Colonization Attempts By Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

:''This article discusses Poland's involvement in the acquisition of colonial territories outside Europe. You may also be looking for:

CZY RZECZPOSPOLITA MIAŁA KOLONIE W AFRYCE I AMERYCE?

, Mówią wieki Some colonial territories for the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia were acquired by its third Duke and Gotthard's grandson

The first colony founded by Jacob was the New Courland (''Neu-Kurland'') on the

The first colony founded by Jacob was the New Courland (''Neu-Kurland'') on the

In 1651

In 1651

JSTOR

/ref> The League supported purchases of lands by Polish emigrants in places like

Kolonie Rzeczypospolitej

Opcja na Prawo, Nr. 7 {{DEFAULTSORT:Colonies of Poland Political history of Poland History of European colonialism

territorial changes of Poland

Poland is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north. The total ...

or polonization

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

.''

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

has never had any formal colonial territories, but over its history the acquisition of such territories has at times been contemplated, though never attempted. The closest Poland came to acquiring such territories was indirectly through the actions of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia ( la, Ducatus Curlandiæ et Semigalliæ; german: Herzogtum Kurland und Semgallen; lv, Kurzemes un Zemgales hercogiste; lt, Kuršo ir Žiemgalos kunigaikštystė; pl, Księstwo Kurlandii i Semigalii) was ...

, a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

ThePolish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in the ...

was interested in colonies as early as the mid-16th century. In a contractual agreement, signed with king Henri de Valois (see also Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles (Polish: ''Artykuły henrykowskie'', Latin: ''Articuli Henriciani'') were a permanent contract between the "Polish nation" (the szlachta, or nobility, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a n ...

), the nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

secured permission to settle in some oversea territories of the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, (''Please specify where these territories are,)'' but after de Valois's decision to opt for the crown of France and return to his homeland, the idea was abandoned.

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

On the basis of theUnion of Vilnius

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

(28 November 1561), Gotthard Kettler

Gotthard Kettler, Duke of Courland (also ''Godert'', ''Ketteler'', german: Gotthard Kettler, Herzog von Kurland; 2 February 1517 – 17 May 1587) was the last Master of the Livonian Order and the first Duke of Courland and Semigallia.

Biography

...

, the last Master of the Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after the ...

, created the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia ( la, Ducatus Curlandiæ et Semigalliæ; german: Herzogtum Kurland und Semgallen; lv, Kurzemes un Zemgales hercogiste; lt, Kuršo ir Žiemgalos kunigaikštystė; pl, Księstwo Kurlandii i Semigalii) was ...

in the Baltics and became its first Duke. It was a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. W ...

state of the Polish Kingdom. Soon afterward, by the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the pe ...

(1 July 1569), the Grand Duchy became the part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

. Dariusz KołodziejczykCZY RZECZPOSPOLITA MIAŁA KOLONIE W AFRYCE I AMERYCE?

, Mówią wieki Some colonial territories for the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia were acquired by its third Duke and Gotthard's grandson

Jacob Kettler

Jacob Kettler (german: link=no, Jakob von Kettler) (Latvian: Hercogs Jēkabs Ketlers) (28 October 1610 – 1 January 1682) was one of the greatest Baltic German Dukes of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1642–1682). He was intelligent, sp ...

. In his youth and during his studies abroad he was inspired by the wealth being brought back to various western European countries from their colonies. As a result, Kettler established one of the largest merchant fleets in Europe, with its main harbours in Windau (today Ventspils), and Libau (today Liepāja). The Commonwealth never concerned itself with the Duchy of Courland's colonial aspirations, even though in 1647 Kettler met with king Władysław IV Waza Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* W ...

, and suggested creation of a joint trade company, which would be active in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. However, the ailing king was not interested, and Kettler decided to act on his own.

New Courland

The first colony founded by Jacob was the New Courland (''Neu-Kurland'') on the

The first colony founded by Jacob was the New Courland (''Neu-Kurland'') on the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

island of Tobago

Tobago () is an List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, island and Regions and municipalities of Trinidad and Tobago, ward within the Trinidad and Tobago, Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trini ...

. However, three initial attempts to establish a settlement (in 1637, 1639 and 1642) failed. The fourth was founded in 1654, but eventually in 1659 was taken over by a competing Dutch colony, also founded on the island in 1654. Courland regained the island after the Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660Evans (2008), p.55 ( pl, Pokój Oliwski, sv, Freden i Oliva, german: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).Frost (2000), p.183 ...

in 1660 but abandoned it in 1666. It briefly attempted to reestablish colonies there again in 1668 and in 1680 (that lasted to 1683). The final attempt in 1686 lasted until 1690.

Gambia

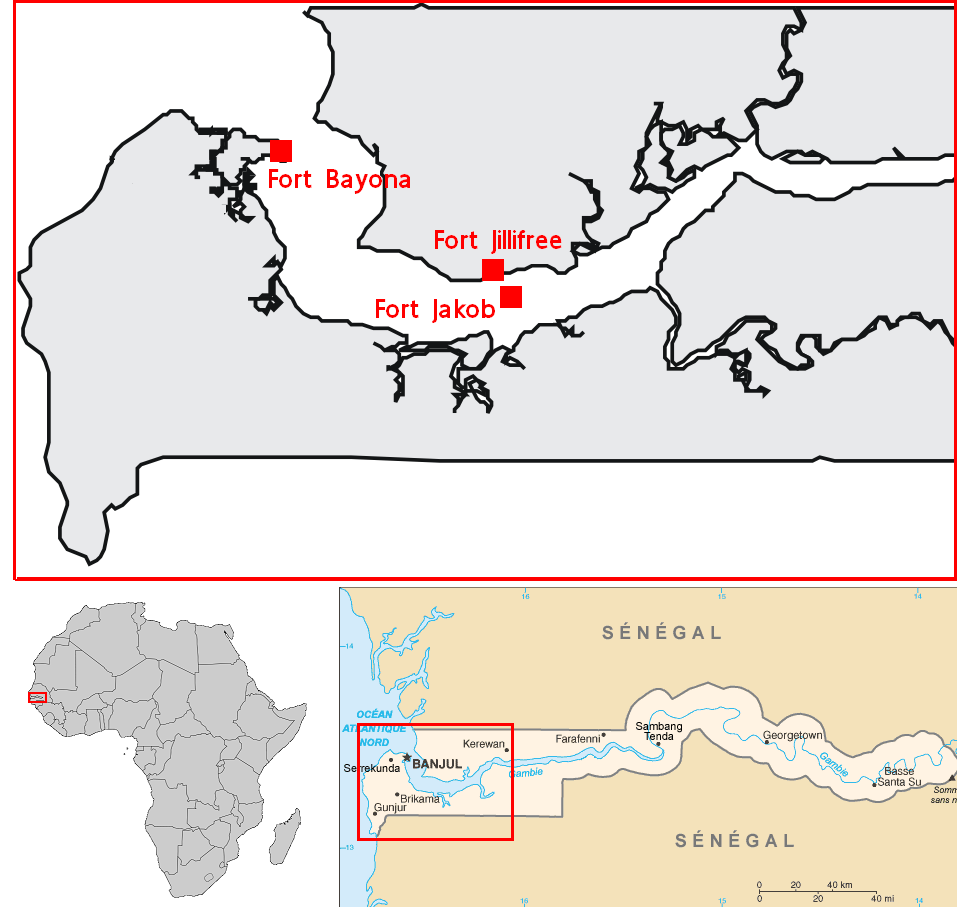

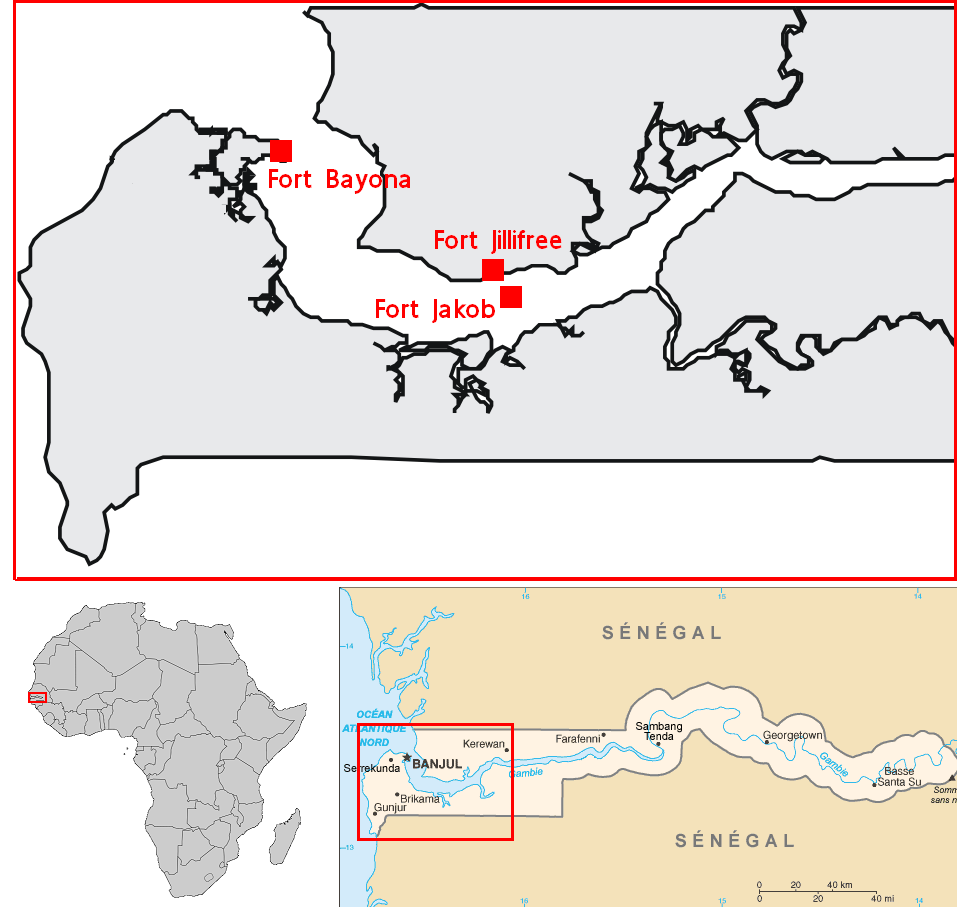

In 1651

In 1651 Courland

Courland (; lv, Kurzeme; liv, Kurāmō; German and Scandinavian languages: ''Kurland''; la, Curonia/; russian: Курляндия; Estonian: ''Kuramaa''; lt, Kuršas; pl, Kurlandia) is one of the Historical Latvian Lands in western Latvia. ...

bought James Island (then called St. Andrews Island by the Europeans) from a local tribe, establishing Fort James there and renaming the island. Courland also took other local land including St. Mary Island (modern day ) and Fort Jillifree. The colony exported sugar, tobacco, coffee, cotton, ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices ...

, indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

, rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Ph ...

, cocoa

Cocoa may refer to:

Chocolate

* Chocolate

* ''Theobroma cacao'', the cocoa tree

* Cocoa bean, seed of ''Theobroma cacao''

* Chocolate liquor, or cocoa liquor, pure, liquid chocolate extracted from the cocoa bean, including both cocoa butter and ...

, tortoise shells, tropical birds and their feathers. The governors maintained good relations with the locals, but came into conflict with other European powers, primarily Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, and the United Provinces. The Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

annexed the Courland territories in Africa, bringing an end to their presence on the continent.

Toco

The final Courish attempt to establish a colony involved the settlement near modernToco

Toco is the most northeasterly village on the island of Trinidad in Trinidad and Tobago. The island of Tobago is to the northeast, making Toco the closest point in Trinidad to the sister island. The name Toco was ascribed to the area by its early ...

on Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

.

Partitioned Poland

Cameroon expedition

In 1882, almost a century after Poland was partitioned and lost its independence, Polish nobleman and officer of Russian Imperial Fleet, Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński organized an expedition toCameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

. Officially that was an exploration expedition, but unofficially the expedition was looking for a place a Polish community could be founded abroad. He had no official support from the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, nor from its puppet Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

, but was backed by a number of influential Poles, including Boleslaw Prus, and Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish writer, novelist, journalist and Nobel Prize laureate. He is best remembered for his historical novels, especi ...

. On 13 December 1882, accompanied by Leopold Janikowski

Leopold Janikowski (14 November 1855 - 8 December 1942) was a Polish people, Polish explorer and ethnographer.

Biography

Leopold Ludwik Janikowski was born on 14 November 1855 in Dąbrówka, now part of Warsaw (Białołęka) in Poland, son of Ja ...

and Klemens Tomczek, Rogoziński left French port of Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

, aboard a ship ''Lucja Malgorzata'', with French and Polish flags. The expedition was a failure, and he returned to Europe, trying to collect more money for his project. Finally, after second expedition, Rogoziński found himself in Paris, where he died 1 December 1896.

Meanwhile, Cameroon was being slowly annexed by the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

. In 1884 Rogoziński signed an agreement with a British representative, who was to provide support for treaties he signed with Cameroonian chieftains, but next year, at the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

, the British government decided against pursuing any claims in the region and acceded to German claims (see Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern p ...

).

Second Polish Republic

Poland regained independence in theaftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

. While colonization was never a major focus of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

, certain organizations like the Maritime and Colonial League

The Maritime and Colonial League (Polish: ''Liga Morska i Kolonialna'') was a mass Polish social organization, created in 1930 out of the Maritime and River League (Liga Morska i Rzeczna). In the late 1930s it was directed by general Mariusz Zarus ...

supported the idea of creating Polish colonies. The Maritime and Colonial League

The Maritime and Colonial League (Polish: ''Liga Morska i Kolonialna'') was a mass Polish social organization, created in 1930 out of the Maritime and River League (Liga Morska i Rzeczna). In the late 1930s it was directed by general Mariusz Zarus ...

traces its origins to the ''Polska Bandera'' (Polish Banner) organization founded on 1 October 1918. Taras Hunczak, ''Polish Colonial Ambitions in the Inter-War Period'', Slavic Review, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Dec., 1967), pp. 648-656JSTOR

/ref> The League supported purchases of lands by Polish emigrants in places like

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

. The League became highly influential in shaping the government's policies with regards to Polish Merchant Marine, despite its long and ongoing campaign (publications, exhibitions, speeches, lobbying, etc.) and public support, it has however never succeeded in following up with its plans to obtain a colonial territory for Poland. Furthermore, in 1926, ''Colonial Society'' (''Towarzystwo Kolonizacyjne'') was founded in Warsaw. Its task was to direct Polish emigrants to South America, and the Society soon became active there, mostly in Brazilian state of Espirito Santo

''Espirito'' (Brazilian for "Spirit") is the second album by Lawson Rollins. Rollins composed all of the music and co-produced the album with Persian-American musician and producer Shahin Shahida (of Shahin & Sepehr) and multi-platinum producer Do ...

.

Some historians, such as Tadeusz Piotrowski, have characterized government policies supporting interwar Polish settlement in modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

as colonization (see Osadnik

Osadniks ( pl, osadnik/osadnicy, "settler/settlers, colonist/colonists") were veterans of the Polish Army and civilians who were given or sold state land in the ''Kresy'' (current Western Belarus and Western Ukraine) territory ceded to Poland by P ...

). Using a highly theoretical framework, one scholar argues that Poland's settlement projects, in particular the Liberian affair, should be seen as a rework of the New South ideology that considered Africans as people who could only implement hard labour such as land cultivation and assume inferior economic and political positions, as attributed to African-Americans in the New South. Such projects, the argument goes, would lead to the prioritization of European lives over Africans' with economic and racial implications. In contrast, several Polish and Polish-American historians attribute fewer racist motivations to Poland's attempts in Africa and Latin America. They point out that Poland's largely economic attempts to acquire tropical materials unavailable in continental Europe became infused with counterproductive colonial discourse still popular across Europe at the time. The Polish projects, less politically expansionist than they might seem, fulfilled specific functions in Polish foreign policy not only in relation to the question of Jewish emigration but also in Polish-German relations.

The following regions were considered for Polish colonization during the interwar period:

* Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

( Paraná region): Polish emigration to that region began even before World War I, in the 1930s approximately 150,000 Poles lived there (18.3% of local inhabitants). Government-sponsored settlement action began there in 1933, after the Maritime and Colonial League, together with other organizations, had bought a total of 250,000 hectares of land. Brazilian government, fearing that the Poles might plan to annex part of Brazil, reacted very quickly, limiting activities of Polish organizations. Since the government in Warsaw did not want to intervene, the project ended by late 1930s See also: Polish minority in Brazil

* Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

(near Ucayali River

The Ucayali River ( es, Río Ucayali, ) is the main headstream of the Amazon River. It rises about north of Lake Titicaca, in the Arequipa region of Peru and becomes the Amazon at the confluence of the Marañón close to Nauta city. The city of ...

): positively assessed in 1927. In January 1928, Polish expedition headed for the area of the Ucayali, to check possibilities of creation of settlements for farmers on several thousand hectares of rainforest. Soon afterward, first settlers arrived in Peru, but because of the Great Crisis, the government in Warsaw ceased to fund the action. Private donations were insufficient, furthermore, the first settlers discovered the local condition to be much worse than advertised. In 1933, the contract with the Peruvians was terminated, and to avoid international scandal, all settlers returned to Poland.

* Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

: On 14 December 1928, the Maritime and Colonial League sent an expedition to Angola, which was then a Portuguese colony. The plan was to try to bring as many Polish immigrants as possible, and then try to purchase some land from the Portuguese. However, after five years, one of the first pioneers in Angola, Michal Zamoyski, wrote: "Personally, I would not persuade anybody to live in Angola". Living conditions were difficult, profits were marginal, and the idea was abandoned.

* Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

: Liberian and Polish governments had good relations because of Polish support for Liberia in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. In the fall of 1932, the League of Nations drafted a plan which projected turning Liberia into a protectorate, governed by one of members of the League. The plan was the result of internal policies of Liberia, where slavery was widespread. Since Poland was not regarded by the Liberians as a country which had colonial aspirations, in late 1932 unofficial envoy of Liberian government, dr Leo Sajous, came to Warsaw to ask for help. In April 1933, an agreement was signed between Liberia and the Maritime and Colonial League. The Africans agreed to lease minimum of 60 hectares of land to Polish farmers, for a period of 50 years. Polish businesses were awarded the status of the most favoured nation, and Warsaw was permitted to found a society to exploit natural resources of Liberia. Liberian government invited settlers from Poland in 1934. Altogether, the Liberians granted to Polish settlers 50 plantations, with total area of . In the second half of 1934, six Polish farmers left for Liberia: Gizycki, Szablowski, Brudzinski, Chmielewski, Januszewicz and Armin. The project was not fully supported by the Polish government but rather by the Maritime League; only few dozens of Poles took on that offer (because of Liberian requests that the settlers should bring significant capital) and their ventures proved to be, on the most part, unprofitable. The original of the agreement has been lost, but, according to some sources, there was a secret protocol that allowed Poland to draft 100,000 African soldiers. The Polish involvement in Liberia was harshly opposed by the United States of America, creator of the nation of Liberia. As a result of American pressure, in 1938 the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs closed the office of the Maritime and Colonial League in Monrovia

Monrovia () is the capital city of the West African country of Liberia. Founded in 1822, it is located on Cape Mesurado on the Atlantic coast and as of the 2008 census had 1,010,970 residents, home to 29% of Liberia’s total population. As the ...

.

* Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

: plans for colonization of Mozambique were tied to business investments by some Polish enterprise near the late 1930s and never progressed beyond normal foreign investment (acquisition of agricultural lands and mines).

* Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

: another plan for acquiring the French colony of Madagascar by the Polish government was discussed in 1926, but the idea was deemed to be unfeasible. The idea was revisited in the 1930s, when it was proposed that Polish Jews, who were perceived to dominate the Polish professions, be encouraged to emigrate. At one point, Polish foreign minister Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Poles, Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minist ...

bluntly proposed that Madagascar be used as a "dumping ground" for Poland's "surplus" Jewish population. The Polish government proposed the concept of Jewish emigration to Madagascar to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in 1936 and sent a delegation to evaluate the island in 1937. France, seeking to strengthen its ties with Poland and discourage Polish-German cooperation, participated in the venture, which included the French official Marcel Moutet. Warsaw sent a special delegation to Madagascar, under major of the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stret ...

Mieczyslaw Lepecki. The plan is variously described as having come to nought shortly after the 1937 expedition or as being terminated by the German Invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

in September 1939.

* Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

and Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

: Various Polish authors, unsupported by the government, expressed interests in this region on the grounds that they were in part discovered by Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński and that Europe owed a general debt to Poland for the Polish-Soviet War.

* Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

was also considered as a destination for Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lo ...

. Colonel Josef Beck, then Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

, supported the concept.

See also

*Morska Wola

Morska Wola was a Polish settlement, located in Brazil, in the state of Paraná. It was founded by the Maritime and Colonial League around 1934. The League purchased land from local Indigenous Brazilian tribes and carried out an extensive promot ...

* Haren, Germany

*Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation

European colonialism and colonization was the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over other societies and territories, founding a colony, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically. For example, colo ...

Notes

External links

* Marek Arpad KowalskiKolonie Rzeczypospolitej

Opcja na Prawo, Nr. 7 {{DEFAULTSORT:Colonies of Poland Political history of Poland History of European colonialism