Cotton States And International Exposition (1895) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

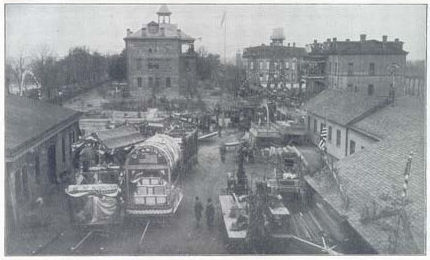

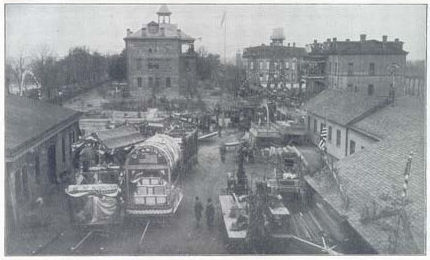

The Cotton States and International Exposition was a world's fair held in

Text of Atlanta Compromise Speech

/ref>

Fred L. Howe 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition Photographs

from the

Cotton States Exposition of 1895

historical marker {{DEFAULTSORT:Cotton States And International Exposition World's fairs in Georgia (U.S. state) 1895 in the United States 1895 in Georgia (U.S. state) 19th century in Atlanta Festivals established in 1895

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, United States in 1895. The exposition was designed "to foster trade between southern states and South American nations as well as to show the products and facilities of the region to the rest of the nation and Europe."

The Cotton States and International Exposition featured exhibits from six states, including various innovations in agriculture and technology, and exhibits about women and African Americans. President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

presided over the opening of the exposition remotely by flipping an electric switch from his house in Massachusetts on September 18, 1895.

The event is best remembered for the "Atlanta Compromise" speech given by Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

on September 18, promoting racial cooperation.

Background

The idea for aninternational exposition

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

in Atlanta was first proposed in November 1893 by William Hemphill

William Arnold Hemphill (May 5, 1842 – August 17, 1902) was an American businessman and politician who served as Mayor of Atlanta from 1891 to 1893.

Biography Early years and education

Hemphill was born on May 5, 1842, in Athens, Georgia. He at ...

, a former mayor of Atlanta .. Hemphill served as the vice president and director of the exposition.

Bradford Lee Gilbert

Bradford Lee Gilbert (March 24, 1853 – September 1, 1911) was a nationally active American architect based in New York City. He is known for designing the Tower Building in 1889, the first steel-framed building anywhere and the first skysc ...

was the supervising architect for the exposition. He designed the Administration Building with the Main Entrance and Exits, the Agricultural Building, the Auditorium, the Chime Tower and Band Stand, the Electricity Building, the Fire Building, the Machinery Hall, the Manufacturers & Liberal Arts Building, the Minerals and Forestry Building, the Negro Building, the Semi-Circular Entrance and Exit Gateway, the Transportation Building, and the United States Government Building.

The grounds were designed by Joseph Forsyth Johnson

Joseph Forsyth Johnson (1840 – 17 July 1906) was an English landscape architect and disciple of John Ruskin.

. Over $2,000,000 was spent transforming the exhibition site. A pond was expanded to Lake Clara Meer for the event. Tropical gardens, now known as the Atlanta Botanical Garden, were also constructed for the fair.

The government allocated $250,000 for the construction of a government building. Many states and countries such as Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

also had their buildings.

The Exposition was open for 100 days, beginning on September 18, 1895, and ending on December 31, 1895. It attracted nearly 800,000 visitors from the United States and thirteen countries. However, the exposition was plagued by financial issues.

Exhibits

Walter McElreath

Walter McElreath (July 17, 1867 – December 6, 1951) was an American lawyer, legislator, bank executive, and author in Atlanta, Georgia. McElreath was a member of the Georgia House of Representatives from 1909 until 1912. He was one of the founde ...

described the fair in his memoirs: "The railroad yards were jammed every morning with trains that brought enormous crowds. The streets were crowded all day long. Every conceivable kind of fakir

Fakir ( ar, فقیر, translit=faḳīr or ''faqīr'') is an Islamic term traditionally used for Sufi Muslim ascetics who renounce their worldly possessions and dedicate their lives to the worship of God. They do not necessarily renounce al ...

bartered his wares. Dime museums flourished on every street...Vast stucco hotels stood on Fourteenth Street...I spent a great deal of time on the streets looking at the strange crowds—American Indians, Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia in ...

, Hindus, Japanese, and people from every corner of the globe -- who had come as professional midway entertainers or fakirs."

The exposition included many exhibits on Minerals and Forestry, Agriculture, Food and Accessories, Machinery and Appliances, Horticulture, Machinery, Manufacturers, Electricity, Fine Arts, Painting and Sculpture, Liberal Arts, Education, and Literature. About 6,000 exhibits were examined by the Award Committee. The Awards Committee awarded a total of 1,573 medals: 634 gold medals, 444 silver medals, and 495 bronze medals.

In late September Charles Francis Jenkins

Charles Francis Jenkins (August 22, 1867 – June 6, 1934) was an American engineer who was a pioneer of early cinema and one of the inventors of television, though he used mechanical rather than electronic technologies. His businesses incl ...

demonstrated an early movie projector called the "Phantoscope

The Phantoscope was a film projection machine, a creation of Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. In the early 1890, Jenkins began creating the projector. He later met Thomas Armat, who provided financial backing and assisted with necessary m ...

." Organist and composer Fannie Morris Spencer

Fannie Morris Spencer (August 15, 1865 - April 9, 1943) was an American composer and organist who wrote a collection of 32 hymns and was a founding member of the American Guild of Organists.

Spencer was born in Newburgh, New York, to Cynthia McCo ...

chaired the exposition’s music committee. John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa ( ; November 6, 1854 – March 6, 1932) was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic era known primarily for American military marches. He is known as "The March King" or the "American March King", to dist ...

composed his famous march, "King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

", for the exposition and dedicated it to the people of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

.

December 26, 1895, was Negro Day at the exposition. Famed African American quilter Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers (October 29, 1837 – January 1, 1910) was an American folk artist and quilter. Born into slavery in rural northeast Georgia, she married young and had a large family. After the American Civil War and emancipation, she and her hus ...

attended this day and met with Irvine Garland Penn

Irvine Garland Penn (October 7, 1867 – July 22, 1930) was an educator, journalist, and lay leader in the Methodist Episcopal church in the United States. He was the author of ''The Afro-American Press and Its Editors'', published in 1891, and a ...

, the chief of the Negro Building.

The National League of Mineral Painters, with Adelaïde Alsop Robineau

Adelaide Alsop Robineau (1865–1929) was an American china painter and potter, and is considered one of the top ceramists of American art pottery in her era.

Early life and education

Adelaide Alsop was born in 1865 in Middletown, Connecticut. Sh ...

and Mary Chase Perry

Mary Chase Perry Stratton (March 15, 1867 – April 15, 1961) was an American ceramic artist. She was a co-founder, along with Horace James Caulkins, of Pewabic Pottery, a form of ceramic art used to make architectural tiles.

Biography

Strat ...

, contributed decorative objects and artwork to the New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

exhibit.

Women's Building

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

's first woman American architect

This list of American architects includes notable architects and architecture firms with a strong connection to the United States (i.e., born in the United States, located in the United States or known primarily for their work in the United States ...

, Elise Mercur

Elise Mercur, also known as Elise Mercur Wagner, (November 30, 1864 – March 27, 1947) was Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania's first woman architect. She was raised in a prominent family and educated abroad in France and Germany before completing train ...

(1864–1947) designed the Palladian style

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

Woman's Building. The Women's Building showcased accomplishments of women throughout the South, and the country, in the areas of education, health care, and the fine and decorative arts. Its exhibitions were curated by women from Georgia. The contents were contributed by women around the country. Women culled historical artifacts, decorative arts objects, and industrial products to compose displays in each room, including the Baltimore Room, the Lucy Cobb Room, Mary Ball Washington

Mary Washington (; born sometime between 1707 and 1709 – August 25, 1789), was the second wife of Augustine Washington, a planter in Virginia, the mother-in-law of Martha Washington, the paternal grandmother of Bushrod Washington, and ...

Tea Room, the Columbus Room, Model Library, Assembly Hall, and others, each assigned to a different state. The many elaborate displays reflected a diversity of views spanning the mainstream social and domestic roles of Southern women, such as patriotism and the ideals of traditional motherhood to little-known achievements of women counter to mainstream stereotypes.

The Legion of Loyal Women display presented an arrangement of 45 dolls, each one adorned with a small shield showing the name of a state, to illustrate the American Patriotic salute. Other displays posed a challenge to the roles of women and other social conventions. The Colonial Room presented utensils and furnishings, as well as Dolly Madison

Dolly Madison is an American bakery brand owned by Hostess Brands, selling packaged baked snack foods. It is best known for its long marketing association with the ''Peanuts'' animated TV specials.

History

In 1937, Ralph Leroy Nafziger started ...

's spectacles, a gun carried in the Battle of Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

, and brass medallions belonging to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

; the display was said to represent ''"the growing bond of cooperation between the North and South."''

The exposition introduced new ideas to foster trade and collaboration between the Southern and Northern states and to also show ideas, products, and facilities to the rest of the nation and to Europe. The exhibitions presented prototypes for a hospital room, a nursery, a kindergarten classroom, and a model library—each one in working order. These functional rooms represented the environments where women played important roles outside the home and family, and were equipped with the most up-to-date equipment, features, and furnishings. The model library included a collection of publications by women authors from every state in the nation. A photography exhibition featured portraits of women in every branch of literature, appended with a verse, letter, or section of a manuscript by the authors.

Booker T. Washington's speech

On September 18, 1895, Booker T. Washington gave the "Atlanta Compromise" speech was anaddress

An address is a collection of information, presented in a mostly fixed format, used to give the location of a building, apartment, or other structure or a plot of land, generally using political boundaries and street names as references, along w ...

on the topic of race relations

Race relations is a sociological concept that emerged in Chicago in connection with the work of sociologist Robert E. Park and the Chicago race riot of 1919. Race relations designates a paradigm or field in sociology and a legal concept in the ...

. Washington's speech laid the foundation for the Atlanta Compromise, an agreement between African American leaders and Southern white leaders in which blacks would work meekly and submit to white political rule, while whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic education and due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

of law. The speech was presented before a predominantly white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

audience and has been recognized as one of the most important, influential, and controversial speeches in American history./ref>

Legacy

The Cotton States Exposition successfully showcased Atlanta as a business center and attracted investment to the city. After the exposition, the grounds were purchased by the City of Atlanta and becamePiedmont Park

Piedmont Park is an urban park in Atlanta, Georgia, located about northeast of Downtown, between the Midtown and Virginia Highland neighborhoods. Originally the land was owned by Dr. Benjamin Walker, who used it as his out-of-town gentleman's ...

and the Atlanta Botanical Garden

The Atlanta Botanical Garden is a botanical garden located adjacent to Piedmont Park in Midtown Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Incorporated in 1976, the garden's mission is to "develop and maintain plant collections for the purposes of display, ...

. The buildings were demolished, but the park grounds remain largely as Joseph Forsyth Johnson

Joseph Forsyth Johnson (1840 – 17 July 1906) was an English landscape architect and disciple of John Ruskin.

designed it for the exposition. However, the stone balustrades

A baluster is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its cons ...

scattered around the park are the only remaining part of the enormous main building.

References

Further reading

* * Perdue, Theda. ''Race and the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition of 1895'' (2010). * Cardon, Nathan. "The South's 'New Negroes' and African American Visions of Progress at the Atlanta and Nashville International Expositions, 1895-1897" ''Journal of Southern History'' (2014). * Cardon, Nathan. ''A Dream of the Future: Race, Empire, and Modernity at the Atlanta and Nashville World's Fairs'' (Oxford University Press, 2018).External links

Fred L. Howe 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition Photographs

from the

Atlanta History Center

Atlanta History Center is a history museum and research center located in the Buckhead district of Atlanta, Georgia. The Museum was founded in 1926 and currently consists of nine permanent, and several temporary, exhibitions. Atlanta History Cen ...

Cotton States Exposition of 1895

historical marker {{DEFAULTSORT:Cotton States And International Exposition World's fairs in Georgia (U.S. state) 1895 in the United States 1895 in Georgia (U.S. state) 19th century in Atlanta Festivals established in 1895