The Colossus of Rhodes ( grc, ὁ Κολοσσὸς Ῥόδιος, ho Kolossòs Rhódios gr, Κολοσσός της Ρόδου, Kolossós tes Rhódou) was a statue of the Greek sun-god

The Colossus of Rhodes ( grc, ὁ Κολοσσὸς Ῥόδιος, ho Kolossòs Rhódios gr, Κολοσσός της Ρόδου, Kolossós tes Rhódou) was a statue of the Greek sun-god Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; grc, , , Sun; Homeric Greek: ) is the deity, god and personification of the Sun (Solar deity). His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyper ...

, erected in the city of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, on the Greek island of the same name, by Chares of Lindos in 280 BC. One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

, it was constructed to celebrate the successful defence of Rhodes city against an attack by Demetrius Poliorcetes, who had besieged it for a year with a large army and navy.

According to most contemporary descriptions, the Colossus stood approximately 70 cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding ...

s, or high – approximately the height of the modern Statue of Liberty from feet to crown – making it the tallest statue in the ancient world. It collapsed during the earthquake of 226 BC, although parts of it were preserved. In accordance with a certain oracle, the Rhodians did not build it again. John Malalas

John Malalas ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Malálas''; – 578) was a Byzantine chronicler from Antioch (now Antakya, Turkey).

Life

Malalas was of Syrian descent, and he was a native speaker of Syriac who learned how to write in Greek later ...

wrote that Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

in his reign re-erected the Colossus, but he was mistaken. According to the Suda, the Rhodians were called Colossaeans (Κολοσσαεῖς), because they erected the statue on the island.

In 653, an Arab force under Muslim general Muawiyah I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

conquered Rhodes, and according to the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before takin ...

,See also Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe Kar ...

, '' De administrando imperio'' xx–xxi. the statue was completely destroyed and the remains sold.

Since 2008, a series of as-yet-unrealized proposals to build a new Colossus at Rhodes Harbour have been announced, although the actual location of the original monument remains in dispute.

Siege of Rhodes

In the early fourth century BC, Rhodes, allied with Ptolemy I of Egypt, prevented a mass invasion staged by their common enemy,Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he ser ...

.

In 304 BC a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius (son of Antigonus) and his army abandoned the siege, leaving behind most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment left behind for 300 talents and decided to use the money to build a colossal statue of their patron god, Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; grc, , , Sun; Homeric Greek: ) is the deity, god and personification of the Sun (Solar deity). His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyper ...

. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Lindos in Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the sculptor Lysippos, had constructed a bronze statue of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

at Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Cam ...

.

Construction

Construction began in 292 BC. Ancient accounts, which differ to some degree, describe the structure as being built with iron tie bars to which brass plates were fixed to form the skin. The interior of the structure, which stood on a whitemarble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorpho ...

pedestal near the Rhodes harbour entrance, was then filled with stone blocks as construction progressed. Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbour. According to most contemporary descriptions, the statue itself was about 70 cubits, or tall. Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower may have been used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction.

Philo of Byzantium wrote in ''De septem mundi miraculis'' that Chares created the sculpture in situ by casting it in horizontal courses and then placing "...a huge mound of earth around each section as soon as it was completed, thus burying the finished work under the accumulated earth, and carrying out the casting of the next part on the level."

Modern engineers have put forward a plausible hypothesis for the statue's construction, based on the technology of the time (which was not based on the modern principles of earthquake engineering), and the accounts of Philo and Pliny, who saw and described the ruins.

The base pedestal was said to be at least in diameter, and either circular or octagonal. The feet were carved in stone and covered with thin bronze plates riveted together. Eight forged iron bars set in a radiating horizontal position formed the ankles and turned up to follow the lines of the legs while becoming progressively smaller. Individually cast curved bronze plates square with turned-in edges were joined together by rivets through holes formed during casting to form a series of rings. The lower plates were in thickness to the knee and thick from knee to abdomen, while the upper plates were thick except where additional strength was required at joints such as the shoulder, neck, etc.

Archaeologist Ursula Vedder has proposed that the sculpture was cast in large sections following traditional Greek methods and that Philo's account is "not compatible with the situation proved by archaeology in ancient Greece."

The Standing Colossus (280–226 BC)

After twelve years, in 280 BC, the statue was completed. Preserved in Greek anthologies of poetry is what is believed to be the genuine dedication text for the Colossus.Collapse (226 BC)

The statue stood for 54 years until a 226 BC earthquake caused significant damage to large portions of Rhodes, including the harbour and commercial buildings, which were destroyed. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but the Oracle of Delphi made the Rhodians fear that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it.

The statue stood for 54 years until a 226 BC earthquake caused significant damage to large portions of Rhodes, including the harbour and commercial buildings, which were destroyed. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but the Oracle of Delphi made the Rhodians fear that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it.

Fallen state (226 BC to 653 AD)

The remains lay on the ground for over 800 years, and even broken, they were so impressive that many travelled to see them. The remains were described briefly by Strabo (64 or 63 BC – c. 24 AD), in his work Geography (Book XIV, Chapter 2.5). Strabo was a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who lived inAsia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

during the transitional period of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

Strabo is best known for his work Geographica ("Geography"), which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different regions of the world known during his lifetime. Strabo states that:

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

(AD 23/24 – 79) was a Roman author, a naturalist and natural philosopher, a naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of emperor Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

. Pliny wrote the encyclopedic ''Naturalis Historia'' (Natural History), which became an editorial model for encyclopedias. The ''Naturalis Historia'' is one of the largest single works to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day and purports to cover the entire field of ancient knowledge. Pliny remarked:

Destruction of the remains (653)

In 653, an Arab force under Muslim generalMuawiyah I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

captured Rhodes, and according to the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before takin ...

, the statue was melted down and sold to a Jewish merchant of Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city ('' polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Os ...

who loaded the bronze onto 900 camels. The Arab destruction and the purported sale to a Jew possibly originated as a powerful metaphor for Nebuchadnezzar's dream of the destruction of a great statue.

The same story is recorded by Bar Hebraeus, writing in Syriac in the 13th century in Edessa (after the Arab pillage of Rhodes): "And a great number of men hauled on strong ropes which were tied around the brass Colossus which was in the city and pulled it down. And they weighed from it three thousand loads of Corinthian brass, and they sold it to a certain Jew from Emesa" (the Syrian city of Homs). Theophanes is the sole source of this account, and all other sources can be traced to him.

Rhodes has two serious earthquakes per century, owing to its location on the seismically unstable Hellenic Arc. Pausanias tells us, writing ca. 174, how the city was so devastated by an earthquake that the Sibyl oracle foretelling its destruction was considered fulfilled. This means the statue could not have survived for long if it was ever repaired. By the 4th century Rhodes was Christianized, meaning any further maintenance or rebuilding, if there ever was any before, on an ancient pagan statue is unlikely. The metal would have likely been used for coins and maybe also tools by the time of the Arab conquests, especially during other conflicts such as the Sassanian Wars. Moreover, the island was an important Byzantine strategic point well into the ninth century, so an Arabic raid is unlikely to have stripped its metal. Since Theophanes' source was Syriac, it must have had vague information about a raid and attributed the statue's demise to it, not knowing much more. For these reasons, as well as the negative perception of the Arab conquests, L. I. Conrad considers the story of the dismantling of the statue likely to be propaganda, like the destruction of the Library of Alexandria.

Posture

The harbour-straddling Colossus was a figment of

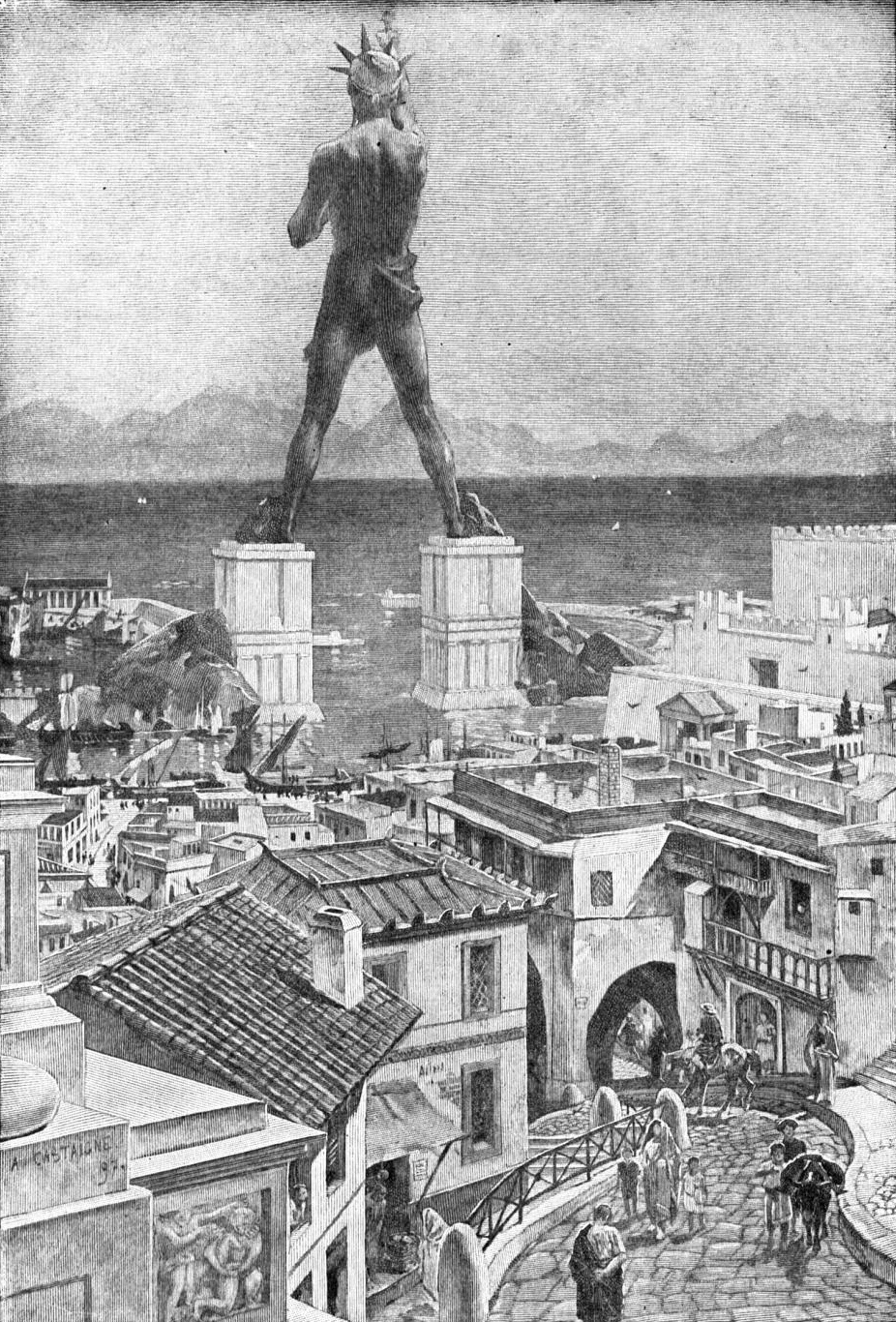

The harbour-straddling Colossus was a figment of medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

imaginations based on the dedication text's mention of "over land and sea" twice and the writings of an Italian visitor who in 1395 noted that local tradition held that the right foot had stood where the church of St John of the Colossus was then located. Many later illustrations show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbour mouth with ships passing under it. References to this conception are also found in literary works. Shakespeare's Cassius in '' Julius Caesar'' (I, ii, 136–38) says of Caesar:

Shakespeare alludes to the Colossus also in ''Troilus and Cressida

''Troilus and Cressida'' ( or ) is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1602.

At Troy during the Trojan War, Troilus and Cressida begin a love affair. Cressida is forced to leave Troy to join her father in the Greek camp. M ...

'' (V.5) and in '' Henry IV, Part 1'' (V.1).

" The New Colossus" (1883), a sonnet by Emma Lazarus written on a cast bronze plaque and mounted inside the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1903, contrasts the latter with:

While these fanciful images feed the misconception, the mechanics of the situation reveal that the Colossus could not have straddled the harbour as described in Lemprière's '' Classical Dictionary''. If the completed statue had straddled the harbour, the entire mouth of the harbour would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction, and the ancient Rhodians did not have the means to dredge and re-open the harbour after construction. Also, the fallen statue would have blocked the harbour, and since the ancient Rhodians did not have the ability to remove the fallen statue from the harbour, it would not have remained visible on land for the next 800 years, as discussed above. Even neglecting these objections, the statue was made of bronze, and engineering analyses indicate that it could not have been built with its legs apart without collapsing under its own weight. Many researchers have considered alternative positions for the statue which would have made it more feasible for actual construction by the ancients. There is also no evidence that the statue held a torch aloft; the records simply say that after completion, the Rhodians kindled the "torch of freedom". A relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

in a nearby temple shows Helios standing with one hand shielding his eyes, similar to the way a person shields their eyes when looking toward the sun, and it is quite possible that the colossus was constructed in the same pose.

While scholars do not know what the statue looked like, they do have a good idea of what the head and face looked like, as it was of a standard rendering at the time. The head would have had curly hair with evenly spaced spikes of bronze or silver flame radiating, similar to the images found on contemporary Rhodian coins.

While scholars do not know what the statue looked like, they do have a good idea of what the head and face looked like, as it was of a standard rendering at the time. The head would have had curly hair with evenly spaced spikes of bronze or silver flame radiating, similar to the images found on contemporary Rhodian coins.

Possible locations

While scholars generally agree that anecdotal depictions of the Colossus straddling the harbour's entry point have no historic or scientific basis, the monument's actual location remains a matter of debate. As mentioned above the statue is thought locally to have stood where two pillars now stand at the Mandraki port entrance.

The floor of the Fortress of St Nicholas, near the harbour entrance, contains a circle of sandstone blocks of unknown origin or purpose. Curved blocks of marble that were incorporated into the Fortress structure, but are considered too intricately cut to have been quarried for that purpose, have been posited as the remnants of a marble base for the Colossus, which would have stood on the sandstone block foundation.

While scholars generally agree that anecdotal depictions of the Colossus straddling the harbour's entry point have no historic or scientific basis, the monument's actual location remains a matter of debate. As mentioned above the statue is thought locally to have stood where two pillars now stand at the Mandraki port entrance.

The floor of the Fortress of St Nicholas, near the harbour entrance, contains a circle of sandstone blocks of unknown origin or purpose. Curved blocks of marble that were incorporated into the Fortress structure, but are considered too intricately cut to have been quarried for that purpose, have been posited as the remnants of a marble base for the Colossus, which would have stood on the sandstone block foundation.

Archaeologist Ursula Vedder postulates that the Colossus was not located in the harbour area at all, but rather was part of the Acropolis of Rhodes, which stood on a hill that overlooks the port area. The ruins of a large temple, traditionally thought to have been dedicated to Apollo, are situated at the highest point of the hill. Vedder believes that the structure would actually have been a Helios sanctuary, and a portion of its enormous stone foundation could have served as the supporting platform for the Colossus.

Archaeologist Ursula Vedder postulates that the Colossus was not located in the harbour area at all, but rather was part of the Acropolis of Rhodes, which stood on a hill that overlooks the port area. The ruins of a large temple, traditionally thought to have been dedicated to Apollo, are situated at the highest point of the hill. Vedder believes that the structure would actually have been a Helios sanctuary, and a portion of its enormous stone foundation could have served as the supporting platform for the Colossus.

Modern Colossus projects

In 2008, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

'' reported that a modern Colossus was to be built at the harbour entrance by the German artist Gert Hof leading a Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

-based team. It was to be a giant light sculpture made partially out of melted-down weapons from around the world. It would cost up to €200 million.

In December 2015, a group of European architects announced plans to build a modern Colossus bestriding two piers at the harbour entrance, despite a preponderance of evidence and scholarly opinion that the original monument could not have stood there. The new statue, tall (five times the height of the original), would cost an estimated US$283 million, funded by private donations and crowdsourcing. The statue would include a cultural centre, a library, an exhibition hall, and a lighthouse, all powered by solar panels. , no such plans have been carried out and the website for the project is offline.

See also

* Twelve Metal Colossi * ''The Colossus of Rhodes'' (Dalí) *'' The New Colossus'' *''The Rhodes Colossus

''The Rhodes Colossus'' is an editorial cartoon illustrated by English cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne and published by ''Punch'' magazine in 1892. It alludes to the Scramble for Africa during the New Imperialism period, in which the Euro ...

''

* List of tallest statues

References

Notes

References

Sources

* * Gabriel, Albert. ''Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique'' 56 (1932), pp. 331–59. * Haynes, D.E.L. "Philo of Byzantium and the Colossus of Rhodes" ''The Journal of Hellenic Studies'' 77.2 (1957), pp. 311–312. A response to Maryon. * Maryon, Herbert, "The Colossus of Rhodes" in ''The Journal of Hellenic Studies'' 76 (1956), pp. 68–86. A sculptor's speculations on the Colossus of Rhodes.Further reading

*Jones, Kenneth R. 2014. "Alcaeus of Messene, Philip V and the Colossus of Rhodes: A Re-Examination of Anth. Pal. 6.171." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 64, no. 1: 136–51. doi:10.1017/S0009838813000591. *Romer, John., and Elizabeth Romer. 1995. ''The Seven Wonders of the World: A History of the Modern Imagination.'' 1st American ed. New York: Henry Holt. *Woods, David. 2016. "On the Alleged Arab Destruction of the Colossus of Rhodes c. 653." ''Byzantion: Revue Internationale Des Etudes Byzantines'' 86: 441–51. {{DEFAULTSORT:Colossus Of Rhodes Ancient Rhodes Demolished buildings and structures in Greece Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Ancient Greece in art and culture Hellenistic architecture Hellenistic and Roman bronzes Lost sculptures Culture of Rhodes Helios Ancient Greek metalwork Buildings and structures in Rhodes (city) 3rd-century BC religious buildings and structures Buildings and structures completed in the 3rd century BC Buildings and structures demolished in the 3rd century BC 3rd-century BC establishments 3rd-century BC disestablishments Ancient Greek and Roman colossal statues