Clermont Ferrand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Clermont-Ferrand (, ; ; oc, label=

INSEE It is the prefecture (capital) of the

Auvergnat

or (endonym: ) is a northern dialect of Occitan spoken in central and southern France, in particular in the former administrative region of Auvergne.

Currently, research shows that there is not really a true Auvergnat dialect but rather a va ...

, Clarmont-Ferrand or Clharmou ; la, Augustonemetum) is a city and commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics ( physical geography), human impact characteristics ( human geography), and the interaction of humanity an ...

, with a population of 146,734 (2018). Its metropolitan area (''aire d'attraction'') had 504,157 inhabitants at the 2018 census.Comparateur de territoire: Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Clermont-Ferrand (022), Unité urbaine 2020 de Clermont-Ferrand (63701), Commune de Clermont-Ferrand (63113)INSEE It is the prefecture (capital) of the

Puy-de-Dôme

Puy-de-Dôme (; oc, label=Auvergnat, lo Puèi de Doma or ''lo Puèi Domat'') is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in the centre of France. In 2019, it had a population of 662,152.department.

Clermont ranks among the oldest cities of France. The first known mention was by the Greek geographer Strabo, who called it the "metropolis of the Arverni" (meaning their ''

Clermont ranks among the oldest cities of France. The first known mention was by the Greek geographer Strabo, who called it the "metropolis of the Arverni" (meaning their ''

Clermont was the starting point of the

Clermont was the starting point of the

Clermont-Ferrand has two famous churches. One is Notre-Dame du Port, a Romanesque church which was built during the 11th and 12th centuries (the bell tower and was rebuilt during the 19th century). It was nominated as a

Clermont-Ferrand has two famous churches. One is Notre-Dame du Port, a Romanesque church which was built during the 11th and 12th centuries (the bell tower and was rebuilt during the 19th century). It was nominated as a

* Jardin Lecoq

* Parc de Montjuzet

*

* Jardin Lecoq

* Parc de Montjuzet

*

The

The

Clermont-Ferrand was the home of mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal who tested

Clermont-Ferrand was the home of mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal who tested

Olivier Bianchi

Olivier Bianchi (born June 10, 1970, in Paris) is a French politician. A member of the Socialist Party (France), Socialist Party, he has been mayor of Clermont-Ferrand since April 4, 2014 and president of Clermont Auvergne Métropole since April 2 ...

is its current mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

.

Clermont-Ferrand sits on the plain of Limagne

The Limagne () is large plain in the Auvergne region of France in the valley of the Allier river, on the edge of the Massif Central. It lies entirely within the ''département'' of Puy-de-Dôme. The term is sometimes used to include this, and t ...

in the Massif Central

The (; oc, Massís Central, ; literally ''"Central Massif"'') is a highland region in south-central France, consisting of mountains and plateaus. It covers about 15% of mainland France.

Subject to volcanism that has subsided in the last 10,0 ...

and is surrounded by a major industrial area. The city is known for the chain of volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the Crust (geology), crust of a Planet#Planetary-mass objects, planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and volcanic gas, gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Ear ...

es, the Chaîne des Puys

The Chaîne des Puys () is a north-south oriented chain of cinder cones, lava domes, and maars in the Massif Central of France. The chain is about 40 km (25 mi) long, and the identified volcanic features, which constitute a volcanic ...

, which surround it. This includes the dormant volcano Puy de Dôme

Puy de Dôme (, ; oc, label=Auvergnat, Puèi Domat or ) is a lava dome and one of the youngest volcanoes in the region of Massif Central in central France. This chain of volcanoes including numerous cinder cones, lava domes and maars is ...

(), one of the highest in the surrounding area, which is topped by communications towers and visible from the city. Clermont-Ferrand has been listed as a "tectonic hotspot" since July 2018 on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

One of the oldest French cities, it has been known by Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

as the capital of the Arvernie Tribe before developing under the Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

era under the name of Augustonemetum in the 1st century BC. The forum of the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

city was located on the top of the Clermont mound, on the site of the present cathedral. During the decline of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

it was subjected to repeated looting by the peoples who invaded Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, including Vandals, Alans, Visigoths and Franks. It was later raided by Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

during the weakening of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

. Growing in importance under the Capetian dynasty, in 1095 it hosted the Council of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

Pope Urban's speech ...

, where Pope Urban II called the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic r ...

. In 1551, Clermont became a royal town, and further made in 1610, inseparable property of the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

.

Today Clermont-Ferrand hosts the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival

The Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival (French: ''Festival international du court métrage de Clermont-Ferrand'') is an international film festival dedicated to short films held annually in Clermont-Ferrand, France.

History

In ...

(''Festival du Court-Métrage de Clermont-Ferrand''), one of the world's leading international festivals for short films. It is also home to the corporate headquarters of Michelin, the global tyre company founded there more than 100 years ago. With a quarter of the municipal population being students, and 6,000 researchers, Clermont-Ferrand is the first city in France to join the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

Learning City Network.

Along with its highly distinctive black lava stone Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

Cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominatio ...

, Clermont-Ferrand's most famous site includes the public square

A town square (or square, plaza, public square, city square, urban square, or ''piazza'') is an open public space, commonly found in the heart of a traditional town but not necessarily a true geometric square, used for community gatherings. ...

Place de Jaude, on which stands a grand statue of Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix (; Greek: Οὐερκιγγετόριξ; – 46 BC) was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. Despite ha ...

astride a warhorse and brandishing a sword. The inscription reads: ''J'ai pris les armes pour la liberté de tous'' (''I took up arms for the liberty of all''). This statue was sculpted by Frédéric Bartholdi

Frédéric and Frédérick are the French versions of the common male given name Frederick. They may refer to:

In artistry:

* Frédéric Back, Canadian award-winning animator

* Frédéric Bartholdi, French sculptor

* Frédéric Bazille, Impres ...

, who also created the Statue of Liberty.

History

Name

Clermont-Ferrand's first name was Augustonemetum. It was born on the central knoll where the cathedral is situated today. It overlooked the capital of Gaulish Avernie. The fortified castle of Clarus Mons gave its name to the whole town in 848, to which the small episcopal town of Montferrand was attached in 1731, together taking the name of Clermont-Ferrand. The old part of Clermont is delimited by the route of the ramparts, as they existed at the end of the Middle Ages. The town of Clermont-Ferrand came about with the joining together of two separate towns, Clermont and Montferrand, which was decreed byLouis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

and confirmed by Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

.

Prehistoric and Roman

oppidum

An ''oppidum'' (plural ''oppida'') is a large fortified Iron Age settlement or town. ''Oppida'' are primarily associated with the Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread across Europe, stretchi ...

civitas'' or tribal capital). The city was at that time called ''Nemessos'' – a Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

word for a sacred forest, and was situated on the mound where the cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand stands today. Somewhere in the area around Nemossos the Arverni chieftain Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix (; Greek: Οὐερκιγγετόριξ; – 46 BC) was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. Despite ha ...

(later to head a unified Gallic resistance to the Roman invasion

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stane ...

led by Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

) was born around 72 BC. Also, Nemossos was situated not far from the plateau of Gergovia, where Vercingetorix repulsed the Roman assault at the Battle of Gergovia

The Battle of Gergovia took place in 52 BC in Gaul at Gergovia, the chief oppidum (fortified town) of the Arverni. The battle was fought between a Roman Republican army, led by proconsul Julius Caesar, and Gallic forces led by Vercingetorix, wh ...

in 52 BC. After the Roman conquest, the city became known as ''Augustonemetum'' sometime in the 1st century, a name which combined its original Gallic name with that of the Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

. Its population was estimated at 15,000–30,000 in the 2nd century, making it one of the largest cities of Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacient parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century ...

. It then became ''Arvernis'' in the 3rd century, taking its name, like other Gallic cities in this era, from the people who lived within its walls.

Early Middle Ages

The city became the seat of a bishop in the 5th century, at the time of the bishopNamatius

Saint Namatius ( French: ''Namace'') is a saint in the Roman Catholic church. He was the eighth or ninth bishop of Clermont (then called ''Arvernis'') from 446 to 462, and founded Clermont's first cathedral, bringing the relics of Saints Vital ...

or Saint Namace, who built a cathedral here described by Gregory of Tours. Clermont went through a dark period after the disappearance of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

and during the whole High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

, marked by pillaging by the peoples who invaded Gaul. Between 471 and 475, Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; oc, label= Occitan, Auvèrnhe or ) is a former administrative region in central France, comprising the four departments of Allier, Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal and Haute-Loire. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region Au ...

was often the target of Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

expansion, and the city was frequently besieged, including once by Euric

Euric (Gothic: ''* Aiwareiks'', see '' Eric''), also known as Evaric, or Eurico in Spanish and Portuguese (c. 420 – 28 December 484), son of Theodoric I, ruled as king (''rex'') of the Visigoths, after murdering his brother, Theodoric II, ...

. Although defended by Sidonius Apollinaris

Gaius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius, better known as Sidonius Apollinaris (5 November of an unknown year, 430 – 481/490 AD), was a poet, diplomat, and bishop. Sidonius is "the single most important surviving author from 5th-century Gaul ...

, at the head of the diocese from 468 to 486, and the patrician

Patrician may refer to:

* Patrician (ancient Rome), the original aristocratic families of ancient Rome, and a synonym for "aristocratic" in modern English usage

* Patrician (post-Roman Europe), the governing elites of cities in parts of medieval ...

Ecdicius Ecdicius Avitus (c. 420 – after 475) was an Arverni aristocrat, senator, and ''magister militum praesentalis'' from 474 until 475.

As a son of the Emperor Avitus, Ecdicius was educated at ''Arvernis'' (modern Clermont-Ferrand), where he lived an ...

, the city was ceded to the Visigoths by emperor Julius Nepos

Julius Nepos (died 9 May 480), or simply Nepos, ruled as Roman emperor of the West from 24 June 474 to 28 August 475. After losing power in Italy, Nepos retreated to his home province of Dalmatia, from which he continued to claim the western im ...

in 475 and became part of the Visigothic kingdom until 507. A generation later, it became part of the Kingdom of the Franks

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks duri ...

. On 8 November 535 the first Council of Clermont opened at Arvernis (Clermont), with fifteen bishops participating, including Caesarius of Arles

Caesarius of Arles ( la, Caesarius Arelatensis; 468/470 27 August 542 AD), sometimes called "of Chalon" (''Cabillonensis'' or ''Cabellinensis'') from his birthplace Chalon-sur-Saône, was the foremost ecclesiastic of his generation in Merovingia ...

, Nizier of Lyons, Bishop of Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

, and Saint Hilarius

Pope Hilarius (or Hilary) was the bishop of Rome from 19 November 461 to his death on 29 February 468.

In 449, Hilarius served as a legate for Pope Leo I at the Second Council of Ephesus. His opposition to the condemnation of Flavian of Constanti ...

, Bishop of Mende. The Council issued 16 decrees. The second canon reiterated the principle that the granting of episcopal dignity must be according to merit and not as a result of intrigues.

In 570, Bishop Avitus ordered the Jews of the city, who numbered over 500, to accept Christian baptism or be expelled.

In 848, the city was renamed ''Clairmont'', after the castle Clarus Mons. During this era, it was an episcopal city ruled by its bishop. Clermont was not spared by the Vikings at the time of the weakening of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

: it was ravaged by the Normans under Hastein Hastein (Old Norse: ''Hásteinn'', also recorded as ''Hastingus'', ''Anstign'', ''Haesten'', ''Hæsten'', ''Hæstenn'' or ''Hæsting'' and alias ''Alsting''Jones, Aled (2003). ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: Sixth Series'' Cambridge ...

or Hastingen in 862 and 864 and, while its bishop Sigon carried out reconstruction work, again in 898 (or 910, according to some sources). Bishop Étienne II built a new Romanesque cathedral which was consecrated in 946. It was almost entirely replaced by the current Gothic cathedral, though the crypt survives and the towers were only replaced in the 19th century.

Middle Ages

Clermont was the starting point of the

Clermont was the starting point of the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic r ...

, in which Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

sought to free Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

from Muslim domination. Pope Urban II preached the crusade in 1095, at the Second Council of Clermont. In 1120, following repeated crises between the counts of Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; oc, label= Occitan, Auvèrnhe or ) is a former administrative region in central France, comprising the four departments of Allier, Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal and Haute-Loire. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region Au ...

and the bishops of Clermont and in order to counteract the clergy's power, the counts founded the rival city of Montferrand on a mound next to the fortifications of Clermont, on the model of the new cities of the Midi

MIDI (; Musical Instrument Digital Interface) is a technical standard that describes a communications protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, computers, and ...

that appeared in the 12th and 13th centuries. Until the early modern period, the two remained separate cities: Clermont, an episcopal city; Montferrand, a comital

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

one.

Early Modern and Modern eras

Clermont became a royal city in 1551, and in 1610, the inseparable property of the French Crown. On 15 April 1630 the Edict of Troyes (the First Edict of Union) joined the two cities of Clermont and Montferrand. This union was confirmed in 1731 byLouis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

with the Second Edict of Union. At this time, Montferrand was no more than a satellite city

Satellite cities or satellite towns are smaller municipalities that are adjacent to a principal city which is the core of a metropolitan area. They differ from mere suburbs, subdivisions and especially bedroom communities in that they have m ...

of Clermont, and it remained so until the beginning of the 20th century. Wishing to retain its independence, Montferrand made three demands for independence, in 1789, 1848, and 1863.

In the 20th century, construction of the Michelin factories and of city gardens, which shaped modern Clermont-Ferrand, united the two cities, although two distinct downtowns survive and Montferrand retains a strong identity.

Geography

Climate

Clermont-Ferrand has an oceanic climate ( Cfb). The city is in the rain shadow of the Chaîne des Puys, giving it one of the driest climates in metropolitan France, except for a few places around the Mediterranean Sea. The mountains also block most of the oceanic influence of the Atlantic, which creates a climate much more continental than nearby cities west or north of the mountains, like Limoges and Montluçon. Thus the city has comparatively cold winters and hot summers. From November to March, frost is very frequent, and the city, being at the bottom of a valley, is frequently subject totemperature inversion

In meteorology, an inversion is a deviation from the normal change of an atmospheric property with altitude. It almost always refers to an inversion of the air temperature lapse rate, in which case it is called a temperature inversion. Nor ...

, in which the mountains are sunny and warm, and the plain is freezing cold and cloudy. Snow is quite common, although usually short-lived and light. Summer temperatures often exceed , with sometimes violent thunderstorms. The highest temperature was reached in 2019 of 40.9 °C (105.6 °F) while the lowest was -29.0 °C (-20.2 °F).

Main sights

Religious architecture

Clermont-Ferrand has two famous churches. One is Notre-Dame du Port, a Romanesque church which was built during the 11th and 12th centuries (the bell tower and was rebuilt during the 19th century). It was nominated as a

Clermont-Ferrand has two famous churches. One is Notre-Dame du Port, a Romanesque church which was built during the 11th and 12th centuries (the bell tower and was rebuilt during the 19th century). It was nominated as a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

by UNESCO in 1998. The other is Clermont-Ferrand Cathedral

Clermont-Ferrand Cathedral, or the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption of Clermont-Ferrand (french: Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption de Clermont-Ferrand), is a Gothic cathedral and French national monument located in the town of Cl ...

(''Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption de Clermont-Ferrand''), built in Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

** Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken ...

between the 13th and the 19th centuries.

Parks and gardens

* Jardin Lecoq

* Parc de Montjuzet

*

* Jardin Lecoq

* Parc de Montjuzet

* Jardin botanique de la Charme

The Jardin botanique de la Charme (18,000 m²), formerly known as the Jardin botanique de la Ville de Clermont-Ferrand, is a municipal botanical garden located at 10, rue de la Charme, Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dôme, Auvergne, France. It is open ...

* Arboretum de Royat The Arboretum de Royat (41 hectares) is an arboretum located in the '' forêt domaniale'' southwest of Royat, Puy-de-Dôme, Auvergne, France.

Royat is a spa town at the foot of the '' Parc des Volcans d'Auvergne'' and the Puy-de-Dôme, developed ...

* Jardin botanique d'Auvergne The Jardin botanique d'Auvergne (9 hectares), also known as the Jardin botanique d'essais de Royat-Charade, is a botanical garden located in Charade, Royat, Puy-de-Dôme, Auvergne, France.

The garden was established in 2007 as a joint undertaking b ...

Economy and infrastructure

Food production

The food industry is a complex, global network of diverse businesses that supplies most of the food consumed by the world's population. The food industry today has become highly diversified, with manufacturing ranging from small, traditiona ...

and processing as well as engineering are major employers in the area, as are the many research facilities of major computer software and pharmaceutical

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field an ...

companies.

The city's industry was for a long time linked to the French tyre manufacturer Michelin, which created the radial tyre

A radial tire (more properly, a radial-ply tire) is a particular design of vehicular tire. In this design, the cord plies are arranged at 90 degrees to the direction of travel, or radially (from the center of the tire). Radial tire construction ...

and grew up from Clermont-Ferrand to become a worldwide leader in its industry. For most of the 20th century, it had extensive factories throughout the city, employing up to 30,000 workers. While the company has maintained its headquarters in the city, most of the manufacturing is now done in foreign countries. This downsizing took place gradually, allowing the city to court new investment in other industries, avoiding the fate of many post-industrial cities and keeping it a very wealthy and prosperous area home of many high-income executives.

Transport

The

The main railway station

Central stations or central railway stations emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century as railway stations that had initially been built on the edge of city centres were enveloped by urban expansion and became an integral part of the ...

has connections to Paris and several regional destinations: Lyon, Moulins via Vichy, Le Puy-en-Velay, Aurillac, Nîmes, Issoire, Montluçon and Thiers.

The motorway A71 connects Clermont-Ferrand with Orléans and Bourges, the A75 with Montpellier and the A89 with Bordeaux, Lyon and Saint-Étienne ( A72). The airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport. Airports usually consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surfa ...

offers flights within France. Recently, Clermont-Ferrand was France's first city to get a new Translohr transit system, the Clermont-Ferrand Tramway, thereby linking the city's north and south neighbourhoods.

The TGV will arrive in Auvergne after 2030. It will be one of the last regions to not have a TGV stop.

Population

Culture

Clermont-Ferrand was the home of mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal who tested

Clermont-Ferrand was the home of mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal who tested Evangelista Torricelli

Evangelista Torricelli ( , also , ; 15 October 160825 October 1647) was an Italian physicist and mathematician, and a student of Galileo. He is best known for his invention of the barometer, but is also known for his advances in optics and work ...

's hypothesis concerning the influence of gas pressure on liquid equilibrium. This is the experiment where a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

is created in a mercury tube: Pascal's experiment had his brother-in-law carry a barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

to the top of the Puy-de-Dôme

Puy-de-Dôme (; oc, label=Auvergnat, lo Puèi de Doma or ''lo Puèi Domat'') is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in the centre of France. In 2019, it had a population of 662,152.Université Blaise-Pascal (or Clermont-Ferrand II) was located primarily in the city and is named after him.

Clermont-Ferrand also hosts the

*

*

* Chakir Ansari (born 1991), Moroccan freestyle wrestler, competed at the 2016 Summer Olympics

*

* Chakir Ansari (born 1991), Moroccan freestyle wrestler, competed at the 2016 Summer Olympics

*

*

*

Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival

The Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival (French: ''Festival international du court métrage de Clermont-Ferrand'') is an international film festival dedicated to short films held annually in Clermont-Ferrand, France.

History

In ...

, the world's first international short film festival which originated in 1979. This festival, which brings thousands of people every year (137,000 in 2008) to the city, is the second French film

French cinema consists of the film industry and its film productions, whether made within the nation of France or by French film production companies abroad. It is the oldest and largest precursor of national cinemas in Europe; with primary influ ...

Festival after Cannes in term of visitors, but the first one regarding the number of spectators (in Cannes visitors are not allowed in theatres, only professionals). This festival has revealed many young talented directors now well known in France and internationally such as Mathieu Kassovitz, Cédric Klapisch

Cédric Klapisch ( ; born 4 September 1961) is a French film director, screenwriter and producer.

Life and career

Klapisch was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, Hauts-de-Seine. He is from a Jewish family; his maternal grandparents were deported to Ausc ...

and Éric Zonka.

Beside the short film festival, Clermont-Ferrand hosts more than twenty music, film, dance, theatre and video and digital art festivals every year. With more than 800 artistic groups from dance to music, Clermont-Ferrand and the Auvergne region's cultural life is important in France. One of the city's nicknames is "France's Liverpool". Groups such as The Elderberries and Cocoon were formed there.

Additionally, the city was the subject of the acclaimed documentary ''The Sorrow and the Pity

''The Sorrow and the Pity'' (french: Le Chagrin et la Pitié) is a two-part 1969 documentary film by Marcel Ophuls about the collaboration between the Vichy government and Nazi Germany during World War II. The film uses interviews with a Germ ...

'', which used Clermont-Ferrand as the basis of the film, which told the story of France under Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

occupation and the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

of Marshal Pétain. Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

, Pétain's "handman", was an ''Auvergnat''.

''My Night at Maud's

''My Night at Maud's'' (french: Ma nuit chez Maud), also known as ''My Night with Maud'' (UK), is a 1969 French New Wave drama film by Éric Rohmer. It is the third film (fourth in order of release) in his series of ''Six Moral Tales''.

Over the ...

'' (french: Ma nuit chez Maud), a 1969 French drama film

In film and television, drama is a category or genre of narrative fiction (or semi-fiction) intended to be more serious than humorous in tone. Drama of this kind is usually qualified with additional terms that specify its particular super ...

by Éric Rohmer

Jean Marie Maurice Schérer or Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer, known as Éric Rohmer (; 21 March 192011 January 2010), was a French film director, film critic, journalist, novelist, screenwriter, and teacher.

Rohmer was the last of the post-World ...

, was set and filmed in Clermont-Ferrand in and around Christmas Eve. It is the third film (fourth in order of release) in his series of '' Six Moral Tales''. One of the main themes of the film concerns Pascal's Wager whose author was born in the city in 1623.

The city also hosts '' L'Aventure Michelin'', the museum dedicated to the history of Michelin group.

Sport

Aracing circuit

A race track (racetrack, racing track or racing circuit) is a facility built for racing of vehicles, athletes, or animals (e.g. horse racing or greyhound racing). A race track also may feature grandstands or concourses. Race tracks are also ...

, the Charade Circuit

The Circuit de Charade, also known as Circuit Louis Rosier and Circuit Clermont-Ferrand, is a motorsport race track in Saint-Genès-Champanelle near Clermont-Ferrand in the Puy-de-Dôme department in Auvergne in central France. The circuit, buil ...

, close to the city, using closed-off public road

A highway is any public or private road or other public way on land. It is used for major roads, but also includes other public roads and public tracks. In some areas of the United States, it is used as an equivalent term to controlled-access ...

s held the French Grand Prix

The French Grand Prix (french: Grand Prix de France), formerly known as the Grand Prix de l'ACF (Automobile Club de France), is an auto race held as part of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile's annual Formula One World Championsh ...

in 1965, 1969

This year is notable for Apollo 11's first landing on the moon.

Events January

* January 4 – The Government of Spain hands over Ifni to Morocco.

* January 5

**Ariana Afghan Airlines Flight 701 crashes into a house on its approach to ...

, 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity of X (''Extreme''). Between 10,000 and ...

and 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using mean solar tim ...

. It was a daunting circuit, with such harsh elevation changes that caused some drivers to be ill as they drove. Winners included Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart

Sir John Young Stewart (born 11 June 1939), known as Jackie Stewart, is a British former Formula One racing driver from Scotland. Nicknamed the "Flying Scot", he competed in Formula One between 1965 and 1973, winning three World Drivers' Cha ...

(twice), and Jochen Rindt

Jochen is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Jochen Asche, East German luger, competed during the 1960s

*Jochen Böhler (born 1969), German historian, specializing in the history of World War II

*Jochen Babock (born 1953), East G ...

.

Clermont-Ferrand has some experience in hosting major international sports tournaments such as the FIBA EuroBasket 1999

The 1999 FIBA European Championship, commonly called FIBA EuroBasket 1999, was the 31st FIBA EuroBasket regional basketball championship held by FIBA Europe, which also served as Europe qualifier for the 2000 Olympic Tournament, giving a berth ...

. The city has been the finish of Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

stages in 1951 and 1959, and will host the start of the 2023 Tour de France Femmes

The 2023 Tour de France Femmes, (officially Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift), will be the second edition of the Tour de France Femmes. The race is scheduled for 23 to 30 July 2023, and will be the 21st race in the 2023 UCI Women's World Tour c ...

.

The city is also host to a rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In it ...

club competing at international level, ASM Clermont Auvergne, as well as Clermont Foot Auve rgne, a football club that has competed in France's second division, Ligue 2, since the 2007–08 season. In 2021/22. they will compete in Ligue 1 for the first time in the history of the club.

In the sevens version of rugby union, Clermont-Ferrand has hosted the France Women's Sevens

The France Women's Sevens is an annual women's rugby sevens tournament, and one of the stops on the World Rugby Women's Sevens Series. France joined in the fourth year of the Series. As of the current 2019–20 season, the tournament is held ...

, the final event in each season's World Rugby Women's Sevens Series

The World Rugby Women's Sevens Series, is a series of international rugby sevens tournaments for women's national teams run by World Rugby. The inaugural series was held in 2012–13 as the successor to the IRB Women's Sevens Challenge Cup held ...

, since 2016

File:2016 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: Bombed-out buildings in Ankara following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt; the Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, impeachment trial of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff; Damaged houses duri ...

.

Famous people

Born in Clermont-Ferrand

*

* Avitus

Eparchius Avitus (c. 390 – 457) was Roman emperor of the West from July 455 to October 456. He was a senator of Gallic extraction and a high-ranking officer both in the civil and military administration, as well as Bishop of Piacenza.

He o ...

(ca.385 – ca.456), Roman emperor from the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

from 455 to 456,

* Fadela Amara

Fadela Amara (born Fatiha Amara on 25 April 1964) is a French feminist and politician, who began her political life as an advocate for women in the impoverished ''banlieues''. She was the Secretary of State for Urban Policies in the conservativ ...

(born 1964), feminist and politician

* Martine Blanc (born 1944) an author and illustrator of ten books for children

* Antoine-Jean Bourlin (1752–1828), known as ''Dumaniant

Antoine-Jean Bourlin, better known as Dumaniant, (11 April 1752 – 26 September 1828) was a French comedian, playwright and goguettier.

First a lawyer, he was a comedian in Paris until 1798, then patented entrepreneur of shows in the province. ...

'' a comedian and goguettier.

* Thomas Cailley

Thomas Cailley (born 29 April 1980) is a French screenwriter and film director. In 2014, he made his feature directorial debut with ''Love at First Fight (film), Love at First Fight'', which won three César Awards including César Award for Best ...

(born 1980) a French screenwriter and film director.

* Nicolas Chamfort

Sébastien-Roch Nicolas, known in his adult life as Nicolas Chamfort and as Sébastien Nicolas de Chamfort (; 6 April 1741 – 13 April 1794), was a French writer, best known for his epigrams and aphorisms. He was secretary to Louis XVI's siste ...

(1741–1794), writer of epigrams

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two millen ...

and aphorisms.

* Étienne Clémentel

Étienne Clémentel (11 January 1864 – 25 December 1936) was a French politician. He served as a member of the National Assembly of France from 1900 to 1919 and as French Senator from 1920 to 1936. He also served as Minister of Colonies from 2 ...

(1864– 1936), politician, Govt. Minister and painter

* Cécile Coulon (born 1990) novelist, poet and short story writer.

* Jacques Delille

The French poet Jacques Delille (; 22 June 1738 at Aigueperse in Auvergne – 1 May 1813, in Paris) came to national prominence with his translation of Virgil’s Georgics and made an international reputation with his didactic poem on gardening. ...

(1738 in Aigueperse – 1813), translated Virgil’s Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

and wrote a didactic poem on gardening.

* Lolo Ferrari (1963–2000), dancer, actress and singer with very large breast implants

* Gregory of Tours (ca.538 – 594) a Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

historian and Bishop of Tours

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tours ( Latin: ''Archidioecesis Turonensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Tours'') is an archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The archdiocese has roots that go back to the 3rd c ...

.

* Ginette Hamelin

Ginette Hamelin (4 March 1913 – 14 October 1944) was a French engineer and architect who became a member of the French Resistance and an intelligence officer in WWII. She was murdered in a concentration camp in 1944.

Biography

Hamelin was born ...

(1913–1944), French engineer and architect; member of the French resistance; died in a concentration camp

* Annelise Hesme

Annelise Hesme (born 11 May 1976) is a French actress. Her older sister Élodie Hesme and younger sister Clotilde Hesme are also actresses.

Born in Beaumont, Puy-de-Dôme, Auvergne, France.

Hesme has appeared in many films such as '' Tanguy'' ...

(born 1976), actress and plays the cello and the piano.

* Thierry Laget (born 1959), writer, winner of the 1992 Prix Fénéon

The Fénéon Prize (''Prix Fénéon''), established in 1949, is awarded annually to a French-language writer and a visual artist no older than 35 years of age. The prize was established by Fanny Fénéon, the widow of French art critic Félix Fén� ...

* Edmond Lemaigre (1849–1890), composer and organist

* Antoine de Lhoyer

Antoine de Lhoyer 'Hoyer(6 September 1768 – 15 March 1852) was a French virtuoso classical guitarist and an eminent early romantic composer of mainly chamber music featuring the classical guitar. Lhoyer also had a notable military career; he ...

(1768–1852), composer, guitarist and soldier

* Bernard Loiseau

Bernard Daniel Jacques Loiseau (, 13 January 1951 – 24 February 2003) was a French chef at Le Relais Bernard Loiseau in Saulieu. He obtained his three stars in the Michelin Guide, and had a peak rating of 19.5/20 in the Gault Millau restaura ...

(1951– 2003), celebrity chef

* François-Bernard Mâche

François-Bernard Mâche (born 4 April 1935, Clermont-Ferrand) is a French composer of contemporary music.

Biography

Born into a family of musicians, he is a former student of Émile Passani and Olivier Messiaen and has also received a diplom ...

(born 1935), composer of contemporary music.

* Antoine François Marmontel

Antoine François Marmontel () (18 July 1816 – 16 January 1898) was a French pianist, composer, teacher and musicographer. He is mainly known today as an influential teacher at the Paris Conservatory, where he taught many musicians who became ...

(1816–1898) pianist and teacher at the Paris Conservatory

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

* Léon Melchissédec

Léon Melchissédec (born Clermont Ferrand, 7 May 1843, died Neuilly-sur-Seine 23 March 1925) was a French baritone who enjoyed a long career in the French capital across a broad range of operatic genres, and later made some recordings and also ...

(1843-1925) baritone and teacher at the Paris Conservatory

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

* André Michelin

André Jules Michelin (16 January 1853 – 4 April 1931) was a French industrialist who, with his brother Édouard (1859–1940), founded the Michelin Tyre Company (''Compagnie Générale des Établissements Michelin'') in 1888 in the French ...

(1853–1931) and Édouard Michelin (1859–1940), creators of the Michelin tyre group whose global headquarters are still located in Clermont-Ferrand

* Léonard Morel-Ladeuil (1820-1888), goldsmith and sculptor.

* George Onslow George Onslow may refer to:

*George Onslow (British Army officer) (1731–1792), British politician and army officer

*George Onslow, 1st Earl of Onslow (1731–1814), British peer and politician

*George Onslow (composer)

André George(s) Louis ...

(1784–1853), composer, mainly of chamber music

* Victor Pachon (1867–1938), physiologist, worked on blood pressure

* Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), mathematician, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, and religious philosopher.

* Jacqueline Pascal

Jacqueline Pascal (4 October 1625 – 4 October 1661), sister of Blaise Pascal, was born at Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne (region), Auvergne, France.

Like her brother she was a prodigy, composing verses when only eight years old, and a five-act com ...

(1625–1661) child prodigy, composed verses, sister of Blaise Pascal.

* Dominique Perrault

Dominique Perrault (born 9 April 1953 in Clermont-Ferrand) is a French architect and urban planner. He became world known for the design of the French National Library, distinguished with the Silver medal for town planning in 1992 and the Mies v ...

(born 1953), architect, designed the French National Library

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

* Henri Pognon (1853–1921), epigrapher, archaeologist and diplomat

* Henri Quittard

Henri Quittard (16 May 1864 – 21 July 1919) was a French composer, musicologist and music critic.

Biography

A musician, composer, musicologist and music critic, Quittard was both the cousin of Emmanuel Chabrier (Quittard being the grandson ...

(1864–1919), composer, musicologist and music critic.

* François Dominique de Reynaud, Comte de Montlosier

François Dominique de Reynaud, Comte de Montlosier (April 16, 1755 in Clermont-Ferrand – December 9, 1838), was a notable French politician and political writer during the First French Empire, Bourbon Restoration and July Monarchy. He was the y ...

(1755–1838), politician and political writer.

* Peire Rogier

Peire Rogier (born c. 1145) was a twelfth-century Auvergnat troubadour (fl. 1160 – 1180) and cathedral canon from Clermont. He left his cathedral to become a travelling minstrel before settling down for a time in Narbonne at the court of the ...

(born ca.1145) an Auvergnat troubadour (fl. 1160 – 1180) and cathedral canon

* Audrey Tautou (born 1976), actress and model

* Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and phil ...

(1881–1955), philosopher, Jesuit priest

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

and paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Sport

* Chakir Ansari (born 1991), Moroccan freestyle wrestler, competed at the 2016 Summer Olympics

*

* Chakir Ansari (born 1991), Moroccan freestyle wrestler, competed at the 2016 Summer Olympics

* Laure Boulleau

Laure Pascale Claire Boulleau (born 22 October 1986) is a French former footballer who played for the Division 1 Féminine club Paris Saint-Germain (PSG). She primarily played as a defender and was a member of the France women's national football ...

(born 1986), footballer with 216 club caps and 65 for France women

* Patrick Depailler

Patrick André Eugène Joseph Depailler (; 9 August 1944 – 1 August 1980) was a racing driver from France. He participated in 95 World Championship Formula One Grands Prix, debuting on 2 July 1972. He also participated in several non-champi ...

(1944–1980), Formula One

Formula One (also known as Formula 1 or F1) is the highest class of international racing for open-wheel single-seater formula racing cars sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The World Drivers' Championship, ...

driver

* Yves Dreyfus

Yves Dreyfus (17 May 1931 – 16 December 2021) was a French epee fencer who held two medals as part of the French Olympic épée team.

Life and career

Dreyfus was born in Clermont-Ferrand, France, and was Jewish. He survived the Nazi occupati ...

(1931–2021) epee fencer, bronze medalist at the 1956 Summer Olympics,

* Raphaël Géminiani

Raphaël Géminiani (born Clermont-Ferrand; born 12 June 1925) is a French former road bicycle racer. He had six podium finishes in the Grand Tours. He is one of four children of Italian immigrants who moved to Clermont-FerrandColin, Jacques ( ...

(born 1925) a French former road bicycle racer.

* Jordan Lotiès (born 1984), footballer with 370 club caps

* Émile Mayade (1853–1898), a motoring pioneer and racing driver.

* Darline Nsoki (born 1989), basketball player

* Gabriella Papadakis

Gabriella Maria Papadakis (born 10 May 1995) is a French ice dancer. With her partner, Guillaume Cizeron, she is a 2022 Olympic champion, 2018 Olympic silver medalist, a five-time World champion (2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2022), a five-time con ...

(born 1995), ice dancer, Olympic medallist & World and European champion

* Émile Pladner

Émile Pladner (2 September 1906 – 15 March 1980) was a French people, French Boxing, boxer who was flyweight champion of France, Europe, and the world, and bantamweight champion of France and Europe.

Career

Born in Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dô ...

(1906–1980) flyweight champion boxer, 104 wins, 16 losses and 13 draws.

* Aurélien Rougerie (born 1980), rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In it ...

player, with 417 club caps and 47 for France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

* Christian Sarron

Christian Sarron (born 27 March 1955 in Clermont-Ferrand, France) is a French former Grand Prix motorcycle road racer.

__TOC__

Motorcycle racing career

He began his career on a Kawasaki when he met French Grand Prix racer Patrick Pons. Pons ...

(born 1955), Grand Prix motorcycle road racer

* Gauthier de Tessières

Gauthier de Tessières (born 9 November 1981) is a World Cup alpine ski racer from France, and has competed in two Winter Olympics and five World Championships. He made his breakthrough on the Alpine Skiing World Cup in a giant slalom in Val-d'I ...

(born 1981) a World Cup alpine ski racer

Resident in Clermont-Ferrand

*

* Sidonius Apollinaris

Gaius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius, better known as Sidonius Apollinaris (5 November of an unknown year, 430 – 481/490 AD), was a poet, diplomat, and bishop. Sidonius is "the single most important surviving author from 5th-century Gaul ...

(ca.430–after 489), Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

poet, diplomat and bishop.

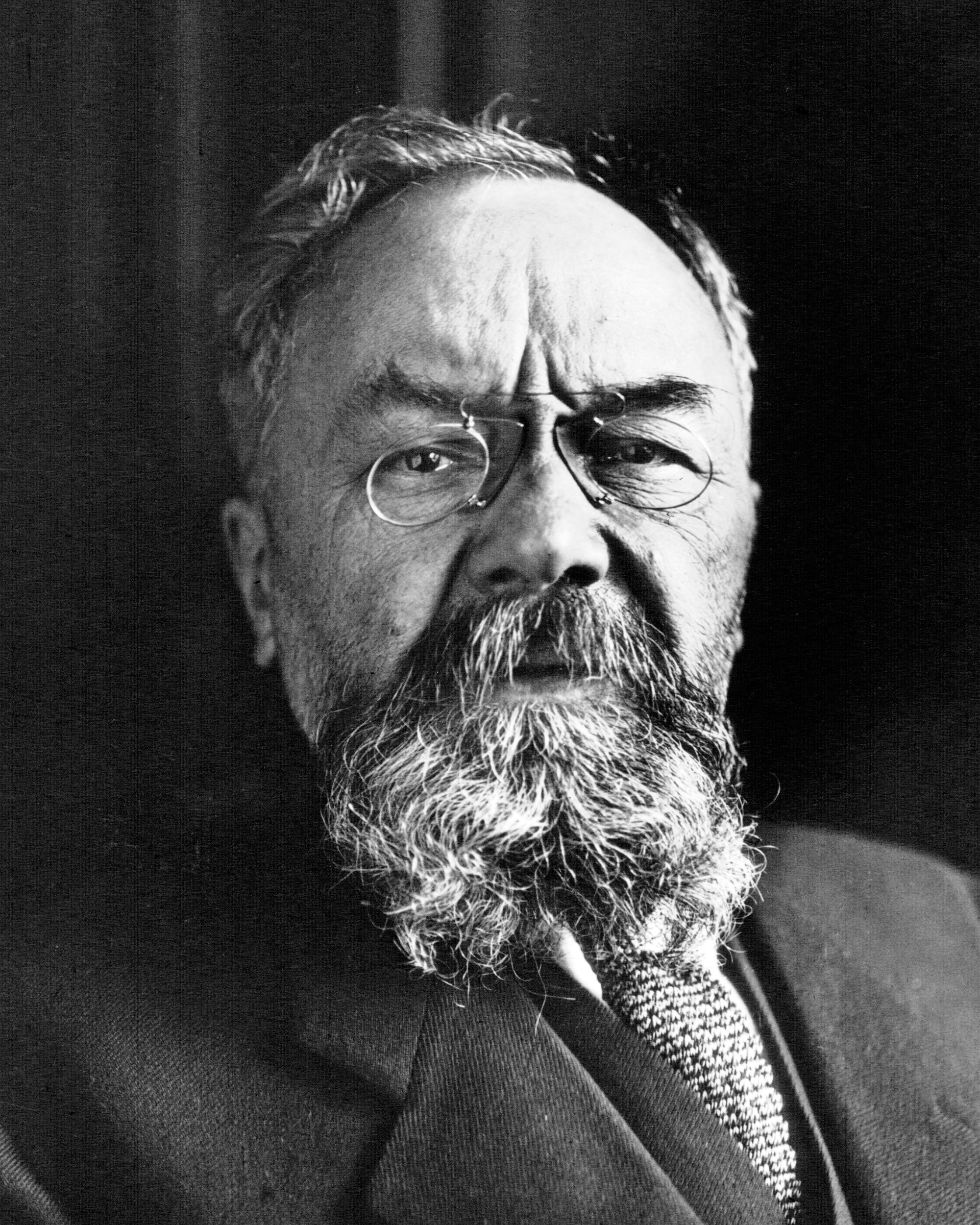

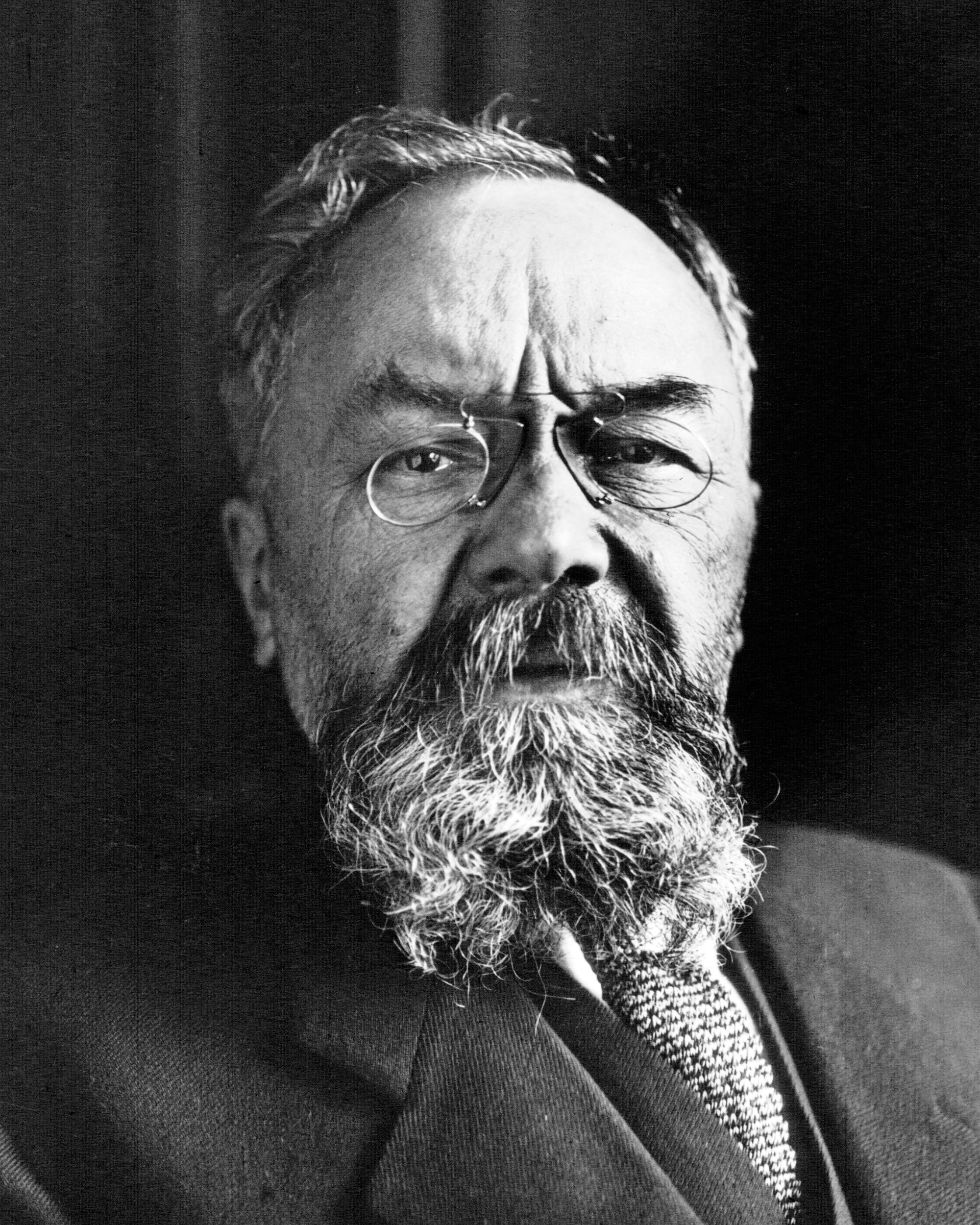

* Henri Bergson (1859–1941), philosopher

* Olivier Bianchi

Olivier Bianchi (born June 10, 1970, in Paris) is a French politician. A member of the Socialist Party (France), Socialist Party, he has been mayor of Clermont-Ferrand since April 4, 2014 and president of Clermont Auvergne Métropole since April 2 ...

(born 1970) politician and Mayor of Clermont-Ferrand since 2014

* Paul Bourget

Paul Charles Joseph Bourget (; 2 September 185225 December 1935) was a French poet, novelist and critic. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature five times.

Life

Paul Bourget was born in Amiens in the Somme ''département'' of Picar ...

(1852–1935), novelist and critic.

* Ivor Bueb

Ivor Léon John Bueb (6 June 1923 – 1 August 1959) was a British professional sports car racing and Formula One driver from England.

Career

Born in East Ham, Essex east of London, Bueb started racing seriously in a Formula Three 500cc Cooper ...

(1923–1959) was a British professional sports car racing and Formula One

Formula One (also known as Formula 1 or F1) is the highest class of international racing for open-wheel single-seater formula racing cars sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The World Drivers' Championship, ...

driver.

* Anton Docher

Anton Docher (1852–1928), born Antonin Jean Baptiste Docher (pronounced ɑ̃tɔnɛ̃ ʒɑ̃ batist dɔʃe), was a French Franciscan Roman Catholic priest, who served as a missionary to Native Americans in New Mexico, in the Southwest of t ...

(1852–1928) "The Padre of Isleta", Roman Catholic priest, missionary and defender of the Indians lived in the pueblo of Isleta in the state of New Mexico for 34 years

* Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

(1927-2020), lived in the city of Chamalières part of Clermont-Ferrand's metropolitan area, President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

from 1974 to 1981

* Claude Lanzmann

Claude Lanzmann (; 27 November 1925 – 5 July 2018) was a French filmmaker known for the Holocaust documentary film '' Shoah'' (1985).

Early life

Lanzmann was born on 27 November 1925 in Paris, France, the son of Paulette () and Armand Lanzmann. ...

(1925–2018), film maker, attended the Lycée Blaise-Pascal

Education

Education is also an important factor in the economy of Clermont-Ferrand. The University of Clermont Auvergne (formed in 2017 from a merger of Université Blaise Pascal andUniversité d'Auvergne

The University of Auvergne (Université d'Auvergne), also known as “Universite d'Auvergne Clermont-Ferrand I” or Clermont-Ferrand I, was a French public university, based in Clermont-Ferrand, in the region of Auvergne. It was under the Academ ...

) is located there and has a total student population of over 37,000, along with university faculty and staff.

With around 1,000 students SIGMA Clermont is the biggest engineering graduate school in the city.

A division of Polytech (an engineering school) located in Clermont-Ferrand made the news because two of its students, Laurent Bonomo and Gabriel Ferez, were murdered in June 2008 while enrolled in a program at Imperial College in London in what was to be known as the New Cross double murder

The New Cross double murder occurred on 29 June 2008. Two French research students, Laurent Bonomo and Gabriel Ferez, were stabbed to death in New Cross, London Borough of Lewisham in South East London, United Kingdom.

Murders

The victims were ...

.

The ESC Clermont Business School

ESC Clermont Business School is a business school located in France, in the city of Clermont-Ferrand. Established in 1919, the school of management is a Grande Ecole that is recognized by The French Ministry of Higher Education and Research. The ...

, created in 1919, is also located in the city.

Twin towns - sister cities

Clermont-Ferrand is twinned with: *Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, Scotland, United Kingdom (since 1983)

* Braga

Braga ( , ; cel-x-proto, Bracara) is a city and a municipality, capital of the northwestern Portuguese district of Braga and of the historical and cultural Minho Province. Braga Municipality has a resident population of 193,333 inhabitants (in ...

, Portugal

* Gomel

Gomel (russian: Гомель, ) or Homiel ( be, Гомель, ) is the administrative centre of Gomel Region and the second-largest city in Belarus with 526,872 inhabitants (2015 census).

Etymology

There are at least six narratives of the o ...

, Belarus

* Norman, Oklahoma

Norman () is the third-largest city in the U.S. state of Oklahoma, with a population of 128,097 as of 2021. It is the largest city and the county seat of Cleveland County, and the second-largest city in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area, b ...

, United States

* Oviedo, Spain

* Regensburg, Germany (since 1969)

* Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, England, United Kingdom

See also

*Communes of the Puy-de-Dôme department

The following is a list of the 464 communes of the Puy-de-Dôme department of France.

Intercommunalities

The communes cooperate in the following intercommunalities (as of 2020):Jaude Centre

*

Town hall website

Tourist office

Unofficial Clermont-Ferrand website

– Translation by Allen Williamson of an entry concerning Joan of Arc's letter to this city on 7 November 1429. {{DEFAULTSORT:Clermontferrand Communes of Puy-de-Dôme Massif Central Prefectures in France Cities in France Gallia Aquitania Auvergne

List of works by Auguste Carli

Auguste Carli was born on July 12, 1868 in Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, and many of his works can be seen in Marseille itself and in the Bouches-du-Rhône

Bouches-du-Rhône ( , , ; oc, Bocas de Ròse ; "Mouths of the Rhône") is a departme ...

*List of twin towns and sister cities in France

This is a list of municipalities in France which have standing links to local communities in other countries known as "town twinning" (usually in Europe) or "sister cities" (usually in the rest of the world).

A Ab–Am

Abbeville

* Argos, ...

References

Bibliography

*External links

Town hall website

Tourist office

Unofficial Clermont-Ferrand website

– Translation by Allen Williamson of an entry concerning Joan of Arc's letter to this city on 7 November 1429. {{DEFAULTSORT:Clermontferrand Communes of Puy-de-Dôme Massif Central Prefectures in France Cities in France Gallia Aquitania Auvergne