Collapse of the Ottoman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) began with the

The Capitulations were the main discussion of economic policy during the period. It used to be believed incoming foreign assistance with capitulation could benefit the Empire. Ottoman officials, representing different jurisdictions, sought bribes at every opportunity and withheld the proceeds of a vicious and discriminatory tax system. This ruined every struggling industry by the graft, and fought against every show of independence on the part of Empire's many subject peoples.

The

The Capitulations were the main discussion of economic policy during the period. It used to be believed incoming foreign assistance with capitulation could benefit the Empire. Ottoman officials, representing different jurisdictions, sought bribes at every opportunity and withheld the proceeds of a vicious and discriminatory tax system. This ruined every struggling industry by the graft, and fought against every show of independence on the part of Empire's many subject peoples.

The

After nine months into the new government, discontent found expression in a fundamentalist movement which attempted to dismantle Constitution and revert it with a monarchy. The

After nine months into the new government, discontent found expression in a fundamentalist movement which attempted to dismantle Constitution and revert it with a monarchy. The

Italy declared war, the

Italy declared war, the

When the Italian War and the counterinsurgency operations in Albania and

When the Italian War and the counterinsurgency operations in Albania and

The empire agreed to a ceasefire on 2 December, and its territory losses were finalized in 1913 in the treaties of

The empire agreed to a ceasefire on 2 December, and its territory losses were finalized in 1913 in the treaties of

In May 1913 a German military mission assigned

In May 1913 a German military mission assigned

The Albanians of

The Albanians of

In 1908, the

In 1908, the  On 15 January 1912, the Ottoman parliament dissolved and political campaigns began almost immediately. After the election, on 5 May 1912, Dashnak officially severed the relations with the Ottoman government; a public declaration of the Western Bureau printed in the official announcement was directed to "Ottoman Citizens." The June issue of

On 15 January 1912, the Ottoman parliament dissolved and political campaigns began almost immediately. After the election, on 5 May 1912, Dashnak officially severed the relations with the Ottoman government; a public declaration of the Western Bureau printed in the official announcement was directed to "Ottoman Citizens." The June issue of  During the Spring of 1913, the provinces faced increasingly worse relations between Kurds and Armenians that created an urgent need for the ARF to revive its self-defence capability. In 1913, the

During the Spring of 1913, the provinces faced increasingly worse relations between Kurds and Armenians that created an urgent need for the ARF to revive its self-defence capability. In 1913, the

In 1908, after the overthrow of Sultan, the Hamidiye was disbanded as an organized force, but as they were "tribal forces" before official recognition by the Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1892, they stayed as "tribal forces" after dismemberment. The Hamidiye Cavalry is often described as a failure because of its contribution to tribal feuds.

Shaykh Abd al Qadir in 1910 appealed to the CUP for an autonomous Kurdish state in the east. That same year, Said Nursi travelled through the Diyarbakir region and urged Kurds to unite and forget their differences, while still carefully claiming loyalty to the CUP. Other Kurdish

In 1908, after the overthrow of Sultan, the Hamidiye was disbanded as an organized force, but as they were "tribal forces" before official recognition by the Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1892, they stayed as "tribal forces" after dismemberment. The Hamidiye Cavalry is often described as a failure because of its contribution to tribal feuds.

Shaykh Abd al Qadir in 1910 appealed to the CUP for an autonomous Kurdish state in the east. That same year, Said Nursi travelled through the Diyarbakir region and urged Kurds to unite and forget their differences, while still carefully claiming loyalty to the CUP. Other Kurdish

The text of the Treaty of Sèvres was not made public to the Ottoman public until May 1920. The Allies decided that the Empire would be left only a small area in Northern and Central Anatolia to rule. Contrary to general expectations, the Sultanate along with the Caliphate was not terminated, and it was allowed to retain capitol and a small strip of territory around the city, but not the straits. The shores of the

The text of the Treaty of Sèvres was not made public to the Ottoman public until May 1920. The Allies decided that the Empire would be left only a small area in Northern and Central Anatolia to rule. Contrary to general expectations, the Sultanate along with the Caliphate was not terminated, and it was allowed to retain capitol and a small strip of territory around the city, but not the straits. The shores of the

File:Portrait of Abdul Hamid II of the Ottoman Empire.jpg, Abdülhamid II

File:Kopyası 35-SULTAN REŞAT.jpg, Mehmed V

File:VI Mehmet Vahidettin.jpg, Mehmed VI

Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Constit ...

which restored the constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in c ...

with a two-stage electoral system for the Ottoman parliament

The General Assembly ( tr, Meclis-i Umumî (French romanization: "Medjliss Oumoumi" ) or ''Genel Parlamento''; french: Assemblée Générale) was the first attempt at representative democracy by the imperial government of the Ottoman Empire. Als ...

. At the same time, a nascent movement called Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep millets ...

was promoted in an attempt to maintain the unity of the Empire, emphasising a collective Ottoman nationalism regardless of religion or ethnicity. Within the empire, the new constitution was initially seen positively, as an opportunity to modernize state institutions and resolve inter-communal tensions between different ethnic groups.

Instead, this period became the story of the twilight struggle of the Empire. Despite military reforms

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, the Ottoman Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

met with disastrous defeat in the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

(1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

(1912–1913), resulting in the Ottomans being driven out of North Africa and nearly out of Europe. Continuous unrest leading up to World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

resulted in the 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

, the 1912 Ottoman coup d'état

The 1912 Ottoman coup d'état (17 July 1912) was a military coup in the Ottoman Empire against the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government (elected during the 1912 general elections) by a group of military officers calling themselves the ...

and the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état

The 1913 Ottoman coup d'état (January 23, 1913), also known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte ( tr, Bâb-ı Âlî Baskını), was a coup d'état carried out in the Ottoman Empire by a number of Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) members led by ...

. The Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) government became increasingly radicalised during this period, and conducted ethnic cleansing and genocide against the empire's Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

, Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

citizens, events collectively referred to as the Late Ottoman genocides

The late Ottoman genocides is a historiographical theory which sees the concurrent Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides that occurred during the 1910s–1920s as parts of a single event rather than separate events which were initiated by the Y ...

. Ottoman participation in World War I ended with defeat and the partition of the empire's remaining territories under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

. The treaty, formulated at the conference of London

List of conferences in London (chronological):

* London Conference of 1830 guaranteed the independence of Belgium

* London Conference of 1832 convened to establish a stable government in Greece

* London Conference of 1838–1839 preceded the Tr ...

, allocated nominal land to the Ottoman state and allowed it to retain the designation of "Ottoman Caliphate" (similar to the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

, a sacerdotal Sacerdotalism (from Latin ''sacerdos'', priest, literally one who presents sacred offerings, ''sacer'', sacred, and ''dare'', to give) is the belief in some Christian churches that priests are meant to be mediators between God and humankind. The und ...

-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy), ...

state ruled by the Catholic Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

), leaving it severely weakened. One factor behind this arrangement was Britain's desire to thwart the Khilafat Movement

The Khilafat Movement (1919–24), also known as the Caliphate movement or the Indian Muslim movement, was a pan-Islamist political protest campaign launched by Muslims of British India led by Shaukat Ali, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Hakim Ajma ...

.

The occupation of Constantinople

The occupation of Istanbul ( tr, İstanbul'un İşgali; 12 November 1918 – 4 October 1923), the capital of the Ottoman Empire, by United Kingdom, British, France, French, Italy, Italian, and Greece, Greek forces, took place in accordance with ...

(Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

), along with the occupation of Smyrna

The city of Smyrna (modern-day İzmir) and surrounding areas were under Greek military occupation from 15 May 1919 until 9 September 1922. The Allied Powers authorized the occupation and creation of the Zone of Smyrna ( el, Ζώνη Σμύρν� ...

( Izmir), mobilized the Turkish national movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

, which ultimately won the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

. The formal abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate was performed by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey ( tr, ), usually referred to simply as the TBMM or Parliament ( tr, or ''Parlamento''), is the unicameral Turkish legislature. It is the sole body given the legislative prerogatives by the Turkish Consti ...

on 1 November 1922. The Sultan was declared ''persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (Latin: "person not welcome", plural: ') is a status applied by a host country to foreign diplomats to remove their protection of diplomatic immunity from arrest and other types of prosecution.

Diplomacy

Under Article 9 of the ...

'' from the lands the Ottoman Dynasty had ruled since 1299.

Background

Social conflicts

Europe became dominated by nation states with therise of nationalism in Europe

The rise of nationalism in Europe was spurred by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. American political science professor Leon Baradat has argued that “nationalism calls on people to identify with the interests of their national group ...

. The 19th century saw the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire

The rise of the Western notion of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman ''millet'' concept. An understanding of the concept of nationhood prevalent in the Ottoman Empire, which was different from the cu ...

which resulted in the establishment of an independent Greece in 1821, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

in 1835, and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

in 1877-1878. Unlike the European nations, the Ottoman Empire made little attempt to integrate conquered peoples through cultural assimilation. Instead, Ottoman policy was to rule through the millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

system, consisting of confessional communities for each religion.

The Empire never fully integrated its conquests economically and therefore never established a binding link with its subjects. Between 1828 and 1908, the Empire tried to catch up with industrialization and a rapidly emerging world market by reforming state and society. By virtue of the Treaty of Balta Liman (1838) between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire, the latter “will abolish all monopolies, allow British merchants and their collaborators to have full access to all Ottoman markets and will be taxed equally to local merchants”. As a result of this treaty, “the Ottomans were unable to protect their manufactures or raise revenues for investments in development projects”. This treaty enabled English manufacturers to sell their wares cheaply in the Ottoman Empire, and consequently undermined Ottoman efforts to industrialize. Despite these hurdles, “It speaks to the determination of the Ottomans that they sought to launch an industrial revolution despite their adverse fiscal circumstances. In the decade starting in 1841, the Ottomans had set up to the west of Istanbul a complex of state-owned industries that included spinning and weaving mills, a foundry, steam-operated machine works, and a boatyard for the construction of small steamships. In the words of Edward Clark: “In variety as well as in number, in planning, in investment, and in attention given to internal sources of raw materials these manufacturing enterprises far surpassed the scope of all previous efforts and mark this period as unique in Ottoman history.”

Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep millets ...

, originating from Young Ottomans

The Young Ottomans () were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman Turkish intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the Tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans so ...

who were inspired by the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

social contract theorists Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principa ...

and Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, promoted equality among the millets and stated that every subject was equal before the law. Proponents of Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep millets ...

believed accepting all separate ethnicities and religions as ''Ottomans'' could solve social issues. Following the Tanzimat reforms

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. ...

, major reforms were introduced into the structure of the Empire. The essence of the millet system was not dismantled, but secular organizations and policies were established. Primary education and conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

were to be applied to non-Muslims and Muslims alike. Michael Hechter

Michael Hechter is an American sociologist and Foundation Professor of Political Science at Arizona State University. He is also Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Washington.

Hechter first became known for his research in compa ...

argues that the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire was the result of a backlash against Ottoman attempts to institute more direct and central forms of rule over populations which had previously had greater autonomy.

Economic issues

The Capitulations were the main discussion of economic policy during the period. It used to be believed incoming foreign assistance with capitulation could benefit the Empire. Ottoman officials, representing different jurisdictions, sought bribes at every opportunity and withheld the proceeds of a vicious and discriminatory tax system. This ruined every struggling industry by the graft, and fought against every show of independence on the part of Empire's many subject peoples.

The

The Capitulations were the main discussion of economic policy during the period. It used to be believed incoming foreign assistance with capitulation could benefit the Empire. Ottoman officials, representing different jurisdictions, sought bribes at every opportunity and withheld the proceeds of a vicious and discriminatory tax system. This ruined every struggling industry by the graft, and fought against every show of independence on the part of Empire's many subject peoples.

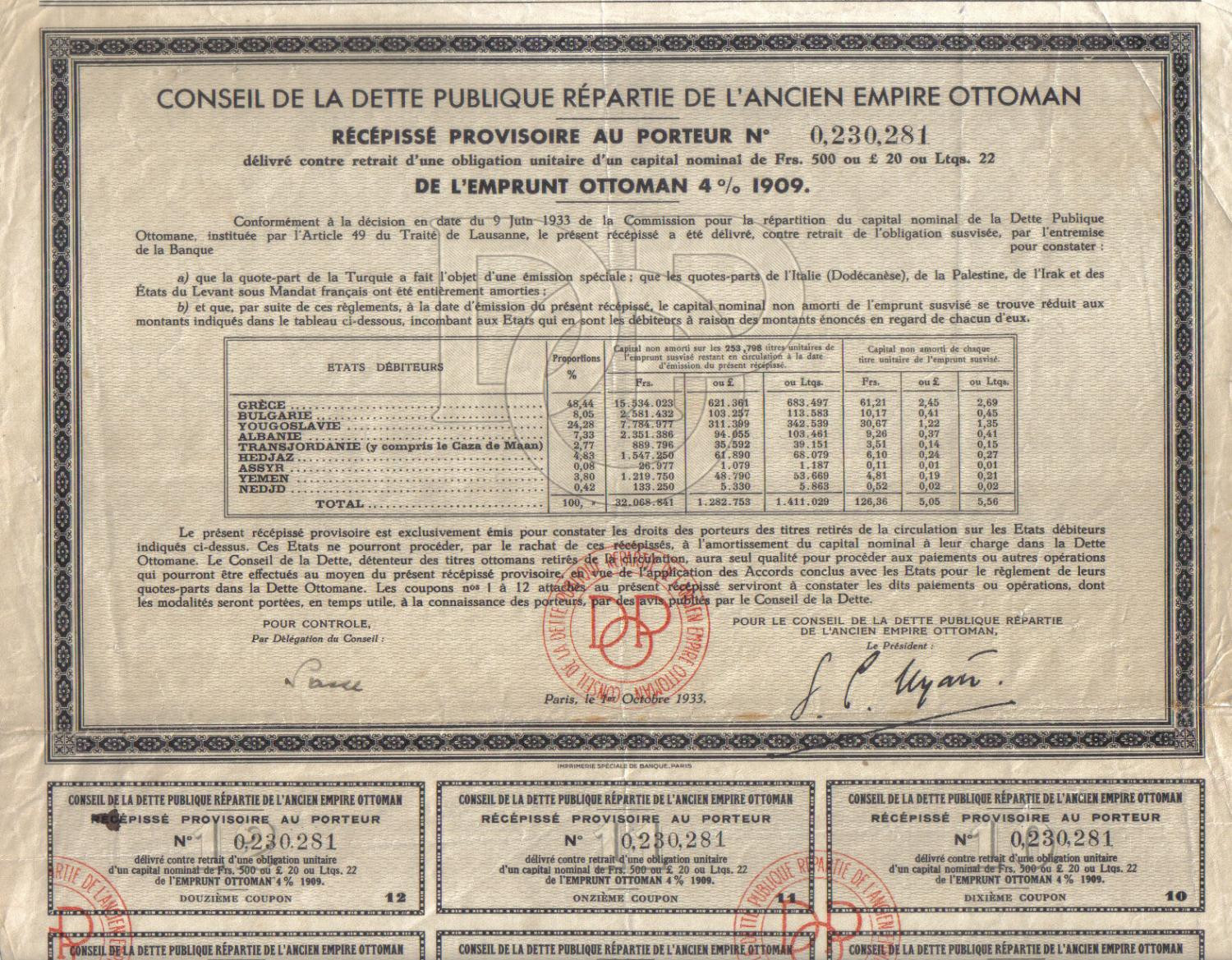

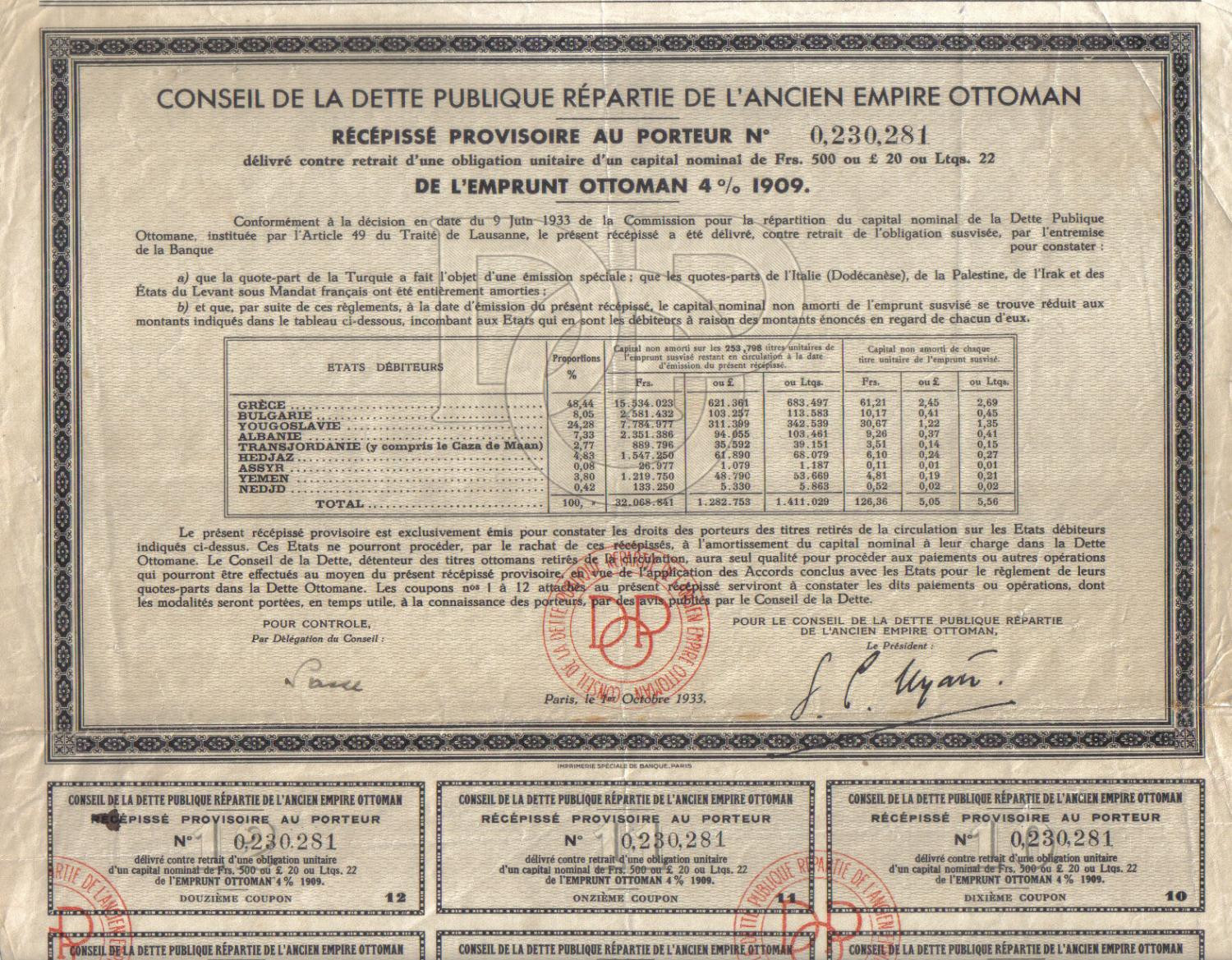

The Ottoman public debt

The Ottoman public debt was a term which dated back to 24 August 1855,< ...

was part of a larger scheme of control by the European powers, through which the commercial interests of the world had sought to gain advantages that may not have been of the Empire's interest. The debt was administered by the Ottoman Public Debt Administration

The Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA) ( ota, دیون عمومیهٔ عثمانیه واردات مخصصه ادارهسی, script=Arab, Düyun-u Umumiye-i Osmaniye Varidat-ı Muhassasa İdaresi, or simply as it was popularly known), ...

and its power was extended to the Imperial Ottoman Bank

The Ottoman Bank ( tr, Osmanlı Bankası), known from 1863 to 1925 as the Imperial Ottoman Bank (french: Banque Impériale Ottomane, ota, بانق عثمانی شاهانه) and correspondingly referred to by its French acronym BIO, was a bank ...

(or Central bank). The total pre-World War debt of Empire was $716,000,000. France had 60 percent of the total. Germany had 20 percent. The United Kingdom owned 15 percent. The Ottoman Debt Administration controlled many of the important revenues of the Empire. The Council had power over financial affairs; its control even extended to determine the tax on livestock in the districts.

Young Turk Revolution

In July 1908, theYoung Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Constit ...

changed the political structure of the Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) rebelled against the absolute rule of Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

to establish the Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era ( ota, ایكنجی مشروطیت دورى; tr, İkinci Meşrutiyet Devri) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the G ...

. On 24 July 1908, Abdul Hamid II capitulated and restored the Ottoman constitution of 1876

The Constitution of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, قانون أساسي, Kānûn-ı Esâsî, lit= Basic law; french: Constitution ottomane), also known as the Constitution of 1876, was the first constitution of the Ottoman Empire. Written by members ...

.

The revolution created multi-party

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in c ...

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

. Once underground, the Young Turk movement declared its parties. Among them was " Union and Progress" (CUP), and the "Ottoman Liberty Party

The Ottoman Liberty Party ( ota, Osmanlı Ahrar Fırkası) was a short-lived liberal political party in the Ottoman Empire during the Second Constitutional Era. It was founded by Prince Sabahaddin, Ahmet Samim, Suat Soyer, Ahmet Reşit Rey, M ...

."

There were smaller parties such as Ottoman Socialist Party

The Ottoman Socialist Party ( tr, Osmanlı Sosyalist Fırkası, OSF) was the first Turkish socialist political party, founded in the Ottoman Empire in 1910.

Ottoman Socialist Party (1910–1913)

Before the formation of the party, socialist par ...

and ethnic parties which included People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section)

250px, Dimo Hadzhidimov, Todor Panitsa and Yane Sandanski">Todor_Panitsa.html" ;"title="Dimo Hadzhidimov, Todor Panitsa">Dimo Hadzhidimov, Todor Panitsa and Yane Sandanski with the Young Turks

The People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section) ...

, Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs

Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs (also known as ''Union of the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs'') ( bg, Съюз на българските конституционни клубове) was an ethnic Bulgarian political party in the Ottoman Empire, ...

, Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party in Palestine (Poale Zion) Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party in Palestine (Poale Zion) was a political party, founded in 1906 in Ottoman Palestine. Its founders belonged to a group of Jewish settlers, that had taken part in self-defense during the Homel pogrom. It was th ...

, Al-Fatat

Al-Fatat or the Young Arab Society ( ar, جمعية العربية الفتاة, Jam’iyat al-’Arabiya al-Fatat) was an underground Arab nationalist organization in the Ottoman Empire. Its aims were to gain independence and unify various Arab te ...

(also known as the Young Arab Society; ''Jam’iyat al-'Arabiya al-Fatat''), Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization

The Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization or (Hizb al-lamarkaziyya al-idariyya al'Uthmani) (OPAD) was a political party in the Ottoman Empire founded in January 1913. Based in Cairo, OPAD called for the reform of the Ottoman provincial ...

, and Armenians were organized under the Armenakan, Hunchakian and Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

(ARF/Dashnak).

At the onset, there was a desire to remain unified, and the competing groups wished to maintain a common country. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; bg, Вътрешна Македонска Революционна Организация (ВМРО), translit=Vatrešna Makedonska Revoljucionna Organizacija (VMRO); mk, Внатр� ...

(IMRO) collaborated with the members of the CUP, and Greeks and Bulgarians joined under the second biggest party, the Liberty Party. The Bulgarian federalist wing welcomed the revolution, and they later joined mainstream politics as the People's Federative Party. The former centralists of the IMRO formed the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs

Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs (also known as ''Union of the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs'') ( bg, Съюз на българските конституционни клубове) was an ethnic Bulgarian political party in the Ottoman Empire, ...

, and, like the PFP, they participated in 1908 Ottoman general election

General elections were held in November and December 1908 for all 288 seats of the Chamber of Deputies of the Ottoman Empire, following the Young Turk Revolution which established the Second Constitutional Era. They were the first elections conte ...

.

Further disintegration

Thede jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

Bulgarian Declaration of Independence

The ''de jure'' independence of Bulgaria ( bg, Независимост на България, ''Nezavisimost na Bǎlgariya'') from the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed on in the old capital of Tarnovo by Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria, who afte ...

on from the Empire was proclaimed in the old capital of Tarnovo

Veliko Tarnovo ( bg, Велико Търново, Veliko Tărnovo, ; "Great Tarnovo") is a town in north central Bulgaria and the administrative centre of Veliko Tarnovo Province.

Often referred as the "''City of the Tsars''", Veliko Tarnovo ...

by Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria

, image = Zar Ferdinand Bulgarien.jpg

, caption = Ferdinand in 1912

, reign = 5 October 1908 –

, coronation =

, succession = Tsar of Bulgaria

, predecessor = Himself as Prince

, successor = Boris III

, reig ...

, who afterwards took the title "Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

".

The Bosnian crisis on 6 October 1908 erupted when Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

announced the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

, territories formally within the sovereignty of the Empire. This unilateral action was timed to coincide with Bulgaria's declaration of independence (5 October) from the Empire. The Ottoman Empire protested Bulgaria's declaration with more vigour than the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it had no practical prospects of governing. A boycott of Austro-Hungarian goods and shops occurred, inflicting commercial losses of over 100,000,000 ''kronen

Kronen Brauerei, also known as Private Brewery Dortmund Kronen, was one of the oldest brewery, breweries in Westphalia and has its headquarters at the Old Market in Dortmund. The company was able to look back on more than 550 years of brewing ...

'' on Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary agreed to pay the Ottomans ₤2.2 million for the public land in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Bulgarian independence could not be reversed.

Just after the revolution in 1908, the Cretan deputies declared union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

with Greece, taking advantage of the revolution as well as the timing of Zaimis's vacation away from the island. 1908 ended with the issue still unresolved between the Empire and the Cretans. In 1909, after the parliament elected its governing structure (first cabinet), the CUP majority decided that if order was maintained and the rights of Muslims were respected, the issue would be solved with negotiations.

The Second Constitutional Era (1908–1920)

New Parliament

1908 Ottoman general election

General elections were held in November and December 1908 for all 288 seats of the Chamber of Deputies of the Ottoman Empire, following the Young Turk Revolution which established the Second Constitutional Era. They were the first elections conte ...

was preceded by political campaigns. In the summer of 1908, a variety of political proposals were put forward by the CUP. The CUP stated in its election manifesto that it sought to modernize the state by reforming finance and education, promoting public works and agriculture, and the principles of equality and justice. Regarding nationalism, (Armenian, Kurd, Turkic..) the CUP identified the Turks as the "dominant nation" around which the empire should be organized, not unlike the position of Germans in Austria-Hungary. According to Reynolds, only a small minority in the Empire occupied themselves with Pan-Turkism

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), with its aim bei ...

, at least in 1908.

The election was held in October and November 1908. CUP-sponsored candidates were opposed by the Liberals. The latter became a centre for those opposing the CUP. Sabaheddin Bey, who returned from his long exile, believed that in non-homogeneous provinces a decentralized government was best. The Liberals were poorly organized in the provinces, and failed to convince minority candidates to contest the election under the Liberty Party banner; it also failed to tap into the continuing support for the old regime in less developed areas.

During September 1908, the important Hejaz Railway opened, construction of which had started in 1900. Ottoman rule was firmly re-established in Hejaz and Yemen with the railroad from Damascus to Medina. Historically, Arabia's interior was mostly controlled by playing one tribal group off against another. As the railroad finished, opposing Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

Islamic fundamentalists reasserted themselves under the political leadership of Abdul al-Aziz Ibn Saud.

Christian communities of the Balkans felt that the CUP no longer represented their aspirations. They had heard the CUP's arguments before, under the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. ...

reforms:

The system became multi-headed, with old and new structures coexisting, until the CUP took full control of the government in 1913 and, under the chaos of change, power was exercised without accountability.

The Senate of the Ottoman Empire

The Senate of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, مجلس أعيان, or ; tr, Ayan Meclisi; lit. "Assembly of Notables"; french: Chambre des Seigneurs/Sénat (, with 'old')

* el, γερουσία (, from , 'old man')

, group=note) was the upper hous ...

was opened by the Sultan on 17 December 1908. The new year brought the results of 1908 elections. Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

gathered on 30 January 1909. The CUP needed a strategy to realize their Ottomanist ideals.

In 1909, public order laws and police were unable to maintain order; protesters were prepared to risk reprisals to express their grievances. In the three months following the inauguration of the new regime there were more than 100 strikes, constituting three-quarters of the labor force of the Empire, mainly in Constantinople and Salonika (Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

). During previous strikes (Anatolian tax revolts in 1905-1907

Anatolian or anatolica may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the region Anatolia

* Anatolians, ancient Indo-European peoples who spoke the Anatolian languages

* Anatolian High School, a type of Turkish educational institution

* Anato ...

) the Sultan remained above criticism and bureaucrats and administrators were deemed corrupt; this time CUP took the blame. In the parliament the Liberty Party accused the CUP of authoritarianism. Abdul Hamid's Grand Viziers Said and Kâmil Pasha

Mehmed Kâmil Pasha ( ota, محمد كامل پاشا مصري زاده; tr, Kıbrıslı Mehmet Kâmil Paşa, "Mehmed Kamil Pasha the Cypriot"), also spelled as Kiamil Pasha (1833 – 14 November 1913), was an Ottoman statesman and liberal pol ...

and his Foreign Minister Tevfik Pasha continued in the office. They were now independent of the Sultan and were taking measures to strengthen the Porte against the encroachments of both the Palace and the CUP. Said and Kâmil were nevertheless men of the old regime.

31 March Incident

After nine months into the new government, discontent found expression in a fundamentalist movement which attempted to dismantle Constitution and revert it with a monarchy. The

After nine months into the new government, discontent found expression in a fundamentalist movement which attempted to dismantle Constitution and revert it with a monarchy. The 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

began when Abdul Hamid promised to restore the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, eliminate secular policies, and restore the rule of Islamic law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

, as the mutinous troops claimed. CUP also eliminated the time for religious observance. Unfortunately for the advocates of representative parliamentary government, mutinous demonstrations by disenfranchised regimental officers broke out on 13 April 1909, which led to the collapse of the government. On 27 April 1909 the counter-coup was put down using the 11th Salonika Reserve Infantry Division of the Third Army. Some of the leaders of Bulgarian federalist wing like Sandanski

Sandanski ( bg, Сандански ; el, Σαντάνσκι, formerly known as Sveti Vrach, bg, Свети Врач, until 1947) is a town and a recreation centre in south-western Bulgaria, part of Blagoevgrad Province. Named after the Bulga ...

and Chernopeev participated in the march on Capital to depose the "attempt to dismantle constitution". Abdul Hamid II was removed from the throne, and Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd ( ota, محمد خامس, Meḥmed-i ḫâmis; tr, V. Mehmed or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) reigned as the 35th and penultimate Ottoman Sultan (). He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I. He succeeded his half-brother ...

became the Sultan.

On 5 August 1909, the revised constitution was granted by the new Sultan Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd ( ota, محمد خامس, Meḥmed-i ḫâmis; tr, V. Mehmed or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) reigned as the 35th and penultimate Ottoman Sultan (). He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I. He succeeded his half-brother ...

. This revised constitution, as the one before, proclaimed the equality of all subjects in the matter of taxes, military service (allowing Christians into the military for the first time), and political rights. The new constitution was perceived as a big step for the establishment of a common law for all subjects. The position of Sultan was greatly reduced to a figurehead, while still retaining some constitutional powers, such as the ability to declare war. The new constitution, aimed to bring more sovereignty to the public, could not address certain public services, such as the Ottoman public debt

The Ottoman public debt was a term which dated back to 24 August 1855,< ...

, the Ottoman Bank

The Ottoman Bank ( tr, Osmanlı Bankası), known from 1863 to 1925 as the Imperial Ottoman Bank (french: Banque Impériale Ottomane, ota, بانق عثمانی شاهانه) and correspondingly referred to by its French acronym BIO, was a bank ...

or Ottoman Public Debt Administration

The Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA) ( ota, دیون عمومیهٔ عثمانیه واردات مخصصه ادارهسی, script=Arab, Düyun-u Umumiye-i Osmaniye Varidat-ı Muhassasa İdaresi, or simply as it was popularly known), ...

because of their international character. The same held true of most of the companies which were formed to execute public works such as Baghdad Railway

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, tobacco and cigarette trades of two French companies the "Regie Company

The Ottoman Tobacco Company, also known as the Régie Company for its French official name ''Société de la régie co-intéressée des tabacs de l'empire Ottoman'', was a parastatal company or Regie formed in the later Ottoman Empire by the Ottoma ...

", and "Narquileh tobacco".

Italian War, 1911

Italy declared war, the

Italy declared war, the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

, on the Empire on 29 September 1911, demanding the turnover of Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

and Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

. Italian forces took those areas on 5 November of that year. Although minor, the war was an important precursor of World War I as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

states.

The Ottomans lost their last directly ruled African territory. The Italians also sent weapons to Montenegro, encouraged Albanian dissidents, and seized the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the disorganized Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

attacked the Empire before the war with Italy had ended.

On 18 October 1912, Italy and the Empire signed a treaty in Ouchy near Lausanne. Often called Treaty of Ouchy, but also named as the First Treaty of Lausanne.

1912 election and coup

TheFreedom and Accord Party The Freedom and Accord Party ( ota, حریت و ایتلاف فرقهسی, Hürriyet ve İtilaf Fırkası, script=Arab), also known as the Liberal Union or the Liberal Entente, was a liberal Ottoman political party active between 1911 and 1913, ...

, successor to the Liberty Party, was in power when the First Balkan War broke out in October. The Party of Union and Progress won landslide the 1912 Ottoman general election

Early general elections were held in the Ottoman Empire in April 1912. Due to electoral fraud and brutal electioneering, which earned the elections the nickname Sopalı Seçimler ("Election of Clubs"), the ruling Committee of Union and Progress won ...

. Decentralization (the Liberal Union's position) was rejected and all effort was directed toward streamline of the government, streamlining the administration (bureaucracy), and strengthening the armed forces. The CUP, which got the public mandate from the electorate, did not compromise with minority parties like their predecessors (that is being Sultan Abdul Hamid) had been. The first three years of relations between the new regime and the Great Powers were demoralizing and frustrating. The Powers refused to make any concessions over the Capitulations and loosen their grip over the Empire's internal affairs.

When the Italian War and the counterinsurgency operations in Albania and

When the Italian War and the counterinsurgency operations in Albania and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

began to fail, a number of high-ranking military officers, who were unhappy with the counterproductive political involvement in these wars, formed a political committee in the capital. Calling themselves the Savior Officers

Savior or Saviour may refer to:

*A person who helps people achieve salvation, or saves them from something

Religion

* Mahdi, the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule for seven, nine or nineteen years

* Maitreya

* Messiah, a saviour or li ...

, its members were committed to reducing the autocratic control wielded by the CUP over military operations. Supported by the Freedom and Accord in parliament, these officers threatened violent action unless their demands were met. Said Pasha resigned as Grand Vizier on 17 July 1912, and the government collapsed. A new government, so called the "Great cabinet", was formed by Ahmet Muhtar Pasha. The members of the government were prestigious statesmen, technocrat government, and they easily received the vote of confidence. The CUP excluded from cabinet posts.

The Ottoman Aviation Squadrons

The Aviation Squadrons of the Ottoman Empire were military aviation units of the Ottoman Army and Navy.Edward J. Erickson, ''Ordered To Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War'', "Appendix D The Ottoman Aviation Inspectorate an ...

established by largely under French guidance in 1912. Squadrons were established in a short time as Louis Blériot

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot ( , also , ; 1 July 1872 – 1 August 1936) was a French aviator, inventor, and engineer. He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of th ...

and the Belgian pilot Baron Pierre de Caters performed the first flight demonstration in the Empire on 2 December 1909.

Balkan Wars, 1912–1913

The three new Balkan states formed at the end of the 19th century andMontenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, sought additional territories from the Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, Macedonia, and Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

regions, behind their nationalistic arguments. The incomplete emergence of these nation-states on the fringes of the Empire during the nineteenth century set the stage for the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

. On 10 October 1912 the collective note of the powers was handed. CUP responded to demands of European powers on reforms in Macedonia on 14 October.

While the Powers were asking Empire to reform Macedonia, under the encouragement of Russia, a series of agreements were concluded: between Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

in March 1912, between Greece and Bulgaria in May 1912, and Montenegro subsequently concluded agreements between Serbia and Bulgaria respectively in October 1912. The Serbian-Bulgarian agreement specifically called for the partition of Macedonia which resulted in the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

. A nationalist uprising broke out in Albania, and on 8 October, the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

, consisting of Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria, mounted a joint attack on the Empire, starting the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

. The strong march of the Bulgarian forces in Thrace pushed the Ottoman armies to the gates of Constantinople. The Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

soon followed. Albania declared independence on 28 November.

The empire agreed to a ceasefire on 2 December, and its territory losses were finalized in 1913 in the treaties of

The empire agreed to a ceasefire on 2 December, and its territory losses were finalized in 1913 in the treaties of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

. Albania became independent, and the Empire lost almost all of its European territory (Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

, Sanjak of Novi Pazar

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Novopazarski sandžak, Новопазарски санџак; tr, Yeni Pazar sancağı) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and ...

, Macedonia and western Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

) to the four allies. These treaties resulted in the loss of 83 percent of their European territory and almost 70 percent of their European population.

Inter-communal conflicts, 1911–1913

In the two-year period between September 1911 and September 1913 ethnic cleansing sent hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees, ormuhacir

Muhacir or Muhajir (from ar, مهاجر, translit=muhājir, lit=migrant) are the estimated 10 million Ottoman Muslim citizens, and their descendants born after the onset of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, mostly Turks but also Albanians, ...

, streaming into the Empire, adding yet another economic burden and straining the social fabric. During the wars, food shortages and hundreds of thousands of refugees haunted the empire. After the war there was a violent expulsion of the Muslim peasants of eastern Thrace.

Cession of Kuwait and Albania, 1913

TheAnglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913

The Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, also known as the "Blue Line", was an agreement between the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire and the Government of the United Kingdom which defined the limits of Ottoman jurisdiction in the area of the P ...

was a short-lived agreement signed in July 1913 between the Ottoman sultan Mehmed V and the British over several issues. However the status of Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

that came to be the only lasting result, as its outcome was formal independence for Kuwait.

Albania had been under Ottoman rule since about 1478. When Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece laid claim to Albanian-populated lands during Balkan Wars, the Albanians declared independence. The European Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

endorsed an independent Albania in 1913, after the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

leaving outside the Albanian border more than half of the Albanian population and their lands, that were partitioned between Montenegro, Serbia and Greece. They were assisted by Aubrey Herbert

Colonel The Honourable Aubrey Nigel Henry Molyneux Herbert (3 April 1880 – 26 September 1923), of Pixton Park in Somerset and of Teversal, in Nottinghamshire, was a British soldier, diplomat, traveller, and intelligence officer associated ...

, a British MP who passionately advocated their cause in London. As a result, Herbert was offered the crown of Albania, but was dissuaded by the British prime minister, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, from accepting. Instead the offer went to William of Wied

Prince Wilhelm of Wied (German: ''Wilhelm Friedrich Heinrich Prinz zu Wied'', 26 March 1876 – 18 April 1945), reigned briefly as sovereign of the Principality of Albania as Vilhelm I from 7 March to 3 September 1914, when he left for exile. Hi ...

, a German prince who accepted and became sovereign of the new Principality of Albania

The Principality of Albania ( al, Principata e Shqipërisë or ) refers to the short-lived monarchy in Albania, headed by Wilhelm, Prince of Albania, that lasted from the Treaty of London of 1913 which ended the First Balkan War, through ...

. Albania's neighbours still cast covetous eyes on this new and largely Islamic state. The young state, however, collapsed within weeks of the outbreak of World War I.

Union and Progress takes control (1913–1918)

At the turn of 1913, theOttoman Modern Army

Ottoman is the Turkish spelling of the Arabic masculine given name Uthman ( ar, عُثْمان, ‘uthmān). It may refer to:

Governments and dynasties

* Ottoman Caliphate, an Islamic caliphate from 1517 to 1924

* Ottoman Empire, in existence fro ...

failed at counterinsurgencies in the periphery of the empire, Libya was lost to Italy, and Balkan war erupted in the fall of 1912. Freedom and Accord flexed its muscles with the forced dissolution of the parliament in 1912. The signs of humiliation of the Balkan wars worked to the advantage of the CUP The cumulative defeats of 1912 enabled the CUP to seize control of the government.

The Freedom and Accord Party presented the peace proposal to the Ottoman government as a collective démarche, which was almost immediately accepted by both the Ottoman cabinet and by an overwhelming majority of the parliament on 22 January 1913. The 1913 Ottoman coup d'état

The 1913 Ottoman coup d'état (January 23, 1913), also known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte ( tr, Bâb-ı Âlî Baskını), was a coup d'état carried out in the Ottoman Empire by a number of Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) members led by ...

(23 January), was carried out by a number of CUP members led by Ismail Enver

İsmail Enver, better known as Enver Pasha ( ota, اسماعیل انور پاشا; tr, İsmail Enver Paşa; 22 November 1881 – 4 August 1922) was an Ottoman military officer, revolutionary, and convicted war criminal who formed one-third ...

and Mehmed Talaat, in which the group made a surprise raid on the central Ottoman government buildings, the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The nam ...

( tr, links=no, Bâb-ı Âlî). During the coup, the Minister of the Navy Nazım Pasha

Hüseyin Nazım Pasha ( tr, Hüseyin Nâzım Paşa; 1848 – 23 January 1913) was an Ottoman general, who was the Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Army during the First Balkan War of 1912–13. He was murdered by Yakub Cemil during the 1913 O ...

was assassinated and the Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

, Kâmil Pasha

Mehmed Kâmil Pasha ( ota, محمد كامل پاشا مصري زاده; tr, Kıbrıslı Mehmet Kâmil Paşa, "Mehmed Kamil Pasha the Cypriot"), also spelled as Kiamil Pasha (1833 – 14 November 1913), was an Ottoman statesman and liberal pol ...

, was forced to resign. The CUP established tighter control over the faltering Ottoman state. The new grand vizier Mahmud Sevket Pasha

Mahmud Shevket Pasha ( ota, محمود شوكت پاشا, 1856 – 11 June 1913)David Kenneth Fieldhouse: ''Western imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958''. Oxford University Press, 2006 p.17 was an Ottoman generalissimo and statesman, wh ...

was assassinated by Freedom and Accord supporters just in 5 months after the coup in June 1913. Cemal Pasha's posting as commendante of Constantinople put the party underground. The execution of former officials had been an exception since the Tanzimat (1840s) period; punishment was usually exile. The public life could not be far more brutish 75 years after the Tanzimat. The Foreign Ministry was always occupied by someone from the inner circle of the CUP except for the interim appointment of Muhtar Bey. Said Halim Pasha

Mehmed Said Halim Pasha ( ota, سعيد حليم پاشا ; tr, Sait Halim Paşa; 18 or 28 January 1865 or 19 February 1864 – 6 December 1921) was an Ottoman statesman of Albanian originDanişmend (1971), p. 102 who served as Grand Vizier of ...

who was already Foreign Minister, became Grand Vizier in June 1913 and remained in office until October 1915. He was succeeded in the Ministry by Halil Menteşe

Halil Menteşe (1874–1948) was a Turkish government minister and politician, who was a well known official of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). He was the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the President of the Chamber of Deputies in the ...

.

In May 1913 a German military mission assigned

In May 1913 a German military mission assigned Otto Liman von Sanders

Otto Viktor Karl Liman von Sanders (; 17 February 1855 – 22 August 1929) was an Imperial German Army general who served as a military adviser to the Ottoman Army during the First World War. In 1918 he commanded an Ottoman army during the Sin ...

to help train and reorganize the Ottoman army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

. Otto Liman von Sanders was assigned to reorganize the First Army, his model to be replicated to other units; as an advisor e took the command of this army in November 1914

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plura ...

and began working on its operational area which was the straits. This became a scandal and intolerable for St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. The Russian Empire developed a plan for invading and occupying the Black Sea port of Trabzon

Trabzon (; Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (''Trapezous''), Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (''Trapezounta''); Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (''Trapizoni'')), historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the Bl ...

or the Eastern Anatolian town of Bayezid in retaliation. To solve this issue Germany demoted Otto Liman von Sanders to a rank with which he could barely command an army corps. If there was no solution through Naval occupation of Constantinople, the next Russian idea was to improve the Russian Caucasus Army.

Elections, 1914

The Empire lost territory in the Balkans, where many of its Christian voters were based before the 1914 elections. The CUP made efforts to win support in the Arab provinces by making conciliatory gestures to Arab leaders. Weakened Arab support for Freedom and Accord enabled the CUP to call elections with unionists holding the upper hand. After 1914 elections, the democratic structure had a better representation in the parliament; the parliament that emerged from the elections in 1914 reflected better ethnic composition of the Ottoman population. There were more Arab deputies, which were under-represented in previous parliaments. The CUP had a majority government. Ismail Enver became a Pasha and was assigned as theMinister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

; Ahmet Cemal who was the military governor of Constantinople became Minister of the Navy Minister of the Navy may refer to:

* Minister of the Navy (France)

* Minister of the Navy (Italy)

The Italian Minister of the Navy ( it, Ministri della Marina del Regno) was a member in the Council Ministers until 1947, when the ministry merged ...

; and once the postal official Talaat became the Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

. These Three Pashas

The Three Pashas also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha (1874–1921), the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War; ...

would maintain ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' control of the Empire as a military regime and almost as a personal dictatorship under Talaat Pasha during the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Until the 1919 Ottoman general election

General elections were held in the Ottoman Empire in 1919 and were the last official elections held in the Empire.Hasan Kayalı (1995"Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919"''International Journal of Middle East Stud ...

, any other input into the political process was restricted with the outbreak of the World War I.

Local-Regional politics

Albanian politics

The Albanians of

The Albanians of Tirana

Tirana ( , ; aln, Tirona) is the capital and largest city of Albania. It is located in the centre of the country, enclosed by mountains and hills with Dajti rising to the east and a slight valley to the northwest overlooking the Adriatic Sea ...

and Elbassan

Elbasan ( ; sq-definite, Elbasani ) is the fourth most populous city of Albania and seat of Elbasan County and Elbasan Municipality. It lies to the north of the river Shkumbin between the Skanderbeg Mountains and the Myzeqe Plain in central A ...

, where the Albanian National Awakening

The Albanian National Awakening ( sq, Rilindja or ), commonly known as the Albanian Renaissance or Albanian Revival, is a period throughout the 19th and 20th century of a cultural, political and social movement in the Albanian history where the ...

spread, were among the first groups to join the constitutional movement, hoping that it would gain their people autonomy within the empire. However, due to shifting national borders in the Balkans, the Albanians had been marginalized as a nation-less people. The most significant factor uniting the Albanians, their spoken language, lacked a standard literary form and even a standard alphabet. Under the new regime the Ottoman ban on Albanian-language schools and on writing the Albanian language lifted. The new regime also appealed for Islamic solidarity to break the Albanians' unity and used the Muslim clergy to try to impose the Arabic alphabet. The Albanians refused to submit to the campaign to "Ottomanize" them by force. As a consequence, Albanian intellectuals meeting, the Congress of Manastir

The Congress of Manastir ( sq, Kongresi i Manastirit) was an academic conference held in the city of Manastir (now Bitola) from November 14 to 22, 1908, with the goal of standardizing the Albanian alphabet. November 22 is now a commemorative da ...

on 22 November 1908, chose the Latin alphabet as a standard script.

= Arab politics

= TheHauran Druze Rebellion

The Hauran Druze Rebellion was a violent Druze uprising against Ottoman authority in the Syrian province, which erupted in 1909. The rebellion was led by the al-Atrash family, in an aim to gain independence, but ended in brutal suppression of th ...

was a violent Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

uprising in the Syrian province, which erupted in 1909. The rebellion was led by the al-Atrash family, in an aim to gain independence. A business dispute between Druze chief Yahia bey Atrash in the village of Basr al-Harir escalated into a clash of arms between the Druze and Ottoman-backed local villagers. Though it is the financial change during second constitutional area; the spread of taxation, elections and conscription, to areas already undergoing economic change caused by the construction of new railroads, provoked large revolts, particularly among the Druzes and the Hauran. Sami Pasha al-Farouqi arrived in Damascus in August 1910, leading an Ottoman expeditionary force of some 35 battalions. The resistance collapsed.

In 1911, Muslim intellectuals and politicians formed " The Young Arab Society", a small Arab nationalist club, in Paris. Its stated aim was "raising the level of the Arab nation to the level of modern nations." In the first few years of its existence, al-Fatat called for greater autonomy within a unified Ottoman state rather than Arab independence from the empire. Al-Fatat hosted the Arab Congress of 1913

The Arab Congress of 1913 (also known as the "Arab National Congress," "First Palestinian Conference," the "First Arab Congress," and the "Arab-Syrian Congress") met in a hall of the French Geographical Society (Société de Géographie) at 184 Bo ...

in Paris, the purpose of which was to discuss desired reforms with other dissenting individuals from the Arab world. They also requested that Arab conscripts to the Ottoman army not be required to serve in non-Arab regions except in time of war. However, as the Ottoman authorities cracked down on the organization's activities and members, al-Fatat went underground and demanded the complete independence and unity of the Arab provinces.Choueiri, pp.166–168.

Nationalist movement become prominent during this Ottoman period, but it has to be mentioned that this was among Arab nobles and common Arabs considered themselves loyal subjects of the Caliph.Karsh, ''Islamic Imperialism'' Instead of Ottoman Caliph, the British, for their part, incited the Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, شريف مكة, Sharīf Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, شريف الحجاز, Sharīf al-Ḥijāz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

to launch the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

during the First World War.

= Armenian politics

= In 1908, the

In 1908, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

(ARF) or Dashnak Party embraced a public position endorsing participation and reconciliation in the Imperial Government

The name imperial government (german: Reichsregiment) denotes two organs, created in 1500 and 1521, in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation to enable a unified political leadership, with input from the Princes. Both were composed of the em ...

of the Ottoman Empire and the abandonment of the idea of an independent Armenia. Stepan Zorian

Stepan Zorian (Armenian: Ստեփան Զօրեան, 1867–1919), better known by his ''nom de guerre'' Rostom (), was one of the three founders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and a leader of the Armenian national liberation movement.

...

and Simon Zavarian

Simon Zavarian (Armenian: , also known by his ''nom de guerre'' Anton, ; 1866 – 1913) was a leader of the Armenian national liberation movement and one of the three founders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, along with Kristapor Mikaeli ...

managed the political campaign for the 1908 Ottoman Elections. ARF field workers were dispatched to the provinces containing significant Armenian populations; for example, Drastamat Kanayan

Drastamat Kanayan (; 31 May 1884 8 March 1956), better known as Dro (Դրօ), was an Armenian military commander and politician. He was a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. He briefly served as Defence Minister of the First Republic ...

(Dro), went to Diyarbakir as a political organizer. The Committee of Union and Progress could only able to bring 10 Armenian representatives to the 288 seats in the 1908 election. The other 4 Armenians represented parties with no ethnic affiliation. The ARF was aware that the elections were shaky ground and maintained its political direction and self-defence mechanism intact and continued to smuggle arms and ammunition.

On 13 April 1909, while Constantinople was dealing with the consequences of 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

, an outbreak of violence, known today as the Adana Massacre, shook in April the ARF-CUP relations to the core. On 24 April the 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

and suppression of the Adana violence followed each other. The Ottoman authorities in Adana brought in military forces and ruthlessly stamped out both real opponents, while at the same time massacring thousands of innocent people. In July 1909, the CUP government announced the trials of various local government and military officials, for "being implicated in the Armenian massacres.".

On 15 January 1912, the Ottoman parliament dissolved and political campaigns began almost immediately. After the election, on 5 May 1912, Dashnak officially severed the relations with the Ottoman government; a public declaration of the Western Bureau printed in the official announcement was directed to "Ottoman Citizens." The June issue of