California And The Railroads on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked

California's symbolic and tangible connection to the rest of the country was fused at

California's symbolic and tangible connection to the rest of the country was fused at  "Transportation determines the flow of population," declared J. D. Spreckels, one of California's early railroad entrepreneurs, just after the dawn of the twentieth century. "Before you can hope to get people to live anywhere...you must first of all show them that they can get there quickly, comfortably and, above all, cheaply." Among Spreckels' many accomplishments was the formation of the

"Transportation determines the flow of population," declared J. D. Spreckels, one of California's early railroad entrepreneurs, just after the dawn of the twentieth century. "Before you can hope to get people to live anywhere...you must first of all show them that they can get there quickly, comfortably and, above all, cheaply." Among Spreckels' many accomplishments was the formation of the  As with the Comstock mining securities boom of the 1870s, Los Angeles' land boom attracted an unscrupulous element that often sold interest in properties whose titles were not properly recorded, or in tracts that did not even exist. Major advertising campaigns by the SP, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and other major carriers of the day not only helped transform southern California into a major tourist attraction but generated intense interest in exploiting the area's agricultural potential. Word of the abundant work opportunities, high wages, and the temperate and healthful California climate spread throughout the

As with the Comstock mining securities boom of the 1870s, Los Angeles' land boom attracted an unscrupulous element that often sold interest in properties whose titles were not properly recorded, or in tracts that did not even exist. Major advertising campaigns by the SP, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and other major carriers of the day not only helped transform southern California into a major tourist attraction but generated intense interest in exploiting the area's agricultural potential. Word of the abundant work opportunities, high wages, and the temperate and healthful California climate spread throughout the

Even today, California is well known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild

Even today, California is well known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild

With the expansion of agriculture interests throughout the state (along with new rail lines to carry the goods to faraway markets), new communities were founded and existing towns expanded. Agrarian successes led to the establishment of post offices, schools, churches, mercantile outlets, and ancillary industries such as packing houses. The discovery of ''brea'', more commonly referred to as

With the expansion of agriculture interests throughout the state (along with new rail lines to carry the goods to faraway markets), new communities were founded and existing towns expanded. Agrarian successes led to the establishment of post offices, schools, churches, mercantile outlets, and ancillary industries such as packing houses. The discovery of ''brea'', more commonly referred to as

As has been previously discussed, the railroads were among the first to promote California tourism as early as the 1870s, both as a means to increase ridership and to create new markets for the freight hauling business in the areas they served. Some sixty years later, the Santa Fe would lead a resurgence in leisure travel to and along the west coast aboard such "name" trains as the ''

As has been previously discussed, the railroads were among the first to promote California tourism as early as the 1870s, both as a means to increase ridership and to create new markets for the freight hauling business in the areas they served. Some sixty years later, the Santa Fe would lead a resurgence in leisure travel to and along the west coast aboard such "name" trains as the ''

In 1901,

In 1901,  The Northern California railroad barons also effectively slowed San Diego's development in the early 20th century. San Diego had a natural harbor and many thought that it would become a major port on the west coast. However, San Francisco was strongly opposed to this as San Diego's development would hurt their trade.

The Northern California railroad barons also effectively slowed San Diego's development in the early 20th century. San Diego had a natural harbor and many thought that it would become a major port on the west coast. However, San Francisco was strongly opposed to this as San Diego's development would hurt their trade.

Passenger rail in California during the early 20th Century was dominated by private companies.

Passenger rail in California during the early 20th Century was dominated by private companies.

One urban system that survived the streetcar decline was the

One urban system that survived the streetcar decline was the  Environmental and traffic concerns beginning in the 1970s led to a resurgence in urban passenger rail, specifically the construction light rail networks.

Environmental and traffic concerns beginning in the 1970s led to a resurgence in urban passenger rail, specifically the construction light rail networks.

When

When

The

The

One service spared from discontinuance was the Southern Pacific

One service spared from discontinuance was the Southern Pacific  The North San Diego County Transit Development Board was created in 1975 to consolidate and improve transit in northern San Diego County. Planning began for a San Diego–Oceanside commuter rail line, then called Coast Express Rail, in 1982. The Board established the San Diego Northern Railway Corporation (SDNR) — a nonprofit operating subsidiary — in 1994, and purchased the of the Surf Line within San Diego County plus the Escondido Branch from the Santa Fe Railway that year.

By the 90s, growth in the Tri-Valley and the middle Central Valley had led to congestion on local freeways while providing little access to public transit. In May 1997, the Altamont Commuter Express Joint Powers Authority was formed by the

The North San Diego County Transit Development Board was created in 1975 to consolidate and improve transit in northern San Diego County. Planning began for a San Diego–Oceanside commuter rail line, then called Coast Express Rail, in 1982. The Board established the San Diego Northern Railway Corporation (SDNR) — a nonprofit operating subsidiary — in 1994, and purchased the of the Surf Line within San Diego County plus the Escondido Branch from the Santa Fe Railway that year.

By the 90s, growth in the Tri-Valley and the middle Central Valley had led to congestion on local freeways while providing little access to public transit. In May 1997, the Altamont Commuter Express Joint Powers Authority was formed by the

Railways companies, and thus routes, were largely consolidated under a few

Railways companies, and thus routes, were largely consolidated under a few

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed to the state's social, political, and economic development. When California was admitted as a state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

to the United States in 1850, and for nearly two decades thereafter, it was in many ways isolated, an outpost on the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

, until the first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

was completed in 1869.

Passenger rail transportation declined in the early- and mid-20th Century with the rise of the state's car culture and road system. It has since undergone something of a renaissance, with the introduction of services such as Metrolink, Coaster, Caltrain

Caltrain (reporting mark JPBX) is a California commuter rail line serving the San Francisco Peninsula and Santa Clara Valley (Silicon Valley). The southern terminus is in San Jose at Tamien station with weekday rush hour service running as fa ...

, Amtrak California

Amtrak California is a brand name used by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) Division of Rail for three state-supported Amtrak commuter rail routes in Californiathe ''Capitol Corridor'', the ''Pacific Surfliner'', and the ...

, and others. On November 4, 2008, the People of California passed Proposition 1A, which helped provide financing for a high-speed rail line.

19th century

Background

The early Forty-Niners of theCalifornia Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

wishing to come to California were faced with limited options. From the East Coast, for example, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take five to eight months, and cover some 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km). An alternative route was to sail to the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

, to take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle

A jungle is land covered with dense forest and tangled vegetation, usually in tropical climates. Application of the term has varied greatly during the past recent century.

Etymology

The word ''jungle'' originates from the Sanskrit word ''ja� ...

, and then on the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

side, to wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco.Brands, H. W. (2003), pp. 75-85. Another route across Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

was developed in 1851; it was not as popular as the Panama option. (''see'' ) During the 1850s the voy:Ruta de Transito through Nicaragua was another option. Eventually, most gold-seekers took the overland route across the continental United States, particularly along the California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

.Rawls and Orsi, (1999) p. 5. Each of these routes had its own deadly hazards, from typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

to cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

or Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

attack.

Transcontinental links

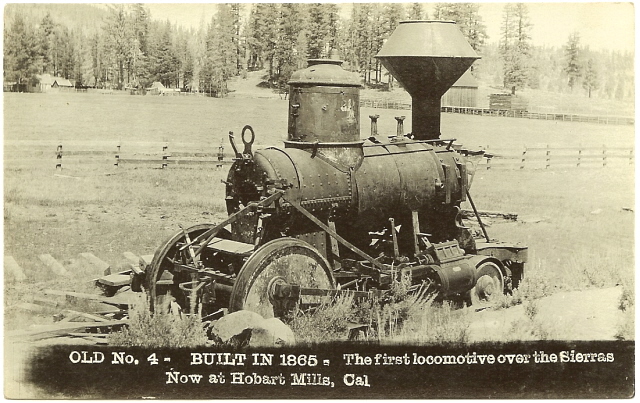

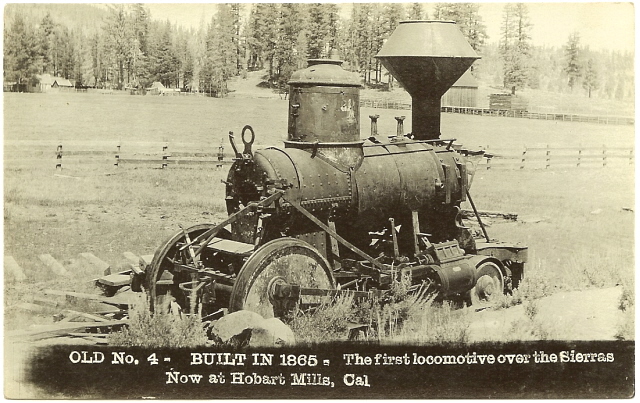

The very first "inter-oceanic" railroad that affected California was built in 1855 across the Isthmus of Panama, thePanama Railway

The Panama Canal Railway ( es, Ferrocarril de Panamá) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches across the Isthmus of Panama from Colón (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near ...

. The Panama Railway reduced the time needed to cross the Isthmus from a week of difficult and dangerous travel to a day of relative comfort. The building of the Panama Railroad, in combination with the increasing use of steamships

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

(instead of sailing ships) meant that travel to and from California via Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

was the primary method used by people who could afford to do so, and was used for valuable cargo, such as the gold being shipped from California to the East Coast.

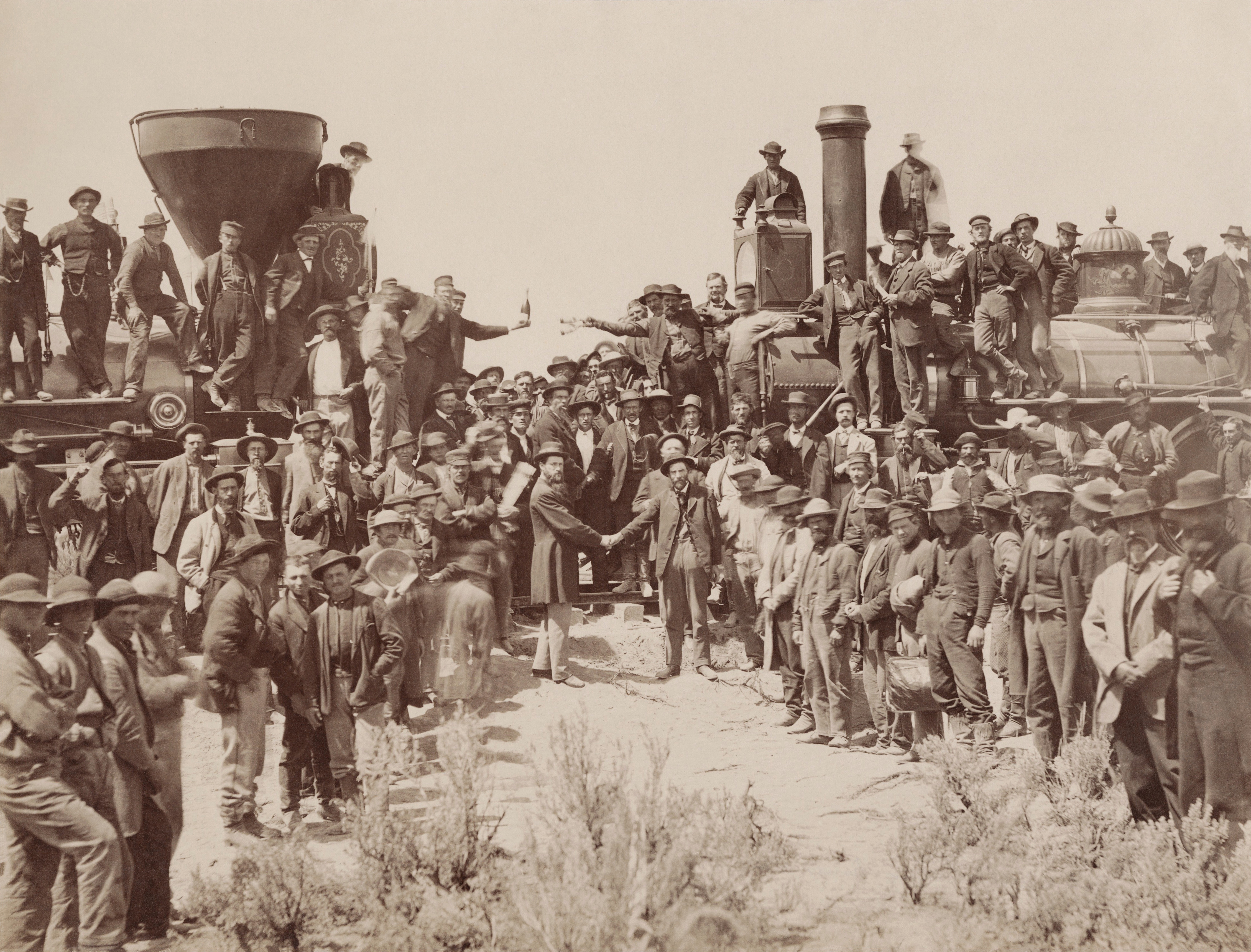

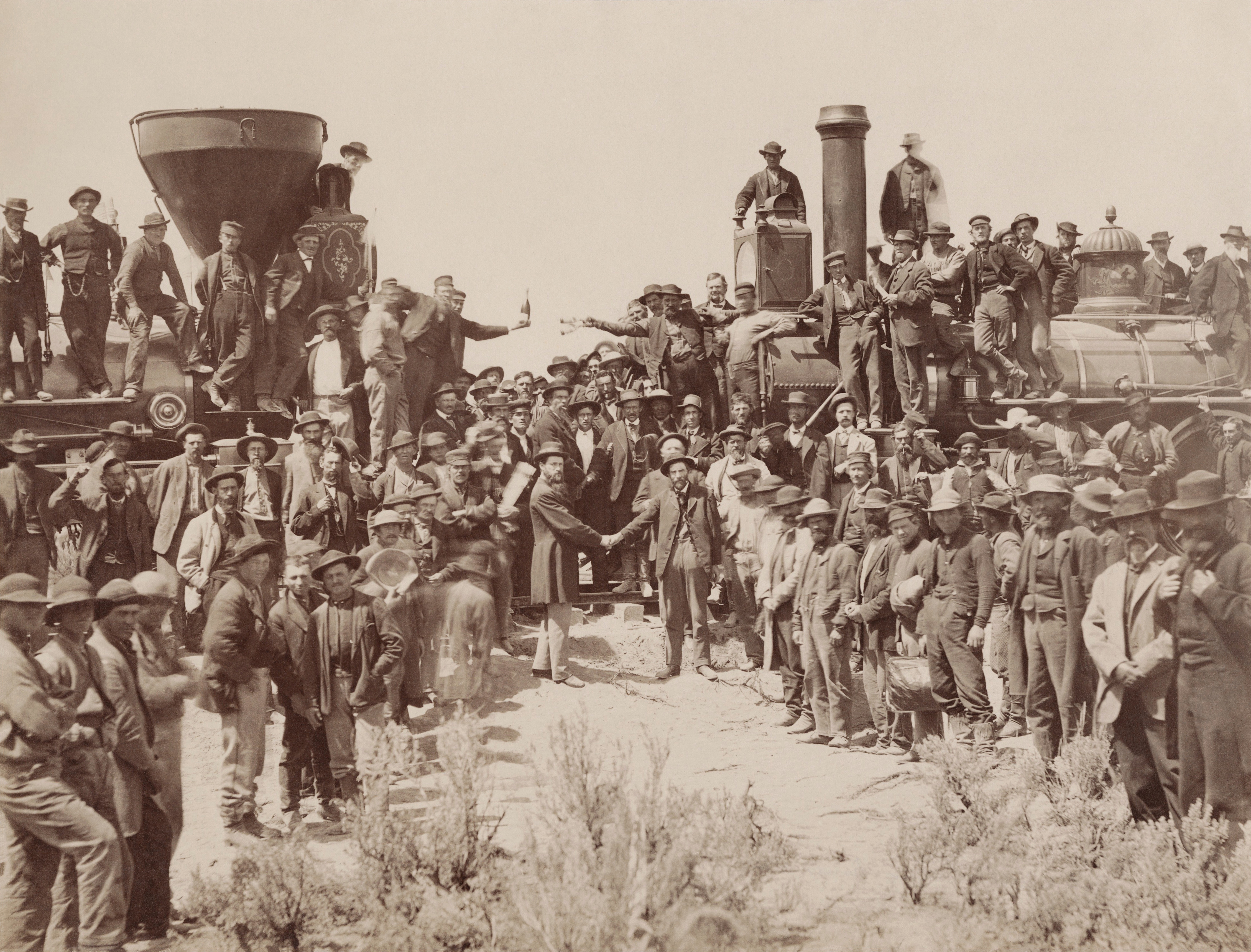

California's symbolic and tangible connection to the rest of the country was fused at

California's symbolic and tangible connection to the rest of the country was fused at Promontory Summit, Utah

Promontory is an area of high ground in Box Elder County, Utah, United States, 32 mi (51 km) west of Brigham City and 66 mi (106 km) northwest of Salt Lake City. Rising to an elevation of 4,902 feet (1,494 m) above s ...

, as the "last spike" was driven to join the tracks of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

s, thereby completing the first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

on May 10, 1869 (before that time, only a few local rail lines operated in the State, the first being the Sacramento Valley Railroad). The 1,600 mile (2,575-kilometer) trip from Omaha, Nebraska, would now take mere days. The Wild West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

was quickly transformed from a lawless, agrarian frontier to what would become an urbanized, industrialized economic and political powerhouse. Of perhaps greater significance is the unbridled economic growth that was spurred on by the sheer diversity of opportunities available in the region.

The four years following the Golden Spike

The golden spike (also known as The Last Spike) is the ceremonial 17.6- karat gold final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific Railroad ...

ceremony saw the length of track in the U.S. double to over 70,000 miles (nearly 113,000 kilometers). By around the start of the 20th century, the completion of four subsequent transcontinental routes in the United States and one in Canada would provide not only additional pathways to the Pacific Ocean, but would forge ties to all of the economically important areas between the coasts as well. Virtually the entire country was accessible by rail, making a national economy possible for the first time. And while federal financial assistance (in the form of land grants and guaranteed low-interest loans, a well-established government policy) was vital to the railroads' expansion across North America, this support accounted for less than eight percent (8%) of the total length of rails laid; private investment was responsible for the vast majority of railroad construction.

As rail lines pushed further and further into the wilderness, they opened up huge areas. The railroads helped establish towns and settlements, paved the way to abundant mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

deposits and fertile tracts of pastures and farmland, and created new markets for eastern goods. It is estimated that by the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, rail companies nationwide remunerated to the government over $1 billion dollars, more than eight times the original value of the lands granted. The principal commodity transported across the rails to California was people: by reducing the cross-country travel time to as little as six days, men with westward ambitions were no longer forced to leave their families behind. The railroads would, in time, provide equally important linkages to move the inhabitants throughout the state, interconnecting its blossoming communities.

"Transportation determines the flow of population," declared J. D. Spreckels, one of California's early railroad entrepreneurs, just after the dawn of the twentieth century. "Before you can hope to get people to live anywhere...you must first of all show them that they can get there quickly, comfortably and, above all, cheaply." Among Spreckels' many accomplishments was the formation of the

"Transportation determines the flow of population," declared J. D. Spreckels, one of California's early railroad entrepreneurs, just after the dawn of the twentieth century. "Before you can hope to get people to live anywhere...you must first of all show them that they can get there quickly, comfortably and, above all, cheaply." Among Spreckels' many accomplishments was the formation of the San Diego Electric Railway

The San Diego Electric Railway (SDERy) was a mass transit system in Southern California, United States, using 600 volt DC streetcars and (in later years) buses.

The SDERy was established by sugar heir and land developer John D. Spreckels in ...

in 1892, which radiated out from downtown to points north, south, and east and helped urbanize San Diego. Henry Huntington, the nephew of Central Pacific founder Collis P. Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker) who invested i ...

, would develop his Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway syst ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

and Orange Counties with much the same result. Spreckels' greatest challenge would be to provide San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

with its own direct transcontinental rail link in the form of the San Diego and Arizona Railway

The San Diego and Arizona Railway was a Short-line railroad, short line United States, U.S. railroad founded by entrepreneur John D. Spreckels, and dubbed "The Impossible Railroad" by engineers of its day due to the immense logistical challeng ...

(completed in November 1919), a feat that nearly cost the sugar heir his life. The Central Pacific Railroad, in effect, initiated the trend by offering settlement incentives in the form of low fares, and by placing sections of its government-granted lands up for sale to pioneers.

When the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, and ...

charted its own solo course across the continent in 1885 it chose Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

as its western terminus

Terminus may refer to:

* Bus terminus, a bus station serving as an end destination

* Terminal train station or terminus, a railway station serving as an end destination

Geography

*Terminus, the unofficial original name of Atlanta, Georgia, United ...

, and in doing so fractured the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

's near total monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

on rail transportation within the state. The original purpose of this new line was to augment the route to San Diego, established three years prior as part of a joint venture with the California Southern Railroad

The California Southern Railroad was a subsidiary railroad of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (Santa Fe) in Southern California. It was organized July 10, 1880, and chartered on October 23, 1880, to build a rail connection between wh ...

, but the Santa Fe would subsequently be forced to all but abandon these inland tracks through the Temecula Canyon (due to constant washouts) and construct its Surf Line along the coast to maintain its exclusive ties to Los Angeles. Santa Fe's entry into Southern California resulted in widespread economic growth and ignited a fervent rate war with the Southern Pacific, or "Espee" as the road was often referred to; it also led to Los Angeles' well-documented real estate "Boom of the Eighties". The Santa Fe Route led the way in passenger rate reductions (often referred to as "colonist fares") by, within a period of five months, lowering the price of a ticket from Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the List of United States cities by populat ...

to Los Angeles from $125 to $15, and, on March 6, 1887 to a single dollar.Duke and Kistler, p. 32 The Southern Pacific soon followed suit and the level of real estate speculation reached a new high, with "boom towns" springing up literally overnight. Free, daily railroad-sponsored excursions (complete with lunch and live entertainment) enticed overeager potential buyers to visit the many undeveloped properties firsthand and invest in the land.

As with the Comstock mining securities boom of the 1870s, Los Angeles' land boom attracted an unscrupulous element that often sold interest in properties whose titles were not properly recorded, or in tracts that did not even exist. Major advertising campaigns by the SP, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and other major carriers of the day not only helped transform southern California into a major tourist attraction but generated intense interest in exploiting the area's agricultural potential. Word of the abundant work opportunities, high wages, and the temperate and healthful California climate spread throughout the

As with the Comstock mining securities boom of the 1870s, Los Angeles' land boom attracted an unscrupulous element that often sold interest in properties whose titles were not properly recorded, or in tracts that did not even exist. Major advertising campaigns by the SP, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and other major carriers of the day not only helped transform southern California into a major tourist attraction but generated intense interest in exploiting the area's agricultural potential. Word of the abundant work opportunities, high wages, and the temperate and healthful California climate spread throughout the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

, and led to an exodus from such states as Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, and Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

; although the real estate bubble "burst" in 1889 and most investors lost their all, the Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most populous urban ...

landscape was forever transformed by the many towns, farms, and citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is native to ...

groves left in the wake of this event.

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

s James Rawls and Walton Bean have speculated that were it not for the discovery of gold in 1848, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

might have been granted statehood ahead of California, and therefore the first Pacific Railroad might have been built to that state, or at least been born to a more benevolent group of founding fathers. This speculation lacks support, however, when one considers that a significant hide and tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton fat. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, includ ...

trade between California and the eastern seaports was already well-established, that the federal government had long planned for the acquisition of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

as a western port, and that suspicions regarding England's intentions towards potentially extending their holdings in the region southward into California would almost certainly have forced the government to embark on the same course of action.

While the completion of the first transcontinental railroad was a major milestone in America's history, it would also foster the birth of a railroad empire that would have a dominant influence over California's evolution for years to come. Despite all of the shortcomings, in the end the State gained unprecedented benefits from its associations with the railroad companies.

Agriculture

Even today, California is well known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild

Even today, California is well known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild berries

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit, although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples are strawberries, ras ...

or grew on small bushes. Spanish missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

brought fruit seeds over from Europe, many of which had been introduced to the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

from Asia following earlier expeditions to the continent; orange, grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus '' Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began perhaps 8,000 years a ...

, apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancest ...

, peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, n ...

, pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in late summer into October. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the Family (biology), family Rosacea ...

, and fig

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

seeds were among the most prolific of the imports.

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel ( es, Misión de San Gabriel Arcángel) is a Californian mission and historic landmark in San Gabriel, California. It was founded by Spaniards of the Franciscan order on "The Feast of the Birth of Mary," September ...

, fourth in the Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

chain, was founded in 1771 near what would one day be the City of Los Angeles. Thirty-three years later the mission would unknowingly witness the origin of the California citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is native to ...

industry with the planting of the region's first significant orchard, though the commercial potential of citrus would not be realized until 1841. Several small carloads of California crops were shipped eastward via the new transcontinental route almost immediately after its completion, using a special type of ventilated boxcar

A boxcar is the North American (AAR) term for a railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simplest freight car design, is considered one of the most versatile since it can carry most ...

modified specifically for this purpose. The advent of the iced refrigerator car

A refrigerator car (or "reefer") is a refrigerated boxcar (U.S.), a piece of railroad rolling stock designed to carry perishable freight at specific temperatures. Refrigerator cars differ from simple insulated boxcars and ventilated boxcars (co ...

or "reefer" led to increases in both the amount of product carried and in the distances traveled.

For years, the overall scarcity of oranges in particular led to the general perception that they were suitable only for holiday table decoration or as indulgences for the affluent. During the 1870s, however, hybridization

Hybridization (or hybridisation) may refer to:

*Hybridization (biology), the process of combining different varieties of organisms to create a hybrid

*Orbital hybridization, in chemistry, the mixing of atomic orbitals into new hybrid orbitals

*Nu ...

of California oranges led to the creation of several flavorful strains, chief among these the Navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, altho ...

and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

varieties, whose development allowed for year-round cultivation of the fruit. Substantial foreign (out-of-state) markets for California citrus would come into full stature by 1890, initiating a period referred to as the ''Orange Era''.

As the market for agricultural goods outside the state's boundaries increased, the Santa Fe developed a massive fleet of refrigerator dispatch cars, and in 1906 the Southern Pacific joined with the Union Pacific Railroad to create the Pacific Fruit Express

Pacific Fruit Express was an American railroad refrigerator car leasing company that at one point was the largest refrigerator car operator in the world.

History

The company was founded on December 7, 1906, as a joint venture between the Union P ...

. Fully half the farm products produced in California could now be exported throughout the country, with western railroads carrying virtually all of the perishable fruit traffic. The western states of California, Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

would dominate U.S. agricultural production by the coming of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

; once such diverse and high-demand crops as wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, sugar beet

A sugar beet is a plant whose root contains a high concentration of sucrose and which is grown commercially for sugar production. In plant breeding, it is known as the Altissima cultivar group of the common beet ('' Beta vulgaris''). Together ...

s, olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ' ...

s, and lettuce

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of food, ...

were cultivated, California would become known as the nation's "produce basket."

Oil boom

tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bi ...

, in Southern California would lead to an oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

boom in the early twentieth century. Railroad companies soon discovered that shipping wooden barrels loaded with oil via boxcars was not cost-effective, and developed steel cylindrical tank car

A tank car ( International Union of Railways (UIC): tank wagon) is a type of railroad car (UIC: railway car) or rolling stock designed to transport liquid and gaseous commodities.

History

Timeline

The following major events occurred in ...

s capable of transporting bulk liquids

Bulk cargo is commodity cargo that is transported unpackaged in large quantities.

Description

Bulk cargo refers to material in either liquid or granular, particulate form, as a mass of relatively small solids, such as petroleum/ crude oi ...

virtually anywhere. By 1915, the transportation of petroleum products had become a lucrative endeavor for western railroads.

Most oil tank cars would remain in revenue service for decades until the "Black Bonanza" had run its course. The Southern Pacific is credited with being the first western railroad to experiment in 1879 with the use of oil in its locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the ...

s as a fuel source in lieu of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

(with substantial technical assistance from the Union Oil Company

Union Oil Company of California, and its holding company Unocal Corporation, together known as Unocal was a major petroleum explorer and marketer in the late 19th century, through the 20th century, and into the early 21st century. It was headqu ...

, one of the SP's biggest accounts). By 1895, oil-burning locomotives were in operation on a number of Southern Pacific routes, and on the competing California Southern and Great Northern Railway as well. This innovation not only allowed the SP (and other railroads that soon followed their example) to benefit from the use of this abundant and economically viable fuel source, but to create new markets by capitalizing on the burgeoning petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

industry. The conversion from coal to oil also help solved the Southern Pacific's problem of intense smoke in the tunnels of the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primar ...

. Thanks to the railroads, California was once again thrust into the limelight

Limelight (also known as Drummond light or calcium light)James R. Smith (2004). ''San Francisco's Lost Landmarks'', Quill Driver Books. is a type of stage lighting once used in theatres and music halls. An intense illumination is created whe ...

.

Tourism

As has been previously discussed, the railroads were among the first to promote California tourism as early as the 1870s, both as a means to increase ridership and to create new markets for the freight hauling business in the areas they served. Some sixty years later, the Santa Fe would lead a resurgence in leisure travel to and along the west coast aboard such "name" trains as the ''

As has been previously discussed, the railroads were among the first to promote California tourism as early as the 1870s, both as a means to increase ridership and to create new markets for the freight hauling business in the areas they served. Some sixty years later, the Santa Fe would lead a resurgence in leisure travel to and along the west coast aboard such "name" trains as the ''Chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the bo ...

'' and later the ''Super Chief

The ''Super Chief'' was one of the named passenger trains and the flagship of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The streamliner claimed to be "The Train of the Stars" because of the various celebrities it carried between Chicago, Ill ...

''; the Southern Pacific would soon follow suit with their '' Golden State'' and ''Overland Flyer

The ''Overland Limited'' (also known at various times as the ''Overland Flyer'', ''San Francisco Overland Limited'', ''San Francisco Overland'' and often simply as the ''Overland'') was an American named passenger train which for much of its histo ...

'' trains, and the Union Pacific with its ''City of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

'' and ''City of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

''. The immense popularity of Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the United States government. She de ...

's 1884 novel ''Ramona

''Ramona'' is a 1884 American novel written by Helen Hunt Jackson. Set in Southern California after the Mexican–American War, it portrays the life of a mixed-race Scottish– Native American orphan girl, who suffers racial discrimination and ...

'' in particular fueled a surge in tourism, which happened to coincide with the opening of SP's Southern California lines.

The Santa Fé embraced the aura of the American Southwest in its advertising campaigns as well as its operations. The AT&SF routes and the high level of service provided thereon became popular with stars of the film industry in the thirties, forties and fifties, both building on and adding to the Hollywood mystique. The "golden age" of railroading would eventually end as travel by automobile and airplane became more cost-effective, and popular.

Corruption and scandal

In 1901,

In 1901, Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of Sa ...

vilified the Southern Pacific for its monopolistic practices in his acclaimed novel '' The Octopus: A Story of California''; John Moody's 1919 work ''The Railroad Builders: A Chronicle of the Welding of the State'' referred to "the American railroad problem" wherein the men who rode the iron horse were characterized as "monsters" that too often suppressed government reform and economic growth through political chicanery and corrupt business practices.

While it is true that much of the traveling public would have been unable to make the trip to California's sunny climate were it not for the fleet, relatively safe, and affordable trains of the western railroads, it is also true that those companies in effect preyed on those same settlers once they arrived at the end of the line. For instance, while the railroads provided much-needed transportation routes to out-of-state markets for locally produced raw materials and avenues of the import for eastern goods, there were numerous instances of rate fixing schemes among the various carriers, the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific included. Opposition to the railroads began early in Southern California's history due to the questionable practices of The Big Four in conducting the business of the Central (later Southern) Pacific. The Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

(and later the Southern Pacific) maintained and operated whole fleets of ferry boats that connected Oakland with San Francisco by water. Early on, the Central Pacific gained control of the existing ferry lines for the purpose of linking the northern rail lines with those from the south and east; during the late 1860s the company purchased nearly every bayside plot in Oakland, creating what author and historian Oscar Lewis described as a "wall around the waterfront" that put the town's fate squarely in the hands of the corporation. Competitors for ferry passengers or dock space were ruthlessly run out of business, and not even stage coach lines could escape the group's notice, or wrath.

The Northern California railroad barons also effectively slowed San Diego's development in the early 20th century. San Diego had a natural harbor and many thought that it would become a major port on the west coast. However, San Francisco was strongly opposed to this as San Diego's development would hurt their trade.

The Northern California railroad barons also effectively slowed San Diego's development in the early 20th century. San Diego had a natural harbor and many thought that it would become a major port on the west coast. However, San Francisco was strongly opposed to this as San Diego's development would hurt their trade. Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

, the manager of Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

was quoted as saying: “I would not take the road to San Diego as a gift. We would blot San Diego out of existence if we could, but as we can do that we shall keep it back as long as we can.” Instead, the Central Pacific only extended their rail route into Los Angeles."

Competition between carriers for rail routes was fierce as well, and unscrupulous means were often used to gain any advantage over one another. Santa Fe work crews engaged in sabotage to slow the progress of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the United ...

through the Rockies as the two fought their way toward the Coast; the Santa Fe (in conjunction with the California Southern) would win the race in establishing its connection to Bakersfield

Bakersfield is a city in Kern County, California, United States. It is the county seat and largest city of Kern County. The city covers about near the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley and the Central Valley region. Bakersfield's pop ...

in 1883. Some eleven years earlier, the Southern Pacific essentially blackmailed the then-fledgling City of Los Angeles into paying a hefty subsidy to ensure that the railroad’s north-south line would pass through town; in 1878, the company would be rebuffed in its attempts to extend its Anaheim

Anaheim ( ) is a city in northern Orange County, California, part of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. As of the 2020 United States Census, the city had a population of 346,824, making it the most populous city in Orange County, the 10th-most ...

branch southward to San Diego through Orange County's Irvine Ranch

The Irvine Company LLC is an American private company focused on real estate development. It is headquartered in Newport Beach, California, with a large portion of its operations centered in and around Irvine, California, a planned city of more ...

without securing the permission of James Irvine Sr., a longtime rival of Collis Huntington. The Southern Pacific would similarly block the westward progress of the Santa Fe (known to some as the People's Railroad) until September 1882, when a group of enraged citizens ultimately forced the railroad's management to relent. Numerous accounts of similar "frog war

A frog war occurs when one private railway company attempts to cross the tracks of another, and this results in hostilities between the two railways. It is named after the frog, the piece of track that allows the two tracks to join or cross and ...

s" and other such tactics have been recorded throughout California's railroad history.

Perhaps the most notorious examples of impropriety on the part of the railroads surround the process of land acquisition and sales. Since the federal government granted to the companies alternate tracts of land that ran along the tracks they had laid, it was generally assumed that the land would in turn be sold at its fair market value at the time the land was subdivided; circulars distributed by the SP (which was at the time a holding company formed by the Central Pacific Railroad) certainly implied as much. However, at least some of the tracts were put on the market only after considerable time had passed, and the land improved well beyond its raw state.

Families faced with asking prices of ten times or more of the initial value more often than not had no choice but to vacate their homes and farms, in the process losing everything they worked for; often it turned out to be a railroad employee who had purchased the property in question. A group of immigrant San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven ...

farmers formed the Settlers' League in order to challenge the Southern Pacific's actions in court, but after all of the lawsuits were decided in the favor of the railroads, one group decided to take matters into their own hands. What resulted was the infamous Battle at Mussel Slough, in which armed settlers clashed with railroad employees and law enforcement officers engaged in eviction proceedings. Six people were killed in the ensuing gunfight. The Southern Pacific would emerge from the tragedy as the prime target of journalists such as William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, ambitious politicians, and crusade groups for decades to follow. Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Sen ...

's term as Governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constitution of California, t ...

(while serving as president of Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

and later Southern Pacific) enhanced the corporation's political clout, but simultaneously further increased its notoriety as well.

Regulation

Public response to the corruption that arose from California's economic "explosion" led to the enactment of numerous reform and regulation measures, many of which coincided with the ascendancy of thePopulist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

and Progressive movements. Early examples of railroad regulation include Granger

Granger may refer to:

People

*Granger (name)

*Hermione Granger, a fictional character in Harry Potter

United States

* Granger, Indiana

* Granger, Iowa

* Granger, Minnesota

* Granger, Missouri

* Granger, New York

* Granger, Ohio

* Granger, Te ...

case decisions in the 1870s, and the creation of the first (albeit ineffective) Railroad Commission via amendment of the State's Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

of 1879, forerunner of today's California Public Utilities Commission

The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC or PUC) is a regulatory agency that regulates privately owned public utilities in the state of California, including electric power, telecommunications, natural gas and water companies. In addition ...

. In 1886, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Santa Clara County

Santa Clara County, officially the County of Santa Clara, is the sixth-most populous county in the U.S. state of California, with a population of 1,936,259, as of the 2020 census. Santa Clara County and neighboring San Benito County together ...

in ''Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad

''Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company'', 118 U.S. 394 (1886), is a corporate law case of the United States Supreme Court concerning taxation of railroad properties. The case is most notable for a headnote stating that the Equa ...

.'' The documents of the Court decision included a statement that a corporation henceforth could be considered an American citizen, with all the associated immunities and privileges (except the right to vote). The document phrasing has long made it difficult for states to pass legislation that could make corporations accountable to the people. The Stetson-Eshelman Act of 1911 provided for the fixing of shipping rates by state legislatures. In 1911, California's new Progressive government established the second Railroad Commission, more effective and less corrupted than the first one.

20th century

Buses replace streetcars and interurbans

Passenger rail in California during the early 20th Century was dominated by private companies.

Passenger rail in California during the early 20th Century was dominated by private companies. Interurban railway

The Interurban (or radial railway in Europe and Canada) is a type of electric railway, with streetcar-like electric self-propelled rail cars which run within and between cities or towns. They were very prevalent in North America between 1900 a ...

s gained popularity in the early part of the century as a means of medium-distance travel, usually as components of real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

speculation schemes. The Pacific Electric Railway Company

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

Red Car Lines was the largest electric railway system in the world by the 1920s, with over of tracks and 2,160 daily services across Los Angeles and Orange Counties. The Sacramento Northern Railway

The Sacramento Northern Railway (reporting mark SN) was a electric interurban railway that connected Chico in northern California with Oakland via the California capital, Sacramento. In its operation it ran directly on the streets of Oaklan ...

operated the world's longest single electric interurban service between Oakland and Chico. These and other services were largely abandoned in the 1940s and 50s as ridership declined and equipment fell into disrepair.

Local services were mostly controlled by a few primary operators. The San Diego Electric Railway

The San Diego Electric Railway (SDERy) was a mass transit system in Southern California, United States, using 600 volt DC streetcars and (in later years) buses.

The SDERy was established by sugar heir and land developer John D. Spreckels in ...

, founded by John D. Spreckels

John Diedrich Spreckels (August 16, 1853 – June 7, 1926), the son of German-American industrialist Claus Spreckels, founded a transportation and real estate empire in San Diego, California, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The entrepr ...

in 1892, was the major transit system in the San Diego area during that period. In the Los Angeles area, real estate tycoon Henry Huntington established both the Los Angeles Railway, also known as the Yellow Car system, and the above-mentioned Pacific Electric

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned Public transport, mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electr ...

Red Car System in 1901. The San Francisco Municipal Railway

The San Francisco Municipal Railway (SF Muni or Muni), is the public transit system for the City and County of San Francisco. It operates a system of bus routes (including trolleybuses), the Muni Metro light rail system, three historic cabl ...

was established in 1912. Business magnate Francis Marion Smith

Francis Marion Smith (February 2, 1846 – August 27, 1931) (once known nationally and internationally as "Borax Smith" and "The Borax King" ) was an American miner, business magnate and civic builder in the Mojave Desert, the San Francisc ...

then created the Key System

The Key System (or Key Route) was a privately owned company that provided mass transit in the cities of Oakland, California, Oakland, Berkeley, California, Berkeley, Alameda, California, Alameda, Emeryville, California, Emeryville, Piedmont, Ca ...

in 1903 to connect San Francisco with the East Bay. The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge

The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, known locally as the Bay Bridge, is a complex of bridges spanning San Francisco Bay in California. As part of Interstate 80 and the direct road between San Francisco and Oakland, it carries about 260,000 ...

opened to rail traffic in 1939 only to have the last trains run in 1958 after fewer than twenty years of service – the tracks were torn up and replaced with additional lanes for automobiles. All four streetcar systems, and other similar rail networks across the state, declined in the 1940s with the rise of California's car culture and freeway network. They were then all eventually taken over to some degree, and dismantled, in favor of bus service by National City Lines

National City Lines, Inc. (NCL) was a public transportation company. The company grew out of the Fitzgerald brothers' bus operations, founded in Minnesota, United States in 1920 as a modest local transport company operating two buses. Part of the ...

, a controversial national front company owned by General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

and other companies in what became known as the General Motors streetcar conspiracy. San Francisco's city-owned lines were not privatized, but were still largely converted to bus and trolleybuses

A trolleybus (also known as trolley bus, trolley coach, trackless trolley, trackless tramin the 1910s and 1920sJoyce, J.; King, J. S.; and Newman, A. G. (1986). ''British Trolleybus Systems'', pp. 9, 12. London: Ian Allan Publishing. .or trol ...

.

Modern light rail and subway systems

One urban system that survived the streetcar decline was the

One urban system that survived the streetcar decline was the San Francisco Municipal Railway

The San Francisco Municipal Railway (SF Muni or Muni), is the public transit system for the City and County of San Francisco. It operates a system of bus routes (including trolleybuses), the Muni Metro light rail system, three historic cabl ...

(Muni) in San Francisco. Its five heavily used streetcar lines traveled for at least part of their routes through tunnels or otherwise reserved right-of-way

Right of way is the legal right, established by grant from a landowner or long usage (i.e. by prescription), to pass along a specific route through property belonging to another.

A similar ''right of access'' also exists on land held by a gov ...

, and thus could not be converted to bus lines. As a result, these lines, running PCC streetcar

The PCC (Presidents' Conference Committee) is a streetcar (tram) design that was first built in the United States in the 1930s. The design proved successful in its native country, and after World War II it was licensed for use elsewhere in the ...

s, continued in operation for several decades. When plans for stations in the double-decker Market Street Subway tunnel through downtown San Francisco, with BART on the lower level and MUNI on the upper level, required high platforms, it meant that the PCCs could not be used in them. Hence, MUNI ordered a fleet of new light rail vehicles, and Muni Metro

Muni Metro is a light rail system serving San Francisco, California, United States. Operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), a part of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), Muni Metro served an average of 15 ...

began service in 1980. The San Francisco cable car system

The San Francisco cable car system is the world's last manually operated cable car system and an icon of the city of San Francisco. The system forms part of the intermodal urban transport network operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railwa ...

came under full Municipal ownership in 1952, and was declared a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

in 1964 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

in 1966 after almost being replaced entirely by buses in the previous decades. The system had fallen into disrepair by the 70s and a massive overhaul of the system resulted in the lines current configuration opening in 1984.

Planning for a modern, urban rapid transit

Rapid transit or mass rapid transit (MRT), also known as heavy rail or metro, is a type of high-capacity public transport generally found in urban areas. A rapid transit system that primarily or traditionally runs below the surface may be ...

system in California did not begin until the 1950s, when California's legislature created a commission to study the Bay Area's long-term transportation needs. Based on the commission's report, the state legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District in 1957 to build a rapid transit system to replace the Key System and provide region-wide rail connectivity. Initially intended to include all nine counties that ring the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

, the final system would feature service between San Francisco and three branches in the East Bay

The East Bay is the eastern region of the San Francisco Bay Area and includes cities along the eastern shores of the San Francisco Bay and San Pablo Bay. The region has grown to include inland communities in Alameda and Contra Costa counties ...

, serving three counties total. Passenger service on BART then began in 1972, but expansion to the system was planned almost immediately.

Environmental and traffic concerns beginning in the 1970s led to a resurgence in urban passenger rail, specifically the construction light rail networks.

Environmental and traffic concerns beginning in the 1970s led to a resurgence in urban passenger rail, specifically the construction light rail networks. Hurricane Kathleen

Hurricane Kathleen was a tropical cyclone that had a destructive impact in California. On September 7, 1976, a tropical depression formed; two days later it accelerated north towards the Baja California Peninsula. Kathleen brushed the Pacific ...

in 1976 damaged the San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway

The San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway Company is a short-line United States, American railroad founded in 1906 as the San Diego and Arizona Railway (SD&A) by sugar magnate, developer, and entrepreneur John D. Spreckels. Dubbed "The Impossi ...

Desert Line to San Diego, and the San Diego portion became an isolated railway. After prior decades of grappling with the option of building rapid transit BART-like line, light rail was eventually chosen as a more cost-effective solution. The San Diego Trolley

The San Diego Trolley is a light rail system operating in the metropolitan area of San Diego. It is known colloquially as "The Trolley". The Trolley's operator, San Diego Trolley, Inc. (SDTI), is a subsidiary of the San Diego Metropolitan Tra ...

opened in 1981 partially as a means to preserve freight service on this line, but is widely considered the system that lead to renewal in the concept of urban passenger rail. This system was followed in California by both the Sacramento Regional Transit Light Rail and Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority light rail

VTA Light Rail is a light rail system in San Jose and nearby cities in Santa Clara County, California. It is operated by the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, or VTA, and consists of of network comprising three main lines on sta ...

systems in 1987, as well as more nationwide.

The development of the mixed-mode Los Angeles Metro Rail began as two separate undertakings. The Southern California Rapid Transit District was planning a new subway along Wilshire Boulevard while the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission

The Southern California Rapid Transit District (almost always referred to as ''RTD'' or rarely as ''SCRTD'') was a public transportation agency established in 1964 to serve the Greater Los Angeles area. It was the successor to the original Los ...

was also designing a light rail system utilizing a former Pacific Electric

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned Public transport, mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electr ...

corridor. The light rail Blue Line opened to Long Beach in 1990. The Red rapid transit line began construction in 1986, and its first segment opened in 1993, the year both entities were merged. Expansion of the system was initially hampered by compromises and prohibiting legislation, but the light rail Green Line opened in 1995, followed by the Red Line's extension to in Koreatown

A Koreatown ( Korean: 코리아타운), also known as a Little Korea or Little Seoul, is a Korean-dominated ethnic enclave within a city or metropolitan area outside the Korean Peninsula.

History

Koreatowns as an East Asian ethnic enclave have ...

(which received its own designation as the Purple Line in 2006).

Passenger rail

Amtrak era

When

When Amtrak

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, doing business as Amtrak () , is the national passenger railroad company of the United States. It operates inter-city rail service in 46 of the 48 contiguous U.S. States and nine cities in Canada. ...

assumed operation of passenger rail services in the United States in 1971, most long-haul and commuter trains ceased operation. New lines were either based on previous routings or extended from old services. Service to Denver was provided via the ''San Francisco Zephyr

The ''San Francisco Zephyr'' was an Amtrak passenger train that ran between Chicago and Oakland from June 1972 to July 1983.

History

From the start of Amtrak in spring 1971 until summer 1972, Amtrak service between Chicago and Oakland was provi ...

'' (on a route largely retained from the ''City of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

''), and extended through to Chicago in 1983 with the ''California Zephyr

The ''California Zephyr'' is a passenger train operated by Amtrak between Chicago and the San Francisco Bay Area (at Emeryville), via Omaha, Denver, Salt Lake City, and Reno. At , it is Amtrak's longest daily route, and second-longest overall ...

''. Los Angeles services have remained largely unchanged since the corporation's inception. The ''Southwest Chief

The ''Southwest Chief'' (formerly the ''Southwest Limited'' and ''Super Chief'') is a passenger train operated by Amtrak on a route between Chicago and Los Angeles through the Midwest and Southwest via Kansas City, Albuquerque, and Flags ...

'' is the successor to the ATSF ''Super Chief

The ''Super Chief'' was one of the named passenger trains and the flagship of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The streamliner claimed to be "The Train of the Stars" because of the various celebrities it carried between Chicago, Ill ...

'', still running from Chicago. The ''Sunset Limited

The ''Sunset Limited'' is an Amtrak passenger train that for most of its history has operated between New Orleans and Los Angeles, over the nation's second transcontinental route. However, up until Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it operated betw ...

'' to New Orleans is the oldest maintained named train service in the United States, inherited from the Southern Pacific service running since 1894. The ''Texas Eagle

The ''Texas Eagle'' is a daily passenger train route operated by Amtrak between Chicago and San Antonio in the central and western United States. Prior to 1988, the train was known as the ''Eagle''.

Trains #21 (southbound) and 22 (northbound) ...

'' is a direct successor to the Missouri Pacific train of the same name. No one passenger train ran the length of the west coast before 1971. ''Coast Starlight

The ''Coast Starlight'' is a passenger train operated by Amtrak on the West Coast of the United States between Seattle and Los Angeles via Portland and the San Francisco Bay Area. The train, which has operated continuously since Amtrak's format ...

'' service was initiated as a thrice weekly service from Seattle to San Diego, later expanded to run daily but cut back to Los Angeles by 1972. Services to Las Vegas, Nevada

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vega ...

were provided by the weekend-only ''Las Vegas Limited

The ''Las Vegas Limited'' was a short-lived weekend-only passenger train operated by Amtrak between Los Angeles, California, and Las Vegas, Nevada. It was the last in series of excursion trains run by Amtrak between 1972–1976 serving the Los Ang ...

'' in 1976 and long-distance ''Desert Wind

The ''Desert Wind'' was an Amtrak long-distance passenger train that ran from 1979 to 1997. It operated from Chicago to Los Angeles as a section of the ''California Zephyr'', serving Los Angeles via Salt Lake City; Ogden, Utah; and Las Vegas.

...

'', which operated between 1979 and 1997.

Caltrans and Amtrak partnered together to form Amtrak California

Amtrak California is a brand name used by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) Division of Rail for three state-supported Amtrak commuter rail routes in Californiathe ''Capitol Corridor'', the ''Pacific Surfliner'', and the ...

in 1976. The ''Pacific Surfliner

The ''Pacific Surfliner'' is a passenger train service serving the communities on the coast of Southern California between San Diego and San Luis Obispo.

The service carried 2,924,117 passengers during fiscal year 2016, a 3.4% increase from F ...

'', serving the coastal communities of Southern California between San Diego and San Luis Obispo

San Luis Obispo (; Spanish for " St. Louis the Bishop", ; Chumash: ''tiłhini'') is a city and county seat of San Luis Obispo County, in the U.S. state of California. Located on the Central Coast of California, San Luis Obispo is roughly hal ...