Charmides (poem) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Charmides'' was

''Charmides'' was

The name of Wilde's poem and its hero is identical with that of a young man loved by

The name of Wilde's poem and its hero is identical with that of a young man loved by

''Charmides'' was

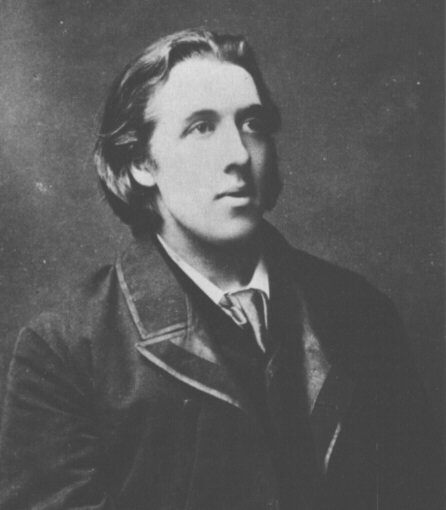

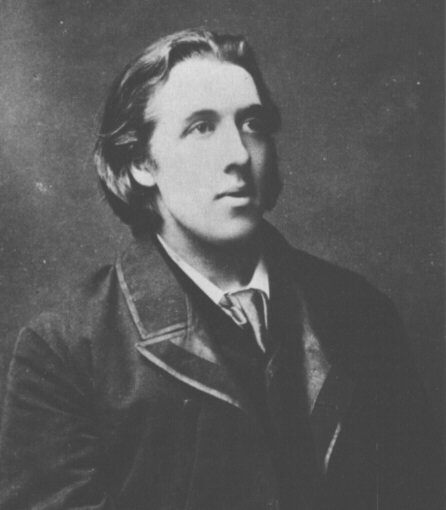

''Charmides'' was Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

's longest and one of his most controversial poems. It was first published in his 1881 collection ''Poems''. The story is original to Wilde, though it takes some hints from Lucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed superstiti ...

and other ancient writers; it tells a tale of transgressive sexual passion in a mythological setting in ancient Greece. Contemporary reviewers almost unanimously condemned it, but modern assessments vary widely. It has been called "an engaging piece of doggerel", a "comic masterpiece whose shock-value is comparable to that of Manet

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) or mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre-existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points ...

's ''Olympia

The name Olympia may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Olympia'' (1938 film), by Leni Riefenstahl, documenting the Berlin-hosted Olympic Games

* ''Olympia'' (1998 film), about a Mexican soap opera star who pursues a career as an athlet ...

'' and '' Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe''", and "a Decadent

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in social norm, standards, morality, morals, dignity, religion, religious faith, honor, discipline, or competen ...

poem ''par excellence''" in which " e illogicality of the plot and its '' deus-ex-machina'' resolution render the poem purely decorative". It is arguably the work in which Wilde first found his own poetic voice.

Synopsis

Charmides, a Greek youth, disembarks from the ship which has brought him back fromSyracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

**North Syracuse, New York

*Syracuse, Indiana

* Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, Miss ...

, and climbs up to his native village in the Greek mountains where there is a shrine dedicated to Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of ...

. He hides himself and, unnoticed by the priest and local rustics, watches while offerings are made to the goddess, until with nightfall he is left alone. He flings open the temple door to discover the carven image of virginal Athena within; he undresses it, kisses its lips and body, and spends the whole night there, "nor cared at all his passion's will to check". At daybreak he returns to the lowlands and falls asleep by a stream, where most of those who see him mistake him for some woodland god on whose privacy it would be unsafe to intrude. On awaking, Charmides makes his way to the coast and takes ship. Nine days out to sea his ship encounters first a great owl, then the gigantic figure of Athena herself striding across the sea. Charmides cries "I come", and leaps into the sea hoping to reach the goddess, but instead drowns.

Charmides' body is drawn back to Greece by "some good Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

-god" and washed up on a stretch of the Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a '' loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

shore much haunted by mythological beings. He is discovered by a band of dryads

A dryad (; el, Δρυάδες, ''sing''.: ) is a tree nymph or tree spirit in Greek mythology. ''Drys'' (δρῦς) signifies "oak" in Greek, and dryads were originally considered the nymphs of oak trees specifically, but the term has evolved to ...

, who all flee in terror except one, who is besotted by the boy's beauty and who thinks him a sleeping sea-deity rather than a three days dead human boy. She dreams of their future life together in majesty under the sea, and renounces the love of a shepherd boy who has been courting her. Fearful of her mistress's anger she repeatedly urges Charmides to awake and take her virginity, but it is too late: the goddess Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

transfixes the dryad with an arrow. The dead Charmides and dying nymph are discovered by Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

just before the nymph breathes her last. Venus then prays to Proserpine

Charmides awakes in the dreary realm of Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

, the Greek underworld

In mythology, the Greek underworld, or Hades, is a distinct realm (one of the three realms that makes up the cosmos) where an individual goes after death. The earliest idea of afterlife in Greek myth is that, at the moment of death, an individ ...

, to discover the nymph beside him, and they make love. The poem ends with a celebration of the marvel that this notable sinner could at last find love in a loveless place.

Publication

''Charmides'' was written in late 1878 or early 1879. It first appeared inWilde

Wilde is a surname. Notable people with the name include:

In arts and entertainment In film, television, and theatre

* ''Wilde'' a 1997 biographical film about Oscar Wilde

* Andrew Wilde (actor), English actor

* Barbie Wilde (born 1960), Canadi ...

's ''Poems'' (1881), a single volume published by David Bogue at the author's expense in an edition of 250 copies. Two further editions followed the same year. There were a fourth and fifth edition in 1882, though in these two stanzas were removed, perhaps in response to public reaction; they were not reinstated until Robert Ross's 1908 edition of ''The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde''. In 1892 Wilde, now famous as the author of ''Lady Windermere's Fan

''Lady Windermere's Fan, A Play About a Good Woman'' is a four-act comedy by Oscar Wilde, first performed on Saturday, 20 February 1892, at the St James's Theatre in London.

The story concerns Lady Windermere, who suspects that her husband i ...

'', had his ''Poems'' reissued by The Bodley Head

The Bodley Head is an English publishing house, founded in 1887 and existing as an independent entity until the 1970s. The name was used as an imprint of Random House Children's Books from 1987 to 2008. In April 2008, it was revived as an adul ...

as a sumptuous limited edition with a decorative binding and frontispiece by Charles Ricketts

Charles de Sousy Ricketts (2 October 1866 – 7 October 1931) was a British artist, illustrator, author and printer, known for his work as a book designer and typographer and for his costume and scenery designs for plays and operas.

Ricketts ...

. This incarnation of the ''Poems'' as an ''objet d'art'' in itself is, it has been argued, the ideal setting for the self-consciously Decadent

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in social norm, standards, morality, morals, dignity, religion, religious faith, honor, discipline, or competen ...

''Charmides''.

Metre

The metre in which Wilde wrote ''Charmides'' is based on that of Shakespeare's '' Venus and Adonis''. Each stanza has six lines rhyming ABABCC, the first five lines being iambic pentameters while the last one is extended to ahexameter

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek and Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of syllables). It w ...

.

Sources

The name of Wilde's poem and its hero is identical with that of a young man loved by

The name of Wilde's poem and its hero is identical with that of a young man loved by Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

and immortalised in Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's dialogue ''Charmides

Charmides (; grc-gre, Χαρμίδης), son of Glaucon, was an Athenian statesman who flourished during the 5th century BC.Debra Nails, ''The People of Plato'' (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), 90–94. An uncle of Plato, Charmides appears i ...

''. Wilde may have intended the name to be a signal to his readers that the poem is an erotically charged work about a beautiful boy, but there is no other connection between the two works, whether verbal or thematic. The first part of Wilde's story was suggested by an anecdote in Lucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed superstiti ...

's ''Essays in Portraiture'' concerning a young man who became obsessed with Praxiteles

Praxiteles (; el, Πραξιτέλης) of Athens, the son of Cephisodotus the Elder, was the most renowned of the Attica sculptors of the 4th century BC. He was the first to sculpt the nude female form in a life-size statue. While no indubita ...

' statue of Aphrodite and sexually assaulted it, though Wilde made the story still more transgressive by substituting the chaste goddess Athena for Lucian's Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols include ...

. He probably also had in mind the words of Walter Pater

Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was an English essayist, art critic and literary critic, and fiction writer, regarded as one of the great stylists. His first and most often reprinted book, ''Studies in the History of the Re ...

on the Hellenist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient ...

Winckelmann Winckelmann may refer to:

* George Winckelmann (1884–1962), a Finnish lawyer and a diplomat

* Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), a German art historian and archaeologist

* Johann Just Winckelmann

Johann Just Winckelmann (19 August 1620 ...

, who "fingers those pagan marbles with unsinged hands, with no sense of shame or loss". In the same essay Pater assures us that "Greek religion too has its statues worn with kissing". The second part of the story might have been suggested by a tale in Parthenius of Nicaea Parthenius of Nicaea ( el, Παρθένιος ὁ Νικαεύς) or Myrlea ( el, ὁ Μυρλεανός) in Bithynia was a Greeks, Greek Philologist, grammarian and poet. According to the ''Suda'', he was the son of Heraclides and Eudora, or accord ...

's ''Erotica Pathemata'' in which the Pisan

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

prince Dimoetes

In Greek mythology, Dimoetes (Ancient Greek: Διμοίτης) was a brother of Troezen (mythology), Troezen, thus presumably a son of Pelops and Hippodamia. He was married to Evopis, daughter of Troezen.

Mythology

Evopis was in love with her ow ...

finds and has sex with the body of a beautiful woman washed up on the seashore.

Stylistically, the poem owes a great deal to the influence of Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

; it has, indeed, been called "a Keatsean oasis in the Swinburnean desert" of the 1881 ''Poems''. It can also be seen to draw on the manner of William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

in '' The Earthly Paradise'' and on the more " fleshly" poems, in for example the ''House of Life'' sonnet sequence, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

.

Verbal echoes from and allusions to other poets are numerous in ''Charmides'', as in most of the 1881 ''Poems''. Reminiscences of Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, lite ...

's ''The Forsaken Merman'' and the ''Idylls'' of Theocritus

Theocritus (; grc-gre, Θεόκριτος, ''Theokritos''; born c. 300 BC, died after 260 BC) was a Greek poet from Sicily and the creator of Ancient Greek pastoral poetry.

Life

Little is known of Theocritus beyond what can be inferred from hi ...

are particularly prominent, but there also possible borrowings from the ''Odes

Odes may refer to:

*The plural of ode, a type of poem

*Odes (Horace), ''Odes'' (Horace), a collection of poems by the Roman author Horace, circa 23 BCE

*Odes of Solomon, a pseudepigraphic book of the Bible

*Book of Odes (Bible), a Deuterocanonic ...

'' of Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, Shakespeare's '' The Tempest'', Keats's "La Belle Dame sans Merci

"La Belle Dame sans Merci" ("The Beautiful Lady Without Mercy") is a ballad produced by the England, English poet John Keats in 1819. The title was derived from the title of a 15th-century poem by Alain Chartier called ''La Belle Dame sans ...

", Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

's "The Wreck of the Hesperus

"The Wreck of the Hesperus" is a narrative poem by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, first published in ''Ballads and Other Poems'' in 1842. It is a story that presents the tragic consequences of a skipper's pride. On an ill-fated voyag ...

", and Swinburne's "A Forsaken Garden".

Contemporary reception

In 1882 Wilde told the ''San Francisco Examiner

The ''San Francisco Examiner'' is a newspaper distributed in and around San Francisco, California, and published since 1863.

Once self-dubbed the "Monarch of the Dailies" by then-owner William Randolph Hearst, and flagship of the Hearst Corporat ...

'' that of all his poems ''Charmides'' was "the best...the most finished and perfect". It became, however, something of a scandal. Wilde felt obliged to drop the close friendship of his fellow-student Frank Miles

George Francis Miles (22 April 1852 – 15 July 1891) was a London-based British artist who specialised in pastel portraits of society ladies, also an architect and a keen plantsman. He was artist in chief to the magazine ''Life'', and between 1 ...

on learning that Miles's mother had cut ''Charmides'' out of her copy of ''Poems'' and that he was no longer welcome under their roof.

''Poems'' was unfavourably reviewed on its first publication, and ''Charmides'' was held up for particular vilification as the epitome of everything the critics disliked about Wilde's work. They pounced on it, a contemporary wrote, "with what in less saintly persons than reviewers would have been delight". Even Oscar Browning

Oscar Browning OBE (17 January 1837 – 6 October 1923) was a British educationalist, historian and ''bon viveur'', a well-known Cambridge personality during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. An innovator in the early development of p ...

, a personal friend whom Wilde had asked to review the book, complained in '' The Academy'' that "the story, as far as there is one, is most repulsive", and that "Mr Wilde has no magic to veil the hideousness of a sensuality which feeds on statues and dead bodies", while conceding that the poem had "music, beauty, imagination and power". Wilde was said to "greatly exceed the licence which even a past Pagan poet would have permitted himself". ''Truth

Truth is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth 2005 In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs ...

'' spoke of its "hectic immodesty". An anonymous critic in the ''Cambridge Review'' detected "a most unpleasant pervading taint of animalism". He admitted that actual indecency in the poem was restricted to the section relating to the statue, and commented sardonically that "with a statue, Mr Wilde and Charmides seem to have thought, some liberties may be taken". American reviews were, if anything, even more contemptuous. For Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823May 9, 1911) was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in the American Abolitionism movement during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with ...

, in ''Woman's Journal

''Woman's Journal'' was an American women's rights periodical published from 1870 to 1931. It was founded in 1870 in Boston, Massachusetts, by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Browne Blackwell as a weekly newspaper. In 1917 it was purchased by ...

'', ''Charmides'' was a poem which could not be read aloud in mixed company. It was, in a word, unmanly – by which he may have meant "ungentlemanly". ''The Critic'' called it "beastly", while ''Quiz: A Fortnightly Journal of Society, Literature, and Art'' thought it especially surprising that a leading Aesthete

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be prod ...

should be capable of "the coarseness which can find anything poetical in the conduct of Charmides or the smitten Dryad". ''Appletons' Journal

''Appletons' Journal'' was an American magazine of literature, science, and arts. Published by D. Appleton & Company and debuting on April 3, 1869, its first editor was Edward L. Youmans, followed by Robert Carter, Oliver Bell Bunce, and Charle ...

'' summed it up as "the most flagrantly offensive poem we remember ever to have read".

Walter Hamilton's critical study ''The Aesthetic Movement in England'' (1882) was more balanced than most of the periodical reviews had been. He wrote that ''Charmides'' "abounds with both the merits and the faults of Mr Oscar Wilde's style – it is classical, sad, voluptuous, and full of the most exquisitely musical word painting; but it is cloying for its very sweetness – the elaboration of its detail makes it over-luscious".

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

{{Authority control 1881 poems Ancient Greece in fiction Decadent literature Poetry by Oscar Wilde Works set in the Mediterranean Sea