Cristero rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cristero War ( es, Guerra Cristera), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or es, La Cristiada, label=none, italics=no , was a widespread struggle in central and western

''Religious Culture in Modern Mexico''

pp. 228–29, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007 Calles applied the anticlerical laws stringently throughout the country and added his own anticlerical legislation. In June 1926, he signed the "Law for Reforming the Penal Code," which was unofficially called

In response to the measures, Catholic organizations began to intensify their resistance. The most important group was the

In response to the measures, Catholic organizations began to intensify their resistance. The most important group was the

On August 14, government agents staged a purge of the

On August 14, government agents staged a purge of the

The Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico's Cristero Rebellion

p. 55, University of Arizona Press, 1982 That sentiment was held also by Calles. However, the rebels planned their battles fairly well considering that most of them had little to no previous military experience. The most successful rebel leaders were Jesús Degollado, a pharmacist;

However, the rebels planned their battles fairly well considering that most of them had little to no previous military experience. The most successful rebel leaders were Jesús Degollado, a pharmacist;

The Anti-clerical Who Led a Catholic Rebellion

Latin American Studies At least five priests took up arms, and many others supported them in various ways. Many of the rebel peasants who took up arms in the fight had different motivations from the Catholic Church. Many were still fighting for agrarian On February 23, 1927, the Cristeros defeated federal troops for the first time at

On February 23, 1927, the Cristeros defeated federal troops for the first time at

In October 1927, the American ambassador,

In October 1927, the American ambassador,  In September 1928, Congress named

In September 1928, Congress named  Morrow managed to bring the parties to agreement on June 21, 1929. His office drafted a pact called the ''arreglos'' ("agreement"), which allowed worship to resume in Mexico and granted three concessions to the Catholics. Only priests who were named by hierarchical superiors would be required to register; religious instruction in churches but not in schools would be permitted; and all citizens, including the clergy, would be allowed to make petitions to reform the laws. However, the most important parts of the agreement were that the Church would recover the right to use its properties, and priests would recover their rights to live on the properties. Legally speaking, the Church was not allowed to own real estate, and its former facilities remained federal property. However, the Church effectively took control over the properties. In the convenient arrangement for both parties, the Church ostensibly ended its support for the rebels.

Morrow managed to bring the parties to agreement on June 21, 1929. His office drafted a pact called the ''arreglos'' ("agreement"), which allowed worship to resume in Mexico and granted three concessions to the Catholics. Only priests who were named by hierarchical superiors would be required to register; religious instruction in churches but not in schools would be permitted; and all citizens, including the clergy, would be allowed to make petitions to reform the laws. However, the most important parts of the agreement were that the Church would recover the right to use its properties, and priests would recover their rights to live on the properties. Legally speaking, the Church was not allowed to own real estate, and its former facilities remained federal property. However, the Church effectively took control over the properties. In the convenient arrangement for both parties, the Church ostensibly ended its support for the rebels.

Over the previous two years, anticlerical officers, who were hostile to the federal government for reasons other than its position on religion, had joined the rebels. When the agreement between the government and the Church was made known, only a minority of the rebels went home, mainly those who felt their battle had been won. On the other hand, since the rebels themselves had not been consulted in the talks, many felt betrayed, and some continued to fight. The Church threatened those rebels with excommunication and the rebellion gradually died out. The officers, fearing that they would be tried as traitors, tried to keep the rebellion alive. Their attempt failed, and many were captured and shot, and others escaped to

Over the previous two years, anticlerical officers, who were hostile to the federal government for reasons other than its position on religion, had joined the rebels. When the agreement between the government and the Church was made known, only a minority of the rebels went home, mainly those who felt their battle had been won. On the other hand, since the rebels themselves had not been consulted in the talks, many felt betrayed, and some continued to fight. The Church threatened those rebels with excommunication and the rebellion gradually died out. The officers, fearing that they would be tried as traitors, tried to keep the rebellion alive. Their attempt failed, and many were captured and shot, and others escaped to

Catholic World Report, June 1, 2012 They circulated five million leaflets about the war in the United States, held hundreds of lectures, spread the news via radio, and paid to "smuggle" a friendly journalist into Mexico so he could cover the war for an American audience. In addition to lobbying the American public, the Knights met United States President

The government often did not abide by the terms of the truce. For example, it executed some 500 Cristero leaders and 5,000 other Cristeros.Van Hove, Bria

The government often did not abide by the terms of the truce. For example, it executed some 500 Cristero leaders and 5,000 other Cristeros.Van Hove, Bria

Blood-Drenched Altars

Faith & Reason 1994 Catholics continued to oppose Calles's insistence on a state monopoly on education, which suppressed Catholic education and introduced secular education in its place: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth." Calles's military persecution of Cristeros after the truce would be officially condemned by Mexican President

The Catholic Church has recognized several of those who were killed in the Cristero War as

The Catholic Church has recognized several of those who were killed in the Cristero War as

"Cristero Martyrs, Jalisco Nun To Attain Sainthood"

. ''Guadalajara Reporter''. May 12, 2000 They had been beatified on November 22, 1992. Of this group, 22 were

; ''Catholic News Agency''; November 5, 2005 This group was mostly lay people, including Luis Magaña Servín and 14-year-old

in JSTOR

* Espinosa, David. "'Restoring Christian Social Order': The Mexican Catholic Youth Association (1913–1932)", ''The Americas'' (2003) 59#4 pp. 451–47

in JSTOR

* Jrade, Ramon. "Inquiries into the Cristero Insurrection against the Mexican Revolution", ''Latin American Research Review'' (1985) 20#2 pp. 53–6

in JSTOR

* Meyer, Jean. ''The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People between Church and State, 1926–1929''. Cambridge, 1976. * Miller, Sr. Barbara. "The Role of Women in the Mexican Cristero Rebellion: Las Señoras y Las Religiosas", ''The Americas'' (1984) 40#3 pp. 303–32

in JSTOR

* Lawrence, Mark. 2020. Insurgency, Counter-insurgency and Policing in Centre-West Mexico, 1926–1929. Bloomsbury. * Purnell, Jenny. ''Popular Movements and State Formation in Revolutionary Mexico: The Agraristas and Cristeros of Michoacán''. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999. * Quirk, Robert E. ''The Mexican Revolution and the Catholic Church, 1910–1929'', Greenwood Press, 1986. * Tuck, Jim. ''The Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico's Cristero Rebellion''. University of Arizona Press, 1982. * Young, Julia. ''Mexican Exodus: Emigrants, Exiles, and Refugees of the Cristero War''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

online

Cristeros (Soldiers of Christ) – Documentary

* Ferreira, Cornelia R

biography (2006 Canisius Books).

– encyclical of Pope Pius XI on the persecution of the Church in Mexico (November 18, 1926)

Miss Mexico wears dress depicting Cristeros at the 2007 Miss Universe Pageant

– ''article by Gary Potter''. {{Authority control Cristero War, 1920s in Mexico 1920s conflicts Anti-clericalism in Mexico Rebellions in Mexico Religion-based civil wars Religiously motivated violence in Mexico Religious persecution Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America Civil wars of the Industrial era History of Catholicism in North America Persecution of Catholics Modern Mexico History of Aguascalientes History of Guanajuato History of Jalisco History of Michoacán History of Zacatecas 20th-century Catholicism Wars involving Mexico Catholic rebellions

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

from 1 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularist

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a sim ...

and anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

articles of the 1917 Constitution

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in th ...

. The rebellion was instigated as a response to an executive decree by Mexican President

The president of Mexico ( es, link=no, Presidente de México), officially the president of the United Mexican States ( es, link=no, Presidente de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the head of state and head of government of Mexico. Under the Co ...

Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

to strictly enforce Article 130 of the Constitution, a decision known as Calles Law

The Calles Law (), or Law for Reforming the Penal Code (''ley de tolerancia de cultos'', "law of worship tolerance"), was a statute enacted in Mexico in 1926, under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles, to enforce restrictions against the Ca ...

. Calles sought to eliminate the power of the Catholic Church in Mexico

, native_name_lang =

, image = Catedral_de_México.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt =

, caption = The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral.

, abbreviation =

, type = ...

, its affiliated organizations and to suppress popular religiosity.

The rural uprising in north-central Mexico was tacitly supported by the Church hierarchy, and was aided by urban Catholic supporters. The Mexican Army received support from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. American Ambassador Dwight Morrow

Dwight Whitney Morrow (January 11, 1873October 5, 1931) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician, best known as the U.S. ambassador who improved U.S.-Mexican relations, mediating the religious conflict in Mexico known as the Cristero ...

brokered negotiations between the Calles government and the Church. The government made some concessions, the Church withdrew its support for the Cristero fighters, and the conflict ended in 1929. The rebellion has been variously interpreted as a major event in the struggle between church and state that dates back to the 19th century with the War of Reform

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a civil war in Mexico lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservativ ...

, as the last major peasant uprising in Mexico after the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

in 1920, and as a counter-revolutionary uprising by prosperous peasants and urban elites against the revolution's rural and agrarian reforms.

Background

Conflict between church and state

TheMexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

was the costliest conflict in Mexican history

The written history of Mexico spans more than three millennia. First populated more than 13,000 years ago, central and southern Mexico (termed Mesoamerica) saw the rise and fall of complex indigenous civilizations. Mexico would later develop i ...

. The overthrow of the dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

caused political instability, with many contending factions and regions. The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the Díaz government had come to an informal ''modus vivendi'' in which the state formally maintained the anticlerical articles of the liberal Constitution of 1857

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Cong ...

but it failed to enforce them. A change of leadership or a wholesale overturning of the previous order were potential sources of danger to the Church's position. In the democratizing wave of political activity, the National Catholic Party (''Partido Católico Nacional'') was formed.

After president Francisco I. Madero

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who became the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'etat in February 1 ...

was overthrown and assassinated in a February 1913 military coup which was led by General Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero wit ...

, supporters of the Porfirian regime were returned to their posts. After the ouster of Huerta in 1914, members of the National Catholic Party and high-ranking Church figures were accused of collaborating with the Huerta regime, and the Catholic Church was subjected to revolutionary hostilities and fierce anticlericalism by many northern revolutionaries. The Constitutionalist

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

faction won the revolution and its leader, Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a February ...

, had a new constitution drawn up, the Constitution of 1917

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in th ...

. It strengthened the anticlerical provisions of the previous document, but President Carranza and his successor, General Alvaro Obregón, were preoccupied by their struggles with their internal enemies and as a result, they were lenient in their enforcement of the Constitution's anticlerical articles, especially in areas where the Church was powerful.

The administration of Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

believed that the Church was challenging its revolutionary initiatives and legal basis. To confront the Church's influence, anticlerical laws were instituted, which triggered a ten-year-long religious conflict in which thousands of armed civilians were killed by the Mexican Army. Some have characterized Calles as the leader of an atheist state

State atheism is the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. It is a form of religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically li ...

and his program as being one to eradicate religion in Mexico.

1917 Mexican Constitution

The1917 Constitution

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in th ...

was drafted by the Constituent Congress

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

convoked by Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a February ...

in September 1916, and it was approved on February 5, 1917. The new constitution was based in the 1857 Constitution

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Cong ...

, which had been instituted by Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Liberalism in Mexico, Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec peoples, Zapo ...

. Articles 3, 27, and 130 of the 1917 Constitution contained secularizing sections that restricted the power and the influence of the Catholic Church.

The first two sections of Article 3 stated: "I. According to the religious liberties established under article 24, educational services shall be secular and, therefore, free of any religious orientation. II. The educational services shall be based on scientific progress and shall fight against ignorance, ignorance's effects, servitudes, fanaticism and prejudice." The second section of Article 27 stated: "All religious associations organized according to article 130 and its derived legislation, shall be authorized to acquire, possess or manage just the necessary assets to achieve their objectives."

The first paragraph of Article 130 stated: "The rules established at this article are guided by the historical principle according to which the State and the churches are separated entities from each other. Churches and religious congregations shall be organized under the law."

The Constitution also provided for obligatory state registration of all churches and religious congregations and placed a series of restrictions on priests and ministers of all religions, who were not allowed to hold public office, canvas on behalf of political parties or candidates, or inherit from persons other than close blood relatives. It also allowed the state to regulate the number of priests in each region and even to reduce the number to zero, it forbade the wearing of religious garb outside of church or religious premises, and excluded offenders from a trial by jury. Carranza declared himself opposed to the final draft of Articles 3, 5, 24, 27, 123 and 130, but the Constitutional Congress contained only 85 conservatives and centrists who were close to Carranza's brand of liberalism. Against them were 132 delegates who were more radical.

Article 24 stated: "Every man shall be free to choose and profess any religious belief as long as it is lawful and it cannot be punished under criminal law. The Congress shall not be authorized to enact laws either establishing or prohibiting a particular religion. Religious ceremonies of public nature shall be ordinarily performed at the temples. Those performed outdoors shall be regulated under the law."

Crisis

Government forces publicly hanged Cristeros on main thoroughfares throughout Mexico, including in the Pacific states of Colima_and_Jalisco,_where_bodies_often_remained_hanging_for_extended_lengths_of_time..html" ;"title="Jalisco.html" ;"title="Colima and Jalisco">Colima and Jalisco, where bodies often remained hanging for extended lengths of time.">Jalisco.html" ;"title="Colima and Jalisco">Colima and Jalisco, where bodies often remained hanging for extended lengths of time. After a period of peaceful resistance to the enforcement of the anticlerical provisions of the Constitution by Mexican Catholics, skirmishing broke out in 1926, and violent uprisings began in 1927. The government called the rebels ''Cristeros'' since they invoked the name of Jesus Christ under the title of "Cristo Rey" or ''Christ the King'', and the rebels soon used the name themselves. The rebellion is known for the Feminine Brigades of St. Joan of Arc, a brigade of women who assisted the rebels in smuggling guns and ammunition, and for certain priests who were tortured and murdered in public and latercanonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christianity, Christian communion declaring a person worthy of Cult (religious practice), public veneration and enterin ...

by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

. The rebellion eventually ended by diplomatic means brokered by the American Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow, with financial relief and logistical assistance provided by the Knights of Columbus

The Knights of Columbus (K of C) is a global Catholic fraternal service order founded by Michael J. McGivney on March 29, 1882. Membership is limited to practicing Catholic men. It is led by Patrick E. Kelly, the order's 14th Supreme Knight. ...

.

The rebellion attracted the attention of Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

, who issued a series of papal encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally from ...

s from 1925 to 1937. On November 18, 1926, he issued ''Iniquis afflictisque

{{Modern persecutions of the Catholic Church

''Iniquis afflictisque'' (''On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico'') is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI promulgated on November 18, 1926, to denounce the persecution of the Catholic Church in Mexic ...

'' ("On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico") to denounce the violent anticlerical persecution in Mexico. Despite the government's promises, the persecution of the Church continued. In response, Pius issued ''Acerba animi

''Acerba animi'' (Latin, "Of harsh souls"; also called ''On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico'') is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI promulgated on 29 September 1932, to denounce the continued persecution of the Catholic Church in Mexico. ...

'' on September 29, 1932.

Background

Violence on a limited scale occurred throughout the early 1920s, but it never rose to the level of widespread conflict. In 1926, the passage of stringentanticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

criminal laws and their enforcement by the Calles Law

The Calles Law (), or Law for Reforming the Penal Code (''ley de tolerancia de cultos'', "law of worship tolerance"), was a statute enacted in Mexico in 1926, under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles, to enforce restrictions against the Ca ...

, together with peasant revolts in the heavily-Catholic Bajío

El Bajío (the ''lowland'') is a cultural and geographical region within the central Mexican plateau which roughly spans from north-west of the Mexico City metropolitan area to the main silver mines in the northern-central part of the country. Thi ...

and the clampdown on popular religious celebrations such as fiestas, caused scattered guerrilla operations to coalesce into a serious armed revolt against the government.

Both Catholic and anticlerical groups turned to terrorism. Of the several uprisings against the Mexican government in the 1920s, the Cristero War was the most devastating and had the most long-term effects. The diplomatic settlement of 1929 brokered by the American Ambassador Dwight Morrow

Dwight Whitney Morrow (January 11, 1873October 5, 1931) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician, best known as the U.S. ambassador who improved U.S.-Mexican relations, mediating the religious conflict in Mexico known as the Cristero ...

between the Catholic Church and the Mexican government was supported by the Vatican. Although many Cristeros continued fighting, the Church no longer gave them tacit support. The persecution of Catholics and anti-government terrorist attacks continued into the 1940s, when the remaining organized Cristero groups were incorporated into the Sinarquista Party.

The Mexican Revolution started in 1910 against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

and for the masses' demand of land for the peasantry. Francisco I. Madero

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who became the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'etat in February 1 ...

was the first revolutionary leader. He was elected president in November 1911 but was overthrown and executed in 1913 by conservative General Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero wit ...

in a series of events now known as the Ten Tragic Days

The Ten Tragic Days ( es, La Decena Trágica) during the Mexican Revolution is the name now given to a multi-day coup d'etat in Mexico City by opponents of Francisco I. Madero, the democratically elected president of Mexico, between 9 - 19 Feb ...

. After Huerta seized power, Archbishop Leopoldo Ruiz y Flóres

Leopoldo Ruiz y Flóres (13 November 1865 – 12 December 1941) was a Mexican prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Morelia from 1911 until his death in 1941. He was previously Bishop of Léon from 1900 to 1907 and Archbishop ...

from Morelia

Morelia (; from 1545 to 1828 known as Valladolid) is a city and municipal seat of the municipality of Morelia in the north-central part of the state of Michoacán in central Mexico. The city is in the Guayangareo Valley and is the capital and larg ...

published a letter condemning the coup and distancing the Church from Huerta. The newspaper of the National Catholic Party, representing the views of the bishops, severely attacked Huerta and so the new regime jailed the party's president and halted the publication of the newspaper. Nevertheless, some members of the party participated in Huerta's regime, such as Eduardo Tamariz. The revolutionary generals Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a February ...

, Francisco Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

and Emiliano Zapata

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (; August 8, 1879 – April 10, 1919) was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the ins ...

, who won against Huerta's federal army under the Plan of Guadalupe

The Plan of Guadalupe ( es, Plan de Guadalupe) was a political manifesto which was proclaimed on March 26, 1913, by the Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza in response to the reactionary coup d'etat and execution of President Francisco I. ...

, had friends among Catholics and the local parish priests who aided them but also blamed high-ranking Catholic clergy for supporting Huerta.

Carranza was the first president under the 1917 Constitution but he was overthrown by his former ally Álvaro Obregón

Álvaro Obregón Salido (; 17 February 1880 – 17 July 1928) better known as Álvaro Obregón was a Sonoran-born general in the Mexican Revolution. A pragmatic centrist, natural soldier, and able politician, he became the 46th President of Me ...

in 1919. Obregón took over the presidency in late 1920 and effectively applied the Constitution's anticlerical laws in areas in which the Church was fragile. The uneasy truce with the Church ended with Obregón's 1924 handpicked succession of the atheist Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

. Mexican Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

, supported by Calles's central government, engaged in secular antireligious campaigns to eradicate what they called "superstition" and "fanaticism," which included the desecration of religious objects as well as the persecution and the murder of members of the clergy.Martin Austin Nesvig''Religious Culture in Modern Mexico''

pp. 228–29, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007 Calles applied the anticlerical laws stringently throughout the country and added his own anticlerical legislation. In June 1926, he signed the "Law for Reforming the Penal Code," which was unofficially called

Calles Law

The Calles Law (), or Law for Reforming the Penal Code (''ley de tolerancia de cultos'', "law of worship tolerance"), was a statute enacted in Mexico in 1926, under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles, to enforce restrictions against the Ca ...

. It provided specific penalties for priests and individuals who violated the provisions of the 1917 Constitution. For instance, wearing clerical garb in public, outside church buildings, earned a fine of 500 pesos (then the equivalent of US$250), and priests who criticized the government could be imprisoned for five years. Some states enacted oppressive measures. Chihuahua enacted a law permitting only one priest to serve all Catholics in the state. To help enforce the law, Calles seized church property, expelled all foreign priests and closed monasteries, convents and religious schools.

Rebellion

Peaceful resistance

In response to the measures, Catholic organizations began to intensify their resistance. The most important group was the

In response to the measures, Catholic organizations began to intensify their resistance. The most important group was the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty

National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty ( es, Liga Nacional Defensora de la Libertad Religiosa – LNDLR) was a Mexican Catholic religious civil rights organization formed in March 1925 that played a crucial role in the Cristero War ...

, founded in 1924, which was joined by the Mexican Association of Catholic Youth, founded in 1913, and the Popular Union, a Catholic political party founded in 1925.

In 1926, Calles intensified tensions against the clergy by ordering all local churches in and around Jalisco to be bolted shut. The places of worship remained shut for two years. On July 14, Catholic bishops endorsed plans for an economic boycott against the government, which was particularly effective in west-central Mexico (the states of Jalisco

Jalisco (, , ; Nahuatl: Xalixco), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco ; Nahuatl: Tlahtohcayotl Xalixco), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal En ...

, Michoacán

Michoacán, formally Michoacán de Ocampo (; Purépecha: ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Michoacán de Ocampo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of ...

, Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, Aguascalientes

Aguascalientes (; ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Aguascalientes ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Aguascalientes), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. At 22°N and ...

, and Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

). Catholics in those areas stopped attending movies and plays and using public transportation, and Catholic teachers stopped teaching in secular schools.

The bishops worked to have the offending articles of the Constitution amended. Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

explicitly approved the plan. The Calles government considered the bishops' activism to be sedition and had many more churches closed. In September 1926, the episcopate submitted a proposal to amend the Constitution, but the Mexican Congress

The Congress of the Union ( es, Congreso de la Unión, ), formally known as the General Congress of the United Mexican States (''Congreso General de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos''), is the legislature of the federal government of Mexico cons ...

rejected it on September 22.

Escalation of violence

On August 3, inGuadalajara, Jalisco

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Mexico, while the Guadalaj ...

, some 400 armed Catholics shut themselves in the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe ("Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe"). They exchanged gunfire with federal troops and surrendered when they ran out of ammunition. According to American consular sources, the battle resulted in 18 dead and 40 wounded. The following day, in Sahuayo

Sahuayo ( Nahuatl: ''Tzacuātlayotl'') is a city in the state of Michoacán, in western México, near the southern shore of Lake Chapala. It serves as the municipal seat for the surrounding municipality of the same name. Sahuayo is an important c ...

, Michoacán

Michoacán, formally Michoacán de Ocampo (; Purépecha: ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Michoacán de Ocampo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of ...

, 240 government soldiers stormed the parish church. The priest and his vicar were killed in the ensuing violence.

On August 14, government agents staged a purge of the

On August 14, government agents staged a purge of the Chalchihuites

Chalchihuites is a municipality in the Mexican state of Zacatecas in northwest Mexico. The archaeological site of Altavista, at Chalchihuites, is located 137 miles to the northwest of the city of Zacatecas and 102 miles southeast of the city of Dur ...

, Zacatecas, chapter of the Association of Catholic Youth and executed its spiritual adviser, Father Luis Bátiz Sainz. The execution caused a band of ranchers, led by Pedro Quintanar, to seize the local treasury and to declare themselves in rebellion. At the height of the rebellion, they held a region including the entire northern part of Jalisco. Luis Navarro Origel, mayor of Pénjamo

Pénjamo ( tsz, Penlamu or Penxamo 'place of ahuehuetes or sabinos'; Cradle of Hidalgo) is the seat of Pénjamo municipality, one of 46 municipalities of Guanajuato, Mexico. It was cofounded in 1549 by Guamares, Purépechas, and Otomis prior to ...

, Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, led another uprising on September 28. His men were defeated by federal troops in the open land around the town but retreated into the mountains, where they engaged in guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

. In support of the two guerrilla Apache clans, the Chavez and Trujillos helped smuggle arms, munitions and supplies from the U.S. state of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

.

That was followed by a September 29 uprising in Durango

Durango (), officially named Estado Libre y Soberano de Durango ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Durango; Tepehuán: ''Korian''; Nahuatl: ''Tepēhuahcān''), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in ...

, led by Trinidad Mora, and an October 4 rebellion in southern Guanajuato, led by former General Rodolfo Gallegos. Both rebel leaders adopted guerrilla tactics since their forces were no match for federal troops. Meanwhile, rebels in Jalisco, particularly the region northeast of Guadalajara, quietly began assembling forces. Led by 27-year-old René Capistrán Garza, the leader of the Mexican Association of Catholic Youth, the region would become the main focal point of the rebellion.

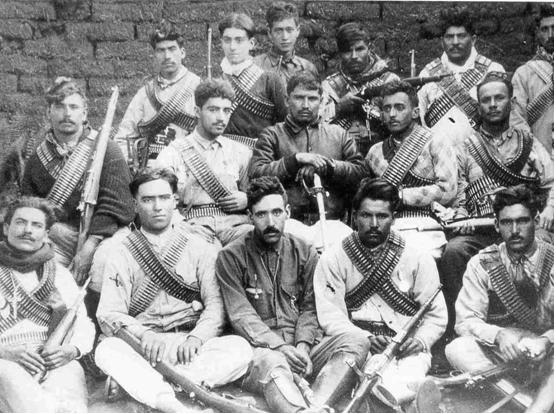

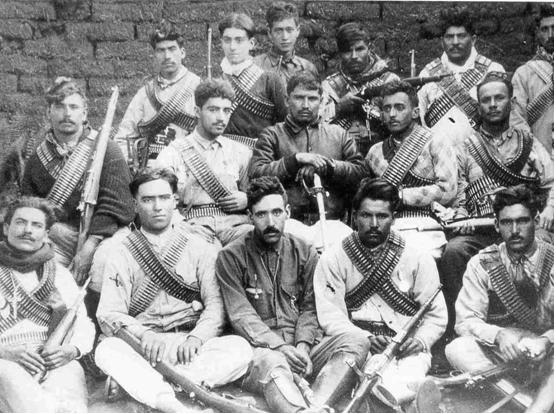

The formal rebellion began on January 1, 1927, with a manifesto sent by Garza, ''A la Nación'' ("To the Nation"). It declared that "the hour of battle has sounded" and that "the hour of victory belongs to God." With the declaration, the state of Jalisco, which had been seemingly quiet since the Guadalajara church uprising, exploded. Bands of rebels moving in the " Los Altos" region northeast of Guadalajara began seizing villages and were often armed with only ancient muskets and clubs. The rebels had scarce logistical supplies and relied heavily on the Feminine Brigades of St. Joan of Arc and raids on towns, trains, and ranches to supply themselves with money, horses, ammunition, and food. By contrast, the Calles government was supplied with arms and ammunition by the American government later in the war. In at least one battle, American pilots provided air support for the federal army against the Cristero rebels.

The Calles government failed at first to take the threat seriously. The rebels did well against the ''agraristas'', a rural militia recruited throughout Mexico, and the Social Defense forces, the local militia, but were at first always defeated by regular federal troops, who guarded the main cities. The federal army then had 79,759 men. When the Jalisco federal commander, General Jesús Ferreira, moved in on the rebels, he matter-of-factly wired to army headquarters that "it will be less a campaign than a hunt."Jim TuckThe Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico's Cristero Rebellion

p. 55, University of Arizona Press, 1982 That sentiment was held also by Calles.

However, the rebels planned their battles fairly well considering that most of them had little to no previous military experience. The most successful rebel leaders were Jesús Degollado, a pharmacist;

However, the rebels planned their battles fairly well considering that most of them had little to no previous military experience. The most successful rebel leaders were Jesús Degollado, a pharmacist; Victoriano Ramírez

Victoriano Ramírez López (April 13, 1888 in San Miguel el Alto, Jalisco – March 17, 1929 in Tepatitlan, Jalisco), also known as "El Catorce" (The Fourteen), was a Mexican General of the Cristero War known for his excellent combat skill ...

, a ranch hand; and two priests, Aristeo Pedroza and José Reyes Vega

José Reyes Vega was a Mexican priest who participated in the Cristero War as a general. He was known as "Father Vega".

On April 19, 1927, an event took place that almost succeeded in extinguishing the revolution. He led a raid against a trai ...

. Reyes Vega was renowned, and Cardinal Davila deemed him a "black-hearted assassin."Jim TuckThe Anti-clerical Who Led a Catholic Rebellion

Latin American Studies At least five priests took up arms, and many others supported them in various ways. Many of the rebel peasants who took up arms in the fight had different motivations from the Catholic Church. Many were still fighting for agrarian

land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

, which had been years earlier the focal point of the Mexican Revolution. The peasantry was still upset of the usurpation of its rightful title to the land.

The Mexican episcopate never officially supported the rebellion, but the rebels had some indications that their cause was legitimate. Bishop José Francisco Orozco of Guadalajara remained with the rebels. Although he formally rejected armed rebellion, he was unwilling to leave his flock.

On February 23, 1927, the Cristeros defeated federal troops for the first time at

On February 23, 1927, the Cristeros defeated federal troops for the first time at San Francisco del Rincón

San Francisco del Rincón is a city and municipality in the western part of the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. The city serves as the municipal seat for the municipality of San Francisco del Rincón. The city lies at the extreme northwest corner of t ...

, Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, followed by another victory at San Julián, Jalisco. However, they quickly began to lose in the face of superior federal forces, retreated into remote areas, and constantly fled federal soldiers. Most of the leadership of the revolt in the state of Jalisco was forced to flee to the U.S. although Ramírez and Vega remained.

In April 1927, the leader of the civilian wing of the Cristiada, Anacleto González Flores

Anacleto González Flores (July 13, 1888 – April 1, 1927) was a Mexican Catholic layman and lawyer who was tortured and executed during the persecution of the Catholic Church under Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles.

González was beat ...

, was captured, tortured, and killed. The media and the government declared victory, and plans were made for a re-education campaign in the areas that had rebelled. As if to prove that the rebellion was not extinguished and to avenge his death, Vega led a raid against a train carrying a shipment of money for the Bank of Mexico

The Bank of Mexico ( es, Banco de México), abbreviated ''BdeM'' or ''Banxico,'' is Mexico's central bank, monetary authority and lender of last resort. The Bank of Mexico is autonomous in exercising its functions, and its main objective is to ac ...

on April 19, 1927. The raid was a success, but Vega's brother was killed in the fighting.

The "concentration" policy, rather than suppressing the revolt, gave it new life, as thousands of men began to aid and join the rebels in resentment for their treatment by the government. When rains came, the peasants were allowed to return to the harvest, and there was now more support than ever for the Cristeros. By August 1927, they had consolidated their movement and had begun constant attacks on federal troops garrisoned in their towns. They would soon be joined by Enrique Gorostieta

Enrique Gorostieta Velarde ( Monterrey, 1889 – Atotonilco el Alto, June 2, 1929) was a Mexican soldier best known for his leadership as a general during the Cristero War.

Life

Born in Monterrey into a prominent Mexican-Basque family, Enrique G ...

, a retired general hired by the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty

National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty ( es, Liga Nacional Defensora de la Libertad Religiosa – LNDLR) was a Mexican Catholic religious civil rights organization formed in March 1925 that played a crucial role in the Cristero War ...

. Although Gorostieta was originally a liberal and a skeptic, he eventually wore a cross around his neck and speak openly of his reliance on God.

On June 21, 1927, the first Women's Brigade was formed in Zapopan

Zapopan () is a city and municipality located in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Part of the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area, the population of Zapopan city proper makes it the second largest city in the state, very close behind the population of ...

. It began with 16 women and one man, but after a few days, it grew to 135 members and soon came to number 17,000. Its mission was to obtain money, weapons, provisions, and information for the combatant men and to care for the wounded. By March 1928, some 10,000 women were involved in the struggle, with many smuggling weapons into combat zones by carrying them in carts filled with grain or cement. By the end of the war, it numbered some 25,000.

With close ties to the Church and the clergy, the De La Torre family was instrumental in bringing the Cristero Movement to northern Mexico. The family, originally from Zacatecas and Guanajuato, moved to Aguascalientes and then, in 1922, to San Luis Potosí. It moved again to Tampico for economic reasons and finally to Nogales (both the Mexican city and its similarly named sister city across the border in Arizona) to escape persecution from authorities because of its involvement in the Church and the rebels.

The Cristeros maintained the upper hand throughout 1928, and in 1929, the government faced a new crisis: a revolt within army ranks that was led by Arnulfo R. Gómez in Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. The Cristeros tried to take advantage by a failed attack on Guadalajara in late March 1929. The rebels managed to take Tepatitlán

Tepatitlán de Morelos is a city and municipality founded in 1530, in the central Mexican state of Jalisco. It is located in the area known as Los Altos de Jalisco (the 'Highlands of Jalisco'), about 70 km east of state capital Guadalajara, ...

on April 19, but Vega was killed. The rebellion was met with equal force, and the Cristeros were soon facing divisions within their own ranks.

Another difficulty facing the Cristeros and especially the Catholic Church was the extended period without a place of worship. The clergy faced the fear of driving away the faithful masses by engaging in war for so long. They also lacked the overwhelming sympathy or support from many aspects of Mexican society, even among many Catholics.

Diplomacy

In October 1927, the American ambassador,

In October 1927, the American ambassador, Dwight Morrow

Dwight Whitney Morrow (January 11, 1873October 5, 1931) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician, best known as the U.S. ambassador who improved U.S.-Mexican relations, mediating the religious conflict in Mexico known as the Cristero ...

, initiated a series of breakfast meetings with Calles at which they would discuss a range of issues from the religious uprising to oil and irrigation. That earned him the nickname "the ham and eggs diplomat" in U.S. papers. Morrow wanted the conflict to end for regional security and to help find a solution to the oil problem in the U.S. He was aided in his efforts by Father John J. Burke John J. Burke (1875–1936) was a Paulist priest and editor of the Catholic World from 1903 to 1922.

A central point of Burke's writing and lecturing concerned the supernatural element of charity. Burke told the 1915 graduating class of New York's ...

of the National Catholic Welfare Conference The National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) was the annual meeting of the American Catholic hierarchy and its standing secretariat; it was established in 1919 as the successor to the emergency organization, the National Catholic War Council.

It co ...

. Calles's term as president was coming to an end, and ex-President Álvaro Obregón

Álvaro Obregón Salido (; 17 February 1880 – 17 July 1928) better known as Álvaro Obregón was a Sonoran-born general in the Mexican Revolution. A pragmatic centrist, natural soldier, and able politician, he became the 46th President of Me ...

had been elected president and was scheduled to take office on December 1, 1928. Obregón had been more lenient to Catholics during his time in office than Calles, but it was also generally accepted among Mexicans, including the Cristeros, that Calles was his puppet leader

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sovere ...

. Two weeks after his election, Obregón was assassinated by a Catholic radical, José de León Toral

José de León Toral (December 23, 1900 – February 9, 1929) was a Roman Catholic who assassinated General Álvaro Obregón, then- president elect of Mexico, in 1928.

Early life

León Toral was born in Matehuala, San Luis Potosí, into a f ...

, which gravely damaged the peace process.

In September 1928, Congress named

In September 1928, Congress named Emilio Portes Gil

Emilio Cándido Portes Gil (; 3 October 1890 – 10 December 1978) was President of Mexico from 1928 to 1930, one of three to serve out the six-year term of President-elect General Álvaro Obregón, who had been assassinated in 1928. Since the ...

as interim president with a special election to be held in November 1929. Portes was more open to the Church than Calles had been and allowed Morrow and Burke to restart the peace initiative. Portes told a foreign correspondent on May 1, 1929, that "the Catholic clergy, when they wish, may renew the exercise of their rites with only one obligation, that they respect the laws of the land." The next day, the exiled Archbishop Leopoldo Ruíz y Flores issued a statement that the bishops would not demand the repeal of the laws but only their more lenient enforcement.

Morrow managed to bring the parties to agreement on June 21, 1929. His office drafted a pact called the ''arreglos'' ("agreement"), which allowed worship to resume in Mexico and granted three concessions to the Catholics. Only priests who were named by hierarchical superiors would be required to register; religious instruction in churches but not in schools would be permitted; and all citizens, including the clergy, would be allowed to make petitions to reform the laws. However, the most important parts of the agreement were that the Church would recover the right to use its properties, and priests would recover their rights to live on the properties. Legally speaking, the Church was not allowed to own real estate, and its former facilities remained federal property. However, the Church effectively took control over the properties. In the convenient arrangement for both parties, the Church ostensibly ended its support for the rebels.

Morrow managed to bring the parties to agreement on June 21, 1929. His office drafted a pact called the ''arreglos'' ("agreement"), which allowed worship to resume in Mexico and granted three concessions to the Catholics. Only priests who were named by hierarchical superiors would be required to register; religious instruction in churches but not in schools would be permitted; and all citizens, including the clergy, would be allowed to make petitions to reform the laws. However, the most important parts of the agreement were that the Church would recover the right to use its properties, and priests would recover their rights to live on the properties. Legally speaking, the Church was not allowed to own real estate, and its former facilities remained federal property. However, the Church effectively took control over the properties. In the convenient arrangement for both parties, the Church ostensibly ended its support for the rebels.

Over the previous two years, anticlerical officers, who were hostile to the federal government for reasons other than its position on religion, had joined the rebels. When the agreement between the government and the Church was made known, only a minority of the rebels went home, mainly those who felt their battle had been won. On the other hand, since the rebels themselves had not been consulted in the talks, many felt betrayed, and some continued to fight. The Church threatened those rebels with excommunication and the rebellion gradually died out. The officers, fearing that they would be tried as traitors, tried to keep the rebellion alive. Their attempt failed, and many were captured and shot, and others escaped to

Over the previous two years, anticlerical officers, who were hostile to the federal government for reasons other than its position on religion, had joined the rebels. When the agreement between the government and the Church was made known, only a minority of the rebels went home, mainly those who felt their battle had been won. On the other hand, since the rebels themselves had not been consulted in the talks, many felt betrayed, and some continued to fight. The Church threatened those rebels with excommunication and the rebellion gradually died out. The officers, fearing that they would be tried as traitors, tried to keep the rebellion alive. Their attempt failed, and many were captured and shot, and others escaped to San Luis Potosí

San Luis Potosí (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of San Luis Potosí ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de San Luis Potosí), is one of the 32 states which compose the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 58 municipalities and i ...

, where General Saturnino Cedillo

Saturnino Cedillo Martínez (November 29, 1890 in Ciudad del Maíz, San Luis Potosí - January 11, 1939 in Sierra Ventana, San Luis Potosí) was a Mexican politician who participated in the Mexican Revolution and the Cristero War. He was governor ...

gave them refuge.

The war had claimed the lives of some 90,000 people: 56,882 federals, 30,000 Cristeros, and numerous civilians and Cristeros who were killed in anticlerical raids after the war had ended. As promised by Portes Gil, the Calles Law remained on the books, but there were no organized federal attempts to enforce it. Nonetheless, in several localities, officials continued persecution of Catholic priests, based on their interpretation of the law.

In 1992, the Mexican government amended the constitution by granting all religious groups legal status, conceding them property rights, and lifting restrictions on the number of priests in the country.Roberto Blancarte, “Recent Changes in Church-State Relations in Mexico: An Historical Approach.” ''Journal of Church & State'', Autumn 1993, vol. 35. No. 4.

American involvement

Knights of Columbus

American councils and Mexican councils, mostly newly formed, of theKnights of Columbus

The Knights of Columbus (K of C) is a global Catholic fraternal service order founded by Michael J. McGivney on March 29, 1882. Membership is limited to practicing Catholic men. It is led by Patrick E. Kelly, the order's 14th Supreme Knight. ...

, both opposed the persecution by the Mexican government. So far, nine of those who were beatified or canonized were Knights. The American Knights collected more than $1 million in order to assist exiles from Mexico, fund the continuation of the education of expelled seminarians, and inform U.S. citizens about the oppression.The Story, Martyrs, and Lessons of the Cristero War: An interview with Ruben Quezada about the Cristiada and the bloody Cristero War (1926–1929)Catholic World Report, June 1, 2012 They circulated five million leaflets about the war in the United States, held hundreds of lectures, spread the news via radio, and paid to "smuggle" a friendly journalist into Mexico so he could cover the war for an American audience. In addition to lobbying the American public, the Knights met United States President

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

and pressed him for US intervention on behalf of the rebels.

According to former Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus, Carl A. Anderson, two thirds of Mexican Catholic councils were shut down by the Mexican government. In response, the Knights of Columbus published posters and magazines which presented Cristero soldiers in a positive light.

Ku Klux Klan

In the mid-1920s, high-ranking members of theanti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its Hierarchy of the Catholic Church, clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestantism, Protestant states, ...

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

offered Calles $10,000,000 in order to aid him in his war against the Catholic insurgents, but there is no evidence that the Klan's offer was accepted.

Aftermath

Blood-Drenched Altars

Faith & Reason 1994 Catholics continued to oppose Calles's insistence on a state monopoly on education, which suppressed Catholic education and introduced secular education in its place: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth." Calles's military persecution of Cristeros after the truce would be officially condemned by Mexican President

Lázaro Cárdenas

Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (; 21 May 1895 – 19 October 1970) was a Mexican army officer and politician who served as president of Mexico from 1934 to 1940.

Born in Jiquilpan, Michoacán, to a working-class family, Cárdenas joined the M ...

and the Mexican Congress in 1935. Between 1935 and 1936, Cárdenas had Calles and many of his close associates arrested and forced them into exile soon afterwards. Freedom of worship was no longer suppressed, but some states refused to repeal Calles's policy. Relations with the Church improved under President Cárdenas.

The government's disregard for the Church, however, did not relent until 1940, when President Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho (; 24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955) was a Mexican politician and military leader who served as the President of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Despite participating in the Mexican Revolution and achieving a high rank, he cam ...

, a practicing Catholic, took office. During Cárdenas presidency, Church buildings in the country continued in the hands of the Mexican government, and the nation's policies regarding the Church still fell into federal jurisdiction. Under Camacho, bans against Church anticlerical laws were no longer enforced anywhere in Mexico.''Sarasota Herald-Tribune'', "Mexico Fails To Act on Church Law", February 19, 1951

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934, at least 40 priests were killed. There were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, but by 1934, there were only 334 licensed by the government to serve 15 million Catholics. The rest had been eliminated by emigration, expulsion, assassination, or not obtaining licenses. In 1935, 17 states had no registered priests.

The end of the Cristero War affected emigration to the United States. "In the aftermath of their defeat, many of the Cristeros – by some estimates as much as 5 percent of Mexico's population – fled to the United States. Many of them made their way to Los Angeles, where they were received by John Joseph Cantwell

John Joseph Cantwell (December 1, 1874 – October 30, 1947) was an Irish-born American prelate of the Catholic Church. He led the Archdiocese of Los Angeles from 1917 until his death in 1947, becoming its first archbishop in 1936. Cantwell w ...

, bishop of what was then the Los Angeles-San Diego diocese." Under Archbishop Cantwell's sponsorship, the Cristero refugees became a substantial community in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, in 1934 staging a parade some 40,000-strong throughout the city. Additionally, several other cites such as Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and San Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

and other cities saw in an increase in Mexican Catholics fleeing because of the war.

Cárdenas era

The Calles Law was repealed after Cárdenas became president in 1934. Cárdenas earned respect from Pope Pius XI and befriended Mexican Archbishop Luis María Martínez, a major figure in Mexico's Catholic Church who successfully persuaded Mexicans to obey the government's laws peacefully. The Church refused to back Mexican insurgent Saturnino Cedillo's failed revolt against Cárdenas although Cedillo endorsed more power for the Church. Cárdenas's government continued to suppress religion in the field of education during his administration. The Mexican Congress amended Article 3 of the Constitution in October 1934 to include the following introductory text: "The education imparted by the State shall be a socialist one and, in addition to excluding all religious doctrine, shall combat fanaticism and prejudices by organizing its instruction and activities in a way that shall permit the creation in youth of an exact and rational concept of the Universe and of social life." The implementation of socialist education met with strong opposition in some parts of academia and in areas that had been controlled by the Cristeros. PopePius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City from ...

also published the encyclical ''Firmissimam constantiam'' on March 28, 1937, expressing his opposition to the "impious and corruptive school" (paragraph 22) and his support for Catholic Action

Catholic Action is the name of groups of lay Catholics who advocate for increased Catholic influence on society. They were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic countries under anti-clerical regimes such as Spain, Ita ...

in Mexico. That was the third and last encyclical published by Pius XI that referred to the religious situation in Mexico. The amendment was ignored by President Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho (; 24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955) was a Mexican politician and military leader who served as the President of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Despite participating in the Mexican Revolution and achieving a high rank, he cam ...

and was officially repealed from the Constitution in 1946. Constitutional bans against the Church would not be enforced anywhere in Mexico during Camacho's presidency.

Cristeros' violence against school teachers

Many former Cristeros took up arms again and fought as independent rebels and some Catholics joined them. They targeted unarmed public school teachers who implemented secular education and committed atrocities against them. Government supporters blamed the atrocities on the Cristeros in general. Some of the teachers who were paid by the government refused to leave their schools and communities, and as a result, they sustained mutilations when Cristeros cut their ears off. Thus, the teachers who were murdered during the conflict are frequently referred to as ''maestros desorejados'' ("teachers without ears"). In some cases, teachers were tortured and killed by former Cristero rebels. It is calculated that approximately 300 rural teachers were killed between 1935 and 1939, and other authors calculate that at least 223 teachers were victims of the violence which occurred between 1931 and 1940, the acts of violence which occurred during this period included the assassinations of Carlos Sayago, Carlos Pastraña, and Librado Labastida inTeziutlán

Teziutlán is a city in the northeast of the Mexican state of Puebla. Its 2005 census population was 60,597. It also serves as the municipal seat for the surrounding Teziutlán Municipality. The municipality has an area of 84.2 km2 (32.51 ...

, Puebla, the hometown of President Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho (; 24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955) was a Mexican politician and military leader who served as the President of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Despite participating in the Mexican Revolution and achieving a high rank, he cam ...

; the execution of a teacher, Carlos Toledano, who was burned alive in Tlapacoyan, Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

; and the lynching of at least 42 teachers in the state of Michoacán

Michoacán, formally Michoacán de Ocampo (; Purépecha: ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Michoacán de Ocampo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of ...

.

The Mexican bishops fearing that they could be blamed for the attacks and punished, formed a lay group called Las Legiones, which would infiltrate these independent rebel groups and remove people responsible for the violence against civilians from their ranks. This style of infiltration is rumored to have influenced the tactics of the Legion of Christ

The Congregation of the Legionaries of Christ ( la, Congregatio Legionariorum Christi; abbreviated LC; also Legion of Christ) is a Roman Catholic clerical religious order made up of priests and candidates for the priesthood established by Marci ...

.

Cristero War saints

The Catholic Church has recognized several of those who were killed in the Cristero War as

The Catholic Church has recognized several of those who were killed in the Cristero War as martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

s, including Miguel Pro

José Ramón Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez, also known as Blessed Miguel Pro, SJ (January 13, 1891 – November 23, 1927) was a Mexican Jesuit priest executed under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles on the false charges of bombing and att ...

, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

who was shot dead without trial by a firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are us ...

on November 23, 1927, for his alleged involvement in an assassination attempt against former President Álvaro Obregón

Álvaro Obregón Salido (; 17 February 1880 – 17 July 1928) better known as Álvaro Obregón was a Sonoran-born general in the Mexican Revolution. A pragmatic centrist, natural soldier, and able politician, he became the 46th President of Me ...

, though his supporters maintained that he was executed for carrying out his priestly duties in defiance of the government. His beatification

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

occurred in 1988.

On May 21, 2000, Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

canonized a group of 25 martyrs who were killed during the Cristero War.Gerzon-Kessler, Ari"Cristero Martyrs, Jalisco Nun To Attain Sainthood"

. ''Guadalajara Reporter''. May 12, 2000 They had been beatified on November 22, 1992. Of this group, 22 were

secular clergy

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. A secular priest (sometimes known as a diocesan priest) is a priest who commits themselves to a certain geogra ...

, and three were laymen. They did not take up arms but refused to leave their flocks and ministries and were shot or hanged by government forces for offering the sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

. Most were executed by federal forces. Although Pedro de Jesús Maldonado was killed in 1937, after the war ended, he is considered a member of the Cristeros.

The Catholic Church recognized 13 additional victims of the War as martyrs on November 20, 2005, thus paving the way for their beatifications."14-year-old Mexican martyr to be beatified Sunday"; ''Catholic News Agency''; November 5, 2005 This group was mostly lay people, including Luis Magaña Servín and 14-year-old

José Sánchez del Río

José Luis Sánchez del Río (March 28, 1913 – February 10, 1928) was a Mexican Cristero who was put to death by government officials because he refused to renounce his Catholic faith. His death was seen as a largely political venture on the p ...

. On November 20, 2005, at Jalisco Stadium in Guadalajara, José Saraiva Cardinal Martins celebrated the beatifications. Furthermore some religious relics have been brought to the United States from Jalisco and are currently located at Our Lady of the Mount Church in Cicero, Illinois.

Other views

The Mexican historian and researcherJean Meyer

Jean Meyer Barth (born February 8, 1942) is a French-Mexican historian and author, known for his writings on early 20th-century Mexican history. He has published extensively on the Mexican Revolution and Cristero War, the history of Nayarit, and ...

argues that the Cristero soldiers were peasants who tried to resist the heavy pressures of the modern bourgeois state, the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, the city elites, and the rich, all of whom wanted to suppress the Catholic faith.

In popular culture

''For Greater Glory

''For Greater Glory: The True Story of Cristiada'', also known as ''Cristiada'' and as ''Outlaws'', is a 2012 Epic film, epic historical war film, war drama film Young, James"''Cristiada'' welcomed in Durango" August 21, 2010, ''Variety'' direct ...

'' is a 2012 film based on the events of the Cristero War.

Many films, shorts, and documentaries about the war have been produced since 1929 such as the following:

* '' Cristiada'' (aka ''For Greater Glory

''For Greater Glory: The True Story of Cristiada'', also known as ''Cristiada'' and as ''Outlaws'', is a 2012 Epic film, epic historical war film, war drama film Young, James"''Cristiada'' welcomed in Durango" August 21, 2010, ''Variety'' direct ...

'') (2012).

Several ballads ''corridos'' were composed in the period of the war by federal troops and Cristeros.

See also

*Calles Law

The Calles Law (), or Law for Reforming the Penal Code (''ley de tolerancia de cultos'', "law of worship tolerance"), was a statute enacted in Mexico in 1926, under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles, to enforce restrictions against the Ca ...

* Catholic Church in Latin America

The Catholic Church in Latin America began with the Spanish colonization of the Americas and continues up to the present day.

In the later part of the 20th century, however, the rise of Liberation theology has challenged such close alliances betwe ...

* Catholic Church in Mexico

, native_name_lang =

, image = Catedral_de_México.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt =