Christopher Nugent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Christopher Nugent, 6th (or 14th)

Delvin was the author of:

1. ''A Primer of the Irish Language, compiled at the request and for the use of Queen Elizabeth.'' It is described by

Delvin was the author of:

1. ''A Primer of the Irish Language, compiled at the request and for the use of Queen Elizabeth.'' It is described by

Baron Delvin

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often Hereditary title, hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher th ...

(1544–1602) was an Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

nobleman and writer. He was arrested on suspicion of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

against Queen Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

, and died while in confinement before his trial had taken place.

Family and early years

He was the eldest son of Richard, 5th (or 13th) Baron Delvin, and Elizabeth, daughter of Jenico Preston, 3rdViscount Gormanston

Viscount Gormanston is a Peerage, title in the Peerage of Ireland created in 1478 and held by the head of the Preston family, which hailed from Lancashire. It is the oldest Viscount, vicomital title in the British Isles; the holder is Premier Vi ...

, and widow of Thomas Nangle, styled Baron of Navan {{Use dmy dates, date=November 2019

The Barony of Navan was an Irish feudal barony which was held by the de Angulo family, whose name became Nangle. It was a customary title: in other words, the holder of the title was always referred to as a Baron, ...

. Richard Nugent, fourth or twelfth Baron Delvin, was his great-grandfather. He succeeded to the title on the death of his father, on 10 December 1559, and during his minority was the ward of Thomas Ratcliffe, third earl of Sussex, for whom he conceived a great friendship.

He was matriculated a fellow commoner of Clare Hall, Cambridge

Clare Hall is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. Founded in 1966 by Clare College, Clare Hall is a college for advanced study, admitting only postgraduate students alongside postdoctoral researchers and fellows. It ...

, on 12 May 1563, and was presented to the queen when she visited the university in 1564; on coming of age, about November 1565, he repaired to Ireland, with letters of commendation from the queen to the lord deputy, Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he received ...

, granting him the lease in reversion of the abbey of All Saints and the custody of Sleaught-William in the Annaly, County Longford

County Longford ( gle, Contae an Longfoirt) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was 46,6 ...

.

As an undertaker in the plantation of County Laois

County Laois ( ; gle, Contae Laoise) is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and in the province of Leinster. It was known as Queen's County from 1556 to 1922. The modern county takes its name from Loígis, a medie ...

and County Offaly

County Offaly (; ga, Contae Uíbh Fhailí) is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is named after the ancient Kingdom of Uí Failghe. It was formerly known as King's County, in hono ...

, he had previously obtained, on 3 February 1563–64, a grant of the castle and lands of Corbetstown, alias Ballycorbet, in Offaly (then known as King's County): land confiscated from Garret FitzGerald. In the autumn of the following year, he distinguished himself against Shane O'Neill, and was knighted at Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

by Sidney. On 30 June 1567 he obtained a lease of the abbey of Inchmore in the Annaly and the abbey of Fore in County Westmeath

"Noble above nobility"

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Westmeath.svg

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state, Country

, subdivision_name = Republic of Ireland, Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Provinces o ...

, to which was added on 7 October the lease of other lands in the same county.

Suspicions of disloyalty and treason

In July 1574 his refusal, with his cousin Christopher,Viscount Gormanston

Viscount Gormanston is a Peerage, title in the Peerage of Ireland created in 1478 and held by the head of the Preston family, which hailed from Lancashire. It is the oldest Viscount, vicomital title in the British Isles; the holder is Premier Vi ...

, to sign the proclamation of rebellion against the Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond is a title in the peerage of Ireland () created four times. When the powerful Earl of Desmond took arms against Queen Elizabeth Tudor, around 1578, along with the King of Spain and the Pope, he was confiscated from his estates, s ...

laid his loyalty open to suspicion, given the tone of the recent papal bull ''Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared h ...

''. He grounded his refusal on the fact that he was not a privy councillor, and had not been made acquainted with the reasons for the proclamation. The English Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, thinking that his objections savoured more of 'a wilful partiality to an offender against her majesty than a willing readiness to her service', sent peremptory orders for his submission. Fresh letters of explanation were proffered by him and Gormanston in February 1575, but, being deemed insufficient, the two noblemen were in May placed under restraint. They thereupon confessed their 'fault', and Delvin shortly afterwards appears to have recovered the good opinion of government: for on 15 December the Lord-Deputy Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he received ...

wrote that he expected a speedy reformation of the country, 'a great deal the rather through the good hope I conceive of the service of my lord of Delvin, whom I find active and of good discretion'; and in April 1576 Delvin entertained Sidney while on progress.

Before the end of the year, however, there sprang up a controversy between the government and the gentry of the Pale

The Pale (Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast st ...

in regard to cess, in which Delvin played a principal part. It had long been the custom of the Anglo-Irish government to support the army, to take up provisions, etc., at a fixed price. This custom, called "cess", was considered unfair by the inhabitants of the Pale. In 1576, at the instigation chiefly of Delvin, they denounced the custom as unconstitutional, and appointed three of their number, all leading barristers

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

, to lay their grievances before the queen. The deputation met with scant courtesy in England. Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

was indignant at having her royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

called in question, and, after roundly abusing the deputies for their impertinence, sent them to the Fleet Prison. In Ireland Delvin, Baltinglas, and others were confined in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the se ...

in May 1577. After some weeks' detention, the deputies and their principals were released after expressing contrition for their conduct. But with Delvin, 'for that he has showed himself to be the chiefest instrument in terrifying and dispersuading the rest of the associates from yielding their submission', Elizabeth left it to Sidney's discretion whether he should remain in prison for some time longer. Finally, an arrangement was arrived at between the government and the gentry of the Pale

The Pale (Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast st ...

.

In the autumn of 1579, Delvin was entrusted with the command of the forces of the Pale, and was reported to have done good service in defending the northern marches against Turlough Luineach O'Neill

Sir Turlough Lynagh O'Neill (Irish: ''Sir Toirdhealbhach Luineach mac Néill Chonnalaigh Ó Néill''; 1532 – September, 1595) was an Irish Gaelic lord of Tír Eoghain in early modern Ireland. He was inaugurated upon Shane O’Neill’s death, ...

. His 'obstinate affection to popery', however, told in his disfavour, and it was as much for this general reason as for any proof of treason that the Anglo-Irish government, in December 1580, committed him, along with his father-in-law, Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare

Gerald is a male Germanic given name meaning "rule of the spear" from the prefix ''ger-'' ("spear") and suffix ''-wald'' ("rule"). Variants include the English given name Jerrold, the feminine nickname Jeri and the Welsh language Gerallt and Iri ...

, to Dublin Castle on suspicion of being implicated in the rebellious projects of Viscount Baltinglas. The higher officials, including Lord-Deputy Grey de Wilton, were convinced of his treason, but they were unable to establish their charge against him. After an imprisonment of 18 months, he and FitzGerald were sent to England in the custody of Marshal Henry Bagenal

Sir Henry Bagenal PC (c. 1556 – 14 August 1598) was marshal of the Royal Irish Army during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Life

He was the eldest son of Nicholas Bagenal and Eleanor Griffith, daughter of Sir Edward Griffith of Penrhyn. His br ...

.

In Dublin, the Nugent family's enemies, notably the Dillons, moved against his relatives. His uncle Nicholas Nugent

Nicholas Nugent (c. 1525–1582) was an Anglo-Irish judge, who was hanged for treason by the government that appointed him. He had, before his downfall, enjoyed a highly successful career, holding office as Solicitor General for Ireland, Baron of ...

, the Chief Justice of the Irish Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas for Ireland was the presiding judge of the Court of Common Pleas in Ireland, which was known in its early years as the Court of Common Bench, or simply as "the Bench", or "the Dublin bench". It was one of the s ...

, was suspended from office, tried for treason and hanged. Delvin's younger brother William Nugent

William Nugent (Irish: ''Uilliam Nuinseann'') (1550–1625) was a Hiberno-Norman rebel in the 16th century Kingdom of Ireland, brother of Christopher, fourteenth baron of Delvin (Sixth Baron Delvin), and the younger son of Richard Nugent, ...

was driven into rebellion but eventually obtained a pardon.

On 22 June 1582, Delvin was examined by Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Walter Mildmay (bef. 1523 – 31 May 1589) was a statesman who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I, and founded Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Origins

He was born at Moulsham in Essex, the fourth and youngest son of Th ...

and Gerard

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful constituents put together. In this ca ...

, Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Court of Appeal (England and Wales)#Civil Division, Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales a ...

. No fresh evidence of his treason was adduced, and Henry Wallop

Sir Henry Wallop (c. 1540 – 14 April 1599) was an English statesman.

Biography

Henry Wallop was the eldest son of Sir Oliver Wallop (d. 1566) of Farleigh Wallop in Hampshire. Having inherited the estates of his father and of his uncle, Sir Joh ...

heard with alarm that it was intended to set him at liberty.

In April 1585 he was again in Ireland, sitting as a peer in parliament. During the course of the year, he was again in England; but after the death, on 16 November 1585, of the Earl of Kildare he was allowed to return to Ireland, 'in the company of the new Earl of Kildare

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

, partly for the execution of the will of the earl, his father-in-law, partly to look into the estates of his own lands, from whence he hath been so long absent'. He carried letters of commendation to the new lord deputy, Sir John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) served as lord deputy to Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, though the idea is reject ...

; and the queen, 'the better to express her favour towards him,' granted him a renewal of the leases he held from the crown.

He was under obligations to return to England as soon as he had transacted his business. But during his absence many lawsuits pertaining to his lands had arisen, and, owing to the hostility of Sir Robert Dillon, Chief Justice of the Irish Common Pleas, and Chief Baron Sir Lucas Dillon, his hereditary enemies, he found it difficult to put the law in motion.

He seems to have returned to England in 1587, and, having succeeded in securing the favour of Elizabeth's spymaster William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1 ...

, he was allowed in October 1588 to return to Ireland.

New Lord Deputy Sir William Fitzwilliam wrote to Burghley that he hoped that Delvin would "throughly performe that honorable and good opynion it hath pleased yr Lp. to conceave of him, wch no doubt he may very sufficiently do, and wth all do her matie great service in action, both cyvill and martiall, if to the witt wherewth God hath indued him and the loue and liking wherewth the countrey doth affect him, he applie him self wth his best endevor." He included Delvin in his list of 'doubtful men in Ireland.'

One cause that told greatly in his disfavour was his extreme animosity to Robert Dillon, who he regarded as having done to death his uncle Nicholas Nugent. To Burghley, who warned him that he was regarded with suspicion, he protested his loyalty and readiness to quit all that was dear to him in Ireland and live in poverty in England, rather than that the queen should conceive the least thought of undutifulness in him. He led, he declared, an orderly life, avoiding discontented society, every term following the law in Dublin for the recovery of his lands, and serving the queen at the assizes in his own neighbourhood. The rest of his time he spent in books and building.

The violence with which he prosecuted Chief Justice Dillon afforded ground to his enemies to describe him as a discontented and seditious person, especially when, after the acquittal of Dillon, he charged the Lord Deputy with having acted with undue partiality.

However, in 1593 he was appointed leader of the forces of Westmeath at the general hosting on the hill of Tara

The Hill of Tara ( ga, Teamhair or ) is a hill and ancient ceremonial and burial site near Skryne in County Meath, Ireland. Tradition identifies the hill as the inauguration place and seat of the High Kings of Ireland; it also appears in Iri ...

, and during the disturbed period (1593–7) that preceded the rebellion of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, he displayed great activity in his defence of the Pale. He was commended for his zeal by Sir John Norris.

He obtained permission to visit England in 1597, and in consequence of his recent chargeable and valourous services, he was, on 7 May, ordered a grant of so much of the O'Farrells' and O'Reillys' lands as amounted to an annual rent to the crown of 100/, though the warrant was never executed during his lifetime.

On 20 May he was appointed a commissioner to inquire into abuses in the government of Ireland. On 17 March 1598, a commission (renewed on 3 July and 30 October) was issued to him and Edward Nugent of the Dísert to deliver the gaol of Mullingar by martial law, for 'that the gaol is now very much pestered with a great number of prisoners, the most part whereof are poor men ... and that there can be no sessions held whereby the prisoners might receive their trial by ordinary course of law'. On 7 August 1599 he was granted the wardship of his grandson, Christopher Chevers, with a condition that he should cause his ward 'to be maintained and educated in the English religion, and in English apparel, in the college of the Holy Trinity, Dublin'; in November he was commissioned by the Earl of Ormonde to hold a parley with the Earl of Tyrone.

On the outbreak of Tyrone's rebellion, the extreme severity with which his country was treated by Tyrone on his march into Munster early in 1600 induced Delvin to submit to him; and, though he does not appear to have rendered him any active service, he was shortly afterwards arrested on suspicion of treason by the current Lord Deputy, Mountjoy, and imprisoned again in Dublin Castle. He died in the castle before his trial, apparently on 17 August 1602, though by another account on 5 September or 1 October, and was buried at Castle Delvin on 5 October.

Marriage and issue

Delvin married Lady Mary FitzGerald, daughter of Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare, andMabel Browne

Mabel Browne, Countess of Kildare (c. 1536 – 25 August 1610) was an English courtier. She was wife of Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare, Baron of Offaly (25 February 1525 – 16 November 1585). She was born into the English Roman Catholi ...

; she died on 1 October 1610. His and Mary's children were:

* Richard Nugent, 1st Earl of Westmeath

Richard Nugent, 1st Earl of Westmeath (1583–1642) was an Irish nobleman and politician of the seventeenth century. He was imprisoned for plotting against the English Crown in 1607, but soon obtained a royal pardon, and thereafter was, in gener ...

(1583–1642)

* Christopher of Corbetstown, who married Anne, daughter of Edward Cusack of Lismullen, and widow of Sir Ambrose Forth

Sir Ambrose Forth (c.1545-1610) was an English-born civilian lawyer whose career was spent in Ireland, where he became the Irish Probate judge and later the first judge of the Irish Court of Admiralty. He has been praised as a diligent, conscient ...

, judge of the Irish Court of Admiralty

Admiralty courts, also known as maritime courts, are courts exercising jurisdiction over all maritime contracts, torts, injuries, and offences.

Admiralty courts in the United Kingdom England and Wales

Scotland

The Scottish court's earliest ...

; he was dead by 1637, when Anne was described as the wife of Valerian Wellesley

* Gerald

* Thomas

* Gilbert

* William

* Mabel, who married, first, Murrough McDermot O'Brien, 3rd Baron Inchiquin

Murrough McDermot O'Brien (c.1550 - 20 April 1573) was the 3rd Baron Inchiquin. He was the son of Dermod O'Brien, 2nd Baron Inchiquin and Margaret O'Brien and inherited his title in 1557 on the death of his father.

He married Margaret Cusack, ...

, then John Fitzpatrick, second son of Florence Fitzpatrick, Baron Upper Ossory

Baron Upper Ossory was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 11 June 1541 for Barnaby Fitzpatrick. This was in pursuance of the Surrender and regrant policy of King Henry VIII. Under the policy, Gaelic chiefs were actively encou ...

* Elizabeth, who married Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Kildare

Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Kildare (died 11 February 1612) was an Irish Peerage, peer. Much of his adult life was dominated by litigation with relatives over the Kildare inheritance.

Background

Lord Kildare was the son of Edward FitzGerald, ...

* Mary, first wife of Anthony (or Owny) O'Dempsey, heir-apparent to Terence O'Dempsey, 1st Viscount Clanmalier

* Eleanor, wife of Christopher Chevers of Macetown, County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the sou ...

* Margaret, who married a Fitzgerald

* Juliana, second wife of Sir Gerald Aylmer, 1st Baronet, of Donade, County Kildare

County Kildare ( ga, Contae Chill Dara) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the county, ...

.

Works

Delvin was the author of:

1. ''A Primer of the Irish Language, compiled at the request and for the use of Queen Elizabeth.'' It is described by

Delvin was the author of:

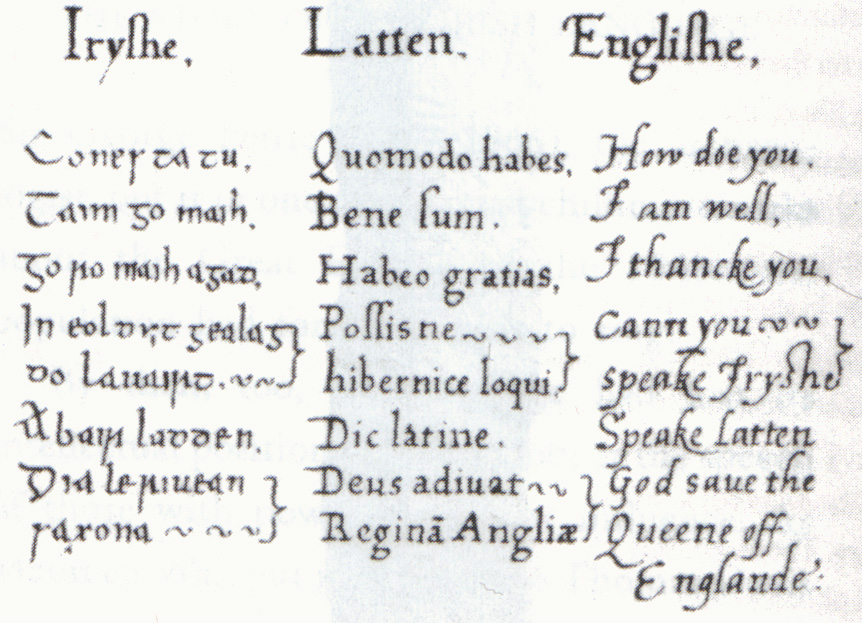

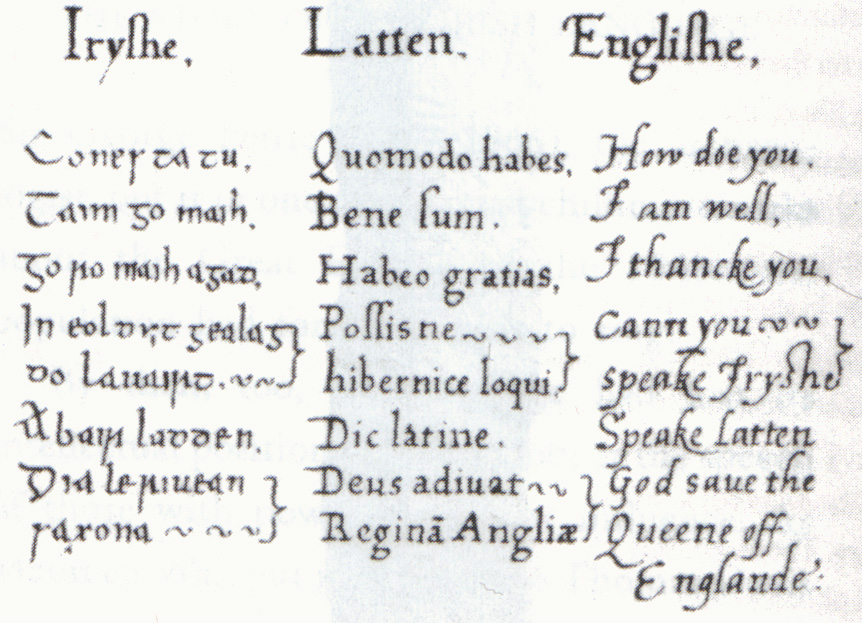

1. ''A Primer of the Irish Language, compiled at the request and for the use of Queen Elizabeth.'' It is described by John Thomas Gilbert

Sir John Thomas Gilbert, LLD, FSA, RIA (born 23 January 1829, Dublin - died 23 May 1898, Dublin) was an Irish archivist, antiquarian and historian.

Life

John Thomas Gilbert was the second son of John Gilbert, an English Protestant, who was Por ...

as a 'small and elegantly written volume,' consisting of 'an address to the queen in English, an introductory statement in Latin, followed by the Irish alphabet, the vowels, consonants, and diphthongs, with words and phrases in Irish, Latin, and English.'

2. ''A Plot for the Reformation of Ireland'', which, though short, is not without interest, as expressing the views of what may be described as the moderate or constitutional party in Ireland as distinct from officialdom on the one hand, and the Irish on the other. He writes that the viceroy's authority is too absolute; that the institution of presidents of provinces is unnecessary; that justice is not administered impartially; that the people are plundered by a beggarly soldiery, who find it in their interest to create dissensions; that the prince's word is pledged recklessly and broken shamelessly, and, above all, that there is no means of education such as is furnished by a university provided for the gentry, "in myne opynion one of the cheifest causes of mischeif in the realme."Preserved in 'State Papers,' Ireland, Eliz. cviii. 38, and printed by Mr. J. T. Gilbert in ''Account of National MSS. of Ireland,'' pp. 189–95.

Sources

This incorporates the article by Robert Dunlop in the old DNB, who used the following sources: *''Lodge's Peerage'', ed. Mervyn Archdall, i. 233-7; * Charles Henry Cooper, ''Athenae Cantabr.''. ii. 331-3, and authorities there quoted; *''Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, Eliz.''; *''Cal. Carew MSS.''; * Morrin's ''Cal. Patent Rolls, Eliz.''; *''Cal. Fiants, Eliz.''; *''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

'', ed. O'Donovan;

*''Annals of Loch Cé'', ed. Hennessy;

*Fynes Moryson

Fynes Moryson (or Morison) (1566 – 12 February 1630) spent most of the decade of the 1590s travelling on the European continent and the eastern Mediterranean lands. He wrote about it later in his multi-volume ''Itinerary'', a work of value to ...

, ''Itinerary'';

*Stafford's ''Pacata Hibernia'';

*Gilbert's ''Facsimiles of National MSS. of Ireland'', iv. 1;

*Richard Bagwell

Richard Bagwell (9 December 1840 – 4 December 1918) was a noted historian of the Stuart and Tudor periods in Ireland, and a political commentator with strong Unionist convictions.

He was the eldest son of John Bagwell, M.P. for Clonmel from ...

, ''Ireland under the Tudors''.

Also see:

*

*

*David Mathew, ''The Celtic peoples and renaissance Europe'' (London, 1933).

*Helen Coburn-Walsh ''The rebellion of William Nugent'' in R. V. Comerford (ed.) ''Religion, Conflict and co-existence in Ireland'' (Dublin, 1990).

Notes

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Nugent, Christopher 1544 births 1602 deaths People from County Westmeath 16th-century Irish people People of Elizabethan Ireland 17th-century Irish people Latin–English translators Delvin, Christopher Nudent, Baron