Capital letter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Letter case is the distinction between the

Letter case is the distinction between the

There is more variation in the height of the minuscules, as some of them have parts higher ( ascenders) or lower (

There is more variation in the height of the minuscules, as some of them have parts higher ( ascenders) or lower (

A minority of writing systems use two separate cases. Such writing systems are called ''bicameral scripts''. Languages that use the

A minority of writing systems use two separate cases. Such writing systems are called ''bicameral scripts''. Languages that use the

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

; Sentence case

: "

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

; Sentence case

: "

A mixed-case style in which the first word of the sentence is capitalised, as well as proper nouns and other words as required by a more specific rule. This is generally equivalent to the baseline universal standard of formal English orthography. : In

A mixed-case style with all words capitalised, except for certain subsets (particularly articles and short prepositions and conjunctions) defined by rules that are not universally standardised. The standardisation is only at the level of house styles and individual style manuals. ; Start case (First letter of each word capitalized) : "The Quick Brown Fox Jumps Over The Lazy Dog"

''Start case'' or ''initial caps'' is a simplified variant of title case. In

A unicase style with capital letters only. This can be used in headings and special situations, such as for typographical emphasis in text made on a typewriter. With the advent of the

Similar in form to capital letters but roughly the size of a lower-case "x", small caps can be used instead of lower-case letters and combined with regular caps in a mixed-case fashion. This is a feature of certain fonts, such as Copperplate Gothic. According to various typographical traditions, the height of small caps can be equal to or slightly larger than the x-height of the typeface (the smaller variant is sometimes called ''petite caps'' and may also be mixed with the larger variant). Small caps can be used for acronyms, names, mathematical entities, computer commands in printed text, business or personal printed stationery letterheads, and other situations where a given phrase needs to be distinguished from the main text. ; All lowercase :"the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" :A unicase style with no capital letters. This is sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer languages, and in informal electronic communications such as

:A unicase style with no capital letters. This is sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer languages, and in informal electronic communications such as

In the International System of Units (SI), a letter usually has different meanings in upper and lower case when used as a unit symbol. Generally, unit symbols are written in lower case, but if the name of the unit is derived from a proper noun, the first letter of the symbol is capitalised. Nevertheless, the ''name'' of the unit, if spelled out, is always considered a common noun and written accordingly in lower case. For example:

* 1 s (one second) when used for the base unit of

In the International System of Units (SI), a letter usually has different meanings in upper and lower case when used as a unit symbol. Generally, unit symbols are written in lower case, but if the name of the unit is derived from a proper noun, the first letter of the symbol is capitalised. Nevertheless, the ''name'' of the unit, if spelled out, is always considered a common noun and written accordingly in lower case. For example:

* 1 s (one second) when used for the base unit of

Spaces and

Punctuation is removed and spaces are replaced by single

Similar to snake case, above, except

Mixed case with no semantic or syntactic significance to the use of the capitals. Sometimes only

UpperA$ = UCASE$("a")

LowerA$ = LCASE$("A")

C and

char upperA = toupper('a');

char lowerA = tolower('A');

Case conversion is different with different

#define toupper(c) (islower(c) ? (c) – 'a' + 'A' : (c))

#define tolower(c) (isupper(c) ? (c) – 'A' + 'a' : (c))

This only works because the letters of upper and lower cases are spaced out equally. In ASCII they are consecutive, whereas with EBCDIC they are not; nonetheless the upper-case letters are arranged in the same pattern and with the same gaps as are the lower-case letters, so the technique still works.

Some computer programming languages offer facilities for converting text to a form in which all words are capitalised.

letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alphabe ...

that are in larger uppercase or capitals (or more formally ''majuscule'') and smaller lowercase (or more formally ''minuscule'') in the written representation of certain language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

s. The writing system

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable fo ...

s that distinguish between the upper and lowercase have two parallel sets of letters, with each letter in one set usually having an equivalent in the other set. The two case variants are alternative representations of the same letter: they have the same name and pronunciation

Pronunciation is the way in which a word or a language is spoken. This may refer to generally agreed-upon sequences of sounds used in speaking a given word or language in a specific dialect ("correct pronunciation") or simply the way a particular ...

and are treated identically when sorting in alphabetical order

Alphabetical order is a system whereby character strings are placed in order based on the position of the characters in the conventional ordering of an alphabet. It is one of the methods of collation. In mathematics, a lexicographical order is t ...

.

Letter case is generally applied in a mixed-case fashion, with both upper and lowercase letters appearing in a given piece of text for legibility. The choice of case is often prescribed by the grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

of a language or by the conventions of a particular discipline. In orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and ...

, the uppercase is primarily reserved for special purposes, such as the first letter of a sentence or of a proper noun

A proper noun is a noun that identifies a single entity and is used to refer to that entity (''Africa'', ''Jupiter'', '' Sarah'', ''Microsoft)'' as distinguished from a common noun, which is a noun that refers to a class of entities (''continent, ...

(called capitalisation, or capitalised words), which makes the lowercase the more common variant in regular text.

In some contexts (e.g. academical), it is conventional to use one case only. For example, engineering design drawings are typically labelled entirely in uppercase letters, which are easier to distinguish individually than the lowercase when space restrictions require that the lettering be very small. In mathematics, on the other hand, letter case may indicate the relationship between mathematical object

A mathematical object is an abstract concept arising in mathematics.

In the usual language of mathematics, an ''object'' is anything that has been (or could be) formally defined, and with which one may do deductive reasoning and mathematical p ...

s, with uppercase letters often representing “superior” objects (e.g., ''X'' could be a mathematical set containing the generic member ''x'').

Terminology

The terms ''upper case'' and ''lower case'' may be written as two consecutive words, connected with a hyphen (''upper-case'' and ''lower-case''particularly if they pre-modify another noun), or as a single word (''uppercase'' and ''lowercase''). These terms originated from the common layouts of the shallow drawers called ''type case

A type case is a compartmentalized wooden box used to store movable type used in letterpress printing

Letterpress printing is a technique of relief printing. Using a printing press, the process allows many copies to be produced by repeate ...

s'' used to hold the movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

for letterpress printing

Letterpress printing is a technique of relief printing. Using a printing press, the process allows many copies to be produced by repeated direct impression of an inked, raised surface against sheets or a continuous roll of paper. A worker com ...

. Traditionally, the capital letters were stored in a separate shallow tray or "case" that was located above the case that held the small letters.

''Majuscule'' (, less commonly ), for palaeographers, is technically any script whose letters have very few or very short ascenders and descenders, or none at all (for example, the majuscule scripts used in the Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, or the Book of Kells). By virtue of their visual impact, this made the term majuscule an apt descriptor for what much later came to be more commonly referred to as uppercase letters.

''Minuscule'' refers to lower-case letters. The word is often spelled ''miniscule'', by association with the unrelated word ''miniature'' and the prefix ''mini-''. This has traditionally been regarded as a spelling mistake (since ''minuscule'' is derived from the word ''minus''), but is now so common that some dictionaries tend to accept it as a nonstandard or variant spelling. ''Miniscule'' is still less likely, however, to be used in reference to lower-case letters.

Typographical considerations

The glyphs of lowercase letters can resemble smaller forms of the uppercase glyphs restricted to the base band (e.g. "C/c" and "S/s", cf. small caps) or can look hardly related (e.g. "D/d" and "G/g"). Here is a comparison of the upper and lower case variants of each letter included in theEnglish alphabet

The alphabet for Modern English is a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, each having an upper- and lower-case form. The word ''alphabet'' is a compound of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, ''alpha'' and '' beta''. ...

(the exact representation will vary according to the typeface

A typeface (or font family) is the design of lettering that can include variations in size, weight (e.g. bold), slope (e.g. italic), width (e.g. condensed), and so on. Each of these variations of the typeface is a font.

There are thousands o ...

and font used):

(Some lowercase letters have variations e.g. a/ɑ)

Typographically, the basic difference between the majuscules and minuscules is not that the majuscules are big and minuscules small, but that the majuscules generally have the same height (although, depending on the typeface, there may be some exceptions, particularly with ''Q'' and sometimes ''J'' having a descending element; also, various diacritic

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacriti ...

s can add to the normal height of a letter).

descender

In typography and handwriting, a descender is the portion of a letter that extends below the baseline of a font.

For example, in the letter ''y'', the descender is the "tail", or that portion of the diagonal line which lies below the ''v'' c ...

s) than the typical size. Normally, ''b, d, f, h, k, l, t '' are the letters with ascenders, and ''g, j, p, q, y'' are the ones with descenders. In addition, with old-style numerals still used by some traditional or classical fonts, ''6'' and ''8'' make up the ascender set, and ''3, 4, 5, 7'' and ''9'' the descender set.

Bicameral script

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, Cyrillic, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Coptic, Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

, Adlam, Warang Citi

Warang Citi (also written Varang Kshiti or Barang Kshiti; , IPA: /wɐrɐŋ ʧɪt̪ɪ/) is a writing system invented by Lako Bodra for the Ho language spoken in East India. It is used in primary and adult education and in various publications.

I ...

, Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, Garay, Zaghawa, and Osage scripts use letter cases in their written form as an aid to clarity. Another bicameral script, which is not used for any modern languages, is Deseret. The Georgian alphabet has several variants, and there were attempts to use them as different cases, but the modern written Georgian language does not distinguish case.

All other writing systems make no distinction between majuscules and minuscules a system called unicameral script or unicase

A unicase or unicameral alphabet has just one case for its letters. Arabic, Brahmic scripts like Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, Old Hungarian (Hungarian Runic), Hebrew, Iberian, Georgian, and Hangul are unicase writing systems, while (mod ...

. This includes most syllabic

Syllabic may refer to:

*Syllable, a unit of speech sound, considered the building block of words

**Syllabic consonant, a consonant that forms the nucleus of a syllable

*Syllabary, writing system using symbols for syllables

*Abugida, writing system ...

and other non-alphabetic scripts.

In scripts with a case distinction, lower case is generally used for the majority of text; capitals are used for capitalisation and emphasis when bold is not available. Acronym

An acronym is a word or name formed from the initial components of a longer name or phrase. Acronyms are usually formed from the initial letters of words, as in ''NATO'' (''North Atlantic Treaty Organization''), but sometimes use syllables, as ...

s (and particularly initialisms) are often written in all-caps, depending on various factors.

Capitalisation

Capitalisation is thewriting

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

Writing systems do not themselves constitute h ...

of a word

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible. Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no conse ...

with its first letter

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alphabe ...

in uppercase and the remaining letters in lowercase. Capitalisation rules vary by language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

and are often quite complex, but in most modern languages that have capitalisation, the first word of every sentence is capitalised, as are all proper noun

A proper noun is a noun that identifies a single entity and is used to refer to that entity (''Africa'', ''Jupiter'', '' Sarah'', ''Microsoft)'' as distinguished from a common noun, which is a noun that refers to a class of entities (''continent, ...

s.

Capitalisation in English, in terms of the general orthographic rules independent of context (e.g. title vs. heading vs. text), is universally standardised for formal writing. Capital letters are used as the first letter of a sentence, a proper noun, or a proper adjective. The names of the days of the week

In many languages, the names given to the seven days of the week are derived from the names of the classical planets in Hellenistic astronomy, which were in turn named after contemporary deities, a system introduced by the Sumerians and lat ...

and the names of the months are also capitalised, as are the first-person pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun (abbreviated ) is a word or a group of words that one may substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the parts of speech, but some modern theorists would not c ...

"I" and the vocative particle " O". There are a few pairs of words of different meanings whose only difference is capitalisation of the first letter. Honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

s and personal title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

s showing rank or prestige are capitalised when used together with the name of the person (for example, "Mr. Smith", "Bishop O'Brien", "Professor Moore") or as a direct address, but normally not when used alone and in a more general sense. It can also be seen as customary to capitalise any word in some contexts even a pronoun referring to the deity of a monotheistic religion.

Other words normally start with a lower-case letter. There are, however, situations where further capitalisation may be used to give added emphasis, for example in headings and publication titles (see below). In some traditional forms of poetry, capitalisation has conventionally been used as a marker to indicate the beginning of a line of verse independent of any grammatical feature. In political writing, parody and satire, the unexpected emphasis afforded by otherwise ill-advised capitalisation is often used to great stylistic effect, such as in the case of George Orwell's Big Brother.

Other languages vary in their use of capitals. For example, in German all nouns are capitalised (this was previously common in English as well, mainly in the 17th and 18th centuries), while in Romance

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

and most other European languages the names of the days of the week, the names of the months, and adjectives of nationality, religion, and so on normally begin with a lower-case letter. On the other hand, in some languages it is customary to capitalise formal polite pronouns, for example ''De'', ''Dem'' ( Danish), ''Sie'', ''Ihnen'' (German), and ''Vd'' or ''Ud'' (short for ''usted'' in Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

).

Informal communication, such as texting, instant messaging

Instant messaging (IM) technology is a type of online chat allowing real-time text transmission over the Internet or another computer network. Messages are typically transmitted between two or more parties, when each user inputs text and trigge ...

or a handwritten sticky note, may not bother to follow the conventions concerning capitalisation, but that is because its users usually do not expect it to be formal.

Exceptional letters and digraphs

* The German letter " ß" formerly existed only in lower case. The orthographical capitalisation does not concern "ß", which generally does not occur at the beginning of a word, and in the all-caps style it has traditionally been replaced by the digraph "SS". Since June 2017, however,capital ẞ

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

is accepted as an alternative in the all-caps style.

* The Greek upper-case letter " Σ" has two different lower-case forms: "ς" in word-final position and "σ" elsewhere. In a similar manner, the Latin upper-case letter " S" used to have two different lower-case forms: "s" in word-final position and " ſ " elsewhere. The latter form, called the long s

The long s , also known as the medial s or initial s, is an archaic form of the lowercase letter . It replaced the single ''s'', or one or both of the letters ''s'' in a 'double ''s sequence (e.g., "ſinfulneſs" for "sinfulness" and "poſ ...

, fell out of general use before the middle of the 19th century, except for the countries that continued to use blackletter typefaces such as Fraktur. When blackletter type fell out of general use in the mid-20th century, even those countries dropped the long s.

* The treatment of the Greek iota subscript

The iota subscript is a diacritic mark in the Greek alphabet shaped like a small vertical stroke or miniature iota placed below the letter. It can occur with the vowel letters eta , omega , and alpha . It represents the former presence of an o ...

with upper-case letters is complicated.

* Unlike most languages that use Latin-script and link the dotless upper-case " I" with the dotted lower-case "i", Turkish as well as some forms of Azeri have both a dotted and dotless I

I, or ı, called dotless I, is a letter used in the Latin-script alphabets of Azerbaijani, Crimean Tatar, Gagauz, Kazakh, Tatar, Kyrgyz, and Turkish. It commonly represents the close back unrounded vowel , except in Kazakh where it represen ...

, each in both upper and lower case. Each of the two pairs ("İ/i" and "I/ı") represents a distinctive phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

.

* In some languages, specific digraphs may be regarded as single letters, and in Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, the digraph " IJ/ij" is even capitalised with both components written in uppercase (for example, "IJsland" rather than "Ijsland"). In other languages, such as Welsh and Hungarian, various digraphs are regarded as single letters for collation purposes, but the second component of the digraph will still be written in lower case even if the first component is capitalised. Similarly, in South Slavic languages whose orthography is coordinated between the Cyrillic and Latin scripts, the Latin digraphs " Lj/lj", " Nj/nj" and " Dž/dž" are each regarded as a single letter (like their Cyrillic equivalents " Љ/љ", " Њ/њ" and " Џ/џ", respectively), but only in all-caps style should both components be in upper case (e.g. Ljiljan–LJILJAN, Njonja–NJONJA, Džidža–DŽIDŽA). Unicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, wh ...

designates a single character for each case variant (i.e., upper case, title case and lower case) of the three digraphs.

* Some English surnames such as fforbes are traditionally spelt with a digraph instead of a capital letter (at least for ff). This indicates a long and prestigious family tradition.

* In the Hawaiian orthography, the okina is a phonemic

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-west ...

symbol that visually resembles a left single quotation mark. Representing the glottal stop, the okina can be characterised as either a letter or a diacritic

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacriti ...

. As a unicase letter, the okina is unaffected by capitalisation; it is the following letter that is capitalised instead. According to the Unicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, wh ...

standard, the okina is formally encoded as , but it is not uncommon to substitute this with a similar punctuation

Punctuation (or sometimes interpunction) is the use of spacing, conventional signs (called punctuation marks), and certain typographical devices as aids to the understanding and correct reading of written text, whether read silently or aloud. An ...

character, such as the left single quotation mark or an apostrophe.

Related phenomena

Similar orthographic and graphostylistic conventions are used for emphasis or following language-specific or other rules, including: * Font effects such asitalic type

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right. Italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed ...

or oblique type

Oblique type is a form of type that slants slightly to the right, used for the same purposes as italic type. Unlike italic type, however, it does not use different glyph shapes; it uses the same glyphs as roman type, except slanted. Oblique and it ...

, boldface

In typography, emphasis is the strengthening of words in a text with a font in a different style from the rest of the text, to highlight them. It is the equivalent of prosody stress in speech.

Methods and use

The most common methods in W ...

, and choice of serif vs. sans-serif.

* Typographical conventions in mathematical formulae

Typographical conventions in mathematical formulae provide uniformity across mathematical texts and help the readers of those texts to grasp new concepts quickly.

Mathematical notation includes letters from various alphabets, as well as special ma ...

include the use of Greek letters and the use of Latin letters with special formatting such as blackboard bold

Blackboard bold is a typeface style that is often used for certain symbols in mathematical texts, in which certain lines of the symbol (usually vertical or near-vertical lines) are doubled. The symbols usually denote number sets. One way of pro ...

and blackletter.

* Some letters of the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and Hebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet ( he, אָלֶף־בֵּית עִבְרִי, ), known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewi ...

s and some jamo of the Korean hangul

The Korean alphabet, known as Hangul, . Hangul may also be written as following South Korea's standard Romanization. ( ) in South Korea and Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea, is the modern official writing system for the Korean language. The le ...

have different forms depending on placement within a word, but these rules are strict and the different forms cannot be used for emphasis.

**In the Arabic and Arabic-based alphabets, letters in a word are connected, except for several that cannot connect to the following letter. Letters may have distinct forms depending on whether they are initial (connected only to the following letter), medial (connected to both neighboring letters), final (connected only to the preceding letter), or isolated (connected to neither a preceding nor a following letter).

**In the Hebrew alphabet, five letters have a distinct form (see Final form) that is used when they are word-final.

* In Georgian, some authors use isolated letters from the ancient Asomtavruli alphabet within a text otherwise written in the modern Mkhedruli

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written hor ...

in a fashion that is reminiscent of the usage of upper-case letters in the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets.

* In the Japanese writing system

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese ...

, an author has the option of switching between kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese family of scripts, Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese language, Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese ...

, hiragana

is a Japanese syllabary, part of the Japanese writing system, along with ''katakana'' as well as ''kanji''.

It is a phonetic lettering system. The word ''hiragana'' literally means "flowing" or "simple" kana ("simple" originally as contrast ...

, katakana

is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji and in some cases the Latin script (known as rōmaji). The word ''katakana'' means "fragmentary kana", as the katakana characters are derived f ...

, and rōmaji

The romanization of Japanese is the use of Latin script to write the Japanese language. This method of writing is sometimes referred to in Japanese as .

Japanese is normally written in a combination of logographic characters borrowed from Ch ...

. In particular, every hiragana character has an equivalent katakana character, and vice versa. Romanised Japanese sometimes uses lowercase letters to represent words that would be written in hiragana, and uppercase letters to represent words that would be written in katakana. Some kana characters are written in smaller type when they modify or combine with the preceding sign (''yōon

The , also written as ''yōon'', is a feature of the Japanese language in which a mora is formed with an added sound, i.e., palatalized, or (more rarely in the modern language) with an added sound, i.e. labialized.

''Yōon'' are represented i ...

'') or the following sign (''sokuon

The is a Japanese symbol in the form of a small hiragana or katakana '' tsu''. In less formal language it is called or , meaning "small ''tsu''". It serves multiple purposes in Japanese writing.

Appearance

In both hiragana and katakana, ...

'').

Stylistic or specialised usage

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

; Sentence case

: "

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

; Sentence case

: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

"The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" is an English-language pangram — a sentence that contains all the letters of the alphabet. The phrase is commonly used for touch-typing practice, testing typewriters and computer keyboards, displ ...

"A mixed-case style in which the first word of the sentence is capitalised, as well as proper nouns and other words as required by a more specific rule. This is generally equivalent to the baseline universal standard of formal English orthography. : In

computer programming

Computer programming is the process of performing a particular computation (or more generally, accomplishing a specific computing result), usually by designing and building an executable computer program. Programming involves tasks such as anal ...

, the initial capital is easier to automate than the other rules. For example, on English-language Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a multilingual free online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers, known as Wikipedians, through open collaboration and using a wiki-based editing system. Wikipedia is the largest and most-read refer ...

, the first character in page titles is capitalised by default. Because the other rules are more complex, substring

In formal language theory and computer science, a substring is a contiguous sequence of characters within a string. For instance, "''the best of''" is a substring of "''It was the best of times''". In contrast, "''Itwastimes''" is a subsequenc ...

s for concatenation into sentences are commonly written in "mid-sentence case", applying all the rules of sentence case except the initial capital.

; Title case

Title case or headline case is a style of capitalization used for rendering the titles of published works or works of art in English. When using title case, all words are capitalized, except for minor words (typically articles, short prepositions, ...

(capital case, headline style)

: "The Quick Brown Fox Jumps over the Lazy Dog"A mixed-case style with all words capitalised, except for certain subsets (particularly articles and short prepositions and conjunctions) defined by rules that are not universally standardised. The standardisation is only at the level of house styles and individual style manuals. ; Start case (First letter of each word capitalized) : "The Quick Brown Fox Jumps Over The Lazy Dog"

''Start case'' or ''initial caps'' is a simplified variant of title case. In

text processing

In computing, the term text processing refers to the theory and practice of automating the creation or manipulation of electronic text.

''Text'' usually refers to all the alphanumeric characters specified on the keyboard of the person engaging t ...

, title case usually involves the capitalisation of all words irrespective of their part of speech

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class or grammatical category) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are as ...

.

; All caps

In typography, all caps (short for "all capitals") refers to text or a font in which all letters are capital letters, for example: "THIS TEXT IS IN ALL CAPS". All caps may be used for emphasis (for a word or phrase). They are commonly seen in l ...

(all uppercase)

: "THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG"A unicase style with capital letters only. This can be used in headings and special situations, such as for typographical emphasis in text made on a typewriter. With the advent of the

Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

, the all-caps style is more often used for emphasis; however, it is considered poor netiquette

Etiquette in technology, colloquially referred to as netiquette is a term used to refer to the unofficial code of policies that encourage good behavior on the Internet which is used to regulate respect and polite behavior on social media platforms ...

by some to type in all capitals, and said to be tantamount to shouting.RFC 1855 "Netiquette Guidelines" Long spans of Latin-alphabet text in all upper-case are more difficult to read because of the absence of the ascenders and descender

In typography and handwriting, a descender is the portion of a letter that extends below the baseline of a font.

For example, in the letter ''y'', the descender is the "tail", or that portion of the diagonal line which lies below the ''v'' c ...

s found in lower-case letters, which aids recognition and legibility. In some cultures it is common to write family names in all caps to distinguish them from the given names, especially in identity documents such as passports.

; Small caps

: ""Similar in form to capital letters but roughly the size of a lower-case "x", small caps can be used instead of lower-case letters and combined with regular caps in a mixed-case fashion. This is a feature of certain fonts, such as Copperplate Gothic. According to various typographical traditions, the height of small caps can be equal to or slightly larger than the x-height of the typeface (the smaller variant is sometimes called ''petite caps'' and may also be mixed with the larger variant). Small caps can be used for acronyms, names, mathematical entities, computer commands in printed text, business or personal printed stationery letterheads, and other situations where a given phrase needs to be distinguished from the main text. ; All lowercase :"the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

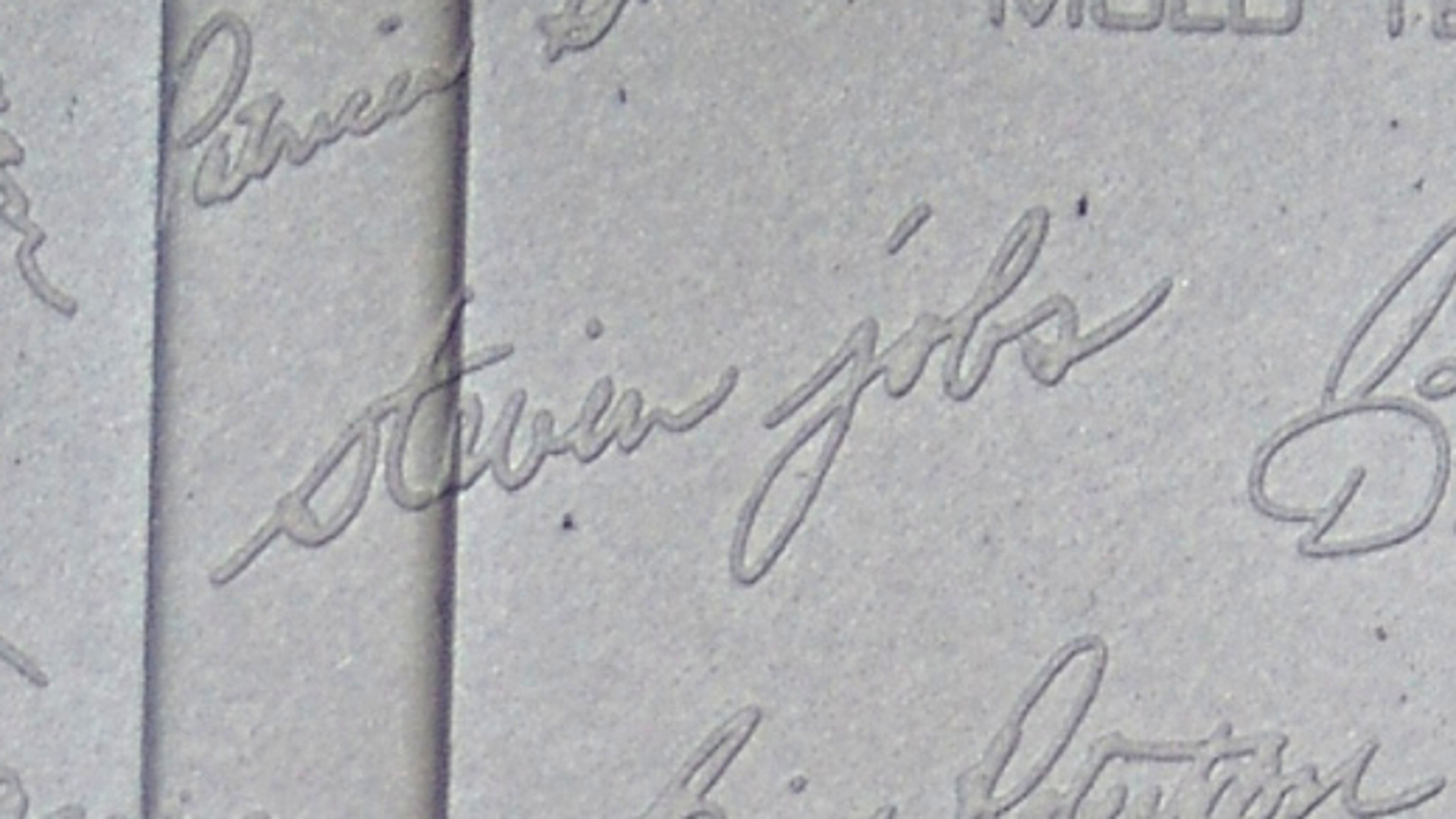

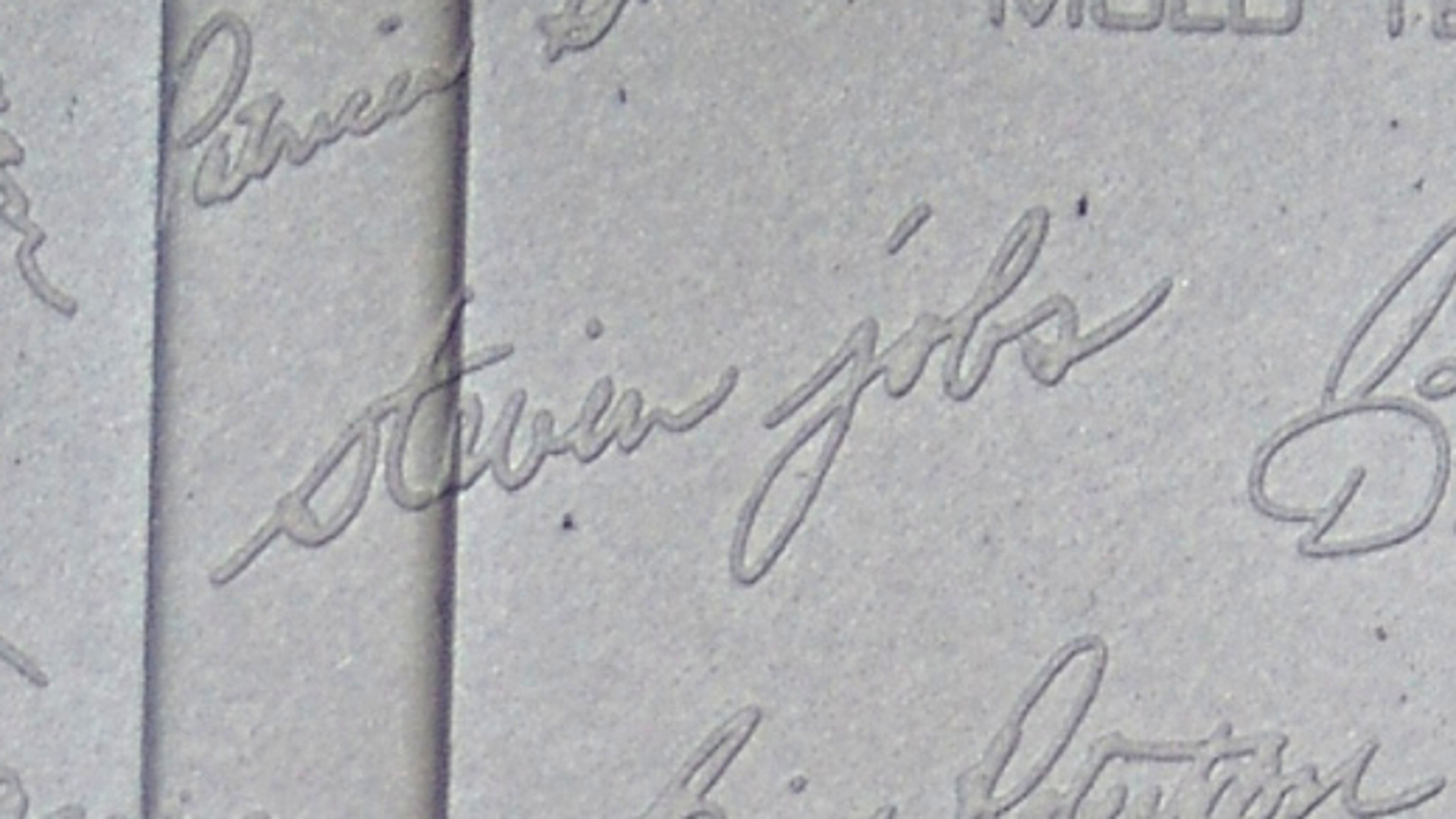

:A unicase style with no capital letters. This is sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer languages, and in informal electronic communications such as

:A unicase style with no capital letters. This is sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer languages, and in informal electronic communications such as SMS language

Short Message Service (SMS) language, textism, or textese is the abbreviated language and slang commonly used in the late 1990s and early 2000s with mobile phone text messaging, and occasionally through Internet-based communication such as ema ...

and instant messaging

Instant messaging (IM) technology is a type of online chat allowing real-time text transmission over the Internet or another computer network. Messages are typically transmitted between two or more parties, when each user inputs text and trigge ...

(avoiding the shift key

The Shift key is a modifier key on a keyboard, used to type capital letters and other alternate "upper" characters. There are typically two shift keys, on the left and right sides of the row below the home row. The Shift key's name originated f ...

, to type more quickly). Apple co-founder Steve Jobs used all-lowercase (in cursive) in his signature.

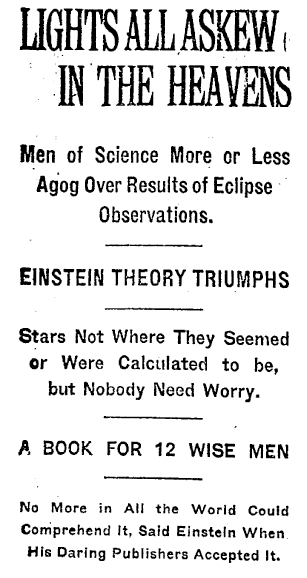

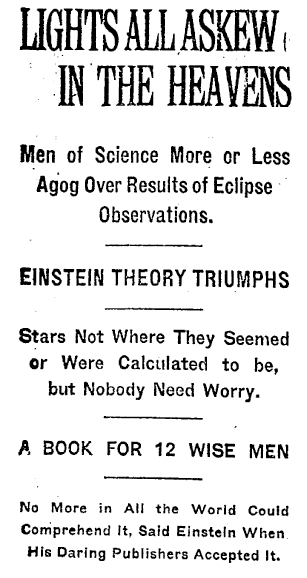

Headings and publication titles

In English-language publications, various conventions are used for the capitalisation of words in publication titles andheadline

The headline or heading is the text indicating the content or nature of the article below it, typically by providing a form of brief summary of its contents.

The large type ''front page headline'' did not come into use until the late 19th centur ...

s, including chapter and section headings. The rules differ substantially between individual house styles.

The convention followed by many British publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, newsp ...

s (including scientific publishers like ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' and ''New Scientist

''New Scientist'' is a magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. An editorially separate organisation publish ...

'', magazines like ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'', and newspapers like ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' and ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'') and many U.S. newspapers is sentence-style capitalisation in headlines, i.e. capitalisation follows the same rules that apply for sentences. This convention is usually called ''sentence case''. It may also be applied to publication titles, especially in bibliographic references and library catalogues. An example of a global publisher whose English-language house style prescribes sentence-case titles and headings is the International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ) is an international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries. Membership requirements are given in Art ...

(ISO).

For publication titles it is, however, a common typographic practice among both British and U.S. publishers to capitalise significant words (and in the United States, this is often applied to headings, too). This family of typographic conventions is usually called ''title case

Title case or headline case is a style of capitalization used for rendering the titles of published works or works of art in English. When using title case, all words are capitalized, except for minor words (typically articles, short prepositions, ...

''. For example, R. M. Ritter's ''Oxford Manual of Style'' (2002) suggests capitalising "the first word and all nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs, but generally not articles, conjunctions and short prepositions". This is an old form of emphasis, similar to the more modern practice of using a larger or boldface font for titles. The rules which prescribe which words to capitalise are not based on any grammatically inherent correct–incorrect distinction and are not universally standardised; they differ between style guides, although most style guides tend to follow a few strong conventions, as follows:

* Most styles capitalise all words except for short closed-class words (certain parts of speech, namely, articles, prepositions, and conjunctions); but the first word (always) and last word (in many styles) are also capitalised, regardless of their part of speech. Many styles capitalise longer prepositions such as "between" and "throughout", but not shorter ones such as "for" and "with". Typically, a preposition is considered short if it has up to three or four letters.

* A few styles capitalise all words in title case (the so-called ''start case''), which has the advantage of being easy to implement and hard to get "wrong" (that is, "not edited to style"). Because of this rule's simplicity, software case-folding routines can handle 95% or more of the editing, especially if they are programmed for desired exceptions (such as "FBI" rather than "Fbi").

* As for whether hyphenated words are capitalised not only at the beginning but also after the hyphen, there is no universal standard; variation occurs in the wild

''In The Wild'' is a popular nature television series produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation from 1976 until 1981. It was hosted by Harry Butler, a noted Australian naturalist and environmental consultant.

The re-runs of ''In The ...

and among house styles (e.g., "The Letter-''C''ase Rule in My Book"; "Short-''t''erm Follow-''u''p Care for Burns"). Traditional copyediting makes a distinction between ''temporary compounds'' (such as many nonce ovel instance compound modifiers), in which every part of the hyphenated word is capitalised (e.g. "How This Particular Author Chose to Style His ''A''utumn-''A''pple-''P''icking Heading"), and ''permanent compounds'', which are terms that, although compound and hyphenated, are so well established that dictionaries enter them as headword

In morphology and lexicography, a lemma (plural ''lemmas'' or ''lemmata'') is the canonical form, dictionary form, or citation form of a set of word forms. In English, for example, ''break'', ''breaks'', ''broke'', ''broken'' and ''breaking'' ...

s (e.g., "Short-''t''erm Follow-''u''p Care for Burns").

Title case is widely used in many English-language publications, especially in the United States. However, its conventions are sometimes not followed strictly especially in informal writing.

In creative typography, such as music record covers and other artistic material, all styles are commonly encountered, including all-lowercase letters and special case styles, such as studly caps (see below). For example, in the wordmarks of video games it is not uncommon to use stylised upper-case letters at the beginning and end of a title, with the intermediate letters in small caps or lower case (e.g., , , and DmC).

Multi-word proper nouns

Single-wordproper nouns

A proper noun is a noun that identifies a single entity and is used to refer to that entity (''Africa'', ''Jupiter'', ''Sarah'', ''Microsoft)'' as distinguished from a common noun, which is a noun that refers to a class of entities (''continent, ...

are capitalised in formal written English, unless the name is intentionally stylised to break this rule (such as the first or last name of danah boyd

danah boyd (stylized in lowercase, born November 24, 1977 as Danah Michele Mattas) She noted her mother added lowercase 'h' in birth name "danah" for typographical balance, reflecting the lowercase first letter 'd' and later changed her last na ...

).

Multi-word proper nouns include names of organisations, publications, and people. Often the rules for "title case" (described in the previous section) are applied to these names, so that non-initial articles, conjunctions, and short prepositions are lowercase, and all other words are uppercase. For example, the short preposition "of" and the article "the" are lowercase in "Steering Committee of the Finance Department". Usually only capitalised words are used to form an acronym

An acronym is a word or name formed from the initial components of a longer name or phrase. Acronyms are usually formed from the initial letters of words, as in ''NATO'' (''North Atlantic Treaty Organization''), but sometimes use syllables, as ...

variant of the name, though there is some variation in this.

With personal names, this practice can vary (sometimes all words are capitalised, regardless of length or function), but is not limited to English names. Examples include the English names Tamar of Georgia and Catherine the Great, " van" and "der" in Dutch name

Dutch names consist of one or more given names and a surname. The given name is usually gender-specific.

Dutch given names

A Dutch child's birth and given name(s) must be officially registered by the parents within 3 days after birth. It is not u ...

s, " von" and "zu" in German, "de", "los", and "y" in Spanish names, "de" or "d'" in French name

French names typically consist of one or multiple given names, and a surname. Usually one given name and the surname are used in a person’s daily life, with the other given names used mainly in official documents. Middle names, in the English ...

s, and "ibn" in Arabic names.

Some surname prefixes also affect the capitalisation of the following internal letter or word, for example "Mac" in Celtic names and "Al" in Arabic names.

Unit symbols and prefixes in the metric system

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

.

* 1 S (one siemens) when used for the unit of electric conductance and admittance (named after Werner von Siemens

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; ; ; 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He foun ...

).

* 1 Sv (one sievert

The sievert (symbol: SvNot be confused with the sverdrup or the svedberg, two non-SI units that sometimes use the same symbol.) is a unit in the International System of Units (SI) intended to represent the stochastic health risk of ionizing rad ...

), used for the unit of ionising radiation dose (named after Rolf Maximilian Sievert

Rolf Maximilian Sievert (; 6 May 1896 – 3 October 1966) was a Swedish medical physicist whose major contribution was in the study of the biological effects of ionizing radiation.

Sievert was born in Stockholm, Sweden. His parents were Ma ...

).

For the purpose of clarity, the symbol for litre

The litre (international spelling) or liter (American English spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metre (m3 ...

can optionally be written in upper case even though the name is not derived from a proper noun. For example, "one litre" may be written as:

* 1 l, the original form, for typefaces in which "digit one" , "lower-case ell" , and "upper-case i" look different.

* 1 L, an alternative form, for typefaces in which these characters are difficult to distinguish, or the typeface the reader will be using is unknown. A " script l" in various typefaces (e.g.: 1 l) has traditionally been used in some countries to prevent confusion; however, the separate Unicode character

The Unicode Consortium and the ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/ WG 2 jointly collaborate on the list of the characters in the Universal Coded Character Set. The Universal Coded Character Set, most commonly called the Universal Character Set ( UCS, offici ...

which represents this, , is deprecated by the SI. Another solution sometimes seen in Web typography is to use a serif font for "lower-case ell" in otherwise sans-serif material (1 l).

The letter case of a prefix symbol is determined independently of the unit symbol to which it is attached. Lower case is used for all submultiple prefix symbols and the small multiple prefix symbols up to "k" (for kilo

KILO (94.3 FM broadcasting, FM, 94.3 KILO) is a radio station broadcasting in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Colorado Springs and Pueblo, Colorado, Pueblo, Colorado. It also streams online.

History

KLST and KPIK-FM

The 94.3 signal signed on th ...

, meaning 103 = 1000 multiplier), whereas upper case is used for larger multipliers:

* 1 ms, millisecond, a small measure of time ("m" for milli

''Milli'' (symbol m) is a unit prefix in the metric system denoting a factor of one thousandth (10−3). Proposed in 1793, and adopted in 1795, the prefix comes from the Latin , meaning ''one thousand'' (the Latin plural is ). Since 1960, the pre ...

, meaning 10−3 = 1/1000 multiplier).

* 1 Ms, megasecond, a large measure of time ("M" for mega

Mega or MEGA may refer to:

Science

* mega-, a metric prefix denoting 106

* Mega (number), a certain very large integer in Steinhaus–Moser notation

* "mega-" a prefix meaning "large" that is used in taxonomy

* Gravity assist, for ''Moon-Eart ...

, meaning 106 = 1 000 000 multiplier).

* 1 mS, millisiemens, a small measure of electric conductance.

* 1 MS, megasiemens, a large measure of electric conductance.

* 1 mm, millimetre, a small measure of length.

* 1 Mm, megametre, a large measure of length.

Use within programming languages

Some case styles are not used in standard English, but are common incomputer programming

Computer programming is the process of performing a particular computation (or more generally, accomplishing a specific computing result), usually by designing and building an executable computer program. Programming involves tasks such as anal ...

, product brand

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create ...

ing, or other specialised fields.

The usage derives from how programming languages are parsed

Parsing, syntax analysis, or syntactic analysis is the process of analyzing a String (computer science), string of Symbol (formal), symbols, either in natural language, computer languages or data structures, conforming to the rules of a formal gra ...

, programmatically. They generally separate their syntactic tokens by simple whitespace, including space character

In computer programming, whitespace is any character or series of characters that represent horizontal or vertical space in typography. When rendered, a whitespace character does not correspond to a visible mark, but typically does occupy an area ...

s, tabs, and newlines. When the tokens, such as function and variable names start to multiply in complex software development, and there is still a need to keep the source code

In computing, source code, or simply code, is any collection of code, with or without comments, written using a human-readable programming language, usually as plain text. The source code of a program is specially designed to facilitate the w ...

human-readable, Naming conventions

A naming convention is a convention (generally agreed scheme) for naming things. Conventions differ in their intents, which may include to:

* Allow useful information to be deduced from the names based on regularities. For instance, in Manhatta ...

make this possible. So for example, a function dealing with matrix multiplication might formally be called:

** ''SGEMM(*)'', with the asterisk standing in for an equally inscrutable list of 13 parameters (in BLAS

Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms (BLAS) is a specification that prescribes a set of low-level routines for performing common linear algebra operations such as vector addition, scalar multiplication, dot products, linear combinations, and matrix ...

),

** ''MultiplyMatrixByMatrix(Matrix x, Matrix y)'', in some hypothetical higher level manifestly typed language, broadly following the syntax of C++

C++ (pronounced "C plus plus") is a high-level general-purpose programming language created by Danish computer scientist Bjarne Stroustrup as an extension of the C programming language, or "C with Classes". The language has expanded significan ...

or Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

,

** ''multiply-matrix-by-matrix(x, y)'' in something derived from LISP, or perhaps

** ''(multiply (x y))'' in the CLOS

Clos may refer to:

People

* Clos (surname)

Other uses

* CLOS, Command line-of-sight, a method of guiding a missile to its intended target

* Clos network, a kind of multistage switching network

* Clos (vineyard), a walled vineyard; used in Fran ...

, or some newer derivative language supporting type inference and multiple dispatch

Multiple dispatch or multimethods is a feature of some programming languages in which a function or method can be dynamically dispatched based on the run-time (dynamic) type or, in the more general case, some other attribute of more than one of ...

.

In each case the capitalisation or lack thereof supports a different function. In the first, FORTRAN compatibility requires case-insensitive naming and short function names. The second supports easily discernible function and argument names and types, within the context of an imperative, strongly typed language. The third supports the macro facilities of LISP, and its tendency to view programs and data minimalistically, and as interchangeable. The fourth idiom needs much less syntactic sugar

In computer science, syntactic sugar is syntax within a programming language that is designed to make things easier to read or to express. It makes the language "sweeter" for human use: things can be expressed more clearly, more concisely, or in an ...

overall, because much of the semantics are implied, but because of its brevity and so lack of the need for capitalization or multipart words at all, might also make the code too abstract and overloaded for the common programmer to understand.

Understandably then, such coding conventions are highly subjective, and can lead to rather opinionated debate, such as in the case of editor wars, or those about indent style

In computer programming, an indentation style is a convention governing the indentation of blocks of code to convey program structure. This article largely addresses the free-form languages, such as C and its descendants, but can be (and oft ...

. Capitalisation is no exception.

Camel case

Camel case: "theQuickBrownFoxJumpsOverTheLazyDog" or "TheQuickBrownFoxJumpsOverTheLazyDog"Spaces and

punctuation

Punctuation (or sometimes interpunction) is the use of spacing, conventional signs (called punctuation marks), and certain typographical devices as aids to the understanding and correct reading of written text, whether read silently or aloud. An ...

are removed and the first letter of each word is capitalised. If this includes the first letter of the first word (CamelCase, " PowerPoint", "TheQuick...", etc.), the case is sometimes called upper camel case (or, illustratively, CamelCase), Pascal case in reference to the Pascal programming language or bumpy case.

When the first letter of the first word is lowercase (" iPod", "eBay

eBay Inc. ( ) is an American multinational e-commerce company based in San Jose, California, that facilitates consumer-to-consumer and business-to-consumer sales through its website. eBay was founded by Pierre Omidyar in 1995 and became ...

", "theQuickBrownFox..."), the case is usually known as lower camel case or dromedary case (illustratively: dromedaryCase). This format has become popular in the branding of information technology

Information technology (IT) is the use of computers to create, process, store, retrieve, and exchange all kinds of Data (computing), data . and information. IT forms part of information and communications technology (ICT). An information te ...

products and services, with an initial "i" meaning "Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

" or "intelligent", as in iPod, or an initial "e" meaning "electronic", as in email

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic ( digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" mean ...

(electronic mail) or e-commerce

E-commerce (electronic commerce) is the activity of electronically buying or selling of products on online services or over the Internet. E-commerce draws on technologies such as mobile commerce, electronic funds transfer, supply chain managem ...

(electronic commerce).

Snake case

Snake case: "the_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog"Punctuation is removed and spaces are replaced by single

underscore

An underscore, ; also called an underline, low line, or low dash; is a line drawn under a segment of text. In proofreading, underscoring is a convention that says "set this text in italic type", traditionally used on manuscript or typescript a ...

s. Normally the letters share the same case (e.g. "UPPER_CASE_EMBEDDED_UNDERSCORE" or "lower_case_embedded_underscore") but the case can be mixed, as in OCaml modules. The style may also be called ''pothole case'', especially in Python

Python may refer to:

Snakes

* Pythonidae, a family of nonvenomous snakes found in Africa, Asia, and Australia

** ''Python'' (genus), a genus of Pythonidae found in Africa and Asia

* Python (mythology), a mythical serpent

Computing

* Python (pro ...

programming, in which this convention is often used for naming variables. Illustratively, it may be rendered ''snake_case'', ''pothole_case'', etc. When all-upper-case, it may be referred to as ''screaming snake case'' (or ''SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE'') or ''hazard case''.

Kebab case

Kebab case: "the-quick-brown-fox-jumps-over-the-lazy-dog"Similar to snake case, above, except

hyphen

The hyphen is a punctuation mark used to join words and to separate syllables of a single word. The use of hyphens is called hyphenation. ''Son-in-law'' is an example of a hyphenated word. The hyphen is sometimes confused with dashes ( figure ...

s rather than underscores are used to replace spaces. It is also known as spinal case, param case, Lisp case in reference to the Lisp programming language

Lisp (historically LISP) is a family of programming languages with a long history and a distinctive, fully parenthesized prefix notation.

Originally specified in 1960, Lisp is the second-oldest high-level programming language still in common u ...

, or dash case (or illustratively as kebab-case). If every word is capitalised, the style is known as train case (''TRAIN-CASE'').

In CSS, all property names and most keyword values are primarily formatted in kebab case.

Studly caps

Studly caps: e.g. "tHeqUicKBrOWnFoXJUmpsoVeRThElAzydOG"Mixed case with no semantic or syntactic significance to the use of the capitals. Sometimes only

vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s are upper case, at other times upper and lower case are alternated, but often it is simply random. The name comes from the sarcastic or ironic implication that it was used in an attempt by the writer to convey their own coolness. It is also used to mock the violation of standard English case conventions by marketers in the naming of computer software packages, even when there is no technical requirement to do soe.g., Sun Microsystems' naming of a windowing system NeWS

News is information about current events. This may be provided through many different media: word of mouth, printing, postal systems, broadcasting, electronic communication, or through the testimony of observers and witnesses to events. N ...

. Illustrative naming of the style is, naturally, random: ''stUdlY cAps'', ''StUdLy CaPs'', etc.

Case folding and case conversion

In thecharacter set

Character encoding is the process of assigning numbers to graphical characters, especially the written characters of human language, allowing them to be stored, transmitted, and transformed using digital computers. The numerical values tha ...

s developed for computing

Computing is any goal-oriented activity requiring, benefiting from, or creating computing machinery. It includes the study and experimentation of algorithmic processes, and development of both hardware and software. Computing has scientific, ...

, each upper- and lower-case letter is encoded as a separate character. In order to enable case folding and case conversion, the software

Software is a set of computer programs and associated software documentation, documentation and data (computing), data. This is in contrast to Computer hardware, hardware, from which the system is built and which actually performs the work.

...

needs to link together the two characters representing the case variants of a letter. (Some old character-encoding systems, such as the Baudot code

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by Émile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII ...

, are restricted to one set of letters, usually represented by the upper-case variants.)

Case-insensitive operations can be said to fold case, from the idea of folding the character code table so that upper- and lower-case letters coincide. The conversion of letter case in a string is common practice in computer applications, for instance to make case-insensitive comparisons. Many high-level programming languages provide simple methods for case conversion, at least for the ASCII

ASCII ( ), abbreviated from American Standard Code for Information Interchange, is a character encoding standard for electronic communication. ASCII codes represent text in computers, telecommunications equipment, and other devices. Because ...

character set.

Whether or not the case variants are treated as equivalent to each other varies depending on the computer system and context. For example, user password

A password, sometimes called a passcode (for example in Apple devices), is secret data, typically a string of characters, usually used to confirm a user's identity. Traditionally, passwords were expected to be memorized, but the large number of ...

s are generally case sensitive in order to allow more diversity and make them more difficult to break. In contrast, case is often ignored in keyword search

A search engine is an information retrieval software program that discovers, crawls, transforms and stores information for retrieval and presentation in response to user queries.

A search engine normally consists of four components, that are sear ...

es in order to ignore insignificant variations in keyword capitalisation both in queries and queried material.

Unicode case folding and script identification

Unicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, wh ...

defines case folding through the three case-mapping properties of each character: upper case, lower case, and title case (in this context, "title case" relates to ligature

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

s and digraphs encoded as mixed-case single characters, in which the first component is in upper case and the second component in lower case). These properties relate all characters in scripts with differing cases to the other case variants of the character.

As briefly discussed in Unicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, wh ...

Technical Note #26, "In terms of implementation issues, any attempt at a unification of Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic would wreak havoc ndmake casing operations an unholy mess, in effect making all casing operations context sensitive ��. In other words, while the shapes of letters like A, B, E, H, K, M, O, P, T, X, Y and so on are shared between the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets (and small differences in their canonical forms may be considered to be of a merely typographical nature), it would still be problematic for a multilingual character set

Character encoding is the process of assigning numbers to graphical characters, especially the written characters of human language, allowing them to be stored, transmitted, and transformed using digital computers. The numerical values tha ...

or a font to provide only a ''single'' code point

In character encoding terminology, a code point, codepoint or code position is a numerical value that maps to a specific character. Code points usually represent a single grapheme—usually a letter, digit, punctuation mark, or whitespace—but ...

for, say, uppercase letter B, as this would make it quite difficult for a wordprocessor to change that single uppercase letter to one of the three different choices for the lower-case letter, the Latin b (U+0062), Greek β (U+03B2) or Cyrillic в (U+0432). Therefore, the corresponding Latin, Greek and Cyrillic upper-case letters (U+0042, U+0392 and U+0412, respectively) are also encoded as separate characters, despite their appearance being basically identical. Without letter case, a "unified European alphabet"such as ABБCГDΔΕЄЗFΦGHIИJ...Z, with an appropriate subset for each languageis feasible; but considering letter case, it becomes very clear that these alphabets are rather distinct sets of symbols.

Methods in word processing

Most modernword processor

A word processor (WP) is a device or computer program that provides for input, editing, formatting, and output of text, often with some additional features.

Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to the function, but current ...

s provide automated case conversion with a simple click or keystroke. For example, in Microsoft Office Word, there is a dialog box for toggling the selected text through UPPERCASE, then lowercase, then Title Case (actually start caps; exception words must be lowercased individually). The keystroke does the same thing.

Methods in programming

In some forms of BASIC there are two methods for case conversion:C++

C++ (pronounced "C plus plus") is a high-level general-purpose programming language created by Danish computer scientist Bjarne Stroustrup as an extension of the C programming language, or "C with Classes". The language has expanded significan ...

, as well as any C-like language that conforms to its standard library, provide these functions in the file ctype.h:

character sets

Character encoding is the process of assigning numbers to graphical characters, especially the written characters of human language, allowing them to be stored, transmitted, and transformed using digital computers. The numerical values that ...

. In ASCII

ASCII ( ), abbreviated from American Standard Code for Information Interchange, is a character encoding standard for electronic communication. ASCII codes represent text in computers, telecommunications equipment, and other devices. Because ...

or EBCDIC

Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC; ) is an eight- bit character encoding used mainly on IBM mainframe and IBM midrange computer operating systems. It descended from the code used with punched cards and the corresponding ...

, case can be converted in the following way, in C:

Visual Basic Visual Basic is a name for a family of programming languages from Microsoft. It may refer to:

* Visual Basic .NET (now simply referred to as "Visual Basic"), the current version of Visual Basic launched in 2002 which runs on .NET

* Visual Basic ( ...

calls this "proper case"; Python

Python may refer to:

Snakes

* Pythonidae, a family of nonvenomous snakes found in Africa, Asia, and Australia

** ''Python'' (genus), a genus of Pythonidae found in Africa and Asia

* Python (mythology), a mythical serpent

Computing

* Python (pro ...

calls it "title case". This differs from usual title casing conventions, such as the English convention in which minor words are not capitalised.

History

Originallyalphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syllab ...

s were written entirely in majuscule letters, spaced between well-defined upper and lower bounds. When written quickly with a pen

A pen is a common writing instrument that applies ink to a surface, usually paper, for writing or drawing. Early pens such as reed pens, quill pens, dip pens and ruling pens held a small amount of ink on a nib or in a small void or cavity wh ...

, these tended to turn into rounder and much simpler forms. It is from these that the first minuscule hands developed, the half-uncials and cursive minuscule, which no longer stayed bound between a pair of lines. These in turn formed the foundations for the Carolingian minuscule

Carolingian minuscule or Caroline minuscule is a script which developed as a calligraphic standard in the medieval European period so that the Latin alphabet of Jerome's Vulgate Bible could be easily recognized by the literate class from one reg ...

script, developed by Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

for use in the court of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

, which quickly spread across Europe. The advantage of the minuscule over majuscule was improved, faster readability.

In Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, papyri from Herculaneum dating before 79 CE (when it was destroyed) have been found that have been written in old Roman cursive

Roman cursive (or Latin cursive) is a form of handwriting (or a script) used in ancient Rome and to some extent into the Middle Ages. It is customarily divided into old (or ancient) cursive and new cursive.

Old Roman cursive

Old Roman cursiv ...

, where the early forms of minuscule letters "d", "h" and "r", for example, can already be recognised. According to papyrologist Knut Kleve, "The theory, then, that the lower-case letters have been developed from the fifth century uncial

Uncial is a majuscule Glaister, Geoffrey Ashall. (1996) ''Encyclopedia of the Book''. 2nd edn. New Castle, DE, and London: Oak Knoll Press & The British Library, p. 494. script (written entirely in capital letters) commonly used from the 4th to ...