Christopher Ingold on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Christopher Kelk Ingold (28 October 1893 – 8 December 1970) was a British

Born in London to a silk merchant who died of tuberculosis when Ingold was five years old, Ingold began his scientific studies at Hartley University College at Southampton (now

Born in London to a silk merchant who died of tuberculosis when Ingold was five years old, Ingold began his scientific studies at Hartley University College at Southampton (now

Review of Leffek's book

by

Biography at Michigan State University

an

at University College London. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ingold, Christopher Kelk British chemists Organic chemists Academics of the University of Leeds Academics of University College London Knights Bachelor Recipients of the British Empire Medal Royal Medal winners Fellows of the Royal Society 1893 births 1970 deaths Faraday Lecturers Alumni of the University of Southampton Alumni of Imperial College London Stereochemists People from Edgware

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

based in Leeds and London. His groundbreaking work in the 1920s and 1930s on reaction mechanisms and the electronic structure of organic compounds was responsible for the introduction into mainstream chemistry of concepts such as nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

, electrophile

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carries ...

, inductive and resonance effect

In chemistry, resonance, also called mesomerism, is a way of describing bonding in certain molecules or polyatomic ions by the combination of several contributing structures (or ''forms'', also variously known as ''resonance structures'' or '' ...

s, and such descriptors as SN1, SN2, E1, and E2. He also was a co-author of the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules

In organic chemistry, the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) sequence rules (also the CIP priority convention; named for R.S. Cahn, C.K. Ingold, and Vladimir Prelog) are a standard process to completely and unequivocally name a stereoisomer of a ...

. Ingold is regarded as one of the chief pioneers of physical organic chemistry

Physical organic chemistry, a term coined by Louis Hammett in 1940, refers to a discipline of organic chemistry that focuses on the relationship between chemical structures and reactivity, in particular, applying experimental tools of physical ch ...

.

Early life and education

Born in London to a silk merchant who died of tuberculosis when Ingold was five years old, Ingold began his scientific studies at Hartley University College at Southampton (now

Born in London to a silk merchant who died of tuberculosis when Ingold was five years old, Ingold began his scientific studies at Hartley University College at Southampton (now Southampton University

, mottoeng = The Heights Yield to Endeavour

, type = Public research university

, established = 1862 – Hartley Institution1902 – Hartley University College1913 – Southampton University Coll ...

) taking an external BSc

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University ...

in 1913 with the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

. He then joined the laboratory of Jocelyn Field Thorpe

Sir Jocelyn Field Thorpe FRS (1 December 1872 – 10 June 1940) was a British chemist who made major contributions to organic chemistry, including the Thorpe-Ingold effect and three named reactions.

Early life and education

Thorpe was b ...

at Imperial College, London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, with a brief hiatus from 1918-1920 during which he conducted research into chemical warfare

Chemical warfare (CW) involves using the toxic properties of chemical substances as weapons. This type of warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare, biological warfare and radiological warfare, which together make up CBRN, the military acronym ...

and the manufacture of poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perman ...

with Cassel Chemical at Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. Ingold received an MSc from the University of London and returned to Imperial College in 1920 to work with Thorpe. He was awarded a PhD in 1918 and a DSc DSC may refer to:

Academia

* Doctor of Science (D.Sc.)

* District Selection Committee, an entrance exam in India

* Doctor of Surgical Chiropody, superseded in the 1960s by Doctor of Podiatric Medicine

Educational institutions

* Dalton State Col ...

in 1921.

Academic career

In 1924 Ingold moved to theUniversity of Leeds

, mottoeng = And knowledge will be increased

, established = 1831 – Leeds School of Medicine1874 – Yorkshire College of Science1884 - Yorkshire College1887 – affiliated to the federal Victoria University1904 – University of Leeds

, ...

where he spent six years as Professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who pr ...

of Organic Chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J.; ...

. He returned to London in 1930, and served for 24 years as head of the chemistry department at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, from 1937 until his retirement in 1961.

During his study of alkyl halide

The haloalkanes (also known as halogenoalkanes or alkyl halides) are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely ...

s, Ingold found evidence for two possible reaction mechanisms for nucleophilic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile). The ...

reactions. He found that tertiary alkyl halides underwent a two-step mechanism (SN1) while primary and secondary alkyl halides underwent a one-step mechanism (SN2). This conclusion was based on the finding that reactions of tertiary alkyl halides with nucleophiles were dependent on the concentration of the alkyl halide only. Meanwhile, he discovered that primary and secondary alkyl halides, when reacting with nucleophiles, depend on both the concentration of the alkyl halide and the concentration of the nucleophile.

Starting around 1926, Ingold and Robert Robinson carried out a heated debate on the electronic theoretical approaches to organic reaction mechanisms. See, for example, the summary by Saltzman.

Ingold authored and co-authored 443 papers.

Honours

In 1920, Ingold was awarded theBritish Empire Medal

The British Empire Medal (BEM; formerly British Empire Medal for Meritorious Service) is a British and Commonwealth award for meritorious civil or military service worthy of recognition by the Crown. The current honour was created in 1922 to ...

(BEM) for his wartime research involving "great courage in carrying out work in a poisonous atmosphere, and risking his life on several occasions in preventing serious accidents," though he subsequently never discussed the award or this period in his life.

Ingold was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

(FRS) in 1924. He received the Longstaff Medal of the Royal Society of Chemistry

The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) is a learned society (professional association) in the United Kingdom with the goal of "advancing the chemistry, chemical sciences". It was formed in 1980 from the amalgamation of the Chemical Society, the Ro ...

in 1951, the Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1952, and was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

in 1958.

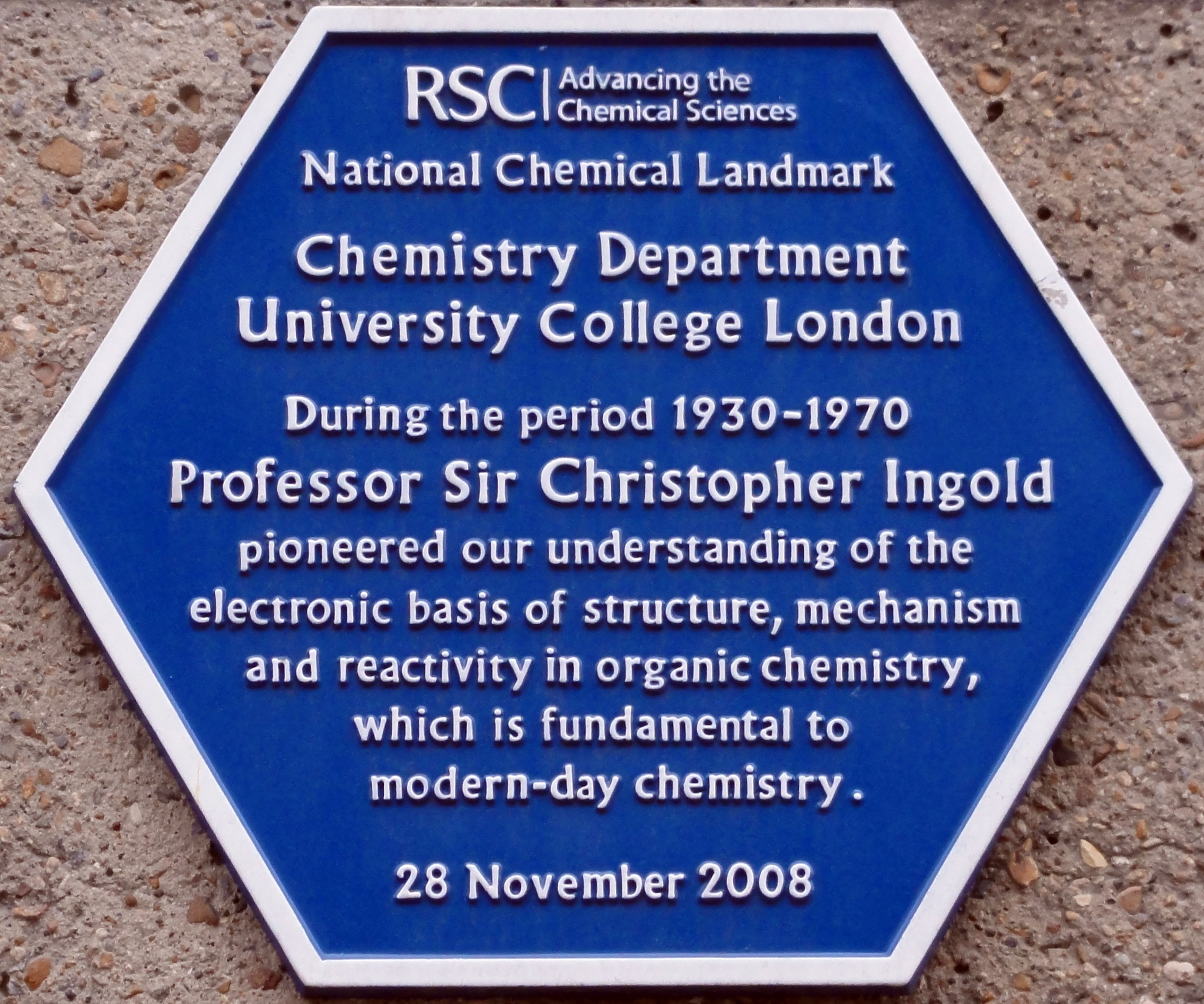

The chemistry department of University College London is now housed in the Sir Christopher Ingold building, opened in 1969.

Personal life

Ingold married Dr. Hilda Usherwood in 1923. She was a fellow chemist with whom he collaborated. They had two daughters and a son, the chemistKeith Ingold

Keith Usherwood Ingold, (born 31 May 1929) is a British chemist.

He was born to Sir Christopher Ingold and Dr. Hilda Usherwood, and studied for a BSc in Chemistry at the University of London, completing his degree in 1949. He continued his h ...

.

Death

Ingold died in London in 1970, aged 77.References

Further reading

Dr. Malmberg's class: K.P. *Review of Leffek's book

by

John D. Roberts

John Dombrowski Roberts (June 8, 1918 – October 29, 2016) was an American chemist. He made contributions to the integration of physical chemistry, spectroscopy, and organic chemistry for the understanding of chemical reaction rates. Ano ...

*

External links

Biography at Michigan State University

an

at University College London. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ingold, Christopher Kelk British chemists Organic chemists Academics of the University of Leeds Academics of University College London Knights Bachelor Recipients of the British Empire Medal Royal Medal winners Fellows of the Royal Society 1893 births 1970 deaths Faraday Lecturers Alumni of the University of Southampton Alumni of Imperial College London Stereochemists People from Edgware