Constituent Monarchy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A non-sovereign monarchy or constituent monarchy is one in which the head of the

This situation can exist in a formal capacity, such as in the

This situation can exist in a formal capacity, such as in the

The

The

monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

polity (whether a geographic territory or an ethnic group), and the polity itself, are subject to a temporal authority higher than their own. The constituent states of the German Empire or the Princely States of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

provide historical examples; while the Zulu King

This article lists the Zulu monarchs, including chieftains and kings of the Zulu royal family from their earliest known history up to the present time.

Pre-Zulu

The Zulu King lineage stretches to as far as Luzumana, who is believed to have li ...

, whose power derives from the Constitution of South Africa, is a contemporary one.

Structure and forms

This situation can exist in a formal capacity, such as in the

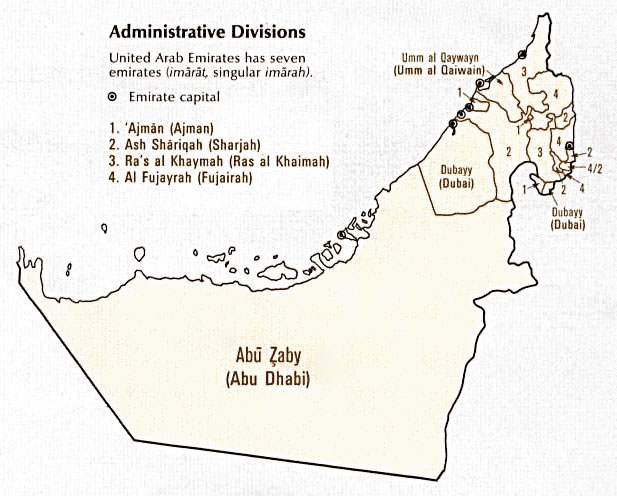

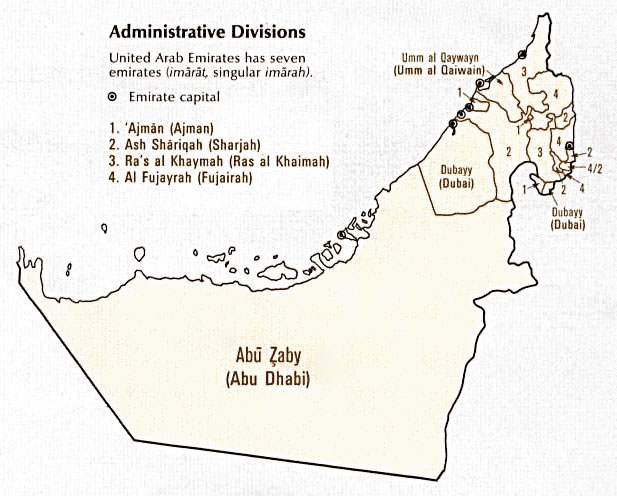

This situation can exist in a formal capacity, such as in the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at t ...

(in which seven historically independent Emirates now serve as constituent states of a federation, the President of which is chosen from among the Emirs), or in a more informal one, in which theoretically independent territories are in feudal suzerainty to stronger neighbors or foreign powers (the position of the princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

under the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

), and thus can be said to lack sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

in the sense that they cannot, for practical purposes, conduct their affairs of state unhampered. The most formalized arrangement is known as a federal monarchy

A federal monarchy, in the strict sense, is a federation of Country, states with a single monarch as overall head of the federation, but retaining Non-sovereign monarchy, different monarchs, or having a non-monarchical system of government, in ...

, in which the relationship between smaller constituent monarchies and the central government (which may or may not have a territory of its own) parallels that of states to a federal government in republics, such as the United States of America. Like sovereign monarchies, there exist both hereditary and elective non-sovereigns.

Systems of both formal and informal suzerainty were common before the 20th century, when monarchical systems were used by most states. During the last century, however, many monarchies have become republics, and those who remain are generally the formal sovereigns of their nations. Sub-national monarchies also exist in a few states which are, in and of themselves, not monarchical, (generally for the purpose of fostering national traditions).

The degree to which the monarchs have control over their polities varies greatly—in some they may have a great degree of domestic authority (as in the United Arab Emirates), while others have little or no policy-making power (the case with numerous ethnic monarchs today). In some, the monarch's position might be purely traditional or cultural in nature, without any formal constitutional authority at all.

Contemporary institutions

France

Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (; french: Wallis-et-Futuna or ', Fakauvea and Fakafutuna: '), is a French island collectivity in the South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji ...

is an overseas collectivity

The French overseas collectivities (''collectivité d'outre-mer'' or ''COM'') are first-order administrative divisions of France, like the French regions, but have a semi-autonomous status. The COMs include some former French overseas colonies ...

of the French Republic in Polynesia consisting of three main islands ( Wallis, Futuna, and the mostly uninhabited Alofi

Alofi is the capital of the Pacific Ocean island nation of Niue. With a population of 597 in 2017, Alofi has the distinction of being the second smallest national capital city in terms of population (after Ngerulmud, capital of Palau). It cons ...

) and a number of tiny islets. The collectivity is made up of three traditional kingdoms: Uvea

The uvea (; Lat. ''uva'', "grape"), also called the ''uveal layer'', ''uveal coat'', ''uveal tract'', ''vascular tunic'' or ''vascular layer'' is the pigmented middle of the three concentric layers that make up an eye.

History and etymolog ...

, on the island of Wallis, Sigave

Sigavé (also Singave or Sigave) is one of the three official chiefdoms of the French territory of Wallis and Futuna in Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. (The other two chiefdoms are Uvea and Alo.)

Geography Overview

Sigave encompasses the wes ...

, on the western part of the island of Futuna, and Alo, on the island of Alofi and on the eastern part of the island of Futuna. The current co-claimants to the title King of Uvea are Felice Tominiko Halagahu Felice is a name that can be used as both a given name, masculine or feminine, and a surname. It is a common name in Italian, where it is equivalent to Felix. Notable people with the name include:

Given name Arts and literature Film and theater

* ...

and Patalione Kanimoa

Patalione Kanimoa is a Wallisian politician from Wallis and Futuna, a French overseas collectivity in the South Pacific. He was President of the Territorial Assembly in the French government of the Wallis and Futuna. He was nominated by the Fren ...

, the current King of Alo is Filipo Katoa and the current King of Sigave is Eufenio Takala. They have been reigning since 2016.

The territory was annexed by the French Republic in 1888, and was placed under the authority of another French colony

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that exist ...

, New Caledonia. The inhabitants of the islands voted in a 1959 referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

to become an overseas collectivity of France, effective in 1961. The collectivity is governed as a parliamentary republic in which the citizens elect a Territorial Assembly, the President of which becomes the head of government. His cabinet, the Council of the Territory, is made up of the three Kings and three appointed ministers. In addition to this limited parliamentary role the Kings play, the individual kingdoms' customary legal systems

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

have some jurisdiction in areas of civil law.

Malaysia

A number of independent Muslim sultanates and tribal territories existed in the East Indies (the modern-day states of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Brunei) before the coming of colonial powers in the 16th century, the most prominent one in what is now Malaysia beingMelaka

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

. The first to establish colonies were the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, but they were eventually displaced by the more powerful Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and British. The 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty defined the borders between British possessions and the Dutch East Indies. The British controlled the Eastern half of modern Malaysia (in a variety of federations and colonies, see History of Malaysia) through a system of protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

s, in which native states had some domestic authority, checked by the British government. The eastern half of Malaysia was part of the independent Sultanate of Brunei until 1841, when it was granted independence as the Kingdom of Sarawak

(While I breathe, I hope)

, national_anthem = ''Gone Forth Beyond the Sea''

, capital = Kuching

, common_languages = English, Iban, Melanau, Bidayuh, Sarawak Malay, Chinese etc.

, government_type = Abso ...

under the White Rajas. The kingdom would remain fully independent until 1888, when it accepted British protectorate status, which it retained until the last Raja, Charles Vyner Brooke ceded his rights to the United Kingdom.

The two halves were united for the first time with the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Modern Malaysia is a federal monarchy

A federal monarchy, in the strict sense, is a federation of Country, states with a single monarch as overall head of the federation, but retaining Non-sovereign monarchy, different monarchs, or having a non-monarchical system of government, in ...

, consisting of 13 states (of which nine, known as the Malay States

The monarchies of Malaysia refer to the constitutional monarchy system as practised in Malaysia. The political system of Malaysia is based on the Westminster parliamentary system in combination with features of a federation.

Nine of the state ...

, are monarchical) and three federal territories. Of the Malay states, seven are sultanates (Johor

Johor (; ), also spelled as Johore, is a state of Malaysia in the south of the Malay Peninsula. Johor has land borders with the Malaysian states of Pahang to the north and Malacca and Negeri Sembilan to the northwest. Johor shares maritime ...

, Kedah

Kedah (), also known by its honorific Darul Aman and historically as Queda, is a state of Malaysia, located in the northwestern part of Peninsular Malaysia. The state covers a total area of over 9,000 km2, and it consists of the mainland ...

, Kelantan

Kelantan (; Jawi: ; Kelantanese Malay: ''Klate'') is a state in Malaysia. The capital is Kota Bharu and royal seat is Kubang Kerian. The honorific name of the state is ''Darul Naim'' (Jawi: ; "The Blissful Abode").

Kelantan is located in th ...

, Pahang

Pahang (; Jawi: , Pahang Hulu Malay: ''Paha'', Pahang Hilir Malay: ''Pahaeng'', Ulu Tembeling Malay: ''Pahaq)'' officially Pahang Darul Makmur with the Arabic honorific ''Darul Makmur'' (Jawi: , "The Abode of Tranquility") is a sultanate and ...

, Perak, Selangor

Selangor (; ), also known by its Arabic language, Arabic honorific Darul Ehsan, or "Abode of Sincerity", is one of the 13 Malaysian states. It is on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and is bordered by Perak to the north, Pahang to the east ...

and Terengganu

Terengganu (; Terengganu Malay: ''Tranung'', Jawi: ), formerly spelled Trengganu or Tringganu, is a sultanate and constitutive state of federal Malaysia. The state is also known by its Arabic honorific, ''Dāru l- Īmān'' ("Abode of Faith" ...

), one is a kingdom (Perlis

Perlis, ( Northern Malay: ''Peghelih''), also known by its honorific title Perlis Indera Kayangan, is the smallest state in Malaysia by area and population. Located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, it borders the Thai provinces ...

), one an elective monarchy ( Negeri Sembilan), while the remaining four states and the federal territories have non-monarchical systems of government. The head of state of the entire federation is a constitutional monarch styled Yang di-Pertuan Agong

The Yang di-Pertuan Agong (, Jawi: ), also known as the Supreme Head of the Federation, the Paramount Ruler or simply as the Agong, and unofficially as the King of Malaysia, is the constitutional monarch and head of state of Malaysia. The o ...

(In English, "He who is made lord"). The Yang di-Pertuan is elected to a five-year term by the Conference of Rulers

The Conference of Rulers (also Council of Rulers or Durbar, ms, Majlis Raja-Raja; Jawi: ) in Malaysia is a council comprising the nine rulers of the Malay states, and the governors or ''Yang di-Pertua Negeri'' of the other four states. It was ...

, made up of the nine state monarchs and the governors of the remaining states. A system of informal rotation exists between the nine state monarchs.

New Zealand

The

The Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

of New Zealand lived in the autonomous territories of numerous tribes, called ''iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori roughly means "people" or "nation", and is often translated as "tribe", or "a confederation of tribes". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, ...

'', before the arrival of British colonialists in the mid 19th century. The Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the History of New Zealand, history, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in ...

, signed in 1840 by about a third of the Māori chiefs, made the Māori British subjects in return for (theoretical) autonomy and preservation of property rights. British encroachment on tribal lands continued, however, leading to the creation of the King Movement (Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

: ''Kīngitanga'') in an attempt to foster strength through intertribal unity. Numerous tribal chiefs refused the mantle of King, but the leader of the Tainui

Tainui is a tribal waka confederation of New Zealand Māori iwi. The Tainui confederation comprises four principal related Māori iwi of the central North Island of New Zealand: Hauraki, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa and Waikato.

There are ...

iwi, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero

Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (died 25 June 1860) was a Māori warrior, leader of the Waikato iwi (confederation of tribes), the first Māori King and founder of the Te Wherowhero royal dynasty. He was first known just as ''Te Wherowhero'' and took th ...

, was persuaded, and was crowned as the Māori King in 1857. The federation of tribes supporting the King fought against the British during the territorial conflicts known as the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the ...

(which resulted in the confiscation of four million acres (16,000 km²) of tribal land), not emerging from their refuge in the rural region known as King Country

The King Country (Māori: ''Te Rohe Pōtae'' or ''Rohe Pōtae o Maniapoto'') is a region of the western North Island of New Zealand. It extends approximately from the Kawhia Harbour and the town of Otorohanga in the north to the upper reaches of ...

until 1881.

The position of the Māori monarch has never had formal authority or constitutional status in New Zealand ( which is itself a constitutional monarchy, as a Commonwealth realm). Before its defeat in the Land Wars, however, the King Movement wielded temporal authority over large parts of the North Island and possessed some of the features of a state, including magistrates, a state newspaper known as Te Hokioi, and government ministers (there was even a minister of Pākehā affairs being the Māori term for Europeans. A parliament, the Kauhanganui, was set up at Maungakawa, near Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, in 1889 or 1890. Today, though the monarch lacks political power, the position is invested with a great deal of mana

According to Melanesian and Polynesian mythology, ''mana'' is a supernatural force that permeates the universe. Anyone or anything can have ''mana''. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of energy and power, rather than being ...

(cultural prestige). The monarchy is elective in theory, in that there is no official dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

or order of succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.Te Arikinui Tuheitia Paki. He was crowned on 21 August 2006, following the death on 15 August of his mother, Queen

The Zulu Kingdom was the independent

The Zulu Kingdom was the independent

The numerous small sheikdoms on the Persian Gulf were under informal suzerainty to the

The numerous small sheikdoms on the Persian Gulf were under informal suzerainty to the

In 1888, during the Scramble for Africa, the powerful Bantu

In 1888, during the Scramble for Africa, the powerful Bantu

Te Atairangikaahu

Dame Te Atairangikaahu (23 July 1931 – 15 August 2006) was the Māori queen for 40 years, the longest reign of any Māori monarch. Her full name and title was Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu. Her title Te Arikinui (meaning ''Paramount ...

, whose forty-year reign was the longest of any Māori monarch.

Nigeria

The non-sovereign monarchs ofNigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, known locally as the traditional rulers, serve the twin contemporary functions of fostering traditional preservation in the wake of globalisation and representing their people in their dealings with the official government, which in turn serves to recognise their titles. They have very little in the way of technical authority, but are in possession of real influence in practice due to their control of popular opinion within the various tribes. In addition to this a number of them, such as the Sultan of Sokoto

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

and the Ooni

The Ooni of Ile-Ife (Ọọ̀ni of Ilè-Ifẹ̀) is the traditional ruler of Ile-Ife and the spiritual head of the Yoruba people. The Ooni dynasty existed before the reign of Oduduwa which historians have argued to have been between the 7th- ...

of Ife, retain their spiritual authority as religious leaders of significant parts of the country in question's population.

South Africa

The Zulu Kingdom was the independent

The Zulu Kingdom was the independent nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

of the Zulu people

Zulu people (; zu, amaZulu) are a Nguni ethnic group native to Southern Africa. The Zulu people are the largest ethnic group and nation in South Africa, with an estimated 10–12 million people, living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Nata ...

, founded by Shaka kaSenzangakhona

Shaka kaSenzangakhona ( – 22 September 1828), also known as Shaka Zulu () and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms tha ...

in 1816. The Kingdom was a major regional power for most of the 19th century, but eventually was drawn into conflict with the expanding British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, and after a reduction in territory after defeat in the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

, lost its independence in 1887, when it was incorporated into the Natal Colony

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies to ...

, and later the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

.

The Zulu King

This article lists the Zulu monarchs, including chieftains and kings of the Zulu royal family from their earliest known history up to the present time.

Pre-Zulu

The Zulu King lineage stretches to as far as Luzumana, who is believed to have li ...

s remained pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term is often used to suggest that a claim is not legitimate.Curley Jr., Walter J. P. ''Monarchs-in-Waiting'' ...

s to their officially abolished thrones during the 20th century, but were granted official authority by the Traditional Leadership Clause of the republican Constitution of South Africa

The Constitution of South Africa is the supreme law of the Republic of South Africa. It provides the legal foundation for the existence of the republic, it sets out the rights and duties of its citizens, and defines the structure of the Gover ...

. The constitution recognizes the right of "traditional authorities" to operate by and amend systems of customary law, and directs the courts to apply these laws as applicable. It also empowers the national and provincial legislatures to formally establish houses for and councils of traditional leaders. The Zulu King is head of this council of tribal chiefs, known as the Ubukhosi.

The current Zulu King is Misuzulu Zulu

King Misuzulu Sinqobile kaZwelithini (born 23 September 1974) is the reigning King of the Zulu nation. While Misuzulu is the third oldest surviving son of King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu, he is the first son of King Goodwill Zwelithini's ...

, who reigns as King of the Zulu ''nation'', rather than of Zululand, which is today part of the South African province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of KwaZulu-Natal. Zulu ascended the throne in 2021.

United Arab Emirates

The numerous small sheikdoms on the Persian Gulf were under informal suzerainty to the

The numerous small sheikdoms on the Persian Gulf were under informal suzerainty to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

during the 16th century. Later, this dominance gradually shifted to the United Kingdom. In 1853 the rulers signed a Perpetual Maritime Truce

The Perpetual Maritime Truce of 1853 was a treaty signed between the British and the Rulers of the Sheikhdoms of the Lower Gulf, later to become known as the Trucial States and today known as the United Arab Emirates. The treaty followed the effe ...

, and from that point onward delegated disputes between themselves to the British for arbitration (it is from this arrangement that the territory's former title, the "Trucial" States was derived). In 1892 this arrangement was formalized into a protectorate in which the British assumed responsibility for the emirate's protection. This arrangement existed until 1971, when the UAE was granted independence.

The U.A.E.'s system of governance is unique, in that while the seven constituent emirates are all absolute monarchies, the structure of the federal government itself is not (theoretically, at least) monarchical, as it is in Malaysia. Instead, the formal governmental structure has features of both semi-presidential

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

and parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

systems, with some modifications. In purely parliamentary systems the legislature elects the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, ...

(the Prime Minister) and can force their resignation, and that of the cabinet, through a no-confidence vote, while the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

is generally appointed or hereditary position without practical power (such as a constitutional monarch or Governor General); in semi-presidential systems the head of state (a President) is popularly elected and takes a role in governing alongside the head of government, though his cabinet is still accountable to the legislature and can be forced to resign.

The U.A.E does possess a weak legislature, called the National Federal Council, which is partially elected and partially appointed, but neither the legislature nor the population at large has a hand in determining the country's political leadership. In the U.A.E., it is the Federal Supreme Council (a sort of "upper" cabinet made up of the seven Emirs), which elects both the head of state (the President) and the head of government (the Prime Minister), both of whom have considerable governing power, to five year terms. This is a purely formal election, however (similar to the later royal elections of Polish kings

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

), as the rulers of the two largest and wealthiest Emirates, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, have always held the posts of President and Prime Minister, respectively. This Council also elects the lower cabinet, the Council of Ministers, as well as the judges of Supreme Court.

The seven constituent Emirates of the U.A.E. are Abu Dhabi, Ajman

Ajman ( ar, عجمان, '; Gulf Arabic: عيمان ʿymān) is the capital of the emirate of Ajman in the United Arab Emirates. It is the fifth-largest city in UAE after Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Sharjah and Al Ain. Located along the Persian Gulf, i ...

, Dubai

Dubai (, ; ar, دبي, translit=Dubayy, , ) is the most populous city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the capital of the Emirate of Dubai, the most populated of the 7 emirates of the United Arab Emirates.The Government and Politics of ...

, Fujairah

Fujairah City ( ar, الفجيرة) is the capital of the emirate of Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates. It is the seventh-largest city in UAE, located on the Gulf of Oman (part of the Indian Ocean). It is the only Emirati capital city on the ...

, Ras al-Khaimah

Ras Al Khaimah (RAK) ( ar, رَأْس ٱلْخَيْمَة, historically Julfar) is the largest city and capital of the Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates. It is the sixth-largest city in UAE after Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Al A ...

, Sharjah

Sharjah (; ar, ٱلشَّارقَة ', Gulf Arabic: ''aš-Šārja'') is the third-most populous city in the United Arab Emirates, after Dubai and Abu Dhabi, forming part of the Dubai-Sharjah-Ajman metropolitan area.

Sharjah is the capital ...

, and Umm al-Quwain

Umm Al Quwain is the capital and largest city of the Emirate of Umm Al Quwain in the United Arab Emirates.

The city is located on the peninsula of Khor Al Bidiyah, with the nearest major cities being Sharjah to the southwest and Ras Al Khaimah ...

.

Uganda

In 1888, during the Scramble for Africa, the powerful Bantu

In 1888, during the Scramble for Africa, the powerful Bantu Kingdom of Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Buganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala. The 14 m ...

was placed under the administration of the Imperial British East Africa Company

The Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was a commercial association founded to develop African trade in the areas controlled by the British Empire. The company was incorporated in London on 18 April 1888 and granted a royal charter by Q ...

. In 1894, however, the company relinquished its rights to the territory to the British government, which expanded its control to the neighboring Kingdoms of Toro, Ankole, Busoga, Bunyoro

Bunyoro or Bunyoro-Kitara is a Bantu kingdom in Western Uganda. It was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa from the 13th century to the 19th century. It is ruled by the King ('' Omukama'') of Bunyoro-Kitara. The cur ...

and tribal territories in establishing the Uganda Protectorate

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the Bri ...

, which was maintained until independence was granted in 1961.

Upon achieving independence, Uganda became a republic, and its first years were characterized by a power struggle between the Uganda People's Congress

The Uganda People's Congress (UPC; sw, Congress ya Watu wa Uganda) is a political party in Uganda.

UPC was founded in 1960 by Milton Obote, who led the country to independence and later served two presidential terms under the party's banner ...

and the Bugandan nationalist and monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

Kabaka Yekka Party. Edward Muteesa II, the King of Buganda, was appointed President and commander of the armed forces, but in 1967 Prime Minister Apollo Milton Obote staged a coup against the Bugandan King in the Battle of Mengo Hill. During Obote's subsequent rule the monarchies were abolished, and remained so during the rule of Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

as well.

Restoration of the traditional monarchies came in 1993. The restored monarchies are cultural in nature, and their Kings do not have policy-making power. The Kingdom of Rwenzururu, which did not exist before the 1966 abolition, was officially established in 2008. The areas which now make up the Kingdom were formerly part of the Kingdom of Toro. The region is populated by Konjo and Amba

Amba or AMBA may refer to:

Title

* Amba Hor, alternative name for Abhor and Mehraela, Christian martyrs

* Amba Sada, also known as Psote, Christian bishop and martyr in Upper Egypt

Given name

* Amba, the traditional first name given to the first ...

peoples, whose territory was incorporated into the Kingdom of Toro by the British. A secession movement existed during Uganda's early years of independence, and after a 2005 report from the Ugandan government found that the great majority of the regions inhabitants favored the creation of a Rwenzururu monarchy, the Kingdom was recognized by the Ugandan cabinet on March 17, 2008.

References

{{Reflist