Charles W. Fairbanks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

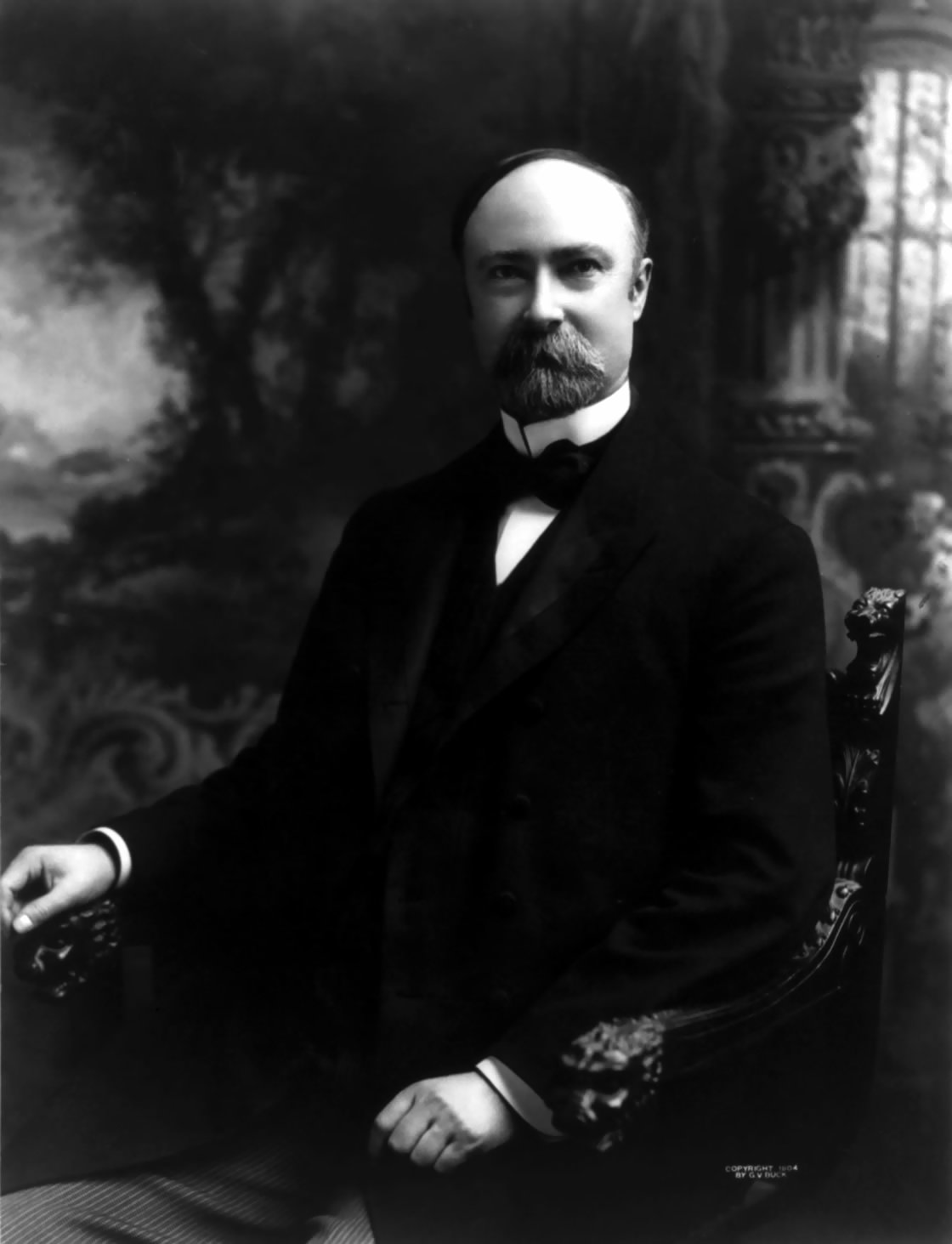

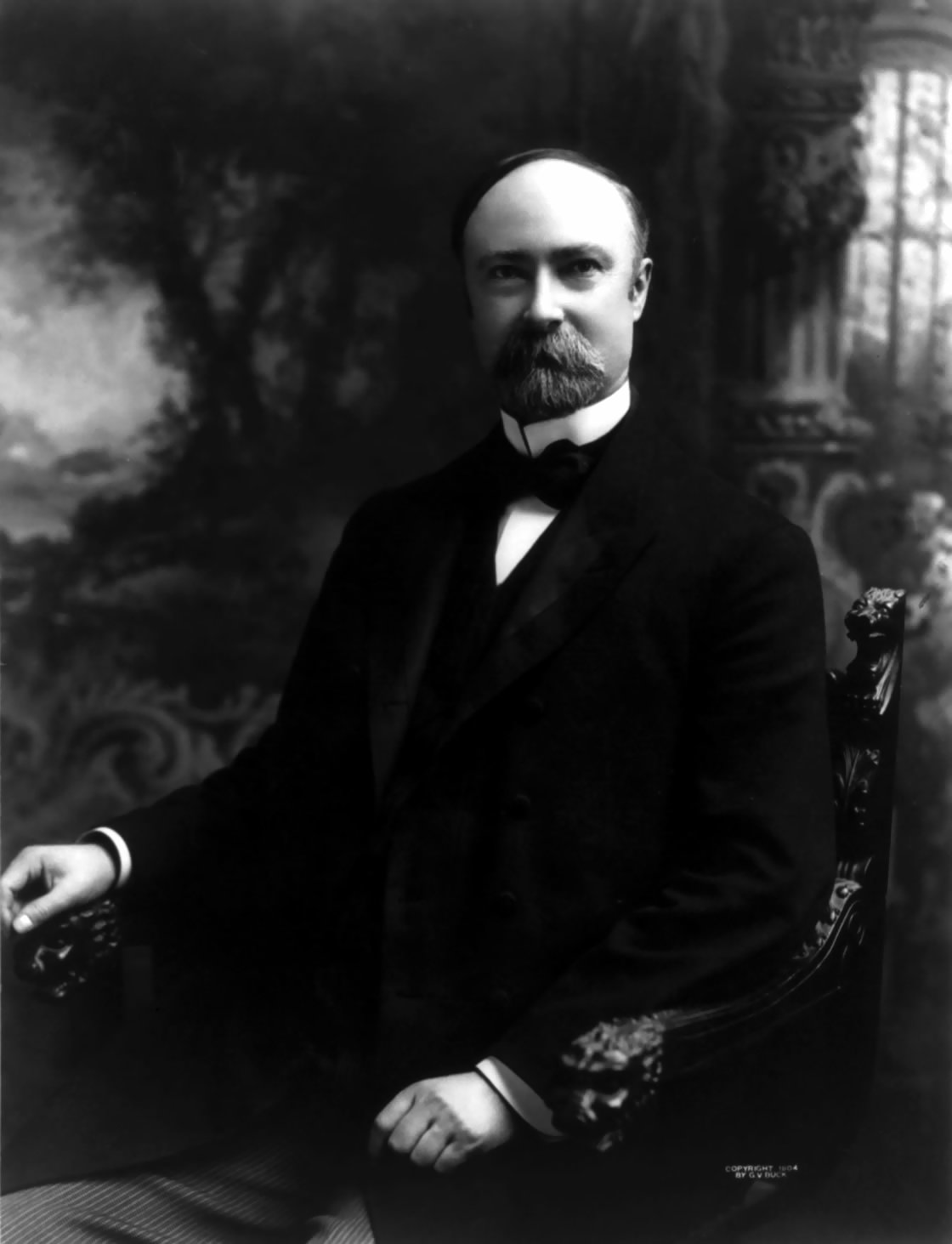

Charles Warren Fairbanks (May 11, 1852 – June 4, 1918) was an American politician who served as a

Fairbanks's first position was as an agent of the

Fairbanks's first position was as an agent of the  Prior to the

Prior to the

Fairbanks was elected vice president of the United States in 1904 on the Republican ticket with

Fairbanks was elected vice president of the United States in 1904 on the Republican ticket with

Fairbanks died of

Fairbanks died of

''The life and speeches of Hon. Charles Warren Fairbanks : Republican candidate for vice-president ''

* , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fairbanks, Charles W. 1852 births 1918 deaths 19th-century American politicians 20th-century vice presidents of the United States Candidates in the 1904 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1908 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1916 United States presidential election 1904 United States vice-presidential candidates 1916 United States vice-presidential candidates Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery Indiana lawyers Indiana Republicans Ohio lawyers Ohio Wesleyan University alumni People from Union County, Ohio Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Vice presidents of the United States Republican Party vice presidents of the United States Republican Party United States senators from Indiana Associated Press reporters Theodore Roosevelt administration cabinet members Fairbanks, Alaska

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

from Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

from 1897 to 1905 and the 26th vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

from 1905 to 1909. He was also the Republican vice presidential nominee in the 1916 presidential election. Had the Republican ticket been elected, Fairbanks would have become the third (and only non-consecutive) vice president to multiple presidents, after George Clinton and John C. Calhoun.

Born in Unionville Center, Ohio

Unionville Center is a village (United States)#Ohio, village in Union County, Ohio, Union County, Ohio, in the United States. The population was 233 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census.

The village is home to the Charles W. Fairbanks Fe ...

, Fairbanks moved to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

after graduating from Ohio Wesleyan University

Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) is a private liberal arts college in Delaware, Ohio. It was founded in 1842 by methodist leaders and Central Ohio residents as a nonsectarian institution, and is a member of the Ohio Five – a consortium ...

. He became an attorney and railroad financier, working under railroad magnate Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made hi ...

. Fairbanks delivered the keynote address at the 1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the firs ...

and won election to the Senate the following year. In the Senate, he became an advisor to President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and served on a commission that helped settle the Alaska boundary dispute

The Alaska boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which then controlled Canada's foreign relations. It was resolved by arbitration in 1903. The dispute had existed ...

.

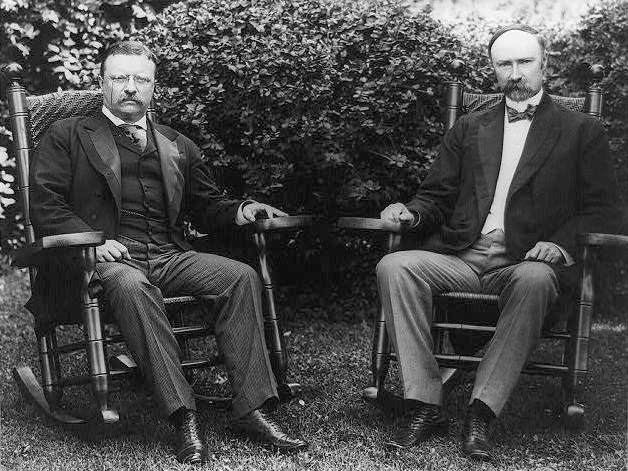

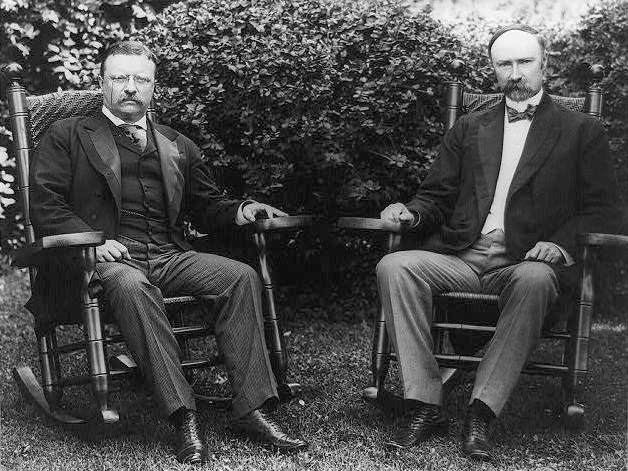

The 1904 Republican National Convention selected Fairbanks as the running mate for President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. As vice president, Fairbanks worked against Roosevelt's progressive policies. Fairbanks unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination at the 1908 Republican National Convention and backed William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

in 1912 against Roosevelt. Fairbanks sought the presidential nomination at the 1916 Republican National Convention, but was instead selected as the vice presidential nominee, with former Associate Justice and Governor Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, and would have been the third vice president to serve under different presidents (after George Clinton and John C. Calhoun), and the only one non-consecutively. The Hughes-Fairbanks ticket, however, narrowly lost to the Democratic ticket of President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and Vice President Thomas R. Marshall

Thomas Riley Marshall (March 14, 1854 – June 1, 1925) was an American politician who served as the 28th vice president of the United States from 1913 to 1921 under President Woodrow Wilson. A prominent lawyer in Indiana, he became an acti ...

.

Early life

Fairbanks was born in alog cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

near Unionville Center, Ohio

Unionville Center is a village (United States)#Ohio, village in Union County, Ohio, Union County, Ohio, in the United States. The population was 233 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census.

The village is home to the Charles W. Fairbanks Fe ...

, the son of Mary Adelaide (Smith) and Loriston Monroe Fairbanks, a wagon-maker. Fairbanks in his youth saw his family's home used as a hiding place for runaway slaves. After attending country schools and working on a farm, Fairbanks attended Ohio Wesleyan University

Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) is a private liberal arts college in Delaware, Ohio. It was founded in 1842 by methodist leaders and Central Ohio residents as a nonsectarian institution, and is a member of the Ohio Five – a consortium ...

, where he graduated in 1872. While there, Fairbanks was co-editor of the school newspaper with Cornelia Cole, whom he married after both graduated from the school.

Early career

Fairbanks's first position was as an agent of the

Fairbanks's first position was as an agent of the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, reporting on political rallies for Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

during the 1872 presidential election. He studied law in Pittsburgh before moving to Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, where he continued to work for the Associated Press while attending a semester at Cleveland Law School to complete his legal education. Fairbanks was admitted to the Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

bar in 1874, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Mari ...

. In 1875 he received his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree from Ohio Wesleyan.

During his early years in Indiana, Fairbanks was paid $5,000 a year as manager for the bankrupt Indianapolis, Bloomington, and Western Railroad. With the assistance of his uncle, Charles W. Smith, whose connections had helped him obtain the position, Fairbanks was able to become a railroad financier and served as counsel for millionaire Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made hi ...

.

Prior to the

Prior to the 1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Building in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana for preside ...

, federal judge Walter Q. Gresham

Walter Quintin Gresham (March 17, 1832May 28, 1895) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and of the United States Circuit Courts for the Seventh Circuit and previously was a United State ...

sought Fairbanks's help in campaigning for the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

nomination for U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. When Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

won the nomination, Fairbanks supported him and made campaign speeches on his behalf. Afterward, Fairbanks began to take an even greater interest in politics, and made campaign speeches on Harrison's behalf again in the campaign of 1892. In 1893, Fairbanks was a candidate for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, but Democrats controlled the state legislature and reelected incumbent Democrat David Turpie

David Battle Turpie (July 8, 1828 – April 21, 1909) was an American politician who served as a Senator from Indiana from 1887 until 1899; he also served as Chairman of the Senate Democratic Caucus from 1898 to 1899 during the last year of his ...

.

In 1894, Fairbanks was the most visible organizer and speaker on behalf of Republicans in elections for the state legislature. He was credited with delivering Republican majorities to both the Indiana House of Representatives

The Indiana House of Representatives is the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The House is composed of 100 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. House memb ...

and Indiana Senate

The Indiana Senate is the upper house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The Senate is composed of 50 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. Senators serve four-year terms ...

, ensuring that a Republican would be elected to succeed Daniel W. Voorhees in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

at the end of Voorhees's term in 1897. At the 1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the firs ...

, Fairbanks was both temporary chairman and keynote speaker, further raising his public profile. Fairbanks was the most likely Republican candidate for Voorhees's seat, and in January 1897 Republican legislators formally chose him as their nominee. On January 19, 1897, Fairbanks was elected to the Senate, and he took his seat on March 4.

Senator

During his eight years in the U.S. Senate, Fairbanks served as a key advisor to McKinley during theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

and was also the Chairman of the Committee on Immigration and the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds. In 1898, Fairbanks was appointed a member of the United States and British Joint High Commission which met in Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

for the adjustment of Canadian questions, including the Alaska boundary dispute

The Alaska boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which then controlled Canada's foreign relations. It was resolved by arbitration in 1903. The dispute had existed ...

.

Vice presidency (1905–1909)

Fairbanks was elected vice president of the United States in 1904 on the Republican ticket with

Fairbanks was elected vice president of the United States in 1904 on the Republican ticket with Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and served a four-year term, 1905 to 1909. He became the first vice president to serve a complete term without casting any tie-breaking votes as President of the Senate

President of the Senate is a title often given to the presiding officer of a senate. It corresponds to the speaker in some other assemblies.

The senate president often ranks high in a jurisdiction's succession for its top executive office: for e ...

. Fairbanks, a conservative whom Roosevelt had once labeled a "reactionary machine politician" (and who had been caricatured as a "Wall Street Puppet" during the campaign), actively worked against Roosevelt's progressive "Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

" program. Roosevelt did not give Fairbanks a significant role in his administration, and (having chosen not to seek reelection) strongly promoted William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

as his potential successor in 1908. Fairbanks also sought the Republican nomination for president, but was unsuccessful and returned to the practice of law. In 1912, Fairbanks supported Taft's reelection against Roosevelt's Bull Moose candidacy.

Post-vice presidency (1909–1918)

Hughes's running mate

In 1916, Fairbanks was in charge of establishing the platform for the Republican party. He sought that year's Republican presidential nomination at the party's June convention. WhenCharles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

was nominated, Fairbanks was selected by the convention as the vice presidential nominee, which would have returned him to office under a different president, a feat previously accomplished only by George Clinton and John C. Calhoun. In November, Hughes and Fairbanks lost a close election to the Democratic incumbents Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and Thomas Marshall. Fairbanks and 23rd Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

Adlai Stevenson share the distinction of seeking reelection to non-consecutive terms as vice president. Vice president Stevenson ran for a second non-consecutive term with William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

in the 1900 Election but he and Bryan lost to the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

ticket of William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. After the election, Fairbanks resumed the practice of law in Indianapolis, but his health soon started to fail.

Death and legacy

Fairbanks died of

Fairbanks died of nephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Types

* Glomerulonephritis is inflammation of th ...

in his home on June 4, 1918, at the age of 66, and he was interred in Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high poi ...

in Indianapolis.

Fairbanks received the honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

of LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1901, and from Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

in 1907. The Charles W. Fairbanks Professor of Politics and Government position at Ohio Wesleyan University is named for him.

The city of Fairbanks, Alaska

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

, and the Fairbanks North Star Borough

The Fairbanks North Star Borough is a borough located in the state of Alaska. As of the 2020 census, the population was 95,665, down from 97,581 in 2010.

The borough seat is Fairbanks. The borough's land area is slightly smaller than that o ...

within which it lies; the Fairbanks School District in Union County, Ohio

Union County is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 62,784. Its county seat is Marysville. Its name is reflective of its origins, it being the union of portions of Franklin, Delaware, Madis ...

; Fairbanks, Minnesota

Fairbanks is an unincorporated community in Fairbanks Township, Saint Louis County, Minnesota, United States; located within the Superior National Forest.

Geography

The community is 18 miles southeast of the city of Hoyt Lakes along Saint Lo ...

; Fairbanks, Oregon; and Fairbanks Township, Michigan

Fairbanks Township is a civil township of Delta County in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2010 census, the township population was 281, down from 321 at the 2000 census.

Communities

*Fayette is an unincorporated community on the easte ...

, are all named after him.

In 1966, the Indiana Sesquicentennial Commission placed an Indiana historical marker

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other ...

in front of Fairbanks's home at 30th and Meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

Streets in Indianapolis. On May 15, 2009, an Ohio historical marker was dedicated in Unionville Center, commemorating Fairbanks's birthplace.

See also

*List of vice presidents of the United States by time in office

This is a list of vice presidents of the United States by time in office. The basis of the list is the difference between ''dates''. The length of a full four-year term of office amounts to 1,461 days (three common years of 365 days plus one leap ...

References

External links

''The life and speeches of Hon. Charles Warren Fairbanks : Republican candidate for vice-president ''

* , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fairbanks, Charles W. 1852 births 1918 deaths 19th-century American politicians 20th-century vice presidents of the United States Candidates in the 1904 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1908 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1916 United States presidential election 1904 United States vice-presidential candidates 1916 United States vice-presidential candidates Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery Indiana lawyers Indiana Republicans Ohio lawyers Ohio Wesleyan University alumni People from Union County, Ohio Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Vice presidents of the United States Republican Party vice presidents of the United States Republican Party United States senators from Indiana Associated Press reporters Theodore Roosevelt administration cabinet members Fairbanks, Alaska