Catholic culture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian culture generally includes all the

/ref> During the early

Pythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe

Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2008, (page number not available – occurs toward end of Chapter 13, "The Wrap-up of Antiquity"). "It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language." They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology, and medicine.Britannica

Nestorian

/ref> Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the

Christianity had a significant impact on education and science and medicine as the church created the basis of the Western system of education, and was the sponsor of founding

Christianity had a significant impact on education and science and medicine as the church created the basis of the Western system of education, and was the sponsor of founding

p.16 and family life. Historically, '' extended families'' were the basic family unit in the Christian culture and

The architecture of cathedrals, basilicas and abbey churches is characterised by the buildings' large scale and follows one of several branching traditions of form, function and style that all ultimately derive from the Early Christian architectural traditions established in the Constantinian period.

Cathedrals in particular, as well as many

The architecture of cathedrals, basilicas and abbey churches is characterised by the buildings' large scale and follows one of several branching traditions of form, function and style that all ultimately derive from the Early Christian architectural traditions established in the Constantinian period.

Cathedrals in particular, as well as many

File:Sant Vasily cathedral in Moscow.JPG,

An

An

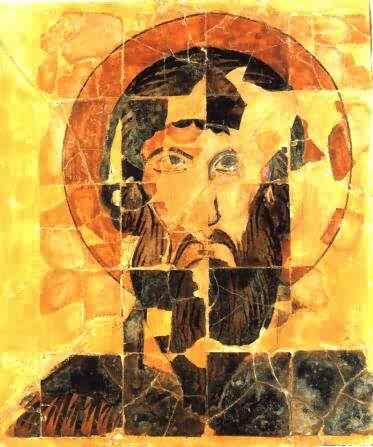

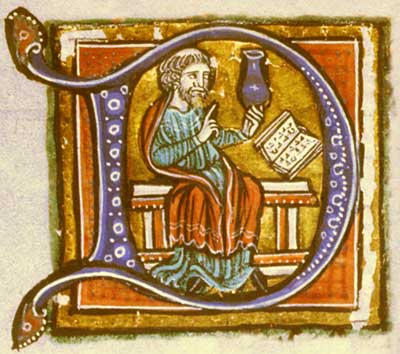

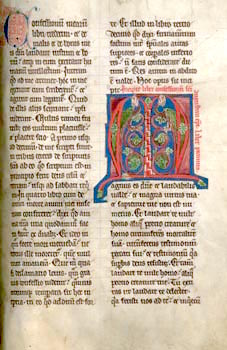

Christian art began, about two centuries after Christ, by borrowing motifs from Roman Imperial imagery, classical Greek and Roman religion and popular art.

Christian art began, about two centuries after Christ, by borrowing motifs from Roman Imperial imagery, classical Greek and Roman religion and popular art.

The dedication of

The dedication of  This achievement was checked by the controversy over the use of ''graven images'', and the proper interpretation of the Second Commandment, which led to the crisis of

This achievement was checked by the controversy over the use of ''graven images'', and the proper interpretation of the Second Commandment, which led to the crisis of

File:Gerard van Honthorst - Adoration of the Shepherds (1622).jpg, ''Adoration of the Shepherds'' by

The

The

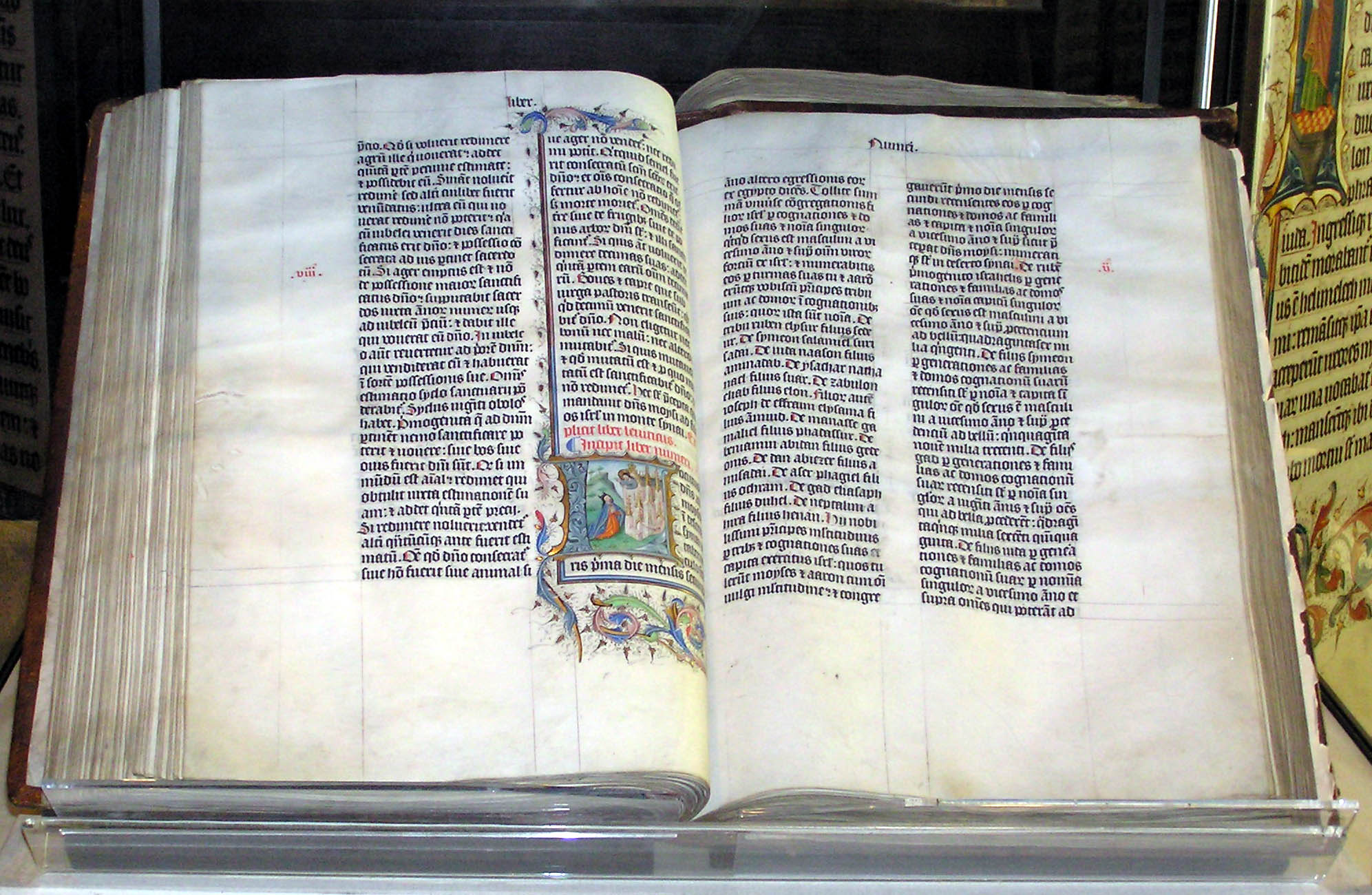

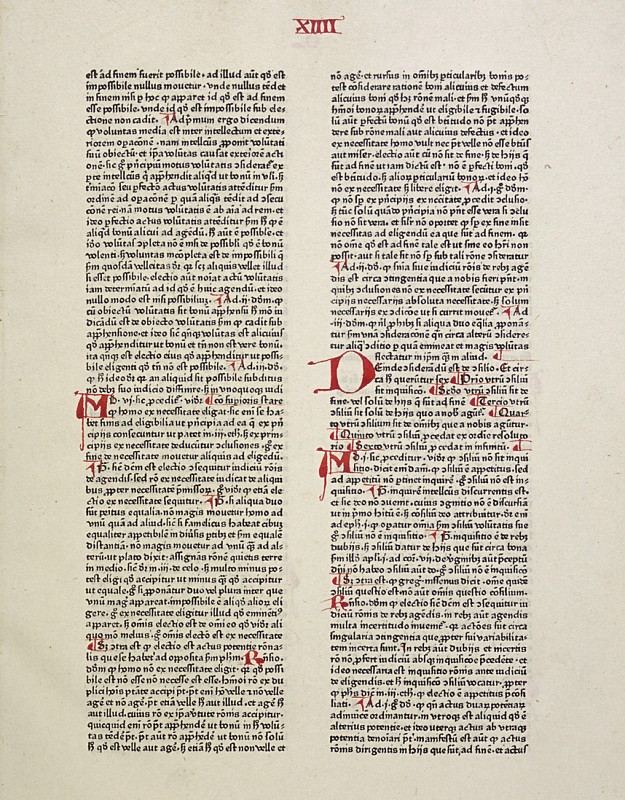

The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the

The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the  The Catholic Church founded the West's first universities, which were preceded by the schools attached to monasteries and cathedrals, and generally staffed by monks and friars.Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011 Universities began springing up in Italian towns like

The Catholic Church founded the West's first universities, which were preceded by the schools attached to monasteries and cathedrals, and generally staffed by monks and friars.Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011 Universities began springing up in Italian towns like  A Pew Center study about religion and education around the world in 2016, found that Christians ranked as the second most educated religious group around in the world after

A Pew Center study about religion and education around the world in 2016, found that Christians ranked as the second most educated religious group around in the world after

In

In

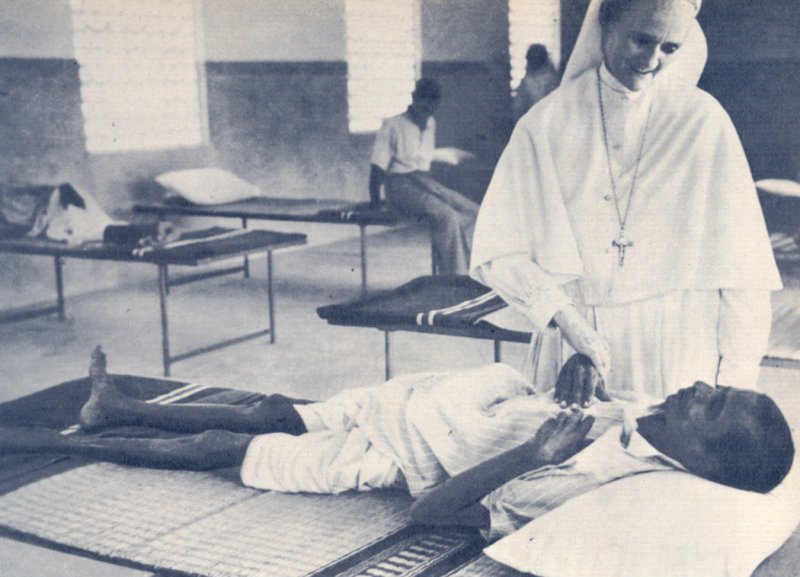

The administration of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires split and the Fall of Rome, demise of the Western Empire by the 6th century was accompanied by a series of violent invasions and precipitated the collapse of cities and civic institutions of learning, along with their links to the learning of classical Greece and Rome. For the next thousand years, medical knowledge would change very little. A scholarly medical tradition maintained itself in the more stable East, but in the West, scholarship virtually disappeared outside of the Church, where monks were aware of a dwindling range of medical texts. Hospitality was considered an obligation of Christian charity and bishops' houses and the valetudinaria of wealthier Christians were used to tend the sick. And the legacy of this early period was, in the words of Porter, that "Christianity planted the hospital: the well-endowed establishments of the Levant and the scattered houses of the West shared a common religious ethos of charity."

The

The administration of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires split and the Fall of Rome, demise of the Western Empire by the 6th century was accompanied by a series of violent invasions and precipitated the collapse of cities and civic institutions of learning, along with their links to the learning of classical Greece and Rome. For the next thousand years, medical knowledge would change very little. A scholarly medical tradition maintained itself in the more stable East, but in the West, scholarship virtually disappeared outside of the Church, where monks were aware of a dwindling range of medical texts. Hospitality was considered an obligation of Christian charity and bishops' houses and the valetudinaria of wealthier Christians were used to tend the sick. And the legacy of this early period was, in the words of Porter, that "Christianity planted the hospital: the well-endowed establishments of the Levant and the scattered houses of the West shared a common religious ethos of charity."

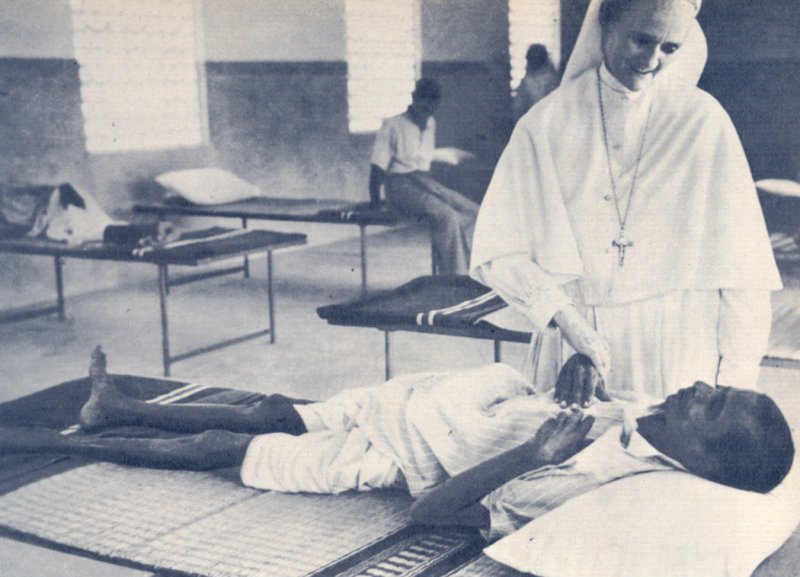

The  Geoffrey Blainey likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates. It was common for monks and clerics to practice medicine and medical students in northern European universities often took minor Holy orders. Mediaeval hospitals had a strongly Christian ethos, and were, in the words of historian of medicine Roy Porter, "religious foundations through and through", and Ecclesiastical regulations were passed to govern medicine, partly to prevent clergymen profiting from medicine.Roy Porter; ''The Greatest Benefit to Mankind - a Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present''; Harper Collins; 1997; pp. 110-112 During Europe's Age of Discovery, Catholic missionaries, notably the Jesuits, introduced the modern sciences to India, China and Japan. While persecutions continue to limit the spread of Catholic institutions to some Middle Eastern Muslim nations, and such places as the People's Republic of China and North Korea, elsewhere in Asia the church is a major provider of health care services - especially in Catholic Nations like the Philippines.

Today the Roman Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of health care services in the world. It has around 18,000 clinics, 16,000 homes for the elderly and those with special needs, and 5,500 hospitals, with 65 percent of them located in developing countries.Robert Calderisi; ''Earthly Mission - The Catholic Church and World Development''; TJ International Ltd; 2013; p.40 In 2010, the Church's Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Health Care Workers said that the Church manages 26% of the world's health care facilities. The Church's involvement in health care has ancient origins.

Geoffrey Blainey likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates. It was common for monks and clerics to practice medicine and medical students in northern European universities often took minor Holy orders. Mediaeval hospitals had a strongly Christian ethos, and were, in the words of historian of medicine Roy Porter, "religious foundations through and through", and Ecclesiastical regulations were passed to govern medicine, partly to prevent clergymen profiting from medicine.Roy Porter; ''The Greatest Benefit to Mankind - a Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present''; Harper Collins; 1997; pp. 110-112 During Europe's Age of Discovery, Catholic missionaries, notably the Jesuits, introduced the modern sciences to India, China and Japan. While persecutions continue to limit the spread of Catholic institutions to some Middle Eastern Muslim nations, and such places as the People's Republic of China and North Korea, elsewhere in Asia the church is a major provider of health care services - especially in Catholic Nations like the Philippines.

Today the Roman Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of health care services in the world. It has around 18,000 clinics, 16,000 homes for the elderly and those with special needs, and 5,500 hospitals, with 65 percent of them located in developing countries.Robert Calderisi; ''Earthly Mission - The Catholic Church and World Development''; TJ International Ltd; 2013; p.40 In 2010, the Church's Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Health Care Workers said that the Church manages 26% of the world's health care facilities. The Church's involvement in health care has ancient origins.

The medieval era was disparagingly treated by the Renaissance humanists, who saw it as a barbaric "middle" period between the classical age of Greek and Roman culture, and the "rebirth" or ''renaissance'' of classical culture. Yet this period of nearly a thousand years was the longest period of philosophical development in Europe, and possibly the richest. Jorge Gracia has argued that "in intensity, sophistication, and achievement, the philosophical flowering in the thirteenth century could be rightly said to rival the golden age of Greek philosophy in the fourth century B.C."Gracia, p. 1

Some problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and unity of God, the object of theology and metaphysics, the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.

Philosophers from the Middle Ages include the Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo, Boethius, Anselm of Canterbury, Anselm, Gilbert of Poitiers, Peter Abelard, Roger Bacon, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham and Jean Buridan; the Jewish philosophers Maimonides and Gersonides; and the

The medieval era was disparagingly treated by the Renaissance humanists, who saw it as a barbaric "middle" period between the classical age of Greek and Roman culture, and the "rebirth" or ''renaissance'' of classical culture. Yet this period of nearly a thousand years was the longest period of philosophical development in Europe, and possibly the richest. Jorge Gracia has argued that "in intensity, sophistication, and achievement, the philosophical flowering in the thirteenth century could be rightly said to rival the golden age of Greek philosophy in the fourth century B.C."Gracia, p. 1

Some problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and unity of God, the object of theology and metaphysics, the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.

Philosophers from the Middle Ages include the Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo, Boethius, Anselm of Canterbury, Anselm, Gilbert of Poitiers, Peter Abelard, Roger Bacon, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham and Jean Buridan; the Jewish philosophers Maimonides and Gersonides; and the

Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with Newtonian mechanics appear quite different from later attempts at reconciliation with the newer scientific ideas of evolution or Theory of relativity, relativity.''Religion and Science'', John Habgood, Mills & Brown, 1964, pp., 11, 14–16, 48–55, 68–69, 90–91, 87 Many early interpretations of evolution polarized themselves around a ''survival of the fittest, struggle for existence''. These ideas were significantly countered by later findings of universal sociobiology, patterns of biological cooperation. According to John Habgood, all man really knows here is that the universe seems to be a mix of good and evil, beauty and pain, and that suffering may somehow be part of the process of creation. Habgood holds that Christians should not be surprised that suffering may be used creatively by God, given their faith in the symbol of the Christian cross, Cross.

Robert John Russell has examined consonance and dissonance between modern physics, evolutionary biology, and Christian theology.

Christian philosophy, Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on. Also the sense that God created the world as a self operating system is what motivated many Christians throughout the Middle Ages to investigate nature.

Modern historians of science such as J.L. Heilbron, Alistair Cameron Crombie, David C Lindberg, David Lindberg, Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein (historian), Thomas Goldstein, and Ted Davis have reviewed the popular notion that medieval Christianity was a negative influence in the development of civilization and science. In their views, not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian", not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. He was not unlike other medieval theologians who sought out reason in the effort to defend his faith. Some of today's scholars, such as Stanley Jaki, have claimed that Christianity with its particular worldview, was a crucial factor for the emergence of modern science. Some scholars and historians attributes

Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with Newtonian mechanics appear quite different from later attempts at reconciliation with the newer scientific ideas of evolution or Theory of relativity, relativity.''Religion and Science'', John Habgood, Mills & Brown, 1964, pp., 11, 14–16, 48–55, 68–69, 90–91, 87 Many early interpretations of evolution polarized themselves around a ''survival of the fittest, struggle for existence''. These ideas were significantly countered by later findings of universal sociobiology, patterns of biological cooperation. According to John Habgood, all man really knows here is that the universe seems to be a mix of good and evil, beauty and pain, and that suffering may somehow be part of the process of creation. Habgood holds that Christians should not be surprised that suffering may be used creatively by God, given their faith in the symbol of the Christian cross, Cross.

Robert John Russell has examined consonance and dissonance between modern physics, evolutionary biology, and Christian theology.

Christian philosophy, Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on. Also the sense that God created the world as a self operating system is what motivated many Christians throughout the Middle Ages to investigate nature.

Modern historians of science such as J.L. Heilbron, Alistair Cameron Crombie, David C Lindberg, David Lindberg, Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein (historian), Thomas Goldstein, and Ted Davis have reviewed the popular notion that medieval Christianity was a negative influence in the development of civilization and science. In their views, not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian", not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. He was not unlike other medieval theologians who sought out reason in the effort to defend his faith. Some of today's scholars, such as Stanley Jaki, have claimed that Christianity with its particular worldview, was a crucial factor for the emergence of modern science. Some scholars and historians attributes

List of Christians in science and technology, Christian Scholars and Scientists have made noted contributions to science and technology fields, as well as Medicine, Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Isaac NewtonRichard S. Westfall – Indiana University Robert Boyle, Francis Bacon, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Emanuel Swedenborg, Alessandro Volta, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Antoine Lavoisier, André-Marie Ampère, John Dalton, James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, Louis Pasteur, Michael Faraday, and J. J. Thomson.

Isaac Newton, for example, believed that gravitation, gravity caused the planets to revolve about the Sun, and credited God with the Isaac Newton's religious views, design. In the concluding General Scholium to the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he wrote: "This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being." Other famous founders of science who adhered to Christian beliefs include Galileo, Johannes Kepler, and Blaise Pascal.

Prominent modern scientists advocating Christian belief include Nobel Prize–winning physicists Charles Townes (

List of Christians in science and technology, Christian Scholars and Scientists have made noted contributions to science and technology fields, as well as Medicine, Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Isaac NewtonRichard S. Westfall – Indiana University Robert Boyle, Francis Bacon, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Emanuel Swedenborg, Alessandro Volta, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Antoine Lavoisier, André-Marie Ampère, John Dalton, James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, Louis Pasteur, Michael Faraday, and J. J. Thomson.

Isaac Newton, for example, believed that gravitation, gravity caused the planets to revolve about the Sun, and credited God with the Isaac Newton's religious views, design. In the concluding General Scholium to the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he wrote: "This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being." Other famous founders of science who adhered to Christian beliefs include Galileo, Johannes Kepler, and Blaise Pascal.

Prominent modern scientists advocating Christian belief include Nobel Prize–winning physicists Charles Townes (

100 Years of Nobel Prizes

p. 59 65.3% in Nobel Prize in Physics, Physics, 62% in Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Medicine, 54% in Nobel Prize in Economics, Economics.

Byzantine science was essentially classical science, and played an important and crucial role in the Greek contributions to the Islamic world, transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy. Many of the most distinguished classical scholars held high office in the

Byzantine science was essentially classical science, and played an important and crucial role in the Greek contributions to the Islamic world, transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy. Many of the most distinguished classical scholars held high office in the

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the Roman Catholic position on the relationship between science and religion is one of harmony, and has maintained the teaching of

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the Roman Catholic position on the relationship between science and religion is one of harmony, and has maintained the teaching of  The Catholic Cistercians, Cistercian order used its own Cistercian numerals, numbering system, which could express numbers from 0 to 9999 in a single sign. According to one modern Cistercian, "enterprise and entrepreneurial spirit" have always been a part of the order's identity, and the Cistercians "were catalysts for development of a market economy" in 12th-century Europe. Until the Industrial Revolution, most of the technological advances in Europe were made in the monasteries. According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods. Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement [that] could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries. The English science historian James Burke (science historian), James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill near Arles in the fourth of his ten-part ''Connections (British documentary), Connections'' TV series, called "Faith in Numbers". The Cistercians made major contributions to culture and technology in medieval Europe: Cistercian architecture is considered one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture; and the Cistercians were the main force of technological diffusion in fields such as agriculture and hydraulic engineering.

One view, first propounded by The Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment philosophers, asserts that the Church's doctrines are entirely superstitious and have hindered the progress of civilization. Communist states have made similar arguments in their education in order to inculcate a negative view of Catholicism (and religion in general) in their citizens. The most famous incidents cited by such critics are the Church's condemnations of the teachings of Copernicus, Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler.

The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were Jesuits, have been among the leading lights in astronomy, genetics, geomagnetism, meteorology, seismology, and solar physics, becoming some of the "fathers" of these sciences. Examples include important churchmen such as the Augustinians, Augustinian abbot Gregor Mendel (pioneer in the study of genetics), Roger Bacon (a Franciscan friar who was one of the early advocates of the scientific method), and Belgian priest Georges Lemaître (the first to propose the Big Bang theory). Other notable priest scientists have included Albertus Magnus,

The Catholic Cistercians, Cistercian order used its own Cistercian numerals, numbering system, which could express numbers from 0 to 9999 in a single sign. According to one modern Cistercian, "enterprise and entrepreneurial spirit" have always been a part of the order's identity, and the Cistercians "were catalysts for development of a market economy" in 12th-century Europe. Until the Industrial Revolution, most of the technological advances in Europe were made in the monasteries. According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods. Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement [that] could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries. The English science historian James Burke (science historian), James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill near Arles in the fourth of his ten-part ''Connections (British documentary), Connections'' TV series, called "Faith in Numbers". The Cistercians made major contributions to culture and technology in medieval Europe: Cistercian architecture is considered one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture; and the Cistercians were the main force of technological diffusion in fields such as agriculture and hydraulic engineering.

One view, first propounded by The Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment philosophers, asserts that the Church's doctrines are entirely superstitious and have hindered the progress of civilization. Communist states have made similar arguments in their education in order to inculcate a negative view of Catholicism (and religion in general) in their citizens. The most famous incidents cited by such critics are the Church's condemnations of the teachings of Copernicus, Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler.

The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were Jesuits, have been among the leading lights in astronomy, genetics, geomagnetism, meteorology, seismology, and solar physics, becoming some of the "fathers" of these sciences. Examples include important churchmen such as the Augustinians, Augustinian abbot Gregor Mendel (pioneer in the study of genetics), Roger Bacon (a Franciscan friar who was one of the early advocates of the scientific method), and Belgian priest Georges Lemaître (the first to propose the Big Bang theory). Other notable priest scientists have included Albertus Magnus,

Protestantism had an important influence on science. According to the Merton Thesis there was a positive correlation between the rise of

Protestantism had an important influence on science. According to the Merton Thesis there was a positive correlation between the rise of

Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States

' New York, The Free Press, 1977, p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two-thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-) Overall, Protestant have won a total of 84.2% of all the American Nobel Prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemistry, 60% in Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Medicine, 58.6% in Nobel Prize in Physics, Physics, between 1901 and 1972.

The notion of "Christian finance" refers to banking and financial activities which came into existence several centuries ago. Whether the activities of the Knights Templar (12th century), Mount of piety, Mounts of Piety (appeared in 1462) or the Apostolic Chamber attached directly to the Vatican, a number of operations of a banking nature (money loan, guarantee, etc.) or a financial nature (issuance of securities, investments) is proved, despite the prohibition of usury and the Church distrust against exchange activities (opposed to production activities).

Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development. Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the 20th century, referring to the Scholasticism, Scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the 'founders' of scientific economics." Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements.

The Protestant concept of God and man allows believers to use all their God-given faculties, including the power of reason. That means that they are allowed to explore God's creation and, according to Genesis 2:15, make use of it in a responsible and sustainable way. Thus a cultural climate was created that greatly enhanced the development of the humanities and the sciences. Another consequence of the Protestant understanding of man is that the believers, in gratitude for their election and redemption in Christ, are to follow God's commandments. Industry, frugality, calling, discipline, and a strong sense of responsibility are at the heart of their moral code. In particular, John Calvin rejected luxury. Therefore, craftsmen, industrialists, and other businessmen were able to reinvest the greater part of their profits in the most efficient machinery and the most modern production methods that were based on progress in the sciences and technology. As a result, productivity grew, which led to increased profits and enabled employers to pay higher wages. In this way, the economy, the sciences, and technology reinforced each other. The chance to participate in the economic success of technological inventions was a strong incentive to both inventors and investors. The

The notion of "Christian finance" refers to banking and financial activities which came into existence several centuries ago. Whether the activities of the Knights Templar (12th century), Mount of piety, Mounts of Piety (appeared in 1462) or the Apostolic Chamber attached directly to the Vatican, a number of operations of a banking nature (money loan, guarantee, etc.) or a financial nature (issuance of securities, investments) is proved, despite the prohibition of usury and the Church distrust against exchange activities (opposed to production activities).

Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development. Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the 20th century, referring to the Scholasticism, Scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the 'founders' of scientific economics." Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements.

The Protestant concept of God and man allows believers to use all their God-given faculties, including the power of reason. That means that they are allowed to explore God's creation and, according to Genesis 2:15, make use of it in a responsible and sustainable way. Thus a cultural climate was created that greatly enhanced the development of the humanities and the sciences. Another consequence of the Protestant understanding of man is that the believers, in gratitude for their election and redemption in Christ, are to follow God's commandments. Industry, frugality, calling, discipline, and a strong sense of responsibility are at the heart of their moral code. In particular, John Calvin rejected luxury. Therefore, craftsmen, industrialists, and other businessmen were able to reinvest the greater part of their profits in the most efficient machinery and the most modern production methods that were based on progress in the sciences and technology. As a result, productivity grew, which led to increased profits and enabled employers to pay higher wages. In this way, the economy, the sciences, and technology reinforced each other. The chance to participate in the economic success of technological inventions was a strong incentive to both inventors and investors. The

Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christians, and traditional

Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christians, and traditional

File:Lucia procession.jpg, Saint Lucy's Day procession in Sweden

File:Bgnr.jpg, Celebrating the Epiphany (holiday), Epiphany in Bulgaria

File:Venezia carnevale 7.jpg, Carnival of Venice

File:Easter eggs - straw decoration.jpg, Easter eggs are a popular cultural symbol of Easter

File:Maria Stma de la Estrella Jaén.jpg, Procession of pasos during the Holy Week in Spain

Roman Catholic theology enumerates seven sacraments: Baptism (infant baptism, Christening), Confirmation (Catholic Church), Confirmation (Chrismation), Eucharist in the Catholic Church, Eucharist (Holy Communion, Communion), Sacrament of Penance (Catholic Church), Penance (Reconciliation), Anointing of the Sick (Catholic Church), Anointing of the Sick (before the Second Vatican Council generally called Extreme Unction), Marriage (Catholic Church), Matrimony

In Christian belief and practice, a ''sacrament'' is a Rite (Christianity), rite, instituted by Christ, that mediates divine grace, grace, constituting a Sacred mysteries, sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word ''sacramentum'', which was used to translate the Greek word for ''mystery''. Views concerning both what rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament vary among Christian denominations and traditions.Cross/Livingstone. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. p. 1435f.

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist (or Holy Communion), however, the majority of Christians also recognize five additional sacraments: Confirmation (Christian sacrament), Confirmation (Chrismation in the Orthodox tradition), Holy orders (ordination), Penance (or Confession (religion), Confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony (see Christian views on marriage).

Taken together, these are the Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Seven Sacraments as recognized by churches in the High Church tradition—notably Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Independent Catholic Churches, Independent Catholic, Old Catholic, many Anglican sacraments, Anglicans, and some Lutherans. Most other denominations and traditions typically affirm only Baptism and Eucharist as sacraments, while some Protestant groups, such as the Quakers, reject sacramental theology. Christian denominations, such as Baptists, which believe these rites do not communicate grace, prefer to call Baptism and Holy Communion ''Ordinance (Christian), ordinances'' rather than sacraments.

Today, most Christian denominations are neutral about religious male circumcision, neither requiring it nor forbidding it. The practice is customary among the Coptic Christian, Coptic, Ethiopian Orthodox, Ethiopian, and Eritrean Orthodox Churches, and also some other African churches.Customary in some Coptic and other churches:

*"The Coptic Christians in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians— two of the oldest surviving forms of Christianity— retain many of the features of early Christianity, including male circumcision. Circumcision is not prescribed in other forms of Christianity ... Some Christian churches in South Africa oppose the practice, viewing it as a pagan ritual, while others, including the Nomiya church in Kenya, require circumcision for membership and participants in focus group discussions in Zambia and Malawi mentioned similar beliefs that Christians should practice circumcision since Jesus was circumcised and the Bible teaches the practice."

*"The decision that Christians need not practice circumcision is recorded in ; there was never, however, a prohibition of circumcision, and it is practiced by Coptic Christians.

Roman Catholic theology enumerates seven sacraments: Baptism (infant baptism, Christening), Confirmation (Catholic Church), Confirmation (Chrismation), Eucharist in the Catholic Church, Eucharist (Holy Communion, Communion), Sacrament of Penance (Catholic Church), Penance (Reconciliation), Anointing of the Sick (Catholic Church), Anointing of the Sick (before the Second Vatican Council generally called Extreme Unction), Marriage (Catholic Church), Matrimony

In Christian belief and practice, a ''sacrament'' is a Rite (Christianity), rite, instituted by Christ, that mediates divine grace, grace, constituting a Sacred mysteries, sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word ''sacramentum'', which was used to translate the Greek word for ''mystery''. Views concerning both what rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament vary among Christian denominations and traditions.Cross/Livingstone. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. p. 1435f.

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist (or Holy Communion), however, the majority of Christians also recognize five additional sacraments: Confirmation (Christian sacrament), Confirmation (Chrismation in the Orthodox tradition), Holy orders (ordination), Penance (or Confession (religion), Confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony (see Christian views on marriage).

Taken together, these are the Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Seven Sacraments as recognized by churches in the High Church tradition—notably Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Independent Catholic Churches, Independent Catholic, Old Catholic, many Anglican sacraments, Anglicans, and some Lutherans. Most other denominations and traditions typically affirm only Baptism and Eucharist as sacraments, while some Protestant groups, such as the Quakers, reject sacramental theology. Christian denominations, such as Baptists, which believe these rites do not communicate grace, prefer to call Baptism and Holy Communion ''Ordinance (Christian), ordinances'' rather than sacraments.

Today, most Christian denominations are neutral about religious male circumcision, neither requiring it nor forbidding it. The practice is customary among the Coptic Christian, Coptic, Ethiopian Orthodox, Ethiopian, and Eritrean Orthodox Churches, and also some other African churches.Customary in some Coptic and other churches:

*"The Coptic Christians in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians— two of the oldest surviving forms of Christianity— retain many of the features of early Christianity, including male circumcision. Circumcision is not prescribed in other forms of Christianity ... Some Christian churches in South Africa oppose the practice, viewing it as a pagan ritual, while others, including the Nomiya church in Kenya, require circumcision for membership and participants in focus group discussions in Zambia and Malawi mentioned similar beliefs that Christians should practice circumcision since Jesus was circumcised and the Bible teaches the practice."

*"The decision that Christians need not practice circumcision is recorded in ; there was never, however, a prohibition of circumcision, and it is practiced by Coptic Christians.

"circumcision"

The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–05. Even though most Christian denominations does not require male circumcision, male circumcision is widely in many predominantly Christianity by country, Christian countries and many Christian communities. Worship can be varied for special events like baptisms or weddings in the service or significant Calendar of saints, feast days. In the Early Christianity, early church, Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for the Eucharistic part of the worship. In many churches today, adults and children will separate for all or some of the service to receive age-appropriate teaching. Such children's worship is often called Sunday school or Sabbath school (Sunday schools are often held before rather than during services).

Christian culture puts notable emphasis on the family, and according to the work of scholars Max Weber, Alan Macfarlane, Steven Ozment, Jack Goody and Peter Laslett, the huge transformation that led to modern marriage in Western democracies was "fueled by the religio-cultural value system provided by elements of Judaism, early

Christian culture puts notable emphasis on the family, and according to the work of scholars Max Weber, Alan Macfarlane, Steven Ozment, Jack Goody and Peter Laslett, the huge transformation that led to modern marriage in Western democracies was "fueled by the religio-cultural value system provided by elements of Judaism, early  The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints puts notable emphasis on the family, and the distinctive concept of a united family which lives and progresses forever is at the core of Latter-day Saint doctrine. Church members are encouraged to marry and have children, and as a result, Latter-day Saint families tend to be larger than average. All sexual activity outside of marriage is considered a serious sin. All homosexual activity is considered sinful and same-sex marriages are not performed or supported by the LDS Church. Latter-day Saint fathers who hold the Priesthood (LDS Church), priesthood typically baby blessing, name and bless their children shortly after birth to formally give the child a name and generate a church record for them. Mormons tend to be very family-oriented and have strong connections across generations and with extended family, reflective of their belief that families can be Sealing (Mormonism), sealed together beyond death. Mormons also have a strict law of chastity, requiring abstention from sexual relations outside heterosexual marriage and fidelity within marriage.

A Pew Center study about Religion and Living arrangements around the world in 2019, found that Christians around the world live in somewhat smaller households, on average, than non-Christians (4.5 vs. 5.1 members). 34% of world's Christian population live in two parent families with minor children, while 29% live in household with extended families, 11% live as couples without other family members, 9% live in household with least one child over the age of 18 with one or two parents, 7% live alone, and 6% live in single parent households. Christians in Asia and Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean,

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints puts notable emphasis on the family, and the distinctive concept of a united family which lives and progresses forever is at the core of Latter-day Saint doctrine. Church members are encouraged to marry and have children, and as a result, Latter-day Saint families tend to be larger than average. All sexual activity outside of marriage is considered a serious sin. All homosexual activity is considered sinful and same-sex marriages are not performed or supported by the LDS Church. Latter-day Saint fathers who hold the Priesthood (LDS Church), priesthood typically baby blessing, name and bless their children shortly after birth to formally give the child a name and generate a church record for them. Mormons tend to be very family-oriented and have strong connections across generations and with extended family, reflective of their belief that families can be Sealing (Mormonism), sealed together beyond death. Mormons also have a strict law of chastity, requiring abstention from sexual relations outside heterosexual marriage and fidelity within marriage.

A Pew Center study about Religion and Living arrangements around the world in 2019, found that Christians around the world live in somewhat smaller households, on average, than non-Christians (4.5 vs. 5.1 members). 34% of world's Christian population live in two parent families with minor children, while 29% live in household with extended families, 11% live as couples without other family members, 9% live in household with least one child over the age of 18 with one or two parents, 7% live alone, and 6% live in single parent households. Christians in Asia and Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean,

In mainstream Nicene Christianity, there is no restriction on kinds of animals that can be eaten. This practice stems from Peter's vision of a sheet with animals, in which Saint Peter "sees a sheet containing animals of every description lowered from the sky." Nonetheless, the New Testament does give a few guidelines about the consumption of meat, practiced by the Christian Church today; one of these is not consuming food knowingly offered to pagan Idolatry, idols, a conviction that the Primitive Church, early Church Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria and

In mainstream Nicene Christianity, there is no restriction on kinds of animals that can be eaten. This practice stems from Peter's vision of a sheet with animals, in which Saint Peter "sees a sheet containing animals of every description lowered from the sky." Nonetheless, the New Testament does give a few guidelines about the consumption of meat, practiced by the Christian Church today; one of these is not consuming food knowingly offered to pagan Idolatry, idols, a conviction that the Primitive Church, early Church Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria and

The Bible has many rituals of purification relating to menstruation, childbirth, religion and sexuality, sexual relations, keri, nocturnal emission, Zav, unusual bodily fluids, Tzaraath, skin disease, death, and korban, animal sacrifices. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church prescribes several kinds of hand washing for example after leaving the latrine, lavatory or bathhouse, or before prayer, or after eating a meal. The women in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church are prohibited from entering the church temple during menses; and the men do not enter a church the day after they have had intercourse with their wives.

Christianity has always placed a strong Ablution in Christianity, emphasis on hygiene, Despite the denunciation of the mixed bathing style of Roman pools by early Christian clergy, as well as the pagan custom of women naked bathing in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing, which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the Church Fathers, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian. The Church also built public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near Christian monasticism, monasteries and pilgrimage sites; also, the popes situated baths within church

The Bible has many rituals of purification relating to menstruation, childbirth, religion and sexuality, sexual relations, keri, nocturnal emission, Zav, unusual bodily fluids, Tzaraath, skin disease, death, and korban, animal sacrifices. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church prescribes several kinds of hand washing for example after leaving the latrine, lavatory or bathhouse, or before prayer, or after eating a meal. The women in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church are prohibited from entering the church temple during menses; and the men do not enter a church the day after they have had intercourse with their wives.

Christianity has always placed a strong Ablution in Christianity, emphasis on hygiene, Despite the denunciation of the mixed bathing style of Roman pools by early Christian clergy, as well as the pagan custom of women naked bathing in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing, which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the Church Fathers, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian. The Church also built public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near Christian monasticism, monasteries and pilgrimage sites; also, the popes situated baths within church

Christian pop culture (or Christian popular culture), is the vernacular Christian culture that prevails in any given society. The content of popular culture is determined by the daily interactions, needs and desires, and cultural 'movements' that make up everyday lives of Christians. It can include any number of practices, including those pertaining to cooking, clothing, mass media and the many facets of entertainment such as sports and literature

In modern urban mass societies, Christian pop culture has been crucially shaped by the development of industrial mass production, the introduction of new technologies of sound and image broadcasting and recording, and the growth of mass media industries—the film, Broadcasting, broadcast radio and television, radio, video game, and the book publishing industries, as well as the print and electronic news media.

Items of Christian pop culture most typically appeal to a broad spectrum of Christians. Some argue that broad-appeal items dominate Christian pop culture because profit-making Christian companies that produce and sell items of Christian pop culture attempt to maximize their profits by emphasizing broadly appealing items. And yet the situation is more complex. To take the example of Christian pop music, it is not the case that the music industry can impose any product they wish. In fact, highly popular types of music have often first been elaborated in small, counter-cultural circles such as Christian punk rock or Christian rap.

Because the Christian pop industry is significantly smaller than the secular pop industry, a few organizations and companies dominate the market and have a strong influence over what is dominant within the industry.

Another source of Christian pop culture which makes it differ from pop culture is the influence from mega churches. Christian pop culture reflects the current popularity of megachurches, but also the uniting of smaller community churches. The culture has been led by Hillsong Church in particular, which resides in many countries including Australia, France, and the United Kingdom.

Christian pop culture (or Christian popular culture), is the vernacular Christian culture that prevails in any given society. The content of popular culture is determined by the daily interactions, needs and desires, and cultural 'movements' that make up everyday lives of Christians. It can include any number of practices, including those pertaining to cooking, clothing, mass media and the many facets of entertainment such as sports and literature

In modern urban mass societies, Christian pop culture has been crucially shaped by the development of industrial mass production, the introduction of new technologies of sound and image broadcasting and recording, and the growth of mass media industries—the film, Broadcasting, broadcast radio and television, radio, video game, and the book publishing industries, as well as the print and electronic news media.

Items of Christian pop culture most typically appeal to a broad spectrum of Christians. Some argue that broad-appeal items dominate Christian pop culture because profit-making Christian companies that produce and sell items of Christian pop culture attempt to maximize their profits by emphasizing broadly appealing items. And yet the situation is more complex. To take the example of Christian pop music, it is not the case that the music industry can impose any product they wish. In fact, highly popular types of music have often first been elaborated in small, counter-cultural circles such as Christian punk rock or Christian rap.

Because the Christian pop industry is significantly smaller than the secular pop industry, a few organizations and companies dominate the market and have a strong influence over what is dominant within the industry.

Another source of Christian pop culture which makes it differ from pop culture is the influence from mega churches. Christian pop culture reflects the current popularity of megachurches, but also the uniting of smaller community churches. The culture has been led by Hillsong Church in particular, which resides in many countries including Australia, France, and the United Kingdom.

The Christian film industry is an umbrella term for films containing a Christianity, Christian themed message or moral, produced by Christian filmmakers to a Christian audience, and films produced by non-Christians with Christian audiences in mind. They are often interdenominational films, but can also be films targeting a specific denomination of Christianity. Popular mainstream studio productions of films with strong Christian messages or biblical stories, like ''Ben-Hur (1959 film), Ben-Hur'', ''The Ten Commandments (1956 film), The Ten Commandments'', ''The Passion of the Christ'', ''The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe'', ''The Book of Eli'', ''Machine Gun Preacher'', ''The Star (2017 film), The Star'', ''The Flying House (TV series), The Flying House'', ''Superbook'' and ''Silence (2016 film), Silence'', are not specifically part of the Christian film industry, being more agnostic about their audiences' religious beliefs. These films generally also have a much higher budget, production values and better known film stars, and are received more favourably with film critics.

The 2014 film ''God's Not Dead (film), God's Not Dead'' is one of the all-time most successful independent Christian films and the 2015 film ''War Room (film), War Room'' became a List of 2015 box office number-one films in the United States, Box Office number-one film.

The Christian film industry is an umbrella term for films containing a Christianity, Christian themed message or moral, produced by Christian filmmakers to a Christian audience, and films produced by non-Christians with Christian audiences in mind. They are often interdenominational films, but can also be films targeting a specific denomination of Christianity. Popular mainstream studio productions of films with strong Christian messages or biblical stories, like ''Ben-Hur (1959 film), Ben-Hur'', ''The Ten Commandments (1956 film), The Ten Commandments'', ''The Passion of the Christ'', ''The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe'', ''The Book of Eli'', ''Machine Gun Preacher'', ''The Star (2017 film), The Star'', ''The Flying House (TV series), The Flying House'', ''Superbook'' and ''Silence (2016 film), Silence'', are not specifically part of the Christian film industry, being more agnostic about their audiences' religious beliefs. These films generally also have a much higher budget, production values and better known film stars, and are received more favourably with film critics.

The 2014 film ''God's Not Dead (film), God's Not Dead'' is one of the all-time most successful independent Christian films and the 2015 film ''War Room (film), War Room'' became a List of 2015 box office number-one films in the United States, Box Office number-one film.

Televangelism (wikt:tele-, tele- "distance" and "evangelism", meaning "Christian ministry, ministry", sometimes called ''teleministry'') is the use of media, specifically radio and television, to communicate

Televangelism (wikt:tele-, tele- "distance" and "evangelism", meaning "Christian ministry, ministry", sometimes called ''teleministry'') is the use of media, specifically radio and television, to communicate

A Christianophile is a person who expresses a strong interest in or appreciation for Christianity, Christian culture, Christian history,

A Christianophile is a person who expresses a strong interest in or appreciation for Christianity, Christian culture, Christian history,

Rethinking Folk Religion in Hong Kong: Social Capital, Civic Community and the State

''. Hong Kong Baptist University. Macau,

cultural practice

Cultural practice is the manifestation of a culture or sub-culture, especially in regard to the traditional and customary practices of a particular ethnic or other cultural groups.

The term is gaining in importance due to the increased controver ...

s which have developed around the religion of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

. There are variations in the application of Christian beliefs in different cultures and traditions.

Christian culture has influenced and assimilated much from the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

, Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

,Caltron J.H Hayas, ''Christianity and Western Civilization'' (1953), Stanford University Press, p.2: "That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization – the civilization of western Europe and of America— have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo – Graeco – Christianity, Catholic and Protestant." Middle Eastern

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europea ...

, Slavic, Caucasian, and possibly from Indian culture

Indian culture is the heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, belief systems, political systems, artifacts and technologies that originated in or are associated with the ethno-linguistically diverse India. The term ...

.The Culture of Kerala/ref> During the early

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

has been divided in the pre-existing Greek East and Latin West. Consequently, different versions of the Christian cultures arose with their own rites and practices, Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, in particular, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

and Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. Western culture, throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture. Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence on various cultures, such as in Africa and Asia.

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ� ...

have made a noted contributions to human progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension ...

in a broad and diverse range of fields, both historically and in modern times, including the science and technology, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, fine arts and architecture, politics, literatures, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

, philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

, ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concer ...

, humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

and business. According to ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

in its various forms as their religious preference.Baruch A. Shalev, ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' (2003), Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p.57: between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religions. Most (65.4%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference.

Cultural influence

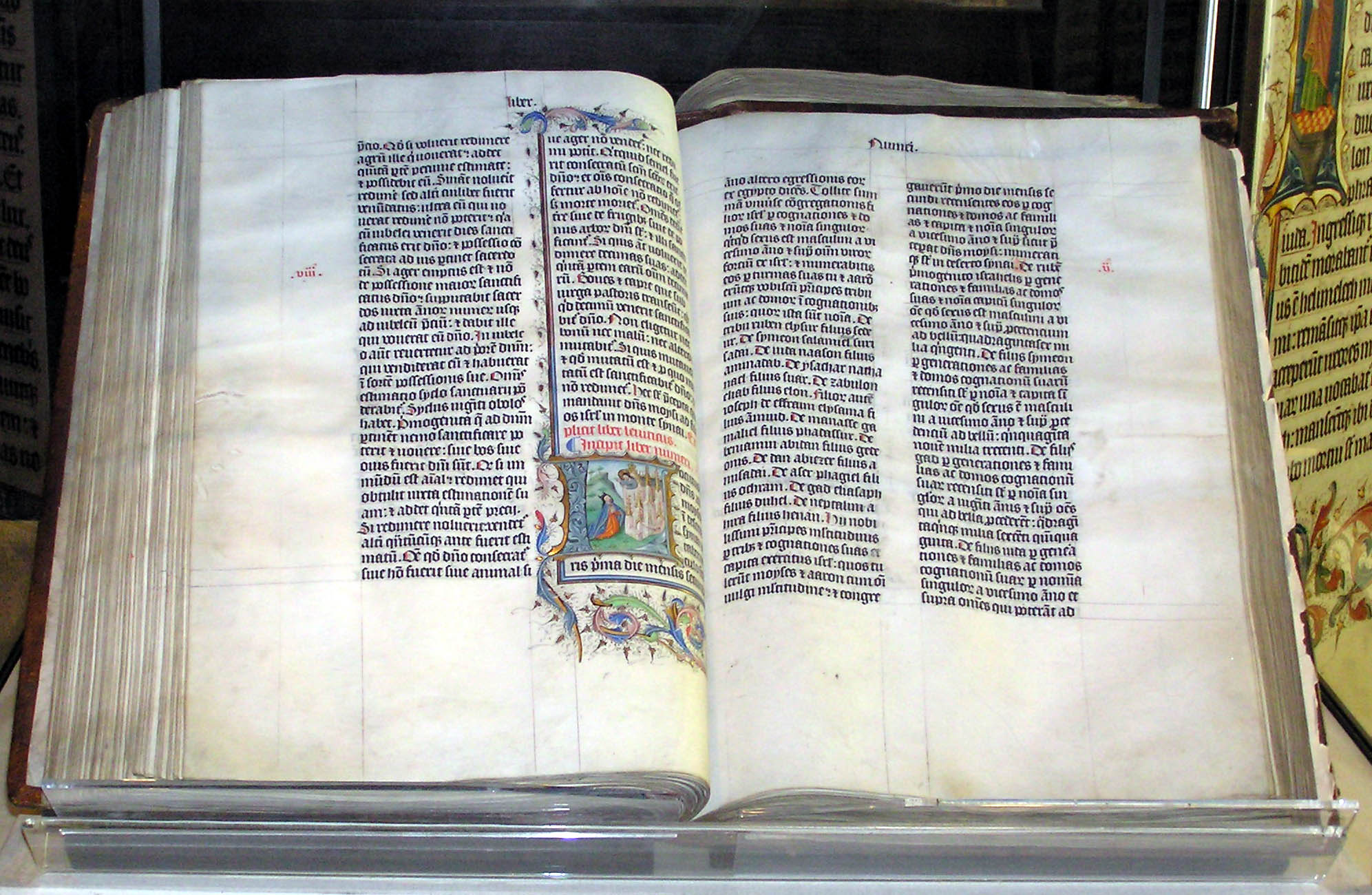

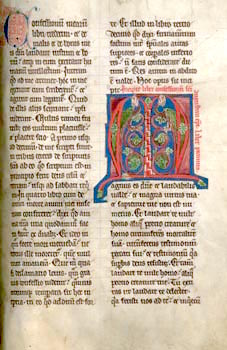

TheBible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

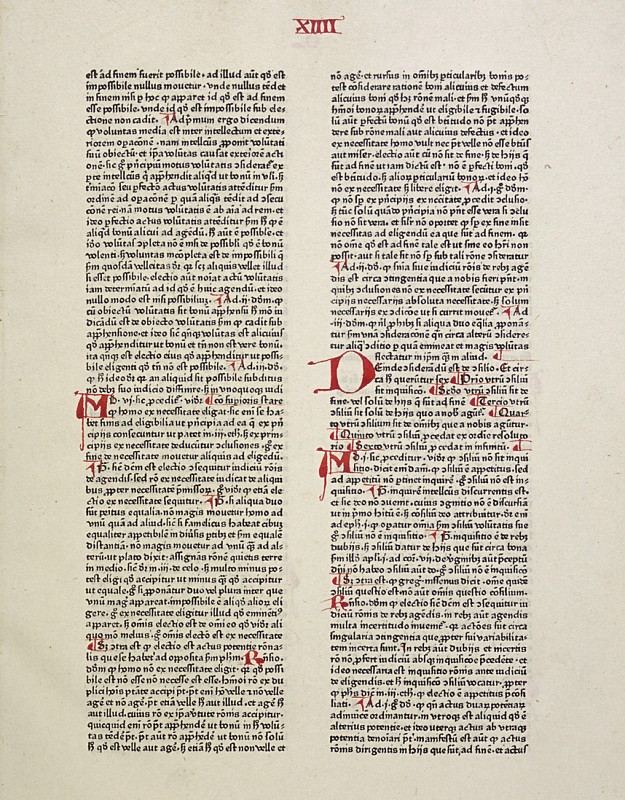

has had a profound influence on Western civilization and on cultures around the globe; it has contributed to the formation of Western law, art, texts, and education. With a literary tradition spanning two millennia, the Bible is one of the most influential works ever written. From practices of personal hygiene to philosophy and ethics, the Bible has directly and indirectly influenced politics and law, war and peace, sexual morals, marriage and family life, toilet etiquette, letters and learning, the arts, economics, social justice, medical care and more. The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe. It marked the start of the " Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed ...

was the first book printed in Europe using movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

.

Since the spread of Christianity from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004 ...

during the early Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

has been divided in the pre-existing Greek East and Latin West. Consequently, different versions of the Christian cultures arose with their own rites and practices, centered around the cities such as Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

(Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholi ...

) and Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, whose communities was called Western or Latin Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

, and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

(Eastern Christianity

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent an ...

), Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

(Syriac Christianity

Syriac Christianity ( syr, ܡܫܝܚܝܘܬܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܬܐ / ''Mšiḥoyuṯo Suryoyto'' or ''Mšiḥāyūṯā Suryāytā'') is a distinctive branch of Eastern Christianity, whose formative theological writings and traditional liturgies are ex ...

), Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South Ca ...

( Indian Christianity) and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, among others, whose communities were called Eastern or Oriental Christendom. The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

was one of the peaks in Christian history and Christian civilization. From the 11th to 13th centuries, Latin Christendom rose to the central role of the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

and Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

.

Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence on various cultures, such as in Africa, the Near East, Middle East, Central Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Scholars and intellectuals agree Christians in the Middle East have made significant contributions to Arab and Islamic civilization since the introduction of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

, and they have had a significant impact contributing the culture of the Mashriq, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Eastern Christian scientists and scholars of the medieval Islamic world (particularly Jacobite and Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

Christians) contributed to the Arab Islamic civilization during the reign of the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

and the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

, by translating works of Greek philosophers to Syriac and afterwards, to Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

.Hill, Donald. ''Islamic Science and Engineering''. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. , p.4Ferguson, KittPythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe

Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2008, (page number not available – occurs toward end of Chapter 13, "The Wrap-up of Antiquity"). "It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language." They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology, and medicine.Britannica

Nestorian

/ref> Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization." The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

has played a prominent role in the history and culture of Eastern and Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

, the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

, and the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

. The Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represen ...

have played a prominent role in the history and culture of Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopi ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and parts of the Middle East