Cold War In Asia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cold War in Asia was a major dimension of the world-wide

Beijing was very pleased that the success of the Soviet Union in the

Beijing was very pleased that the success of the Soviet Union in the

online

/ref> The Kremlin never realized the dangers involved and did not have even a basic understanding of the forces they confronted. According to Leninist principles, Afghanistan was not ready for revolution in the first place. Furthermore, intervention would destroy détente with the United States and Western Europe. Factions within the Afghan People's Democratic Party (Communist) government that were hostile to Soviet interests gained ascendancy and raised the specter of an independently minded Communist state located on the southern border that might cause future trouble inside the Muslim parts of the USSR. At this point Moscow decided not to send troops but instead stepped up shipments of military equipment such as artillery, armored personnel carriers and 48,000 machine guns; they also sent 100,000 tons of wheat. Moscow's first man in Kabul was prime minister

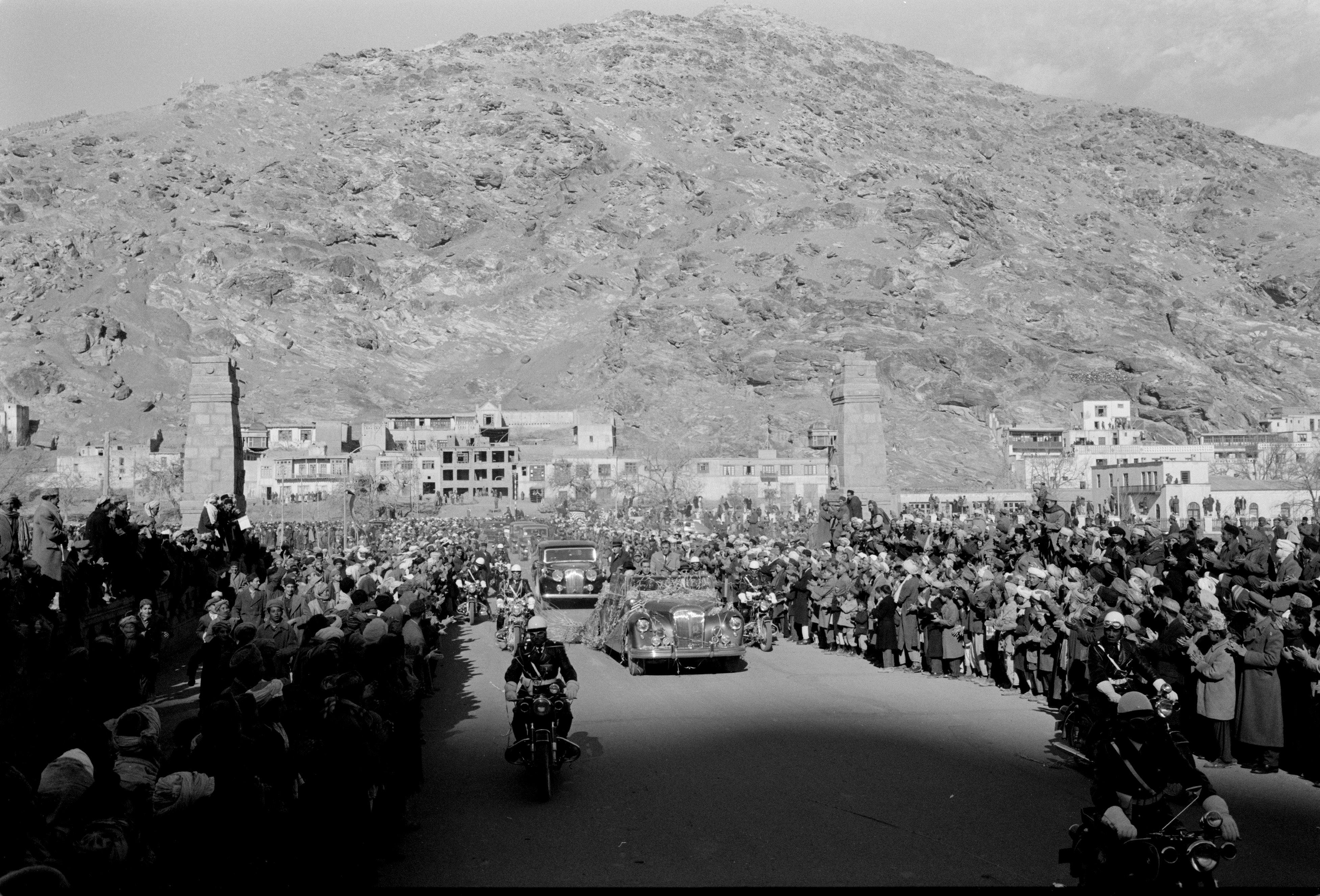

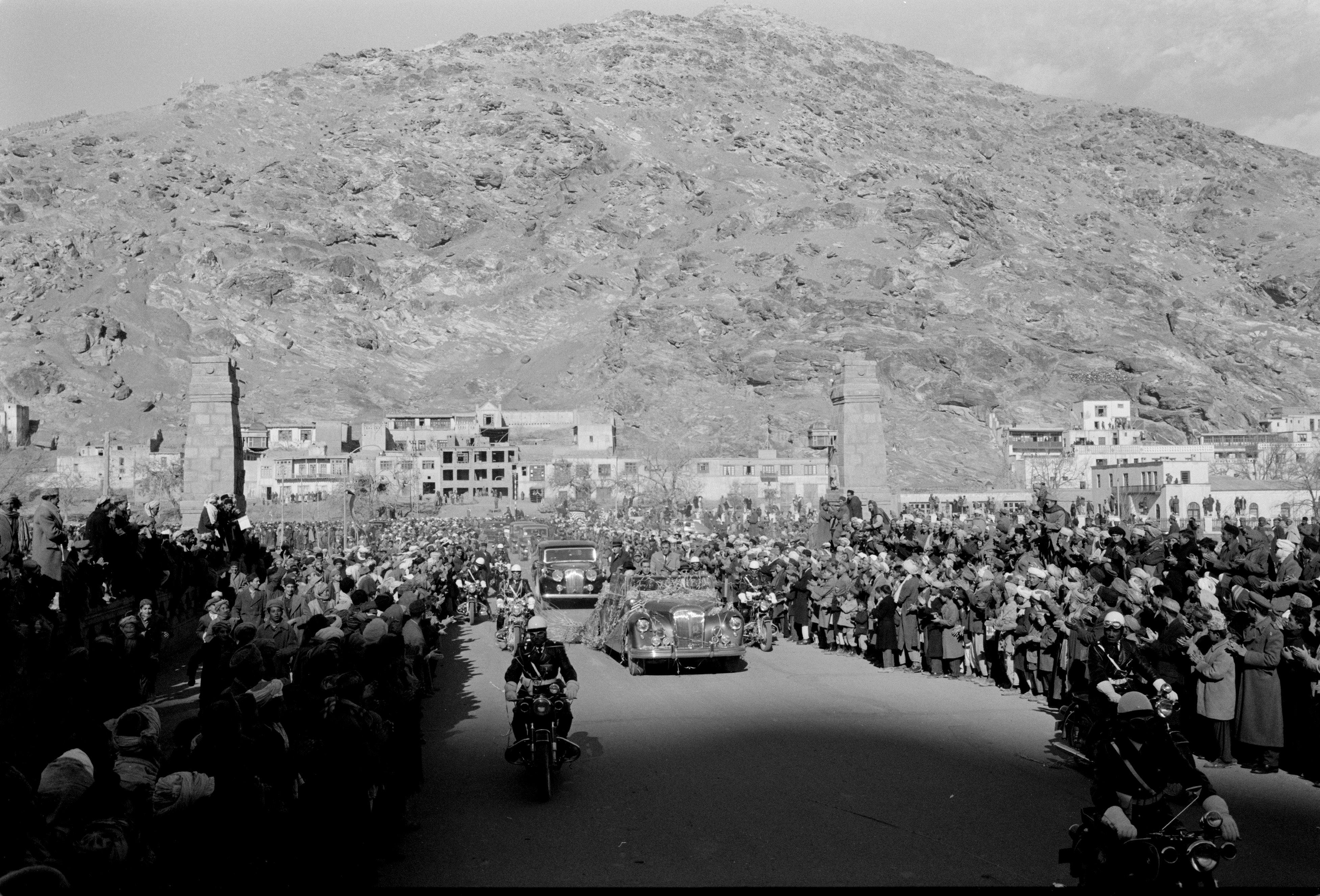

Eisenhower declined Afghanistan's request for defense cooperation but extended an economic assistance program focused on the development of Afghanistan's physical infrastructure—roads, dams, and power plants. Later, American aid shifted from infrastructure projects to technical assistance programs to help develop the skills needed to build a modern economy. Contacts between the United States and Afghanistan increased during the 1950s to counter the attraction of communism. After Eisenhower made a state visit to Afghanistan in December 1959 Washington grew confident that Afghanistan was safe from ever becoming a Soviet

Eisenhower declined Afghanistan's request for defense cooperation but extended an economic assistance program focused on the development of Afghanistan's physical infrastructure—roads, dams, and power plants. Later, American aid shifted from infrastructure projects to technical assistance programs to help develop the skills needed to build a modern economy. Contacts between the United States and Afghanistan increased during the 1950s to counter the attraction of communism. After Eisenhower made a state visit to Afghanistan in December 1959 Washington grew confident that Afghanistan was safe from ever becoming a Soviet

online

/ref>

online

* Bajpai, Kanti, Selina Ho, and Manjari Chatterjee Miller, eds. ''Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations'' (Routledge, 2020)

excerpt

* Bhagavan, Manu, ed. ''India and the Cold War'' (2019

excerpt

* Brazinsky, Gregg. "The Birth of a Rivalry: Sino-American Relations During the Truman Administration" in Daniel S. Margolies, ed. ''A Companion to Harry S. Truman'' (2012) pp 484–497; emphasis on historiography. * Brazinsky, Gregg A. ''Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2017)

four online reviews & author response

* Brimmell, J. H. ''Communism in South East Asia : a political analysis.'' (Oxford UP, 1959

online

* Brown, Archie. ''The rise and fall of communism'' (Random House, 2009). pp 179–193, 313–359

online

* Brune, Lester, and Richard Dean Burns. '' Chronology of the Cold War: 1917–1992'' (2005), 720 p

online

* Choudhury, G.W. ''India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Major Powers: Politics of a Divided Subcontinent'' (1975), relations with US, USSR and China. * Fawcett, Louise, ed. ''International relations of the Middle East'' (3rd ed. Oxford UP, 2016

full text online

* Friedman, Jeremy. ''Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World'' (2018

excerpt

* Fürst, Juliane, Silvio Pons and Mark Selden, eds. ''The Cambridge History of Communism (Volume 3): Endgames?.Late Communism in Global Perspective, 1968 to the Present'' (2017

excerpt

* Garver, John W. ''China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic'' (Oxford UP, 2016

excerpt

* Goscha, Christopher, and Christian Ostermann, eds. ''Connecting Histories: Decolonization and the Cold War in Southeast Asia (1945-1962)'' (Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2009) * Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi, ed. ''The Cold War in East Asia, 1945–1991'' (Stanford UP, 2011) From the Cold War International History Projec

online outline

* Hilger, Andreas. "The Soviet Union and India: the Khrushchev era and its aftermath until 1966." (2009

online

* Hilali, A. Z. "Cold war politics of superpowers in South Asia." ''The Dialogue'' 1.2 (2006): 68–108

online

* Hiro, Dilip. ''Cold War In The Islamic World: Saudi Arabia, Iran And The Struggle For Supremacy.'' (2019

excerpt

* Judge, Edward H. and John W. Langdon. ''The Struggle against Imperialism: Anticolonialism and the Cold War'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), pp 37–99. Brief overview by experts. * Kennedy, Malcolm D. ''A Short History of Communism in Asia'' (1957

online

* King, Amy. ''China-Japan Relations after World War Two: Empire, Industry and War, 1949–1971'' (Cambridge UP, 2016). * Lawrence, Mark Atwood. "Setting the Pattern: The Truman Administration and Southeast Asia" in Daniel S. Margolies, ed. ''A Companion to Harry S. Truman'' (2012) pp 532–552; emphasis on historiography * Lesch, David W. and Mark L. Haas, eds. ''The Middle East and the United States: History, Politics, and Ideologies'' (6th ed, 2018

excerpt

* Li, Xiaobing. ''The Cold War in East Asia'' (Routledge, 2018

excerpt

* Li, Xiaobing, and Hongshan Li, eds. ''China and the United States: A New Cold War History'' (University Press of America, 1998

excerpt

* * Lüthi, Lorenz M. ''Cold Wars: Asia, the Middle East, Europe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2020) 774pp * Lüthi, Lorenz M. ''The Sino Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World'' (2007). * Malone, David M. et al. eds. ''Oxford Handbook of Indian Foreign Policy '' (2015) * Matray, James, ed. ''East Asia and the United States: An Encyclopedia of Relations Since 1784'' (2 vol. 2002) * Matray, James I. "Conflicts in Korea" in Daniel S. Margolies, ed. ''A Companion to Harry S. Truman'' (2012) pp 498–531; emphasis on historiography. * May, Ernest R. ed. ''The Truman Administration and China 1945–1949'' (1975) summary plus primary sources

online

* Naimark, Norman Silvio Pons and Sophie Quinn-Judge, eds. ''The Cambridge History of Communism (Volume 2): The Socialist Camp and World Power, 1941-1960s'' (2017

excerpt

* Phuangkasem, Corrine. ''Thailand's Foreign Relations: 1964-80'' (Brookfield, 1984). * Pons, Silvio, and Robert Service, eds. ''A Dictionary of 20th-Century Communism'' (2010). * * Priestland, David. ''The Red Flag: A History of Communism'' (Grove, 2009). * Rajan, Nithya. "‘No Afghan Refugees in India’: Refugees and Cold War Politics in the 1980s." ''South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies'' 44.5 (2021): 851-867. * Sattar, Abdul. ''Pakistan's Foreign Policy, 1947-2012: A Concise History'' (3rd ed. Oxford UP, 2013)

online 2nd 2009 edition

* Tucker, Spencer, et al. eds. ''The Encyclopedia of the Cold War: A Political, Social, and Military History'' (5 vol., 2007) 1969pp * Westad, Odd Arne. ''Brothers in arms: the rise and fall of the Sino-Soviet alliance, 1945-1963'' (Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1998) * Westad, Odd Arne. ''The global Cold War: Third World interventions and the making of our times'' (Cambridge UP, 2005). * * Yahuda, Michael. ''The international politics of the Asia-Pacific : 1945-1995'' (1st ed. 1996

online

online

* Davis, Simon, and Joseph Smith. ''The A to Z of the Cold War'' (Scarecrow, 2005), encyclopedia focused on military aspects * Haruki, Wada. ''The Korean War: An International History'' (2014

excerpt

* House, Jonathan. ''A Military History of the Cold War, 1944–1962'' (2012), emphasis on small wars * Kislenko, Arne. "The Vietnam War, Thailand, and the United States" in Richard Jensen et al. eds. ''Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century'' (Praeger, 2003) pp 217–245. * Lawrence, Mark Atwood, and Fredrik Logevall, eds. ''The First Vietnam War: Colonial Conflict and Cold War Crisis'' (2007) * Li, Xiaobing. ''China at War: An Encyclopedia'' (ABC-CLIO, 2012)

excerpt

* McMahon, Robert J. ''Major problems in the history of the Vietnam War: documents and essays'' (2nd ed 1995

online

* Miller, David. ''The Cold War: A Military History'' (Macmillan, 2015)

excerpt

NATO and Warsaw war plans; little action * Olson, James Stuart, ed. ''The Vietnam War: Handbook of the literature and research'' (Greenwood, 1993

excerpt

historiography * Roberts, Priscilla. ''Behind the Bamboo Curtain: China, Vietnam, and the Cold War'' (2006) * Smith, R.B. '' An International History of the Vietnam War'' (2 vol 1985) * Zhai, Qiang. ''China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950-1975'' (2000)

vol 2 online

* Judge, Edward H. and John W. Langdon, eds. ''The Cold War through Global Documents'' (3rd ed. 2018), includes primary sources. * Lawrence, Mark Atwood, ed. ''The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents'' (2014) *. *.

"China-Southeast Asia Relations" from Wilson Center

US State Department Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs

US State Department Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs

US State Department Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs

{{Cold War 20th-century conflicts Wars involving the Soviet Union Wars involving the United States Wars involving China Soviet Union–United States relations China–United States relations Cold War by continent

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

that shaped largely diplomacy and warfare from the mid-1940s to 1991. The main players were the United States, the Soviet Union, China, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

(Republic of China), North Korea, South Korea, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Other countries were also involved, and less directly so was the Middle East. In the late 1950s division between China and the Soviet Union began to emerge, culminating in the Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

, and the two fought for control of Communist movements across the world, especially in Asia.

China

Relations with United States

American images of China

Harold Isaacs

Harold Robert Isaacs (1910–1986) was an American journalist and political scientist.

Career

Isaacs graduated from Columbia University in 1929, then briefly worked as a reporter for the ''New York Times.'' He went to China in 1930 with no st ...

published ''Scratches on our Minds: American Images of China and India'' in 1955. By reviewing the popular and scholarly literature on Asia that appeared in the United States and by interviewing many American experts, Isaacs identified six stages of American attitudes toward China. They were "respect" (18th century), "contempt" (1840–1905), "benevolence" (1905 to 1937), "admiration" (1937–1944); "disenchantment" (1944–1949), and "hostility" (after 1949). In 1990, historian Jonathan Spence updated Isaac's model to include "reawakened curiosity" (1970–1974); "guileless fascination" (1974–1979), and "renewed skepticism" (1980s).

Political scientist Peter Rudolf in 2020 argued that Americans see China as a threat to the established order in its drive for regional hegemony in East Asia now, and a future aspirant for global supremacy. Beijing rejects these notions, but continues its assertive policies and its quest for allies.

Korean War 1950–1953

The Korean War began at the end of June 1950 when North Korea, a Communist country, invaded South Korea, which was under U.S. protection. Without consulting Congress, President Harry S Truman ordered GeneralDouglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

to use all American forces to resist the invasion. Truman then received approval from the United Nations, which the Soviets were boycotting. UN forces managed to cling to a toehold in Korea, as the North Koreans outran their supply system. MacArthur's counterattack at Inchon destroyed the invasion army, and the UN forces captured most of North Korea on their way to the Yalu River, Korea's northern border with China. President Truman had decided—and the UN agreed—to reunify all of Korea. UN forces were poised to decisively defeat the North Korean invaders.

In October 1950, China intervened unexpectedly, driving the UN forces all the way back to South Korea. Mao Zedong felt threatened by the United Nations advance. Although technically far inferior, his army had much larger manpower resources and was just across Korea's northern border at the Yalu River. The fighting stabilized close to the original 38th parallel that had divided North and South. UN-US commanding general Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

wanted to continue the rollback strategy of unifying Korea but Truman changed and instead switched to a policy of containment that would allow North Korea to persist. Truman's dismissal of MacArthur in April 1951 sparked an intense debate on American Far Eastern Cold War policy. Truman took the blame for a high-cost stalemate with 37,000 Americans killed and over 100,000 wounded. Peace talks bogged down over the question of repatriating prisoners who did not want to return to Communism. President Eisenhower broke the impasse by warning he might use nuclear weapons, and an armistice was reach that has remained in effect ever since, with large American forces still stationed in South Korea as a tripwire.

Split with USSR

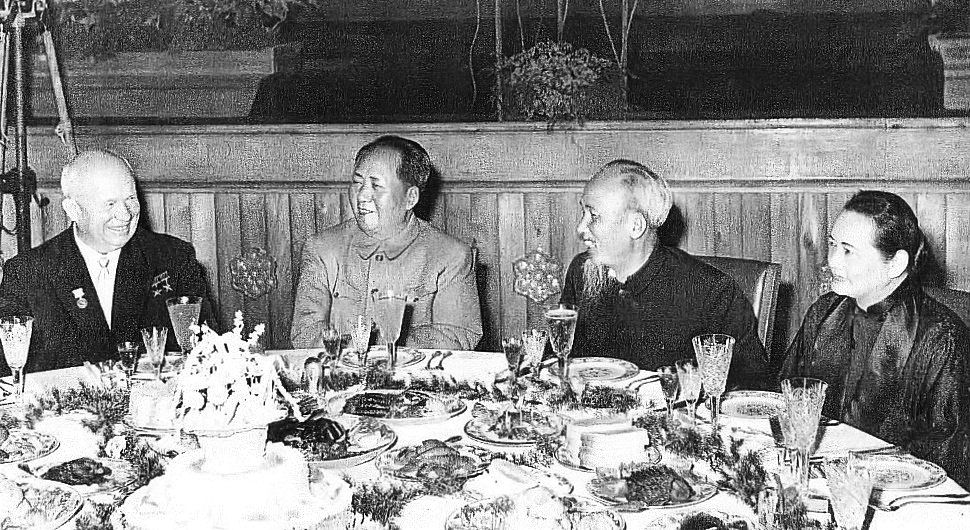

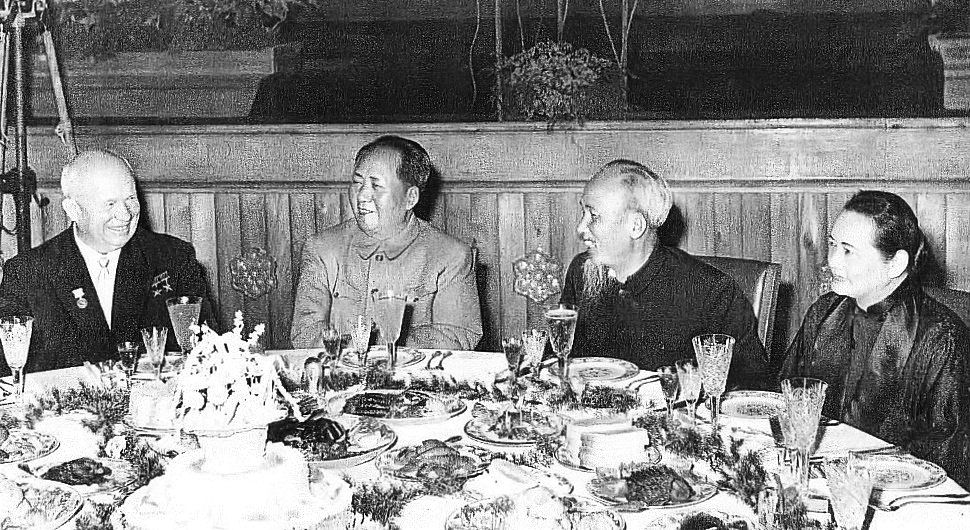

Beijing was very pleased that the success of the Soviet Union in the

Beijing was very pleased that the success of the Soviet Union in the space race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

– the original Sputniks – demonstrated that the international communist movement had caught up in high technology with the Americans. Mao assumed that the Soviets now had a military advantage and should step up the Cold War; Khrushchev knew that the Americans were well ahead in military uses of space. The strains multiplied, quickly making a dead letter of the 1950 alliance, destroying the socialist camp unity, and affected the world balance of power. The split started with Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

De-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

program. It angered Mao, who admired Stalin. Moscow and Beijing became worldwide rivals, forced communist parties around the world to take sides; many of them split, so that the pro-Soviet communists were battling the pro-Chinese communists for local control of the left-wing forces in much of the world.

Internally, the Sino-Soviet split encouraged Mao to plunge China into the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

, to expunge traces of Russian ways of thinking. Mao argued that as far as all-out nuclear war was concerned, the human race would not be destroyed, and instead a brave new communist world would arise from the ashes of imperialism. This attitude troubled Moscow, which had a more realistic view of the utter disasters that would accompany a nuclear war. Three major issues suddenly became critical in dividing the two nations: Taiwan, India, and China's Great Leap Forward. Although Moscow supported Beijing's position that Taiwan entirely belong to China, it demanded that it be forewarned of any invasion or serious threat that would bring American intervention. Beijing refused, and the Chinese bombardment of the island of Quemoy

Kinmen, alternatively known as Quemoy, is a group of islands governed as a county by the Republic of China (Taiwan), off the southeastern coast of mainland China. It lies roughly east of the city of Xiamen in Fujian, from which it is separate ...

in August 1958 escalated the tensions. Moscow was cultivating India, both as a major purchaser of Russian munitions, and a strategically critical ally. However China was escalating its threats to the northern fringes of India, especially from Tibet. It was building a militarily significant road system that would reach disputed areas along the border. The Russians clearly favored India, and Beijing reacted as a betrayal. By far the major ideological issue was the Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstruc ...

, which represented a Chinese rejection of the Soviet form of economic development. Moscow was deeply resentful, especially since it had spent heavily to supply China with high-technology—including some nuclear skills. Moscow withdrew its vitally needed technicians and economic and military aid. Khrushchev was increasingly crude and intemperate ridiculing China and Mao Zedong to both communist and international audiences. Beijing responded through its official propaganda network of rejecting Moscow's claim to Lenin's heritage. Beijing insisted it was the true inheritor of the great Leninist tradition. At one major meeting of communist parties, Khrushchev personally attacked Mao as an ultra leftist — a left revisionist — and compared him to Stalin for dangerous egotism. The conflict was now out of control, and was increasingly fought out in 81 communist parties around the world. The final split came in July 1963, after 50,000 refugees escaped from Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

in western China

Western China (, or rarely ) is the west of China. In the definition of the Chinese government, Western China covers one municipality ( Chongqing), six provinces (Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Qinghai), and three autonomous re ...

to Soviet territory to escape persecution. China ridiculed the Russian incompetence in the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

of 1962 as adventurism to start with and capitulationism to wind up on the losing side. Moscow now was increasingly giving priority to friendly relationships and test ban treaties with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.

Increasingly, Beijing began to consider the Soviet Union, which it viewed as Social imperialism

As a political term, social imperialism is the political ideology of people, parties, or nations that are, according to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds". In academic use, it refers to governments that enga ...

, as the greatest threat it faced, more so than even the leading capitalist power, the United States. In turn, overtures were made between the PRC and the United States, such as in the Ping Pong Diplomacy

Ping-pong diplomacy ( ''Pīngpāng wàijiāo'') refers to the exchange of table tennis (ping-pong) players between the United States (US) and People's Republic of China (PRC) in the early 1970s, that began during the 1971 World Table Tennis Cha ...

, Panda Diplomacy

Panda diplomacy is the practice of sending giant pandas from China to other countries as a tool of diplomacy. From 1941 to 1984, China gifted pandas to other countries. After a change in policy in 1984, pandas were leased instead of gifted.

Im ...

and the 1972 Nixon visit to China

The 1972 visit by United States President Richard Nixon to the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an important strategic and diplomatic overture that marked the culmination of the Nixon administration's resumption of harmonious relations betwe ...

.

Crisis in 1965

Despite Chinese ambitions, the growing opposition of the United States and of Russia became more formidable, especially in 1965 when the United States launched a massive escalation of its commitment to defending South Vietnam. Furthermore, Washington decided that China was its greatest enemy, more so than the USSR. In response to growing Chinese activity, the non-aligned powers of India and Yugoslavia moved a bit closer to the Soviet Union. Key regional leaders whom China was endorsing were overthrown or pushed back in 1965.Ben Bella

Ahmed Ben Bella ( ar, أحمد بن بلّة '; 25 December 1916 – 11 April 2012) was an Algerian politician, soldier and socialist revolutionary who served as the head of government of Algeria from 27 September 1962 to 15 September 1963 ...

was overthrown in Algeria, with a result that the Soviets gained influence in North Africa and the Middle East. Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

, the most prominent leader of sub-Saharan Africa, was deposed while on a trip to China in early 1966. The new rulers shifted Ghana to the West's side of the Cold War. Mao's efforts to regain prestige by holding a Bandung-like conference was unsuccessful. In October, 1965, came the most disastrous blow to China in the entire Cold war era. The Indonesian army broke with President Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

and systematically destroyed the Chinese-oriented PKI Communist party of Indonesia. The army and local Islamic groups killed hundreds of thousands of PKI supporters, and drove many Chinese out of Indonesia. Sukarno remained as a figurehead president but power went to General Suharto

Suharto (; ; 8 June 1921 – 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian army officer and politician, who served as the second and the longest serving president of Indonesia. Widely regarded as a military dictator by international observers, Suharto ...

, a committed enemy of communism.

Southeast Asia

Vietnam

Eisenhower and Vietnam

After the end of World War II, the CommunistViệt Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

launched an insurrection against the French colony the State of Vietnam. Seeking to bolster a NATO ally and prevent the fall of Vietnam to Communism, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations financed military operations in Vietnam by its NATO ally. In 1954, the French army was trapped near the Chinese border at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Eisenhower rejected American military intervention and the French army surrendered. A new left-wing French government met the Communists at the Geneva Conference. Moscow forced the Viet Minh to accept partition: the country was divided into a Communist North Vietnam (under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as Prime ...

) and a Capitalist South Vietnam, under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem

Ngô Đình Diệm ( or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician. He was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955), and then served as the first president of South Vietnam (Republic o ...

and his Catholic coalition.

On April 5, 1954, Eisenhower argued the domino principle, which became a staple of American strategy. He said the loss of Indochina would set off toppling dominoes, putting at risk Thailand, Malaya, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines. To prevent that the United States and seven other countries created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

(SEATO), comprising Australia, France, New Zealand, Pakistan, The Philippines, Thailand, the United Kingdom and the United States. It was a defensive alliance to prevent the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were not members; none of the members faced a serious Communist threat. Historian David L. Anderson states:Prepared neither to retreat nor fight, the Eisenhower administration turned to nation building. With profuse American military and economic aid, Diem managed to bring a degree of order to the South, reorganize the Army, and initiate some governmental programs. Washington chose to label Diem a “miracle man".... y 1960 Eisenhowerbelieved that Diem was successfully governing his nation and thereby waging the frontline fight against communist expansion at little relative cost to the United States.

Kennedy and Vietnam

Senator John F. Kennedy in 1956, publicly advocated for greater U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Eisenhower advised him in 1960 that the communist threat in Southeast Asia required priority, especiallyLaos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

. However Kennedy put more emphasis on South Vietnam, which he had visited as a reporter in 1951. In May, he dispatched Lyndon Johnson to tell Diem that Washington would help him build a fighting force that could resist the communists. Before that army could fight American combat troops would have to do the fighting.

As the Viet Cong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

became active Kennedy increased the number of military advisers and special forces

Special forces and special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

from under 1000 1960 to 16,000 by late 1963. They trained and advised the South Vietnamese forces but did not fight the enemy. In March 1965, President Lyndon Johnson, committed the first combat troops to Vietnam and greatly escalated U.S. involvement. US forces reaching 184,000 in 1965 and peaked at 536,000 in 1968, not counting The US Air Force which was based outside Vietnam.

The British had suggestions based on their success in defeating the Communist insurrection in Malaya. The result was the Strategic Hamlet Program

The Strategic Hamlet Program (SHP; vi, Ấp Chiến lược, link=no ) was a plan by the government of South Vietnam in conjunction with the US government and ARPA during the Vietnam War to combat the communist insurgency by pacifying the count ...

starting in 1962. It involved some forced relocation, village internment, and segregation of rural South Vietnamese into new communities where the peasantry would be isolated from Communist insurgents. It was hoped that these new communities would provide security for the peasants and strengthen the tie between them and the central government. The program ended in 1964.

In 1963 the U.S. became frustrated when Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

used the newly trained forces to crush Buddhist demonstrations. Kennedy sent Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and General Maxwell D. Taylor on the McNamara Taylor mission

Mac Conmara (anglicised as MacNamara or McNamara) is an Irish surname of a family of County Clare in Ireland. The McNamara family were an Irish clan claiming descent from the Dál gCais and, after the O'Briens, one of the most powerful famili ...

to figure out what was happening. Diem ignored the protests and was overthrown by the military. The U.S. did not order the coup but approved its actions after it happened, while regretting that Diem was killed in the process. The coup solved the Diem Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

would be badly hurt. At the same time, the administration downplayed the escalating War, diverting away the attention of the American people. As senior officials realized matters were getting worse and worse, public relations made it seem the United States was in full control of this not very important episode. There were no parades for returning veterans. Washington made no calls for victory. Johnson undermined the military by refusing to call up the Army Reserves or the state-based National Guard, because this would draw too much attention to the war. Instead he relied more and more heavily on the draft, which because of educational and occupational exemptions was reaching more and more to poor whites and blacks, who increasingly resented the war they had to fight. American people were indeed paying scant attention until the Viet Cong launched their massive Tet Offensive in early 1968. Militarily the Communists were badly defeated, but suddenly all Americans were shocked into aware that they were deeply engaged in a major war. The anti-war movement, up to the end of March no effort on college campuses suddenly took center stage, especially after protesting students were shot down on two college campuses. leading Democrats including Hubert Humphrey and Robert Kennedy protested the war and challenge Johnson for renomination in the 1968 election. Johnson's popularity was collapsing and he pulled out of the race.

Nixon, Ford and Vietnam

Nixon more than most presidents integrated his foreign policy and domestic policy with the goal of building of a majority voter coalition. At a time of deep angry divisions especially at the elite level over the war in Vietnam, as well as race relations and generational misunderstandings on sex and gender, his main goal in foreign policy was taking advantage of the profound split between Moscow and Beijing, forcing both sides to curry American favor. He needed both sides to abandon North Vietnam, which both of them did. This opened the way for Nixon's new strategy ofVietnamization

Vietnamization was a policy of the Richard Nixon administration to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War through a program to "expand, equip, and train South Vietnamese forces and assign to them an ever-increasing combat role, at the same ti ...

. The idea was to create and strengthen a South Vietnam army that could defend its own territory and bring peace with honor as American forces pulled out of Vietnam.

In 1968 Nixon carefully avoided entanglement in Vietnam (Humphrey ridiculed his silence by saying that Nixon was keeping "secret" his plans.) The US was in Vietnam because of its commitment to an obsolete policy of global containment of communism. Nixon's solution in Vietnam was "Vietnamization"—to turn the war over to Saigon, withdrawing all US ground forces by 1971. Ignoring critics who said he was prolonging the war, he set his timetable by the rate at which he could obtain tacit approval from Moscow, Beijing, and Saigon itself. Eventually his policy worked: Saigon did take over the war; there and elsewhere containment was replaced by the "Nixon Doctrine" that countries have to defend themselves. Meanwhile, the antiwar forces on the home front were self-destructing, spinning headlong into violence, drugs, and a radicalism (typified by the Weathermen) that provoked a strong backlash in Nixon's favor. When he saw Mao in Beijing in February 1972, the guerrilla war was virtually over, with the Viet Cong defeated. Hanoi, however, disregarded the advice of its allies and launched its conventional forces in the Easter, 1972, invasion of the South. Saigon fought back, and with strong American air support, routed the communists. Peace was at hand, as Kissinger said, but first Saigon had to be reassured of guaranteed future American support. This assurance came in the Operation Linebacker II

Operation Linebacker II was an aerial bombing campaign conducted by U.S. Seventh Air Force, Strategic Air Command and U.S. Navy Task Force 77 against targets in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam ( North Vietnam) during the final period of ...

air campaign in December 1972, when for the first time in the war Hanoi and its port were attacked. Reeling from the blows, Hanoi signed peace accords in Paris in January 1973, and released all American prisoners. Nixon, having achieved what he pronounced to be "peace with honor," immediately withdrew all US air and naval combat forces and ended the draft; he continued heavy shipments of modern new weapons into South Vietnam despite mounting demands from Congress that all aid be stopped.

Both Moscow and Beijing reduced sharply their military, economic and diplomatic support for North Vietnam. Hanoi, rapidly losing its outside support, and facing increase American bombing campaigns, finally came to terms. Nixon could announce he had achieved peace. China had suffered for years from Mao's erratic foreign policy which left it without strong supporters. Now it was eager to come to a deal with Nixon. Using Pakistan as an intermediary Henry Kissinger secretly flew to China to negotiate terms. In one of the most dramatic diplomatic episodes in the twentieth century Nixon himself flew to China to seal the deal with Mao Zedong. Moscow as astonished as everyone else by the turnaround, agreed to Nixon's terms regarding extensive previous reducing the risk of nuclear warfare.

As a result of the elaborate maneuvering by Nixon and his top advisor Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, the situation in Vietnam in 1973 saw the withdrawal of all American forces, the buildup of the South Vietnamese Army, and the weakening of the North Vietnamese by the loss of their two critical backers China and the Soviet Union. Nixon promised Saigon heavy support in terms of money and munitions. However Nixon's prestige at home collapsed during the Watergate scandal of 1974, and Congress cut off support to South Vietnam. Republican Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, the appointed vice president, replaced Nixon in August 1974, but he was in very weak position in foreign policy terms, has the Republican conservative opposition led by California's Ronald Reagan denounced the next Nixonian policy of détente with Beijing and Moscow. Saigon felt abandoned and lost self-confidence. In 1976 it was quickly overrun by an invasion from North Vietnam in the spring of 1975. Vietnam, victorious, turned against China. They fought a punishing short war in 1975.

Cambodia: Khmer Republic (1970–1975) and Khmer Rouge (1975–1978)

As part of the Vietnamization strategy the United States the sister that could a tie in Cambodia in 1970 that brought a friendly government. It tried to cut the secrets apply lines he's by the Communists in North Vietnam to supply the South, and as a result North Vietnam invaded the border provinces of Cambodia. United States Army enter the conflict to drive out the North Vietnamese, and the US Air Force open to massive bombing campaign against the communist supply lines. When United States withdrew from South Vietnam and also withdrew from Cambodia, allowing the North Vietnamese to take over that country in 1975, just days after it took control of South Vietnam. In 1975 Cambodia was taken over by an extreme communist faction, the Khmer Rouge. About two million civilians were killed, or a quarter of the population. In November 1975 Vietnam, with support from the USSR, Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge had material support from Communist China. It collapsed by 1979 leaving Vietnam in full control.Malaya

Malayan Emergency (1948–1960)

The ''Malayan Emergency'' (19481960) was a guerrilla war fought in theFederation of Malaya

The Federation of Malaya ( ms, Persekutuan Tanah Melayu; Jawi script, Jawi: ) was a federation of what previously had been British Malaya comprising eleven states (nine Malay states and two of the British Empire, British Straits Settlements, P ...

(now Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

) between Communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the Malayan Communist Party's (MCP) armed wing, against the armed forces of Great Britain and the British Commonwealth. The largely Chinese communist sought independence and a socialist economy. The British fought to defeat the expansion of communism and protect British economic and geopolitical interests. The fighting spanned both the colonial period and the creation of an independent Malaya in 1957. According to Michael Sullivan, The British commander General Gerald Templer

Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer, (11 September 1898 – 25 October 1979) was a senior British Army officer. He fought in both the world wars and took part in the crushing of the Arab Revolt in Palestine. As Chief of the Imperia ...

(1898–1979) argued that traditional combat would not win. He redirected the British effort from winning battles to winning popular support by providing relief, social change, and economic stability. Militarily he concentrated on small-unit anti-guerrilla operations. The British finally won by cutting off supply and retreat avenues for the guerrillas.

Communist insurgency (1968–1989)

The Communist insurgency was a guerrilla war waged between theMalayan Communist Party

The Malayan Communist Party (MCP), officially the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), was a Marxist–Leninist and anti-imperialist communist party which was active in British Malaya and later, the modern states of Malaysia and Singapore from ...

(MCP) and Malaysian federal security forces.

Following the end of the Malayan Emergency in 1960, the predominantly ethnic Chinese

The Chinese people or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by speakers of s ...

Malayan National Liberation Army

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army, was a communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the British Empire during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) and l ...

, armed wing of the MCP, had retreated to the Malaysian-Thailand border where it had regrouped and retrained for future offensives against the Malaysian government. Major fighting broke out in June 1968. The conflict also coincided with renewed domestic tensions between ethnic Malays and Chinese in Peninsular Malaysia and regional military tensions due to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

While the Malayan Communist Party received some limited support from China, this support ended when the two governments established diplomatic relations in June 1974. In 1970, the MCP experienced a schism which led to the emergence of two breakaway factions: the Communist Party of Malaya– Marxist-Leninist (CPM–ML) and the Revolutionary Faction (CPM–RF). Despite efforts by the MCP to appeal to much larger population of ethnic Malays, the organisation was dominated by Chinese Malaysians throughout the war.

The insurgency came to an end on 2 December 1989 when the MCP signed a peace accord

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a ...

with the government. This coincided with the Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Natio ...

and the collapse of several prominent communist regimes worldwide. Besides the fighting on the Malay Peninsula, another long-running communist insurgency was suppressed in the Malaysian state of Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the M ...

in the island of Borneo.

Indonesia

Mao forged an alliance withSukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

's dictatorship in Indonesia in the early 1960s. His strategy was to win over Third World countries in the face of competition with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. In Southeast Asia, Mao had the advantage of strong ethnic ties to the 2-million-member Chinese element in Java. He was driven by an ideological commitment to the Maoist version grass roots efforts to further the communist movement. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union kept up with its Chinese rival by provided large supplies of warplanes, small warships, and advanced military hardware.

Sukarno was enabled to threaten the emerging state of Malaysia in what is known as the He swore to destroy Malaysia because it included territory that Indonesia also claimed. He launched multiple small scale operations such as stopping trade with Singapore, sending guerrillas into Malaysian territory in Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak), and sending in light commando raids across the Malacca Straits. In the 1957 Anglo-Malayan Defence Agreement, Great Britain had guaranteed the security of Malaya against. In response to Sukarno. Britain, along with Australia and New Zealand, sent in naval and air forces as well as infantry.

Under the leadership of D. N. Aidit

Dipa Nusantara Aidit (born Ahmad Aidit; 30 July 1923 – 22 November 1965) was an Indonesian communist politician, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) from 1951 until his summary execution during the Indones ...

the Communist Party of Indonesia

The Communist Party of Indonesia (Indonesian: ''Partai Komunis Indonesia'', PKI) was a communist party in Indonesia during the mid-20th century. It was the largest non-ruling communist party in the world before its violent disbandment in 1965. ...

(the PKI) became the third largest in the world after those in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and the Soviet Union. It was the largest party in Indonesia and pushed Sukarno further and further to the left, despite growing opposition from Muslim conservatives and the army. On September 30. 1965, a military coup attempt killed six senior anti-communist generals. However, in a quick response General Suharto led a major anti-communist coup that overthrew Sukarno and massacred hundreds of thousands of PKI supporters, including Aidit and the top leadership, while another 200,000 Chinese fled Indonesia. Washington did not directly participate.

The new Indonesian government made peace with Malaysia, although it continued anti-imperialistic rhetoric against the British. Despite its military successes, Britain found itself overextended; furthermore by committing itself to defending Malaysia instead of South Vietnam it alienated Washington.

Thailand

In 1954 Thailand joined theSoutheast Asia Treaty Organization

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

(SEATO) to become an active ally of the United States in the Cold War. In 1962 came the Rusk-Thanat Agreement in which the U.S. promised to defend Thailand and fund its military. Thailand became the main launching point for 80 percent of American bombing campaigns during the Vietnam War. In 1966–1968 the 25,000 Americans stationed in Thailand launched an average of 1500 sorties a week. In addition, 11,000 Thai soldiers served in South Vietnam, and 22,000 fought in Laos.

South Asia

India

Until the early 1970s India was neutral in the Cold War, and was a key leader in the worldwideNon-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

. However, in 1971, it began a loose alliance with the Soviet Union, as Pakistan was allied to the United States and China. India became a nuclear-weapon state, with its first nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

in 1974. India had territorial disputes with China which in 1962 escalated into the Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tib ...

. It had major disputes and with Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

which resulted in wars in 1947

It was the first year of the Cold War, which would last until 1991, ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Events

January

* January–February – Winter of 1946–47 in the United Kingdom: The worst snowfall in the country in ...

, 1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is Second inauguration of Lyndo ...

, 1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses ( February 25, July 22 and August 20) and two total lunar eclipses (February 10, and August 6).

The world population increased by 2.1% this year, the highest increase in history.

Events

Ja ...

and 1999.

From the late 1920s on, Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, who had a long-standing interest in world affairs among independence leaders, formulated the Congress Party stance on international issues. As Prime Minister and Minister of External Affairs 1947–1964, Nehru controlled India's approach to the world. India's international influence varied over the years. It gained prestige and moral authority in the 1950s because of its moralistic leadership of the nonaligned movement. However Cold War politics became intertwined with interstate relations. It was too close to Moscow to be nonaligned.

Seizure of Portuguese colony of Goa

For years India demanded that Portugal turn over its old colony ofGoa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

on the west coast. Portugal tried and failed to get serious diplomatic support from NATO and the U.S. To protect his pacifistic reputation Nehru attacked Portugal's poor record of colonial mismanagement and its status as the last imperial power. Therefore, he rallied the nonaligned nations at Bandung in 1955 to denounce colonialism.

Finally in December 1961, Nehru sent in 45,000 troops against 3500 defenders and annexed Goa with few casualties. After the event the UN debated the issue in early 1962. The US delegate, Adlai Stevenson, strongly criticised India's use of force, stressing that such resort to violent means was against the charter of the UN. He stated that condoning such acts of armed forces would encourage other nations to resort to similar solutions to their own disputes, and would lead to the death of the United Nations. In response, the Soviet delegate, Valerian Zorin

Valerian Aleksandrovich Zorin (russian: Валериан Александрович Зорин; 14 January 1902 – 14 January 1986) was a Soviet diplomat best remembered for his famous confrontation with Adlai Stevenson on 25 October 1962, duri ...

, argued that the Goan question was wholly within India's domestic jurisdiction and could not be considered by the Security Council. He also drew attention to Portugal's disregard for UN resolutions calling for the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples. In the end the Soviet veto prevented any UN action, but only a few countries besides the Soviet bloc and the Arab states supported India.

India and USSR

Stalin wanted the Indian independence movement to emphasize on class conflict, but instead it stressed on bourgeois nationalism along with British-style socialism. After the death of Stalin in 1953, the new leaders in Moscow decided to work with bourgeoisie nationalists like Nehru in order to minimize American influence. India and the Soviet Union (USSR) built a strong strategic, military, economic and diplomatic relationship. After 1960 both were hostile to China and its ally Pakistan. It was the most successful of the Soviet attempts to foster closer relations with Third World countries. Nehru had complete control of foreign policy; he went the Soviet Union in June 1955, and Soviet leaderNikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

made a return visit in the fall of 1955. Khrushchev announced that the Soviet Union supported Indian sovereignty over Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

against Pakistan's claims, and also over Portuguese claims to Goa.

Khrushchev's closeness with India was one more ingredient in Beijing's complaints about Moscow. The Soviet Union declared its neutrality during the 1959 border dispute and the Sino-Indian war

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tib ...

of October 1962. By 1960 India had received more Soviet military assistance than China had, to Mao's anger. In 1962 Moscow agreed to transfer technology to co-produce the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 (russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-21; NATO reporting name: Fishbed) is a supersonic jet aircraft, jet fighter aircraft, fighter and interceptor aircraft, designed by the Mikoyan, Mikoyan-Gurevich OKB, De ...

jet fighter in India, which had earlier been denied to China.

In 1965-66 Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

served successfully as peace broker between India and Pakistan to end the Indian-Pakistani border war of 1965.

In 1971, East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

- supported by India - rebelled

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against West Pakistan

West Pakistan ( ur, , translit=Mag̱ẖribī Pākistān, ; bn, পশ্চিম পাকিস্তান, translit=Pôścim Pakistan) was one of the two Provincial exclaves created during the One Unit Scheme in 1955 in Pakistan. It was d ...

. India secured the support of the Soviet Union, including protection against Chinese intervention, in August 1971 with the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation

The Indo–Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation was a treaty signed between India and the Soviet Union in August 1971 that specified mutual strategic cooperation. This was a significant deviation from India's previous position of ...

before openly entering the conflict in December 1971. In the ensuing Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military confrontation between India and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 until the

Pakistani capitulation in Dhaka on 16 Decem ...

, India defeated Pakistan and East Pakistan became independent as Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

.

Relations between the Soviet Union and India did not suffer much during the right-wing Janata Party

The Janata Party ( JP, lit. ''People's Party'') was a political party that was founded as an amalgam of Indian political parties opposed to the Emergency that was imposed between 1975 and 1977 by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of the Indian Nati ...

's coalition government in 1977–1979, although India did move to establish better economic and military relations with Western countries. To counter these efforts by India to diversify its relations, the Soviet Union proffered additional weaponry and economic assistance. Mrs Gandhi returned to power in early 1980 and resumed close relations. She was conspicuous in the Third World for not criticizing the Soviet invasion underway in Afghanistan.

When Indira Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, her son Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

replaced her and continued the close relationship with Moscow. Indicating the high priority of relations with the Soviet Union in Indian foreign policy, the new Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

, visited the Soviet Union on his first state visit abroad in May 1985 and signed two long-term economic agreements with the Soviet Union. He avoided public criticism of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. When Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

became the leader in Moscow his first visit to a Third World state was to New Delhi in late 1986. Gorbachev unsuccessfully urged Rajiv Gandhi to help the Soviet Union set up an Asian collective security system. Gorbachev's advocacy of this proposal, which had also been made by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet Union, Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Gener ...

, was an indication of continuing Soviet interest in using close relations with India as a means of containing China. With the improvement of Sino-Soviet relations in the late 1980s, containing China had less of a priority, but close relations with India remained important as an example of Gorbachev's new Third World policy.

Burma/Myanmar

Burma gained independence from Britain in tense fashion in 1948. It avoided any commitment in the Cold War, and was active in the nonaligned movement. There were numerous failed Communist uprisings. The army took control in 1962. The Soviet Union never played a prominent role, and Burma kept its distance from Britain and the United States. China shares a long controversial border, and relations were usually poor until the late 1980s. In the 1950s Burma lobbied for China's entry as a permanent member into the UN Security Council, but denounced the China's invasion of Tibet in 1950. The last border dispute came in 1956, when the Chinese invaded parts of northern Burma, but were repulsed. In the 1960s students and other elements of Burma's large Chinese community expressed support for Maoism; anti-Chinese riots resulted. Close relations began in the late 1980s as China began supplying the military junta with the majority of its arms in exchange for increased access to Burmese markets and intelligence opportunities. China refused to join other nations that condemned Myanmar's policy toward minorities, especially the attacks on the Rohingya Muslims that began in the 1970s.Pakistan

Since its independence in 1947, Pakistan's foreign policy has encompassed difficult relations with the neighbouringSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

(USSR) who maintained a close military and ideological interaction with the neighbouring countries such as Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and India. During most of 1947–1991, the USSR support was given to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, over which it has fought three wars on Kashmir conflict

The Kashmir conflict is a territorial conflict over the Kashmir region, primarily between India and Pakistan, with China playing a third-party role. The conflict started after the partition of India in 1947 as both India and Pakistan claim ...

.

Pakistan first aligned itself with the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

during the 1950s a few years after gaining independence in 1947. Pakistan took part in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

and Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

on the side of the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

. Pakistan joined SEATO

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

and CENTO

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Tur ...

in 1954 and 1955 respectively. During the 1960s Pakistan was closely aligned to the United States; receiving economic and military assistance. Pakistan was important for the US because of its strategic location close to the Soviet Union and bordering China.

In the early 1970s, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

was engaged in a war with India during which the Soviets supported the latter. With limited and less assistance and military and diplomatic aid during the war Pakistan's relation with the US was hindered for the next decade. The ongoing war with India resulted in the succession of East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

lost the privilege of being a member of SEATO

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

. With the growing Soviet influence in the region, Pakistan cemented close security relations with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

during most of the Cold War. While Pakistan had "on-off relations" with the United States, Pakistan assisted President Nixon's famous 1972 visit to China .

Relations with the United States cycled through varying levels of friendliness, but Pakistan consistently found themselves on the United States side of issues faced during the Cold War. Pakistan served as a geostrategic position for United States military bases during the Cold War since it bordered the Soviet Union and China. These positive relations would fall apart following successful cooperation in fighting the Soviet Union's influence in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

and the subsequent fall of the Soviet Union.

Sri Lanka

Ceylon at first was closely tied to Great Britain, which awarded independence in 1947 in a friendly manner. The Royal Navy maintained a major naval base; trade with Britain dominated the economy. Under Prime MinisterS. W. R. D. Bandaranaike

Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike ( si, සොලොමන් වෙස්ට් රිජ්වේ ඩයස් බණ්ඩාරනායක; ta, சாலமன் வெஸ்ட் ரிட்ஜ்வே டயஸ் ப� ...

(1956–1959) Ceylon moved away from the West and closed the British base. It became prominent in the non-aligned movement under prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike

Sirima Ratwatte Dias Bandaranaike ( si, සිරිමා රත්වත්තේ ඩයස් බණ්ඩාරනායක; ta, சிறிமா ரத்வத்தே டயஸ் பண்டாரநாயக்கே; 17 April 191 ...

. (1960–1965). The rise of Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism

Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism is a Sri Lankan political ideology which combines a focus upon Sinhalese culture and ethnicity (nationalism) with an emphasis upon Theravada Buddhism, which is the majority belief system of most of the Sinhalese in ...

led to a name change to Sri Lanka, a loss of influence by the British oriented elite, and repression the Tamil minority. Civil war erupted, lasting to 2009. India offered to mediate and sent 45,000 troops to neutralize the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE; ta, தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகள், translit=Tamiḻīḻa viṭutalaip pulikaḷ, si, දෙමළ ඊළාම් විමුක්ති කොටි, t ...

(LTTE), the Tamil army. After 1970 China provided economic and military aid, and purchased rubber. China's goal was to limit the growth of Indian and Soviet power in South Asia.

Middle East

Lawrence Freedman

Sir Lawrence David Freedman, (born 7 December 1948) is a British academic, historian and author with specialising in foreign policy, international relations and strategy. He has been described as the "dean of British strategic studies" and wa ...

, ''A choice of enemies: America confronts the Middle East'' (Hachette, 2010) provides detailed coverage of Washington's complex relations with the critical region of Jews and Arabs, Sunnis and Shias, and massive oil supplies.

Afghanistan

USSR

The Afghanistan War (1978–92) was a civil war inAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

that pitted the Soviet Union and its Afghan allies against a coalition of anti-Communist groups called the mujahideen

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' ( ar, مُجَاهِدِين, mujāhidīn), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' ( ar, مجاهد, mujāhid, strugglers or strivers or justice, right conduct, Godly rule, etc. doers of jihād), an Arabic term th ...

, supported from the outside by the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. The war ended the détente period of the Cold War. It climaxed in a humiliating defeat for the Soviets, who pulled out in 1989, and for their clients who were overthrown in 1992.

The world was stunned in 1979 when the Soviets sent their army into Afghanistan, which had always been neutral and uninvolved. The UN General Assembly voted by 104 to 18 with 18 abstentions to "strongly deplore" the "recent armed intervention" and demanded the "total withdrawal of foreign troops.". The old regime

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

was replaced by the Marxist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The Afghanistan crisis began in April 1978 with a coup d'état by Afghan Communists called the Saur Revolution. They tried to impose scientific socialism on a country that did not want to be modernized—indeed, which was heading in the opposite direction under the lure of Muslim fundamentalism of the sort that had topped the Shah in next-door Iran. Disobeying orders from Moscow, the coup leaders systematically executed the leadership of the large Parcham clan, thus guaranteeing a civil war among the country's many feuding ethnic groups, especially the rival . In addition the Communists in Afghanistan were themselves bitterly divided between the Khalq

Khalq ( ps, خلق, ) was a faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Its historical ''de facto'' leaders were Nur Muhammad Taraki (1967–1979), Hafizullah Amin (1979) and Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy (1979–1990). It was also ...

and Parcham

Parcham (Pashto and prs, پرچم, ) was the name of one of the factions of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, formed in 1967 following its split and led for most of its history by Babrak Karmal and Mohammed Najibullah. The basic id ...

factions. Moscow confronted a quandary. Afghanistan had been neutralized for sixty years, and had never been part of the Cold War system. Now it appeared that radical fundamentalist Muslims, supported by Pakistan and Iran, and probably by China and the United States, were about to seize power. The Communist regime in Kabul had no popular support; its 100,000-man army had fallen apart and was worthless. Only the Soviet army could possibly quell the growing rebellion by Parcham, the fundamentalist "mujahideen", and allied tribes who opposed the anti-religious, feminist modernizersOdd Arne Westad, "Afghanistan: Perspectives on the Soviet War." ''Bulletin of Peace Proposals'' 20#3 (1989): 281-9online

/ref> The Kremlin never realized the dangers involved and did not have even a basic understanding of the forces they confronted. According to Leninist principles, Afghanistan was not ready for revolution in the first place. Furthermore, intervention would destroy détente with the United States and Western Europe. Factions within the Afghan People's Democratic Party (Communist) government that were hostile to Soviet interests gained ascendancy and raised the specter of an independently minded Communist state located on the southern border that might cause future trouble inside the Muslim parts of the USSR. At this point Moscow decided not to send troops but instead stepped up shipments of military equipment such as artillery, armored personnel carriers and 48,000 machine guns; they also sent 100,000 tons of wheat. Moscow's first man in Kabul was prime minister

Nur Muhammad Taraki

Nur Muhammad Taraki (; 14 July 1917 – 9 October 1979) was an Afghan revolutionary communist politician, journalist and writer. He was a founding member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) who served as its General Secret ...

(1913–1979), who was murdered and replaced by his deputy Hafizullah Amin

Hafizullah Amin (Pashto/ prs, حفيظ الله امين; 1 August 192927 December 1979) was an Afghan communist revolutionary, politician and teacher. He organized the Saur Revolution of 1978 and co-founded the Democratic Republic of Afghan ...

(1929–1979) of the Khalq faction in September 1979. Although Amin called himself a loyal Communist, and begged for more Soviet military intervention, Moscow thought Amin was planning to double-cross them and switch over to China and the US. They therefore double crossed him first. Moscow had Amin officially invite the Soviet Army to enter Afghanistan; it did so in December 1979, and it immediately executed Amin and installed a Soviet puppet Babrak Karmal

Babrak Karmal (Farsi/Pashto: , born Sultan Hussein; 6 January 1929 – 1 or 3 December 1996) was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Part ...

(1929–1996), the leader of the more moderate Parcham faction of the PDPA. Pressure for intervention seems to have come primarily from the KGB (secret police), whose efforts to assassinate Amin had failed, and from the Red Army, which perhaps was worried about the danger of a mutiny on the part of its many Muslim soldiers.

World reaction

In July, 1979, before the Soviet invasion, President Jimmy Carter for the first time authorized the CIA to start assisting the Mujahideen rebels with money and non-military supplies sent via Pakistan. As soon as the Soviets invaded in December, 1979, Carter, disgusted at the collapse of détente and alarmed at the rapid Soviet gains, terminated progress on arms limitations, slapped a grain embargo on Russia, withdrew from the 1980 Moscow Olympics, and (with near-unanimous support in Congress) sent the CIA in to arm, train and finance the Mujahideen rebels. The US had strong support from Britain, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, all of whom feared the Soviet invasion was the first step in a grand move south toward the oil-rich Persian Gulf. Carter enlarged his position into the "Carter Doctrine," by which the US announced its intention to defend the Gulf. Historians now believe that analysis was faulty and that the Soviets were not planning a grand move, but were concerned with loss of prestige and the possibility of a hostile Muslim regime that might destabilize its largely Muslim southern republics.Richard Ned Lebow, and Janice Gross Stein, "Afghanistan, Carter, and foreign policy change: The limits of cognitive models." in ''Diplomacy, Force, and Leadership'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 95-127. The boycott of the Olympics humiliated the Soviets, who had hoped the games would validate their claim to moral equality in the world of nations; instead they were pariahs again.=American pressure