbarian incursions therefore threatened both, and defense of the Empire was appropriate in order to protect Christianity. The early trend toward pacifism became muted.

Ambrose of Milan

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promot ...

, former Pretorian Prefect of northern Italy before being elected bishop of Milan, preserved the Christian presumption against the use of violence, unless it was needed to protect important social values. While rejecting resorting to violence in self-defense, he argued that charity demanded one protect one's neighbour.Duncan C.Ss.R., Bruce. "The Struggle to Develop a Just War Tradition in the West", Australian Catholic Social Justice Council, April 8, 2003/ref> "He who does not ward off injury from his comrade, when he is able to, is just as guilty as he who does the injury."Egan, Eileen. ''Peace Be with You: Justified Warfare or the Way of Nonviolence'', Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004

When the Empress Justina sought to have the new basilica in Milan turned over to the Arians, Ambrose, supported by the faithful, occupied it himself in what Egan identifies as an example of non-violent resistance.

Augustine of Hippo

Following Ambrose,Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

thought that the Christian, in imitation of Jesus, should not use violence to defend himself, but however, had an obligation to aid a victim under attack.

Augustine of Hippo agreed strongly with the conventional wisdom of his time, that Christians should be pacifists philosophically, but that they should use defense as a means of preserving peace in the long run. He routinely argued that pacifism did not prevent the defence of innocents. In essence, the pursuit of peace might require fighting to preserve it in the long-term. Such a war must not be preemptive, but defensive, to restore peace.

Augustine drew on Roman tradition to view a "just war" as one prosecuted under lawful authority for a just cause, i.e., repelling aggression or injury, retaking something wrongly seized, or to punish wrongdoing. Later other theorists expanded on this. War must be the last resort, have a reasonable chance of success, and produce more good than harm. The church also argued that non-combatants must be protected.

Augustine drew no distinction between offensive and defensive wars, since remedying injuries was a just cause apart from defence. Against the threat of chaos and breakdown of civil order, a man may wage war justly but lament his unavoidable duty.

Barbarian Invasions

During Augustine's last days Vandals invaded North Africa. Barbarian incursions which later swept Europe in succeeding centuries resulted in a collapse of learning and culture, and population decline. There is a long historical tradition that has collected ample evidence to show that the Roman Empire itself was undergoing profound social, economic, and spiritual changes that were only hastened by the invasions. As the Western Empire crumbled the Church became the stabilizing force for order and peace. The Christian peacemakers of this period were not the dominant cultural or political force of their time, but were either marginalized minorities — as in the case of the Roman Empire or — as in the case of the missionaries who evangelized the barbarians — were actually reaching out from an oppressive and collapsing world to an anarchic one that offered the seeds of a new society. Among the more important figures of active peacemaking or of intellectual life worth further study wereMartin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

, Salvian of Marseilles

Salvian (or Salvianus) was a Christian writer of the 5th century in Roman Gaul.

Personal life

Salvian's birthplace is uncertain, but some scholars have suggested Cologne or Trier some time between 400 and 405. He was educated at the school of Tri ...

, Nicetas of Remesiana

Nicetas (c. 335–414) was Bishop of Remesiana (present-day Bela Palanka, Serbia), which was then in the Roman province of Dacia Mediterranea.

Biography

Nicetas promoted Latin sacred music for use during the Eucharistic worship and reputedly co ...

, Germanus of Auxerre

Germanus of Auxerre ( la, Germanus Antissiodorensis; cy, Garmon Sant; french: Saint Germain l'Auxerrois; 378 – c. 442–448 AD) was a western Roman clergyman who was bishop of Autissiodorum in Late Antique Gaul. He abandoned a career as a h ...

, Severinus of Noricum

Severinus of Noricum ( 410 – 8 January 482) is a saint, known as the "Apostle to Noricum". It has been speculated that he was born in either Southern Italy or in the Roman province of Africa. Severinus himself refused to discuss his personal ...

, St. Patrick

ST, St, or St. may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Stanza, in poetry

* Suicidal Tendencies, an American heavy metal/hardcore punk band

* Star Trek, a science-fiction media franchise

* Summa Theologica, a compendium of Catholic philosophy an ...

, St. Genevieve

Genevieve (french: link=no, Sainte Geneviève; la, Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; 419/422 AD –

502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Her feast is on 3 January.

Genevieve was born in Nanterre an ...

of Paris, Columban

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

, and St. Boniface of Crediton.

Monasticism

It is no coincidence that the appearance of the first monks comes within a few years of Constantine's assumption of power and the alliance of church and empire that he forged.

It is no coincidence that the appearance of the first monks comes within a few years of Constantine's assumption of power and the alliance of church and empire that he forged. Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and giv ...

identified one of the reasons individuals sought out the desert was that they "declined to be ruled by men, but had no desire to rule over others themselves'. Others sought to imitate Jesus' own time spent in the desert.

Monasticism was, in a sense, a continuation of martyrdom, reaffirming the contradiction between the Church and the world, by fleeing from the corruption of civilization in order to seek a greater treasure.Hitchcock, James. ''History of the Catholic Church: From the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium'', Ignatius Press, 2012Christian monasticism started in Egypt, then spread to Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, and finally to Italy and southern Gaul.

Anthony the Hermit

Anthony the Hermit (ca. 468 – ca. 520), also known as Anthony of Lérins, is a Christian who is venerated as a saint. He was born in the ancient Roman province of Valeria (now Hungary), then part of the Hunnic Empire. When he was eight years o ...

( 251-356), the founder of monasticism, and Pachomius

Pachomius (; el, Παχώμιος ''Pakhomios''; ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Copts, Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on ...

(c. 290-346) were the prototypes.

Penitentials

The penitentials, written by Irish monks, were a series of manuals designed for priests who heard confessions that specified certain penances for certain categories of sins. These "penitentials" borrowed inspiration and specific regulations from the early church councils, monastic rules, and the letters of popes and bishops. Many of the regulations at first paralleled those aimed at insuring the special status of the clergy, including its nonviolence, but were gradually extended to the lay population. Penances ranged from fasting on bread and water for week, paying compensation to victims in money, goods or property, exile, pilgrimage, and excommunication. Readmission to Christian community was possible only after the completion of the prescribed penance. These manuals proved to be such a concise and effective method for conceptualizing and standardizing notions of sin and repentance that they spread from Ireland to the Continent in a wide variety of collections that became enshrined in official collections of church law by the twelfth century. The penitentials are of great value for studying early medieval notions of violence, its seriousness and its consequences in a variety of actions, circumstances, and classes of victims. The texts assign penances for killing in wartime, even under the lawful command of legitimate authority.Winwright, Tobias. "Make Us Channels of Your Peace", ''Gathered for the Journey: Moral Theology in Catholic Perspective'', David Matzko McCarthy, and M. Therese Lysaught eds., Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, 9780802825957/ref> Penances lasting from forty days to a year for killing someone in battle, were not uncommon. Following Augustine, war was seen as inherently sinful, and at best the lesser of two evils.Allman, Mark. ''Who Would Jesus Kill?: War, Peace, and the Christian Tradition'', "The Middle Ages", Saint Mary's Press, 2008

The Middle Ages

The Carolingian period saw the emergence of both a renewed Roman Empire of the West and the beginning of fresh barbarian invasions from the north and east and the rise of Islam. Internal efforts to legislate the life of the Christian Republic were therefore matched by its external defense against invasions by the

The Carolingian period saw the emergence of both a renewed Roman Empire of the West and the beginning of fresh barbarian invasions from the north and east and the rise of Islam. Internal efforts to legislate the life of the Christian Republic were therefore matched by its external defense against invasions by the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic ...

, and Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century Germany in the Middle Ages, German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings, to refer ...

. The problems and conditions were in many ways similar to those of Christian thinkers under the late Roman Empire when the state was identified with Christian society. The Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lom ...

thus brought a renewed militarization of society that sought to protect Christendom from external threat, while it used the hierarchical bonds of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

oaths and vassalage

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. W ...

to bring the new class of mobile horse warriors, the ''milities'', to some semblance of central authority. War took on a religious dimension as evidenced by liturgical formulae for the blessings of armies and weapons.

The close identification of the Carolingian Empire with the extent of Western Christianity revived the late Roman associations of ''Christianitas'' (Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

) with the ''orbis Romanus'' or ''oikoumene'' (the Roman world). On the most official levels Christian peace necessitated its defense against the attacks of external enemies.

Christian peace involved the monastic or ascetic peace of a pure heart and life devoted to prayer; the episcopal peace, or pax ecclesiae, of a properly functioning free and unified church; and the social or imperial peace of the world. These often overlapped.

Carolingian theory established two, separate, ecclesiastical and secular spheres of authority within Christian society, one to lead the body and one the spirit. Monastic life was supported, and encouraged; while late Roman prohibitions against clerical participation in the army were repeated again and again. Among the thinkers and writers on issues of peace and peacemaking were Alcuin of York

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

, Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel

Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel< OSB ( 770 – c. 840) was a monk of Paschasius Radbertus

Paschasius Radbertus (785–865) was a Carolingian theologian and the abbot of Corbie, a monastery in Picardy founded in 657 or 660 by the queen regent Bathilde with a founding community of monks from Luxeuil Abbey. His most well-known and influe ...

, and Hincmar of Rheims. In keeping with their time, these offered various interpretations of peace as an inner tranquillity, legal guidelines to war and the curbing of military violence, or the image of peace as an ideal Christian state.

The Cain Adomnan

The ''Cáin Adomnáin'' (Law of Adomnán), also known as the ''Lex Innocentium'' (Law of Innocents) was promulgated amongst a gathering ofIrish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

, Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is now ...

n and Pictish

Pictish is the extinct language, extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited num ...

notables at the Synod of Birr in 697

__NOTOC__

Year 697 ( DCXCVII) was a common year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. The denomination 697 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar e ...

. It is named after its initiator Adomnán of Iona

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (, la, Adamnanus, Adomnanus; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and saint. He was the author of the ''Life of Col ...

, ninth Abbot of Iona after St. Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

. As a successor of Columba of Iona, Adomnán had sufficient prestige to assemble a conference of ninety-one chieftains and clerics from Ireland, Dál Riata, and Pictland at Birr to promulgate the new law. As well as being the site of a significant monastery, associated with Saint Brendan of Birr

Saint Brendan of Birr (died c. 572) was one of the early Irish monastic saints. He was a monk and later an abbot, of the 6th century. He is known as "St Brendan the Elder" to distinguish him from his contemporary and friend St Brendan the Navig ...

, Birr was close to the boundary between the Uí Néill-dominated northern half of Ireland, and the southern half, where the kings of Munster ruled. It therefore represented a neutral ground where the rival kings and clerics of north and south Ireland could meet.

This set of laws were designed, among other things, to guarantee the safety and immunity of various types of non-combatants in warfare."Law of the Innocents", Foghlam AlbaThe laws provided sanctions against the killing of children, clerics, clerical students and peasants on clerical lands; against rape, against impugning the chastity of a noblewoman, and prohibited women from having to take part in warfare. Various factors, including Marian devotion in seventh- and eighth-century Ireland, may have contributed to inspire Adomnán to introduce these laws. Many of these things were already crimes, under the Irish

Brehon Laws

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of Freemen), also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norma ...

. The law described both the secular fines which criminals must pay, and the ritual curses to which law-breakers were subject.

The indigenous Brehon Laws

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of Freemen), also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norma ...

were committed to parchment about the seventh century, most likely by clerics. Most scholars now believe that the secular laws were not compiled independently of monasteries. Adomnan would have had access to the best legal minds of his generation. Adomnan's ''Cain'' combined aspects of the traditional Brehon laws with an ecclesiastical approach. Following Ambrose and Augustine, bystanders who did nothing to prevent a crime were as liable as the perpetrator.Grigg, Julianna. "Aspects of the Cain: Adomnan's Lex Innocentium", ''Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association'', Vol.1, 2005/ref> "Stewards of the Law" collected the fine and paid it to the victim or next of kin. Adomnán's initiative appears to be one of the first systematic attempts to lessen the savagery of warfare among Christians. In it he gave local expression, in the context of the Gaelic legal tradition, to a wider Christian movement to restrain violence. It was an early example of international law in that it was to be enforced in Ireland and northern Scotland, for it was the kings of those regions who were in attendance and signed as guarantors of the Law.

Peace of God

As Carolingian authority began to erode, especially on the outskirts of power, as in southernGaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, the episcopate took steps to protect their congregations and their holdings against the encroachments of local nobles. The Peace of God originated in the conciliar assemblies of the late Carolingian period. It began in Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

, Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

and Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

, areas where central authority had most completely fragmented.

A limited ''Pax Dei'' was decreed at the Synod of Charroux in 989 and spread to most of Western Europe over the next century, surviving in some form until at least the thirteenth century.

A great crowd of many people (''populus'') gathered from the Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

, the Limousin

Limousin (; oc, Lemosin ) is a former administrative region of southwest-central France. On 1 January 2016, it became part of the new administrative region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. It comprised three departments: Corrèze, Creuse, and Haute-Vienn ...

, and neighboring regions. Relics of saints were displayed and venerated. The participation of large, enthusiastic crowds marks it as one of the first popular religious movements of the Middle Ages. In the early phase, the blend of relics and crowds, and enthusiasm stamped the movement with an exceptionally popular character.Landes, Richard. "Peace of God: ''Pax Dei''/ref> The ''Peace of God'' or ''Pax Dei'' was a proclamation issued by local clergy that decreed immunity from armed violence to noncombatants who could not defend themselves, beginning with the peasants (''agricolae'') and the clergy. It included the clergy and their possessions; the poor; women; peasants along with their tools, animals, mills, vineyards, and labor; and later pilgrims and merchants: in short, the vast majority of the medieval population who neither bore arms, nor were entitled to bear them. Children and women were added to the early protections. Merchants and their goods were added to the protected groups in a synod of 1033. The ''Pax Dei'' prohibited nobles from invading churches, beating the defenseless, and burning houses.

Excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

would be the punishment for attacking or robbing a church, for robbing peasants or the poor of farm animals and for robbing, striking or seizing a priest or any man of the clergy "who is not bearing arms". Making compensation or reparations could circumvent the anathema of the Church.

After a lull in the first two decades of the eleventh century, the movement spread to the north with the support of king Robert, the Capetian. There, the high nobility sponsored peace assemblies throughout Flanders, Burgundy, Champagne, Normandy, Amienois, and Berry. By 1041 the peace had spread throughout France and had reached Flanders and Italy. From c. 1018 the peace was extended to Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and reached Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, Girona

Girona (officially and in Catalan language, Catalan , Spanish: ''Gerona'' ) is a city in northern Catalonia, Spain, at the confluence of the Ter River, Ter, Onyar, Galligants, and Güell rivers. The city had an official population of 103,369 in ...

, and Urgel. Assemblies were repeated all over western Europe into the 1060s.

Truce of God

The Truce of God or ''Treuga Dei'' had its origin in Normandy in the city of Caen.Watkin, William Ward. "The Middle Ages: The Approach to the Truce of God", ''The Rice Institute Pamphlet'', Vol. XXIX, No. 4, October, 1942/ref> It dates from the eleventh century. While the Truce of God was a temporary suspension of hostilities, as distinct from the Peace of God which was permanent, the jurisdiction of the Truce of God was broader. The Peace of God prohibited fighting on Sundays, and ferial days (feast days on which people were not obliged to work). It was the sanctification of Sunday which gave rise to the Truce of God, for it had always been agreed not to do battle on that day and to suspend disputes in the law-courts. It confirmed permanent peace for all churches and their grounds, the monks, clerks and chattels; all women, pilgrims, merchants and their servants, cattle and horses; and men at work in the fields. For all others peace was required throughout Advent, the season of Lent, and from the beginning of the Rogation days until eight days after Pentecost. This prohibition was subsequently extended to specific days of the week, viz., Thursday, in memory of the Ascension, Friday, the day of the Passion, and Saturday, the day of the Resurrection (council 1041). By the middle of the twelfth century the number of proscribed days was extended until there was left some eighty days for fighting. The Truce soon spread from France to Italy and Germany; the oecumenical council of 1179 extended the institution to the whole Church by Canon xxi, "De treugis servandis", which was inserted in the collection of canon law, Decretal of Gregory IX, I, tit., "De treuga et pace".

/ref> Aquinas challenged the Truce, holding that it was lawful to wage war to safeguard the commonweal on holy days and feast days.

Thomas Aquinas

In his ''Summa Theologica'', Thomas Aquinas expands Augustine's arguments to define the conditions under which a war could be just: * War must occur for a good and just purpose rather than the pursuit of wealth or power. * Just war must be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state. * Peace must be a central motive even in the midst of violence.The Crusades

Religious thinkers and secular writers attempted to incorporate the controls of the Peace and Truce of God into the existing warrior ethic by "Christianizing" it into the Crusades and the cult ofchivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours we ...

. Beginning in the eleventh century, knighthood developed a religious character. Prospective knights underwent rigorous religious rituals in order to be initiated. An initiate had to fast, confess his sins, was given a symbolic bath, had his hair cut to represent humility, and he spent a night praying, his weapons upon an altar representing the dedication of his weapons to the Church and God. Advancements in metallurgy allowed inscriptions and pictures of holy symbols to be engraved on helmets, swords, shields, and other equipment. The symbols allowed for a physical reminder to knights and military men that God was supporting their efforts, providing protection to those soldiers as well as the assurance of a victory over their enemies.

Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

is equally famous for his failed crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

and for the settlement of disputes and the maintenance of peace within Christian lands. He issued the first extant ordinance indefinitely prohibiting warfare in France, a text dating from January 1258 that outlawed guerrae omnes as well as arson, and disturbances to carts and to agricolae who work with carts or plows. Those who transgressed this prohibition were to be punished as peace-breakers (fractores pacis) by the king's officer and the bishop-elect of le Puy-en-Velay. Louis IX promulgated this text as a simple royal act on the basis of his authority as king.Firnhaber-Baker, Justine. "From God's Peace to the King's Order: Late Medieval Limitations on Non-Royal Warfare", ''Essays in Medieval Studies'', Volume 23, 2006, pp. 19-30/ref>

Alternatives to the Crusades

Christian missionary work was presented as a viable alternative to the violence of the crusaders. Majorcan Franciscan BlessedRamon Llull

Ramon Llull (; c. 1232 – c. 1315/16) was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'', conceived as a type of universal logic to pro ...

(1232-1315) argued that the conversion of Muslims should be achieved through prayer, not through military force, and pressed for the study of Arabic to prepare potential missionaries. He traveled through Europe to meet with popes, kings, and princes, trying to establish special colleges to prepare them.

Renaissance and Reformation (c. 1400 – c. 1800)

Humanism

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

laid a foundation for religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

. In ''De libero arbitrio'', he noted that religious disputants should be temperate in their language, "because in this way the truth, which is often lost amidst too much wrangling may be more surely perceived." Gary Remer writes, "Like Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, Erasmus concludes that truth is furthered by a more harmonious relationship between interlocutors." Although Erasmus did not oppose the punishment of heretics, in individual cases he generally argued for moderation and against the death penalty. He wrote, "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."

Age of Exploration

Francisco de Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( – 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosophy, philosopher, theology, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known ...

was a Spanish Dominican philosopher, considered one of the founders of early international law. He was educated at the College Saint-Jacques in Paris, where he was influenced by the work of Desidarius Erasmus. In 1524, he held the Chair of theology at the University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca ( es, Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX. It is th ...

, where a number of missionaries returning from the New World expressed concern regarding treatment of the indigenous inhabitants. In three lectures held between 1537 and 1539 Vitoria concluded that the Indians were rightful owners of their property and that their chiefs validly exercised jurisdiction over their tribes. A supporter of the just war theory

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war is m ...

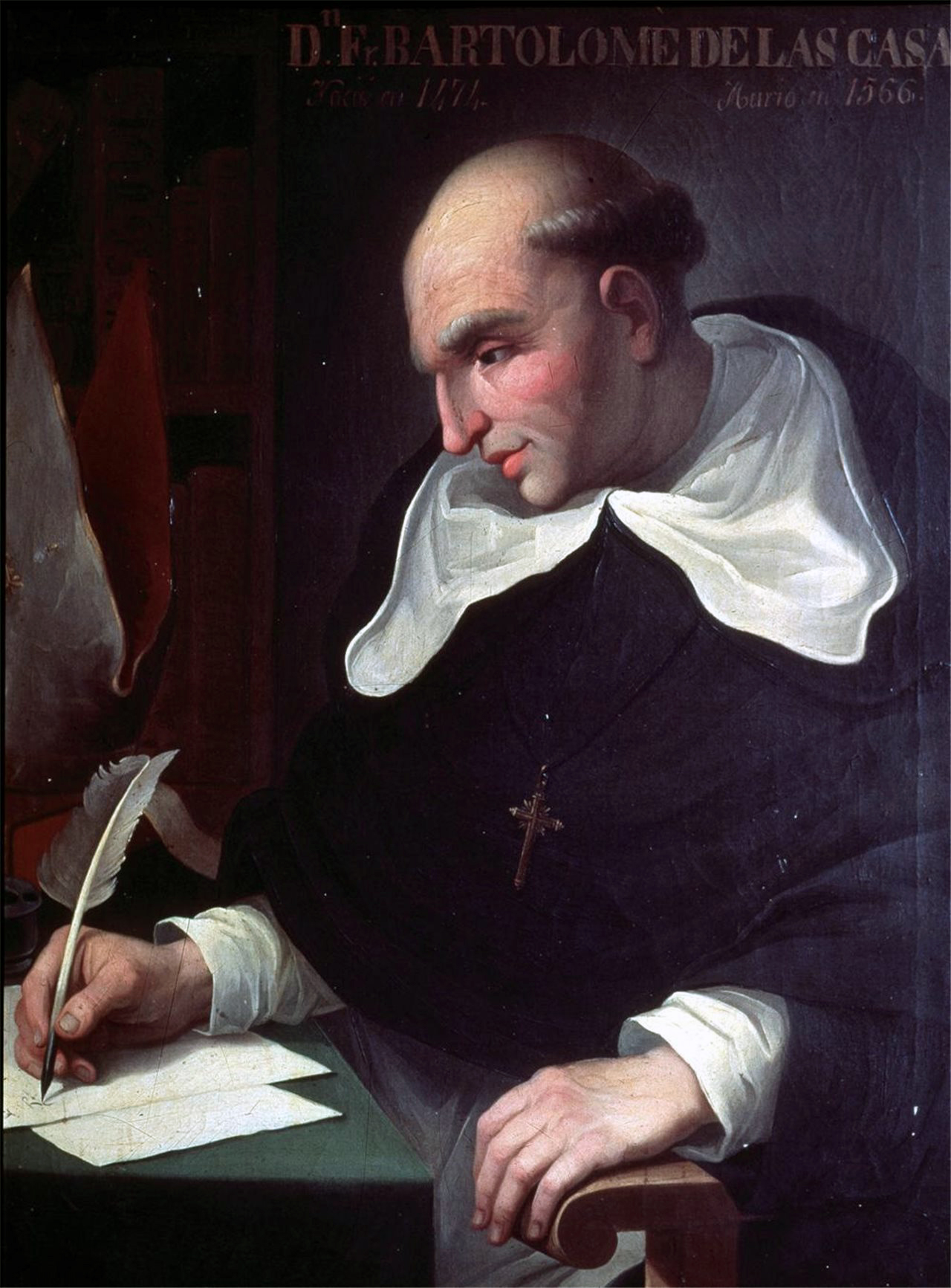

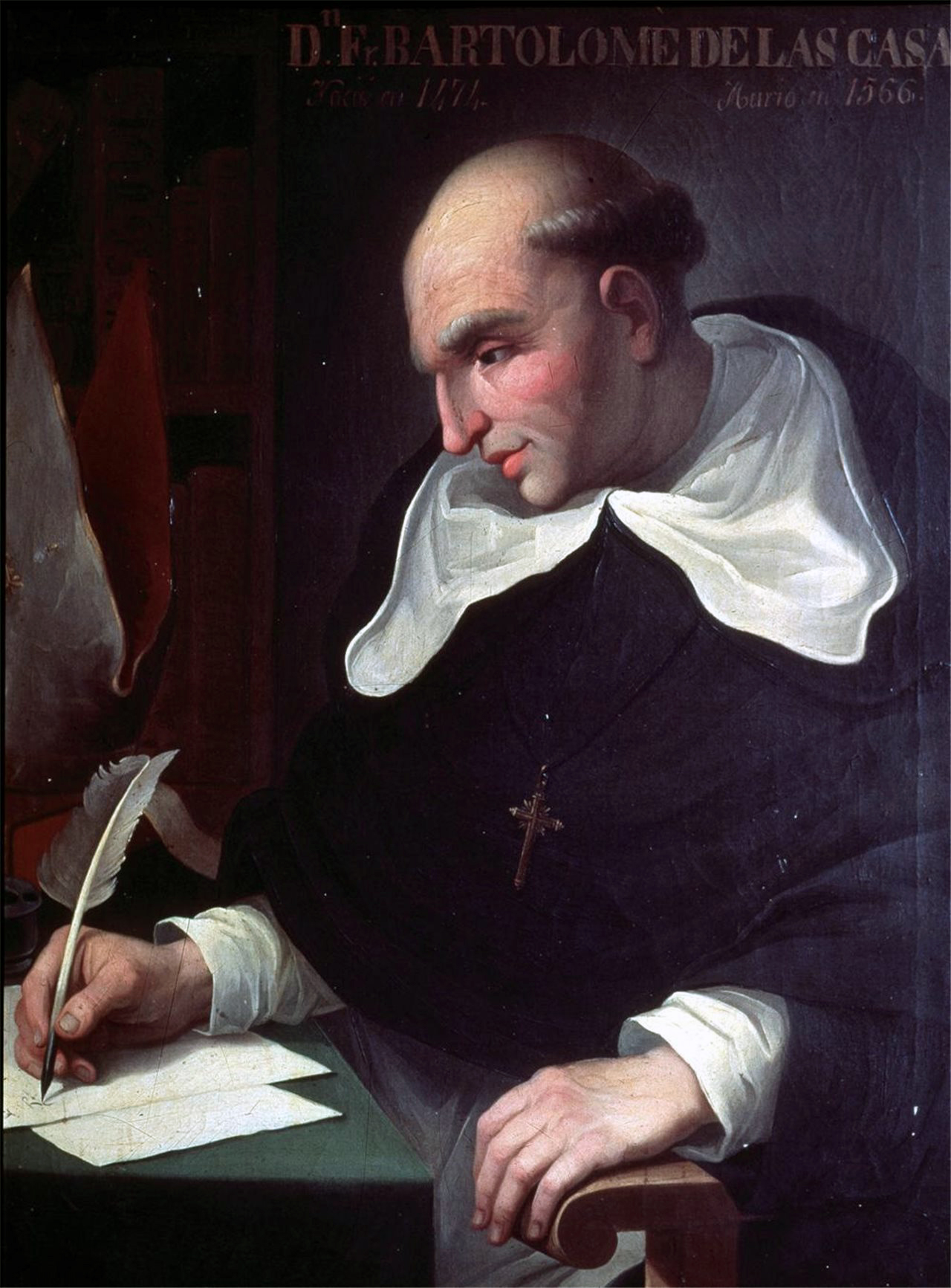

, in ''De iure belli'' Fransico pointed out that the underlying predicate conditions for a "just war" were "wholly lacking in the Indies".Salas Jr., Victor M., "Francisco de Vitoria on the ''Ius Gentium'' and the American Indios", ''Ave Maria Law Review'', 2012Vitoria adopted from Aquinas the Roman law concept of ''ius gentium'' ("the law of nations"). His defense of American Indians was based on a Scholastic understanding of the intrinsic dignity of man, a dignity he found being violated by Spain's policies in the New World. Dominican friar

Pedro de Córdoba

Pedro de Córdoba OP (c.1460–1525) was a Spanish missionary, author and inquisitor on the island of Hispaniola. He was first to denounce the Spanish system known as the '' Encomienda'', which amounted to the practical enslavement of na ...

OP (c. 1460–1525) was a Spanish missionary on the island of Hispaniola. He was first to denounce the system of forced labor known as the Encomienda, imposed on the native inhabitants.

Other important figures include Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

and Peter of Saint Joseph Betancur

Peter of Saint Joseph de Betancur (or Betancourt) y Gonzáles ( es, Pedro de San José de Betancur y Gonzáles, March 21, 1626 (Tenerife) – April 25, 1667 (Antigua Guatemala), called Hermano Pedro de San José Betancurt (''Brother Peter of ...

Catholic Universalism

Émeric Crucé

Émeric Crucé (1590–1648) was a French political writer, known for the ''Nouveau Cynée'' (1623), a pioneer work on international relations. He advocated for an international pacific body of representatives of many countries.

Life

Little spec ...

was a French monk who took the position that wars were the result of international misunderstandings and the domination of society by the warrior class, both of which could be reduced through commerce, as that brought people together. The genesis of the idea of a meeting of representatives of different nations to obtain by peaceful arbitration a settlement of differences has been traced to Crucé's 1623 work entitled ''The New Cyneas'', a discourse showing the opportunities and the means for establishing a general peace and liberty of conscience to all the world, addressed to the monarch and the sovereign princes of the time. He proposed that a city, preferably Venice, should be selected where all the Powers had ambassadors including all peoples.

Modern Church (to c. 1945)

Kulturkampf

From 1871 to 1878, Chancellor Bismarck, who controlled both the German Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, launched the "Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastic ...

" in Prussia to reduce the power of the Catholic Church in public affairs, and keep Polish Catholics under control. Thousands of priests and bishops were harassed or imprisoned, with large fines and closures of Catholic churches and schools. German was declared to be the only official language, but in practice the Poles only adhered more closely to their traditions. Catholics were angry at his systematic attacks. Unanimous in their resistance, they organized themselves to fight back politically, using their strength in other states such as Catholic Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. There was little or no violence, and the new Roman Catholic Center Party won a quarter of the seats in the ''Reichstag'' (Imperial Parliament), and its middle position on most issues allowed it to play a decisive role in the formation of majorities. The culture war gave secularists and socialists an opportunity to attack all religions, an outcome that distressed the Protestants, including Bismarck. After the death of Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

in 1878 Bismarck opened negotiations with Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

, which led to his gradual abandonment of the Kulturkampf in the early 1880s.

Caritas

The first Caritas organisation was established by Lorenz Worthmann 9 November 1897 in Germany. Other national Caritas organisations were soon formed in Switzerland (1901) and the United States (Catholic Charities, 1910). It has since grown into "Caritas Internationalis", a confederation of 165 Roman Catholic relief, development and social service organizations operating in over 200 countries and territories worldwide. Caritas Australia is involved in peacebuilding and reconciliation programs in Sri Lanka, The Philippines, Papua New Guinea and elsewhere, including Movimento de Defesa do Fevelado (MDF) which trains youth to be peacebuilders in São Paulo, Brazil in response to an increasing number of children becoming involved in drugs, organised crime and murders. It is hoped these trainees will become the next generation of leaders in their communities. In an effort to overcome many prejudices and fears between different nationalities, ethnic and religious groups. The Salzburg branch of Caritas Osterreich sponsors a Peace Camp for unprivileged children of different religious denominations from all over the Middle East. The camp takes place in a different country in the region each year. Since 1999 almost 900 children and youths from nine different countries and eighteen different religious denominations have participated in the program.Fascism and Nazism

BishopKonrad von Preysing

Johann Konrad Maria Augustin Felix, Graf von Preysing Lichtenegg-Moos (30 August 1880 – 21 December 1950) was a German prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. Considered a significant figure in Catholic resistance to Nazism, he served as ...

was one of the most firm and consistent of senior Catholics to oppose the Nazis. He and Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen (16 March 1878 – 22 March 1946), better known as ''Clemens August Graf von Galen'', was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Churc ...

, along with Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli