Carolingian Art on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carolingian art comes from the

Carolingian art comes from the  There was for the first time a thoroughgoing attempt in Northern Europe to revive and emulate classical Mediterranean art forms and styles, that resulted in a blending of classical and Northern elements in a sumptuous and dignified style, in particular introducing to the North confidence in representing the human figure, and setting the stage for the rise of

There was for the first time a thoroughgoing attempt in Northern Europe to revive and emulate classical Mediterranean art forms and styles, that resulted in a blending of classical and Northern elements in a sumptuous and dignified style, in particular introducing to the North confidence in representing the human figure, and setting the stage for the rise of

Having established an Empire as large as the

Having established an Empire as large as the

The most numerous surviving works of the Carolingian renaissance are

The most numerous surviving works of the Carolingian renaissance are

The Court School of Charlemagne (also known as the Ada School) produced the earliest manuscripts, including the

The Court School of Charlemagne (also known as the Ada School) produced the earliest manuscripts, including the  The

The

Luxury Carolingian manuscripts were intended to have

Luxury Carolingian manuscripts were intended to have

Sources attest to the abundance of wall paintings seen in churches and palaces, most of which have not survived. Records of inscriptions show that their subject matter was primarily religious.

Sources attest to the abundance of wall paintings seen in churches and palaces, most of which have not survived. Records of inscriptions show that their subject matter was primarily religious.

''

''

"Carolingian art"

In ''

Carolingian Art

',

Carolingian art comes from the

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

There was for the first time a thoroughgoing attempt in Northern Europe to revive and emulate classical Mediterranean art forms and styles, that resulted in a blending of classical and Northern elements in a sumptuous and dignified style, in particular introducing to the North confidence in representing the human figure, and setting the stage for the rise of

There was for the first time a thoroughgoing attempt in Northern Europe to revive and emulate classical Mediterranean art forms and styles, that resulted in a blending of classical and Northern elements in a sumptuous and dignified style, in particular introducing to the North confidence in representing the human figure, and setting the stage for the rise of Romanesque art

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic Art, Gothic style in the 12th century, or later depending on region. The preceding period is known as the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 1 ...

and eventually Gothic art

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern, Southern and ...

in the West. The Carolingian era is part of the period in medieval art

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, gen ...

sometimes called the "Pre-Romanesque

Pre-Romanesque art and architecture is the period in European art from either the emergence of the Merovingian kingdom in about 500 AD or from the Carolingian Renaissance in the late 8th century, to the beginning of the 11th century Romanesqu ...

". After a rather chaotic interval following the Carolingian period, the new Ottonian dynasty

The Ottonian dynasty (german: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs (919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after the ...

revived Imperial art from about 950, building on and further developing Carolingian style in Ottonian art

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and nort ...

.

Overview

Having established an Empire as large as the

Having established an Empire as large as the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

of the day, and rivaling in size the old Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

, the Carolingian court must have been conscious that they lacked an artistic style to match these or even the post-antique (or "sub-antique" as Ernst Kitzinger called it) art still being produced in small quantities in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and a few other centres in Italy, which Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

knew from his campaigns, and where he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

in Rome in 800.

As symbolic representative of Rome he sought the ''renovatio'' (revival) of Roman culture and learning in the West, and needed an art capable of telling stories and representing figures with an effectiveness which ornamental Germanic Migration period art

Migration Period art denotes the artwork of the Germanic peoples during the Migration period (c. 300 – 900). It includes the Migration art of the Germanic tribes on the continent, as well the start of the Insular art or Hiberno-Saxon art of th ...

could not. He wished to establish himself as the heir to the great rulers of the past, to emulate and symbolically link the artistic achievements of Early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

culture with his own.

But it was more than a conscious desire to revive ancient Roman culture. During Charlemagne's reign the Byzantine Iconoclasm

The Byzantine Iconoclasm ( gr, Εικονομαχία, Eikonomachía, lit=image struggle', 'war on icons) were two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial a ...

controversy was dividing the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. He supported the Western church's consistent refusal to follow iconoclasm; the Libri Carolini

The ''Libri Carolini'' ("Charles' books"), more correctly ''Opus Caroli regis contra synodum'' ("The work of King Charles against the Synod"), is a work in four books composed on the command of Charlemagne in the mid 790s to refute the conclusions ...

sets out the position of his court circle, no doubt under his direction. With no inhibitions from a cultural memory of Mediterranean pagan idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of a cult image or "idol" as though it were God. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, the Baháʼí Faith, and Islam) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the A ...

, he introduced the first Christian monumental religious sculpture, a momentous precedent for Western art.

Reasonable numbers of Carolingian illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s and small-scale sculptures, mostly in ivory, have survived, but far fewer examples of metalwork, mosaics and frescoes and other types of work. Many manuscripts in particular are copies or reinterpretations of Late Antique or Byzantine models, nearly all now lost, and the nature of the influence of specific models on individual Carolingian works remains a perennial topic in art history. As well as these influences, the extravagant energy of Insular art added a definite flavour to Carolingian work, which sometimes used interlaced decoration, and followed more cautiously the insular freedom in allowing decoration to spread around and into the text on the page of a manuscript.

With the end of Carolingian rule around 900, high quality artistic production greatly declined for about three generations in the Empire. By the later 10th century with the Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in 9 ...

reform movement, and a revived spirit for the idea of Empire, art production began again. New Pre-Romanesque styles appeared in Germany with the Ottonian art

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and nort ...

of the next stable dynasty, in England with late Anglo-Saxon art

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norma ...

, after the threat from the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s was removed, and in Spain.

Illuminated manuscripts

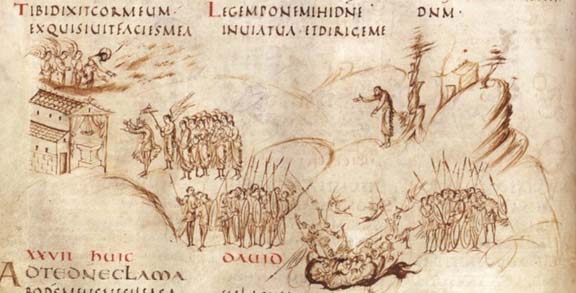

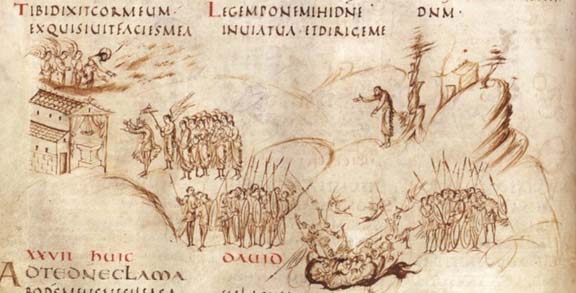

The most numerous surviving works of the Carolingian renaissance are

The most numerous surviving works of the Carolingian renaissance are illuminated manuscripts

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

. A number of luxury manuscripts, mostly Gospel book

A Gospel Book, Evangelion, or Book of the Gospels (Greek: , ''Evangélion'') is a codex or bound volume containing one or more of the four Gospels of the Christian New Testament – normally all four – centering on the life of Jesus of Nazar ...

s, have survived, decorated with a relatively small number of full-page miniatures, often including evangelist portrait

Evangelist portraits are a specific type of miniature included in ancient and mediaeval illuminated manuscript Gospel Books, and later in Bibles and other books, as well as other media. Each Gospel of the Four Evangelists, the books of Matthew, ...

s, and lavish canon tables

Eusebian canons, Eusebian sections or Eusebian apparatus, also known as Ammonian sections, are the system of dividing the four Gospels used between late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The divisions into chapters and verses used in modern texts ...

, following the precedent of the Insular art of Britain and Ireland. Narrative images and especially cycles are rarer, but many exist, mostly of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, especially Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

; New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

scenes are more often found on the ivory relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

s on the covers. The oversized and heavily decorated initials of Insular art were adopted, and the historiated initial

A historiated initial is an initial, an enlarged letter at the beginning of a paragraph or other section of text, that contains a picture. Strictly speaking, a historiated initial depicts an identifiable figure or a specific scene, while an in ...

further developed, with small narrative scenes seen for the first time towards the end of the period—notably in the Drogo Sacramentary

The Drogo Sacramentary (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de FranceMS lat. 9428 is a Carolingian illuminated manuscript on vellum from 850 AD, one of the monuments of Carolingian book illumination. It is a sacramentary, a book containing all th ...

. Luxury manuscripts were given treasure binding

A treasure binding or jewelled bookbinding is a luxurious book cover using metalwork in gold or silver, jewels, or ivory, perhaps in addition to more usual bookbinding material for book-covers such as leather, velvet, or other cloth. The act ...

s or rich covers with jewels set in gold and carved ivory panels, and, as in Insular art, were prestige objects kept in the church or treasury, and a different class of object from the working manuscripts kept in the library, where some initials might be decorated, and pen drawings added in a few places. A few of the grandest imperial manuscripts were written on purple parchment

Purple parchment or purple vellum refers to parchment dyed purple; codex purpureus refers to manuscripts written entirely or mostly on such parchment. The lettering may be in gold or silver. Later the practice was revived for some especially gran ...

. The Bern Physiologus is a relatively rare example of a secular manuscript heavily illustrated with fully painted miniatures, lying in between these two classes, and perhaps produced for the private library of an important individual, as was the Vatican Terence. The Utrecht Psalter

The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS Bibl. Rhenotraiectinae I Nr 32.) is a ninth-century illuminated manuscript, illuminated psalter which is a key masterpiece of Carolingian art; it is probably the most valuable manuscript ...

, stands alone as a very heavily illustrated library version of the Psalms done in pen and wash, and almost certainly copied from a much earlier manuscript.

Other liturgical works were sometimes produced in luxury manuscripts, such as sacramentaries, but no Carolingian Bible is decorated as heavily as the Late Antique examples that survive in fragments. Teaching books such as theological, historical, literary and scientific works from ancient authors were copied and generally only illustrated in ink, if at all. The Chronography of 354

The ''Chronograph of 354'' (or "Chronography"), also known as the ''Calendar of 354'', is a compilation of chronological and calendrical texts produced in 354 AD for a wealthy Roman Christian named Valentinus by the calligrapher and illustrator ...

was a Late Roman manuscript that apparently was copied in the Carolingian period, though this copy seems to have been lost in the 17th century.

Centres of illumination

Carolingian manuscripts are presumed to have been produced largely or entirely by clerics, in a few workshops around the Carolingian Empire, each with its own style that developed based on the artists and influences of that particular location and time. Manuscripts often have inscriptions, not necessarily contemporary, as to who commissioned them, and which church or monastery they were given to, but few dates or names and locations of those producing them. The surviving manuscripts have been assigned, and often reassigned, to workshops by scholars, and the controversies attending this process have largely died down. The earliest workshop was the Court School of Charlemagne; then aRheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

ian style, which became the most influential of the Carolingian period; a Touronian style; a Drogo style; and finally a Court School of Charles the Bald. These are the major centres, but others exist, characterized by the works of art produced there.

The Court School of Charlemagne (also known as the Ada School) produced the earliest manuscripts, including the

The Court School of Charlemagne (also known as the Ada School) produced the earliest manuscripts, including the Godescalc Evangelistary

The Godescalc Evangelistary, Godescalc Sacramentary, Godescalc Gospels, or Godescalc Gospel Lectionary (Paris, BNF. acquisitions nouvelles lat.1203) is an illuminated manuscript in Latin made by the Frankish scribe Godescalc and today kept in th ...

(781–783); the Lorsch Gospels

The ''Codex Aureus of Lorsch'' or Lorsch Gospels (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 50, and Alba Iulia, Biblioteca Documenta Batthyaneum, s.n.) is an illuminated Gospel Book written in Latin between 778 and 820, roughly coinciding with th ...

(778–820); the Ada Gospels

The Ada Gospels (Trier, Stadtbibliothek, Codex 22) is a late eighth century or early ninth century Carolingian gospel book in the Stadtbibliothek, Trier, Germany. The manuscript contains a dedication to Charlemagne's sister Ada, from where it ge ...

; the Soissons Gospels The Gospels of St. Medard de Soissons (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS lat. 8850) is a 9th-century illuminated manuscript and is a product of the Court School of the Carolingian Renaissance. The codex was produced before 827 when it was given to ...

; the Harley Golden Gospels

The Harley Golden Gospels, British Library, Harley MS 2788, is a Carolingian illuminated manuscript Gospel book produced in about 800–825, probably in Aachen, Germany. It is one of the manuscripts attributed to the "Ada School", which is named ...

(800-820); and the Vienna Coronation Gospels

The Vienna Coronation Gospels, also known simply as the Coronation Gospels (), is a late 8th century illuminated Gospel Book produced at the court of Charlemagne in Aachen.Kunsthistorisches 1991, p. 166. It was used by the future emperor at his c ...

; ten manuscripts in total are usually recognised. The Court School manuscripts were ornate and ostentatious, and reminiscent of 6th-century ivories and mosaics from Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

, Italy. They were the earliest Carolingian manuscripts and initiated a revival of Roman classicism, yet still maintained Migration Period art

Migration Period art denotes the artwork of the Germanic peoples during the Migration period (c. 300 – 900). It includes the Migration art of the Germanic tribes on the continent, as well the start of the Insular art or Hiberno-Saxon art of th ...

(Merovingian and Insular) traditions in their basically linear presentation, with no concern for volume and spatial relationships.

In the early 9th-century Archbishop Ebbo of Rheims

Ebbo or Ebo ( – 20 March 851) was the Archbishop of Rheims from 816 until 835 and again from 840 to 841. He was born a German serf on the royal demesne of Charlemagne. He was educated at his court and became the librarian and councillo ...

, at Hautvillers

Hautvillers is a commune in the Marne department in north-eastern France.

The Abbey of St. Peter which existed here until the French Revolution was the home of the famous Dom Perignon, a Benedictine monk whose work in wine-making helped to deve ...

(near Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

), assembled artists and transformed Carolingian art to something entirely new. The Gospel book of Ebbo

The Ebbo Gospels (Épernay, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 1) is an early Carolingian illuminated Gospel book known for an unusual, energetic style of illustration. The book was produced in the ninth century at the Benedictine Abbaye Saint-Pierre ...

(816–835) was painted with swift, fresh and vibrant brush strokes, evoking an inspiration and energy unknown in classical Mediterranean forms. Other books associated with the Rheims school include the Utrecht Psalter

The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS Bibl. Rhenotraiectinae I Nr 32.) is a ninth-century illuminated manuscript, illuminated psalter which is a key masterpiece of Carolingian art; it is probably the most valuable manuscript ...

, which was perhaps the most important of all Carolingian manuscripts, and the '' Bern Physiologus'', the earliest Latin edition of the Christian allegorical

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

text on animals. The expressive animations of the Rheims school, in particular the Utrecht Psalter with its naturalistic expressive figurine line drawings, would have influence on northern medieval art for centuries to follow, into the Romanesque period.

Another style developed at the monastery of St Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

, in which large Bibles were illustrated based on Late Antique bible illustrations. Three large Touronian Bibles were created, the last, and best, example was made about 845/846 for Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a ser ...

, called the Vivian Bible

The Firstfor disambiguation with the Second Bible of Charles the Bald, BNF Lat. 2, dated between 871 and 873. Bible of Charles the Bald ( BNF Lat. 1), also known as the Vivian Bible, is a Carolingian-era Bible commissioned by Count Vivian of T ...

. The Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

School was cut short by the invasion of the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

in 853, but its style had already left a permanent mark on other centers in the Carolingian Empire.

The

The diocese of Metz

The Diocese of Metz ( la, Dioecesis Metensis; french: Diocèse de Metz) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in France. In the Middle Ages it was a prince-bishopric of the Holy Roman Empire, a ''de facto ...

was another center of Carolingian art. Between 850 and 855 a sacramentary

In the Western Church of the Early and High Middle Ages, a sacramentary was a book used for liturgical services and the mass by a bishop or priest. Sacramentaries include only the words spoken or sung by him, unlike the missals of later cent ...

was made for Bishop Drogo called the Drogo Sacramentary

The Drogo Sacramentary (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de FranceMS lat. 9428 is a Carolingian illuminated manuscript on vellum from 850 AD, one of the monuments of Carolingian book illumination. It is a sacramentary, a book containing all th ...

. The illuminated "historiated" decorated initials (see image this page) were to have influence into the Romanesque period and were a harmonious union of classical lettering with figural scenes.

In the second half of the 9th century the traditions of the first half continued. A number of richly decorated Bibles were made for Charles the Bald, fusing Late Antiquity forms with the styles developed at Rheims and Tours. It was during this time a Franco-Saxon style appeared in the north of France, integrating Hiberno-Saxon interlace, and would outlast all other Carolingian styles into the next century.

Charles the Bald, like his grandfather, also established a Court School. Its location is uncertain but several manuscripts are attributed to it, with the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (870) being the last and most spectacular. It contained Touronian and Rheimsian elements, but fused with the style that characterized Charlemagne's Court School more formal manuscripts.

With the death of Charles the Bald patronage for manuscripts declined, signaling the beginning of the end, but some work did continue for a while. The Abbey of St. Gall

The Abbey of Saint Gall (german: Abtei St. Gallen) is a dissolved abbey (747–1805) in a Catholic religious complex in the city of St. Gallen in Switzerland. The Carolingian-era monastery existed from 719, founded by Saint Othmar on the spot ...

created the Folchard Psalter (872) and the Golden Psalter (883). This Gallish style was unique, but lacked the level of technical mastery seen in other regions.

Sculpture and metalwork

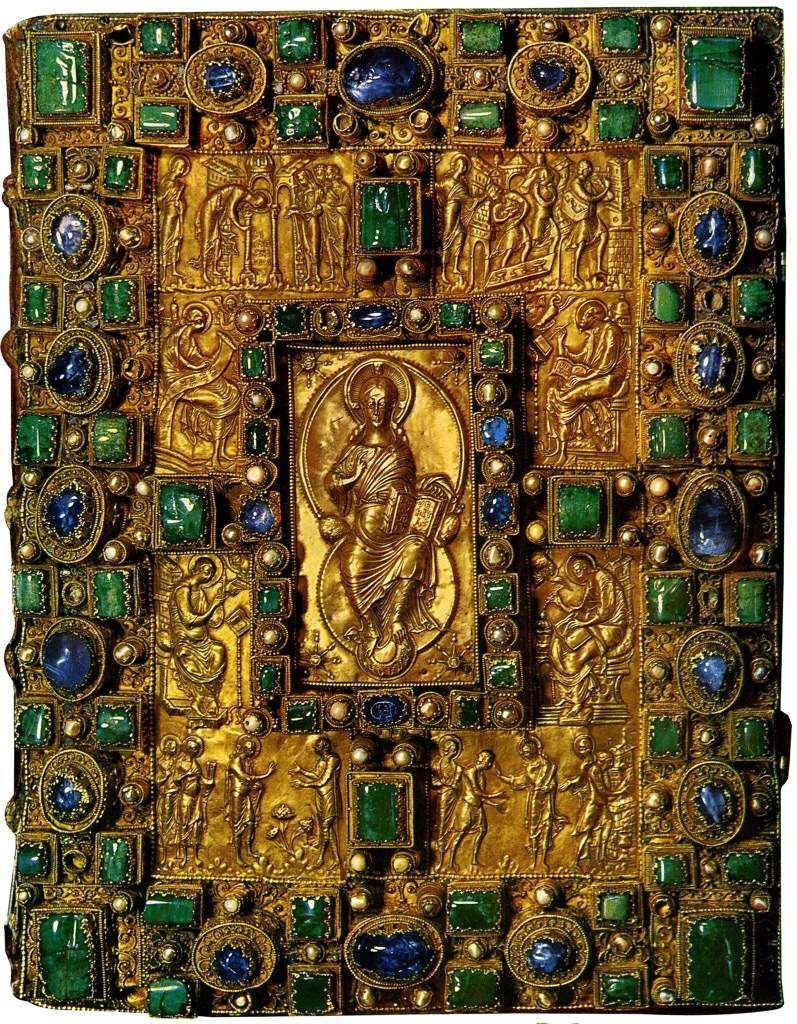

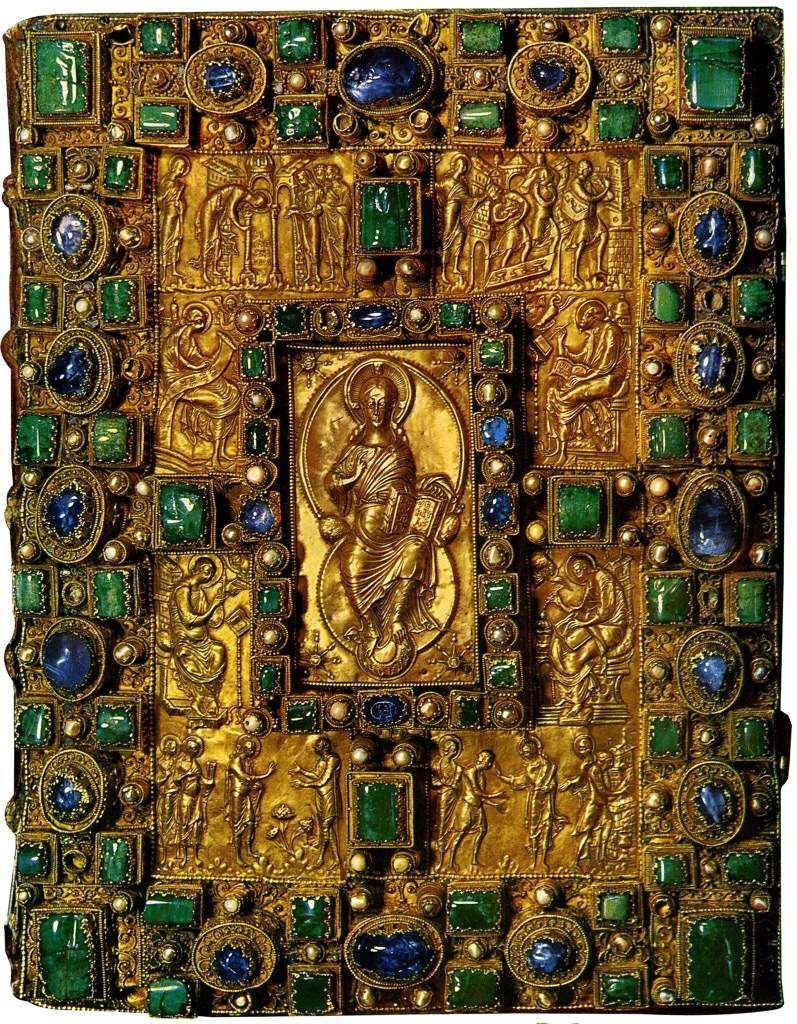

Luxury Carolingian manuscripts were intended to have

Luxury Carolingian manuscripts were intended to have treasure binding

A treasure binding or jewelled bookbinding is a luxurious book cover using metalwork in gold or silver, jewels, or ivory, perhaps in addition to more usual bookbinding material for book-covers such as leather, velvet, or other cloth. The act ...

s—ornate covers in precious metal set with jewels around central carved ivory panels—sometimes these were donated some time after the manuscript itself was produced. Only a few such covers have survived intact, but many of the ivory panels survive detached, where the covers have been broken up for their materials. The subjects were often narrative religious scenes in vertical sections, largely derived from Late Antique paintings and carvings, as were those with more hieratic images derived from consular diptych

In Late Antiquity, a consular diptych was a type of diptych intended as a de-luxe commemorative object. The diptychs were generally in ivory, wood or metal and decorated with rich relief sculpture. A consular diptych was commissioned by a ''consu ...

s and other imperial art, such as the front and back covers of the Lorsch Gospels

The ''Codex Aureus of Lorsch'' or Lorsch Gospels (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 50, and Alba Iulia, Biblioteca Documenta Batthyaneum, s.n.) is an illuminated Gospel Book written in Latin between 778 and 820, roughly coinciding with th ...

, which adapt a 6th-century Imperial triumph to the triumph of Christ and the Virgin.

Important Carolingian examples of goldsmith's work include the upper cover of the Lindau Gospels

The Lindau Gospels is an illuminated manuscript in the Morgan Library in New York, which is important for its illuminated text, but still more so for its treasure binding, or metalwork covers, which are of different periods. The oldest ele ...

; the cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which can be precisely dated to 870, is probably a product of the same workshop, though there are differences of style. This workshop is associated with the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Charles II (the Bald), and often called his "Palace School". Its location (if it had a fixed one) remains uncertain and much discussed, but Saint-Denis Abbey

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

outside Paris is one leading possibility. The Arnulf Ciborium

Arnulf is a masculine German given name.

It is composed of the Germanic elements ''arn'' "eagle" and ''ulf'' "wolf".

The ''-ulf, -olf'' suffix was an extremely frequent element in Germanic onomastics and from an early time was perceived as a mere ...

(a miniature architectural ciborium rather than the vessel for hosts), now in the Munich Residenz

The Residenz (, ''Residence'') in central Munich is the former royal palace of the Wittelsbach monarchs of Bavaria. The Residenz is the largest city palace in Germany and is today open to visitors for its architecture, room decorations, and displ ...

, is the third major work in the group; all three have fine relief figures in repoussé gold. Another work associated with the workshop is the frame of an antique serpentine dish in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

. Recent scholars tend to group the Lindau Gospels and the Arnulf Ciborium in closer relation to each other than the Codex Aureus to either.

Charlemagne revived large-scale bronze casting when he created a foundry at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

which cast the doors for his palace chapel, in imitation of Roman designs. The chapel also had a now lost life-size crucifix, with the figure of Christ in gold, the first known work of this type, which was to become so important a feature of medieval church art. Probably a wooden figure was mechanically gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

, as with the Ottonian Golden Madonna of Essen

The Golden Madonna of Essen is a sculpture of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. It is a wooden core covered with sheets of thin gold leaf. The piece is part of the treasury of Essen Cathedral, formerly the church of Essen Abbey, in North Rhi ...

.

One of the finest examples of Carolingian goldsmiths' work is the Golden Altar (824–859), a ''paliotto

An ''antependium'' (from Latin ''ante-'' and ''pendēre'' "to hang before"; pl: ''antependia''), also known as a ''parament'' or ''hanging'', or, when speaking specifically of the hanging for the altar, an altar frontal (Latin: ''pallium altaris ...

'', in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio

The Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio (official name: ''Basilica romana minore collegiata abbaziale prepositurale di Sant'Ambrogio'') is a church in the center of Milan, northern Italy.

History

One of the most ancient churches in Milan, it was built by ...

in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. The altars four sides are decorated with images in gold and silver repoussé, framed by borders of filigree

Filigree (also less commonly spelled ''filagree'', and formerly written ''filigrann'' or ''filigrene'') is a form of intricate metalwork used in jewellery and other small forms of metalwork.

In jewellery, it is usually of gold and silver, ma ...

, precious stones and enamel.

The Lothair Crystal

The Lothair Crystal (also known as the Lothar Crystal or the Susanna Crystal) is an engraved gem from Lotharingia in northwest Europe, showing scenes of the biblical story of Susanna, dating from 855–869. The Lothair Crystal is an object in t ...

, of the middle of the 9th century, is one of the largest of a group of about 20 engraved pieces of rock crystal

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

which survive; this shows large numbers of figures in several scenes showing the unusual subject of the story of Suzanna.

Mosaics and frescos

Sources attest to the abundance of wall paintings seen in churches and palaces, most of which have not survived. Records of inscriptions show that their subject matter was primarily religious.

Sources attest to the abundance of wall paintings seen in churches and palaces, most of which have not survived. Records of inscriptions show that their subject matter was primarily religious.

Mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s installed in Charlemagne's palatine chapel showed an enthroned Christ worshipped by the Evangelist's symbols and the twenty-four elders from the Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

. This mosaic no longer survives, but an over-restored one remains in the apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

of the oratory at Germigny-des-Prés

Germigny-des-Prés () is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France.

The Oratory

The oratory at Germigny-des-Prés (Loiret, Orléanais) was built by Bishop Theodulf of Orléans in 806 as part of his palace complex within the Gal ...

(806) which shows the Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant,; Ge'ez: also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, is an alleged artifact believed to be the most sacred relic of the Israelites, which is described as a wooden chest, covered in pure gold, with an e ...

adored by angels, discovered in 1820 under a coat of plaster.

The villa to which the oratory was attached belonged to a key associate of Charlemagne, Bishop Theodulf of Orléans

Theodulf of Orléans (Saragossa, Spain, 750(/60) – 18 December 821) was a writer, poet and the Bishop of Orléans (c. 798 to 818) during the reign of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. He was a key member of the Carolingian Renaissance and an im ...

. It was destroyed later in the century, but had fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

s of the Seven liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

, the Four Seasons, and the Mappa Mundi

A ''mappa mundi'' (Latin ; plural = ''mappae mundi''; french: mappemonde; enm, mappemond) is any medieval European map of the world. Such maps range in size and complexity from simple schematic maps or less across to elaborate wall maps, the ...

.Beckwith, 13–17 We know from written sources of other fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

s in churches and palaces, nearly all completely lost. Charlemagne's Aachen palace contained a wall painting of the Liberal Arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the ...

, as well as narrative scenes from his war in Spain. The palace of Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqui ...

at Ingelheim

Ingelheim (), officially Ingelheim am Rhein ( en, Ingelheim upon Rhine), is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district in the Rhineland-Palatinate state of Germany. The town sprawls along the Rhine's west bank. It has been Mainz-Bingen's district seat ...

contained historical images from antiquity to the time of Charlemagne, and the palace church contained typological scenes of the Old and New Testaments juxtaposed with one another.

Fragmentary paintings have survived at Auxerre

Auxerre ( , ) is the capital of the Yonne department and the fourth-largest city in Burgundy. Auxerre's population today is about 35,000; the urban area (''aire d'attraction'') comprises roughly 113,000 inhabitants. Residents of Auxerre are r ...

, Coblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its na ...

, Lorsch

Lorsch is a town in the Bergstraße district in Hessen, Germany, 60 km south of Frankfurt. Lorsch is well known for the Lorsch Abbey, which has been named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Geography

Location

Lorsch lies about 5 km wes ...

, Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a town in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the town hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

History ...

, Corvey

The Princely Abbey of Corvey (german: link=no, Fürststift Corvey or Fürstabtei Corvey) is a former Benedictine abbey and ecclesiastical principality now in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was one of the half-dozen self-ruling '' princely ...

, Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

, Müstair

Müstair is a village in the Val Müstair municipality in the district of Inn in the Swiss canton of Graubünden. In 2009 Müstair merged with Fuldera, Lü, Switzerland, Santa Maria Val Müstair, Tschierv and Valchava to form Val Müstair.

, Mals

Mals (; it, Malles Venosta ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in South Tyrol in northern Italy, located about northwest of Bolzano, on the border with Switzerland and Austria.

History

Coat-of-arms

The emblem is party per fess: the upper of gul ...

, Naturns

Naturns (; it, Naturno ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of South Tyrol in northern Italy, located about northwest of the city of Bolzano.

Geography

As of 31 December 2015, it had a population of 5,739 and an area of .All demogra ...

, Cividale

Cividale del Friuli ( fur, Cividât (locally ); german: Östrich; sl, Čedad) is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Udine, part of the Northern Italy, North-Italian Friuli Venezia Giulia ''regione''. The town lies above sea-level in the foo ...

, Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and ''comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo. ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

.

Spolia

''

''Spolia

''Spolia'' (Latin: 'spoils') is repurposed building stone for new construction or decorative sculpture reused in new monuments. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice whereby stone that has been quarried, cut and used in a built ...

'' is the Latin term for "spoils" and is used to refer to the taking or appropriation of ancient monumental or other art works for new uses or locations. We know that many marbles and columns were brought from Rome northward during this period.

Perhaps the most famous example of Carolingian spolia is the tale of an equestrian statue. In Rome, Charlemagne had seen the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

The ''Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius'' (, ) is an ancient Roman equestrian statue on the Capitoline Hill, Rome, Italy. It is made of bronze and stands 4.24 m (13.9 ft) tall. Although the emperor is mounted, it exhibits many similari ...

in the Lateran Palace

The Lateran Palace ( la, Palatium Lateranense), formally the Apostolic Palace of the Lateran ( la, Palatium Apostolicum Lateranense), is an ancient palace of the Roman Empire and later the main papal residence in southeast Rome.

Located on St. ...

. It was the only surviving statue of a pre-Christian Roman Emperor because it was mistakenly thought, at the time, to be that of Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

and thus held great accord—Charlemagne thus brought an equestrian statue from Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

, then believed to be that of Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy b ...

, to Aachen, to match the statue of "Constantine" in Rome.

Antique carved gems were reused in various settings, without much regard to their original iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

.

See also

*Carolingian architecture

Carolingian architecture is the style of north European Pre-Romanesque architecture belonging to the period of the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and 9th centuries, when the Carolingian dynasty dominated west European politics. It was ...

* Codex Vaticanus 3868

Notes

References

* Beckwith, John. ''Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque'', Thames & Hudson, 1964 (rev. 1969), * Dodwell, C.R.; ''The Pictorial Arts of the West, 800–1200'', 1993, Yale UP, * Gaehde, Joachim E. (1989). "Pre-Romanesque Art". ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages

The ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages'' is a 13-volume encyclopedia of the Middle Ages published by the American Council of Learned Societies between 1982 and 1989. It was first conceived and started in 1975 with American medieval historian Jo ...

''.

* Hinks, Roger. ''Carolingian Art'', 1974 edn. (1935 1st edn.), University of Michigan Press,

* Kitzinger, Ernst, ''Early Medieval Art at the British Museum'', (1940) 2nd edn, 1955, British Museum

* Lasko, Peter, ''Ars Sacra, 800-1200'', Penguin History of Art (now Yale), 1972 (nb, 1st edn.)

"Carolingian art"

In ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' Online

Further reading

* (see index)External links

* Ross, Nancy,Carolingian Art

',

Smarthistory

Smarthistory is a free resource for the study of art history created by art historians Beth Harris and Steven Zucker. Smarthistory is an independent not-for-profit organization and the official partner to Khan Academy for art history.

Smarthisto ...

, undated

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carolingian Art

Medieval art

German art

French art

art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

Art by period of creation

Netherlandish Medieval art