Christianization (

or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, continued through the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

in Europe, and in the twenty-first century has spread around the globe. Historically, there are four stages of Christianization beginning with individual conversion, followed by the translation of Christian texts into local vernacular language, establishing education and building schools, and finally, social reform that sometimes emerged naturally and sometimes included politics, government, coercion and even force through

colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

.

The first countries to make Christianity their state religion were Armenia, Georgia, Ethiopia and Eritrea. In the fourth to fifth centuries, multiple tribes of Germanic barbarians converted to either Arian or orthodox Christianity. The Frankish empire begins during this same period. Missionaries were sent to Ireland and Great Britain leading to peaceful conversions in both countries. Italy produced the most influential monastic movement of the Middle Ages through Benedict of Nursia, while Greece lagged behind the rest of the Roman empire in conversion. Under the Eastern Emperor

Justinian the first, Ancient Christianity begins its end, transforming into its eclectic medieval forms.

Medieval Christianization began in Europe in the 8th and 9th centuries. A new region of Europe that later became known as Eastern Central Europe is formed, though not completely without bloodshed, since throughout central and eastern Europe, Christianization and political centralization went hand in hand. The rulers of

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

,

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

(which became

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

), the

Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

and the

Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, along with

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

, and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, voluntarily joined the Western, Latin church, sometimes pressuring their people to follow. The Christianization of the Kievan Rus, the ancestors of

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, and

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, began in the tenth century following the path of Byzantine Christianity and becoming a true state church with state control of religion and some coercion.

The two centuries around the turn of the first millennium brought Europe's most significant Christianization of the early Middle Ages.

What had been, for Europe, two dangerous and aggressive enemies, (the Scandinavian Vikings (Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes) on the northern borders and the Hungarians on the eastern border), voluntarily adopted Christianity and founded kingdoms that sought a place among the European states.

Whereas, the Northern Crusades from 1147 to 1316 form a unique chapter in Christianization. They were not for the recuperation of previously lost Christian territory, nor were they organized against invasive Muslims; instead, they were largely political, led by local princes against their own enemies and for their own gain, and conversion by these princes was almost always a result of armed conquest.

Christianization

Christianization occurs when an individual, a practice, a place, or a society becomes identified as Christian in some capacity or other, such as a change in identity, values, goals or use. In sociology, Christianization of a city is seen as the emergence of the first Christian congregation in that city. There are four stages in the historically observed process. The first stage most often began with the conversion of individuals, then moved to translation of the Bible into the local language, often inventing the written script, and thereby spreading literacy and education, and various public ministries which then often led to subsequent cultural changes.

Lamin Sanneh

Lamin Sanneh (May 24, 1942 – January 6, 2019) was the D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School and Professor of History at Yale University.

Biography

Sanneh was born and raised in Gambia as part of ...

writes that tracing the impact on local cultures shows Christianization has often produced "the movements of

indigenization

Indigenization is the act of making something more native; transformation of some service, idea, etc. to suit a local culture, especially through the use of more indigenous people in public administration, employment and other fields.

The term i ...

and cultural liberation".

Some societies became Christianized through

evangelization

In Christianity, evangelism (or witnessing) is the act of preaching the gospel with the intention of sharing the message and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Christians who specialize in evangelism are often known as evangelists, whether they are ...

by monks or priests, or by organic growth within an already partly Christianized society. Some societies were Christianized by campaigns that included converting native practices and culture and transforming pagan sites to Christian uses. Ancient barbarian societies tended to be communal by nature rather than oriented around individuality, and loyalty to the king meant the conversion of the ruler was generally voluntarily followed by the mass conversion of his subjects. In the

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

the mixture of religion with politics and the personal ambitions of individual leaders led to some instances of forced conversion by the sword. There is history connecting

Christianization and colonialism, especially but not limited to the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

and other regions subject to

settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a structure that perpetuates the elimination of Indigenous people and cultures to replace them with a settler society. Some, but not all, scholars argue that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal. It may be enacted ...

.

Christianization has never been a one-way process. There has been, instead, a parallelism in Christianization as it absorbed indigenous elements just as indigenous religions absorbed aspects of Christianity. According to archaeologist Anna Collar, when groups of people with different ways of life come into contact with each other and exchange ideas and practices, this

trans-cultural diffusion

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, te ...

causes societies to evolve, progress and change. This exchange has at times involved appropriation and redesignation of aspects of native religion that survived to find a place in the new religious system. In some cases these survivals were encouraged by Christian missionaries, while other aspects of traditional religion survived despite the opposition of the missionaries.

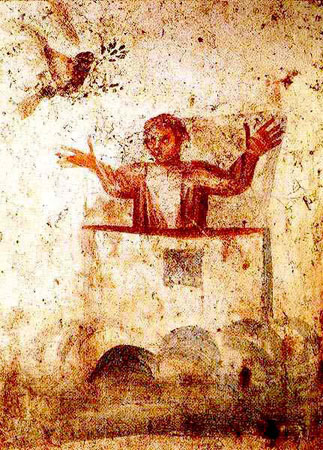

Ancient (Ante-Nicaean) Christianity (1st to 3rd centuries)

Christianization began in the Roman Empire in Jerusalem around 30–40 AD, spreading outward quickly. The Church in Rome was founded by

Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

and

Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

in the 1st century. There is agreement among twenty-first century scholars that Christianization of the Roman Empire in its first three centuries did not happen by imposition. Christianization of this period was the cumulative result of multiple individual decisions and behaviors. Recent research has shown it was the formal unconditional altruism of early Christianity that accounts for much of its otherwise surprising degree of early success. Aspects of its ideology, and its social actions, such as charity, care for the sick and acceptance of those who were otherwise rejected for their lack of Roman status, made Christianity attractive to Romans who had nothing comparable in Roman society.

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories. Many scholars have seen this inclusivity as the primary reason for Christianization's early success. The

Council of Jerusalem

The Council of Jerusalem or Apostolic Council was held in Jerusalem around AD 50. It is unique among the ancient pre-ecumenical councils in that it is considered by Catholics and Eastern Orthodox to be a prototype and forerunner of the later ...

(around 50 AD) agreed the lack of

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Top ...

could not be a basis for excluding

Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

believers from membership in the Jesus community. They instructed converts to avoid "pollution of idols, fornication, things strangled, and blood" (

KJV

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

, Acts 15:20–21). These were put into writing, distributed (

KJV

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

Acts 16:4–5) by messengers present at the council, and were received as an encouragement. The

Apostolic Decree helped to establish Ancient Christianity as unhindered by either ethnic or geographical ties. Christianity was experienced as a new start, and was open to both men and women, rich and poor. Baptism was free. There were no fees, and it was intellectually

egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, making

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

and

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concer ...

available to ordinary people including those who might have lacked

literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in Writing, written form in some specific context of use. In other wo ...

.

Heterogeneity

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

characterized the groups formed by

Paul the Apostle

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, and the role of

women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

was much greater than in any of the forms of Judaism or paganism in existence at the time.

Ante-Nicaean Christianity was also highly exclusive. Believing was the crucial and defining characteristic that set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded the "

unbeliever

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Churc ...

".

Keith Hopkins asserts: "It is this exclusivism, idealized or practiced, which marks Christianity off from most other religious groups in the ancient world". In the ''

Epistle to Diognetus

The ''Epistle of Mathetes to Diognetus'' ( el , Πρὸς Διόγνητον Ἐπιστολή) is an example of Christian apologetics, writings defending Christianity against the charges of its critics. The Greek writer and recipient are not ot ...

'', an extant late second century letter to a Roman official, the anonymous author observes that early Christians functioned as if they were a separate "third race": a nation within a nation. The Christian apologist Tertullian in his ''ad nationes'' (1.8; cf. 1.20), mocked the accusation that ‘we are called a third race’, yet there is also ambivalence, since he takes some pride in the uniqueness it represents. The early Christian had exacting moral standards that included avoiding contact with those that were seen as still "in bondage to the Evil One": (

2 Corinthians 6:1-18;

1 John 2: 15-18;

Revelation 18: 4; II Clement 6; Epistle of Barnabas, 1920). In Daniel Praet's view, the exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success, enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that

syncretized

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, th ...

religion.

While enduring three centuries of on again - off again persecution, from differing levels of government ranging from local to imperial, Christianity had remained 'self-organized' and without central authority. In this manner, it reached an important

threshold of success between 150 and 250, when it moved from less than 50,000 adherents to over a million, and became self-sustaining and able to generate enough further growth that there was no longer a viable means of stopping it. Scholars agree there was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the third century.

Christian monasticism

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural ex ...

emerged in the third century, and

monks

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

soon became crucial to the process of Christianization. Their numbers grew such that, "by the fifth century, monasticism had become a dominant force impacting all areas of society".

Armenia, Georgia, Ethiopia and Eritrea

In 301,

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

became the first kingdom in history to adopt Christianity as an official state religion. The transformations taking place in these centuries of the Roman Empire had been slower to catch on in Caucasia. Indigenous writing did not begin until the fifth century, there was an absence of large cities, and many institutions such as monasticism did not exist in Caucasia until the seventh century. Scholarly consensus places the Christianization of the Armenian and Georgian elites in the first half of the fourth century, although Armenian tradition says Christianization began in the first century through the Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew. This is said to have eventually led to the conversion of the Arsacid family, (the royal house of Armenia), through

St. Gregory the Illuminator

Gregory the Illuminator ( Classical hy, Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ, reformed: Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ, ''Grigor Lusavorich'';, ''Gregorios Phoster'' or , ''Gregorios Photistes''; la, Gregorius Armeniae Illuminator, cu, Svyas ...

in the early fourth century. Christianization took many generations and was not a uniform process. Robert Thomson writes that it was not the officially established hierarchy of the church that spread Christianity in Armenia. "It was the unorganized activity of wandering holy men that brought about the Christianization of the populace at large". The most significant stage in this process was the development of a script for the native tongue.

Scholars do not agree on the exact date of

Christianization of Georgia

The Christianization of Iberia ( ka, ქართლის გაქრისტიანება, tr) refers to the spread of Christianity in the early 4th century by the sermon of Saint Nino in an ancient Georgian kingdom of Kartli, known a ...

, but most assert the early 4th century when

Mirian III

Mirian III ( ka, მირიან III) was a king of Iberia or Kartli (Georgia), contemporaneous to the Roman emperor Constantine the Great ( r. 306–337). He was the founder of the royal Chosroid dynasty.

According to the early medieval Geo ...

of the

Kingdom of Iberia

In Greco-Roman geography, Iberia (Ancient Greek: ''Iberia''; la, Hiberia) was an exonym for the Georgian kingdom of Kartli ( ka, ქართლი), known after its core province, which during Classical Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages ...

(known locally as

Kartli

Kartli ( ka, ქართლი ) is a historical region in central-to-eastern Georgia traversed by the river Mtkvari (Kura), on which Georgia's capital, Tbilisi, is situated. Known to the Classical authors as Iberia, Kartli played a crucial rol ...

) adopted Christianity. According to medieval

Georgian Chronicles

''The Georgian Chronicles'' is a conventional English name for the principal compendium of medieval Georgian historical texts, natively known as ''Kartlis Tskhovreba'' ( ka, ქართლის ცხოვრება), literally "Life of Ka ...

, Christianization began with

Andrew the Apostle

Andrew the Apostle ( grc-koi, Ἀνδρέᾱς, Andréās ; la, Andrēās ; , syc, ܐܰܢܕ݁ܪܶܐܘܳܣ, ʾAnd’reʾwās), also called Saint Andrew, was an apostle of Jesus according to the New Testament. He is the brother of Simon Pete ...

and culminated in the evangelization of Iberia through the efforts of a captive woman known in Iberian tradition as

Saint Nino

Saint Nino ( ka, წმინდა ნინო, tr; hy, Սուրբ Նունե, Surb Nune; el, Αγία Νίνα, Agía Nína; sometimes ''St. Nune'' or ''St. Ninny'') ''Equal to the Apostles and the Enlightener of Georgia'' (c. 296 – c. 33 ...

in the fourth century. Fifth, 8th, and 12th century accounts of the conversion of Georgia reveal how pre-Christian practices were taken up and reinterpreted by Christian narrators.

In 325, the

Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in w ...

(Modern Ethiopia and Eritrea) became the second country to declare Christianity as its official state religion.

Late antiquity (4th–5th centuries)

Favoritism and hostility

The Christianization of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

is frequently divided by scholars into the two phases of before and after the conversion of

Constantine in 312. Constantine has long been credited with ending the

persecution of Christianity

The persecution of Christians can be historically traced from the first century of the Christian era to the present day. Christian missionaries and converts to Christianity have both been targeted for persecution, sometimes to the point of ...

and establishing religious tolerance with the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, but the nature of the Edict, and Constantine's faith, are both heavily debated in the twenty-first century. According to

Harold A. Drake

Harold A. Drake (born 1942) is an American scholar of Ancient Roman history, with an emphasis on late antiquity.

Born in 1942, Drake grew up in Southern California and attended North Hollywood High School. He discussed the possibility of a career ...

, Constantine's official imperial religious policies did not stem from faith as much as they stemmed from his duty as Emperor to maintain peace in the empire. Drake asserts that, since Constantine's reign followed Diocletian's failure to enforce a particular religious view, Constantine was able to observe that coercion had not produced peace.

Contemporary scholars are in general agreement that Constantine did not support the suppression of paganism by force. He never engaged in a

purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

, there were no pagan martyrs during his reign. Pagans remained in important positions at his court. Constantine ruled for 31 years and never outlawed paganism. A few authors suggest that "true Christian sentiment" might have motivated Constantine, since he held the conviction that, in the realm of faith, only freedom mattered.

During his long reign, Constantine destroyed a few temples, plundered more, and generally neglected the rest; he "confiscated temple funds to help finance his own building projects", and he confiscated temple hoards of gold and silver to establish a stable currency; on a few occasions, he confiscated temple land; he refused to personally support pagan beliefs and practices while also speaking out against them; yet Constantine did not stop the established state support of the traditional religious institutions. He forbade pagan sacrifices and closed temples that continued to offer them;

[Peter Brown, ''Rise of Christendom'' 2nd edition (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2003) p. 74.] he wrote laws that favored Christianity; he granted to Christians those governmental privileges, such as tax exemptions and the right to hold property, that had previously been available only to pagan priests; he personally endowed Christians with gifts of money, land and government positions.

[MacMullen, R. ''Christianizing The Roman Empire A.D.100-400'', Yale University Press, 1984, ]

Making the adoption of Christianity beneficial was Constantine's primary approach to religion, and imperial favor was important to successful Christianization over the next century. However, Constantine must have written the laws that threatened and menaced pagans who continued to practice sacrifice. There is no evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted. There is no record of anyone being executed for violating religious laws before Tiberius II Constantine at the end of the sixth century (574–582). Still, classicist Scott Bradbury notes that the complete disappearance of public sacrifice by the mid-fourth century "in many towns and cities must be attributed to the atmosphere created by imperial and episcopal hostility".

Paganism did not end just because public sacrifice did. Constantius II created a series of anti-pagan laws in 353 and 354, and had the altar of victory removed, but while this stirred up fear and resentment, it did not end paganism. Brown explains that polytheists were accustomed to offering prayers to the gods in many ways and places that did not include sacrifice, that pollution was only associated with sacrifice, and that the ban on sacrifice had fixed boundaries and limits. Paganism thus remained widespread into the early fifth century continuing in parts of the empire into the seventh.

[Salzman, M.R., ''The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire'' (2002), p. 182] Historian John Curran writes that, under Constantine's successors, Christianization of Roman society proceeded by fits and starts.

Rewriting history

Late Antiquity from the third to the sixth centuries was the era of the development of the great Christian narrative, an ''interpretatio Christiana'' of the history of humankind. This meant reassessing and relocating past histories, ideas and persons on the historical mental map. In this construction of the past, Christian writers built on the models of the preceding tradition, creating competing chronologies and alternative histories.

In the early fourth century, Eusebius wrote ''Chronici canones''. In it, he developed an elaborate synchronistic chronology wherein he reinterpreted the Greco-Roman past to reflect a Christian perspective. In the early fifth century Orosius wrote ''Historiae adversus paganos'' in response to the charge that the Roman Empire was in misery and ruins because it had converted to Christianity and neglected the old gods.

Maijastina Kahlos explains that, "In order to refute these claims, Orosius reviewed the entire history of Rome, demonstrating that the alleged glorious past of the Romans in fact consisted of war, despair and suffering. Orosius’s ''Historiae adversus paganos'' is a counter-narrative... Instead of a magnificent Roman past, he construes a history in which ... Christ is born and Christianity appears to have appeared ... just when Roman power was at its height – all this according to a divine plan... Both writers took over and reinterpreted the Greco-Roman past to explain and legitimize their own present".

Christian literature of the fourth century does not focus on converting and Christianizing pagans. Instead, it is filled with the triumph of Constantine's conversion as evidence of the Christian god's final triumph in Heaven over the pagan gods. Historian

Peter Brown indicates that, as a result of this "triumphalism," paganism was seen as vanquished despite the ongoing presence of a pagan majority,

Theodosius I and orthodoxy

In the centuries following his death, Theodosius I gained a reputation as the emperor who established Christianity as the one official religion of the empire. Modern historians see this as a later interpretation of history – a rewriting of history by Christian writers beginning with the bishop

Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promot ...

– rather than actual history.

Theodosius championed Christian orthodoxy, making repeated efforts through law to eliminate heresies and promote unity within Christianity. In 380, he issued the

Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds such as Arianism ...

to the people of Constantinople. It was valid throughout the East. It was addressed to Christians, since only Christians can be heretics. More specifically, it threatens Arian Christians, but it granted Christians no favors or advantages over other religions, and it is clear from mandates issued in the years after 380, that Theodosius had not intended it as a requirement for pagans or Jews to convert to Christianity. Hungarian legal scholar Pál Sáry explains that, "In 393, the emperor was gravely disturbed that the Jewish assemblies had been forbidden in certain places. For this reason, he stated with emphasis that the sect of the Jews was forbidden by no law".

Scholars say there is little, if any, evidence that Theodosius I pursued an active policy against the traditional cults. As his predecessors had, he too outlawed all forms of sacrifice, public and private, and the magic associated with sacrifice, and called for the closure of temples that illegally continued to offer sacrifices. Some scholars have said that a universal ban on paganism and the establishment of Christianity as the singular religion of the empire can be implied from some of Theodosius' laws. During the reign of Theodosius, pagans were continuously appointed to prominent positions and pagan aristocrats remained in high offices.

In his 2020 biography of Theodosius, Mark Hebblewhite concludes that Theodosius never saw himself, or advertised himself, as a destroyer of the old cults. The emperor's efforts at Christianization were "targeted, tactical, and nuanced".

Force

There is no evidence to indicate that conversion of pagans through force was an accepted method of Christianization at any point in Late Antiquity; all uses of imperial force concerning religion were aimed at Christian heretics such as the

Donatists

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and t ...

and the

Manichaeans

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (AD ...

. Augustine, who advocated coercion for heretics, did not do so for the pagans or the Jews of his era, and the distinction between heretical Christians and non-believers continued to be made up to and through

Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

in the thirteenth century.

According to H. A. Drake, Christians worried about the validity of coerced faith and resisted such aggressive actions for centuries. In Peter Garnsey's view, "Christians were the only group in antiquity to enunciate conditions for practicing religious toleration as a principle, rather than as an expedient". Tertullian held that 'the free exercise of religious choice was a tenet of both man made and natural law', and that religion was 'something to be taken up voluntarily, not under duress". In the fourth century, a council of Spanish Bishops meeting in

Elvira

Elvira is a female given name. First recorded in medieval Spain, it is likely of Germanic (Gothic) origin.

Elvira may refer to:

People Nobility

* Elvira Menéndez (died 921), daughter of Hermenegildo Gutiérrez and wife of Ordoño II of Leó ...

on the coast of Spain, determined that Christians who died in attacks on idol temples should not be received as martyrs. The bishops wrote that they took this stand of disapproval because "such actions cannot be found in the Gospels, nor were they ever undertaken by the Apostles". Drake suggests this stands as testimony to the tradition established in early Christianity which favored and operated toward peace, moderation, and conciliation. It was a tradition that held true belief could not be compelled for the simple reason that God could tell the difference between voluntary and coerced worship. In Peter Brown's view of the late fourth century,

It would be a full two centuries before Justinian would envisage the compulsory baptism of remaining polytheists, and a further century until Heraclius and the Visigothic kings of Spain would attempt to baptize the Jews. In the fourth century, such ambitious schemes were impossible.

Before the fifth century, there were isolated local incidents of anti-Jewish violence, and there were legislative pressures against specific pagan practices, but according to historians of forced conversion Mercedes García-Arenal and Yonatan Glazer-Eytan, it is only with the legislation introduced during the seventh century Visigothic period that a different view of the use of coercion or force began to develop in Spain.

Germanic conversions

The earliest references to the Christianization of the Germanic peoples are in the writings of

Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

(130–202 ),

Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

(185-253), and

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

(''Adv. Jud. VII'') (155–220).

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian ...

and

Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

omit Germany from their lists of Christianized peoples, but that is possibly because, by the 4th century, many from the Eastern Germanic tribes, notably the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

, had adopted

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

. Noel Lenski writes that the emperor Valens offered encouragement rather than active sponsorship of Christianization beyond Roman borders.

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

is an important early source describing the nature of German religion, and their understanding of the function of a king, as facilitating Christianization. Conversion of the West and East Germanic tribes sometimes took place "top to bottom" in the sense that missionaries aimed at converting Germanic nobility first. A king had divine lineage as a descendent of

Woden

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

. Ties of fealty between German kings and their followers often rested on the agreement of loyalty for reward; the concerns of these early societies were communal, not individual; this combination produced mass conversions of entire tribes following their king, trusting him to share the rewards of conversion with them accordingly. Afterwards, their societies began a gradual process of Christianization that took centuries, with some traces of earlier beliefs remaining.

* In 341, Romanian born Ulfila (''Wulfilas'', 311–383) became a bishop and was sent to instruct the Gothic Christians living in Gothia in the province of

Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

. Ulfilas is traditionally credited with the voluntary conversion of the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

between 369 and 372.

* The

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

converted to Arian Christianity shortly before they left Spain for northern Africa in 429.

*

Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

converted to Catholicism sometime around 498, extending his kingdom into most of Gaul (France) and large parts of what is now modern Germany.

* The

Ostrogothic kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic peoples, Germanic Ostrogoths in Italian peninsula, Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the ...

, which included all of Italy and parts of the Balkans, began in 493 with the killing of

Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus Augustul ...

by

Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

. They converted to Arianism.

* Christianization of the central

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

is documented at the end of the 4th century, where

Nicetas

Nicetas or Niketas () is a Greek given name, meaning "victorious one" (from Nike "victory").

The veneration of martyr saint Nicetas the Goth in the medieval period gave rise to the Slavic forms: ''Nikita, Mykyta and Mikita''

People with the name N ...

the Bishop of

Remesiana

Remesiana (Byzantine Greek: Ρεμεσιανισία) was an ancient Roman city and former bishopric, which remains an Eastern Orthodox and also a Latin Catholic titular see, located around and under the modern city of Bela Palanka in Serbia.

R ...

brought the gospel to "those mountain wolves", the

Bessi.

* The

Langobardic

Lombardic or Langobardic is an extinct West Germanic language that was spoken by the Lombards (), the Germanic people who settled in Italy in the sixth century. It was already declining by the seventh century because the invaders quickly adopted ...

kingdom, which covered most of Italy, began in 568, becoming Arian shortly after the conversion of

Agilulf

Agilulf ( 555 – April 616), called ''the Thuringian'' and nicknamed ''Ago'', was a duke of Turin and king of the Lombards from 591 until his death.

A relative of his predecessor Authari, Agilulf was of Thuringian origin and belonged to the An ...

in 607. Most scholars assert that the Lombards, who had lived in

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

and along the

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

river, converted to Christianity when they moved to Italy in 568, since it was thought they had little to do with the empire before then. According to the Greek scholar

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

(500-565), the Lombards had "occupied a Roman province for 40 years before moving into Italy". It is now thought that the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

first adopted Christianity while still in Pannonia. Procopius writes that, by the time the Lombards moved into Italy, "they appear to have had some familiarity already with both Christianity and some elements of Roman administrative culture".

In all these cases, "the Germanic conquerors lost their native languages. In the remaining parts of the Germanic world, that is, to the North and East of France, the Germanic languages were maintained, but the syntax, the conceptual framework underlying the lexicon, and most of the literary forms were thoroughly latinized".

St. Boniface led the effort in the mid-eighth century to organize churches in the region that would become modern Germany.

As ecclesiastical organization increased, so did the political unity of the Germanic Christians. By the year 962, when

Pope John XII

Pope John XII ( la, Ioannes XII; c. 930/93714 May 964), born Octavian, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 16 December 955 to his death in 964. He was related to the counts of Tusculum, a powerful Roman family which had do ...

anoints

King Otto I as Holy Roman Emperor, "Germany and Christendom become one".

This union lasted until dissolved by Napoleon in 1806.

Ireland

Pope Celestine I

Pope Celestine I ( la, Caelestinus I) (c. 376 – 1 August 432) was the bishop of Rome from 10 September 422 to his death on 1 August 432. Celestine's tenure was largely spent combatting various ideologies deemed heretical. He supported the missi ...

(422-430) sent

Palladius to be the first bishop to the Irish in 431, and in 432,

St Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

began his mission there. Scholars cite many questions (and scarce sources) concerning the next two hundred years. Relying largely on recent archaeological developments, Lorcan Harney has reported to the Royal Academy that the missionaries and traders who came to Ireland in the fifth to sixth centuries were not backed by any military force. Conversion and consolidation were long complex processes that took centuries.

Patrick and Palladius and other British and Gaulish missionaries aimed first at converting royal households. Patrick indicates in his ''Confessio'' that safety depended upon it. Communities often followed their king en masse. It is likely most natives were willing to embrace the new religion, and that most religious communities were willing to integrate themselves into the surrounding culture.

Christianization of the Irish landscape was a complex process that varied considerably depending on local conditions. Ancient sites were viewed with veneration, and were excluded or included for Christian use based largely on diverse local feeling about their nature, character, ethos and even location.

The Irish monks developed a concept of ''peregrinatio'' where a monk would leave the monastery to preach among the 'heathens'. From 590, Irish missionaries were active in

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, Scotland,

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

and Britain.

Great Britain

The most likely date for Christianity getting its first foothold in Britain is sometime around 200. Recent archaeology indicates that it had become an established minority faith by the fourth century. It was largely mainstream, and in certain areas, had been continuous.

[Thomas, Charles. "Evidence for Christianity in Roman Britain. The Small Finds. By CF Mawer. BAR British Series 243. Tempus Reparatum, Oxford, 1995. Pp. vi+ 178, illus. ISBN 0 8605 4789 2." Britannia 28 (1997): 506-507.]

The conversion of the

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

was begun at about the same time in both the north and south of the

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

The Heptarchy were the seven petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England that flourished from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until they were consolidated in the 8th century into the four kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria, Wes ...

in two unconnected initiatives. Irish missionaries led by Saint

Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

, based in

Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there ...

(from 563), converted many

Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

. The court of Anglo-Saxon

Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

, and the

Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to conver ...

, who landed in 596, did the same to the

Kingdom of Kent

la, Regnum Cantuariorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the Kentish

, common_name = Kent

, era = Heptarchy

, status = vassal

, status_text =

, government_type = Monarchy ...

. They had been sent by

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

and were led by

Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

with a mission team from Italy. In both cases, as in other kingdoms of this period, conversion generally began with the royal family and the nobility adopting the new religion first.

In early Anglo-Saxon England, non-stop religious development meant paganism and Christianity were never completely separate. Lorcan Harney has reported that Anglo-Saxon churches were not built by pagan barrows before the 11th century.

Frankish Empire

The Franks first appear in the historical record in the 3rd century as a confederation of Germanic tribes living on the east bank of the lower Rhine River.

Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

was the first

king of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

to unite all of the

Frankish tribes under one ruler. According to legend, Clovis had prayed to the Christian god before his battle against one of the kings of the

Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

, and had consequently attributed his victory to Jesus.

[Padberg, Lutz v. (1998), p.48] The most likely date of his conversion to Catholicism is Christmas Day, 508, following that

Battle of Tolbiac.

He was baptized in

Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

. The Frankish Kingdom became Christian over the next two centuries.

[Lund, James. "RELIGION AND THOUGHT." Modern Germany (2022): 113.]

The conversion of the northern Saxons began with their forced incorporation into the Frankish kingdom in 776 by

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

(r. 768–814). Thereafter, the Saxon's Christian conversion slowly progressed into the eleventh century.

Saxons had gone back and forth between rebellion and submission to the Franks for decades. Charlemagne placed missionaries and courts across Saxony in hopes of pacifying the region, but Saxons rebelled again in 782 with disastrous losses for the Franks. In response, the Frankish King "enacted a variety of draconian measures" beginning with the

massacre at Verden in 782 when he ordered the decapitation of 4500 Saxon prisoners offering them baptism as an alternative to death. These events were followed by the severe legislation of the ''Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae'' in 785 which prescribes death to those that are disloyal to the king, harm Christian churches or its ministers, or practice pagan burial rites.

[Barbero, Alessandro (2004). ''Charlemagne: Father of a Continent'', page 46. ]University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

. His harsh methods of Christianization raised objections from his friends

Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

and

Paulinus of Aquileia

Saint Paulinus II ( 726 – 11 January 802 or 804 AD) was a priest, theologian, poet, and one of the most eminent scholars of the Carolingian Renaissance. From 787 to his death, he was the Patriarch of Aquileia. He participated in a number of synod ...

. Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797.

Italy

Christianization throughout Italy in Late Antiquity allowed for an amount of religious competition, negotiation, toleration and cooperation; it included syncretism both to and from pagans and Christians; and it allowed for a great deal of secularism. Public sacrifice had largely disappeared by the mid-fourth century, but paganism in a broader sense did not end. Paganism continued, transforming itself over the next two centuries in ways that often included the appropriation and redesignation of Christian practices and ideas while remaining pagan.

In 529,

Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Orient ...

established his first monastery in the Abbey of

Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first h ...

, Italy. He wrote the

Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

based on "pray and work". This "Rule" provided the foundation of the majority of the thousands of monasteries that spread across what is modern day Europe thereby becoming a major factor in the Christianization of Europe. Monasteries were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making, and various other skills.

They were havens for the poor, hospitals, hospices for the dying, and schools. Medical practice was highly important, and monasteries are best known for their contributions to medical tradition. They also made advances in sciences such as astronomy. For centuries, nearly all secular leaders were trained by monks because, excepting private tutors who were still, often, monks, it was the only education available.

The formation of these organized bodies of believers gradually carved out a series of uniquely distinct social spaces with some amount of independence from other types of authority such as political and familial authority. This revolutionized social history for everyone, but especially for women who could become leaders of communities with great influence of their own.

Benedict's biographer Cuthbert Butler writes that "...certainly there will be no demur in recognizing that St. Benedict's Rule has been one of the great facts in the history of western Europe, and that its influence and effects are with us to this day."

Greece

Christianization was slower in Greece than in most other parts of the Roman empire. There are multiple theories of why, but there is no consensus. What is agreed upon is that, for a variety of reasons, Christianization did not take hold in Greece until the fourth and fifth centuries. Christians and pagans maintained a self imposed segregation throughout the period. In Athens, for example, pagans retained the old civic center with its temples and public buildings as their sphere of activity, while Christians restricted themselves to the suburban areas. There was little direct contact between them. J. M. Speiser has argued that this was the situation throughout the country, and that "rarely was there any significant contact, hostile or otherwise" between Christians and pagans in Greece. This would have slowed the process of Christianization. By the time Christianization showed up in Greece, many of the fundamental aspects of the two religious traditions had already become similar. Accommodations had been made in both directions allowing points of view acceptable to those who had previously been pagan.

Timothy Gregory says, "it is admirably clear that organized paganism survived well into the sixth century throughout the empire and in parts of Greece (at least in the

Mani

Mani may refer to:

Geography

* Maní, Casanare, a town and municipality in Casanare Department, Colombia

* Mani, Chad, a town and sub-prefecture in Chad

* Mani, Evros, a village in northeastern Greece

* Mani, Karnataka, a village in Dakshi ...

) until the ninth century or later". Gregory adds that pagan ideas and forms persisted most in practices related to healing, death, and the family. These are "first-order" concerns - those connected with the basics of life – which were not generally subjected to objections from theologians and bishops.

The

Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, the

Erechtheion

The Erechtheion (latinized as Erechtheum /ɪˈrɛkθiəm, ˌɛrɪkˈθiːəm/; Ancient Greek: Ἐρέχθειον, Greek: Ερέχθειο) or Temple of Athena Polias is an ancient Greek Ionic temple-telesterion on the north side of the Acropoli ...

, and the

Theseion were turned into churches, but Alison Frantz has won consensus support of her view that, aside from a few rare instances, temple conversions took place only after Late Antiquity, especially in the seventh century, after the displacements caused by the Slavic invasions.

Sept. 22nd, 529 has been regarded by some scholars as the symbolic marking fthe end of antiquity in the Eastern Roman Empire: the date corresponds to Justinian’s closing of the philosophical school at Athens, a fact whose historicity is beyond doubt, and whose effects on the cultural life of the Greek East have been variously assessed.

Iberian Peninsula

Hispania had become part of the Roman Empire in the third century BC. In his Epistle to the Romans, the Apostle Paul speaks of his intent to travel there, but when, how, and even if this happened, is uncertain. Paul may have begun the Christianization of Spain, but it may have been begun by soldiers returning from Mauritania. However Christianization began, Christian communities can be found dating to the third century, and bishoprics had been created in León, Mérida and Zeragosa by that same period. In AD 300 an ecclesiastical council held in Elvira was attended by 20 bishops. With the end of persecution in 312, churches, baptistries, hospitals and episcopal palaces were erected in most major towns, and many landed aristocracy embraced the faith and converted sections of their villas into chapels.

In 416, the Germanic Visigoths crossed into Hispania as Roman allies. They converted to Arian Christianity shortly before 429. The Visigothic King Sisebut came to the throne in 612 when the Roman emperor Heraclius surrendered his Spanish holdings.

The emperor had received a prophecy that the empire would be destroyed by a circumcised people; lacking awareness of Islam, he applied this to the Jews. Heraclius is said to have called upon Sisebut to banish all Jews who would not submit to baptism. Bouchier says 90,000 Hebrews were baptized while others fled to France or North Africa.

Despite early Christian testimonies and institutional organization, Christianization of the

Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

was slow. Muslim accounts from the period of the

Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, also known as the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, was the initial expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate over Hispania (in the Iberian Peninsula) from 711 to 718. The conquest resulted in the decline of t ...

(711 – 718) up to the 9th century, indicate the Basques were not considered Christianized by the Muslims who called them ''magi'' or 'pagan wizards', rather than '

People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

' as Christians or Jews were.

Colonialization and secularization

Christianity and the various pagan religions co-existed and largely tolerated each other in most of the empire throughout the majority of the fourth and fifth centuries. The structure and ideals of both Church and State were transformed through this long period of symbiosis. By the time a fifth-century pope attempted to denounce the

Lupercalia

Lupercalia was a pastoral festival of Ancient Rome observed annually on February 15 to purify the city, promoting health and fertility. Lupercalia was also known as ''dies Februatus'', after the purification instruments called ''februa'', the b ...

as 'pagan superstition', religion scholar

Elizabeth Clark says "it fell on deaf ears". In Historian

R. A. Markus's reading of events, this marked a colonialization by Christians of pagan values and practices. For Alan Cameron, the mixed culture that included the continuation of the circuses, amphitheaters and games – sans sacrifice – on into the sixth century involved the secularization of paganism rather than appropriation by Christianity.

Up to the time of Justin I and Justinian I (527 to 565), there was some toleration for all religions; there were anti-sacrifice laws, but they were not enforced. Thus, up into the sixth century, there still existed centers of paganism in Athens, Gaza, Alexandria, and elsewhere.

Christianization of Europe (6th–9th centuries)

End of the ancient world

A seismic shift in Christianization took place in 612 when the Visigothic

King Sisebut declared the obligatory conversion of all Jews in Spain, contradicting Pope Gregory who had, consistent with tradition, explicitly opposed forced conversion in 591. Scholars refer to this shift as a "seismic moment" in Christianization because of its long lasting and extensive reverberations. It is representative of the power struggle between state and church that began under

Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''Augustus (title), augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after ...

and fully manifested under

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

, with the state taking control of religion.

Constantine had granted, through the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, the right to all to follow whatever religion they wished, and Gratian surrendered the title of

Pontifex Maximus, whereas the religious policy of the Eastern emperor

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(527 to 565) reflected his conviction that a unified Empire presupposed unity of faith - his faith. Again, unlike the Western Christian emperors, Justinian purged the bureaucracy of those who disagreed with him. Herrin asserts that, under Justinian, this involved considerable destruction. The decree of 528 had already barred pagans from state office when, decades later, Justinian ordered a "persecution of surviving Hellenes, accompanied by the burning of pagan books, pictures and statues" which took place at the ''Kynêgion''. Herrin says it is difficult to assess the degree to which Christians are responsible for the losses of ancient documents in many cases, but in the mid-sixth century, active persecution in Constantinople destroyed many ancient texts.

According to

Anthony Kaldellis

Anthony Kaldellis ( gr, Αντώνιος Καλδέλλης; born 29 November 1971) is a Greek historian who is Professor and a faculty member of the Department of Classics at the University of Chicago. He is a specialist in Greek historiograph ...

, Justinian is often seen as a tyrant and despot. He sought to centralize imperial government, became increasingly autocratic, and "nothing could be done", not even in the Church, that was contrary to the emperor's will and command. In Kaldellis' estimation, "Few emperors had started so many wars or tried to enforce cultural and religious uniformity with such zeal".

In the first half of the sixth century, Justinian came to Rome to liberate it from barbarians leading to a guerrilla war that lasted nearly 20 years. After fighting ended, Justinian used what is known as a ''

Pragmatic Sanction

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

When used ...

'' to assert control over Italy. The Sanction effectively removed the supports that had allowed the senatorial aristocracy to retain power. The political and social influence of the Senate's aristocratic members thereafter disappeared, and by 630, the Senate ceased to exist, and its building was converted into a church. Bishops stepped into civic leadership in the Senator's places. The position and influence of the pope rose.

Before the 800s, the 'Bishop of Rome' had no special influence over other bishops outside of Rome, and had not yet manifested as the central ecclesiastical power. There were regional versions of Christianity accepted by local clergy that it's probable the papacy would not have approved of – if they had been informed.

From the late seventh to the middle of the eighth century, eleven of the thirteen men who held the position of Roman Pope were the sons of families from the East. Before they could be installed, these Popes had to be approved by the head of State, the Byzantine emperor. The union of church and state buoyed both, while the

Byzantine papacy

The Byzantine Papacy was a period of Byzantine domination of the Roman papacy from 537 to 752, when popes required the approval of the Byzantine Emperor for episcopal consecration, and many popes were chosen from the '' apocrisiarii'' (liaisons ...

, along with losses to Islam, and corresponding changes within Christianity itself, put an end to Ancient Christianity. Most scholars agree the 7th and 8th centuries are when the 'end of the ancient world' is most conclusive and well documented. Christianity changed as it transformed into its eclectic medieval forms as exemplified by the creation of the

Papal state

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, and the alliance between the papacy and the militant Frankish king

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

.

Bulgaria

Christianity had taken root in the Balkans when it was part of the Roman Empire. When the

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

entered the area and conquered it in the fifth century, they adopted the religion of those they had subdued. In 680,

Khan Aspuruk, the leader of an ethnically mixed pagan tribe, possibly from central Asia, and possibly of Turkish origin, led an army of Proto-Bulgars across the Danube, conquering the Slavs. They settled, and the First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 680/1 with the capitol at

Pliska

Pliska ( , cu, Пльсковъ, translit=Plĭskovŭ) was the first capital of the First Bulgarian Empire during the Middle Ages and is now a small town in Shumen Province, on the Ludogorie plateau of the Danubian Plain, 20 km northeast o ...

. Over the next two centuries, they fought on and off to protect their borders from various tribes and Byzantium.

[Ziemann, Daniel. "Goodness and Cruelty: The Image of the Ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire in the Period of Christianisation (Ninth Century)." The Good Christian Ruler in the First Millennium. De Gruyter, 2021. 327-360.]

Omurtag

Omurtag (or Omortag) ( bg, Омуртаг; original gr, Μορτάγων and Ομουρτάγ', Inscription No.64. Retrieved 10 April 2012.) was a Great Khan ('' Kanasubigi'') of Bulgaria from 814 to 831. He is known as "the Builder".

In the v ...

became Khan in 814. He persecuted Christians, but war with Byzantium, and other wars to acquire territory, brought many Christian prisoners of war into the state. The histories say their faith in the face of extreme misery impressed some of their captors including one of Omurtag's sons who converted. Under Omurtag, Bulgaria and Byzantium maintained a 30-year peace treaty that allowed for more contact, and this increased Christian missionary activities.

Christianity spread, while the nobility who were largely Proto-Bulgarians, remained steadfastly pagan.

Official Christianization began in 864/5 under

Khan Boris I (852– 889) who had been baptized in 864 in the capital city, Pliska, by Byzantine priests.

The need to secure the country's borders, at least from Byzantium, was compounded by the need for internal peace between the different ethnic groups. Boris I determined that imposing Christianity was the answer.

[Crampton, Richard J. A concise history of Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press, 2005.] The decision was partly military, partly domestic, and partly to diminish the power of the Proto-Bulgarian nobility. A number of nobles reacted violently; 52 were executed. After prolonged negotiations with both Rome and Constantinople, an

autocephalous

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Ort ...

Bulgarian Orthodox Church was formed that used the newly created

Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ), Slavonic script or the Slavic script, is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, ...

to make the Bulgarian language the language of the Church.

Boris' eldest son, Vladimir, also called Rasate, probably ruled from 889 – 893. He was deposed in 893 amidst accusations he was planning to abandon the Christian faith. Scholars remain uncertain as to the veracity of the accusation.

His younger brother

Symeon, Boris' third son, replaced him, ruling from 893 to 927. He intensified the translation of Greek literature and theology into Bulgarian, and enabled the establishment of an intellectual circle called

the school of Preslav.

Symeon also led a series of wars against the Byzantines to gain official recognition of his Imperial title and the full independence of the Bulgarian Church. As a result of his victories in 927, the Byzantines finally recognized the

Bulgarian Patriarchate

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church ( bg, Българска православна църква, translit=Balgarska pravoslavna tsarkva), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria ( bg, Българска патриаршия, links=no, translit=Balgarsk ...

.

Serbia

The

Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.