cuius regio, eius religio on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

() is a

() is a

These specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades. Perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. By 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression:

These specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades. Perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. By 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression:

() is a

() is a Latin phrase

__NOTOC__

This is a list of Wikipedia articles of Latin phrases and their translation into English.

''To view all phrases on a single, lengthy document, see: List of Latin phrases (full)''

The list also is divided alphabetically into twenty page ...

which literally means "whose realm, their religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle

A legal doctrine is a framework, set of rules, procedural steps, or test, often established through precedent in the common law, through which judgments can be determined in a given legal case. A doctrine comes about when a judge makes a ruling ...

marked a major development in the collective (if not individual) freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

within Western civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

. Before tolerance of individual religious divergences became accepted, most statesmen and political theorists took it for granted that religious diversity

Interfaith dialogue refers to cooperative, constructive, and positive interaction between people of different religious traditions (i.e. "faiths") and/or spiritual or humanistic beliefs, at both the individual and institutional levels. It i ...

weakened a state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

– and particularly weakened ecclesiastically-transmitted control and monitoring in a state. The principle of was a compromise in the conflict between this paradigm of statecraft and the emerging trend toward religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and tolerating the religious diversity of a society or coun ...

(coexistence within a single territory) developing throughout the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. It permitted assortative migration of adherents to just two theocracies, Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, eliding other confessions.

At the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which ended a period of armed conflict between Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

forces within the Holy Roman Empire, the rulers of the German-speaking states and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

, agreed to accept this principle. In practice the principle had already been implemented between the time of the Nuremberg Religious Peace

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

of 1532 and the 1546–1547 Schmalkaldic War

The Schmalkaldic War (german: link=no, Schmalkaldischer Krieg) was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (simultaneously King Charles I of Spain), commanded by the Duk ...

. Now legal in the ''de jure'' sense, it was to apply to all the territories of the Empire except for the Ecclesiastical principalities and some of the cities in those ecclesiastical states, where the question of religion was addressed under the separate principles of the and the , which also formed part of the Peace of Augsburg. This agreement marked the end of the first wave of organized military action between Protestants and Catholics; however, these principles were factors during the wars of the 1545–1648 Counter-Reformation.

This left out other Reformed forms of Christianity (such as Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

) and radical systems such as Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

. However, some non-Lutherans passed for Lutherans with the assistance of the Augsburg Confession Variata The Altered Augsburg Confession (Lat. ''Confessio Augustana Variata'') is a later version of the Lutheran Augsburg Confession that includes substantial differences with regard to holy communion and the presence of Christ in bread and wine.

Philipp ...

. Practices other than the two which were the most widespread in the Empire was expressly forbidden, considered by the law to be heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, and could be punishable by death. Although "cuius regio" did not explicitly intend to allow the modern ideal of "freedom of conscience", individuals who could not subscribe to their ruler's religion were permitted to leave his territory with their possessions. Also under the , Lutheran knights were given the freedom to retain their religion wherever they lived. The revocation of the by the Catholics in the 1629 Edict of Restitution

The Edict of Restitution was proclaimed by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, on 6 March 1629, eleven years into the Thirty Years' War. Following Catholic military successes, Ferdinand hoped to restore control of land to that specifie ...

helped fuel the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

of 1618–1648. The Edict of Restitution itself was overturned in the 1635 Peace of Prague, which restored the 1555 terms of the Peace of Augsburg. Stability brought by assortative migrations under the principle were threatened by subsequent conversion of rulers. Therefore, the Peace of Westphalia preserved the essence of the principle by prohibiting converting rulers to force-convert their subjects and by determining the official religion of Imperial territories to the status of 1624 as a normative year.

Although some dissenters emigrated, others lived as Nicodemite

A Nicodemite () is a person suspected of publicly misrepresenting their religious faith to conceal their true beliefs. The term is sometimes defined as referring to a Protestant Christian who lived in a Roman Catholic country and escaped persecuti ...

s. Because of geographical and linguistic circumstances on the continent of Europe, emigration was more feasible for Catholics living in Protestant lands than for Protestants living in Catholic lands. As a result, there were more crypto-Protestants than crypto-Papists in continental Europe.

Religious divisions in the Empire

Prior to the 16th century and after the Great Schism, there had been one dominant faith in Western and Central European Christendom, and that was theRoman Catholic faith

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Heretical sects that arose during that period, such as the Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

and Waldenses

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" i ...

, were either quickly extinguished or made irrelevant. Chief figures during the later period, prominently being John Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspi ...

and Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

, at first called for the reform of the Catholic Church, but not necessarily a rejection of the faith ''per se''. Later on, Luther's movement broke away from the Catholic Church and formed the Lutheran denomination. Initially dismissed by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) ...

as an inconsequential argument between monks, the idea of a religious reformation accentuated controversies and problems in many of the territories of the Holy Roman Empire, which became engulfed in the ensuing controversy. The new Protestant theology galvanized social action in the German Peasants' War (1524–1526), which was brutally repressed and the popular political and religious movement crushed. In 1531, fearful of a repetition of similar suppression against themselves, several Lutheran princes formed the Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

, an alliance through which they agreed to protect themselves and each other from territorial encroachment, and which functioned as a political alliance against Catholic princes and armies.

It was broadly understood by princes and Catholic clergy alike that growing institutional abuse Institutional abuse is the maltreatment of a person (often children or older adults) from a system of power. This can range from acts similar to home-based child abuse, such as neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and hunger, to the effects of assist ...

s within the Catholic Church hindered the practices of the faithful. In 1537, Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

had called a council to examine the abuses and to suggest and implement reforms. In addition, he instituted several internal reforms. Despite these efforts, and the cooperation of Charles V, rapprochement of the Protestants with Catholicism foundered on different concepts of ecclesiology

In Christian theology, ecclesiology is the study of the Church (congregation), Church, the origins of Christianity, its relationship to Jesus, its role in salvation, its ecclesiastical polity, polity, its Church discipline, discipline, its escha ...

and the principle of justification. In the same year, the Schmalkaldic League called its own council, and posited several precepts of faith; Luther was present, but too ill to attend the meetings. When the delegates met again, this time in Regensburg in 1540–41, representatives could agree on the doctrine of faith and justification, but not on the number of sacraments, especially whether or not confession/absolution was sacramental, and they differed widely on the definition of "church". Catholic and Lutheran adherents seemed further apart than ever; in only a few towns and cities were Lutherans and Catholics able to live together in even a semblance of harmony. By 1548, political disagreements overlapped with religious issues, making any kind of agreement seem remote.

In 1548 Charles declared an ''interreligio imperialis'' (also known as the Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim (full formal title: ''Declaration of His Roman Imperial Majesty on the Observance of Religion Within the Holy Empire Until the Decision of the General Council'') was an imperial decree ordered on 15 May 1548 at the 1548 Diet ...

) through which he sought to find some common ground. This effort succeeded in alienating Protestant and Catholic princes and the ''Curia''; even Charles, whose decree it was, was unhappy with the political and diplomatic dimensions of what amounted to half of a religious settlement. The 1551–52 sessions convened by Pope Julius III

Pope Julius III ( la, Iulius PP. III; it, Giulio III; 10 September 1487 – 23 March 1555), born Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 February 1550 to his death in March 155 ...

at the Catholic Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described a ...

restated and reaffirmed Catholic teaching and condemned anew the Protestant heresies.Holborn, p. 241. The Council played an important part in the reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

of the Catholic Church in the 17th and 18th centuries.

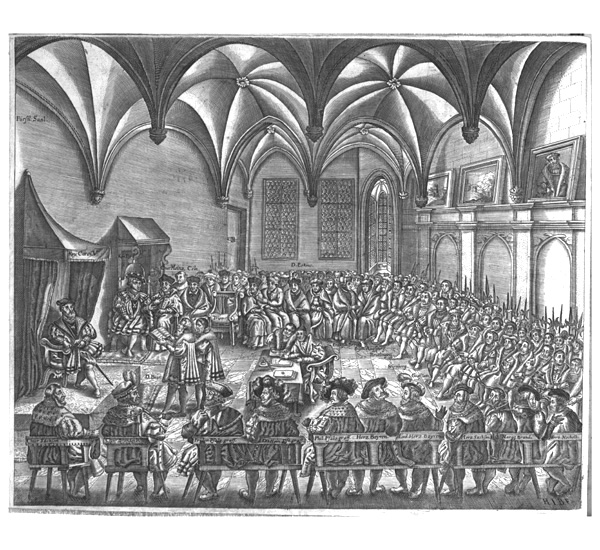

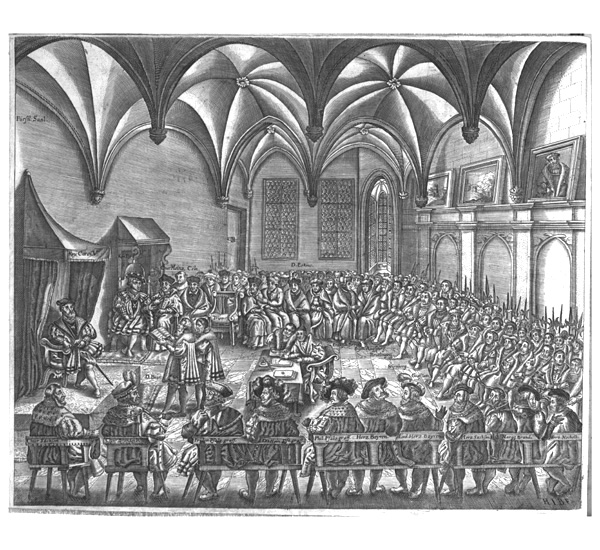

Augsburg Diet

Catholic and Protestant ideology seemed further apart than ever. Charles' interim solution satisfied no one. He ordered a general Diet in Augsburg at which the various states would discuss the religious problem and its solution (this should not be confused with theDiet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessi ...

in 1530). He himself did not attend, and delegated authority to his brother, Ferdinand, to "act and settle" disputes of territory, religion and local power. At the conference, Ferdinand cajoled, persuaded and threatened the various representatives into agreement on three important principles: ''cuius regio, eius religio'', ecclesiastical reservation, and the Declaration of Ferdinand.

''Cuius regio, eius religio''

The principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio'' provided for internal religious unity within a state: The religion of the prince became the religion of the state and all its inhabitants. Those inhabitants who could not conform to the prince's religion were allowed to leave, an innovative idea in the 16th century; this principle was discussed at length by the various delegates, who finally reached agreement on the specifics of its wording after examining the problem and the proposed solution from every possible angle. ''Cuius regio, eius religio'' went against earlier Catholic teaching, which held that the kings should faithfully obey the pope. This obedience was thought to produce greater fruits of cooperation and less political infighting and fewer church divisions. The phrase ''cuius regio, eius religio'' was coined in 1582 by thelegist

A Legist, from the Latin ''lex'' 'law', is any expert or student of law.

It was especially used since the Carolingian dynasty for royal councillors who advised the monarch in legal matters, and specifically helped base its absolutist ambitions on ...

Joachim Stephani

Joachim (; ''Yəhōyāqīm'', "he whom Tetragrammaton, Yahweh has set up"; ; ) was, according to Christian tradition, the husband of Saint Anne and the father of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The story of Joachim and Anne first appears in the Bibl ...

(1544–1623) of the University of Greifswald

The University of Greifswald (; german: Universität Greifswald), formerly also known as “Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University of Greifswald“, is a public research university located in Greifswald, Germany, in the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pom ...

.

Second and third principles of Augsburg Peace

The second principle covered the special status of the ecclesiastical states, called the ecclesiastical reservation, or ''reservatum ecclesiasticum''. If a prince-bishop orprince-abbot

A prince-abbot (german: Fürstabt) is a title for a cleric who is a Prince of the Church (like a Prince-bishop), in the sense of an ''ex officio'' temporal lord of a feudal entity, usually a State of the Holy Roman Empire. The territory ruled ...

changed his religion, he would have to relinquish his rule, allowing the chapter to elect a Catholic successor.

The third principle, known as '' Ferdinand's declaration'', exempted knights and some of the cities in ecclesiastical states from the requirement of religious uniformity, if the reformed religion had been practiced there since the mid-1520s, allowing for a few mixed cities and towns where Catholics and Lutherans had lived together. Ferdinand inserted this at the last minute, on his own authority.

Legal ramifications

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the coexistence of Catholic and Lutheran faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the so-called Old Faith and the followers of Luther. It had two fundamental flaws. First, Ferdinand had rushed the article on ''ecclesiastical reservation'' through the debate; it had not undergone the scrutiny and discussion that attended the acceptance of ''Cuius regio, eius religio''. Consequently, its wording did not cover all, or even most, potential legal scenarios. His ''ad hoc'' ''Declaratio Ferdinandei'' was not debated in plenary session at all; instead, using his authority to "act and settle", he had added it at the last minute, responding to lobbying by princely families and knights. These specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades. Perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. By 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression:

These specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades. Perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. By 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression: Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

, such as the Frisian Menno Simons

Menno Simons (1496 – 31 January 1561) was a Roman Catholic priest from the Friesland region of the Low Countries who was excommunicated from the Catholic Church and became an influential Anabaptist religious leader. Simons was a contemporary ...

(1492–1559) and his followers; the followers of John Calvin, who were particularly strong in the southwest and the northwest; or those of Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

, were excluded from considerations and protections under the Peace of Augsburg. According to the Religious Peace, their religious beliefs were officially heretical, and would remain so in lands under the direct rule of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

until the Patent of Toleration

The Patent of Toleration (german: Toleranzpatent) was an edict of toleration issued on 13 October 1781 by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II. Part of the Josephinist reforms, the Patent extended religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians livi ...

in 1781.

Application in secular territories

The idea of individualreligious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

on a national level was, however, not addressed: neither the Reformed nor Radical churches ( Calvinists and Anabaptists being the prime examples) were protected under the peace (and Anabaptists would reject the principle of ''cuius regio eius religio'' in any case). Crypto-Calvinists

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Lut ...

were accommodated by Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, who supplied them with altered versions of the Augsburg Confession adapted to Reformed beliefs. One historical example is the case of Hessen-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, was a state in the Holy Roman Empire that was imperial immediacy, directly subject to the Emperor. The state was created i ...

, where even though the Augsburg Confession was adopted in 1566, the territory was ''de facto'' Reformed even then, and continued as such until officially adopting a Reformed confession of faith in 1605.

Many Protestant groups living under the rule of Catholic or Lutheran noble still found themselves in danger of the charge of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. Tolerance was not officially extended to Calvinists until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, and most Anabaptists eventually relocated east to Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, the Warsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation, signed on 28 January 1573 by the Polish national assembly (''sejm konwokacyjny'') in Warsaw, was one of the first European acts granting religious freedoms. It was an important development in the history of Poland and o ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, or Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, west to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

, or were martyred

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

.

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 limited all rulers in the Holy Roman Empire except the Emperor to change their religion but not impose it on their subjects anymore, rulers choosing to convert had to tolerate the religions that were already in place. For example, Frederick Augustus I, Elector of Saxony

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I – Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as Ki ...

converted to Catholicism in 1697 in order to become King of Poland, but the Electorate of Saxony had to remain officially Protestant. The Elector of Saxony even managed to retain the directorship of the Protestant body in the Reichstag.

John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg

John Sigismund (german: Johann Sigismund; 8 November 1572 – 23 December 1619) was a Prince-elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg from the House of Hohenzollern. He became the Duke of Prussia through his marriage to Duchess Anna, the eld ...

converted to Calvinism in 1613, but his subjects remained predominantly Lutheran. Brandenburg-Prussia remained a bi-confessional state in which both Lutheranism and Calvinism were official religions until the 1817 Prussian Union of Churches. The Electors of Brandenburg already tolerated Catholicism in Ducal Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establishe ...

, which lay outside the borders of the Holy Roman Empire and was held in fief to the King of Poland. They would later acquire other Catholic territories in Poland, but imposed taxes of up to 80% on church revenues. Brandenburg-Prussia also acquired territories in western Germany where Catholicism was the official religion. In 1747, Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

gave permission for a Catholic cathedral, St. Hedwig's Cathedral, to be built in the predominantly Lutheran capital city of Berlin.End of Cuius regio, eius religio

Application in ecclesiastical territories

No agreement had been reached on the question of whether Catholicbishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

s and abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fem ...

s who became Lutheran should lose their offices and incomes until Peace of Augsburg under the reservatum ecclesiasticum

The ' (Latin, "ecclesiastical reservation"; ) was a provision of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555. It exempted ecclesiastical lands from the principle of ' (Latin: whose land, his religion), which the Peace established for all hereditary dynas ...

clause. However prior to this in 1525, Albert, Duke of Prussia

Albert of Prussia (german: Albrecht von Preussen; 17 May 149020 March 1568) was a German prince who was the 37th Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, who after converting to Lutheranism, became the first ruler of the Duchy of Prussia, the s ...

had converted to Lutheranism and expelled the Teutonic Knights. He was able to officially change his lands to the Lutheran faith and convert his ecclesiastical position as Grand Master of the Order into a secular duchy. When Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg

Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg (10 November 1547 – 31 May 1601) was Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. After pursuing an ecclesiastical career, he won a close election in the cathedral chapter of Cologne over Ernst of Bavaria. After his ...

converted to the Reformed faith, he thought he could do the same, despite the terms of the ''Peace of Augsburg''. Catholics appointed Ernest of Bavaria

Ernest of Bavaria (german: Ernst von Bayern) (17 December 1554 – 17 February 1612) was Prince-elector-archbishop of the Archbishopric of Cologne from 1583 to 1612 as successor of the expelled Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg. He was also bishop ...

to be the new Archbishop-Elector and fought the five-year war Cologne War. Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg was exiled and Cologne remained Roman Catholic.Parker, Geoffrey. ''The Thirty Years' War.'' p. 17.

The Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück

The Prince-Bishopric of OsnabrückAlso known as the Prince-Bishopric of Osnaburg) (german: link=no, Hochstift Osnabrück; Fürstbistum Osnabrück, Bistum Osnabrück) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1225 until 1803. ...

was an exception to ''cuius regio, eius religio''. Osnabrück gradually became more Lutheran after 1543, with the conversion or election of several Protestant bishops. However, it never became fully Lutheran, as Catholic services were still held and Catholic bishops were also elected. In the Peace of Westphalia, which was partially negotiated in Osnabrück, both the Catholic and Lutheran religions were restored to the status they held in Osnabrück in 1624. Osnabrück remained an ecclesiastical territory ruled by a prince-bishop, but the office would be held alternately by a Catholic bishop and a Lutheran bishop, who was selected from what became the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house or ...

. While the territory was ruled by a Lutheran bishop, the Catholics would be under the supervision of the Archbishop of Cologne.

In 1731, Prince-Archbishop von Firmian of Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

decided to recatholicize his territory. At first this included the seizing of Protestant children from their parents so they could be raised in a Catholic institution. The Prince-Archbishop requested Imperial and Bavarian troops to aid in the suppression of approximately 20,000 Lutherans living in Salzburg. When the Archbishop claimed they were radicals, they were examined and determined to be Lutherans of the ordinary sort. He expelled them anyway, which was technically legal under the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

In February 1732, King Frederick William I of Prussia

Frederick William I (german: Friedrich Wilhelm I.; 14 August 1688 – 31 May 1740), known as the "Soldier King" (german: Soldatenkönig), was King in Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg from 1713 until his death in 1740, as well as Prince of Neuch ...

offered to resettle them in eastern Prussia. Others found their way to Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

or the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

. Additionally, a community of Salzburgers settled in the British colony of Georgia

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

.

In 1966, Archbishop expressed regret about the expulsions.

See also

* ''Res publica Christiana

In medieval and early modern Western political thought, the ''respublica'' or ''res publica Christiana'' refers to the international community of Christian peoples and states. As a Latin phrase, ''res publica Christiana'' combines Christianity wi ...

'', the medieval and Renaissance concept of a united Christendom

Notes

References

* Holborn, Hajo, ''A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959982

Year 982 ( CMLXXXII) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* Summer – Emperor Otto II (the Red) assembles an imperial expeditionary force at Tar ...

*Jedin, Hubert, ''Konciliengeschichte'', Freiburg, Herder, 1980, .

* Ozment, Steven, ''The Age of Reform 1250–1550, An Intellectual and Religious History of Late Medieval and Reformation Europe'', New Haven, Yale University Press, 1986,

*

Further reading

*Brady, Thomas, et al. (1995). ''Handbook of European History, 1400–1600'', v. 2. Leiden: Brill. *Brodek, Theodor V (1971). "Socio-Political Realities of the Holy Roman Empire". ''Journal of Interdisciplinary History '' 1 (3): 395–405. 1971. *Sutherland, N.M. . "Origins of the Thirty Years War and the Structure of European Politics". ''The English Historical Review'' 107 (424): 587–625. 1992. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cuius Regio, Eius Religio Latin legal terminology Christianity in the Holy Roman Empire Religion and politics ru:Cuius regio, eius religio