Christopher Love on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

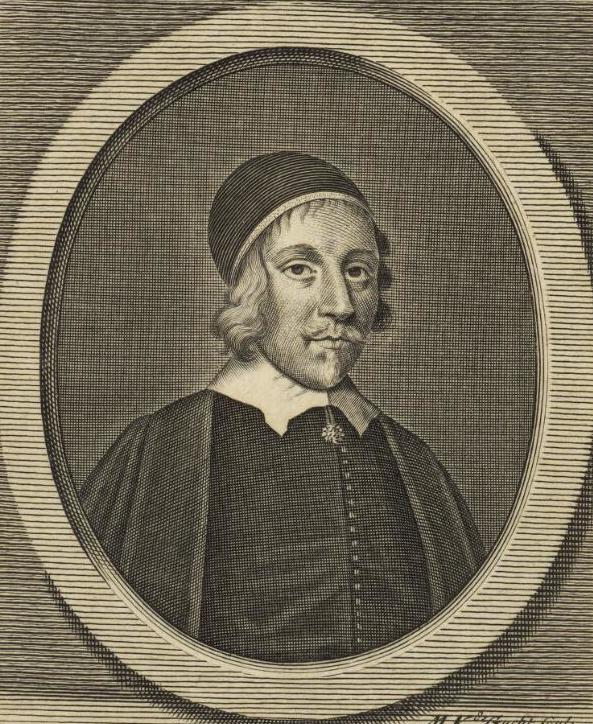

Christopher Love (1618, Cardiff, Wales – 22 August 1651, London) was a

Christopher Love (1618, Cardiff, Wales – 22 August 1651, London) was a

Christopher Love (1618, Cardiff, Wales – 22 August 1651, London) was a

Christopher Love (1618, Cardiff, Wales – 22 August 1651, London) was a Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

preacher and activist during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. In 1651, he was executed by the English government for plotting with the exiled Stuart court. The Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

faction in England considered Love to be a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

and hero.

Life

Love was born in 1618 in Cardiff. At age 14, Love became an adherent to the Puritan congregation. His father disapproved of Love's interests in religion and sent him to London to become an apprentice. However, in 1636, Love's mother and his religious mentor sent him toOxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

instead. When William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury, introduced his Canons of 1640 to reform the English church, Love was one of the first Puritans to renounce them. As a young man, Love became the domestic chaplain to John Warner, the sheriff of London

Two sheriffs are elected annually for the City of London by the Liverymen of the City livery companies. Today's sheriffs have only nominal duties, but the historical officeholders had important judicial responsibilities. They have attended the ju ...

.

St. Ann's, Aldersgate invited Love to become a lecturer, but William Juxon

William Juxon (1582 – 4 June 1663) was an English churchman, Bishop of London from 1633 to 1646 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1660 until his death.

Life

Education

Juxon was the son of Richard Juxon and was born probably in Chichester, ...

, the bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, refused to provide Love with an allowance for three years; Archbishop Laud had warned Juxon to keep an eye on Love. Declining Episcopal ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

, Love went to Scotland to seek ordination from the Presbytery there; However, the Scottish Church would only ordain residents of Scotland and Love planned to return to England.

On Love's return to England around 1641, he was invited by the mayor and aldermen of Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

to preach there. In Newcastle, Love started attacking what he saw as errors in the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'' in his sermons, resulting in his being sent to gaol. After filing a writ of Habeas Corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

, the Newcastle authorities sent Love to London. He was tried in the King's Bench and acquitted of all charges.

Around the outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

, Love preached as a lecturer at Tenterden

Tenterden is a town in the borough of Ashford in Kent, England. It stands on the edge of the remnant forest the Weald, overlooking the valley of the River Rother. It was a member of the Cinque Ports Confederation. Its riverside today is not ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, on the lawfulness of a defensive war. The authorities accused him of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, but Love was again acquitted in court and was able to recover his court costs. Shortly afterward, Love was appointed as chaplain to Colonel John Venn

John Venn, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS, Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, FSA (4 August 1834 – 4 April 1923) was an English mathematician, logician and philosopher noted for introducing Venn diagrams, which are used in l ...

's regiment, and became preacher to the garrison of Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

.

On 23 January 1644, at Aldermanbury, London, Love received Presbyterian ordination from Thomas Horton. Love was one of the first preachers in England to receive this appointment. He then became the pastor of St Lawrence Jewry

St Lawrence Jewry next Guildhall is a Church of England guild church in the City of London on Gresham Street, next to Guildhall. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, and rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren. It is the ...

. According to William Maxwell Hetherington

William Maxwell Hetherington (4 June 1803 – 23 May 1865) was a Scottish minister, poet and church historian. He entered the university of Edinburgh but before completing his studies for the church he published, in 1829, 'Twelve Dramatic S ...

, Love was a superadded member of the Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

. However, this assertion was questioned by Alexander Ferrier Mitchell

Alexander Ferrier Mitchell (1822 – 1899) was a Scottish ecclesiastical historian and Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1885.

Life

He was born at Brechin on 10 September 1822, son of David Mitchell, convener of local ...

, for lack of evidence and the more careful edition of the minutes of the Westminster Assembly by Chad van Dixhorn shows that Hetherington was in error and Love was not made a member of the Assembly.

On 31 January 1645, Love preached an inflammatory sermon in Uxbridge

Uxbridge () is a suburban town in west London and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Situated west-northwest of Charing Cross, it is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the London Plan. Uxb ...

. This was the same day that the commissioners for the Treaty of Uxbridge

The Treaty of Uxbridge was a significant but abortive negotiation in early 1645 to try to end the First English Civil War.

Background

Parliament drew up 27 articles in November 1644 and presented them to Charles I of England at Oxford. Much inpu ...

arrived there. In his ''Vindication'' manuscript, Love claimed that his preaching there was accidental; however, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

voted to bring Love to London and confine him at the House during the negotiations. On 25 November 164, Love preached before the Commons; he did not receive the customary vote of thanks. His House sermon offended the Independents, who on gaining power in the House confined Love again. A House committee for plundered ministers cited Love on two more occasions. Although Love was discharged, the English authorities watched his movements.

Plot to restore Charles II

In 1651, Love became involved in a plot to restore Charles II as the king of England. In the plot, the Presbyterians sent ColonelSilius Titus

Silius Titus (1623–1704), of Bushey, was an English politician, Captain of Deal Castle, and Groom of the Bedchamber to King Charles II. Colonel Titus was an organiser in the attempted escape of King Charles I from Carisbrooke Castle.

Early l ...

to France to deliver letters to Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She was ...

, the mother of Charles II; Colonel Ashworth brought the replies to Love's house in London. On 18 December 1650, Love's wife obtained an official pass to travel to Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

. During this period, Love also received letters from Scottish Presbyterians who were sympathetic to Charles II. Love also hosted discussions in his home how to raise money for firearms from the English Presbyterians.

On 7 May 1651, Love and other prominent Presbyterians were arrested and confined in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

.

On 14 May 1651, Love was ordered to be arrested on charges of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and was confined to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

. In late June and 5 July, he was tried before the high court of justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Senior Courts of England and Wales. Its name is abbreviated as EWHC (Englan ...

. Love was defended by Matthew Hale; presiding at the trial was Richard Keble

Richard Keble (died 1683/84) was an English lawyer and judge, a supporter of the Parliamentarian cause during the English Civil War. During the early years of the Interregnum he was a Keeper of the Great Seal. He was also an active judge who pr ...

.

On 16 July, Love was convicted of treason and sentenced to death. Robert Hammond wrote to Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

asking for leniency for Love. Love received first a one-month reprieve and then a one-week reprieve. On 16 August, Love wrote his final appeal for leniency to the English parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

. In this appeal, he admitted guilt to virtually all of his charges. However, the English courts wanted to make an example of Love to quash any further trouble from the Presbyterians.

Death

On 23 August 1651, Christopher Love was executed onTower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

in London. His execution was attended by Simeon Ashe

Simeon Ashe or Ash (died 1662) was an English nonconformist clergyman, a member of the Westminster Assembly and chaplain to the Parliamentary leader Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester.

Life

He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He b ...

and Edmund Calamy. On 25 August. Love was privately buried at St. Lawrence Church. His funeral sermon was preached by Thomas Manton

Thomas Manton (1620–1677) was an English Puritan clergyman. He was a clerk to the Westminster Assembly and a chaplain to Oliver Cromwell.

Early life

Thomas Manton was baptised 31 March 1620 at Lydeard St Lawrence, Somerset, a remote sou ...

.Bremer-Webster, p. 163. Robert Wild wrote a poem ''The Tragedy of Mr. Christopher Love at Tower Hill'' (1651).

Love was married to Mary Stone, a ward of John Warner. The couple had five children, one of whom was born after Love's death. Three of these children died as babies or small children and only two of their children, Christoper and Mary, lived to be adults. His widow married again to Edward Bradshaw (a twice mayor of Chester) two years after his death and they had six children. Mary died in 1663.

Works

After Love's execution, leading Presbyterians of London (Edmund Calamy, Simeon Ashe, Jeremiah Whitaker, William Taylor, and Allan Geare) published Love's sermons. The most important of his works are: *''Grace, the Truth and Growth, and different Degrees thereof'' (226 pp., London, 1652); *''Heaven's Glory, Hell's Terror'' (350 pp., 1653); *''Combate between the Flesh and the Spirit'' (292 pp., 1654); *''Treatise of Effectual Calling'' (218 pp.,1658); *''The Natural Man's Case Stated'' (8vo, 280 pp., 1658); *''Select Works'' (8vo, Glasgow, 1806–07, 2 vols.). ''Short and plaine Animadversions on some Passages in Mr. Dels' Sermon'' (1646) was a reply toWilliam Dell

William Dell (c. 1607–1669) was an English clergyman, Master of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge from 1649 to 1660, and prominent radical Parliamentarian.

Biography

Dell was born at Bedfordshire, England, and was an undergraduate at Emma ...

. ''A modest and clear Vindication of the ... ministers of London from the scandalous aspersions of John Price'' (1649) (attributed to Love) replied to the ''Clerico-classicum'' of John Price.

Notes

References

*Francis J. Bremer, Tom Webster, ''Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia'' (2006) *Don Kistler ''A Spectacle Unto God: The Life and Death of Christopher Love'' Morgan Pennsylvania: Soli Deo Gloria 1994 ;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Love, Christopher 1618 births 1651 deaths 17th-century apocalypticists 17th-century Protestant martyrs 17th-century Presbyterian ministers Alumni of New Inn Hall, Oxford English Presbyterian ministers People acquitted of treason Welsh Presbyterian ministers of the Interregnum (England) Westminster Divines