, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge

, type =

Public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichk ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kn ...

, endowment = £7.121 billion (including colleges)

, budget = £2.308 billion (excluding colleges)

, chancellor =

The Lord Sainsbury of Turville

, vice_chancellor =

Anthony Freeling

, students = 24,450 (2020)

, undergrad = 12,850 (2020)

, postgrad = 11,600 (2020)

, city =

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, country = England

, campus_type =

, sporting_affiliations =

The Sporting Blue

, colours =

Cambridge Blue

, website =

, logo = University of Cambridge logo.svg

, logo_size = 255px

, academic_affiliations =

, faculty = 6,170 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 3,615 (excluding colleges)

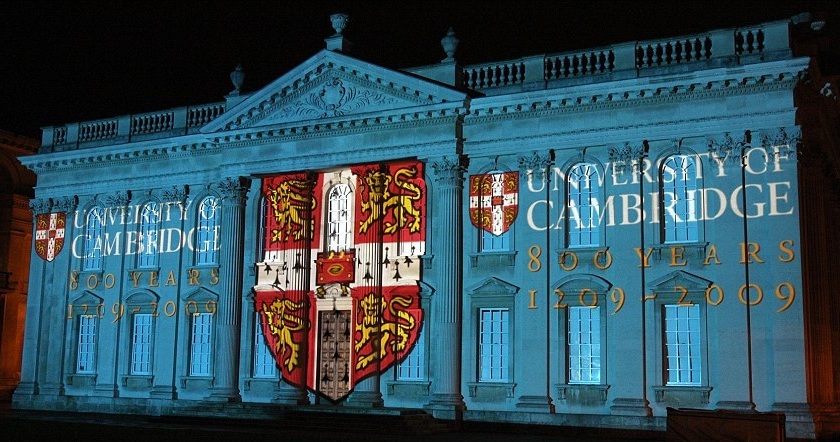

The University of Cambridge is a

public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichk ...

collegiate research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kn ...

in

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

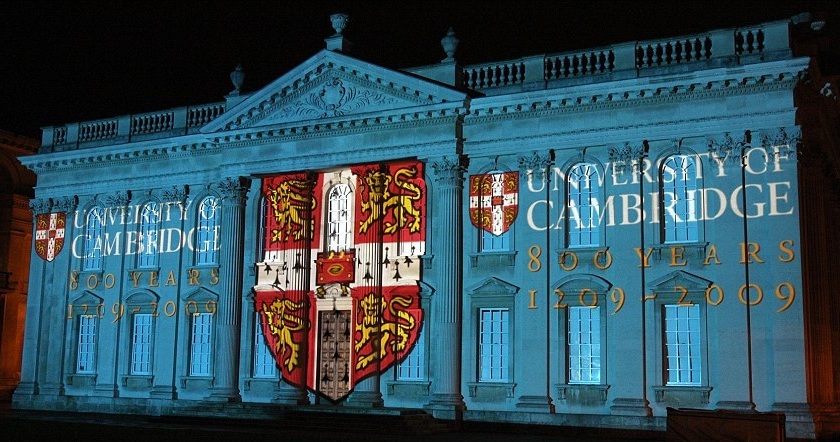

, England. Founded in 1209

and granted a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

by

Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's

third oldest surviving university and one of its most prestigious, currently ranked second-best in the world and the best in Europe by ''

QS World University Rankings

''QS World University Rankings'' is an annual publication of university rankings by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS). The QS system comprises three parts: the global overall ranking, the subject rankings (which name the world's top universities for the ...

''. Among the university's

most notable alumni are 11

Fields Medalists, seven

Turing Award winners, 47

heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

, 14

British prime ministers

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the principal minister of the crown of His Majesty's Government, and the head of the British Cabinet. There is no specific date for when the office of prime minister first appeared, as the role was no ...

, 194

Olympic medal

An Olympic medal is awarded to successful competitors at one of the Olympic Games. There are three classes of medal to be won: gold, silver, and bronze, awarded to first, second, and third place, respectively. The granting of awards is laid o ...

-winning athletes,

[All Known Cambridge Olympians]

. ''Hawks Club''. Retrieved 17 May 2019. and some of world history's most transformational and iconic figures across disciplines, including

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

,

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

,

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

,

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

,

Stephen Hawking,

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

,

John Milton,

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

,

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

,

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

,

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

,

Manmohan Singh,

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical co ...

,

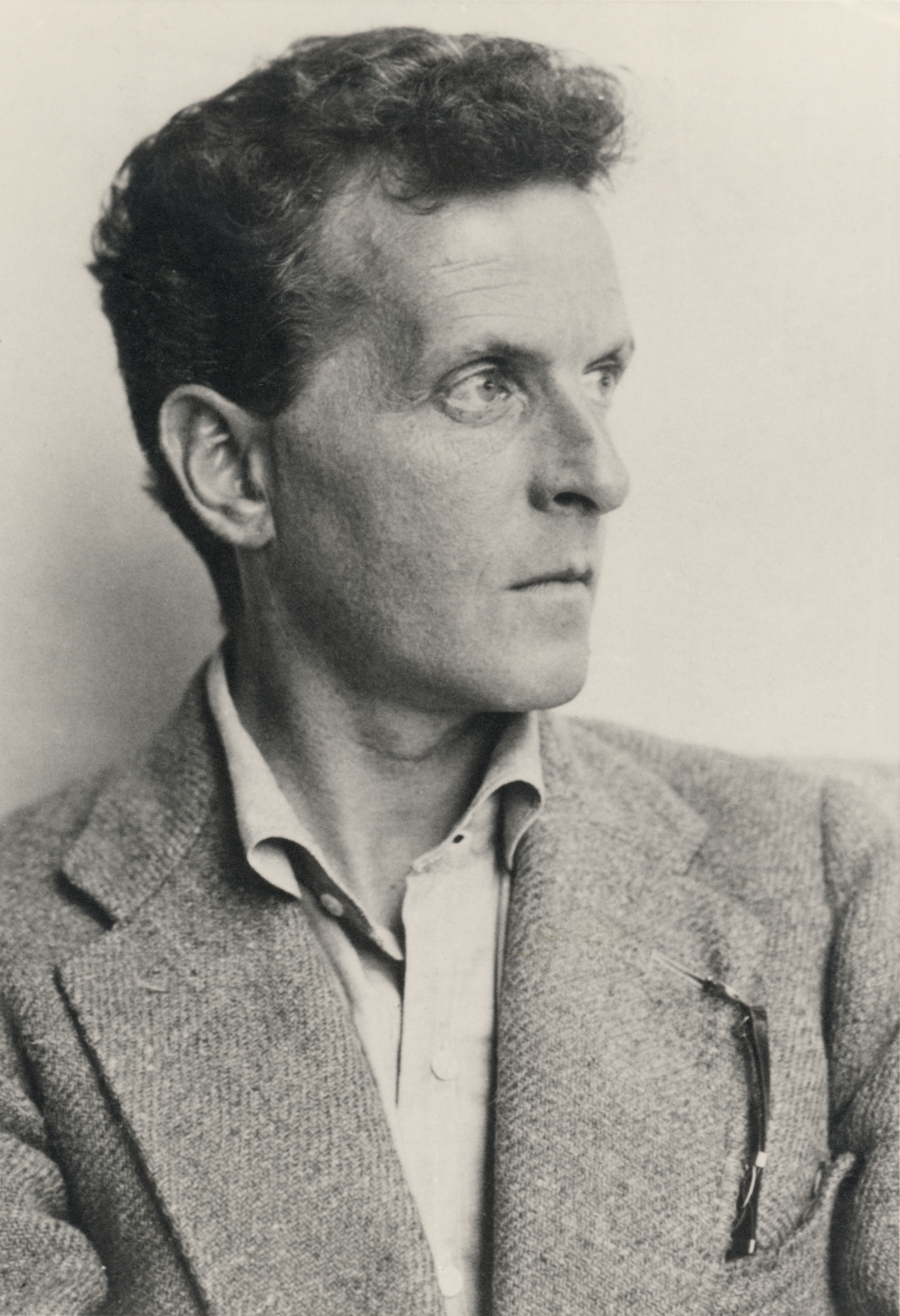

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

, and others. Cambridge alumni and faculty have won 121

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

s, the most of any university in the world, according to the university.

The University of Cambridge's 13th-century founding was largely inspired by an association of scholars then who fled the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

for Cambridge following the ''suspendium clericorium'' (hanging of the scholars) in a dispute with local townspeople. The two

ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

English universities, though sometimes described as rivals, share many common features and are often jointly referred to as ''

Oxbridge''. The university was founded from a variety of institutions, including

31 semi-autonomous constituent colleges and

over 150 academic departments, faculties, and other institutions organised into six schools. All the colleges are self-governing institutions within the university, managing their own personnel and policies, and all students are required to have a college affiliation within the university. The university does not have a main campus, and its colleges and central facilities are scattered throughout the city. Undergraduate teaching at Cambridge centres on weekly group

supervisions in the colleges in small groups of typically one to four students. This intensive method of teaching is widely considered the jewel in the crown of an Oxbridge undergraduate education. Lectures, seminars, laboratory work, and occasionally further supervisions are provided by the central university faculties and departments, and Postgraduate education is also predominantly provided centrally; degrees, however, are conferred by the university, not the colleges.

By both

endowment size and material consolidated assets, Cambridge is the wealthiest university in Europe and among the wealthiest in the world. In the 2019 fiscal year, the central university, excluding colleges, had total income of £2.192 billion, £592.4 million of which was from research grants and contracts.

The central university and colleges together possessed a combined endowment of over £7.1 billion and overall consolidated net assets, excluding immaterial historical assets, of over £12.5 billion.

Cambridge University Press & Assessment combines

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

, the world's oldest university press, with one of the world's leading examining bodies; their publications reach in excess of eight million learners globally each year and some fifty million learners, teachers, and researchers monthly. The university operates eight cultural and scientific museums, including the

Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th Vis ...

and

Cambridge University Botanic Garden

The Cambridge University Botanic Garden is a botanical garden located in Cambridge, England, associated with the university Department of Plant Sciences (formerly Botany School). It lies between Trumpington Road to the west, Bateman Street to ...

.

Cambridge's 116 libraries hold a total of around 16 million books, around nine million of which are in

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

, a

legal deposit library and one of the world's largest academic libraries.

Cambridge Union

The Cambridge Union Society, also known as the Cambridge Union, is a debating and free speech society in Cambridge, England, and the largest society in the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1815, it is the oldest continuously running debati ...

, the world's oldest debating society founded in 1815, inspired the emergence of university debating societies globally, including at

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. The university is closely linked to the high technology

business cluster

A business cluster is a geographic concentration of interconnected businesses, suppliers, and associated institutions in a particular field. Clusters are considered to increase the productivity with which companies can compete, nationally and gl ...

known as

Silicon Fen

Silicon Fen (also known as the Cambridge Cluster) is the name given to the region around Cambridge, England, which is home to a large business cluster, cluster of high-tech businesses focusing on software, electronics and biotechnology, s ...

, Europe's largest technology cluster. The university is also the central member of

Cambridge University Health Partners

Cambridge University Health Partners is an academic health science centre that brings together the University of Cambridge, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Cambridgeshire and Pe ...

, an

academic health science centre based around the

Cambridge Biomedical Campus

The Cambridge Biomedical Campus is the largest centre of medical research and health science in Europe. The site is located at the southern end of Hills Road in Cambridge, England.

Over 20,000 people work at the site, which is home to Cambridge ...

, which is Europe's largest medical and science centre.

History

Founding

Prior to the founding of the University of Cambridge in 1209, Cambridge and the area surrounding it already had developed a scholarly and ecclesiastical reputation, due largely to the intellectual reputation and contribution of monks from the nearby bishopric church of

Ely. The founding of the University of Cambridge, however, was inspired largely by an incident at

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

during which three Oxford scholars, as an administration of justice in the death of a local woman, were

hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

by town authorities without first consulting ecclesiastical authorities, who traditionally would be inclined to pardon scholars in such cases. But during this time,

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

's town authorities were in conflict with

King John. Fearing more violence from Oxford townsfolk, University of Oxford scholars consequently began leaving Oxford for other more hospitable cities, including

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

,

Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spelling ...

, and

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. Enough scholars ultimately took residence in Cambridge to form the nucleus for the formation of a new university.

In order to lay controversial claim to being England's oldest university, Cambridge often traces its founding to

Henry III's 1231 charter, which granted the University of Cambridge the right to discipline its own members (''ius non-trahi extra'') and an exemption from some taxes.

Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

' s

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

gave Cambridge graduates the right to teach everywhere in

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

. After Cambridge was described as a ''

studium generale

is the old customary name for a medieval university in medieval Europe.

Overview

There is no official definition for the term . The term ' first appeared at the beginning of the 13th century out of customary usage, and meant a place where stud ...

'' in a letter from

Pope Nicholas IV

Pope Nicholas IV ( la, Nicolaus IV; 30 September 1227 – 4 April 1292), born Girolamo Masci, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 February 1288 to his death on 4 April 1292. He was the first Franciscan to be ele ...

in 1290,

and confirmed as such

Pope John XXII's 1318 papal bull, it became common for researchers from other European

medieval universities to visit Cambridge to study or to give lecture courses.

Foundation of the colleges

The

colleges at the University of Cambridge were originally an incidental feature of the university; no college is as old as the university itself. The colleges were endowed fellowships of scholars. There were also institutions without endowments, called hostels, which were gradually absorbed by the colleges over the centuries, and they have left some traces, such as the name Garret Hostel Lane.

Hugh de Balsham

Hugh de Balsham (or Hugo; died 16 June 1286) was a medieval English bishop.

Life

Nothing is known of Balsham's background, although during the dispute over his election he was alleged to have been of servile birth, and his name suggests a conn ...

,

Bishop of Ely, founded

Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite o ...

, Cambridge's first college, in 1284. Multiple additional colleges were founded during the 14th and 15th centuries, but colleges continued being established through modern times, though there was a 204-year gap between the founding of

Sidney Sussex in 1596 and that of

Downing in 1800. The most recent college to be established is

Robinson Robinson may refer to:

People and names

* Robinson (name)

Fictional characters

* Robinson Crusoe, the main character, and title of a novel by Daniel Defoe, published in 1719

Geography

* Robinson projection, a map projection used since the 1960 ...

, which was built in the late 1970s. However,

Homerton College only achieved full university college status in March 2010, making it technically the newest full college.

In

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

times, many colleges were founded so that their members could

pray

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified a ...

for the

soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

s of the founders. University of Cambridge colleges often were associated with chapels or

abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The con ...

s. The colleges' focus began to shift in 1536, however, with the

Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Henry VIII ordered the university to disband its Faculty of

canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

and to stop teaching

scholastic philosophy. In response, colleges changed their curricula away from canon law, and towards the

classics, the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

, and mathematics.

Nearly a century later, the university found itself at the centre of a

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

schism. Many nobles, intellectuals, and even commoners saw the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

as too similar to the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and felt that it was being used by

The Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

to usurp the counties' rightful powers.

East Anglia emerged as the centre of what ultimately became the

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

movement. In Cambridge, the Puritan movement was particularly strong at Emmanuel, St Catharine's Hall, Sidney Sussex, and

Christ's College. These colleges produced many non-conformist graduates who greatly influenced, by social position or preaching, some 20,000 Puritans who ultimately left England for

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

and especially the

Massachusetts Bay Colony during the

Great Migration decade of the 1630s, becoming

America's first settlers.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

, Parliamentary commander during the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

and head of the English Commonwealth from 1649 to 1660, attended

Sidney Sussex.

Mathematics and mathematical physics

The university quickly established itself as a global leader in the study of

mathematics.

Examination in mathematics was initially compulsory for all undergraduates studying for the

Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

degree, the most common degree first offered at Cambridge. From the time of

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

in the late 17th century until the mid-19th century, the university maintained an especially strong emphasis on

applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathemati ...

, particularly

mathematical physics

Mathematical physics refers to the development of mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The '' Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the developme ...

. The university established a mathematics exam known as a

Tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mathe ...

. Students awarded

first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

after completing the mathematics Tripos exam are called

wranglers, and the top student among them is known as the

Senior Wrangler

The Senior Frog Wrangler is the top mathematics undergraduate at the University of Cambridge in England, a position which has been described as "the greatest intellectual achievement attainable in Britain."

Specifically, it is the person who a ...

, a position that has been described as "the greatest intellectual achievement attainable in Britain."

The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos is highly competitive and has helped produce some of the most famous names in British science, including

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

,

Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

, and

Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, (; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919) was an English mathematician and physicist who made extensive contributions to science. He spent all of his academic career at the University of Cambridge. Am ...

. However, some famous students, such as

G. H. Hardy, disliked the Tripos system, feeling that students were becoming too interested in accumulating high exam marks and less interested in the subject itself.

Pure mathematics at Cambridge in the 19th century achieved great things, but also missed out on substantial developments in French and German mathematics. Pure mathematical research at Cambridge finally reached the highest international standard in the early 20th century, thanks largely to G. H. Hardy and his collaborators,

J. E. Littlewood and

Srinivasa Ramanujan.

W. V. D. Hodge established Cambridge as a global leader in

geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

in the 1930s.

Although diversified in its research and teaching interests, Cambridge today maintains its traditional strength as a world leader in the teaching of mathematics. Cambridge alumni have won six

Fields Medals and one

Abel Prize for mathematics, and individuals representing Cambridge have won four additional Fields Medals.

Modern period

The

Cambridge University Act 1856

The Cambridge University Act 1856The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by the Short Titles Act 1896, section 1 and the first schedule. Due to the repeal of those provisions it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpr ...

formalised the university's organisational structure and introduced the study of many new subjects, including theology, history and

Modern language

A modern language is any human language that is currently in use. The term is used in language education to distinguish between languages which are used for day-to-day communication (such as French and German) and dead classical languages such a ...

s. Resources necessary for new courses in the arts, architecture, and

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

were donated by

Viscount Fitzwilliam

Viscount FitzWilliam, of Merrion in the County of Dublin, was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1629 for Thomas FitzWilliam, along with the subsidiary title Baron FitzWilliam, of Thorncastle in the County of Dublin, also in th ...

of

Trinity College, who also founded the

Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th Vis ...

. In 1847,

Prince Albert was elected the university's chancellor in a close contest with the

Earl of Powis

Earl of Powis (Powys) is a title that has been created three times. The first creation came in the Peerage of England in 1674 in favour of William Herbert, 3rd Baron Powis, a descendant of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (c. 1501–15 ...

. As chancellor, Albert reformed university curricula beyond its initial focus on mathematics and classics, adding modern history and the natural sciences. Between 1896 and 1902,

Downing College

Downing College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge and currently has around 650 students. Founded in 1800, it was the only college to be added to Cambridge University between 1596 and 1869, and is often described as the olde ...

sold part of its land to permit the construction of

Downing Site

The Downing Site is a major site of the University of Cambridge, located in the centre of the city of Cambridge, England, on Downing Street and Tennis Court Road, adjacent to Downing College. The Downing Site is the larger and newer of two ci ...

, the university's new grouping of scientific laboratories for the study of

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

,

genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

, and

Earth sciences

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth. This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four spheres ...

. During this period, the

New Museums Site

The New Museums Site is a major site of the University of Cambridge, located on Pembroke Street and Free School Lane, sandwiched between Corpus Christi College, Pembroke College and Lion Yard. Its postcode is CB2 3QH. The smaller and older of ...

was erected, including the

Cavendish Laboratory, which has since moved to

West Cambridge

West Cambridge is a university site to the west of Cambridge city centre in England. As part of the ''West Cambridge Master Plan'', several of the University of Cambridge's departments have relocated to the West Cambridge site from the centre ...

, and other

departments for chemistry and medicine.

The University of Cambridge began to award

PhD degrees in the first third of the 20th century; the first Cambridge PhD in mathematics was awarded in 1924.

The university contributed significantly to the

Allies' forces in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

with 13,878 members of the university serving and 2,470 being killed in the war. Teaching, and the fees it earned, nearly came to a stop during World War I, and severe financial difficulties followed. As a result, the university received its first systematic state support in 1919, and a

Royal commission was appointed in 1920 to recommend that the university (but not its colleges) begin receiving an annual grant. Following

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the university experienced a rapid expansion in applications and enrollment, partly due to the success and popularity gained by many Cambridge scientists.

Parliamentary representation

Cambridge was one of only two universities to hold parliamentary seats in the

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

and was later one of only eight represented in the

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. The constituency was created by a

Royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

of 1603 and returned two members of parliament until 1950 when it was abolished by the

Representation of the People Act 1948

The Representation of the People Act 1948 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that altered the law relating to parliamentary and local elections. It is noteworthy for abolishing plural voting for parliamentary elections, including ...

. The constituency was not a geographical area; rather, its electorate consisted of university graduates. Before 1918, the franchise was restricted to male graduates with a

doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

or

MA degree.

Women's education

For the first several centuries of its existence, as was the case broadly in England and the world, the University of Cambridge was only open to male students. The first colleges established for women were

Girton College

Girton College is one of the Colleges of the University of Cambridge, 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1 ...

(founded by

Emily Davies

Sarah Emily Davies (22 April 1830 – 13 July 1921) was an English feminist and suffragist, and a pioneering campaigner for women's rights to university access. She is remembered above all as a co-founder and an early Mistress of Girton Coll ...

in 1869) and

Newnham College

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millice ...

(founded by

Anne Clough and

Henry Sidgwick

Henry Sidgwick (; 31 May 1838 – 28 August 1900) was an English utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected i ...

in 1872) followed by

Hughes Hall (founded in 1885 by

Elizabeth Phillips Hughes as the Cambridge Teaching College for Women),

Murray Edwards College

Murray Edwards College is a women-only constituent college of the University of Cambridge. It was founded in 1954 as New Hall. In 2008, following a donation of £30 million by alumna Ros Edwards and her husband Steve, it was renamed Murray Edwar ...

(founded in 1954 by

Rosemary Murray as

New Hall), and

Lucy Cavendish College

Lucy Cavendish College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college is named in honour of Lucy Cavendish (1841–1925), who campaigned for the reform of women's education.

History

The college was founded in 1965 by ...

in 1965. Prior to ultimately being permitted admission to the university, female students had been granted the right to take University of Cambridge exams beginning in the late 19th century. In 1948, the university officially permitted them entry to the university. Women were allowed to study courses, take examinations, and have prior exam results recorded retroactively, dating back to 1881; for a brief period after the turn of the 20th century, this allowed the

steamboat ladies

"Steamboat ladies" was a nickname given to a number of female students at the women's colleges of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge who were awarded ''ad eundem'' University of Dublin degrees at Trinity College Dublin, between 1904 and 19 ...

to receive ''

ad eundem

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to put a product or service in the spotlight in hopes of drawing it attention from consumers. It is typically used to promote a ...

'' degrees from the

University of Dublin.

Beginning in 1921, women were awarded diplomas that conferred the title associated with the Bachelor of Arts degree. But since women were not yet admitted to the Bachelor of Arts degree program, women were excluded from the university's governance structure. Since students must belong to a college, and since established colleges remained closed to women, women found admissions restricted to few university colleges that had been established only for them.

Darwin College, the first graduate college of the university, matriculated both male and female students from its inception in 1964 and elected a mixed fellowship. Among undergraduate colleges, starting with

Churchill,

Clare, and

King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

's Colleges, the former male-only colleges began to admit women between 1972 and 1988. Among female-only colleges,

Girton began admitting male students in 1979, and

Lucy Cavendish began admitting men in 2021. But the other female-only colleges have remained female-only colleges. As a result of

St Hilda's College, Oxford ending its ban on male students in 2008, Cambridge is now the only remaining university in the United Kingdom with female-only colleges (

Newnham and

Murray Edwards). As of the 2019–2020 academic year, the university's male to female enrollment, including post-graduates, was nearly balanced with its total student population being 53% male and 47% female.

Town and gown

The relationship between the university and the city has sometimes been uneasy. The phrase town and gown is employed to distinguish between Cambridge residents and University of Cambridge students, who historically wore

academical dress. There are many stories of ferocious rivalry between Cambridge's residents and university students. During the

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

of 1381, strong clashes led to attacks and

looting of university properties while locals contested the privileges granted by the government to the academic staff. Residents burned university property in

Market Square to the famed rallying cry "

Away with the learning of clerks, away with it!". Following these events, the University of Cambridge's Chancellor was given special powers allowing him to prosecute criminals and reestablish order in the city. Attempts at reconciliation between the city's residents and students followed. In the 16th century, agreements were signed to improve the quality of streets and student accommodation around the city. However, this was followed by new confrontations when the

plague reached Cambridge in 1630 and colleges refused to assist those affected by the disease by locking their sites.

Such conflicts between Cambridge's residents and university students have largely disappeared. The university is a source of enormous employment and expanded wealth in Cambridge and the region. The university also has proven a source of enormous growth in

high tech

High technology (high tech), also known as advanced technology (advanced tech) or exotechnology, is technology that is at the cutting edge: the highest form of technology available. It can be defined as either the most complex or the newest te ...

and

biotech start-ups and established companies and associated providers of services to these companies. The economic growth associated with the university's high tech and biotech growth has been labeled the Cambridge Phenomenon, and has included the addition of 1,500 new companies and as many as 40,000 new jobs added between 1960 and 2010.

Myths, legends and traditions

Partly because of the University of Cambridge's extensive eight century history, the university has developed a large number of traditions, myths, and legends. Some are true, some are not, and some were true but have been discontinued but have been propagated nonetheless by generations of students and tour guides.

One such discontinued tradition is that of the

wooden spoon Wooden Spoon may refer to:

* Wooden spoon, implement

* Wooden spoon (award)

A wooden spoon is an award that is given to an individual or team that has come last in a competition. Examples range from the academic to sporting and more frivolous e ...

, the prize awarded to the student with the lowest passing honours grade in the final examinations of the

Mathematical Tripos

The Mathematical Tripos is the mathematics course that is taught in the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. It is the oldest Tripos examined at the University.

Origin

In its classical nineteenth-century form, the tripos was ...

. The last of these spoons was awarded in 1909 to Cuthbert Lempriere Holthouse, an oarsman of the Lady Margaret Boat Club of

St John's College. It was over one metre in length and had an oar blade for a handle. It can now be seen outside the Senior Combination Room of St John's. Since 1908, examination results have been published alphabetically within class rather than in strict order of merit, which made it difficult to ascertain the student with the lowest passing grade deserving of the spoon, leading to discontinuation of the tradition.

Each

Christmas Eve,

The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols sung by the

Choir of King's College, Cambridge

The Choir of King's College, Cambridge is an English Anglican choir. It is considered one of today's most accomplished and renowned representatives of the great English choral tradition. It was created by King Henry VI, who founded King's Col ...

are broadcast globally on

BBC World Service television and radio and syndicated to hundreds of additional radio stations in the U.S. and elsewhere. The radio broadcast has been a national Christmas Eve tradition since 1928, though the festival has existed since 1918. The first television broadcast of the festival was in 1954.

Locations and buildings

Buildings

The university occupies a central location within the city of

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

with the students taking up a roughly 20 percent of the town's population, and contributing on whole to a lower age demographic in the city.

Most of the university's older colleges are situated nearby the city centre, through which flows

River Cam, which students and others traditionally

punt to appreciate the university buildings and surroundings viewable from the river.

Other notable buildings include

King's College Chapel

King's College Chapel is the chapel of King's College, Cambridge, King's College in the University of Cambridge. It is considered one of the finest examples of late Perpendicular Gothic English architecture and features the world's largest fan ...

, the history faculty building designed by

James Stirling, and the Cripps Building at

St John's College. The

brickwork

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by si ...

of several colleges is notable:

Queens' College has "some of the earliest patterned brickwork in the country" and the brick walls of St John's College provide examples of

English bond

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by siz ...

,

Flemish bond

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by siz ...

, and

Running bond

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by siz ...

.

Sites

The university is divided into several sites where departments are located. These include:

*

Addenbrooke's Hospital

Addenbrooke's Hospital is an internationally renowned large teaching hospital and research centre in Cambridge, England, with strong affiliations to the University of Cambridge. Addenbrooke's Hospital is based on the Cambridge Biomedical Camp ...

*

Downing Site

The Downing Site is a major site of the University of Cambridge, located in the centre of the city of Cambridge, England, on Downing Street and Tennis Court Road, adjacent to Downing College. The Downing Site is the larger and newer of two ci ...

* Madingley/Gorton

*

New Museums Site

The New Museums Site is a major site of the University of Cambridge, located on Pembroke Street and Free School Lane, sandwiched between Corpus Christi College, Pembroke College and Lion Yard. Its postcode is CB2 3QH. The smaller and older of ...

*

North West Cambridge Development

The North West Cambridge Development is a University of Cambridge site to the north west of Cambridge city centre in England. The development is meant to alleviate overcrowding and rising land prices in Cambridge. The first phase resulted from ...

*

Old Addenbrooke's Site

The Old Addenbrooke's Site is a site owned by the University of Cambridge in the south of central Cambridge, England.

It is located on the block formed by Fitzwilliam Street to the north, Tennis Court Road to the east, Lensfield Road to th ...

*

Old Schools

*

Silver Street

''Silver Street'' is a radio soap opera broadcast on the BBC Asian Network from 24 May 2004 to 26 March 2010. It was the first soap to be aimed at the British South Asian community,

Broadcast history

It was introduced in 2004 as part of the S ...

/

Mill Lane

*

Sidgwick Site

The Sidgwick Site is one of the largest sites within the University of Cambridge, England.

Overview and history

The Sidgwick Site is located on the western side of Cambridge city centre, near the Backs. The site is north of Sidgwick Avenue an ...

*

West Cambridge

West Cambridge is a university site to the west of Cambridge city centre in England. As part of the ''West Cambridge Master Plan'', several of the University of Cambridge's departments have relocated to the West Cambridge site from the centre ...

The university's School of Clinical Medicine is based in

Addenbrooke's Hospital

Addenbrooke's Hospital is an internationally renowned large teaching hospital and research centre in Cambridge, England, with strong affiliations to the University of Cambridge. Addenbrooke's Hospital is based on the Cambridge Biomedical Camp ...

, where medical students undergo their three-year clinical placement period after obtaining their

BA degree. The West Cambridge site is undergoing a major expansion and will host new buildings and fields for university sports. Since 1990,

Cambridge Judge Business School

Cambridge Judge Business School is the business school of the University of Cambridge. The School is a provider of management education. It is named after Sir Paul Judge, a founding benefactor of the school.

The School is considered to be par ...

, on Trumpington Street, provides management education courses and is consistently ranked within the top 20 business schools globally by ''

Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Ni ...

''.

Given that the sites are in relative proximity and the area around Cambridge is reasonably flat, one of the favourite modes of transport for students is the bicycle; an estimated fifth of journeys in the city are made by bike, a figure enhanced by the fact that students are not permitted to hold car park permits except under special circumstances.

Notable locations

The University of Cambridge and its constituency campuses include many notable locations, some iconic, of historical, academic, religious, and cultural significance, including:

*

Bridge of Sighs, Cambridge

*

Cambridge University Botanic Garden

The Cambridge University Botanic Garden is a botanical garden located in Cambridge, England, associated with the university Department of Plant Sciences (formerly Botany School). It lies between Trumpington Road to the west, Bateman Street to ...

*

Church of St Mary the Great, Cambridge

*

Downing Site

The Downing Site is a major site of the University of Cambridge, located in the centre of the city of Cambridge, England, on Downing Street and Tennis Court Road, adjacent to Downing College. The Downing Site is the larger and newer of two ci ...

*

Fenner's

Fenner's is Cambridge University Cricket Club's ground.

History

Cambridge University Cricket Club had previously played at two grounds in Cambridge, the University Ground and Parker's Piece. In 1846, Francis Fenner leased a former cherry orchard ...

*

Goldie Boathouse

*

King's College Chapel, Cambridge

King's College Chapel is the chapel of King's College in the University of Cambridge. It is considered one of the finest examples of late Perpendicular Gothic English architecture and features the world's largest fan vault. The Chapel was bu ...

*

Lady Mitchell Hall

*

Mathematical Bridge

*

Nevile's Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

Nevile's Court is a court in Trinity College, Cambridge, England, created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile.Stourton, E. 2011, Trinity: A Portrait . Third Millennium Press Limited. Available Online a/ref>

The east side is dom ...

*

Sidgwick Site

The Sidgwick Site is one of the largest sites within the University of Cambridge, England.

Overview and history

The Sidgwick Site is located on the western side of Cambridge city centre, near the Backs. The site is north of Sidgwick Avenue an ...

*

St Bene't's Church

St Bene't's Church is a Church of England parish church in central Cambridge, England. Parts of the church, most notably the tower, are Anglo-Saxon, and it is the oldest church in Cambridgeshire as well as the oldest building in Cambridge.

Th ...

*

The Backs

The Backs is a picturesque area to the east of Queen's Road in the city of Cambridge, England, where several colleges of the University of Cambridge back on to the River Cam, their grounds covering both banks of the river.

National Trust chairm ...

*

Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge

Trinity College Chapel is the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge, a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Part of a complex of Grade I listed buildings at Trinity, it dates from the mid 16th century. It is an Anglican church in t ...

*

West Cambridge

West Cambridge is a university site to the west of Cambridge city centre in England. As part of the ''West Cambridge Master Plan'', several of the University of Cambridge's departments have relocated to the West Cambridge site from the centre ...

Organisation and administration

Cambridge is defined as a

collegiate university

A collegiate university is a university in which functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the C ...

, meaning that it is made up of self-governing and independent colleges, each with its own property and income. Most colleges bring together academics and students from a broad range of disciplines. Within each faculty, school, or department within the university, are academics from many differing colleges.

The faculties are responsible for ensuring that lectures are given, arranging seminars, performing research and determining the syllabi for teaching, all of which is overseen by the university's general board. Together with the central administration headed by the

Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

, they make up the University of Cambridge. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels by the university (the

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

), by the faculties (including faculty libraries such as the

Squire Law Library), and by individual colleges, all of which maintain a multi-discipline library generally designed for each college's respective undergraduates.

Legally, the university is an

exempt charity An exempt charity is an institution established in England and Wales for charitable purposes which is exempt from registration with, and oversight by, the Charity Commission for England and Wales.

Exempt charities are largely institutions of furth ...

and a common law

corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

with the corporate title The Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge.

Colleges

The colleges are self-governing institutions with their own endowments and property, each founded as components of the university. All students and most academics are attached to a college. The colleges' importance lies in the housing, welfare, social functions, and undergraduate teaching they provide. All faculties, departments, research centres, and laboratories belong to the university, which arranges lectures and awards degrees but undergraduates receive their overall academic supervision through small group teaching sessions often with just one student within the colleges (though in many cases students go to other colleges for supervision if the teaching fellows at their college do not specialise in a student's particular area of focus). Each college appoints its own teaching staff and

fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

s, both of whom are members of a university department. The colleges also decide which undergraduates to admit to the university, in accordance with university regulations.

Cambridge has 31 colleges, two of which,

Murray Edwards and

Newnham, admit women only. The other colleges are

mixed.

Darwin was the first college to admit both men and women while, beginning in 1972,

Churchill,

Clare, and

King's were the first previously all-male colleges to admit female undergraduates. In 1988,

Magdalene became the last all-male college to accept women. Clare Hall and Darwin admit only postgraduates, and

Hughes Hall,

St Edmund's, and

Wolfson admit only

mature (i.e., 21 years or older on date of

matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now ...

) students, encompassing both undergraduate and graduate students).

Lucy Cavendish, which was previously a women-only mature college, began admitting both men and women in 2021. All other colleges admit both undergraduate and postgraduate students with no age restrictions.

Colleges are not required to admit students in all subjects; some colleges choose not to offer subjects such as architecture, art history, or theology, but most offer close to the complete range of academic specialties and related courses. Some colleges maintain a relative strength and associated reputation for expertise in certain academic disciplines. For example,

Churchill has a reputation for its expertise and focus on the sciences and engineering, while others such as

St Catharine's aim for a balanced intake. Other colleges have more informal academic focus and even demonstrated ideological focus, such as

King's, which is known for its

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

political orientation, and

Robinson Robinson may refer to:

People and names

* Robinson (name)

Fictional characters

* Robinson Crusoe, the main character, and title of a novel by Daniel Defoe, published in 1719

Geography

* Robinson projection, a map projection used since the 1960 ...

and

Churchill, both of which have a reputation in

sustainability and

environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seeks ...

.

Costs to students for room and board vary considerably from college to college. Similarly, the investment in student education by each college at the university varies widely between the colleges.

There are several theological colleges, including

Westcott House,

Westminster College, and

Ridley Hall Theological College, that are members of the

Cambridge Theological Federation

The Cambridge Theological Federation (CTF) is an association of theological colleges, courses and houses based in Cambridge, England and founded in 1972. The federation offers several joint theological programmes of study open to students in membe ...

and only informally associated with the university.

The University of Cambridge's 31 colleges include:

#

Christ's

Christ's

#

Churchill

Churchill

#

Clare

Clare

#

Clare Hall

Clare Hall

#

Corpus Christi

Corpus Christi

#

Darwin

Darwin

#

Downing

Downing

#

Emmanuel

Emmanuel

#

Fitzwilliam

Fitzwilliam

#

Girton

Girton

#

Gonville & Caius

Gonville & Caius

#

Homerton

Homerton

#

Hughes Hall

Hughes Hall

#

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

#

King's

King's

#

Lucy Cavendish

Lucy Cavendish

#

Magdalene

Magdalene

#

Murray Edwards

Murray Edwards

#

Newnham

Newnham

#

Pembroke

Pembroke

#

Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite o ...

#

Queens'

Queens'

#

Robinson Robinson may refer to:

People and names

* Robinson (name)

Fictional characters

* Robinson Crusoe, the main character, and title of a novel by Daniel Defoe, published in 1719

Geography

* Robinson projection, a map projection used since the 1960 ...

#

Selwyn

Selwyn

#

Sidney Sussex

Sidney Sussex

#

St Catharine's

St Catharine's

#

St Edmund's

St Edmund's

#

St John's

St John's

#

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

#

Trinity Hall

Trinity Hall

#

Wolfson

Wolfson

Schools, faculties and departments

In addition to the 31 colleges, the university is made up of over 150 departments, faculties, schools, syndicates, and other institutions. Members of these are usually members of one of the colleges with responsibility for the entire academic programme of the university divided among them.

The university has a department dedicated to providing

continuing education, the

Institute of Continuing Education

The University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education (ICE) is a department of the University of Cambridge dedicated to providing continuing education programmes which allow students to obtain University of Cambridge qualifications at un ...

, which is based primarily in

Madingley Hall, a 16th-century manor house in

Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire to the ...

. Its award-bearing programmes range from undergraduate certificates through part-time master's degrees.

A school in the University of Cambridge is a broad administrative grouping of related faculties and other units. Each has an elected supervisory body known as a Council, composed of representatives of the various constituent bodies. The University of Cambridge maintains six schools:

* Arts and Humanities

* Biological Sciences

* Clinical Medicine

* Humanities and Social Sciences

* Physical Sciences

* Technology

Teaching and research at the university is organised by faculties. The faculties have different organisational substructures that partly reflect their history and partly the university's operational needs, which may include a number of departments and other institutions. A small number of bodies called Syndicates hold responsibility for teaching and research, including for the

University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate

University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES) is a non-teaching department of the University of Cambridge, which operates under the brand name Cambridge Assessment, and is part of Cambridge University Press & Assessment. It provi ...

, the

University Press

A university press is an academic publishing house specializing in monographs and scholarly journals. Most are nonprofit organizations and an integral component of a large research university. They publish work that has been reviewed by schola ...

, and the

University Library.

Central administration

Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor

The

Chancellor of the university is limitless term position that is mainly ceremonial and is held currently by

David Sainsbury, Baron Sainsbury of Turville

David John Sainsbury, Baron Sainsbury of Turville, , raeng.org.uk. Accessed 8 September 2022. (24 October 1940) is a British politician, businessman and philanthropist. From 1992 to 1997, he served as chairman of Sainsbury's, the supermarket c ...

, who succeeded the

Duke of Edinburgh following his retirement on his 90th birthday in June 2011. Lord Sainsbury was nominated by the nomination board.

The

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

took place on 14 and 15 October 2011

with Sainsbury taking 2,893 of the 5,888 votes cast, and winning on the election's first count.

The current Acting

Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

is

Anthony Freeling.

While the Chancellor's office is ceremonial, the Vice-Chancellor is the university's ''de facto'' principal administrative officer. The university's internal governance is carried out almost entirely by

Regent House augmented by some external representation from the Audit Committee and four external members of the

University's Council.

Senate and the Regent House

The university Senate consists of all holders of the

MA degree or higher degrees and is responsible for electing the Chancellor, the High Steward, and two members of the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

(until the

Cambridge University constituency was abolished in 1950). Prior to 1926, the university Senate was the university's governing body, fulfilling the functions that

Regent House provides today. Regent House is the university's governing body, a direct democracy comprising all resident senior members of the university and the colleges, together with the Chancellor, the

High Steward, the Deputy High Steward, and the Commissary. Public representatives of the Regent House are the two

Proctors, elected to serve for one year upon nomination by the Colleges.

Council and General Board

Although the

University Council is the university's principal executive and policy-making body, the Council reports to, and is held accountable by,

Regent House through a variety of checks and balances. The council is obliged to advise Regent House on matters of general concern to the university. It does this by publishing notices to the ''

Cambridge University Reporter

The ''Cambridge University Reporter'', founded in 1870, is the official journal of record of the University of Cambridge, England.

Overview

The ''Cambridge University Reporter'' appears within the University and online every Wednesday during ...

'', the university's official journal. Since January 2005, the council's membership has included two external members. In March 2008, Regent House voted to increase from two to four the number of external members on the council. and this was approved by Her Majesty the Queen in July 2008.

The General Board of the Faculties is responsible for the university's academic and educational policies and is accountable to the council for its management of these affairs.

Faculty Boards are accountable to the General Board; other Boards and Syndicates are accountable either to the General Board or to the council. Under this organizational structure, the university's various arms are kept under the supervision of both the central administration and Regent House.

Finances

Benefactions and fundraising

In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2019, the central university, excluding colleges, reported total income of £2.192 billion, of which £592.4 million was from research grants and contracts.

In the decade prior to 2019, the University of Cambridge reported an average of £271m a year in philanthropic donations.

The

Stormzy Scholarship for Black UK Students covers tuition costs for two students and maintenance grants for up to four years.

In 2000,

Bill Gates

William Henry Gates III (born October 28, 1955) is an American business magnate and philanthropist. He is a co-founder of Microsoft, along with his late childhood friend Paul Allen. During his career at Microsoft, Gates held the positions ...

of

Microsoft

Microsoft Corporation is an American multinational technology corporation producing computer software, consumer electronics, personal computers, and related services headquartered at the Microsoft Redmond campus located in Redmond, Washin ...

donated US$210 million through the

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), a merging of the William H. Gates Foundation and the Gates Learning Foundation, is an American private foundation founded by Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates. Based in Seattle, Washington, it was ...

to endow

Gates Scholarships for students from outside the UK pursuing post-graduate study at Cambridge.

In October 2021, the university suspended its £400m collaboration with the

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at t ...

, citing allegation that the UAE was involved in illegal hacking using the

NSO Group's

Pegasus software. UAE also was behind the leak of over 50,000 phone numbers, including hundreds belonging to British citizens. The university's outgoing Vice-Chancellor,

Stephen Toope

Stephen John Toope (born February 14, 1958) is a Canadian legal scholar, academic administrator and a scholar specializing in human rights, public international law and international relations.

In April 2013 he announced he was stepping down ...

said the decision to suspend its collaboration with UAE also was a result of additional revelations about UAE's Pegasus software hacking.

Bonds

The University of Cambridge borrowed £350 million by issuing a 40-year security bond in October 2012.

[Cambridge university issues its first £350m bond](_blank)

L. Tidy, The Cambridge Student, News, 11 October 2012 Its interest rate is about 0.6 percent higher than a British government 40-year bond. Vice-Chancellor

Leszek Borysiewicz

Sir Leszek Krzysztof Borysiewicz (born 13 April 1951) is a British professor, immunologist and scientific administrator. He served as the 345th Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, his term of office (a maximum of seven years) sta ...

praised the bond issuance. In a 2010 report, the

Russell Group

The Russell Group is a self-selected association of twenty-four public research universities in the United Kingdom. The group is headquartered in Cambridge and was established in 1994 to represent its members' interests, principally to governmen ...

of 20 leading universities concluded that higher education could be financed by bond issuance.

Affiliations and memberships

The University of Cambridge is a member of the

Russell Group

The Russell Group is a self-selected association of twenty-four public research universities in the United Kingdom. The group is headquartered in Cambridge and was established in 1994 to represent its members' interests, principally to governmen ...

of research-led

British universities, the

G5, the

League of European Research Universities

The League of European Research Universities (LERU) is a consortium of European research universities.

History and overview

The League of European Research Universities (LERU) is an association of research-intensive universities. Founded in 2002 ...

, and the

International Alliance of Research Universities