Coronation of Elizabeth II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function." The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function." The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage and clergy. However, for the new queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage and clergy. However, for the new queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the

After being closed since the Queen's accession for coronation preparations, Westminster Abbey was opened at 6 am on

After being closed since the Queen's accession for coronation preparations, Westminster Abbey was opened at 6 am on

After she moved to stand before

After she moved to stand before  The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter, Psalms, and the

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter, Psalms, and the

Although many had assumed that the

Although many had assumed that the

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra bank holiday that fell on 3 June and moved the last bank holiday in May to 2 June to allow for an extended time of celebrations. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra bank holiday that fell on 3 June and moved the last bank holiday in May to 2 June to allow for an extended time of celebrations. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the  In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup (football), Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park, Glasgow in May, and two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine ''Collins Magazine'' rebranded itself as ''The Young Elizabethan''. News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition, reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen". In the following month, a pageant took place over the River Thames as a coronation tribute to the Queen.

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup (football), Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park, Glasgow in May, and two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine ''Collins Magazine'' rebranded itself as ''The Young Elizabethan''. News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition, reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen". In the following month, a pageant took place over the River Thames as a coronation tribute to the Queen.

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The Governor General of Canada, country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower. Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall. In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The Governor General of Canada, country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower. Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall. In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. Commanded by Admiral Sir George Creasy were 197 Royal Navy warships, together with 13 from the Commonwealth and 16 from foreign navies, as well as representative vessels from the British Merchant Navy (United Kingdom), Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. There were more British and Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were frigates or smaller vessels. Major Royal Navy units included Britain's last battleship, , and four fleet and three light aircraft carriers. The Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy also each included a light carrier in their contingents, and .

Using the frigate as a royal yacht, the Queen and royal family started to review the lines of anchored ships at 3:30 p.m., finally anchoring at 5:10 p.m. This was followed by a fly-past of Fleet Air Arm aircraft. Forty naval air squadrons participated, with 327 aircraft flying from four naval air stations; the formation was led by Rear Admiral Walter Couchman flying a De Havilland Vampire, de Havilland Sea Vampire. After the Queen transferred to ''Vanguard'' for dinner, the day concluded with the Illumination of the fleet and a fireworks display.

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. Commanded by Admiral Sir George Creasy were 197 Royal Navy warships, together with 13 from the Commonwealth and 16 from foreign navies, as well as representative vessels from the British Merchant Navy (United Kingdom), Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. There were more British and Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were frigates or smaller vessels. Major Royal Navy units included Britain's last battleship, , and four fleet and three light aircraft carriers. The Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy also each included a light carrier in their contingents, and .

Using the frigate as a royal yacht, the Queen and royal family started to review the lines of anchored ships at 3:30 p.m., finally anchoring at 5:10 p.m. This was followed by a fly-past of Fleet Air Arm aircraft. Forty naval air squadrons participated, with 327 aircraft flying from four naval air stations; the formation was led by Rear Admiral Walter Couchman flying a De Havilland Vampire, de Havilland Sea Vampire. After the Queen transferred to ''Vanguard'' for dinner, the day concluded with the Illumination of the fleet and a fireworks display.

During a week-long visit to Scotland, on 24 June 1953, the Queen attended a national service of thanksgiving at St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, during which she was ceremonially presented with the Honours of Scotland, the Scottish crown jewels. Following a carriage procession through the city escorted by the Royal Company of Archers, the service, led by the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, James Pitt-Watson, was attended by a congregation of 1,700 drawn from all sections of Scottish society. The high point of the event was the presentation of the Honours, which the queen received from the Dean of the Thistle, Charles Warr, and then passed the Crown of Scotland to the Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton, Duke of Hamilton, the Sword of State to the Alec Douglas-Home, Earl of Home, and the Sceptre to the David Lindsay, 28th Earl of Crawford, Earl of Crawford and Balcarres. It was the first time that this ceremony had been enacted since 1822 during the visit of King George IV.

The queen was dressed in "day clothes" complete with a handbag, rather than in ceremonial robes, which was taken as a slight to Scotland's dignity by the Scottish press. The decision not to dress formally was made by the Private Secretary to the Sovereign, Sir Alan Lascelles, and Sir Austin Strutt, a senior civil servant at the Home Office. In the official painting of the ceremony by Stanley Cursiter, the offending handbag was tactfully omitted.

During a week-long visit to Scotland, on 24 June 1953, the Queen attended a national service of thanksgiving at St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, during which she was ceremonially presented with the Honours of Scotland, the Scottish crown jewels. Following a carriage procession through the city escorted by the Royal Company of Archers, the service, led by the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, James Pitt-Watson, was attended by a congregation of 1,700 drawn from all sections of Scottish society. The high point of the event was the presentation of the Honours, which the queen received from the Dean of the Thistle, Charles Warr, and then passed the Crown of Scotland to the Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton, Duke of Hamilton, the Sword of State to the Alec Douglas-Home, Earl of Home, and the Sceptre to the David Lindsay, 28th Earl of Crawford, Earl of Crawford and Balcarres. It was the first time that this ceremony had been enacted since 1822 during the visit of King George IV.

The queen was dressed in "day clothes" complete with a handbag, rather than in ceremonial robes, which was taken as a slight to Scotland's dignity by the Scottish press. The decision not to dress formally was made by the Private Secretary to the Sovereign, Sir Alan Lascelles, and Sir Austin Strutt, a senior civil servant at the Home Office. In the official painting of the ceremony by Stanley Cursiter, the offending handbag was tactfully omitted.

"'Queen's Day – TV's Day': the British monarchy and the media industries"

''Contemporary British History'', vol. 33, no. 3 (2019), pp. 427–450. * Feingold, Ruth P. "Every little girl can grow up to be queen: the coronation and The Virgin in the Garden." ''Literature & History'' 22.2 (2013): 73–90. * * Örnebring, Henrik. "Revisiting the Coronation: a Critical Perspective on the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953." ''Nordicom Review'' 25, no. 1-

online

2004) * Shils, Edward, and Michael Young. "The meaning of the coronation." ''The Sociological Review'' 1.2 (1953): 63–81. * * Weight, Richard. ''Patriots: National Identity in Britain 1940–2000'' (Pan Macmillan, 2013) pp 211–56.

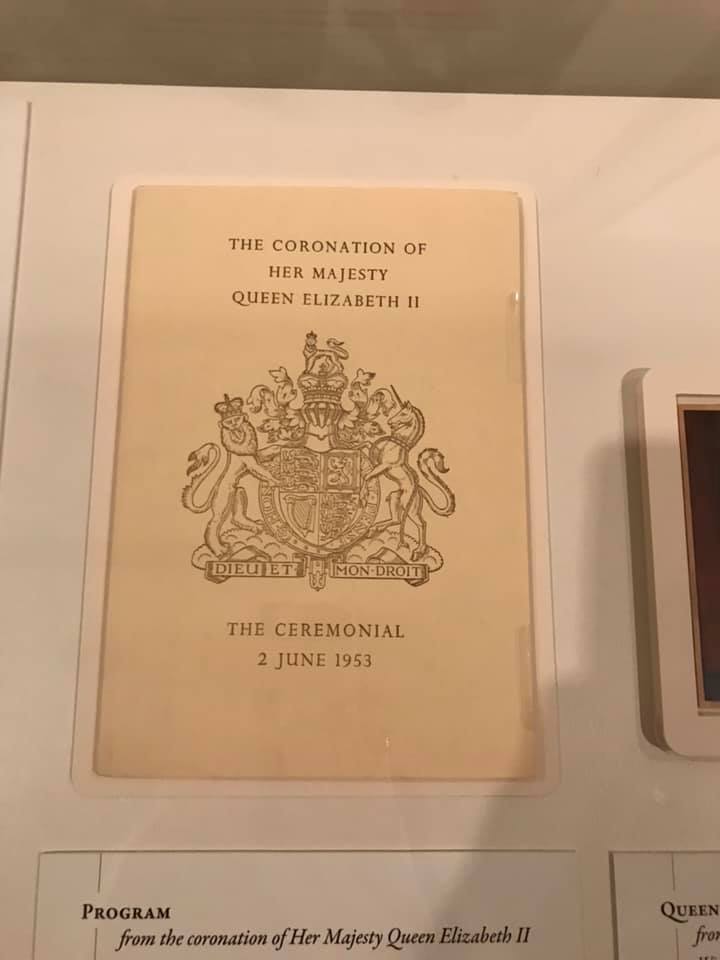

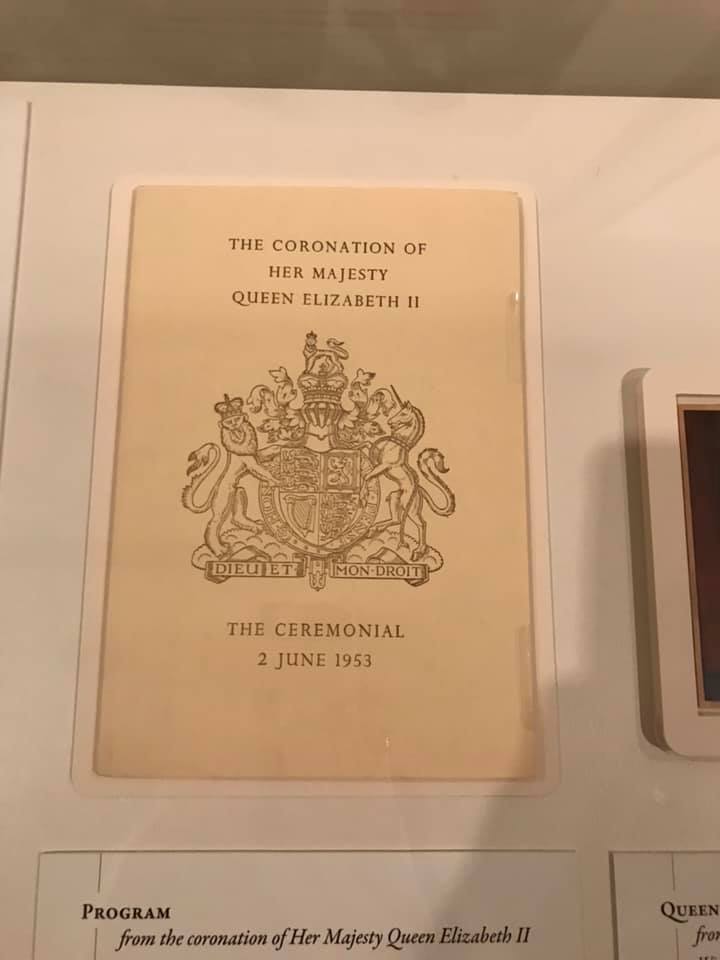

Order of Service of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

Videos of the celebrations''Canada at the Coronation'' (1953)''Coronation model aids architects'' (1952)

''Elizabeth is Queen'' (1953)

50 facts about The Queen's Coronation

Royal page {{DEFAULTSORT:Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II Coronation of Elizabeth II, 1953 in British television 1953 in international relations 1953 in London 1953 in the United Kingdom Coronations of British monarchs, Elizabeth II June 1953 events in the United Kingdom Monarchy in Canada Westminster Abbey 1950s in the City of Westminster

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. She acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon the death of her father, George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

, on 6 February 1952, being proclaimed queen by her privy and executive councils shortly afterwards. The coronation was held more than one year later because of the tradition of allowing an appropriate length of time to pass after a monarch dies before holding such festivals. It also gave the planning committees adequate time to make preparations for the ceremony. During the service, Elizabeth took an oath

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to g ...

, was anointed

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or oth ...

with holy oil, was invested with robes and regalia

Regalia is a Latin plurale tantum word that has different definitions. In one rare definition, it refers to the exclusive privileges of a sovereign. The word originally referred to the elaborate formal dress and dress accessories of a sovereig ...

, and was crowned Queen of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Celebrations took place across the Commonwealth realms and a commemorative medal

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

was issued. It has been the only British coronation to be fully televised; television cameras had not been allowed inside the abbey during her parents' coronation in 1937. Elizabeth's was the fourth and last British coronation of the 20th century. It was estimated to have cost £1.57 million (c. £43,427,400 in 2019).

Preparations

The one-day ceremony took 14 months of preparation: the first meeting of the Coronation Commission was in April 1952, under the chairmanship of the Queen's husband,Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from E ...

. Other committees were also formed, such as the Coronation Joint Committee and the Coronation Executive Committee, both chaired by the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

who, by convention as Earl Marshal

Earl marshal (alternatively marschal or marischal) is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England (then, following the Act of Union 1800, in the U ...

, had overall responsibility for the event. Many physical preparations and decorations along the route were the responsibility of David Eccles, Minister of Works. Eccles described his role and that of the Earl Marshal: "The Earl Marshal is the producer – I am the stage manager..."

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function." The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function." The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.

Norman Hartnell

Sir Norman Bishop Hartnell, KCVO (12 June 1901 – 8 June 1979) was a leading British fashion designer, best known for his work for the ladies of the royal family. Hartnell gained the Royal Warrant as Dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth in 1940, and ...

was commissioned by the Queen to design the outfits for all members of the royal family, including Elizabeth's coronation gown. His design for the gown evolved through nine proposals, and the final version resulted from his own research and numerous meetings with the Queen: a white silk dress embroidered with floral emblems of the countries of the Commonwealth at the time: the Tudor rose

The Tudor rose (sometimes called the Union rose) is the traditional floral heraldic emblem of England and takes its name and origins from the House of Tudor, which united the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The Tudor rose consists o ...

of England, Scottish thistle

Thistle is the common name of a group of flowering plants characterised by leaves with sharp prickles on the margins, mostly in the family Asteraceae. Prickles can also occur all over the planton the stem and on the flat parts of the leaves ...

, Welsh leek, shamrock for Northern Ireland, wattle of Australia, maple leaf

The maple leaf is the characteristic leaf of the maple tree. It is the most widely recognized national symbol of Canada.

History of use in Canada

By the early 1700s, the maple leaf had been adopted as an emblem by the French Canadians along th ...

of Canada, the New Zealand silver fern

''Alsophila dealbata'', synonym ''Cyathea dealbata'', commonly known as the silver fern or silver tree-fern, or as ponga or punga (from Māori or ),The Māori word , pronounced , has been borrowed into New Zealand English as a generic term fo ...

, South Africa's protea

''Protea'' () is a genus of South African flowering plants, also called sugarbushes (Afrikaans: ''suikerbos'').

Etymology

The genus ''Protea'' was named in 1735 by Carl Linnaeus, possibly after the Greek god Proteus, who could change his form a ...

, two lotus flowers

''Nelumbo nucifera'', also known as sacred lotus, Laxmi lotus, Indian lotus, or simply lotus, is one of two extant species of aquatic plant in the family Nelumbonaceae. It is sometimes colloquially called a water lily, though this more often re ...

for India and Ceylon, and Pakistan's wheat, cotton and jute. Roger Vivier

Roger Henri Vivier (13 November 1907 – 2 October 1998) was a French fashion designer who specialized in shoes. His best-known creation was the stiletto heel.

Career

Vivier has been called the " Fragonard of the shoe" and his shoes "the ...

created a pair of gold pumps for the occasion. The shoe featured jewel-encrusted heels and decorative motif on the upper sides, which was meant to resemble "the fleurs-de-lis pattern on the St Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th cen ...

and the Imperial State Crown

The Imperial State Crown is one of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom and symbolises the sovereignty of the monarch.

It has existed in various forms since the 15th century. The current version was made in 1937 and is worn by the monarc ...

". Elizabeth chose to wear the Coronation necklace for the event. The piece was commissioned by Queen Victoria and worn by Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 t ...

, Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth at their respective coronations. She paired it with the Coronation earrings.

Elizabeth rehearsed for the occasion with her maids of honour. A sheet was used in place of the velvet train, and a formation of chairs stood in for the carriage. She also wore the Imperial State Crown while going about her daily business – at her desk, during tea, and while reading a newspaper – so that she could become accustomed to its feel and weight. Elizabeth took part in two full rehearsals at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

, on 22 and 29 May, though some sources claim that she attended one or "several" rehearsals. The Duchess of Norfolk

Duchess of Norfolk is a title held by the wife of the Duke of Norfolk in the Peerage of England. The Duke of Norfolk is the premier duke in the peerage of England, and also, as Earl of Arundel, the premier earl. The first creation was in 1397.

Du ...

usually stood in for the Queen at rehearsals.

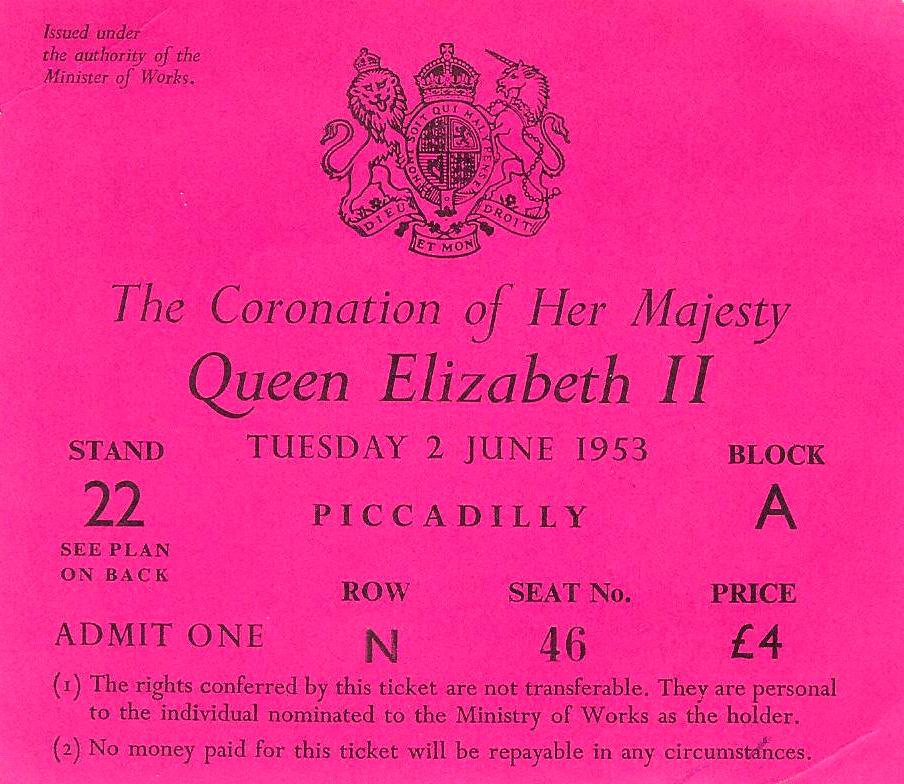

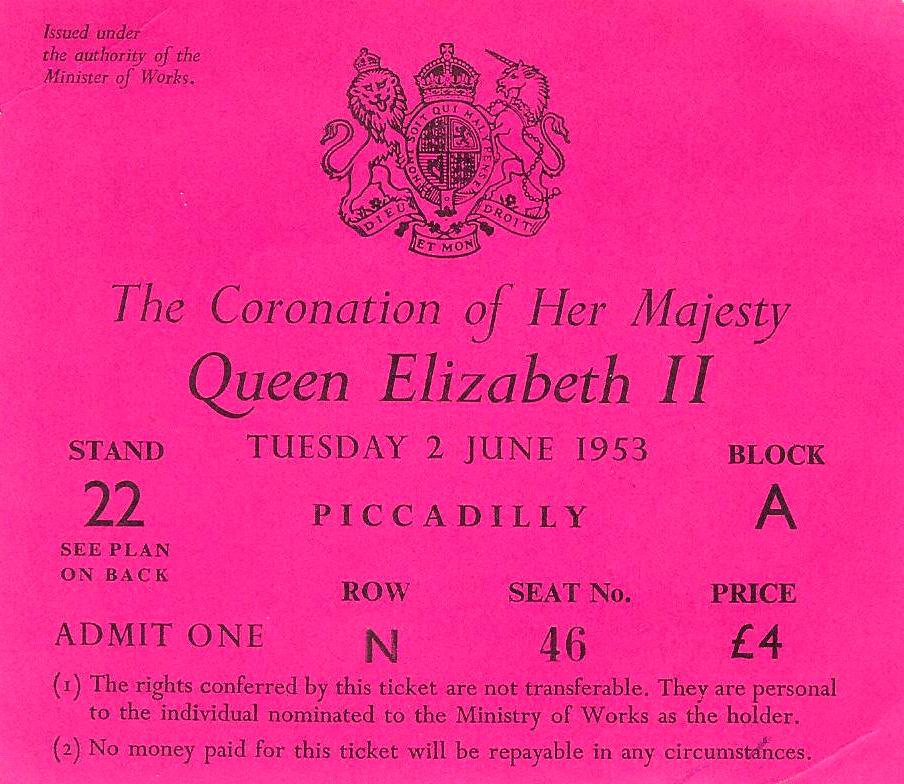

Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary had died on 24 March 1953, having stated in her will that her death should not affect the planning of the coronation, and the event went ahead as scheduled. It was estimated to cost £1.57 million (c£. in ), which included stands along the procession route to accommodate 96,000 people, lavatories, street decorations, outfits, car hire, repairs to the state coach, and alterations to the Queen's regalia.

Event

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage and clergy. However, for the new queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

The coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a pattern similar to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage and clergy. However, for the new queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

Television

Millions across Britain watched the coronation live on the BBC Television Service, and many purchased or rented television sets for the event. The coronation was the first to be televised in full; the BBC's cameras had not been allowed inside Westminster Abbey for her parents' coronation in 1937, and had covered only the procession outside. There had been considerable debate within theBritish Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the senior decision-making body of His Majesty's Government. A committee of the Privy Council, it is chaired by the prime minister and its members include secretaries of state and other senior ministers. ...

on the subject, with Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

against the idea; Elizabeth refused his advice on this matter and insisted the event take place before television cameras, as well as those filming with experimental 3D technology. The event was also filmed in colour, separately from the BBC's black and white television broadcast, where an average of 17 people watched each small TV.

Elizabeth's coronation was also the first major world event to be broadcast internationally on television.

In Europe, thanks to new relay links, this was the first live broadcast of an event taking place in the United Kingdom. The coronation was broadcast in France, Belgium, West Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, marking the birth of Eurovision.

To make sure Canadians could see it on the same day, RAF Canberras flew BBC film recordings of the ceremony across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to be broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the government. ...

(CBC), the first non-stop flights between the United Kingdom and the Canadian mainland. At Goose Bay, Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

, the first batch of film was transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

(RCAF) CF-100

The Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck (affectionately known as the "Clunk") is a Canadian twinjet Interceptor aircraft, interceptor/fighter aircraft, fighter designed and produced by aircraft manufacturer Avro Canada. It has the distinction of being t ...

jet fighter for the further trip to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

. In all, three such flights were made as the coronation proceeded, with the first and second Canberras taking the second and third batches of film, respectively, to Montreal. The following day, a film was flown west to Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

, whose CBC Television affiliate had yet to sign on. The film was escorted by the RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

to the Peace Arch Border Crossing, where it was then escorted by the Washington State Patrol

The Washington State Patrol (WSP) is the state patrol agency for the U.S. state of Washington. Organized as the Washington State Highway Patrol in 1921, it was renamed and reconstituted in 1933. The agency is charged with the protection of the G ...

to Bellingham, where it was shown as the inaugural broadcast of KVOS-TV

KVOS-TV, virtual channel 12 (UHF digital channel 14), is a Heroes & Icons owned-and-operated television station licensed to Bellingham, Washington, United States. Owned by Chicago-based Weigel Broadcasting, it is part of a duopoly with Seattl ...

, a new station whose signal reached into the Lower Mainland of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, allowing viewers there to see the coronation as well, though on a one-day delay.

US networks NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

and CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

made similar arrangements to have films flown in relays back to the United States for same-day broadcast, but used slower propeller-driven aircraft. NBC had originally planned to carry the event live via skywave direct from the BBC but was unable to establish a broadcast-quality video link on coronation day due to poor atmospheric conditions. The struggling ABC

ABC are the first three letters of the Latin script known as the alphabet.

ABC or abc may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Broadcasting

* American Broadcasting Company, a commercial U.S. TV broadcaster

** Disney–ABC Television ...

network arranged to re-transmit the CBC broadcast, taking the on-the-air signal from the CBC's Toronto station and feeding the network from WBEN-TV, Buffalo's lone television station at the time; as a result, ABC beat the other two networks to air by more than 90 minutes — and at considerably lower cost.

Although it did not as yet have a full-time television service, film was also dispatched to Australia aboard a Qantas

Qantas Airways Limited ( ) is the flag carrier of Australia and the country's largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations. It is the world's third-oldest airline still in operation, having been founde ...

airliner, which arrived in Sydney in a record time of 53 hours 28 minutes. The worldwide television audience for the coronation was estimated to be 277 million.

Procession

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and Commonwealth, guests and officials passed in a procession before about three million spectators that were gathered on the streets of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built stands and scaffolding along the route. For those not present, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

, with 750 commentators broadcasting in 39 languages.

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to supplement the insufficient ranks of regular footmen. The first royal coach left Buckingham Palace and moved down the Mall, which was filled with flag-waving and cheering crowds. It was followed by the Irish State Coach carrying Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, who wore the circlet of her crown bearing the Koh-i-Noor

The Koh-i-Noor ( ; from ), also spelled Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur, is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing . It is part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. The diamond is currently set in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth The ...

diamond. Queen Elizabeth II proceeded through London from Buckingham Palace, through Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, and towards the abbey in the Gold State Coach

The Gold State Coach is an enclosed, eight-horse-drawn carriage used by the British Royal Family. Commissioned in 1760 by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings for King George III, it was built in the London workshops of Samuel Bu ...

. Attached to the shoulders of her dress, the Queen wore the Robe of State, a long, hand woven silk velvet

Weave details visible on a purple-colored velvet fabric

Velvet is a type of woven tufted fabric in which the cut threads are evenly distributed, with a short pile, giving it a distinctive soft feel. By extension, the word ''velvety'' means ...

cloak lined with Canadian ermine that required the assistance of her maids of honour

A maid of honour is a junior attendant of a queen in royal households. The position was and is junior to the lady-in-waiting. The equivalent title and office has historically been used in most European royal courts.

Role

Traditionally, a queen ...

—Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill

Lady Rosemary Mildred Muir (née Spencer-Churchill; born 24 July 1929) is an English aristocrat who served as a maid of honour to Elizabeth II at her coronation in 1953.

Early life and family

Lady Rosemary Mildred Spencer-Churchill was born ...

and the Duchess of Devonshire—to carry.

The return procession followed a route that was in length, passing along Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

, across Trafalgar Square, along Pall Mall and Piccadilly to Hyde Park Corner

Hyde Park Corner is between Knightsbridge, Belgravia and Mayfair in London, England. It primarily refers to its major road junction at the southeastern corner of Hyde Park, that was designed by Decimus Burton. Six streets converge at the j ...

, via Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near the site of what is toda ...

and Oxford Circus, down Regent Street and Haymarket Haymarket may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Haymarket, New South Wales, area of Sydney, Australia

Germany

* Heumarkt (KVB), transport interchange in Cologne on the site of the Heumarkt (literally: hay market)

Russia

* Sennaya Square (''Hay Squ ...

, and finally along the Mall to Buckingham Palace. 29,000 service personnel from Britain and across the Commonwealth marched in a procession that was long and took 45 minutes to pass any given point. A further 15,800 lined the route. The parade was led by Colonel Burrows of the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

staff and four regimental bands. Then came the colonial contingents, then troops from the Commonwealth realms, followed by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

, the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, and finally the Household Brigade

Household Division is a term used principally in the Commonwealth of Nations to describe a country's most elite or historically senior military units, or those military units that provide ceremonial or protective functions associated directly with ...

. Behind the marching troops was a carriage procession led by the rulers of the British protectorates, including Queen Sālote Tupou III

Sālote Tupou III (born Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu; 13 March 1900 – 16 December 1965) was Queen of Tonga from 1918 to her death in 1965. She reigned for nearly 48 years, longer than any other Tongan monarch. She was well known for her height ...

of Tonga, the Commonwealth prime ministers, the princes and princesses of the blood royal, and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. Preceded by the heads of the British Armed Forces on horseback, the Gold State Coach was escorted by the Yeomen of the Guard

The King's Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard is a bodyguard of the British monarch. The oldest British military corps still in existence, it was created by King Henry VII in 1485 after the Battle of Bosworth Field.

History

The king ...

and the Household Cavalry

The Household Cavalry (HCav) is made up of the two most senior regiments of the British Army, the Life Guards and the Blues and Royals (Royal Horse Guards and 1st Dragoons). These regiments are divided between the Household Cavalry Regiment sta ...

and was followed by the Queen's aides-de-camp. So many carriages were required that some had to be borrowed from Elstree Studios

Elstree Studios is a generic term which can refer to several current and demolished British film studios and television studios based in or around the town of Borehamwood and village of Elstree in Hertfordshire, England. Production studios ha ...

.

After the end of the procession, the royal family appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to watch a flypast

A flypast is a ceremonial or honorific flight by an aircraft or group of aircraft. The term flypast is used in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. In the United States, the terms flyover and flyby are used.

Flypasts are often tied in wi ...

. The flypast had been altered on the day due to the bad weather, but otherwise took place as planned. 168 jet fighters flew overhead in three divisions thirty seconds apart, at an altitude of 1,500 feet.

Guests

Coronation Day Coronation Day is the anniversary of the coronation of a monarch, the day a king or queen is formally crowned and invested with the regalia.

By country

Cambodia

* Norodom Sihamoni - October 29, 2004

Ethiopia

* Haile Selassie I - November 2, 1930

...

to the approximately 8,000 guests invited from across the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

; more prominent individuals, such as members of the Queen's family and foreign royalty, the peers of the United Kingdom, heads of state, members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

from the Queen's various legislatures, and the like, arrived after 8:30 a.m. Queen Sālote of Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

was a guest, and was noted for her cheery demeanour while riding in an open carriage through London in the rain. General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

, the former United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

who implemented the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

, was appointed chairman of the US delegation to the coronation and attended the ceremony along with his wife, Katherine.

Among other dignitaries who attended the event were Sir Winston Churchill, the prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and Mohammad Ali Bogra

Sahibzada Syed Mohammad Ali Chowdhury ( bn, সৈয়দ মোহাম্মদ আলী চৌধুরী; Urdu: سید محمد علی چوہدری), more commonly known as Mohammad Ali Bogra ( bn, মোহাম্মদ আলী ...

and Col Anastasio Somoza Debayle of Nicaragua.

Guests seated on stools were able to purchase their stools following the ceremony, with the profits going towards the cost of the coronation.

Ceremony

Preceding the Queen into Westminster Abbey wasSt Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th cen ...

, carried into the abbey by the Lord High Steward

The Lord High Steward is the first of the Great Officers of State in England, nominally ranking above the Lord Chancellor.

The office has generally remained vacant since 1421, and is now an ''ad hoc'' office that is primarily ceremonial and ...

of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Lord Cunningham of Hyndhope, who was flanked by two other peers, while the archbishops and bishops assistant (Durham and Bath and Wells) of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, in their cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colour.

A c ...

s and mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

s, waited outside the Great West Door for Queen Elizabeth II's arrival. When she arrived at about 11:00 am, she found that the friction between her robes and the carpet caused her difficulty moving forward, and she said to the archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Francis Fisher, Baron Fisher of Lambeth, (5 May 1887 – 15 September 1972) was an English Anglican priest, and 99th Archbishop of Canterbury, serving from 1945 to 1961.

From a long line of parish priests, Fisher was educated at Marlb ...

, "Get me started!" Once going, the procession, which included the various high commissioners of the Commonwealth carrying banners bearing the shields of the coats of arms of their respective nations, moved inside the abbey, up the central aisle and through the choir to the stage, as the choirs sang "I was glad

"I was glad" (Latin incipit, "Laetatus sum") is a choral introit which is a popular piece in the musical repertoire of the Anglican church. It is traditionally sung in the Church of England as an anthem at the Coronation of the British monarch.

...

", an imperial setting of Psalm 122

Psalm 122 is the 122nd psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "I was glad" and in Latin entitled Laetatus sum. It is attributed to King David and one of the fifteen psalms described as A song of ascents (Sh ...

, vv. 1–3, 6, and 7 by Sir Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill, Bournemouth, Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 18 ...

. As Elizabeth prayed at and then seated herself on the Chair of Estate to the south of the altar, the bishops carried in the religious paraphernalia—the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

, paten

A paten or diskos is a small plate, used during the Mass. It is generally used during the liturgy itself, while the reserved sacrament are stored in the tabernacle in a ciborium.

Western usage

In many Western liturgical denominations, the p ...

and chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

R ...

—and the peers holding the coronation regalia handed them over to the archbishop of Canterbury, who, in turn, passed them to the Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the Abbey's status as a Royal Peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterbu ...

, Alan Campbell Don, to be placed on the altar.

After she moved to stand before

After she moved to stand before King Edward's Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

, Elizabeth turned, following as Fisher, along with the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

(Lord Simonds

Gavin Turnbull Simonds, 1st Viscount Simonds, (28 November 1881 – 28 June 1971) was a British judge, politician and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.

Background and education

Simonds was born in Reading, Berkshire, the son of Louis DeLuz ...

), Lord Great Chamberlain of England (Lord Cholmondeley

Marquess of Cholmondeley ( ) is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1815 for George Cholmondeley, 4th Earl of Cholmondeley.

History

The Cholmondeley family descends from William le Belward (or de Belward), the fe ...

), Lord High Constable of England

The Lord High Constable of England is the seventh of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Great Chamberlain and above the Earl Marshal. This office is now called out of abeyance only for coronations. The Lord High Constable was ...

( Lord Alanbrooke) and Earl Marshal

Earl marshal (alternatively marschal or marischal) is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England (then, following the Act of Union 1800, in the U ...

of the United Kingdom (the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

), all led by Garter Principal King of Arms George Bellew

Sir George Rothe Bellew, (13 December 1899 – 6 February 1993), styled The Honourable after 1935, was a long-serving herald at the College of Arms in London. Educated at the University of Oxford, he was appointed Portcullis Pursuivant in 1922. ...

. The Archbishop of Canterbury asked the audience in each direction of the compass separately: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?" The crowd would reply "God save Queen Elizabeth!" every time, to each of which the Queen would curtsey in return.

Seated again on the Chair of Estate, Elizabeth then took the Coronation Oath as administered by the archbishop of Canterbury. In the lengthy oath, she swore to govern each of her countries according to their respective laws and customs, to mete out law and justice with mercy, to uphold Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

in the United Kingdom and protect the Church of England and preserve its bishops and clergy. She proceeded to the altar where she stated, "The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God", before kissing the Bible and putting the royal sign-manual

The royal sign-manual is the signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive act (for example, an appointmen ...

to the oath as the Bible was returned to the dean of Westminster. From him the moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, James Pitt-Watson, took the Bible and presented it to Elizabeth again, saying,

Elizabeth returned the book to Pitt-Watson, who placed it back with the dean of Westminster.

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter, Psalms, and the

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter, Psalms, and the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and form ...

. Elizabeth was then anointed as the choir sang "Zadok the Priest

''Zadok the Priest'' ( HWV 258) is a British anthem that was composed by George Frideric Handel for the coronation of King George II in 1727. Alongside '' The King Shall Rejoice'', '' My Heart is Inditing'' and '' Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened' ...

"; the Queen's jewellery and crimson cape were removed by Lord Ancaster and the Mistress of the Robes

The mistress of the robes was the senior lady in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom.

Formerly responsible for the queen consort's/regnant's clothes and jewellery (as the name implies), the post had the responsibility for arranging the rota ...

, the Duchess of Devonshire and, wearing only a simple, white linen dress also designed by Hartnell to completely cover the coronation gown, she moved to be seated in King Edward's Chair. There, Fisher, assisted by the dean of Westminster, made a cross on her forehead, hands and breast with holy oil made from the same base as had been used in the coronation of her father. At her request, the anointing ceremony was not televised.

From the altar, the dean passed to the lord great chamberlain the spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

s, which were presented to Elizabeth and then placed back on the altar. The Sword of State was then handed to Elizabeth, who, after a prayer was uttered by Fisher, placed it herself on the altar, and the peer who had been previously holding it took it back again after paying a sum of 100 shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

. Elizabeth was then invested with the Armill

An armill or armilla (from the Latin: ''armillae'' remains the plural of armilla) is a type of medieval bracelet, or armlet, normally in metal and worn in pairs, one for each arm. They were usually worn as part of royal regalia, for example at a ...

s (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal and the Sovereign's Orb

The Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, originally the Crown Jewels of England, are a collection of royal ceremonial objects kept in the Tower of London which include the coronation regalia and vestments worn by British monarchs.

Symbols of ov ...

, followed by the Queen's Ring, the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross and the Sovereign's Sceptre with Dove. With the first two items on and in her right hand and the latter in her left, Queen Elizabeth II was crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury, with the crowd chanting "God save the queen!" three times at the exact moment St Edward's Crown touched the monarch's head. The princes and peers gathered then put on their coronets and a 21-gun salute

A 21-gun salute is the most commonly recognized of the customary gun salutes that are performed by the firing of cannons or artillery as a military honor. As naval customs evolved, 21 guns came to be fired for heads of state, or in exceptiona ...

was fired from the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

.

With the benediction read, Elizabeth moved to the throne and the archbishop of Canterbury and all the bishops offered to her their fealty, after which, while the choir sang, the peers of the United Kingdom—led by the royal peers: Elizabeth's husband; her uncle Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was the third son and fourth child of King George V and Queen Mary. He served as Governor-General of Australia from 1945 to 1947, the only memb ...

; and her cousin Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, (Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick; born 9 October 1935) is a member of the British royal family. Queen Elizabeth II and Edward were first cousins through their fathers, King George VI, and Prince George, Duke ...

—each proceeded, in order of precedence, to pay their personal homage and allegiance. After the royal peers, the 5 most senior peers, one for each rank, offered their fealty as representatives of the peerage of the United Kingdom: Norfolk for dukes, Huntly

Huntly ( gd, Srath Bhalgaidh or ''Hunndaidh'') is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, formerly known as Milton of Strathbogie or simply Strathbogie. It had a population of 4,460 in 2004 and is the site of Huntly Castle. Its neighbouring settlement ...

for marquesses, Shrewsbury for earls, Arbuthnott

Arbuthnott ( gd, Obar Bhuadhnait, "mouth of the Buadhnat") is a village and parish in the Howe of the Mearns, a low-lying agricultural district of Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is located on the B967, east of Fordoun (on the A90) and north-west ...

for viscounts and Mowbray for barons.

When the last baron had completed this task, the assembly shouted "God save Queen Elizabeth. Long live Queen Elizabeth. May the Queen live for ever!" Having removed all her royal regalia, Elizabeth knelt and took the communion, including a general confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

and absolution

Absolution is a traditional theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the pr ...

, and, along with the congregation, recited the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

.

Now wearing the Imperial State Crown and holding the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb, and as the gathered guests sang "God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" is the national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in plainchant, bu ...

", Elizabeth left Westminster Abbey through the nave and apse, out the Great West Door.

Music

Although many had assumed that the

Although many had assumed that the Master of the Queen's Music

Master of the King's Music (or Master of the Queen's Music, or earlier Master of the King's Musick) is a post in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. The holder of the post originally served the monarch of England, directing the court orche ...

, Sir Arnold Bax, would be the director of music for the coronation, it was decided instead to appoint the organist and master of the choristers at the abbey, William McKie, who had been in charge of music at the royal wedding

''Royal Wedding'' is a 1951 American musical comedy film directed by Stanley Donen, and starring Fred Astaire and Jane Powell, with music by Burton Lane and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner. Set in 1947 London at the time of the wedding of Princess ...

in 1947. McKie convened an advisory committee with Sir Arnold Bax and Sir Ernest Bullock, who had directed the music for the previous coronation.

When it came to choosing the music, tradition required that Handel's ''Zadok the Priest

''Zadok the Priest'' ( HWV 258) is a British anthem that was composed by George Frideric Handel for the coronation of King George II in 1727. Alongside '' The King Shall Rejoice'', '' My Heart is Inditing'' and '' Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened' ...

'' and Parry's ''I was glad'' were included amongst the anthems. Other choral works included were the anonymous 16th century anthem "Rejoice in the Lord alway" and Samuel Sebastian Wesley

Samuel Sebastian Wesley (14 August 1810 – 19 April 1876) was an English organist and composer. Wesley married Mary Anne Merewether and had 6 children. He is often referred to as S.S. Wesley to avoid confusion with his father Samuel Wesley.

Bio ...

's ''Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace''. Another tradition was that new works be commissioned from the leading composers of the day: Ralph Vaughan Williams composed a new motet ''O Taste and See'', William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

composed a setting for the Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Ch ...

, and the Canadian composer Healey Willan

James Healey Willan (12 October 1880 – 16 February 1968) was an Anglo-Canadian organist and composer. He composed more than 800 works including operas, symphonies, chamber music, a concerto, and pieces for band, orchestra, organ, and ...

wrote an anthem ''O Lord our Governor''. Four new orchestral pieces were planned; Arthur Bliss

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he qu ...

composed ''Processional''; Walton, '' Orb and Sceptre''; and Arnold Bax, ''Coronation March''. Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

had agreed to compose a piece, but he caught influenza and then had to deal with flooding at Aldeburgh, so nothing was forthcoming. Edward Elgar's ''Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in D'' was played immediately before Bax's march at the end of the ceremony. An innovation, at the suggestion of Vaughan Williams, was the inclusion of a hymn in which the congregation could participate. This proved controversial and was not included in the programme until Elizabeth had been consulted and found to be in favour; Vaughan Williams wrote an elaborate arrangement of the traditional metrical psalm

A metrical psalter is a kind of Bible translation: a book containing a verse translation of all or part of the Book of Psalms in vernacular poetry, meant to be sung as hymns in a church. Some metrical psalters include melodies or harmonisati ...

, the ''Old Hundredth'', which included military trumpet fanfares and was sung before the communion. Gordon Jacob

Gordon Percival Septimus Jacob CBE (5 July 18958 June 1984) was an English composer and teacher. He was a professor at the Royal College of Music in London from 1924 until his retirement in 1966, and published four books and many articles about ...

wrote a choral arrangement of ''God Save the Queen'', also with trumpet fanfares.

The choir for the coronation was a combination of the choirs of Westminster Abbey, St Paul's Cathedral, the Chapel Royal, and Saint George's Chapel, Windsor. In addition to those established choirs, the Royal School of Church Music

The Royal School of Church Music (RSCM) is a Christian music education organisation dedicated to the promotion of music in Christian worship, in particular the repertoire and traditions of Anglican church music, largely through publications, tr ...

conducted auditions to find twenty boy trebles from parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

choirs representing the various regions of the United Kingdom. Along with twelve trebles chosen from various British cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominatio ...

choirs, the selected boys spent the month beforehand training at Addington Palace

Addington Palace is an 18th-century mansion in Addington located within the London Borough of Croydon. It was built on the site of a 16th-century manor house. It is particularly known for having been, between 1807 and 1897, the summer resid ...

. The final complement of choristers comprised 182 boy trebles, 37 male altos, 62 tenors and 67 basses. The orchestra, of 60 players, was drawn from the leading members of British symphony orchestras and chamber ensembles. Each of the 18 violinists, headed by Paul Beard, was the leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

of a major orchestra or chamber group. The conductor was Sir Adrian Boult, who had conducted the orchestra at the previous coronation.

Celebrations, monuments and media

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra bank holiday that fell on 3 June and moved the last bank holiday in May to 2 June to allow for an extended time of celebrations. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The British government announced an extra bank holiday that fell on 3 June and moved the last bank holiday in May to 2 June to allow for an extended time of celebrations. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the Royal Canadian Mint

}) is the mint of Canada and a Crown corporation, operating under the ''Royal Canadian Mint Act''. The shares of the Mint are held in trust for the Crown in right of Canada.

The Mint produces all of Canada's circulation coins, and manufacture ...

and distributed to schoolchildren across the country; the obverse showed Elizabeth's effigy and the reverse the royal cypher above the word ''CANADA'', all circumscribed by ''ELIZABETH II REGINA CORONATA MCMLIII''.

As at the coronation of George VI, acorns shed from oaks in Windsor Great Park

Windsor Great Park is a Royal Park of , including a deer park, to the south of the town of Windsor on the border of Berkshire and Surrey in England. It is adjacent to the private Home Park, which is nearer the castle. The park was, for man ...

, near Windsor Castle, were shipped around the Commonwealth and planted in parks, school grounds, cemeteries and private gardens to grow into what are known as ''Royal Oaks'' or ''Coronation Oaks''.

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup (football), Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park, Glasgow in May, and two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine ''Collins Magazine'' rebranded itself as ''The Young Elizabethan''. News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition, reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen". In the following month, a pageant took place over the River Thames as a coronation tribute to the Queen.

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment. Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup (football), Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park, Glasgow in May, and two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine ''Collins Magazine'' rebranded itself as ''The Young Elizabethan''. News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition, reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen". In the following month, a pageant took place over the River Thames as a coronation tribute to the Queen.

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The Governor General of Canada, country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower. Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall. In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The Governor General of Canada, country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower. Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall. In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

drops, and in Quebec, 400,000 people turned out in Montreal, some 100,000 at Jeanne-Mance Park alone. A Multiculturalism, multicultural show was put on at Exhibition Place in Toronto, square dances and exhibitions took place in the Canadian Prairies, Prairie provinces and in Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

the Chinatown, Vancouver, Chinese community performed a public lion dance. On the Korea, Korean Peninsula, Canadian soldiers serving in the Korean War acknowledged the day by firing red, white, and blue coloured Shell (projectile)#Smoke, smoke shells at the enemy and drank rum rations.

Later events

Coronation Review of the Fleet

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. Commanded by Admiral Sir George Creasy were 197 Royal Navy warships, together with 13 from the Commonwealth and 16 from foreign navies, as well as representative vessels from the British Merchant Navy (United Kingdom), Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets. There were more British and Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were frigates or smaller vessels. Major Royal Navy units included Britain's last battleship, , and four fleet and three light aircraft carriers. The Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy also each included a light carrier in their contingents, and .