Chesterfield Group on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chesterfield Islands (''îles Chesterfield'' in French) are a French

The Chesterfield Islands (''îles Chesterfield'' in French) are a French

Captain Matthew Boyd of ''

Captain Matthew Boyd of ''

Long Island , 10 nm NW of Loop Islet, is the largest of the Chesterfield Islands, and is 1400 to 1800 m long but no more than 100 m across and 9 m high. In May 1859

Long Island , 10 nm NW of Loop Islet, is the largest of the Chesterfield Islands, and is 1400 to 1800 m long but no more than 100 m across and 9 m high. In May 1859

The Chesterfield Islands (''îles Chesterfield'' in French) are a French

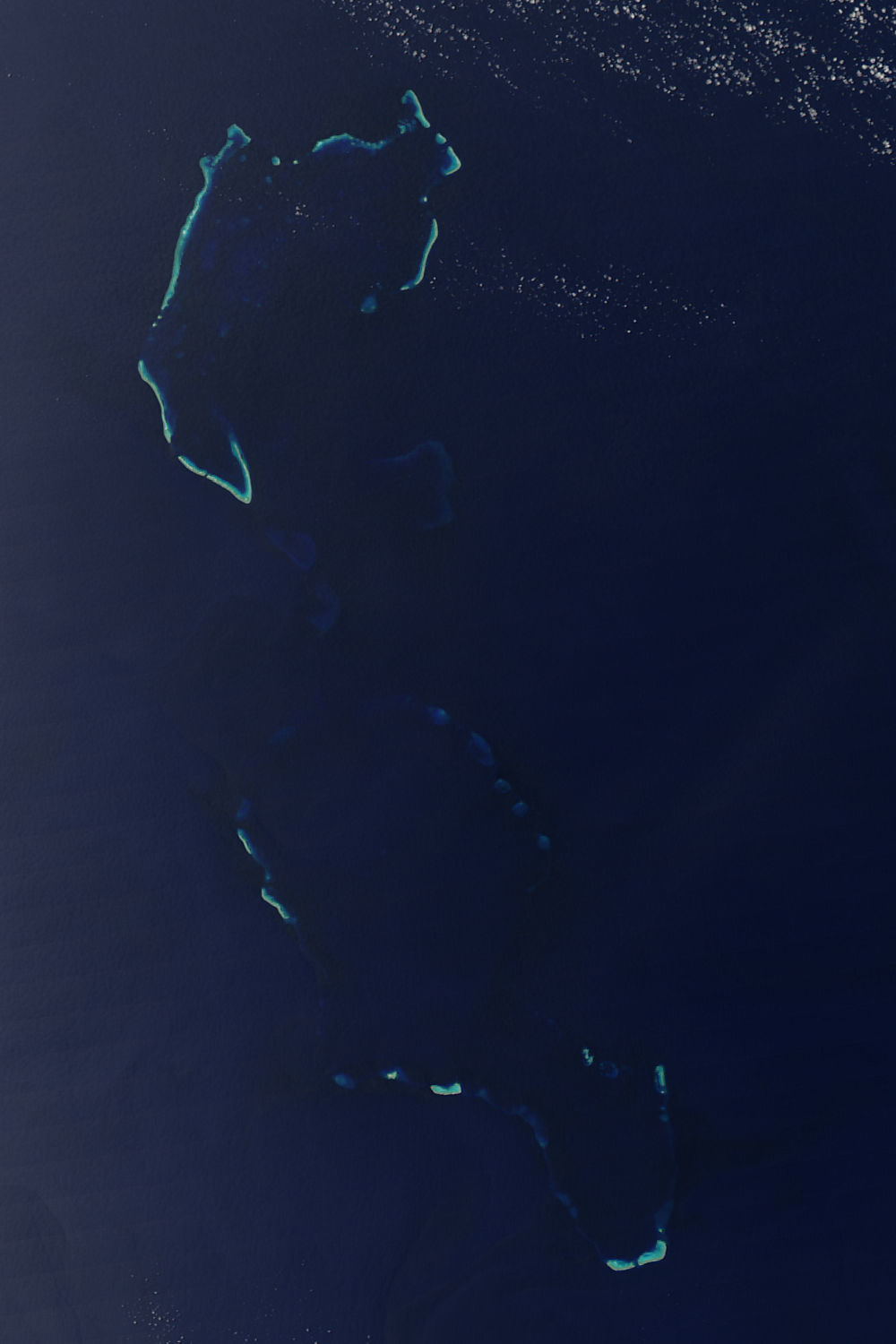

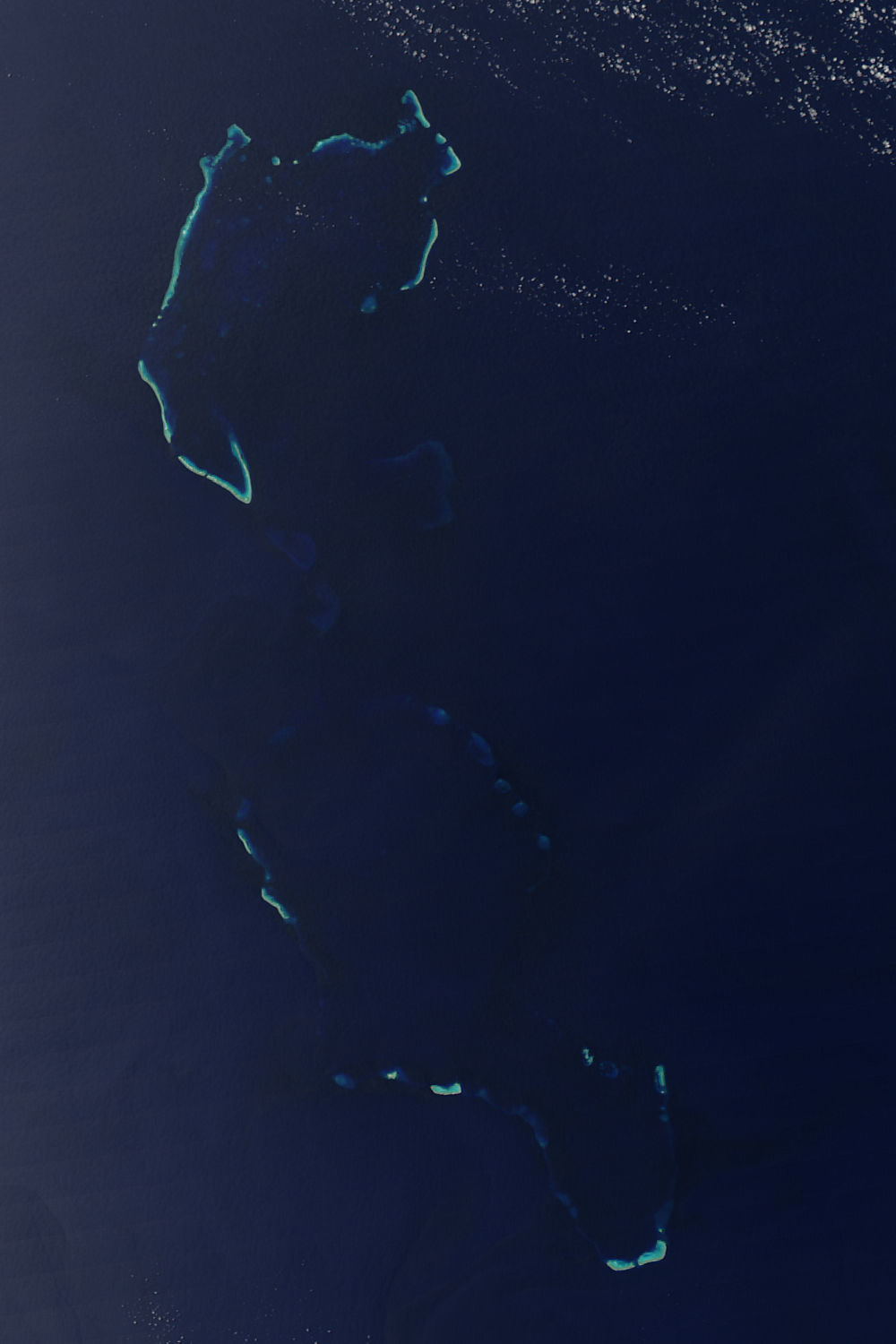

The Chesterfield Islands (''îles Chesterfield'' in French) are a French archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arch ...

of New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

located in the Coral Sea

The Coral Sea () is a marginal sea of the South Pacific off the northeast coast of Australia, and classified as an interim Australian bioregion. The Coral Sea extends down the Australian northeast coast. Most of it is protected by the Fre ...

, northwest of Grande Terre, the main island of New Caledonia. The archipelago is 120 km long and 70 km broad, made up of 11 uninhabited islets and many reefs. The land area of the islands is less than 10 km2.

During periods of lowered sea level during the Pleistocene ice ages, an island of considerable size (Greater Chesterfield Island) occupied the location of the archipelago.

Bellona Reef, 164 km south-southeast of Chesterfield, is geologically separated from the Chesterfield archipelago but commonly included.

Etymology

The reef complex is named after thewhaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

ship , commanded by Matthew Bowes Alt, which sailed through the Coral Sea

The Coral Sea () is a marginal sea of the South Pacific off the northeast coast of Australia, and classified as an interim Australian bioregion. The Coral Sea extends down the Australian northeast coast. Most of it is protected by the Fre ...

in the 1790s.

Location

The Chesterfield Islands, sometimes referred to as the ''Chesterfield Reefs'' or ''Chesterfield Group'', are the most important of a number of uninhabitedcoral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

sand cays

A cay ( ), also spelled caye or key, is a small, low-elevation, sandy island on the surface of a coral reef. Cays occur in tropical environments throughout the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, including in the Caribbean and on the Great ...

. Some are awash and liable to shift with the wind while others are stabilized by the growth of grass, creepers and low trees. The reefs extend from 19˚ to 22˚S between 158– 160˚E in the southern Coral Sea halfway between Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and New Caledonia. The Chesterfield Reefs are now part of the territory of New Caledonia while the islands farther west are part of the Australian Coral Sea Islands

The Coral Sea Islands Territory is an external territory of Australia which comprises a group of small and mostly uninhabited tropical islands and reefs in the Coral Sea, northeast of Queensland, Australia. The only inhabited island is W ...

Territory.

Chesterfield lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

, located between 19˚00' and 20˚30' S and 158˚10' and 159˚E covers an area of approximately 3500 km2. A barrier reef surrounds the lagoon, interrupted by wide passes except on its eastern side where it is open for over . The major part of the lagoon is exposed to trade winds and to the southeastern oceanic swell. The lagoon is relatively deep with a mean depth of 51 m. The depth increases from south to north.

Chesterfield Reefs complex consists of the Bellona Reef complex to the south (South, Middle and Northwest Bellona Reef) and the Bampton Reef complex.

Bellona Reefs

Captain Matthew Boyd of ''

Captain Matthew Boyd of ''Bellona Bellona may refer to:

Places

*Bellona, Campania, a ''comune'' in the Province of Caserta, Italy

*Bellona Reef, a reef in New Caledonia

*Bellona Island, an island in Rennell and Bellona Province, Solomon Islands

Ships

* HMS ''Bellona'' (1760), a 74 ...

'' named the reefs for his ship. He had delivered convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convict ...

s to New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

in 1793 and was on his way to China to pick up a cargo at Canton to take back to Britain for the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

when he passed the reefs in February–March 1793.

*West Point ,

*Olry Reef , on the south an unvegetated sand cay ''Caye Est Bellona''

*Middle Bellona Reefs ,

*Observatory Cay ,

*Booby Reef ,

*Northwest Bellona Reef ,

*Noel Bank ,

*South Bellona Reef or West Point , Approximately 3 m tall sand islet, reported to be non-existent by 1988 ( Sailing Directions)

Lieutenant John Lamb, R.N., Commander of the ship '' Baring'', spent three days in the neighborhood of Booby and Bellona Shoals and reefs. Lamb took soundings between nineteen and forty-five fathoms (114–270 ft), and frequently passed shoals, upon which the sea was breaking. Lamb defined the limits of the rocky ground as the parallels of 20°40' and 21°50' and the meridians of 158°15' and 159°30'. He also saw a sandy islet, surrounded by a chain of rocks, at 21°24½′ south and 158°30' east. The ship ''Minerva'' measured the water's depth as eight fathoms (48 ft), with the appearance of shallower water to the southwest; this last danger is in a line between the two shoals at about longitude 159°20' east, as described by James Horsburgh

James Horsburgh (28 September 176214 May 1836) was a Scottish hydrographer. He worked for the British East India Company, (EIC) and mapped many seaways around Singapore in the late 18th century and early 19th century.

Life

Born at Elie, Fife, Hor ...

.

Observatory Cay (Caye de l'Observatoire) , 800 m long and 2 m high, lies on the Middle Bellona Reefs at the southern end of the Chesterfield Reefs and 180 nm east of Kenn Reef.

Minerva Shoal

*Minerva Shoal,Chesterfield Reefs

*South Elbow or Loop Islet, *Anchorage Islets , *Passage Islet (Bennett Islet), *Long Island , The Chesterfield Reefs is a loose collection of elongated reefs that enclose a deep, semi-sheltered, lagoon. The reefs on the west and northwest are known as the Chesterfield Reefs; those on the east and north being the Bampton Reefs. The Chesterfield Reefs form a structure measuring 120 km in length (northeast to southwest) and 70 km across (east to west). There are numerous cays occurring amongst the reefs of both the Chesterfield and Bampton Reefs. These include: Loop Islet, Renard Cay, Skeleton Cay, Bennett Island, Passage Islet, Veys Islet, Long Island, the Avon Isles, the Anchorage Islets and Bampton Island. Long Island , 10 nm NW of Loop Islet, is the largest of the Chesterfield Islands, and is 1400 to 1800 m long but no more than 100 m across and 9 m high. In May 1859

Long Island , 10 nm NW of Loop Islet, is the largest of the Chesterfield Islands, and is 1400 to 1800 m long but no more than 100 m across and 9 m high. In May 1859 Henry Mangles Denham

Vice Admiral Sir Henry Mangles Denham (28 August 1800 – 3 July 1887) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station.

Early career

Denham entered the navy in 1809. He served on from 1810 to 1814, initially u ...

found Long Island was "a heap of 'foraminifera' densely covered with stunted bush‑trees with leaves as large as cabbage plants, spreading 12 feet (3.7 m) and reaching as high, upon trunks 9 inches (23 cm) diameter... The trees around the margin of this island were leafless, as if from the sea‑fowl." Although wooded in the 1850s, it was stripped during guano extraction in the 1870s and was said to be covered in grass with only two coconut trees and some ruins at the south end early in the 20th century. The vegetation was growing again by 1957 when the remaining ruins were confused with those of a temporary automatic meteorological station established in the same area by the Americans between 1944 and 1948. Terry Walker reported that by 1990 there was a ring of low Tournefortia trees growing around the margin, herbs, grass and shrubs in the interior, and still a few exotic species including coconuts.

South of Long Island and Loop Islet there are three small low islets (Martin, Veys and Passage islets) up to 400 m across followed, after a narrow channel, by Passage or Bennett Island, which is 12 m high and was a whaling station in the first half of the 20th century. Several sand cays lie on the reef southeast of the islet.

Avon Isles

*Avon Isles (Northwest Point) , *Avon Isles (south) The two Avon Isles , some 188 m in diameter and 5 m high to the top of the dense vegetation, are situated 21 n.m. north of Long Island. They were seen by Mr. Sumner, Master of the ship ''Avon'', on 18 September 1823, and are described by him as being three-quarters of a mile in circumference, twenty feet high, and the sea between them twenty fathoms deep. At four miles (7 km) northeast by north from them the water was twelve fathoms (72 feet) deep, and at the same time they saw a reef ten or fifteen miles (20–30 km) to the southeast, with deep water between it and the islets. A boat landed on the south-westernmost islet, and found it inhabited only by birds, but clothed with shrubs and wild grapes. By observation, these islands were found to lie in latitude 19 degrees 40 minutes, and longitude 158 degrees 6 minutes. The Avon Isles are described by Denham in 1859 as "densely covered with stunted trees and creeping plants and grass, and... crowded with the like species of birds."Bampton Reefs

*Bampton Reefs *Bampton Island , *North Bampton Reef , *Northeast Bampton Reef , *Renard Island , *Skeleton Cay Renard Island North Bampton Reef , Approximately tall sand islet lies northeast of the Avon Isles and is long, across and also high to the top of the bushes. Southeast Bampton Reef Sand Cay elevation Loop Islet , which lies 85 nm farther north near the south end of the central islands of Chesterfield Reefs, is a small, flat, bushy islet 3 m high where a permanent automatic weather station was established by the Service Météorologique de Nouméa in October 1968. Terry Walker reported the presence of a grove of Casuarinas in 1990. Anchorage Islets are a group of islets five nautical miles (9 km) north of Loop Islet. The third from the north, about 400 m long and 12 m high, shelters the best anchorage. Passage (Bonnet) Island reaches a vegetative height of 12 m Bampton Island , lies on Bampton Reefs 20 nm NW of Renard Island. It is 180 m long, 110 m across and 5 m high. It had trees when discovered in 1793, but has seldom been visited since then except by castaways. The reefs and islands west of the Chesterfield Islands, the closest being Mellish Reef with Herald's Beacon Islet at , at a distance of 180 nm northwest of Bampton Island, belong to theCoral Sea Islands Territory

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secre ...

.

Important Bird Area

The Bampton and Chesterfield Reef Islands, with their surrounding waters, have been recognised as anImportant Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

(IBA) by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding ...

because they support breeding colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

of several species of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s, including lesser frigatebird

The lesser frigatebird (''Fregata ariel'') is a seabird of the frigatebird family Fregatidae. At around 75 cm (30 in) in length, it is the smallest species of frigatebird. It occurs over tropical and subtropical waters across the Indian ...

s, red-footed and brown boobies

The brown booby (''Sula leucogaster'') is a large seabird of the booby family Sulidae, of which it is perhaps the most common and widespread species. It has a pantropical range, which overlaps with that of other booby species. The gregarious brow ...

, brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model used ...

and black noddies, and fairy tern

The fairy tern (''Sternula nereis'') is a small tern which is native to the southwestern Pacific. It is listed as " Vulnerable" by the IUCN and the New Zealand subspecies is " Critically Endangered".

There are three subspecies:

* Australian fai ...

s.

History

18th Century

Booby Reef in the center of the eastern chain of reefs and islets comprising Chesterfield Reefs appears to have been discovered first by Lt.Henry Lidgbird Ball

Henry Lidgbird Ball (7 December 1756 – 22 October 1818) was a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy of the British Empire. While Ball was best known as the commander of the First Fleet's , he was also notable for the exploration and the establishmen ...

in HMS ''Supply'' on the way from Sydney to Batavia (modern day Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coast of Java, the world's most populous island, Jakarta ...

) in 1790. The reefs to the south were found next by Mathew Boyd in the convict ship ''Bellona'' on his way from Sydney to Canton (modern day Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

) in February or March 1793.

The following June, William Wright Bampton became embayed for five days at the north end of Chesterfield Reefs in the Indiaman

East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship operating under charter or licence to any of the East India Company (disambiguation), East India trading companies of the major European trading powers of the 17th through the 19th centuries ...

''Shah Hormuzeer'', together with Mathew Bowes Alt in the whaler ''Chesterfield''.

Bampton reported two islets with trees and "a number of birds of different species around the ships, several of them the same kind as at Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

”.

19th Century

The reefs continued to present a hazard to shipping plying between Australia and Canton orIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(where cargo was collected on the way home to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

). The southern reefs were surveyed by Captain Henry Mangles Denham

Vice Admiral Sir Henry Mangles Denham (28 August 1800 – 3 July 1887) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station.

Early career

Denham entered the navy in 1809. He served on from 1810 to 1814, initially u ...

in the ''Herald'' from 1858 to 1860.

He made the natural history notes discussed below. The northern reefs were charted by Lieutenant G.E.Richards in HMS ''Renard'' in 1878 and the French the following year. Denham's conclusions are engraved on British Admiralty Chart 349:

The area is a wintering ground for numerous Humpback whales

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hump ...

and smaller numbers of Sperm whales

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

. During the 19th century the Chesterfield Islands were visited by increasing numbers of whalers during the off season in New Zealand. L. Thiercelin reported that in July 1863 the islets only had two or three plants, including a bush 3–4 m high, and were frequented by turtles weighing 60 to 100 kg. Many eggs were being taken regularly by several English, two French and one American whaler. On another occasion there were no less than eight American whalers. A collection of birds said to have been made by Surgeon Jourde of the French whaler ''Général d’Hautpoul'' on the Brampton Shoals in July 1861 was subsequently brought by Gerard Krefft (1862) to the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

, but clearly not all the specimens came from there.

On 27 October 1862, the British Government granted an exclusive concession to exploit the guano on Lady Elliot Island

Lady Elliot Island is the southernmost coral cay of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. The island lies north-east of Bundaberg and covers an area of approximately . It is part of the Capricorn and Bunker Group of islands and is owned by the C ...

, Wreck Reef, Swain Reefs, Raine Island

Raine Island is a vegetated coral cay in total area situated on the outer edges of the Great Barrier Reef off north-eastern Australia. It lies approximately north-northwest of Cairns in Queensland, about east-north-east of Cape Grenville on ...

, Bramble Cay, Brampton Shoal, and Pilgrim Island to the Anglo Australian Guano Company organized by the whaler Dr. William Crowther in Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. They were apparently most active on Bird Islet (Wreck Reef) and Lady Elliot and Raine Islands (Hutchinson, 1950), losing five ships at Bird Islet between 1861 and 1882 (Crowther 1939). It is not clear that they ever took much guano from the Chesterfield Islands unless it was obtained from Higginson, Desmazures et Cie, discussed below.

When in 1877 Joshua William North also found guano on the Chesterfield Reefs, Alcide Jean Desmazures persuaded Governor Orly of New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

to send the warship ''La Seudre'' to annex them. There were estimated to be about 185,000 cu m of guano on Long Island and a few hundred tons elsewhere, and 40% to 62% phosphate (Chevron, 1880), which was extracted between 1879 and 1888 by Higginson, Desmazures et Cie of Nouméa (Godard, nd), leaving Long Island stripped bare for a time (Anon., 1916).

20th and 21st Century

Apparently the islands were then abandoned until Commander Arzur in the French warship ''Dumont d’Urville'' surveyed the Chesterfield Reefs and erected a plaque in 1939. In September 1944, American forces installed a temporary automatic meteorological station at the south end of Long Island, which was abandoned again at the end of World War II. The first biological survey was made of Long Island by Cohic during four hours ashore on 26 September 1957. It revealed, among other things, a variety of avian parasites including a widespread ''Ornithodoros'' tick belonging to a genus carryingarbovirus

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term ''arbovirus'' is a portmanteau word (''ar''thropod-''bo''rne ''virus''). ''Tibovirus'' (''ti''ck-''bo''rne ''virus'') is sometimes used to more spe ...

es capable of causing illness in humans. This island and the Anchorage Islets were also visited briefly during a survey of New Caledonian coral reefs in 1960 and 1962.

An aerial magnetic survey was made of the Chesterfield area in 1966, and a seismic survey in 1972, which apparently have not been followed up yet. In November 1968 another automatic meteorological station was installed on Loop Islet where 10 plants were collected by A.E. Ferré. Since then the Centre de Nouméa of the Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre Mer has arranged for periodic surveys and others when this installation is serviced.

From 1982 to 1992 Terry Walker carried out methodical surveys of the Coral Sea islets with the intention of producing a seabird atlas. He visited the central islands of the Chesterfield Reefs in December 1990.

An amateur radio DX-pedition

A DX-pedition is an expedition to what is considered an exotic place by amateur radio operators and DX listeners, typically because of its remoteness, access restrictions, or simply because there are very few radio amateurs active from that pl ...

(TX3X) was conducted on one of the islands in October 2015.

Known Shipwrecks on the Reef

Unless otherwise noted, information in this section is from ''Coral Sea and Northern Great Barrier Reef Shipwrecks.''References

Further reading

*Bateson, Charles. ''Australian shipwrecks Vol. 1 1622–1850,'' (print), Sydney: Reed. *Borsa, Philippe, Mireille Pandolfi, Serge Andréfouët, and Vincent Bretagnolle. "Breeding Avifauna of the Chesterfield Islands, Coral Sea: Current Population Sizes, Trends, and Threats." ''Pacific Science'' vol. 64, Issue 2. pp. 297–314. *Cohic, F. (1959) "Report on a Visit to the Chesterfield Islands, September 1957." ''Atoll Research Bulletin'' No. 63 (15 May 1959). http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/atollresearchbulletin/issues/00063.pdf. Accessed 4-19-2013. *Findlay, A. (1851) ''A Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean,'' (print), London. *Harding, John. ''THE CORAL SEA...French Territory.'' (web). https://web.archive.org/web/20081203124528/http://www.thejohnharding.com/archives/00001639.htm. Accessed 4-19-2013. Photograph from Loop Island. *Loney, J. K. (1987) ''Australian shipwrecks Vol. 4 1901–1986,'' (print), Portarlington, Victoria: Marine History Publications. *Loney, J. K. (1991) ''Australian shipwrecks Vol. 5 Update 1986,'' (print), Portarlington, Victoria: Marine History Publications. {{authority control Islands of New Caledonia Landforms of the Coral Sea Important Bird Areas of New Caledonia Seabird colonies