Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(now Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

).

Celebrations took place across the Commonwealth realms and a commemorative medal was issued. It has been the only British coronation to be fully televised; television cameras had not been allowed inside the abbey during her parents' coronation in 1937. Elizabeth's was the fourth and last British coronation of the 20th century. It was estimated to have cost £1.57 million (c. £43,427,400 in 2019).

Preparations

The one-day ceremony took 14 months of preparation: the first meeting of the Coronation Commission was in April 1952, under the chairmanship of the Queen's husband, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Other committees were also formed, such as the Coronation Joint Committee and the Coronation Executive Committee, both chaired by the Duke of Norfolk who, by convention as Earl Marshal, had overall responsibility for the event. Many physical preparations and decorations along the route were the responsibility of David Eccles, Minister of Works. Eccles described his role and that of the Earl Marshal: "The Earl Marshal is the producer – I am the stage manager..." The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent

Louis Stephen St. Laurent (''Saint-Laurent'' or ''St-Laurent'' in French, baptized Louis-Étienne St-Laurent; February 1, 1882 – July 25, 1973) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 12th prime minister of Canada from 19 ...

said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function." The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.

Norman Hartnell was commissioned by the Queen to design the outfits for all members of the royal family, including Elizabeth's coronation gown. His design for the gown evolved through nine proposals, and the final version resulted from his own research and numerous meetings with the Queen: a white silk dress embroidered with floral emblems of the countries of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

at the time: the Tudor rose of England, Scottish thistle, Welsh leek

The leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of ''Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek ( syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus ''Alli ...

, shamrock

A shamrock is a young sprig, used as a symbol of Ireland. Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, is said to have used it as a metaphor for the Christian Holy Trinity. The name ''shamrock'' comes from Irish (), which is the diminutive of ...

for Northern Ireland, wattle

Wattle or wattles may refer to:

Plants

*''Acacia sensu lato'', polyphyletic genus of plants commonly known as wattle, especially in Australia and South Africa

**''Acacia'', large genus of shrubs and trees, native to Australasia

**Black wattle, c ...

of Australia, maple leaf of Canada, the New Zealand silver fern, South Africa's protea, two lotus flowers

''Nelumbo nucifera'', also known as sacred lotus, Laxmi lotus, Indian lotus, or simply lotus, is one of two extant species of aquatic plant in the family Nelumbonaceae. It is sometimes colloquially called a water lily, though this more often re ...

for India and Ceylon, and Pakistan's wheat, cotton and jute

Jute is a long, soft, shiny bast fiber that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced from flowering plants in the genus ''Corchorus'', which is in the mallow family Malvaceae. The primary source of the fiber is ''Corchorus olit ...

. Roger Vivier created a pair of gold pumps for the occasion. The shoe featured jewel-encrusted heels and decorative motif on the upper sides, which was meant to resemble "the fleurs-de-lis pattern on the St Edward's Crown and the Imperial State Crown". Elizabeth chose to wear the Coronation necklace for the event. The piece was commissioned by Queen Victoria and worn by Queen Alexandra, Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022 ...

at their respective coronations. She paired it with the Coronation earrings.

Elizabeth rehearsed for the occasion with her maids of honour. A sheet was used in place of the velvet train, and a formation of chairs stood in for the carriage. She also wore the Imperial State Crown while going about her daily business – at her desk, during tea, and while reading a newspaper – so that she could become accustomed to its feel and weight. Elizabeth took part in two full rehearsals at Westminster Abbey, on 22 and 29 May, though some sources claim that she attended one or "several" rehearsals. The Duchess of Norfolk usually stood in for the Queen at rehearsals.

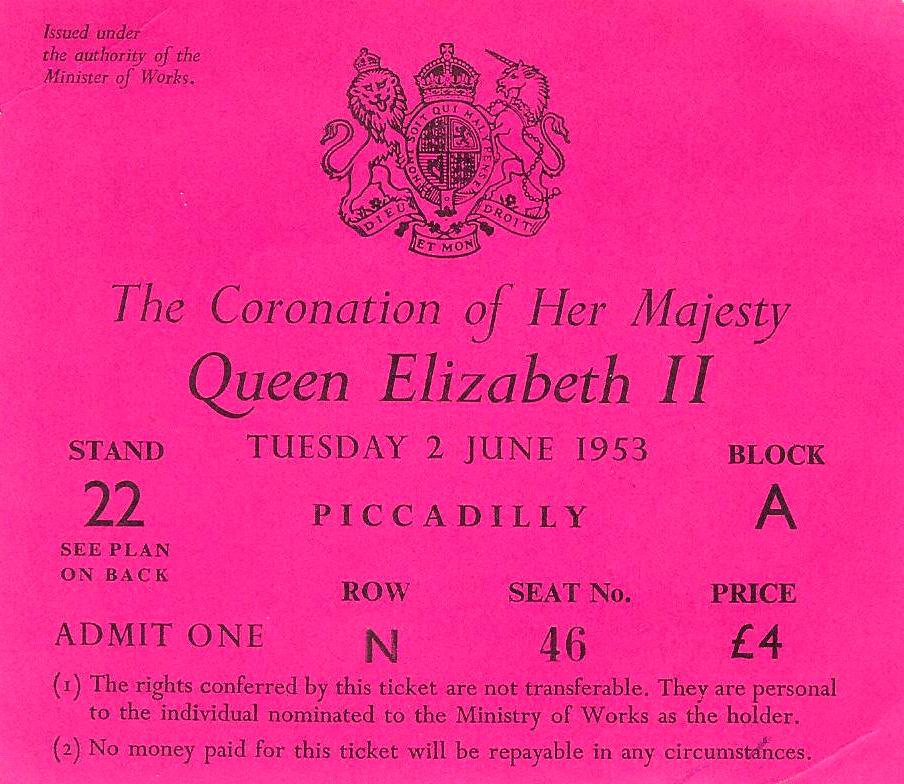

Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary had died on 24 March 1953, having stated in her will that her death should not affect the planning of the coronation, and the event went ahead as scheduled. It was estimated to cost £1.57 million (c£. in ), which included stands along the procession route to accommodate 96,000 people, lavatories, street decorations, outfits, car hire, repairs to the state coach, and alterations to the Queen's regalia.

Event

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

and clergy. However, for the new queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

Television

Millions across Britain watched the coronation live on theBBC Television Service

BBC Television is a service of the BBC. The corporation has operated a public broadcast television service in the United Kingdom, under the terms of a royal charter, since 1927. It produced television programmes from its own studios from 19 ...

, and many purchased or rented television sets for the event. The coronation was the first to be televised in full; the BBC's cameras had not been allowed inside Westminster Abbey for her parents' coronation in 1937, and had covered only the procession outside. There had been considerable debate within the British Cabinet on the subject, with Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

against the idea; Elizabeth refused his advice on this matter and insisted the event take place before television cameras, as well as those filming with experimental 3D technology

Stereoscopy (also called stereoscopics, or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the illusion of depth in an image by means of stereopsis for binocular vision. The word ''stereoscopy'' derives . Any stereoscopic image is ...

. The event was also filmed in colour, separately from the BBC's black and white television broadcast, where an average of 17 people watched each small TV.

Elizabeth's coronation was also the first major world event to be broadcast internationally on television.

In Europe, thanks to new relay links, this was the first live broadcast of an event taking place in the United Kingdom. The coronation was broadcast in France, Belgium, West Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, marking the birth of Eurovision

The Eurovision Song Contest (), sometimes abbreviated to ESC and often known simply as Eurovision, is an international songwriting competition organised annually by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), featuring participants representing pr ...

.

To make sure Canadians could see it on the same day, RAF Canberras flew BBC film recordings of the ceremony across the Atlantic Ocean to be broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the first non-stop flights between the United Kingdom and the Canadian mainland. At Goose Bay, Labrador, the first batch of film was transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) CF-100 jet fighter for the further trip to Montreal. In all, three such flights were made as the coronation proceeded, with the first and second Canberras taking the second and third batches of film, respectively, to Montreal. The following day, a film was flown west to Vancouver, whose CBC Television affiliate had yet to sign on. The film was escorted by the RCMP to the Peace Arch Border Crossing

The Peace Arch Border Crossing is the common name for the Blaine–Douglas crossing which connects the cities of Blaine, Washington and Surrey, British Columbia on the Canada–United States border. I5 on the American side joins BC Highway 99 ...

, where it was then escorted by the Washington State Patrol to Bellingham, where it was shown as the inaugural broadcast of KVOS-TV, a new station whose signal reached into the Lower Mainland

The Lower Mainland is a geographic and cultural region of the mainland coast of British Columbia that generally comprises the regional districts of Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley. Home to approximately 3.05million people as of the 2021 Canadia ...

of British Columbia, allowing viewers there to see the coronation as well, though on a one-day delay.

US networks NBC and CBS made similar arrangements to have films flown in relays back to the United States for same-day broadcast, but used slower propeller-driven aircraft. NBC had originally planned to carry the event live via skywave

In radio communication, skywave or skip refers to the propagation of radio waves reflected or refracted back toward Earth from the ionosphere, an electrically charged layer of the upper atmosphere. Since it is not limited by the curvature of ...

direct from the BBC but was unable to establish a broadcast-quality video link on coronation day due to poor atmospheric conditions. The struggling ABC network arranged to re-transmit the CBC broadcast, taking the on-the-air signal from the CBC's Toronto station and feeding the network from WBEN-TV

WIVB-TV (channel 4) is a television station in Buffalo, New York, United States, affiliated with CBS. It is owned by Nexstar Media Group alongside CW owned-and-operated station WNLO (channel 23). WIVB-TV and WNLO share studios on Elmwood A ...

, Buffalo's lone television station at the time; as a result, ABC beat the other two networks to air by more than 90 minutes — and at considerably lower cost.

Although it did not as yet have a full-time television service, film was also dispatched to Australia aboard a Qantas airliner, which arrived in Sydney in a record time of 53 hours 28 minutes. The worldwide television audience for the coronation was estimated to be 277 million.

Procession

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the British Empire and Commonwealth, guests and officials passed in a procession before about three million spectators that were gathered on the streets of London, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built stands and scaffolding along the route. For those not present, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey, with 750 commentators broadcasting in 39 languages.

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to supplement the insufficient ranks of regular footmen. The first royal coach left

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the British Empire and Commonwealth, guests and officials passed in a procession before about three million spectators that were gathered on the streets of London, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built stands and scaffolding along the route. For those not present, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey, with 750 commentators broadcasting in 39 languages.

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to supplement the insufficient ranks of regular footmen. The first royal coach left Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

and moved down the Mall, which was filled with flag-waving and cheering crowds. It was followed by the Irish State Coach

The Irish State Coach is an enclosed, four-horse-drawn carriage used by the British Royal Family. It is the traditional horse-drawn coach in which the British monarch travels from Buckingham Palace to the Palace of Westminster to formally open ...

carrying Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was the l ...

, who wore the circlet of her crown bearing the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Queen Elizabeth II proceeded through London from Buckingham Palace, through Trafalgar Square, and towards the abbey in the Gold State Coach. Attached to the shoulders of her dress, the Queen wore the Robe of State, a long, hand woven silk velvet cloak lined with Canadian ermine that required the assistance of her maids of honour—Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill and the Duchess of Devonshire—to carry.

The return procession followed a route that was in length, passing along Whitehall, across Trafalgar Square, along Pall Mall and Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

to Hyde Park Corner, via Marble Arch and Oxford Circus

Oxford Circus is a road junction connecting Oxford Street and Regent Street in the West End of London. It is also the entrance to Oxford Circus tube station.

The junction opened in 1819 as part of the Regent Street development under John Nash, ...

, down Regent Street

Regent Street is a major shopping street in the West End of London. It is named after George, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and was laid out under the direction of the architect John Nash and James Burton. It runs from Waterloo Place ...

and Haymarket Haymarket may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Haymarket, New South Wales, area of Sydney, Australia

Germany

* Heumarkt (KVB), transport interchange in Cologne on the site of the Heumarkt (literally: hay market)

Russia

* Sennaya Square (''Hay Squ ...

, and finally along the Mall to Buckingham Palace. 29,000 service personnel from Britain and across the Commonwealth marched in a procession that was long and took 45 minutes to pass any given point. A further 15,800 lined the route. The parade was led by Colonel Burrows of the War Office staff and four regimental bands. Then came the colonial contingents, then troops from the Commonwealth realms, followed by the Royal Air Force, the British Army, the Royal Navy, and finally the Household Brigade

Household Division is a term used principally in the Commonwealth of Nations to describe a country's most elite or historically senior military units, or those military units that provide ceremonial or protective functions associated directly with ...

. Behind the marching troops was a carriage procession led by the rulers of the British protectorates, including Queen Sālote Tupou III

Sālote Tupou III (born Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu; 13 March 1900 – 16 December 1965) was Queen of Tonga from 1918 to her death in 1965. She reigned for nearly 48 years, longer than any other Tongan monarch. She was well known for her height ...

of Tonga, the Commonwealth prime ministers, the princes and princesses of the blood royal, and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. Preceded by the heads of the British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

on horseback, the Gold State Coach was escorted by the Yeomen of the Guard and the Household Cavalry and was followed by the Queen's aides-de-camp. So many carriages were required that some had to be borrowed from Elstree Studios.

After the end of the procession, the royal family appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to watch a flypast. The flypast had been altered on the day due to the bad weather, but otherwise took place as planned. 168 jet fighters flew overhead in three divisions thirty seconds apart, at an altitude of 1,500 feet.

Guests

Coronation Day Coronation Day is the anniversary of the coronation of a monarch, the day a king or queen is formally crowned and invested with the regalia.

By country

Cambodia

* Norodom Sihamoni - October 29, 2004

Ethiopia

* Haile Selassie I - November 2, 1930

...

to the approximately 8,000 guests invited from across the Commonwealth of Nations; more prominent individuals, such as members of the Queen's family and foreign royalty, the peers of the United Kingdom

The Peerage of the United Kingdom is one of the five Peerages in the United Kingdom. It comprises most peerages created in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801, when it replaced the ...

, heads of state, members of Parliament from the Queen's various legislatures, and the like, arrived after 8:30 a.m. Queen Sālote of Tonga was a guest, and was noted for her cheery demeanour while riding in an open carriage through London in the rain. General George Marshall, the former United States Secretary of State who implemented the Marshall Plan, was appointed chairman of the US delegation to the coronation and attended the ceremony along with his wife, Katherine.

Among other dignitaries who attended the event were Sir Winston Churchill, the prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohammad Ali Bogra and Col Anastasio Somoza Debayle

Anastasio "Tachito" Somoza Debayle (; 5 December 1925 – 17 September 1980) was the President of Nicaragua from 1 May 1967 to 1 May 1972 and from 1 December 1974 to 17 July 1979. As head of the National Guard, he was ''de facto'' ruler of ...

of Nicaragua.

Guests seated on stools were able to purchase their stools following the ceremony, with the profits going towards the cost of the coronation.

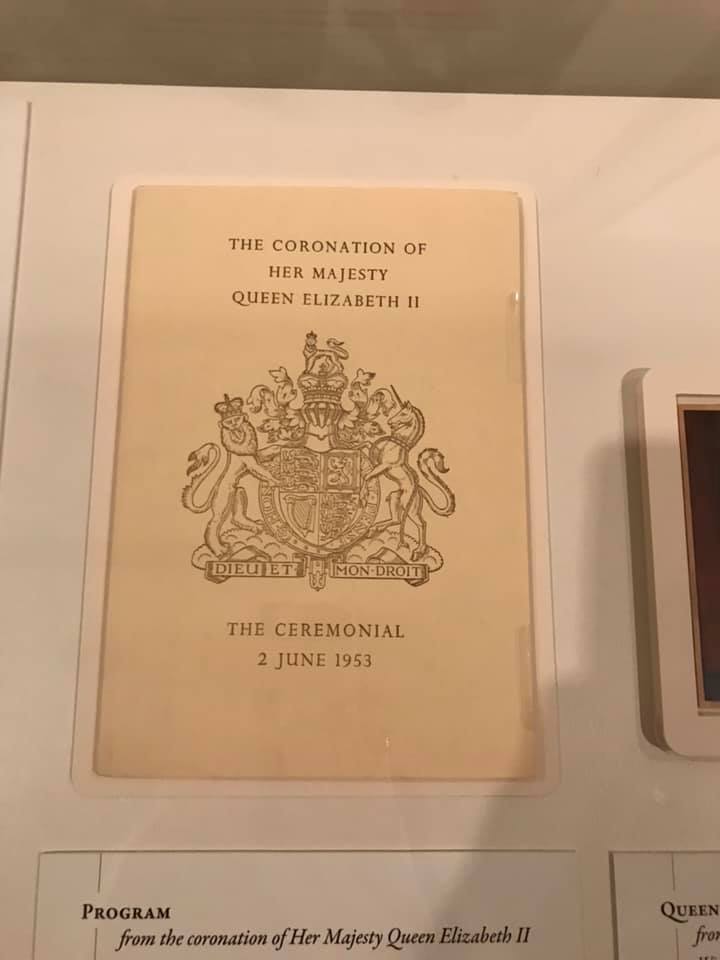

Ceremony

Preceding the Queen into Westminster Abbey was St Edward's Crown, carried into the abbey by the Lord High Steward of England, Lord Cunningham of Hyndhope, who was flanked by two other peers, while thearchbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

s and bishops assistant (Durham and Bath and Wells) of the Church of England, in their copes and mitres, waited outside the Great West Door for Queen Elizabeth II's arrival. When she arrived at about 11:00 am, she found that the friction between her robes and the carpet caused her difficulty moving forward, and she said to the archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, Geoffrey Fisher, "Get me started!" Once going, the procession, which included the various high commissioners

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift to ...

of the Commonwealth carrying banners bearing the shields of the coats of arms of their respective nations, moved inside the abbey, up the central aisle and through the choir to the stage, as the choirs sang " I was glad", an imperial setting of Psalm 122, vv. 1–3, 6, and 7 by Sir Hubert Parry. As Elizabeth prayed at and then seated herself on the Chair of Estate to the south of the altar, the bishops carried in the religious paraphernalia—the Bible, paten and chalice—and the peers holding the coronation regalia handed them over to the archbishop of Canterbury, who, in turn, passed them to the Dean of Westminster, Alan Campbell Don

Alan Campbell Don (3 January 1885 – 3 May 1966) was a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery, editor of the Scottish Episcopal Church's 1929 '' Scottish Prayer Book'', chaplain and secretary to Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury, from 1 ...

, to be placed on the altar.

After she moved to stand before King Edward's Chair, Elizabeth turned, following as Fisher, along with the

After she moved to stand before King Edward's Chair, Elizabeth turned, following as Fisher, along with the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

( Lord Simonds), Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable of England, Lord Hi ...

of England ( Lord Cholmondeley), Lord High Constable of England ( Lord Alanbrooke) and Earl Marshal of the United Kingdom (the Duke of Norfolk), all led by Garter Principal King of Arms

The Garter Principal King of Arms (also Garter King of Arms or simply Garter) is the senior King of Arms, and the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms, the heraldic authority with jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland. ...

George Bellew. The Archbishop of Canterbury asked the audience in each direction of the compass separately: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?" The crowd would reply "God save Queen Elizabeth!" every time, to each of which the Queen would curtsey in return.

Seated again on the Chair of Estate, Elizabeth then took the Coronation Oath as administered by the archbishop of Canterbury. In the lengthy oath, she swore to govern each of her countries according to their respective laws and customs, to mete out law and justice with mercy, to uphold Protestantism in the United Kingdom and protect the Church of England and preserve its bishops and clergy. She proceeded to the altar where she stated, "The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God", before kissing the Bible and putting the royal sign-manual to the oath as the Bible was returned to the dean of Westminster. From him the moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the ministers and elders of the Church of Scotland, minister or elder chosen to moderate (chair) the annual General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, which is held for a week i ...

, James Pitt-Watson, took the Bible and presented it to Elizabeth again, saying,

Elizabeth returned the book to Pitt-Watson, who placed it back with the dean of Westminster.

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter

The First Epistle of Peter is a book of the New Testament. The author presents himself as Peter the Apostle. The ending of the letter includes a statement that implies that it was written from "Babylon", which is possibly a reference to Rome. T ...

, Psalms, and the Gospel of Matthew. Elizabeth was then anointed as the choir sang " Zadok the Priest"; the Queen's jewellery and crimson cape were removed by Lord Ancaster and the Mistress of the Robes, the Duchess of Devonshire and, wearing only a simple, white linen dress also designed by Hartnell to completely cover the coronation gown, she moved to be seated in King Edward's Chair. There, Fisher, assisted by the dean of Westminster, made a cross on her forehead, hands and breast with holy oil made from the same base as had been used in the coronation of her father. At her request, the anointing ceremony was not televised.

From the altar, the dean passed to the lord great chamberlain the spurs, which were presented to Elizabeth and then placed back on the altar. The Sword of State was then handed to Elizabeth, who, after a prayer was uttered by Fisher, placed it herself on the altar, and the peer who had been previously holding it took it back again after paying a sum of 100 shillings. Elizabeth was then invested with the Armills (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal and the Sovereign's Orb, followed by the Queen's Ring, the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross

The Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, originally the Crown Jewels of England, are a collection of royal ceremonial objects kept in the Tower of London which include the coronation regalia and vestments worn by British monarchs.

Symbols of ov ...

and the Sovereign's Sceptre with Dove

The Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, originally the Crown Jewels of England, are a collection of royal ceremonial objects kept in the Tower of London which include the coronation regalia and vestments worn by British monarchs.

Symbols of ov ...

. With the first two items on and in her right hand and the latter in her left, Queen Elizabeth II was crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury, with the crowd chanting "God save the queen!" three times at the exact moment St Edward's Crown touched the monarch's head. The princes and peers gathered then put on their coronets and a 21-gun salute

A 21-gun salute is the most commonly recognized of the customary gun salutes that are performed by the firing of cannons or artillery as a military honor. As naval customs evolved, 21 guns came to be fired for heads of state, or in exceptiona ...

was fired from the Tower of London.

With the benediction read, Elizabeth moved to the throne and the archbishop of Canterbury and all the bishops offered to her their fealty, after which, while the choir sang, the peers of the United Kingdom—led by the royal peers: Elizabeth's husband; her uncle Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; and her cousin Prince Edward, Duke of Kent—each proceeded, in order of precedence, to pay their personal homage and allegiance. After the royal peers, the 5 most senior peers, one for each rank, offered their fealty as representatives of the peerage of the United Kingdom: Norfolk for dukes, Huntly for marquesses, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

for earls, Arbuthnott for viscounts and Mowbray for barons.

When the last baron had completed this task, the assembly shouted "God save Queen Elizabeth. Long live Queen Elizabeth. May the Queen live for ever!" Having removed all her royal regalia, Elizabeth knelt and took the communion, including a general confession and absolution, and, along with the congregation, recited the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

.

Now wearing the Imperial State Crown and holding the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb, and as the gathered guests sang " God Save the Queen", Elizabeth left Westminster Abbey through the nave and apse, out the Great West Door.

Music

Although many had assumed that the Master of the Queen's Music,

Although many had assumed that the Master of the Queen's Music, Sir Arnold Bax

Sir Arnold Edward Trevor Bax, (8 November 1883 – 3 October 1953) was an English composer, poet, and author. His prolific output includes songs, choral music, chamber pieces, and solo piano works, but he is best known for his orchestral musi ...

, would be the director of music for the coronation, it was decided instead to appoint the organist and master of the choristers at the abbey, William McKie, who had been in charge of music at the royal wedding in 1947. McKie convened an advisory committee with Sir Arnold Bax and Sir Ernest Bullock, who had directed the music for the previous coronation.

When it came to choosing the music, tradition required that Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

's '' Zadok the Priest'' and Parry's ''I was glad'' were included amongst the anthem

An anthem is a musical composition of celebration, usually used as a symbol for a distinct group, particularly the national anthems of countries. Originally, and in music theory and religious contexts, it also refers more particularly to short ...

s. Other choral works included were the anonymous 16th century anthem "Rejoice in the Lord alway" and Samuel Sebastian Wesley's ''Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace''. Another tradition was that new works be commissioned from the leading composers of the day: Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams, (; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

composed a new motet ''O Taste and See'', William Walton composed a setting for the Te Deum, and the Canadian composer Healey Willan

James Healey Willan (12 October 1880 – 16 February 1968) was an Anglo-Canadian organist and composer. He composed more than 800 works including operas, symphonies, chamber music, a concerto, and pieces for band, orchestra, organ, and pia ...

wrote an anthem ''O Lord our Governor''. Four new orchestral pieces were planned; Arthur Bliss composed ''Processional''; Walton, ''Orb and Sceptre

''Orb and Sceptre'' is a march for orchestra written by William Walton for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey, London, on 2 June 1953. It follows the pattern of earlier concert marches by Elgar and Walton himself in consi ...

''; and Arnold Bax, ''Coronation March''. Benjamin Britten had agreed to compose a piece, but he caught influenza and then had to deal with flooding at Aldeburgh, so nothing was forthcoming. Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

's ''Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in D'' was played immediately before Bax's march at the end of the ceremony. An innovation, at the suggestion of Vaughan Williams, was the inclusion of a hymn in which the congregation could participate. This proved controversial and was not included in the programme until Elizabeth had been consulted and found to be in favour; Vaughan Williams wrote an elaborate arrangement of the traditional metrical psalm

A metrical psalter is a kind of Bible translation: a book containing a verse translation of all or part of the Book of Psalms in vernacular poetry, meant to be sung as hymns in a church. Some metrical psalters include melodies or harmonisati ...

, the ''Old Hundredth'', which included military trumpet fanfares and was sung before the communion. Gordon Jacob wrote a choral arrangement of ''God Save the Queen'', also with trumpet fanfares.

The choir for the coronation was a combination of the choirs of Westminster Abbey, St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

, the Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also applie ...

, and Saint George's Chapel, Windsor. In addition to those established choirs, the Royal School of Church Music conducted auditions to find twenty boy trebles from parish church choirs representing the various regions of the United Kingdom. Along with twelve trebles chosen from various British cathedral choirs, the selected boys spent the month beforehand training at Addington Palace

Addington Palace is an 18th-century mansion in Addington located within the London Borough of Croydon. It was built on the site of a 16th-century manor house. It is particularly known for having been, between 1807 and 1897, the summer reside ...

. The final complement of choristers comprised 182 boy trebles, 37 male altos, 62 tenors and 67 basses. The orchestra, of 60 players, was drawn from the leading members of British symphony orchestras and chamber ensembles. Each of the 18 violinists, headed by Paul Beard, was the leader of a major orchestra or chamber group. The conductor was Sir Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

, who had conducted the orchestra at the previous coronation.

Celebrations, monuments and media

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra bank holiday

A bank holiday is a national public holiday in the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and the Crown Dependencies. The term refers to all public holidays in the United Kingdom, be they set out in statute, declared by royal proclamation or held ...

that fell on 3 June and moved the last bank holiday in May to 2 June to allow for an extended time of celebrations. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (french: link=no, Médaille du couronnement de la Reine Élizabeth II) is a commemorative medal instituted to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953.

Award

This medal was awarded a ...

was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the Royal Canadian Mint and distributed to schoolchildren across the country; the obverse showed Elizabeth's effigy and the reverse the royal cypher above the word ''CANADA'', all circumscribed by ''ELIZABETH II REGINA CORONATA MCMLIII''.

As at the coronation of George VI, acorns shed from oaks in Windsor Great Park, near Windsor Castle, were shipped around the Commonwealth and planted in parks, school grounds, cemeteries and private gardens to grow into what are known as ''Royal Oaks'' or ''Coronation Oaks''.

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup football tournament was held at

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park

Hampden Park (Scottish Gaelic: ''Pàirc Hampden''), often referred to as Hampden, is a football stadium in the Mount Florida area of Glasgow, Scotland. The -capacity venue serves as the national stadium of football in Scotland. It is the no ...

, Glasgow in May, and two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine ''Collins Magazine'' rebranded itself as ''The Young Elizabethan

''The Young Elizabethan'' was a British children's literary magazine of the 20th century.

History and profile

The magazine was founded in 1948 as ''Collins Magazine for Boys & Girls''. It was first published in Canada due to limitations of pape ...

''. News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen". In the following month, a pageant took place over the River Thames as a coronation tribute to the Queen.

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower. Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall. In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by Royal Canadian Air Force drops, and in Quebec, 400,000 people turned out in Montreal, some 100,000 at Jeanne-Mance Park alone. A multicultural show was put on at Exhibition Place in Toronto, square dances and exhibitions took place in the Prairie provinces and in Vancouver the Chinese community

The Chinese people or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by speakers of s ...

performed a public lion dance. On the Korean Peninsula, Canadian soldiers serving in the Korean War acknowledged the day by firing red, white, and blue coloured smoke shells at the enemy and drank rum rations.

Later events

Coronation Review of the Fleet

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. Commanded by Admiral Sir George Creasy were 197 Royal Navy warships, together with 13 from the Commonwealth and 16 from foreign navies, as well as representative vessels from the British Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. There were more British and Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. Commanded by Admiral Sir George Creasy were 197 Royal Navy warships, together with 13 from the Commonwealth and 16 from foreign navies, as well as representative vessels from the British Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. There were more British and Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s or smaller vessels. Major Royal Navy units included Britain's last battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, , and four fleet and three light aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s. The Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy also each included a light carrier in their contingents, and .

Using the frigate as a royal yacht

A royal yacht is a ship used by a monarch or a royal family. If the monarch is an emperor the proper term is imperial yacht. Most of them are financed by the government of the country of which the monarch is head. The royal yacht is most often c ...

, the Queen and royal family started to review the lines of anchored ships at 3:30 p.m., finally anchoring at 5:10 p.m. This was followed by a fly-past of Fleet Air Arm aircraft. Forty naval air squadrons participated, with 327 aircraft flying from four naval air stations; the formation was led by Rear Admiral Walter Couchman flying a de Havilland Sea Vampire. After the Queen transferred to ''Vanguard'' for dinner, the day concluded with the Illumination of the fleet and a fireworks display.

Honours of Scotland

During a week-long visit to Scotland, on 24 June 1953, the Queen attended a

During a week-long visit to Scotland, on 24 June 1953, the Queen attended a national service of thanksgiving

A national service of thanksgiving in the United Kingdom is an act of Christian worship, generally attended by the British monarch, Great Officers of State and Ministers of the Crown, which celebrates an event of national importance, originally to ...

at St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, during which she was ceremonially presented with the Honours of Scotland

The Honours of Scotland (, gd, Seudan a' Chrùin Albannaich), informally known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, are the regalia that were worn by Scottish monarchs at their coronation. Kept in the Crown Room in Edinburgh Castle, they date from the ...

, the Scottish crown jewels. Following a carriage procession through the city escorted by the Royal Company of Archers, the service, led by the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the ministers and elders of the Church of Scotland, minister or elder chosen to moderate (chair) the annual General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, which is held for a week i ...

, James Pitt-Watson

James Pitt-Watson (9 November 1893 – 25 December 1962) was a Scottish minister and academic. He was Professor of Practical Theology at Glasgow University and served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1953. He has b ...

, was attended by a congregation of 1,700 drawn from all sections of Scottish society. The high point of the event was the presentation of the Honours, which the queen received from the Dean of the Thistle

The Dean of the Thistle is an office of the Order of the Thistle, re-established in 1687. The office is normally held by a minister of the Church of Scotland, and forms part of the Royal Household in Scotland.

In 1886 the office of Dean of ...

, Charles Warr

Charles Laing Warr KCVO FRSE (1892–1969) was a Church of Scotland minister and author in the 20th century.

Life

Warr was born on 20 May 1892, the second son of the Reverend Alfred Warr, sometime minister of Rosneath in Dunbartonshire, a ...

, and then passed the Crown of Scotland to the Duke of Hamilton

Duke of Hamilton is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in April 1643. It is the senior dukedom in that peerage (except for the Dukedom of Rothesay held by the Sovereign's eldest son), and as such its holder is the premier peer of Sco ...

, the Sword of State to the Alec Douglas-Home, Earl of Home, and the Sceptre to the David Lindsay, 28th Earl of Crawford, Earl of Crawford and Balcarres. It was the first time that this ceremony had been enacted since 1822 during the visit of King George IV.

The queen was dressed in "day clothes" complete with a handbag, rather than in ceremonial robes, which was taken as a slight to Scotland's dignity by the Scottish press. The decision not to dress formally was made by the Private Secretary to the Sovereign, Sir Alan Lascelles, and Sir Austin Strutt, a senior civil servant at the Home Office. In the official painting of the ceremony by Stanley Cursiter, the offending handbag was tactfully omitted.

Coronation Review of the RAF

On 15 July 1953, the Queen attended a review of the Royal Air Force at RAF Odiham in Hampshire. The first part of the review was a march past by contigents representing the various commands of the RAF, with RAF Bomber Command, Bomber Command leading. This was followed by four de Havilland Venoms of the Central Fighter Establishment making the Royal Cypher in skywriting. After lunch, the queen in an open car toured the lines of some 300 aircraft that were arranged in a static display. She returned to the central dias for the flypast of 640 British and Commonwealth aircraft, of which 440 were jet-powered. The flypast was led by a Bristol Sycamore helicopter which was towing a large Royal Air Force Ensign, RAF Ensign, while the final aircraft was a prototype Supermarine Swift flown by test pilot Mike Lithgow. Finally, the skywriting Venoms spelled out the word "vivat".See also

* List of participants in the coronation procession of Elizabeth II * 1953 Coronation Honours * The Queen's Beasts, heraldic statues placed outside Westminster Abbey representing Elizabeth's genealogy * Canadian Coronation ContingentNotes

References

Further reading

* Clancy, Laura"'Queen's Day – TV's Day': the British monarchy and the media industries"

''Contemporary British History'', vol. 33, no. 3 (2019), pp. 427–450. * Feingold, Ruth P. "Every little girl can grow up to be queen: the coronation and The Virgin in the Garden." ''Literature & History'' 22.2 (2013): 73–90. * * Örnebring, Henrik. "Revisiting the Coronation: a Critical Perspective on the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953." ''Nordicom Review'' 25, no. 1-

online

2004) * Shils, Edward, and Michael Young. "The meaning of the coronation." ''The Sociological Review'' 1.2 (1953): 63–81. * * Weight, Richard. ''Patriots: National Identity in Britain 1940–2000'' (Pan Macmillan, 2013) pp 211–56.

External links

Order of Service of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

''Elizabeth is Queen'' (1953)

50 facts about The Queen's Coronation

Royal page {{DEFAULTSORT:Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II Coronation of Elizabeth II, 1953 in British television 1953 in international relations 1953 in London 1953 in the United Kingdom Coronations of British monarchs, Elizabeth II June 1953 events in the United Kingdom Monarchy in Canada Westminster Abbey 1950s in the City of Westminster