Conspiracy theories about Adolf Hitler's death on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In October 1945, ''

In October 1945, ''

Neither former Soviet nor Russian officials have claimed the skull was the main piece of evidence, instead citing jawbone fragments and two dental bridges found in May 1945. The items were shown to two associates of Hitler's personal dentist,

Neither former Soviet nor Russian officials have claimed the skull was the main piece of evidence, instead citing jawbone fragments and two dental bridges found in May 1945. The items were shown to two associates of Hitler's personal dentist,

Some works claim that Hitler and Braun did not commit suicide, but actually escaped to Argentina.

Some works claim that Hitler and Braun did not commit suicide, but actually escaped to Argentina.

FBI documents containing alleged sightings of Hitler

{{Nazis South America 1945 in Germany Hitler, Adolf Death of Adolf Hitler Nazis in South America Views on Adolf Hitler fr:Derniers jours d'Adolf Hitler#Rumeurs sur la fuite d'Hitler

Conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

about the death of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, dictator of Germany from 1933 to 1945, contradict the accepted fact that he committed suicide in the ''Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ...

'' on 30 April 1945. Stemming from a campaign of Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the ...

, most of these theories hold that Hitler and his wife, Eva Braun

Eva Anna Paula Hitler (; 6 February 1912 – 30 April 1945) was a German photographer who was the longtime companion and briefly the wife of Adolf Hitler. Braun met Hitler in Munich when she was a 17-year-old assistant and model for his ...

, survived and escaped from Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, with some asserting that he went to South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. In the post-war years, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

(FBI) and Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) investigated some of the reports, without lending them credence. The 2009 revelation that a skull in the Soviet archives long (dubiously) claimed to be Hitler's actually belonged to a woman has helped fuel conspiracy theories.

While the claims have received some exposure in popular culture, they are regarded by historians and scientific experts as disproven fringe theories

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint which differs from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such ...

. Eyewitnesses and Hitler's dental remains demonstrate that he died in his Berlin bunker in 1945.

Origins

The narrative that Hitler did not commit suicide, but instead escaped Berlin, was first presented to the general public by MarshalGeorgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

at a press conference on 9 June 1945, on orders from Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

. That month, 68% of Americans polled thought Hitler was still alive. When asked at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

in July 1945 how Hitler had died, Stalin said he was either living "in Spain or Argentina." In July 1945, British newspapers repeated comments from a Soviet officer that a charred body discovered by the Soviets was "a very poor double." American newspapers also repeated dubious quotes, such as that of the Russian garrison commandant of Berlin, who claimed that Hitler had "gone into hiding somewhere in Europe." This disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the ...

, propagated by Stalin's government, has been a springboard for various conspiracy theories, despite the official conclusion by Western powers and the consensus of historians that Hitler killed himself on 30 April 1945. It even caused a minor resurgence in Nazism during the Allied occupation of Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

.

In October 1945, ''

In October 1945, ''France-Soir

''France Soir'' ( en, France Evening) was a French newspaper that prospered in physical format during the 1950s and 1960s, reaching a circulation of 1.5 million in the 1950s. It declined rapidly under various owners and was relaunched as a popu ...

'' quoted Otto Abetz, Nazi ambassador to Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

during World War II, as saying that Hitler was not dead. The first detailed investigation by Western powers began that November after Dick White

Sir Dick Goldsmith White, (20 December 1906 – 21 February 1993) was a British intelligence officer. He was Director General (DG) of MI5 from 1953 to 1956, and Head of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) from 1956 to 1968.

Early life

Whi ...

, then head of counter-intelligence in the British sector of Berlin, had their agent Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper was a polemicist and essayist on a range of ...

investigate the matter to counter the Soviet claims. His findings that Hitler and Braun had died by suicide in Berlin were written in a report in 1946, and published in a book the next year. Regarding the case, Trevor-Roper reflected, "the desire to invent legends and fairy tales... is (greater) than the love of truth". In April 1947, 45% of Americans polled thought Hitler was still alive.

In 1946, an American miner and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

preacher named William Henry Johnson began sending out a series of letters under the pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Furrier No. 1", claiming to be the living Hitler and to have escaped with Braun to Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. He alleged that tunnels were being dug to Washington, D.C., and that he would engage armies, nuclear bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

and invisible spaceships to take over the universe. Johnson was able to raise up to $15,000 (over $140,000 in 2020 currency), promising lofty incentives to his supporters, before being arrested on charges of mail fraud

Mail fraud and wire fraud are terms used in the United States to describe the use of a physical or electronic mail system to defraud another, and are federal crimes there. Jurisdiction is claimed by the federal government if the illegal activity ...

in mid-1956.

In March 1948, newspapers around the world reported the account of former German lieutenant Arthur F. Mackensen, who claimed that on 5 May 1945 (during the Soviet bombardment of Berlin), he, Hitler, Braun and Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

had escaped the ''Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ...

'' in tanks. The group allegedly flew from Tempelhof Airport

Berlin Tempelhof Airport (german: Flughafen Berlin-Tempelhof) was one of the first airports in Berlin, Germany. Situated in the south-central Berlin borough of Tempelhof-Schöneberg, the airport ceased operating in 2008 amid controversy, leav ...

to Tondern, Denmark, where Hitler gave a speech and took a flight with Braun to the coast. In a May 1948 issue of the Italian magazine ''Tempo'', author Emil Ludwig wrote that a double could have been cremated in Hitler's place, allowing him to flee by submarine to Argentina. Presiding judge at the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg Michael Musmanno

Michael Angelo Musmanno (April 7, 1897 – October 12, 1968) was an American jurist, politician, and naval officer. Coming from an immigrant family, he started to work as a coal loader at the age of 14. After serving in the United States Army in ...

wrote in his 1950 book that such theories were "about as rational as to say that Hitler was carried away by angels," citing a lack of evidence, the confirmation of Hitler's dental remains, and the fact that Ludwig had expressly ignored the presence of witnesses in the bunker. In his refutation of Mackensen's account, Musmanno cites a subsequent story of his, in which the lieutenant allegedly flew on 9 May to Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

, Spain, when he was attacked by 30 Lightning fighters

is a vertically scrolling shooter arcade video game by Konami released in 1990. It was published in the US and Europe as ''Lightning Fighters''.

Development

The three composers for the game were also working on the music for the Famicom title ...

over Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

(despite the war having ended in Europe), purportedly killing all 33 passengers besides himself.

From 1951 to 1972, the ''National Police Gazette

The ''National Police Gazette'', commonly referred to as simply the ''Police Gazette'', is an American magazine founded in 1845. Under publisher Richard K. Fox, it became the forerunner of the men's lifestyle magazine, the illustrated sports w ...

'', an American tabloid-style magazine, ran a series of stories asserting Hitler's survival. Unproven allegations include that Hitler conceived children with Braun around the late 1930s, that he was actually in prime physical health

Health, according to the World Health Organization, is "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity".World Health Organization. (2006)''Constitution of the World Health Organi ...

at the end of World War II, and that he fled to Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

or South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. Writing for the ''Gazette'', US intelligence officer William F. Heimlich

William F. "Bill" Heimlich (September 28, 1911 - June 1, 1996) was an American intelligence officer and director of the RIAS (''Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor'', "Radio in the American Sector") after World War II.

Life and career

Heimlich, a ...

claimed that the blood found on Hitler's sofa did not match his blood type

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is a classification of blood, based on the presence and absence of antibodies and inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates ...

.

Following decades of other contradictory reports, in 1968 Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski released his book ''The Death of Adolf Hitler

''The Death of Adolf Hitler: Unknown Documents from Soviet Archives'' (german: Der Tod des Adolf Hitler: Unbekannte Dokumente aus Moskauer Archiven, links=no) is a 1968 book by Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski, who served as an interpreter in t ...

''. It includes a purported Soviet autopsy report which concludes that Hitler died by cyanide poisoning

Cyanide poisoning is poisoning that results from exposure to any of a number of forms of cyanide. Early symptoms include headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and vomiting. This phase may then be followed by seizures, ...

, despite no dissection of internal organs being recorded to confirm this and eyewitness accounts to the contrary. Bezymenski claims that the autopsy reports were not released earlier "in case someone might try to slip into the role of 'the Führer saved by a miracle.'" He later admitted that he was acting as "a typical party propagandist" and intended "to lead the reader to the conclusion that gunshotwas a pipe dream or half an invention and that Hitler actually poisoned himself." The book's claims have been widely derided by Western historians.

In 2020, historian Richard J. Evans wrote:

For some on thefar right Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of bein ...it seems inconceivable that itlerwould have died such a cowardly and ignominious death. ... In some cases, the proponents of Hitler's survival have strong links to theneo-Nazi Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), attack ...scene, or betray beliefs, or are involved with white supremacy organisations in the US that regard Hitler as an inspiration for their activities. ... Somefringe Fringe may refer to: Arts * Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world's largest arts festival, known as "the Fringe" * Adelaide Fringe, the world's second-largest annual arts festival * Fringe theatre, a name for alternative theatre * The Fringe, the ...groups purveying various forms of 'alternative' knowledge, such asoccult The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...ists orUFO An unidentified flying object (UFO), more recently renamed by US officials as a UAP (unidentified aerial phenomenon), is any perceived aerial phenomenon that cannot be immediately identified or explained. On investigation, most UFOs are ide ...enthusiasts, seem to think that associating their beliefs with Hitler will gain them attention. So in some versions of the survival myth, Hitler's escape was achieved by occult means, or involved his travelling to a secret Nazi flying saucer base beneath the Antarctic ice.

Evidence

At the end of 1945, Stalin ordered a second commission to investigate Hitler's death, in part to investigate rumours of Hitler's survival. On 30 May 1946, part of a skull was found, ostensibly in the crater where Hitler's remains had been exhumed. It consists of part of theoccipital bone

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cer ...

and part of both parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, and four angles. It is n ...

s. The nearly complete left parietal bone has a bullet hole, apparently an exit wound. In 2009, on an episode of History

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

's ''MysteryQuest

''MysteryQuest'' is an American Paranormal television series that premiered on September 16, 2009 on History. Produced by KPI Productions, the program is a spin-off of ''MonsterQuest''. The series tag line is "What if everything you believe i ...

'', University of Connecticut

The University of Connecticut (UConn) is a public land-grant research university in Storrs, Connecticut, a village in the town of Mansfield. The primary 4,400-acre (17.8 km2) campus is in Storrs, approximately a half hour's drive from H ...

archaeologist and bone specialist Nick Bellantoni examined the skull fragment, which Soviet officials had believed to be Hitler's. According to Bellantoni, "The bone seemed very thin" for a male, and "the sutures where the skull plates come together seemed to correspond to someone under 40". A small piece detached from the skull was DNA-tested, as was blood from Hitler's sofa. The skull was determined to be that of a woman—providing fodder for conspiracy theorists—while the blood was confirmed to belong to a male.

Neither former Soviet nor Russian officials have claimed the skull was the main piece of evidence, instead citing jawbone fragments and two dental bridges found in May 1945. The items were shown to two associates of Hitler's personal dentist,

Neither former Soviet nor Russian officials have claimed the skull was the main piece of evidence, instead citing jawbone fragments and two dental bridges found in May 1945. The items were shown to two associates of Hitler's personal dentist, Hugo Blaschke

Hugo Johannes Blaschke (14 November 1881 – 6 December 1959) was a German dental surgeon notable for being Adolf Hitler's personal dentist from 1933 to April 1945 and for being the chief dentist on the staff of ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich Him ...

: his assistant Käthe Heusermann and longtime dental technician Fritz Echtmann. They confirmed that the dental remains were Hitler's and Braun's, as did Blaschke in later statements. According to Ada Petrova and Peter Watson, Hugh Thomas disputed these dental remains in his 1995 book, but also speculated that Hitler probably died in the bunker after being strangled by his valet Heinz Linge. They noted that "even Dr Thomas admits that there is no evidence to support" this theory. Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

wrote that "The 'theories' of Hugh Thomas ... that Hitler was strangled by Linge, and that the female body burned was not that of Eva Braun, who escaped from the bunker, belong in fairyland." In 2017, French forensic pathologist Philippe Charlier

Philippe Charlier is a French coroner, forensic pathologist and paleopathologist.

Biography

Charlier was born in Meaux on 25 June 1977. His father is a doctor, his mother a pharmacist. He made his first dig at the age of 10, when he found a hu ...

confirmed that teeth on one of the jawbone fragments were in "perfect agreement" with an taken of Hitler in 1944. This investigation of the teeth by the French team, the results of which were reported in the '' European Journal of Internal Medicine'' in May 2018, found that the dental remains were definitively Hitler's teeth. According to Charlier, "There is no possible doubt. Our study proves that Hitler died in 1945 n Berlin"

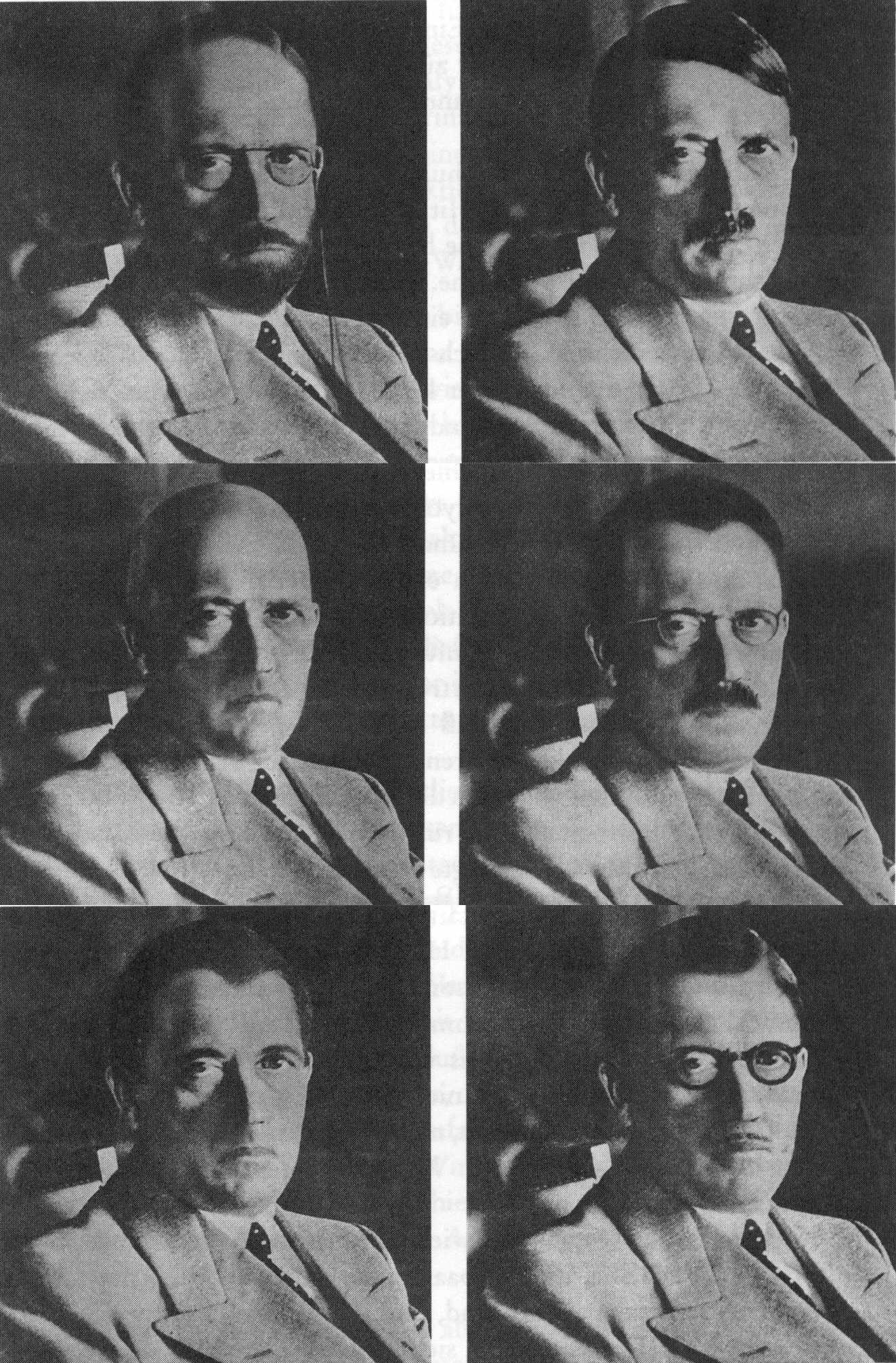

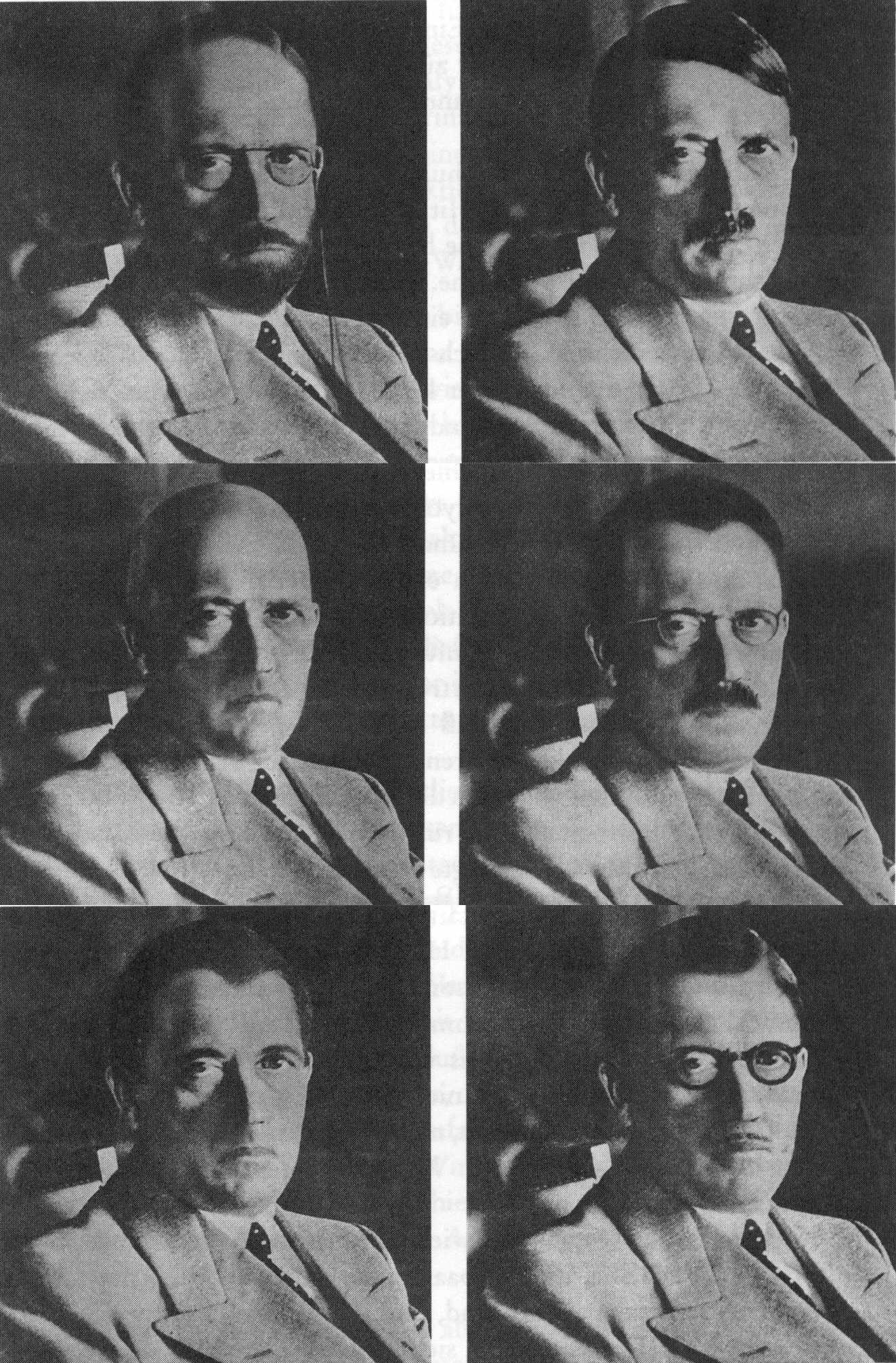

FBI documents declassified by the 1998 Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, which began to be released online by the early 2010s, contain a number of alleged sightings of Hitler in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, South America, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, some of which assert that he changed his appearance via plastic surgery

Plastic surgery is a surgical specialty involving the restoration, reconstruction or alteration of the human body. It can be divided into two main categories: reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery. Reconstructive surgery includes cranio ...

or by shaving off his toothbrush moustache

The toothbrush moustache is a style of moustache in which the sides are vertical (or nearly vertical) rather than tapered, giving the hairs the appearance of the bristles on a toothbrush that are attached to the nose. It was made famous by such ...

. Although some notable individuals speculated that Hitler could have survived, including General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower and Lieutenant John F. Kennedy in mid-1945, the documents state that the alleged sightings of Hitler could not be verified. Richard J. Evans notes that the FBI was obliged to document such claims no matter how "erroneous or deranged" they were, while American historian Donald McKale states that their files did not produce any credible indication of Hitler's survival.

In spite of the disinformation from Stalin's government and eyewitness discrepancies, the consensus of historians is that Hitler killed himself on 30 April 1945.

Alleged escape to Argentina

Some works claim that Hitler and Braun did not commit suicide, but actually escaped to Argentina.

Some works claim that Hitler and Braun did not commit suicide, but actually escaped to Argentina.

Phillip Citroen's claims

A declassifiedCIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

document dated 3 October 1955 reported claims made by a self-proclaimed former German SS trooper named Phillip Citroen that Hitler was still alive, and that he "left Colombia for Argentina around January 1955." Enclosed with the document was an alleged photograph of Citroen and a person he claimed to be Hitler; on the back of the photo was written "Adolf Schüttelmayor" and the year 1954. The report also states that neither the contact who reported his conversations with Citroen, nor the CIA station was "in a position to give an intelligent evaluation of the information". The station chief's superiors told him that "enormous efforts could be expended on this matter with remote possibilities of establishing anything concrete", and the investigation was dropped.

''Grey Wolf''

The 2011 book '' Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler'' by British authors Simon Dunstan and Gerrard Williams, and the 2014 docudrama film by Williams based on it, suggest that a number of took certain Nazis andNazi loot

Nazi plunder (german: Raubkunst) was the stealing of art and other items which occurred as a result of the organized looting of European countries during the time of the Nazi Party in Germany. The looting of Polish and Jewish property was a k ...

to Argentina, where the Nazis were supported by future president Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected ...

, who, with his wife " Evita", had been receiving money from the Nazis for some time. As claims received by the FBI stated, Hitler allegedly arrived in Argentina, first staying at Hacienda San Ramón (east of San Carlos de Bariloche

San Carlos de Bariloche, usually known as Bariloche (), is a city in the province of Río Negro, Argentina, situated in the foothills of the Andes on the southern shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake. It is located within the Nahuel Huapi National Park ...

), then moved to a Bavarian-style mansion at Inalco, a remote and barely accessible spot at the northwest end of Nahuel Huapi Lake

Nahuel Huapi Lake ( es, Lago Nahuel Huapí) is a lake in the lake region of northern Patagonia between the provinces of Río Negro Province, Río Negro and Neuquén Province, Neuquén, in Argentina. The tourist center of Bariloche is on the so ...

, close to the Chilean border. Supposedly, Eva Braun left Hitler around 1954 and moved to Neuquén

Neuquén (; arn, Nehuenken) is the capital city of the Argentine province of Neuquén and of the Confluencia Department, located in the east of the province. It occupies a strip of land west of the confluence of the Limay and Neuquén rivers w ...

with their daughter, Ursula ('Uschi'), and Hitler died in February 1962.Dunstan, Simon and Williams, Gerrard. (2011) ''Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler''. New York: Sterling Publishing.

This theory of Hitler's flight to Argentina has been dismissed by historians, including Guy Walters

Guy Edward Barham Walters (born 8 August 1971) is a British author, historian, and journalist. He is the author and editor of nine books on the Second World War, including war thrillers, and a historical analysis of the Berlin Olympic Games.

...

. He has described Dunstan and Williams' theory as "rubbish", adding: "There's no substance to it at all. It appeals to the deluded fantasies of conspiracy theorists and has no place whatsoever in historical research." Walters contended that "it is simply impossible to believe that so many people could keep such a grand scale deception so quiet," and says that no serious historian would give the story any credibility. Historian Richard Evans has many misgivings about the book and subsequent film. For example, he notes that the story about Ursula or 'Uschi' is merely "second-hand hearsay evidence without identification or corroboration." Evans also notes that Dunstan and Williams made extensive use of a book ''Hitler murió en la Argentina'' by Manuel Monasterio, which the author later admitted included made up 'strange ramblings', and speculation. Evans contends that Monasterio's book is not to be regarded as a reliable source. In the end, Evans dismisses the survival stories of Hitler as "fantasies". McKale notes that the book repeats many claims made over the preceding decades which are implied by remote association, stating that " en one has no factual or otherwise reliable proof, one resorts to associating... with something else or to using hearsay and other dubious evidence, including unnamed or unidentified sources."

''Hunting Hitler''

Investigators of theHistory Channel

History (formerly The History Channel from January 1, 1995 to February 15, 2008, stylized as HISTORY) is an American pay television network and flagship channel owned by A&E Networks, a joint venture between Hearst Communications and the Disney ...

series ''Hunting Hitler

''Hunting Hitler'' is a History Channel television series based on Conspiracy theories about Adolf Hitler's death, the premise that Adolf Hitler escaped from the ''Führerbunker'' in Berlin at the end of World War II. The show was conceived foll ...

'' (2015–2018) claim to have found declassified documents and to have interviewed witnesses indicating that Hitler escaped from Germany and travelled to South America by . He and other Nazis then allegedly plotted a "Fourth Reich

The Fourth Reich (german: Viertes Reich) is a hypothetical Nazi Reich that is the successor to Adolf Hitler's Third Reich (1933–1945). The term has also been used to refer to the possible resurgence of Nazi ideas, as well as pejoratively of pol ...

". Such conspiracy theories of survival and escape have been widely dismissed. Contradictorily, in 2017 the series was praised by the tabloid-style ''National Police Gazette'', which historically was a supporter of the fringe theory, while calling on Russia to allow Hitler's jawbone remains to be DNA-tested. After being featured on the series as an expert on World War II, author James Holland explained that " was ''very'' careful never to mention on film that I thought either Hitler or Bormann escaped. Because they didn't."

In popular culture

* In the adventure novel ''On the World's Roof'' (1949) byDouglas Valder Duff

Douglas Valder Duff DSC (1901, Rosario de Santa Fe, Argentina – 23 September 1978, Dorchester, England) was a British merchant seaman, Royal Navy officer, police officer, and author of over 100 books, including memoirs and books for children. ...

, a group of escaped Nazi officers with their Leader (purportedly Hitler himself) plan to bombard capital cities around the world with nuclear weapons from their stronghold in Tibet.

* In the 1981 novella '' The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H.'' by George Steiner

Francis George Steiner, FBA (April 23, 1929 – February 3, 2020) was a Franco-American literary critic, essayist, philosopher, novelist, and educator. He wrote extensively about the relationship between language, literature and society, and the ...

, Hitler survives the end of the war and escapes to the Amazon jungle, where he is found and tried by Nazi-hunters 30 years later. Hitler's defence is that since Israel owes its existence to the Holocaust, he is really the benefactor of the Jews.

*In the novel ''The Berkut

''The Berkut'' is a 1987 secret history novel by Joseph Heywood in which Adolf Hitler survives World War II. It is set in the period immediately after the fall of The Third Reich. This book pits a German colonel and a Russian soldier from a secre ...

'' (1987), Hitler escapes from Berlin with the intention of reaching South America, but is secretly captured by elite Soviet commandos under Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's orders. He is imprisoned in Moscow and later executed.

*In a 1995 ''The Simpsons

''The Simpsons'' is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The series is a satirical depiction of American life, epitomized by the Simpson family, which consists of Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa, ...

'' episode, "Bart vs. Australia

"Bart vs. Australia" is the sixteenth episode of the sixth season of the American animated television series ''The Simpsons''. It originally aired on the Fox network in the United States on February 19, 1995. In the episode, Bart is indicted fo ...

", Bart Simpson makes a call to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, which is received by elderly Adolf Hitler.

* In the 1999 video game '' Persona 2: Innocent Sin'', a rumor is spread that Hitler was saved by elite soldiers and fled with those soldiers to Antarctica, resulting in this "Last Battalion" taking over Sumaru City. Unlike most depictions of Hitler's survival beyond 1945, this is not actually true within the story's context; the story concerns rumors becoming reality, and the "Hitler" the party fights turns out to be Nyarlathotep

Nyarlathotep is a fictional character created by H. P. Lovecraft. The character is a malign deity in the Cthulhu Mythos, a shared universe. First appearing in Lovecraft's 1920 prose poem "Nyarlathotep", he was later mentioned in other works by ...

in disguise.

* In the CGI anime film '' Lupin III: The First'' (2019), Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an international organization that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and cri ...

spreads a fake rumor stating that Hitler is alive and living in Brazil, in order to lure his fanatical Ahnenerbe

The Ahnenerbe (, ''ancestral heritage'') operated as a think tank in Nazi Germany between 1935 and 1945. Heinrich Himmler, the ''Reichsführer-SS'' from 1929 onwards, established it in July 1935 as an SS appendage devoted to the task of promot ...

followers out of hiding.

* In the 2020 Amazon Prime

Amazon Prime is a paid subscription service from Amazon which is available in various countries and gives users access to additional services otherwise unavailable or available at a premium to other Amazon customers. Services include same, one- ...

TV-series ''Hunters

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/ hide, bone/tusks, horn/antler, et ...

'', it is discovered in 1977 that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun are living in Argentina.

References

Informational notes Citations Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Further reading *External links

FBI documents containing alleged sightings of Hitler

{{Nazis South America 1945 in Germany Hitler, Adolf Death of Adolf Hitler Nazis in South America Views on Adolf Hitler fr:Derniers jours d'Adolf Hitler#Rumeurs sur la fuite d'Hitler