Carl Schurz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors,

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors,

''Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity From Its Foundation In 1852 To Its Fiftieth Anniversary''. p. 209

Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company. In response to the early events of the When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to

During the

During the  Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker,

Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker,

In 1866, Schurz moved to

In 1866, Schurz moved to

In 1868, he was elected to the

In 1868, he was elected to the

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him  During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to

Schurz is commemorated in numerous places around the United States:

*

Schurz is commemorated in numerous places around the United States:

*

File:Schurz Conspirators.jpg, Schurz and other anti-Grant "conspirators" – March 16, 1872

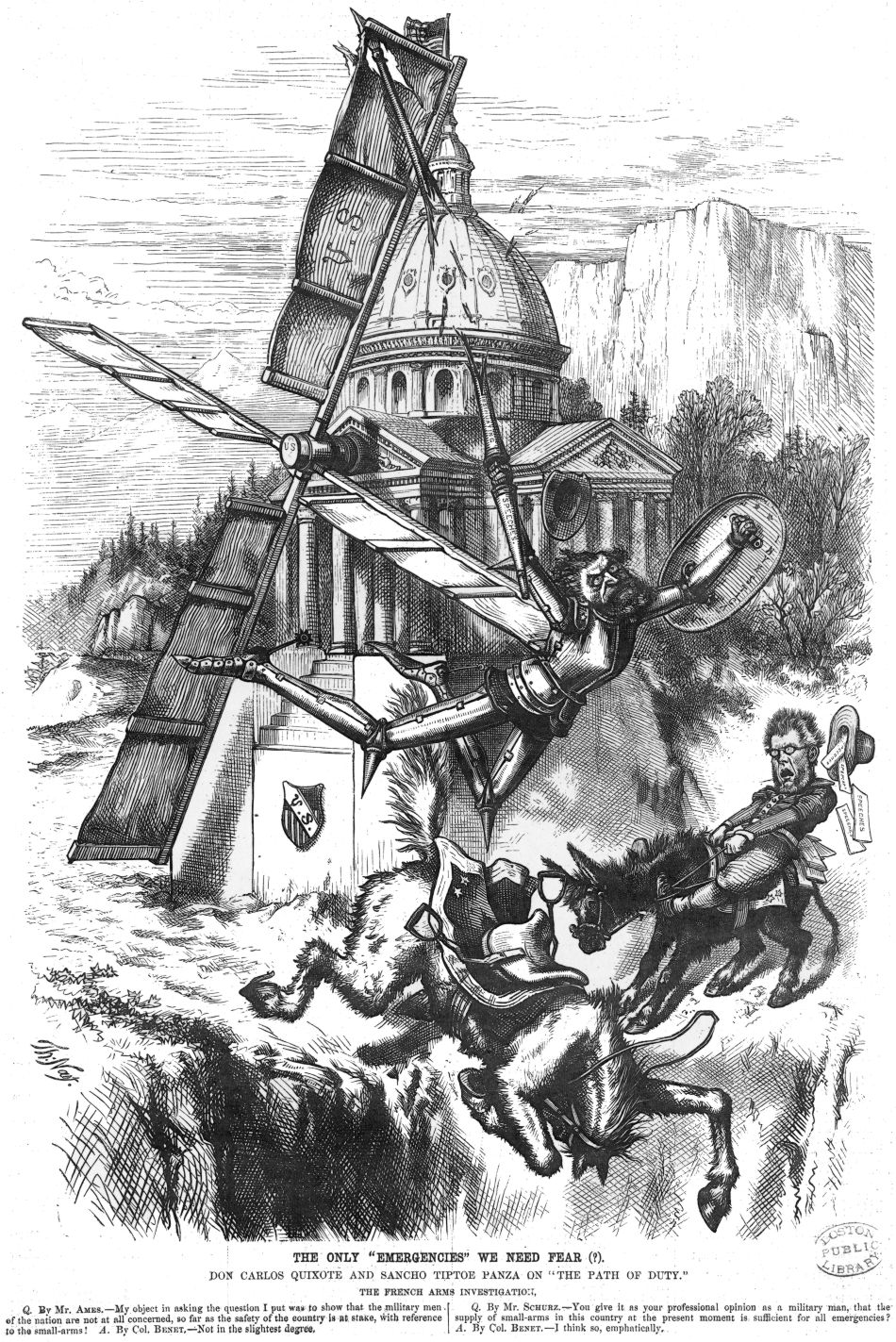

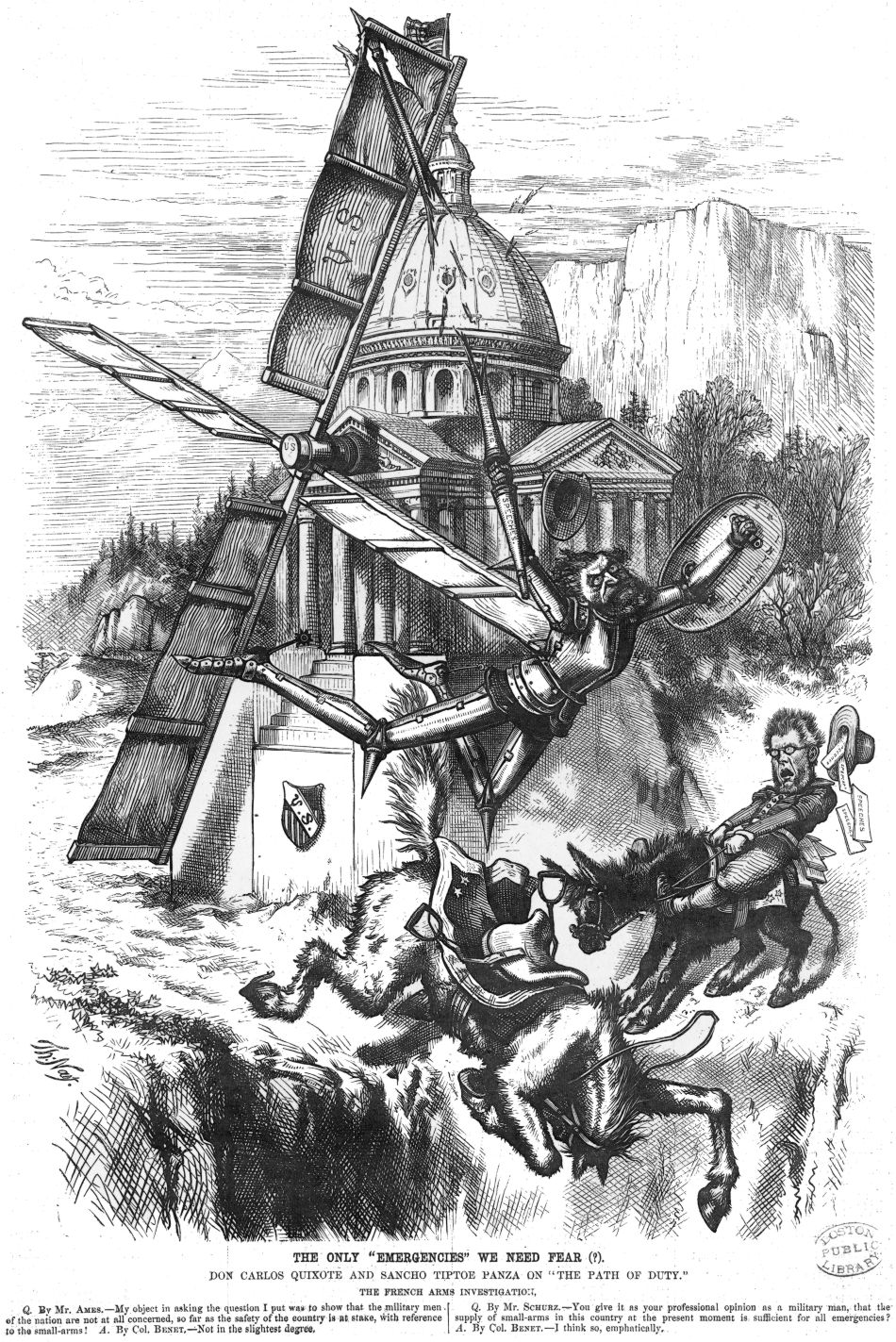

File:Schurz French Arms.png, French Arms investigation – May 11, 1872

File:Schurz Victims.jpg, Schurz and his victims – September 7, 1872

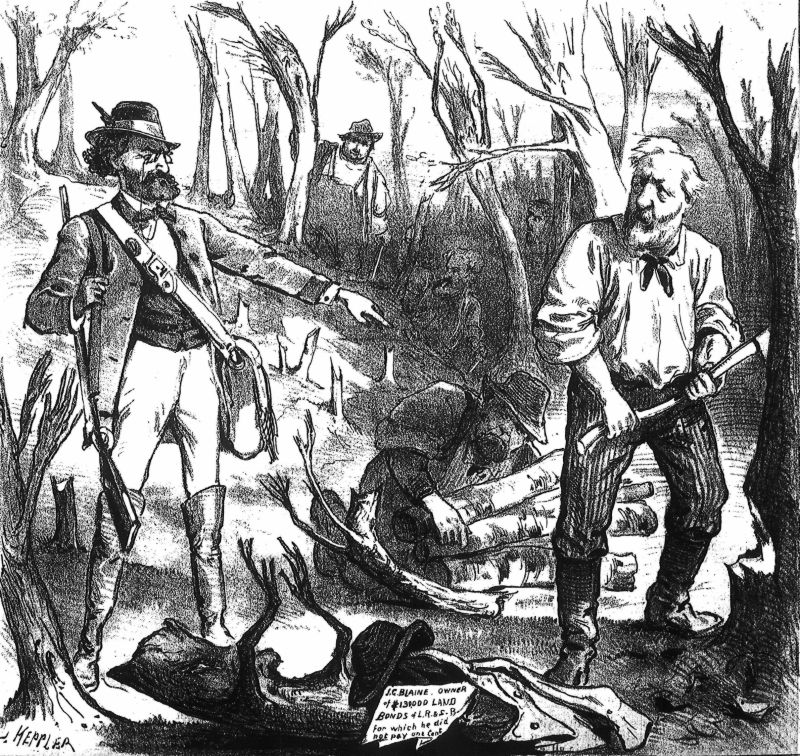

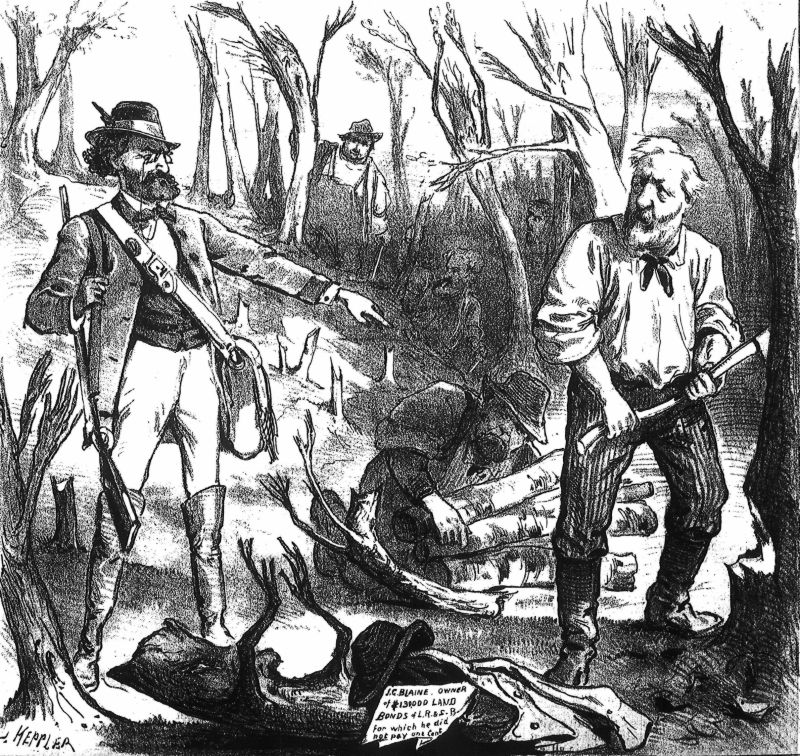

File:Carpetbagger.jpg, Schurz is depicted as a carpetbagger - November 9, 1872.

File:Schurz Senate Exit.jpg, Schurz leaves the U.S. Senate – March 20, 1875

File:Schurz Corruption.jpg, Schurz reforms the Indian Bureau – January 26, 1878

File:Schurz Have Patience With Indians.jpg, Schurz counsels a wounded settler – December 28, 1878

File:Schurz and Kaiser Wilhelm II.jpg, Schurz and

"Carl Schurz as Office Seeker,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 20, no.2 (December 1936), pp. 127–142. * Donner, Barbara

"Carl Schurz the Diplomat,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 20, no. 3 (March 1937), pp. 291–309. * Fish, Carl Russell

"Carl Schurz-The American,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 12, no. 4 (June 1929), pp. 346–368. * Fuess, Claude Moore ''Carl Schurz, Reformer'', (NY, Dodd Mead, 1932) * Nagel, Daniel. ''Von republikanischen Deutschen zu deutsch-amerikanischen Republikanern. Ein Beitrag zum Identitätswandel der deutschen Achtundvierziger in den Vereinigten Staaten 1850-1861.'' Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2012. * Schafer, Joseph

"Carl Schurz, Immigrant Statesman,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 11, no. 4 (June 1928), pp. 373–394. * Schurz, Carl

''Intimate Letters of Carl Schurz 1841-1869''

Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1928. * Trefousse, Hans L. ''Carl Schurz: A Biography'', (1st ed. Knoxville: U. of Tenn. Press, 1982; 2nd ed. New York: Fordham University Press, 1998) * Twain, Mark,

" ''Harper's Weekly'', May 26, 1906.

"A Man of Conscience"

''American Heritage Magazine'', vol. 14, no. 2 (1963).

"Schurz: The True Americanism"

''Harper's Magazine'', November 1, 2008.

from Charles Rounds, ''Wisconsin Authors and Their Works'', 1918.

Abraham Lincoln's White House - Carl Schurz

* Th

containing materials especially of interest to the examination of Schurz's image in the press and in the German-American community, are available for research use at the

Constitutional Minutes episode about Carl Schurz from the American Archive of Public Broadcasting

*

Constitutional Minutes- Series : Constitutional Minutes; Episode : Carl Schurz; Episode Number: 112

from American Archive of Public Broadcasting , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Schurz, Carl 1829 births 1906 deaths 19th-century American diplomats 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to Spain Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Civil service reform in the United States German American German-American Forty-Eighters German revolutionaries German emigrants to the United States Hayes administration cabinet members Liberal Republican Party United States senators Missouri Liberal Republicans Missouri Republicans People from Erftstadt People from the Rhine Province People of Missouri in the American Civil War People of the Revolutions of 1848 People of Wisconsin in the American Civil War Republican Party United States senators from Missouri Union Army generals United States Secretaries of the Interior University of Bonn alumni Wisconsin Republicans Writers from Missouri Writers from New York City Writers from Wisconsin

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

after the German revolutions of 1848–1849

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated pro ...

and became a prominent member of the new Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. After serving as a Union general in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, he helped found the short-lived Liberal Republican Party and became a prominent advocate of civil service reform. Schurz represented Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

and was the 13th United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natur ...

.

Born in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

's Rhine Province

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. ...

, Schurz fought for democratic reforms in the German revolutions of 1848–1849 as a member of the academic fraternity association Deutsche Burschenschaft. After Prussia suppressed the revolution Schurz fled to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. When police forced him to leave France he migrated to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. Like many other "Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human ...

", he then immigrated to the United States, settling in Watertown, Wisconsin

Watertown is a city in Dodge and Jefferson counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Most of the city's population is in Jefferson County. Division Street, several blocks north of downtown, marks the county line. The population of Watertown was 2 ...

, in 1852. After being admitted to the Wisconsin bar, he established a legal practice in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee i ...

. He also became a strong advocate for the anti-slavery movement and joined the newly organized Republican Party, unsuccessfully running for Lieutenant Governor of Wisconsin. After briefly representing the United States as Minister (ambassador) to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Schurz served as a general in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, fighting in the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

and other major battles.

After the war, Schurz established a newspaper in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, and won election to the U.S. Senate, becoming the first German-born American elected to that body. Breaking with Republican President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, Schurz helped establish the Liberal Republican Party. The party advocated civil service reform, sound money, low tariffs, low taxes, an end to railroad grants, and opposed Grant's efforts to protect African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

civil rights in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. Schurz chaired the 1872 Liberal Republican convention

An influential group of dissident Republicans split from the party to form the Liberal Republican Party in 1870. At the party's only national convention, held in Cincinnati in 1872, ''New York Tribune'' editor Horace Greeley was nominated for Pres ...

, which nominated a ticket that unsuccessfully challenged President Grant in the 1872 presidential election. Schurz lost his own 1874 re-election bid and resumed his career as a newspaper editor. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1878.

After Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

won the 1876 presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

, he appointed Schurz as his Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

. Schurz sought to make civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

based on merit rather than political and party connections and helped prevent the transfer of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

. Schurz moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

after Hayes left office in 1881 and briefly served as the editor of the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

'' and ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

'' and later became the editorial writer for ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

''. He remained active in politics and led the "Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

" movement, which opposed nominating James G. Blaine in the 1884 presidential election. Schurz opposed William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

's bimetallism in the 1896 presidential election but supported Bryan's anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

campaign in the 1900 presidential election. Schurz died in New York City in 1906.

Early life

Carl Christian Schurz was born on March 2, 1829, in Liblar (now part ofErftstadt

Erftstadt () is a town located about 20 km south-west of Cologne in the Rhein-Erft-Kreis, state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. The name of the town derives from the river that flows through it, the Erft. The neighbouring towns are Brüh ...

), in Rhenish Prussia

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. It ...

, the son of Marianne (née Jussen), a public speaker and journalist, and Christian Schurz, a schoolteacher. He studied at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

, and learned piano under private instructors. Financial problems in his family obligated him to leave school a year early, without graduating. Later he graduated from the gymnasium by passing a special examination and then entered the University of Bonn

The Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (german: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn) is a public research university located in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the ( en, Rhine ...

.''Dictionary Of American Biography'' (1935), ''Carl Schurz'', p. 466.

Revolution of 1848

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors,

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors, Gottfried Kinkel

Johann Gottfried Kinkel (11 August 1815 – 13 November 1882) was a German poet also noted for his revolutionary activities and his escape from a Prussian prison in Spandau with the help of his friend Carl Schurz.

Early life

He was born at Ober ...

. He joined the nationalistic Studentenverbindung

(; often referred to as Verbindung) is the umbrella term for many different kinds of fraternity-type associations in German-speaking countries, including Corps, , , , and Catholic fraternities. Worldwide, there are over 1,600 , about a thousan ...

Burschenschaft

A Burschenschaft (; sometimes abbreviated in the German ''Burschenschaft'' jargon; plural: ) is one of the traditional (student associations) of Germany, Austria, and Chile (the latter due to German cultural influence).

Burschenschaften were fo ...

Franconia at Bonn, which at the time included among its members Friedrich von Spielhagen, Johannes Overbeck, Julius Schmidt, Carl Otto Weber, Ludwig Meyer and Adolf Strodtmann.Van Cleve, Charles L. (1902)''Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity From Its Foundation In 1852 To Its Fiftieth Anniversary''. p. 209

Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company. In response to the early events of the

revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, Schurz and Kinkel founded the ''Bonner Zeitung'', a paper advocating democratic reforms. At first Kinkel was the editor and Schurz a regular contributor.

These roles were reversed when Kinkel left for Berlin to become a member of the Prussian Constitutional Convention. When the Frankfurt rump parliament called for people to take up arms in defense of the new German constitution, Schurz, Kinkel, and others from the University of Bonn community did so. During this struggle, Schurz became acquainted with Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

, Alexander Schimmelfennig, Fritz Anneke

Karl Friedrich Theodor "Fritz" Anneke () was a German revolutionary, socialist and newspaper editor. He emigrated to the United States with his family in 1849 and became a Union Army officer in the American Civil War, and later worked as an en ...

, Friedrich Beust, Ludwig Blenker

Louis Blenker (July 31, 1812 – October 31, 1863) was a German revolutionary and American soldier.

Life in Germany

He was born at Worms, Germany. After being trained as a goldsmith by an uncle in Kreuznach, he was sent to a polytechnical ...

and others, many of whom he would meet again in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War.

During the 1849 military campaign in Palatinate and Baden, he joined the revolutionary army, fighting in several battles against the Prussian Army. Schurz was adjunct officer of the commander of the artillery, Fritz Anneke

Karl Friedrich Theodor "Fritz" Anneke () was a German revolutionary, socialist and newspaper editor. He emigrated to the United States with his family in 1849 and became a Union Army officer in the American Civil War, and later worked as an en ...

, who was accompanied on the campaign by his wife, Mathilde Franziska Anneke

Mathilde Franziska Anneke (née Giesler; April 3, 1817 – November 25, 1884) was a German writer, feminist, and radical democrat who participated in the Revolutions of 1848–1849. In late 1849, she moved to the United States, where she campaign ...

. The Annekes would later move to the U.S., where each became Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

supporters. Anneke's brother, Emil Anneke

Emil Anneke (''Emil Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Annecke''; December 13, 1823 in Dortmund – October 27, 1888 in Bay City, Michigan, United States) was a German revolutionary and Forty-Eighter and American journalist, lawyer and politician (Republican ...

, was a founder of the Republican party in Michigan. Fritz Anneke achieved the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

and became the commanding officer of the 34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War; Mathilde Anneke contributed to both the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and suffrage movements of the United States.

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

. In 1850, he returned secretly to Prussia, rescued Kinkel from prison at Spandau

Spandau () is the westernmost of the 12 boroughs () of Berlin, situated at the confluence of the Havel and Spree rivers and extending along the western bank of the Havel. It is the smallest borough by population, but the fourth largest by land ...

and helped him to escape to Edinburgh, Scotland

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of ...

. Schurz then went to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, but the police forced him to leave France on the eve of the coup d'état of 1851, and he migrated to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. Remaining there until August 1852, he made his living by teaching the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is als ...

.

Immigration to America

While in London, Schurz married fellow revolutionaryJohannes Ronge

Johannes Ronge (16 October 1813 – 26 October 1887) was the principal founder of the New Catholics. A Roman Catholic priest from the region of Upper Silesia in Prussia, he was suspended from the priesthood for his criticisms of the church, and we ...

's sister-in-law, Margarethe Meyer, in July 1852 and then, like many other Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human ...

, immigrated to the United States. Living initially in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, the Schurzes moved to Watertown, Wisconsin

Watertown is a city in Dodge and Jefferson counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Most of the city's population is in Jefferson County. Division Street, several blocks north of downtown, marks the county line. The population of Watertown was 2 ...

, where Carl nurtured his interests in politics and Margarethe began her seminal work in early childhood education.

In Wisconsin, Schurz soon became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. In 1857, he ran unsuccessfully as a Republican for lieutenant governor. In the Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

campaign of the next year between Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Stephen A. Douglas, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln—mostly in German—which raised Lincoln's popularity among German-American voters. In 1858, Schurz was admitted to the Wisconsin bar and began to practice law in Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee ...

. Beginning 1859, his law partner was Halbert E. Paine. With Paine's encouragement, Schurz took more of an interest in politics and public speaking than in law. In the state campaign of 1859, Schurz made a speech attacking the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

, arguing for states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

. In Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall ( or ; previously ) is a marketplace and meeting hall located near the waterfront and today's Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts. Opened in 1742, it was the site of several speeches by Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others ...

, Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, on April 18, 1859, he delivered an oration on "True Americanism", which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of " nativism". Wisconsin Germans unsuccessfully urged his nomination for governor in 1859. In the 1860 Republican National Convention, Schurz was spokesman of the delegation from Wisconsin, which voted for William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

. Despite this, Schurz was on the committee which brought Lincoln the news of his nomination.

After Lincoln's election and in spite of Seward's objection, Lincoln sent Schurz as minister to Spain in 1861,''Dictionary Of American Biography'' (1935), ''Carl Schurz'', p. 467 in part because of Schurz's European record as a revolutionary. While there Schurz succeeded in quietly dissuading Spain from supporting the South.

American Civil War

During the

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Schurz served with distinction as a general in the Union Army. Persuading Lincoln to grant him a commission in the Union army, Schurz was commissioned brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of Union volunteers in April 1862. In June, he took command of a division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

, first under John C. Frémont, and then in Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

's corps, with which he took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. He was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

in 1863 and was assigned to lead a division in the XI Corps at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, both under General Oliver O. Howard. A bitter controversy began between Schurz and Howard over the strategy employed at Chancellorsville, resulting in the routing of the XI Corps by the Confederate corps led by Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Two months later, the XI Corps again broke during the first day of Gettysburg. Containing several German-American units, the XI Corps performance during both battles was heavily criticized by the press, fueling anti-immigrant sentiments.

Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker,

Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker, John Patterson Rea

John Patterson Rea (1840–1900) was a Minnesota judge. He was also editor of the ''Minneapolis Tribune'', and from late 1887 to 1888 Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, succeeding Lucius Fairchild.

Early life and ancestry

Re ...

, and Luther Morris Buchwalter, brother to Morris Lyon Buchwalter. Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

(R-MA) was a Congressional observer during the Chattanooga Campaign. Later, he was put in command of a Corps of Instruction at Nashville. He briefly returned to active service, where in the last months of the war he was with Sherman's army in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

as chief of staff of Henry Slocum's Army of Georgia

The Army of Georgia was a Union army that constituted the Left Wing of Major General William T. Sherman's Army Group during the March to the Sea and the Carolinas Campaign.

History

During Sherman's Atlanta Campaign in 1864, his Army Group wa ...

. He resigned from the army after the war ended in April 1865.

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Schurz through the South to study conditions. They then quarreled because Schurz supported General Slocum's order forbidding the organization of militia in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. Schurz delivered a report to the U.S. Senate documenting conditions in the South which concluded that Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

had succeeded in restoring the basic functioning of government but failed in restoring the loyalty of the people and protecting the rights of the newly legally emancipated who were still considered the slaves of society. It called for a national commitment to maintaining control over the South until free labor was secure, arguing that without national action, Black Codes and violence including numerous extrajudicial killings

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whether ...

documented by Schurz were likely to continue. The report was ignored by the President, but it helped fuel the movement pushing for a larger congressional role in Reconstruction and holding Southern states to higher standards.

Newspaper career

In 1866, Schurz moved to

In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, where he was chief editor of the '' Detroit Post''. The following year, he moved to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, becoming editor and joint proprietor with Emil Preetorius of the German-language '' Westliche Post'' (Western Post), where he hired Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867–1868, he traveled in Germany; his account of his interview with Otto von Bismarck is one of the most interesting chapters of his ''Reminiscences''. He spoke against "repudiation" of war debts and for "honest money"—code for going back on the gold standard—during the Presidential campaign of 1868.

U.S. Senator

In 1868, he was elected to the

In 1868, he was elected to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

from Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, becoming the first German American in that body. He earned a reputation for his speeches, which advocated fiscal responsibility, anti-imperialism, and integrity in government. During this period, he broke with the Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

administration, starting the Liberal Republican movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected B. Gratz Brown governor.

After William P. Fessenden's death, Schurz became a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs where Schurz opposed Grant's Southern policy as well as his bid to annex Santo Domingo. Schurz was identified with the committee's investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1869, he became the first U.S. Senator to offer a Civil Service Reform bill to Congress. During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Schurz was opposed to federal military enforcement and protection of African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

, and held nineteenth century ideas of European superiority and fears of miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

.Brands

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create an ...

(2012), ''The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace'', p. 489.

In 1870, Schurz helped form the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

's annexation of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

and his use of the military to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in the South under the Enforcement Acts.

In 1872, he presided over the Liberal Republican Party convention, which nominated Horace Greeley for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

. Schurz's own choice was Charles Francis Adams or Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull esta ...

, and the convention did not represent Schurz's views on the tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

. Schurz campaigned for Greeley anyway. Especially in this campaign, and throughout his career as a Senator and afterwards, he was a target for the pen of ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' artist Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a critic of Democratic Representative "Boss" Tweed and ...

, usually in an unfavorable way. The election was a debacle for the Greeley supporters. Grant won by a landslide, and Greeley died shortly after the election.

Schurz lost the 1874 Senatorial election to Democratic Party challenger and former Confederate Francis Cockrell. After leaving office, he worked as an editor for various newspapers. In 1875, he assisted in the successful campaign of Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

to regain the office of Governor of Ohio. In 1877, Schurz was appointed United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natur ...

by Hayes, who had been by then been elected President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. Although Schurz honestly attempted to reduce the effects of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

toward Native Americans and was partially successful at cleaning up corruption, his recommended actions towards American Indians "in light of late twentieth-century developments" were repressive. Fishel-Spragens (1988), ''Popular Images of American Presidents'', p. 121 Indians were forced to move into low-quality reservation lands that were unsuitable for tribal economic and cultural advancement. Promises made to Indian chiefs at White House meetings with President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

and Schurz were often broken.

Secretary of the Interior

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

, following much of his advice in other cabinet appointments and in his inaugural address. In this department, Schurz put into force his belief that merit should be the principal consideration in appointing civil servants to jobs in the Civil Service. He was not in favor of permitting removals except for cause, and supported requiring competitive examinations for candidates for clerkships. His efforts to remove political patronage met with only limited success, however. As an early conservationist, he prosecuted land thieves and attracted public attention to the necessity of forest preservation.

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

began, assisted by the strong support of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

. Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its "pacification" program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department. The Indian Office had been the most corrupt office in the Interior Department. Positions in it were based on political patronage and were seen as granting license to use the reservations for personal enrichment. Because Schurz realized that the service would have to be cleansed of such corruption before anything positive could be accomplished, he instituted a wide-scale inspection of the service, dismissed several officials, and began civil service reforms whereby positions and promotions were to be based on merit not political patronage.

Schurz's leadership of the Indian Affairs Office was at times controversial. While certainly not an architect of forced displacement of Native Americans, he continued the practice. In response to several nineteenth-century reformers, however, he later changed his mind and promoted an assimilationist policy.

Later life

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. That year German-born Henry Villard

Henry Villard (April 10, 1835 – November 12, 1900) was an American journalist and financier who was an early president of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Born and raised by Ferdinand Heinrich Gustav Hilgard in the Rhenish Palatinate of the Kin ...

, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, acquired the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

'' and ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

'' and turned the management over to Schurz, Horace White

Horace White (October 7, 1865 – November 27, 1943) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. He was the 37th Governor of New York from October 6, 1910 to December 31, 1910.

Life

He attended Syracuse Central High School, Cornell Un ...

and Edwin L. Godkin. Schurz left the ''Post'' in the autumn of 1883 because of differences over editorial policies regarding corporations and their employees.

In 1884, he was a leader in the Independent (or Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

) movement against the nomination of James Blaine for president and for the election of Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. From 1888 to 1892, he was general American representative of the Hamburg American Steamship Company

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

. In 1892, he succeeded George William Curtis

George William Curtis (February 24, 1824 – August 31, 1892) was an American writer and public speaker born in Providence, Rhode Island. An early Republican, he spoke in favor of African-American equality and civil rights both before and after ...

as president of the National Civil Service Reform League The National Civil Service Reform League was a non-profit organization in the United States founded in 1881 for the purpose of investigating the efficiency of the civil service. Among its founders were George William Curtis, chairman of the first ...

and held this office until 1901. He also succeeded Curtis as editorial writer for ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' in 1892 and held this position until 1898. In 1895 he spoke for the Fusion anti-Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

ticket in New York City. He opposed William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

for president in 1896, speaking for sound money and not under the auspices of the Republican party; he supported Bryan four years later because of anti-imperialism beliefs, which also led to his membership in the American Anti-Imperialist League

The American Anti-Imperialist League was an organization established on June 15, 1898, to battle the American annexation of the Philippines as an insular area. The anti-imperialists opposed forced expansion, believing that imperialism violated t ...

.

True to his anti-imperialist convictions, Schurz exhorted McKinley to resist the urge to annex land following the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

.Tucker (1998), p. 114. In the 1904 election he supported Alton B. Parker

Alton Brooks Parker (May 14, 1852 – May 10, 1926) was an American judge, best known as the Democrat who lost the presidential election of 1904 to Theodore Roosevelt.

A native of upstate New York, Parker practiced law in Kingston, New York, ...

, the Democratic candidate. Carl Schurz lived in a summer cottage in Northwest Bay on Lake George, New York which was built by his good friend Abraham Jacobi.

Death and legacy

Schurz died at age 77 on May 14, 1906, in New York City, and is buried inSleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch ...

, Sleepy Hollow, New York.

Schurz's wife, Margarethe Schurz, was instrumental in establishing the kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th ce ...

system in the United States.

Schurz is famous for saying: " My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right."

He was portrayed by Edward G. Robinson as a friend of the surviving Cheyenne Indians in John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

's 1964 film '' Cheyenne Autumn.''

Works

Schurz published a volume of speeches (1865), a two-volume biography of Henry Clay (1887), essays on Abraham Lincoln (1899) andCharles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

(posthumous, 1951), and his ''Reminiscences'' (posthumous, 1907–09). His later years were spent writing the memoirs recorded in his ''Reminiscences'' which he was not able to finish, reaching only the beginnings of his U.S. Senate career. Schurz was a member of the Literary Society of Washington

The Literary Society of Washington was formed in 1874 by a group of friends and associates who wished to meet regularly for "literary and artistic improvement and entertainment". - page 3 For more than 140 years, this literary society has convene ...

from 1879 to 1880.

Memorials

Carl Schurz Park

Carl Schurz Park is a public park in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, named for German-born Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz in 1910, at the edge of what was then the solidly German-American community of Yorkville ...

, a park in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, adjacent to Yorkville, Manhattan

Yorkville is a neighborhood in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City. Its southern boundary is East 72nd Street, its northern East 96th Street, its western Third Avenue, and its eastern the East River. Yorkville is among the city's m ...

, overlooking the waters of Hell Gate

Hell Gate is a narrow tidal strait in the East River in New York City. It separates Astoria, Queens, from Randall's and Wards Islands.

Etymology

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of the Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'' (it first appeared on ...

. Named for Schurz in 1910, it is the site of Gracie Mansion

Archibald Gracie Mansion (commonly called Gracie Mansion) is the official residence of the Mayor of New York City. Built in 1799, it is located in Carl Schurz Park, at East End Avenue and 88th Street in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan. ...

, the residence of the Mayor of New York

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

since 1942

* Karl Bitter

Karl Theodore Francis Bitter (December 6, 1867 – April 9, 1915) was an Austrian-born American sculptor best known for his architectural sculpture, memorials and residential work.

Life and career

The son of Carl and Henrietta Bitter, he was ...

's 1913 monument to Schurz ("Defender Of Liberty And A Friend Of Human Rights") outside Morningside Park, at Morningside Drive and 116th Street in New York City

* Karl Bitter

Karl Theodore Francis Bitter (December 6, 1867 – April 9, 1915) was an Austrian-born American sculptor best known for his architectural sculpture, memorials and residential work.

Life and career

The son of Carl and Henrietta Bitter, he was ...

's 1914 monument to Schurz ("Our Greatest German American") in Menominee Park, Oshkosh, Wisconsin

* Carl Schurz and Abraham Jacobi Memorial Park in Bolton Landing, New York

* Schurz, Nevada named after him

* Carl Schurz Drive, a residential street in the northern end of his former home of Watertown, Wisconsin

Watertown is a city in Dodge and Jefferson counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Most of the city's population is in Jefferson County. Division Street, several blocks north of downtown, marks the county line. The population of Watertown was 2 ...

* Schurz Elementary School, in Watertown, Wisconsin

Watertown is a city in Dodge and Jefferson counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Most of the city's population is in Jefferson County. Division Street, several blocks north of downtown, marks the county line. The population of Watertown was 2 ...

* ''Carl Schurz Park'', a private membership park in Stone Bank (Town of Merton), Wisconsin, on the shore of Moose Lake

* Carl Schurz Forest, a forested section of the Ice Age Trail

The Ice Age Trail is a National Scenic Trail stretching in the state of Wisconsin in the United States. The trail is administered by the National Park Service, and is constructed and maintained by private and public agencies including the Ice ...

near Monches, Wisconsin

* Carl Schurz High School, a historic landmark in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, built in 1910.

* Schurz Hall, a student residence at the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou, MU, or Missouri) is a public land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus University of Missouri System. MU was founded in ...

.

* Carl Schurz Elementary School in New Braunfels, Texas

New Braunfels ( ) is a city in Comal and Guadalupe counties in the U.S. state of Texas known for its German Texan heritage. It is the seat of Comal County. The city covers and had a population of 90,403 as of the 2020 Census. A suburb just nor ...

* Mount Schurz

Mount Schurz el. is a mountain peak in the Absaroka Range in Yellowstone National Park. Mount Schurz is the second highest peak in Yellowstone. The mountain was originally named Mount Doane by Henry D. Washburn during the Washburn–Langfor ...

, a mountain in eastern Yellowstone, north of Eagle Peak Eagle Peak is the name of 44 mountain peaks of the United States including:

*Eagle Peak (Alaska)

* Eagle Peak (Admiralty Island), in Alaska

* Eagle Peak (Washington), a summit in Mount Rainier National Park

*Eagle Peak (Mariposa County, California), ...

and south of Atkins Peak, named in 1885 by the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

, to honor Schurz's commitment to protecting Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowst ...

* In 1983, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 4-cent Great Americans series

The Great Americans series is a set of definitive stamps issued by the United States Postal Service, starting on December 27, 1980, with the 19¢ stamp depicting Sequoyah, and continuing through 1999, the final stamp being the 55¢ Justin S. Morr ...

postage stamp with his name and portrait

*

* The was commissioned in 1917 as a Patrol Gun Boat. Formerly the small unprotected cruiser of the German Imperial Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

, the ship had been taken over by the U.S. Navy when hostilities between Germany and the U.S. commenced, after having been interned in Honolulu in 1914. The ''Schurz'' sank after a collision on 21 June 1918 off Beaufort Inlet, Florida.

Several memorials in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

also commemorate the life and work of Schurz, including:

* Carl-Schurz Kaserne, in Bremerhaven

Bremerhaven (, , Low German: ''Bremerhoben'') is a city at the seaport of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, a state of the Federal Republic of Germany.

It forms a semi-enclave in the state of Lower Saxony and is located at the mouth of the Riv ...

, has been home to U.S. Army units for several decades, including elements of the 2nd Armored Division (Forward). Today it houses Army transportation units and some civilian commercial activities related to commercial shipping.

* Streets named after him in Berlin-Spandau

Spandau () is a locality (''Ortsteil'') of Berlin in the homonymous borough (''Bezirk'') of Spandau. The historic city is situated, for the most part, on the western banks of the Havel river. As of 2020 the estimated population of Spandau was 39, ...

, Bremen, Stuttgart, Erftstadt-Liblar, Giessen, Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

, Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the third-largest city of the German state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital of Stuttgart and Mannheim, and the 22nd-largest city in the nation, with 308,436 inhabitants. ...

, Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

, Neuss

Neuss (; spelled ''Neuß'' until 1968; li, Nüss ; la, Novaesium) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located on the west bank of the Rhine opposite Düsseldorf. Neuss is the largest city within the Rhein-Kreis Neuss district. It ...

, Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was a ...

, Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

, Pforzheim

Pforzheim () is a city of over 125,000 inhabitants in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, in the southwest of Germany.

It is known for its jewelry and watch-making industry, and as such has gained the nickname "Goldstadt" ("Golden City") ...

, Pirmasens

Pirmasens (; pfl, Bärmesens (also ''Bermesens'' or ''Bärmasens'')) is an independent town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, near the border with France. It was famous for the manufacture of shoes. The surrounding rural district was called ''Lan ...

, Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, Wuppertal

Wuppertal (; "''Wupper Dale''") is, with a population of approximately 355,000, the seventh-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as the 17th-largest city of Germany. It was founded in 1929 by the merger of the cities and tow ...

* Schools in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

, Bremen, Berlin-Spandau

Spandau () is a locality (''Ortsteil'') of Berlin in the homonymous borough (''Bezirk'') of Spandau. The historic city is situated, for the most part, on the western banks of the Havel river. As of 2020 the estimated population of Spandau was 39, ...

, Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

, Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was a ...

and his place of birth, Erftstadt-Liblar

* The Carl-Schurz-Haus Freiburg, in Freiburg im Breisgau is an innovative institute (formerly Amerika-Haus) fostering German-American cultural relations

* an urban area in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

* the Carl Schurz Bridge over the Neckar River

The Neckar () is a river in Germany, mainly flowing through the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, with a short section through Hesse. The Neckar is a major right tributary of the Rhine. Rising in the Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis near Schwenn ...

* a memorial fountain as well as the house where Lt. Schurz was billeted in 1849 in Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was a ...

* German Armed Forces barracks in Hardheim

* German federal stamps in 1952 and 1976

* Carl-Schurz-Medal awarded annually to one distinguished citizen of his home town.

''Harper's Weekly'' gallery

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

– July 14, 1900

File:Schurz Worships Aguinaldo.png, Schurz and Emilio Aguinaldo – August 9, 1902

File:Schurz Departing Interior Department.jpg, - February 26, 1881

See also

* List of foreign-born United States Cabinet members * List of American Civil War generals (Union) *Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human ...

* German Americans in the Civil War

* German American

* German-American Heritage Foundation of the USA

* List of United States senators born outside the United States

This is a list of United States senators born outside the United States. It includes senators born in foreign countries (whether to American or foreign parents). The list also includes senators born in territories outside the United States that wer ...

*

Notes

References

* Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, . * * * Yockelson, Mitchell, "Hirschhorn", ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, .Further reading

* Schurz, Carl. ''The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz'' (three volumes), New York: McClure Publ. Co., 1907–08. Schurz covered the years 1829–1870 in his ''Reminiscences''. He died in the midst of writing them. The third volume is rounded out with ''A Sketch of Carl Schurz's Political Career 1869–1906'' by Frederic Bancroft and William A. Dunning. Portions of these ''Reminiscences'' were serialized in ''McClure's Magazine'' about the time the books were published and included illustrations not found in the books. * Bancroft, Frederic, ed. ''Speeches, Correspondence, and Political Papers of Carl Schurz'' (six volumes), New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1913. * Brown, Dee, ''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,'' 1971 * Donner, Barbara"Carl Schurz as Office Seeker,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 20, no.2 (December 1936), pp. 127–142. * Donner, Barbara

"Carl Schurz the Diplomat,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 20, no. 3 (March 1937), pp. 291–309. * Fish, Carl Russell

"Carl Schurz-The American,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 12, no. 4 (June 1929), pp. 346–368. * Fuess, Claude Moore ''Carl Schurz, Reformer'', (NY, Dodd Mead, 1932) * Nagel, Daniel. ''Von republikanischen Deutschen zu deutsch-amerikanischen Republikanern. Ein Beitrag zum Identitätswandel der deutschen Achtundvierziger in den Vereinigten Staaten 1850-1861.'' Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2012. * Schafer, Joseph

"Carl Schurz, Immigrant Statesman,"

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', vol. 11, no. 4 (June 1928), pp. 373–394. * Schurz, Carl

''Intimate Letters of Carl Schurz 1841-1869''

Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1928. * Trefousse, Hans L. ''Carl Schurz: A Biography'', (1st ed. Knoxville: U. of Tenn. Press, 1982; 2nd ed. New York: Fordham University Press, 1998) * Twain, Mark,

" ''Harper's Weekly'', May 26, 1906.

External links

* * * * Retrieved on 2008-08-12 * * * Reynolds, Robert L"A Man of Conscience"

''American Heritage Magazine'', vol. 14, no. 2 (1963).

"Schurz: The True Americanism"

''Harper's Magazine'', November 1, 2008.

from Charles Rounds, ''Wisconsin Authors and Their Works'', 1918.

Abraham Lincoln's White House - Carl Schurz

* Th

containing materials especially of interest to the examination of Schurz's image in the press and in the German-American community, are available for research use at the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a long-established research facility, based in Philadelphia. It is a repository for millions of historic items ranging across rare books, scholarly monographs, family chronicles, maps, press reports and v ...

.

Constitutional Minutes episode about Carl Schurz from the American Archive of Public Broadcasting

*

Constitutional Minutes- Series : Constitutional Minutes; Episode : Carl Schurz; Episode Number: 112