Columbanus Community Of Reconciliation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an

King Agilulf gave Columbanus a tract of land called

King Agilulf gave Columbanus a tract of land called

During the last year of his life, Columbanus received messenges from King

During the last year of his life, Columbanus received messenges from King

In the fourth chapter, Columbanus presents the virtue of poverty and of overcoming greed, and that monks should be satisfied with "small possessions of utter need, knowing that greed is a leprosy for monks". Columbanus also instructs that "nakedness and disdain of riches are the first perfection of monks, but the second is the purging of vices, the third the most perfect and perpetual love of God and unceasing affection for things divine, which follows on the forgetfulness of earthly things. Since this is so, we have need of few things, according to the word of the Lord, or even of one." In the fifth chapter, Columbanus warns against vanity, reminding the monks of Jesus' warning in Luke 16:15: "You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of others, but God knows your hearts. What people value highly is detestable in God's sight." In the sixth chapter, Columbanus instructs that "a monk's chastity is indeed judged in his thoughts" and warns, "What profit is it if he be virgin in body, if he be not virgin in mind? For God, being Spirit."

In the seventh chapter, Columbanus instituted a service of perpetual prayer, known as ''

In the fourth chapter, Columbanus presents the virtue of poverty and of overcoming greed, and that monks should be satisfied with "small possessions of utter need, knowing that greed is a leprosy for monks". Columbanus also instructs that "nakedness and disdain of riches are the first perfection of monks, but the second is the purging of vices, the third the most perfect and perpetual love of God and unceasing affection for things divine, which follows on the forgetfulness of earthly things. Since this is so, we have need of few things, according to the word of the Lord, or even of one." In the fifth chapter, Columbanus warns against vanity, reminding the monks of Jesus' warning in Luke 16:15: "You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of others, but God knows your hearts. What people value highly is detestable in God's sight." In the sixth chapter, Columbanus instructs that "a monk's chastity is indeed judged in his thoughts" and warns, "What profit is it if he be virgin in body, if he be not virgin in mind? For God, being Spirit."

In the seventh chapter, Columbanus instituted a service of perpetual prayer, known as ''

Historian Alexander O'Hara states that Columbanus had a "very strong sense of Irish identity...He’s the first person to write about Irish identity, he’s the first Irish person that we have a body of literary work from, so even on that point of view he’s very important in terms of Irish identity." In 1950 a congress celebrating the 1,400th anniversary of his birth took place in

Historian Alexander O'Hara states that Columbanus had a "very strong sense of Irish identity...He’s the first person to write about Irish identity, he’s the first Irish person that we have a body of literary work from, so even on that point of view he’s very important in terms of Irish identity." In 1950 a congress celebrating the 1,400th anniversary of his birth took place in

The remains of Columbanus are preserved in the crypt at

The remains of Columbanus are preserved in the crypt at

The Life of St. Columban, by the Monk Jonas

(

The Order of the Knights of Saint Columbanus

(

Letters of Columbanus

(CELT) {{Authority control Irish writers Irish literature 6th-century Latin writers 7th-century Latin writers 543 births 615 deaths Irish Christian missionaries Founders of Catholic religious communities 7th-century Christian saints Burials at Bobbio Abbey Medieval Irish saints 6th-century Irish abbots 7th-century Irish priests People from County Meath Irish expatriates in France Irish expatriates in Italy Medieval Irish saints on the Continent Medieval Irish writers Founders of Christian monasteries 7th-century Irish writers 6th-century Irish writers Irish Latinists Missionary linguists

Irish missionary

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaelic missionaries originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales, England and Merovingian France. Celtic Christianity sprea ...

notable for founding a number of monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

after 590 in the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey

Luxeuil Abbey (), the ''Abbaye Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul'', was one of the oldest and best-known monasteries in Burgundy, located in what is now the département of Haute-Saône in Franche-Comté, France.

History Columbanus

It was founded circa 5 ...

in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di San Colombano'') is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. I ...

in present-day Italy.

Columbanus taught an Irish monastic rule and penitential practices for those repenting of sins, which emphasised private confession to a priest, followed by penances levied by the priest in reparation for the sins. Columbanus is one of the earliest identifiable Hiberno-Latin

Hiberno-Latin, also called Hisperic Latin, was a learned style of literary Latin first used and subsequently spread by Irish monks during the period from the sixth century to the tenth century.

Vocabulary and influence

Hiberno-Latin was notab ...

writers.

Sources

Most of what we know about Columbanus is based on Columbanus' own works (as far as they have been preserved) and Jonas of Susa's ''Vita Columbani'' (''Life of Columbanus''), which was written between 639 and 641. Jonas entered Bobbio after Columbanus' death but relied on reports of monks who still knew Columbanus. A description of miracles of Columbanus written by an anonymous monk of Bobbio is of much later date.O'Hara, Alexander, and Faye Taylor. "Aristocratic and Monastic Conflict in Tenth-Century Italy: the Case of Bobbio and the ''Miracula Sancti Columbani''" in ''Viator. Medieval and Renaissance Studies''. 44:3 (2013), pp. 43–61. In the second volume of his ''Acta Sanctorum O.S.B.'', Mabillon gives the life in full, together with an appendix on the miracles of Columbanus, written by an anonymous member of the Bobbio community.Biography

Early life

Columbanus (the Latinised form of ''Columbán'', meaning ''the white dove'') was born inLeinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

, Ireland in 543. After his conception, his mother was said to have had a vision of her child's "remarkable genius".

He was first educated under Abbot Sinell of Cluaninis, whose monastery was on an island of the River Erne

The River Erne ( , ga, Abhainn na hÉirne or ''An Éirne'') in the northwest of the island of Ireland, is the second-longest river in Ulster, flowing through Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and forming part of their border.

...

, in modern County Fermanagh

County Fermanagh ( ; ) is one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the six counties of Northern Ireland.

The county covers an area of 1,691 km2 (653 sq mi) and has a population of 61,805 a ...

. Under Sinell's instruction, Columbanus composed a commentary on the Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

.

Columbanus then moved to Bangor Abbey

Bangor Abbey was established by Saint Comgall in 558 in Bangor, County Down, Northern Ireland and was famous for its learning and austere rule. It is not to be confused with the slightly older abbey in Wales on the site of Bangor Cathedral.

His ...

where he studied to become a teacher of the Bible. He was well-educated in the areas of grammar, rhetoric, geometry, and the Holy Scriptures. Abbot Comgall

Saint Comgall (c. 510–520 – 597/602), an early Irish saint, was the founder and abbot of the great Irish monastery at Bangor in Ireland.

MacCaffrey,James (1908). " St. Comgall". In ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Co ...

taught him Greek and Latin. He stayed at Bangor until c. 590, when Comgall reluctantly gave him permission to travel to the continent.Wallace 1995, p. 43.

Frankish Gaul (c. 590 – 610)

Columbanus set sail with twelve companions: Attala, Columbanus the Younger, Gallus, Domgal, Cummain, Eogain, Eunan, Gurgano, Libran, Lua, Sigisbert and Waldoleno. They crossed thechannel

Channel, channels, channeling, etc., may refer to:

Geography

* Channel (geography), in physical geography, a landform consisting of the outline (banks) of the path of a narrow body of water.

Australia

* Channel Country, region of outback Austral ...

via Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

and landed in Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

, Brittany.

Columbanus then entered Burgundian France. Jonas writes that:At that time, either because of the numerous enemies from without, or on account of the carelessness of the bishops, the Christian faith had almost departed from that country. The creed alone remained. But the saving grace of penance and the longing to root out the lusts of the flesh were to be found only in a few. Everywhere that he went the noble man olumbanuspreached the Gospel. And it pleased the people because his teaching was adorned by eloquence and enforced by examples of virtue.Columbanus and his companions were welcomed by King Guntram of Burgundy, who granted them land at Anegray, where they converted a ruined Roman fortress into a school. Despite its remote location in the

Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

, the school rapidly attracted so many students that they moved to a new site at Luxeuil

Luxeuil-les-Bains () is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

History

Luxeuil (sometimes rendered Luxeu in older texts) was the Roman Luxovium and contained many fine buildings at ...

and then established a second school at Fontaines. These schools remained under Columbanus' authority, and their rules of life reflected the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

tradition in which he had been educated.

As these communities expanded and drew more pilgrims, Columbanus sought greater solitude. Often he would withdraw to a cave seven miles away, with a single companion who acted as messenger between himself and his companions.

Conflict with Frankish bishops

Tensions arose in 603 CE when St. Columbanus and his followers argued with Frankish bishops over the exact date of Easter. (St. Columbanus celebrated Easter according to Celtic rites and the Celtic Christian calendar.) The Frankish bishops may have feared his growing influence. During the first half of the sixth century, the councils of Gaul had given to bishops absolute authority over religious communities. Celtic Christians, Columbanus and his monks used the Irish Easter calculation, a version ofBishop Augustalis Augustalis ('' fl.'' 5th century) was the first bishop of Toulon, according to some authorities. He was appointed in 441. He attended the Council of Orange that year, and the Council of Vaison the following. He is associated with the '' civitas'' o ...

's 84-year ''computus

As a moveable feast, the date of Easter is determined in each year through a calculation known as (). Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the Paschal full moon, which is the first full moon on or after 21 March (a fixed approxi ...

'' for determining the date of Easter (Quartodecimanism

Quartodecimanism (from the Vulgate Latin ''quarta decima'' in Leviticus 23:5, meaning fourteenth) is the practice of celebrating Easter on the 14th of Nisan being on whatever day of the week, practicing Easter around the same time as the Passover ...

), whereas the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

had adopted the Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

cycle of 532 years. The bishops objected to the newcomers' continued observance of their own dating, which — among other issues — caused the end of Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

to differ. They also complained about the distinct Irish tonsure.

In 602, the bishops assembled to judge Columbanus, but he did not appear before them as requested. Instead, he sent a letter to the prelates — a strange mixture of freedom, reverence, and charity — admonishing them to hold synods more frequently, and advising them to pay more attention to matters of equal importance to that of the date of Easter. In defence of his following his traditional paschal cycle, he wrote:

When the bishops refused to abandon the matter, Columbanus appealed directly to Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

. In the third and only surviving letter, he asks "the holy Pope, his Father" to provide "the strong support of his authority" and to render a "verdict of his favour", apologising for "presuming to argue as it were, with him who sits in the chair of Peter, Apostle and Bearer of the Keys". None of the letters were answered, most likely due to the pope's death in 604.

Columbanus then sent a letter to Gregory's successor, Pope Boniface IV

Pope Boniface IV ( la, Bonifatius IV; 550 – 8 May 615) was the bishop of Rome from 608 to his death. Boniface had served as a deacon under Pope Gregory I, and like his mentor, he ran the Lateran Palace as a monastery. As pope, he encouraged m ...

, asking him to confirm the tradition of his elders — if it is not contrary to the Faith — so that he and his monks could follow the rites of their ancestors. Before Boniface responded, Columbanus moved outside the jurisdiction of the Frankish bishops. As the Easter issue appears to end around that time, Columbanus may have stopped celebrating Irish date of Easter after moving to Italy.

Conflict with Brunhilda of Austrasia

Columbanus was also involved in a dispute with members of the Burgundian dynasty. Upon the death of King Guntram of Burgundy, the succession passed to his nephew,Childebert II

Childebert II (c.570–596) was the Merovingian king of Austrasia (which included Provence at the time) from 575 until his death in March 596, as the only son of Sigebert I and Brunhilda of Austrasia; and the king of Burgundy from 592 to his de ...

, the son of his brother Sigebert Sigebert (which means roughly "magnificent victory"), also spelled Sigibert, Sigobert, Sigeberht, or Siegeberht, is the name of:

Frankish and Anglo-Saxon kings

* Sigobert the Lame (died c. 509), a king of the Franks

* Sigebert I, King of Austrasi ...

and Sigebert's wife Brunhilda of Austrasia

Brunhilda (c. 543–613) was queen consort of Austrasia, part of Francia, by marriage to the Merovingian king Sigebert I of Austrasia, and regent for her son, grandson and great-grandson.

In her long and complicated career she ruled the eastern ...

. When Childebert II died, his territories were divided between his two sons: Theuderic II

Theuderic II (also spelled Theuderich, Theoderic or Theodoric; in French, ''Thierry'') (587–613), king of Burgundy (595–613) and Austrasia (612–613), was the second son of Childebert II. At his father's death in 595, he received Guntram's k ...

inherited the Kingdom of Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

and Theudebert II

Theudebert II () (c.585-612), King of Austrasia (595–612 AD), was the son and heir of Childebert II. He received the kingdom of Austrasia plus the cities (''civitates'') of Poitiers, Tours, Le Puy-en-Velay, Bordeaux, and Châteaudun, as well as ...

inherited the Kingdom of Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

. Both were minors and Brunhilda, their grandmother, ruled as their regents.

Theuderic II "very often visited" Columbanus, but when Columbanus rebuked him for having a concubine, Brunhilda became his bitterest foe because she feared the loss of her influence if Theuderic II married.Cusack 2002, p. 173. Brunhilda incited the court and Catholic bishops against Columbanus and Theuderic II confronted Columbanus at Luxeuil, accusing him of violating the "common customs" and "not allowing all Christians" in the monastery. Columbanus asserted his independence to run the monastery without interference and was imprisoned at Besançon

Besançon (, , , ; archaic german: Bisanz; la, Vesontio) is the prefecture of the department of Doubs in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. The city is located in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerl ...

for execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

.

Columbanus escaped and returned to Luxeuil. When the king and his grandmother found out, they sent soldiers to drive him back to Ireland by force, separating him from his monks by insisting that only those from Ireland could accompany him into exile.

Columbanus was taken to Nevers

Nevers ( , ; la, Noviodunum, later ''Nevirnum'' and ''Nebirnum'') is the prefecture of the Nièvre Departments of France, department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Regions of France, region in central France. It was the principal city of the ...

, then travelled by boat down the Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône ...

river to the coast. At Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

he visited the tomb of Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

, and sent a message to Theuderic II indicating that within three years he and his children would perish. When he arrived at Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

, he wrote a letter before embarkation to his fellow monks at Luxeuil monastery. The letter urged his brethren to obey Attala, who stayed behind as abbot of the monastic community.

The letter concludes:

Soon after the ship set sail from Nantes, a severe storm drove the vessel back ashore. Convinced that his holy passenger caused the tempest, the captain refused further attempts to transport the monk. Columbanus found sanctuary with Chlothar II

Chlothar II, sometime called "the Young" (French language, French: le Jeune), (May/June 584 – 18 October 629), was king of Neustria and king of the Franks, and the son of Chilperic I and his third wife, Fredegund. He started his reign as an in ...

of Neustria

Neustria was the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks.

Neustria included the land between the Loire and the Silva Carbonaria, approximately the north of present-day France, with Paris, Orléans, Tours, Soissons as its main cities. It later ...

at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

, who gave him an escort to the court of King Theudebert II

Theudebert II () (c.585-612), King of Austrasia (595–612 AD), was the son and heir of Childebert II. He received the kingdom of Austrasia plus the cities (''civitates'') of Poitiers, Tours, Le Puy-en-Velay, Bordeaux, and Châteaudun, as well as ...

of Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

.

The Alps (611-612)

Columbanus arrived at Theudebert II's court inMetz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand E ...

in 611, where members of the Luxeuil school met him and Theudebert II granted them land at Bregenz

Bregenz (; gsw, label= Vorarlbergian, Breagaz ) is the capital of Vorarlberg, the westernmost state of Austria. The city lies on the east and southeast shores of Lake Constance, the third-largest freshwater lake in Central Europe, between Switze ...

. They travelled up the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

via Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

to the lands of the Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

and Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

in the northern Alps, intending to preach the Gospel to these people. He followed the Rhine river and its tributaries, the Aar

AAR or Aar may refer to:

Geography

* Aar, a river in Switzerland, tributary of the Rhine

*Aar (Lahn), a tributary of Lahn river in Germany, descending from the Taunus mountains

* Aar (Dill), a tributary of Dill river in Germany, also in the bas ...

and the Limmat

The Limmat is a river in Switzerland. The river commences at the outfall of Lake Zurich, in the southern part of the city of Zurich. From Zurich it flows in a northwesterly direction, after 35 km reaching the river Aare. The confluenc ...

, and then on to Lake Zurich

__NOTOC__

Lake Zurich ( Swiss German/Alemannic: ''Zürisee''; German: ''Zürichsee''; rm, Lai da Turitg) is a lake in Switzerland, extending southeast of the city of Zürich. Depending on the context, Lake Zurich or ''Zürichsee'' can be used to ...

. Columbanus chose the village of Tuggen

Tuggen is a municipality in March District in the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland.

History

According to Walafrid Strabo the Irish missionaries Columban and Gall arrived at Tuggen around the year 610. They intended to settle in the area, but fled ...

as his initial community, but the work was not successful. He continued north-east by way of Arbon to Bregenz

Bregenz (; gsw, label= Vorarlbergian, Breagaz ) is the capital of Vorarlberg, the westernmost state of Austria. The city lies on the east and southeast shores of Lake Constance, the third-largest freshwater lake in Central Europe, between Switze ...

on Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

. Here he found an oratory dedicated to Aurelia of Strasbourg

Saint Aurelia of Strasbourg was a 4th-century saint, whose tomb in Strasbourg became the centre of a popular cult in the Middle Ages.

Biography

According to the legend, Aurelia accompanied Saint Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins from Roman Br ...

containing three brass images of their tutelary deities. Columbanus commanded Gallus, who knew the local language, to preach to the inhabitants, and many were converted. The three brass images were destroyed, and Columbanus blessed the little church, placing the relics of Aurelia beneath the altar. A monastery was erected, Mehrerau Abbey

Wettingen-Mehrerau Abbey is a Cistercian territorial abbey and cathedral located at Mehrerau on the outskirts of Bregenz in Vorarlberg, Austria. Wettingen-Mehrerau Abbey is directly subordinate to the Holy See and thus forms no part of the Catho ...

, and the brethren observed their regular life. Columbanus stayed in Bregenz for about one year.

In the spring of 612, war broke out between Austrasia and Burgundy and Theudebert II was resoundingly beaten by Theuderic II. Austrasia was subsumed under the kingdom of Burgundy and Columbanus was again vulnerable to Theuderic II's opprobrium. When Columbanus' students began to be murdered in the woods, Columbanus decided to cross the Alps into Lombardy.

Gallus remained in this area until his death in 646. About seventy years later at the place of Gallus' cell the Abbey of Saint Gall

The Abbey of Saint Gall (german: Abtei St. Gallen) is a dissolved abbey (747–1805) in a Catholic religious complex in the city of St. Gallen in Switzerland. The Carolingian-era monastery existed from 719, founded by Saint Othmar on the spot w ...

was founded. The city of St. Gallen

, neighboring_municipalities = Eggersriet, Gaiserwald, Gossau, Herisau (AR), Mörschwil, Speicher (AR), Stein (AR), Teufen (AR), Untereggen, Wittenbach

, twintowns = Liberec (Czech Republic)

, website ...

originated as an adjoining settlement of the abbey.

Lombardy (612-615)

Columbanus arrived inMilan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

in 612 and was welcomed by King Agilulf

Agilulf ( 555 – April 616), called ''the Thuringian'' and nicknamed ''Ago'', was a duke of Turin and king of the Lombards from 591 until his death.

A relative of his predecessor Authari, Agilulf was of Thuringian origin and belonged to the An ...

and Queen Theodelinda

Theodelinda also spelled ''Theudelinde'' ( 570–628 AD), was a queen of the Lombards by marriage to two consecutive Lombard rulers, Autari and then Agilulf, and regent of Lombardia during the minority of her son Adaloald, and co-regent when he ...

of the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

. He immediately began refuting the teachings of Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

, which had enjoyed a degree of acceptance in Italy. He wrote a treatise against Arianism, which has since been lost. In 614, Agilulf granted Columbanus land for a school at the site of a ruined church at Bobbio

Bobbio ( Bobbiese: ; lij, Bêubbi; la, Bobium) is a small town and commune in the province of Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy. It is located in the Trebbia River valley southwest of the town Piacenza. There is also an abbey and a dioc ...

.

At the king's request, Columbanus wrote a letter to Pope Boniface IV

Pope Boniface IV ( la, Bonifatius IV; 550 – 8 May 615) was the bishop of Rome from 608 to his death. Boniface had served as a deacon under Pope Gregory I, and like his mentor, he ran the Lateran Palace as a monastery. As pope, he encouraged m ...

on the controversy over the ''Three Chapters

The Three-Chapter Controversy, a phase in the Chalcedonian controversy, was an attempt to reconcile the non-Chalcedonians of Syriac Orthodox Church, Syria and Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Egypt with Chalcedonian Christianity, following t ...

''—writings by Syrian bishops suspected of Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

, which had been condemned in the fifth century as heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

had tolerated in Lombardy those persons who defended the ''Three Letters'', among them King Agilulf. Columbanus agreed to take up the issue on behalf of the king. The letter has a diplomatic tone and begins with an apology that a "foolish Scot (''Scottus'', Irishman)" would be writing for a Lombard king. After acquainting the pope with the imputations brought against him, he entreats the pontiff to prove his orthodoxy and assemble a council. When critiquing Boniface, he writes that his freedom of speech is consistent with the custom of his country. Some of the language used in the letter might now be regarded as disrespectful, but in that time, faith and austerity could be more indulgent.Montalembert 1861, p. 440. Columbanus was tactful when making critiques, as he begins the letter expresses with the most affectionate and impassioned devotion to the Holy See.

Later, he reveals charges against the Papacy so as to encourage Boniface to make concessions:

Columbanus' deference towards Rome is sufficiently clear, calling the pope "his Lord and Father in Christ", the "Chosen Watchman", and the "First Pastor, set higher than all mortals".Allnatt 2007, p. 105. At the same time, he abrogated Petrine succession for his own churches, asserting "we Irish, inhabitants of the world’s edge, are disciples of Saints Peter and Paul and of all the disciples" and that "the unity of faith has produced in the whole world a unity of power and privilege."

King Agilulf gave Columbanus a tract of land called

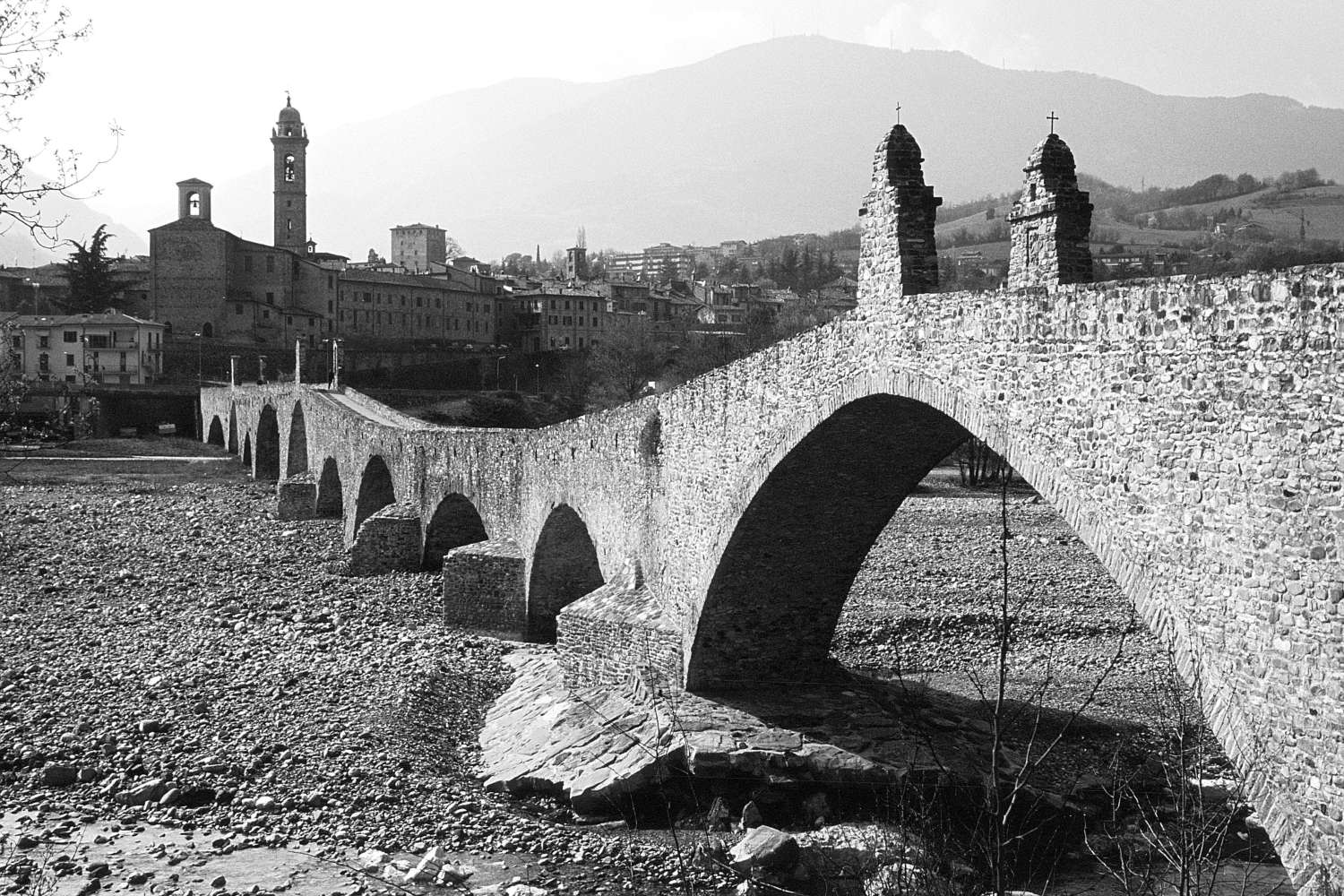

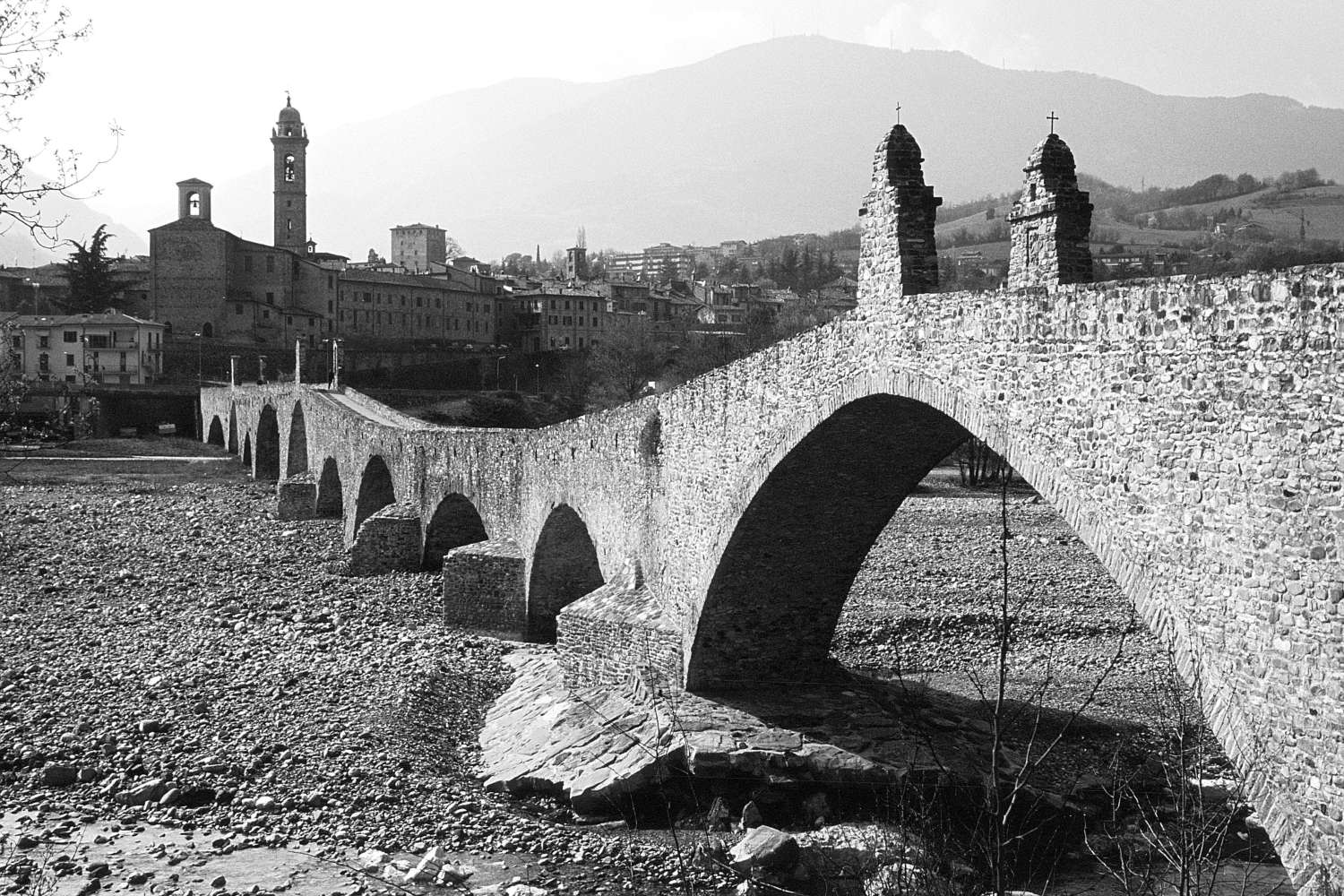

King Agilulf gave Columbanus a tract of land called Bobbio

Bobbio ( Bobbiese: ; lij, Bêubbi; la, Bobium) is a small town and commune in the province of Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy. It is located in the Trebbia River valley southwest of the town Piacenza. There is also an abbey and a dioc ...

between Milan and Genoa near the Trebbia

The Trebbia (stressed ''Trèbbia''; la, Trebia) is a river predominantly of Liguria and Emilia Romagna in northern Italy. It is one of the four main right-bank tributaries of the river Po (river), Po, the other three being the Tanaro River, Tanar ...

river, situated in a defile of the Apennine Mountains

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

, to be used as a base for the conversion of the Lombard people. The area contained a ruined church and wastelands known as ''Ebovium'', which had formed part of the lands of the papacy prior to the Lombard invasion. Columbanus wanted this secluded place, for while enthusiastic in the instruction of the Lombards he preferred solitude for his monks and himself. Next to the little church, which was dedicated to Peter the Apostle

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupatio ...

, Columbanus erected a monastery in 614. Bobbio Abbey

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di San Colombano'') is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. I ...

at its foundation followed the Rule of Saint Columbanus, based on the monastic practices of Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

. For centuries it remained the stronghold of orthodoxy in northern Italy.

Death

During the last year of his life, Columbanus received messenges from King

During the last year of his life, Columbanus received messenges from King Chlothar II

Chlothar II, sometime called "the Young" (French language, French: le Jeune), (May/June 584 – 18 October 629), was king of Neustria and king of the Franks, and the son of Chilperic I and his third wife, Fredegund. He started his reign as an in ...

, inviting him to return to Burgundy, now that his enemies were dead. Columbanus did not return, but requested that the king should always protect his monks at Luxeuil Abbey

Luxeuil Abbey (), the ''Abbaye Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul'', was one of the oldest and best-known monasteries in Burgundy, located in what is now the département of Haute-Saône in Franche-Comté, France.

History Columbanus

It was founded circa 5 ...

. He prepared for death by retiring to his cave on the mountainside overlooking the Trebbia river, where, according to a tradition, he had dedicated an oratory to Our Lady.Montalembert 1861, p. 444. Columbanus died at Bobbio on 21 November 615 and is buried there.

Rule of Saint Columbanus

The Rule of Saint Columbanus embodied the customs ofBangor Abbey

Bangor Abbey was established by Saint Comgall in 558 in Bangor, County Down, Northern Ireland and was famous for its learning and austere rule. It is not to be confused with the slightly older abbey in Wales on the site of Bangor Cathedral.

His ...

and other Irish monasteries. Much shorter than the Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

, the Rule of Saint Columbanus consists of ten chapters, on the subjects of obedience, silence, food, poverty, humility, chastity, choir offices, discretion, mortification, and perfection.

In the first chapter, Columbanus introduces the great principle of his Rule: obedience, absolute and unreserved. The words of seniors should always be obeyed, just as "Christ obeyed the Father up to death for us." One manifestation of this obedience was constant hard labour designed to subdue the flesh, exercise the will in daily self-denial, and set an example of industry in cultivation of the soil. The least deviation from the Rule entailed corporal punishment, or a severe form of fasting.Smith 2012, p. 201. In the second chapter, Columbanus instructs that the rule of silence be "carefully observed", since it is written: "But the nurture of righteousness is silence and peace". He also warns, "Justly will they be damned who would not say just things when they could, but preferred to say with garrulous loquacity what is evil ..." In the third chapter, Columbanus instructs, "Let the monks' food be poor and taken in the evening, such as to avoid repletion, and their drink such as to avoid intoxication, so that it may both maintain life and not harm ..." Columbanus continues:

In the fourth chapter, Columbanus presents the virtue of poverty and of overcoming greed, and that monks should be satisfied with "small possessions of utter need, knowing that greed is a leprosy for monks". Columbanus also instructs that "nakedness and disdain of riches are the first perfection of monks, but the second is the purging of vices, the third the most perfect and perpetual love of God and unceasing affection for things divine, which follows on the forgetfulness of earthly things. Since this is so, we have need of few things, according to the word of the Lord, or even of one." In the fifth chapter, Columbanus warns against vanity, reminding the monks of Jesus' warning in Luke 16:15: "You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of others, but God knows your hearts. What people value highly is detestable in God's sight." In the sixth chapter, Columbanus instructs that "a monk's chastity is indeed judged in his thoughts" and warns, "What profit is it if he be virgin in body, if he be not virgin in mind? For God, being Spirit."

In the seventh chapter, Columbanus instituted a service of perpetual prayer, known as ''

In the fourth chapter, Columbanus presents the virtue of poverty and of overcoming greed, and that monks should be satisfied with "small possessions of utter need, knowing that greed is a leprosy for monks". Columbanus also instructs that "nakedness and disdain of riches are the first perfection of monks, but the second is the purging of vices, the third the most perfect and perpetual love of God and unceasing affection for things divine, which follows on the forgetfulness of earthly things. Since this is so, we have need of few things, according to the word of the Lord, or even of one." In the fifth chapter, Columbanus warns against vanity, reminding the monks of Jesus' warning in Luke 16:15: "You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of others, but God knows your hearts. What people value highly is detestable in God's sight." In the sixth chapter, Columbanus instructs that "a monk's chastity is indeed judged in his thoughts" and warns, "What profit is it if he be virgin in body, if he be not virgin in mind? For God, being Spirit."

In the seventh chapter, Columbanus instituted a service of perpetual prayer, known as ''laus perennis

Perpetual prayer (Latin: ''laus perennis'') is the Christian practice of continuous prayer carried out by a group.

History

The practice of perpetual prayer was inaugurated by the archimandrite Alexander (died about 430), the founder of the monasti ...

'', by which choir succeeded choir, both day and night.Montalembert 1898, II p. 405. In the eighth chapter, Columbanus stresses the importance of discretion in the lives of monks to avoid "the downfall of some, who beginning without discretion and passing their time without a sobering knowledge, have been unable to complete a praiseworthy life." Monks are instructed to pray to God for to "illumine this way, surrounded on every side by the world's thickest darkness". Columbanus continues:

In the ninth chapter, Columbanus presents mortification as an essential element in the lives of monks, who are instructed, "Do nothing without counsel." Monks are warned to "beware of a proud independence, and learn true lowliness as they obey without murmuring and hesitation." According to the Rule, there are three components to mortification: "not to disagree in mind, not to speak as one pleases with the tongue, not to go anywhere with complete freedom." This mirrors the words of Jesus, "For I have come down from heaven not to do my will but to do the will of him who sent me." (John 6:38) In the tenth and final chapter, Columbanus regulates forms of penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

(often corporal) for offences, and it is here that the Rule of Saint Columbanus differs significantly from that of Saint Benedict.

The Communal Rule of Columbanus required monks to fast every day until ''None

None may refer to:

*Zero, the mathematical concept of the quantity "none"

*Empty set, the mathematical concept of the collection of things represented by "none"

*''none'', an indefinite pronoun in the English language

Music

* ''None'' (Meshuggah E ...

'' or 3 p.m., this was later relaxed and observed on designated days.Frantzen, Allen J. (2014). ''Food, Eating and Identity in Early Medieval England''. The Boydell Press. p. 184. Columbanus' Rule regarding diet was very strict. Monks were to eat a limited diet of beans, vegetables, flour mixed with water and small bread of a loaf, taken in the evenings.

The habit of the monks consisted of a tunic of undyed wool, over which was worn the cuculla

A cowl is an item of clothing consisting of a long, hooded garment with wide sleeves, often worn by monks.

Originally it may have referred simply to the hooded portion of a cloak. In contemporary usage, however, it is distinguished from a clo ...

, or cowl, of the same material. A great deal of time was devoted to various kinds of manual labour, not unlike the life in monasteries of other rules. The Rule of Saint Columbanus was approved of by the Fourth Council of Mâcon

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

in 627, but it was superseded at the close of the century by the Rule of Saint Benedict. For several centuries in some of the greater monasteries the two rules were observed conjointly.

Character

Columbanus did not lead a perfect life. According to Jonas and other sources, he could be impetuous and even headstrong, for by nature he was eager, passionate, and dauntless. These qualities were both the source of his power and the cause of his mistakes. His virtues, however, were quite remarkable. Like many saints, he had a great love for God's creatures. Stories claim that as he walked in the woods, it was not uncommon for birds to land on his shoulders to be caressed, or forsquirrel

Squirrels are members of the family Sciuridae, a family that includes small or medium-size rodents. The squirrel family includes tree squirrels, ground squirrels (including chipmunks and prairie dogs, among others), and flying squirrels. Squ ...

s to run down from the trees and nestle in the folds of his cowl. Although a strong defender of Irish traditions, he never wavered in showing deep respect for the Holy See as the supreme authority. His influence in Europe was due to the conversions he effected and to the rule that he composed. It may be that the example and success of Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

in Caledonia inspired him to similar exertions. The life of Columbanus stands as the prototype of missionary activity in Europe, followed by such men as Kilian

Killian or Kilian, as a given name, is an Anglicized version of the Irish name Cillian. The name Cillian was borne by several early Irish saints including missionaries to Artois and Franconia and the author of the life of St Brigid.

The name is ...

, Vergilius of Salzburg

Virgil (– 27 November 784), also spelled Vergil, Vergilius, Virgilius, Feirgil or Fearghal, was an Irish people, Irish churchman and early astronomer. He left Ireland around 745, intending to visit the Holy Land; but, like many of his countrym ...

, Donatus of Fiesole

Donatus of Fiesole (died 876) was an Irish teacher and poet, and Bishop of Fiesole.

Biography

Donatus was born in Ireland to noble parents towards the end of the eighth century. Despite there being little biographical detail in the tenth/el ...

, Wilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and ...

, Willibrord

Willibrord (; 658 – 7 November AD 739) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary and saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands. He became the first bishop of Utrecht and died at Echternach, Luxembourg.

Early life

His fathe ...

, Suitbert of Kaiserwerdt

Saint Suitbert, Suidbert, Suitbertus, Swithbert, or Swidbert was born in Northumbria, England, in the seventh century, and accompanied Willibrord on the Anglo-Saxon mission.

Life

Suitbert was born in Northumbria. According to legend, his mother ...

, Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of ...

, and Ursicinus of Saint-Ursanne

Ursicinus (also ''Hursannus, Ursitz, Oschanne'', fl. 620) was an Irish missionary and hermit in the Jura region.

Information

A ''vita'' of his is preserved in a redaction of the 11th century. According to this account, he was a disciple of ...

.

Miracles

The following are the principal miracles attributed to his intercession: # Procuring food for a sick monk and curing the wife of his benefactor # Escaping injury while surrounded by wolves # Causing a bear to evacuate a cave at his biddings # Producing a spring of water near his cave # Replenishing the Luxeuil granary # Multiplying bread and beer for his community # Curing sick monks, who rose from their beds at his request to reap the harvest # Giving sight to a blind man at Orleans # Destroying with his breath a cauldron of beer prepared for a pagan festival # Taming a bear and yoking it to a plough Jonas relates the occurrence of a miracle during Columbanus' time in Bregenz, when that region was experiencing a period of severe famine.Legacy

Historian Alexander O'Hara states that Columbanus had a "very strong sense of Irish identity...He’s the first person to write about Irish identity, he’s the first Irish person that we have a body of literary work from, so even on that point of view he’s very important in terms of Irish identity." In 1950 a congress celebrating the 1,400th anniversary of his birth took place in

Historian Alexander O'Hara states that Columbanus had a "very strong sense of Irish identity...He’s the first person to write about Irish identity, he’s the first Irish person that we have a body of literary work from, so even on that point of view he’s very important in terms of Irish identity." In 1950 a congress celebrating the 1,400th anniversary of his birth took place in Luxeuil

Luxeuil-les-Bains () is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

History

Luxeuil (sometimes rendered Luxeu in older texts) was the Roman Luxovium and contained many fine buildings at ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. It was attended by Robert Schuman

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Robert Schuman (; 29 June 18864 September 1963) was a Luxembourg-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat (Popular Republican Movement) political thinker and activist. Twice Prime Minister of France, a ref ...

, Seán MacBride

Seán MacBride (26 January 1904 – 15 January 1988) was an Irish Clann na Poblachta politician who served as Minister for External Affairs from 1948 to 1951, Leader of Clann na Poblachta from 1946 to 1965 and Chief of Staff of the IRA from 193 ...

, the future Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

, and John A. Costello

John Aloysius Costello (20 June 1891 – 5 January 1976) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 1948 to 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, Leader of the Opposition from 1951 to 1954 and from 1957 to 1959, and Attorney General of ...

who said "All statesmen of today might well turn their thoughts to St Columban and his teaching. History records that it was by men like him that civilisation was saved in the 6th century."

Columbanus is also remembered as the first Irish person to be the subject of a biography. An Italian monk named Jonas of Bobbio

Jonas of Bobbio (also known as Jonas of Susa) (Sigusia, now Susa, Italy, 600 – after 659 AD) was a Columbanian monk and a major Latin monastic author of hagiography. His ''Life of Saint Columbanus'' is "one of the most influential works o ...

wrote a biography of him some twenty years after Columbanus’ death. His use of the phrase in 600 AD ''totius Europae'' (all of Europe) in a letter to Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregoria ...

is the first known use of the expression.

At Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

in Brittany, there is a granite cross bearing Columbanus's name to which people once came to pray for rain in times of drought. The nearby village of Saint-Coulomb

Saint-Coulomb (; br, Sant-Kouloum) is a commune in the Ille-et-Vilaine department in Brittany in northwestern France.

Population

Inhabitants are called ''colombanais'' in French.

History

Its name comes from Saint Colomban, who came in the ye ...

commemorates him in name.

In France, the ruins of Columbanus' first monastery at Annegray are legally protected through the efforts of the Association Internationale des Amis de St Columban, which purchased the site in 1959. The association also owns and protects the site containing the cave, which served as Columbanus' cell, and the holy well that he created nearby. At Luxeuil-les-Bains

Luxeuil-les-Bains () is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

History

Luxeuil (sometimes rendered Luxeu in older texts) was the Roman Luxovium and contained many fine buildings at ...

, the Basilica of Saint Peter stands on the site of Columbanus' first church. A statue near the entrance, unveiled in 1947, shows him denouncing the immoral life of King Theuderic II

Theuderic II (also spelled Theuderich, Theoderic or Theodoric; in French, ''Thierry'') (587–613), king of Burgundy (595–613) and Austrasia (612–613), was the second son of Childebert II. At his father's death in 595, he received Guntram's k ...

. Formally an abbey church, the basilica contains old monastic buildings, which have been used as a minor seminary since the nineteenth century. It is dedicated to Columbanus and houses a bronze statue of him in its courtyard.

If Bobbio Abbey

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di San Colombano'') is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. I ...

in Italy became a citadel of faith and learning, Luxeuil Abbey

Luxeuil Abbey (), the ''Abbaye Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul'', was one of the oldest and best-known monasteries in Burgundy, located in what is now the département of Haute-Saône in Franche-Comté, France.

History Columbanus

It was founded circa 5 ...

in France became the "nursery of saints and apostles". The monastery produced sixty-three apostles who carried his rule, together with the Gospel, into France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.Stokes, p. 254. These disciples of Columbanus are credited with founding more than a hundred different monasteries.Stokes, p. 74. The canton and town still bearing the name of St. Gallen

, neighboring_municipalities = Eggersriet, Gaiserwald, Gossau, Herisau (AR), Mörschwil, Speicher (AR), Stein (AR), Teufen (AR), Untereggen, Wittenbach

, twintowns = Liberec (Czech Republic)

, website ...

testify to how well one of his disciples succeeded.

Bobbio Abbey, the latter of which became a renowned center of learning in the Early Middle Ages. (Bobbio Abbey became so famous that it rivaled the monastic community at Monte Cassino in wealth and prestige.) St. Attala continued St. Columbanus' work at Bobbio, proselytizing and collecting religious texts for the abbey's library. In Lombardy, San Colombano al Lambro

San Colombano al Lambro ( Lodigiano: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Milan in the Italian region Lombardy, located about southeast of Milan.

San Colombano al Lambro borders the following municipalities: Borghetto Lo ...

in Milan, San Colombano Belmonte

San Colombano Belmonte is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Turin in the Italian region Piedmont, located about north of Turin.

San Colombano Belmonte borders the following municipalities: Cuorgnè

Cuorgnè (; pms, Corgn� ...

in Turin, and San Colombano Certénoli

San Colombano Certenoli ( lij, San Comban) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about east of Genoa. It is the largest municipality in the Val Fontanabuona.

San Colombano Certenol ...

in Genoa all take their names from the saint.

The Missionary Society of Saint Columban

The Missionary Society of St. Columban ( la, Societas Sancti Columbani pro Missionibus ad Exteros) (abbreviated as S.S.C.M.E. or SSC), commonly known as the Columbans, is a missionary Catholic society of apostolic life of Pontifical Right foun ...

, founded in 1916, and the Missionary Sisters of St. Columban

The Missionary Sisters of St. Columban (commonly referred to as the Columban Sisters, abbreviated as S.S.C.) are a religious institute of religious sisters dedicated to serve the poor and needy in the underdeveloped nations of the world. The ...

, founded in 1924, are both dedicated to Columbanus.

Veneration

The remains of Columbanus are preserved in the crypt at

The remains of Columbanus are preserved in the crypt at Bobbio Abbey

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di San Colombano'') is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. I ...

. Many miracles have been credited to his intercession. In 1482, the relics were placed in a new shrine and laid beneath the altar of the crypt. The sacristy at Bobbio possesses a portion of the skull of Columbanus, his knife, wooden cup, bell, and an ancient water vessel, formerly containing sacred relics and said to have been given to him by Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

. According to some authorities, twelve teeth of Columbanus were taken from the tomb in the fifteenth century and kept in the treasury, but these have since disappeared.Stokes, p. 183.

Columbanus is named in the Roman Martyrology

The ''Roman Martyrology'' ( la, Martyrologium Romanum) is the official martyrology of the Catholic Church. Its use is obligatory in matters regarding the Roman Rite liturgy, but dioceses, countries and religious institutes may add duly approved ...

on 23 November, which is his feast day in Ireland. His feast is observed by the Benedictines on 21 November. Columbanus is the patron saint of motorcyclists. In art, Columbanus is represented bearded bearing the monastic cowl, holding in his hand a book with an Irish satchel

A satchel is a bag with a strap, traditionally used for carrying books.Satchel

The Cambridge Dictionary. ...

, and standing in the midst of wolves. Sometimes he is depicted in the attitude of taming a bear, or with sun-beams over his head.Husenheth, p. 33.

The Cambridge Dictionary. ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * Gray, Patrick T. R., and Michael W. Herren (1994). "Columbanus and the Three Chapters Controversy" in ''Journal of Theological Studies'', NS, 45, pp. 160–170. * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Life of St. Columban, by the Monk Jonas

(

Internet Medieval Sourcebook

The Internet History Sourcebooks Project is located at the Fordham University History Department and Center for Medieval Studies. It is a web site with modern, medieval and ancient primary source documents, maps, secondary sources, bibliographies, ...

)

*

*

The Order of the Knights of Saint Columbanus

(

CELT

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

)

Letters of Columbanus

(CELT) {{Authority control Irish writers Irish literature 6th-century Latin writers 7th-century Latin writers 543 births 615 deaths Irish Christian missionaries Founders of Catholic religious communities 7th-century Christian saints Burials at Bobbio Abbey Medieval Irish saints 6th-century Irish abbots 7th-century Irish priests People from County Meath Irish expatriates in France Irish expatriates in Italy Medieval Irish saints on the Continent Medieval Irish writers Founders of Christian monasteries 7th-century Irish writers 6th-century Irish writers Irish Latinists Missionary linguists