Charles Stewart (premier) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

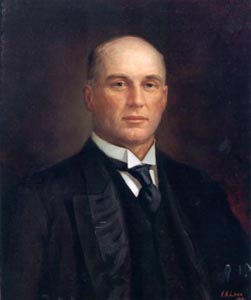

Charles Stewart, (August 26, 1868 – December 6, 1946) was a

In 1892, Charles Sr. died, leaving his son in charge of the family farm. In 1905, on July 8, this farm was destroyed by a tornado, and Stewart decided to move west, settling near

In 1892, Charles Sr. died, leaving his son in charge of the family farm. In 1905, on July 8, this farm was destroyed by a tornado, and Stewart decided to move west, settling near

Divisions within the provincial Liberals came to a head in August 1918, when Stewart dismissed Cross as Attorney-General. It later emerged that Cross had refused to fire two detectives in his department after Stewart had concluded that their work would be better done by the provincial police, and that Stewart had found Cross's work to be generally poor. He had asked for Cross's resignation, received no response, and rescinded the

Divisions within the provincial Liberals came to a head in August 1918, when Stewart dismissed Cross as Attorney-General. It later emerged that Cross had refused to fire two detectives in his department after Stewart had concluded that their work would be better done by the provincial police, and that Stewart had found Cross's work to be generally poor. He had asked for Cross's resignation, received no response, and rescinded the

Prohibition was not the only UFA-endorsed policy to have been passed by Sifton's government: indeed, the legislation that allowed for citizen-initiated referendums of the sort that had led to prohibition was itself the result of UFA advocacy. Once Stewart became Premier, he committed to the introduction of another UFA-favoured democratic reform—

Prohibition was not the only UFA-endorsed policy to have been passed by Sifton's government: indeed, the legislation that allowed for citizen-initiated referendums of the sort that had led to prohibition was itself the result of UFA advocacy. Once Stewart became Premier, he committed to the introduction of another UFA-favoured democratic reform—

Some in the UFA had long favoured contesting elections directly as a political party instead of remaining on the sidelines as a pressure group, but Wood and other UFA leaders were implacably opposed to the idea. During the war, however, the political wing began to gain momentum, and at the 1919 UFA convention, it was decided that UFA candidates would contest the next provincial election. In fact, it ended up doing so somewhat sooner: in 1919, Charles W. Fisher, Liberal MLA for

Some in the UFA had long favoured contesting elections directly as a political party instead of remaining on the sidelines as a pressure group, but Wood and other UFA leaders were implacably opposed to the idea. During the war, however, the political wing began to gain momentum, and at the 1919 UFA convention, it was decided that UFA candidates would contest the next provincial election. In fact, it ended up doing so somewhat sooner: in 1919, Charles W. Fisher, Liberal MLA for

In Jaques' view, Stewart was defined by what he was not:

In Jaques' view, Stewart was defined by what he was not:

As a cabinet minister, Stewart aggressively marketed Canada's coal both domestically and internationally, for which he was honoured by Alberta's coal producers at a banquet and later awarded the Randolph Bruce Gold Medal in Science by the

As a cabinet minister, Stewart aggressively marketed Canada's coal both domestically and internationally, for which he was honoured by Alberta's coal producers at a banquet and later awarded the Randolph Bruce Gold Medal in Science by the  Despite Stewart's involvement in transferring resource rights to Alberta, his relationship with the UFA government that had defeated him in 1921 was frosty: Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, in his biography of UFA Premier

Despite Stewart's involvement in transferring resource rights to Alberta, his relationship with the UFA government that had defeated him in 1921 was frosty: Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, in his biography of UFA Premier

Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

politician who served as the third premier of Alberta

The premier of Alberta is the first minister for the Canadian province of Alberta, and the province's head of government. The current premier is Danielle Smith, leader of the United Conservative Party, who was sworn in on October 11, 2022.

The ...

from 1917 until 1921. Born in Strabane, Ontario, in then Wentworth County (now part of Hamilton), Stewart was a farmer who moved west to Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

after his farm was destroyed by a storm. There he became active in politics and was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta

The Legislative Assembly of Alberta is the deliberative assembly of the province of Alberta, Canada. It sits in the Alberta Legislature Building in Edmonton. The Legislative Assembly currently has 87 members, elected first past the post from singl ...

in the 1909 election. He served as Minister of Public Works and Minister of Municipal Affairs—the first person to hold the latter position in Alberta—in the government of Arthur Sifton

Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton (October 26, 1858 – January 21, 1921) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and politician who served as the second premier of Alberta from 1910 until 1917. He became a minister in the federal cabinet of Canada thereaf ...

. When Sifton left provincial politics in 1917 to join the federal cabinet, Stewart was named his replacement.

As premier, Stewart tried to hold together his Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, which was divided by the Conscription Crisis of 1917

The Conscription Crisis of 1917 (french: Crise de la conscription de 1917) was a political and military crisis in Canada during World War I. It was mainly caused by disagreement on whether men should be conscripted to fight in the war, but also b ...

. He endeavoured to enforce prohibition of alcoholic beverages, which had been enshrined in law by a referendum during Sifton's premiership, but found that the law was not widely enough supported to be effectively policed. His government took over several of the province's financially troubled railroads, and guaranteed bonds sold to fund irrigation projects. Several of these policies were the result of lobbying by the United Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

(UFA), with which Stewart enjoyed good relations; even so, the UFA was politicized during Stewart's premiership and ran candidates in the 1921 election. Unable to match the UFA's appeal to rural voters, Stewart's government was defeated at the polls and he was succeeded as premier by Herbert Greenfield

Herbert W. Greenfield (November 25, 1869 – August 23, 1949) was a Canadian politician and farmer who served as the fourth premier of Alberta from 1921 until 1925. Born in Winchester, Hampshire, in England, he immigrated to Canada in his late tw ...

.

After leaving provincial politics, Stewart was invited to join the federal cabinet of William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

, in which he served as Minister of the Interior and Mines. In this capacity he signed, on behalf of the federal government, an agreement that transferred control of Alberta's natural resources from Ottawa to the provincial government—a concession he had been criticized for being unable to negotiate as Premier. He served in King's cabinet until 1930, when the King government was defeated, but remained a member of Parliament until he lost his seat in 1935. He died in December 1946 in Ottawa.

Early life

Charles Stewart was born on August 26, 1868, in Strabane, Ontario, on Wentworth County, to Charles and Catherine Stewart. Charles Sr. was astonemason

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, mo ...

and farmer. As a child, Charles Jr. accompanied his father to Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

to hear Canadian Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

. According to family lore, Macdonald noticed the young future Premier and told him that he was a fine boy who would make a good politician someday. When Charles Jr. was 16, he moved with his family to a farm near Barrie

Barrie is a city in Southern Ontario, Canada, about north of Toronto. The city is within Simcoe County and located along the shores of Kempenfelt Bay, the western arm of Lake Simcoe. Although physically in Simcoe County, Barrie is politically i ...

. Seven years later, on December 17, 1891, he married Jane Russell Sneath; the pair had eight children. After marrying Sneath, he converted to her Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

faith.

In 1892, Charles Sr. died, leaving his son in charge of the family farm. In 1905, on July 8, this farm was destroyed by a tornado, and Stewart decided to move west, settling near

In 1892, Charles Sr. died, leaving his son in charge of the family farm. In 1905, on July 8, this farm was destroyed by a tornado, and Stewart decided to move west, settling near Killam, Alberta

Killam is a town in central Alberta, Canada. It is located in Flagstaff County, east of Camrose at the junction of Highway 13 and Veterans Memorial Highway, Highway 36. Killam is located in a rich agricultural area and is a local hub for trade. ...

in 1906. His family endured a cold winter—the warmest place in their shack was on the kitchen table, so they kept the baby there—and in the spring their crops were destroyed by hail. As he was unsuccessful at farming, he supplemented his income using the stonemason's skills he had learned from his father: he laid foundations for the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

, worked on the High Level Bridge in Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city ancho ...

, and dug Killam's town well. He later worked in real estate and as a farm implement dealer, earning enough to buy a new and larger homestead in 1912.

Stewart was active in his local community: he was the first chair of the Killam School District, attended the first meeting of Killam ratepayers on January 19, 1907, and was involved in the incorporation of Killam in January 1908. In 1909, the Alberta Liberal Party

The Alberta Liberal Party (french: Parti libéral de l'Alberta) is a provincial political party in Alberta, Canada. Founded in 1905, it is the oldest active political party in Alberta and was the dominant political party until the 1921 election ...

, which had dominated provincial politics throughout Alberta's short history, came seeking a candidate to run in the new riding of Sedgewick. Stewart agreed to run and was elected by acclamation

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

in the 1909 election.

Early political career

At the time of Stewart's acclamation, PremierAlexander Cameron Rutherford

Alexander Cameron Rutherford (February 2, 1857 – June 11, 1941) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the first premier of Alberta from 1905 to 1910. Born in Ormond, Canada West, he studied and practiced law in Ottawa before h ...

seemed unassailable: he controlled 36 of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta

The Legislative Assembly of Alberta is the deliberative assembly of the province of Alberta, Canada. It sits in the Alberta Legislature Building in Edmonton. The Legislative Assembly currently has 87 members, elected first past the post from singl ...

's 41 seats (Stewart's being one), and his Liberals had just won nearly sixty percent of the vote in their re-election bid. Months later, however, Rutherford and his government were embroiled in the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway scandal

The Alberta and Great Waterways Railway Scandal was a political scandal in Alberta, Canada in 1910, which forced the resignation of Liberal premier Alexander Cameron Rutherford. Rutherford and his government were accused of giving loan guarant ...

, and the Liberal Party was split. Initially, Stewart remained loyal to Rutherford, and went so far as to allege in the legislature that insurgent Liberal John R. Boyle

John Robert Boyle, (February 1, 1870 or February 3, 1871 – February 15, 1936) was a Canadian politician and jurist who served as a Member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta, a cabinet minister in the Government of Alberta, and a judge on ...

had offered two members of the legislative assembly (MLAs), who were also hotel keepers, immunity from prosecution for liquor violations if they would support a new government in which Boyle was Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

. As additional details of the scandal emerged, however, Stewart himself became an insurgent, and was pleased when Arthur Sifton

Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton (October 26, 1858 – January 21, 1921) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and politician who served as the second premier of Alberta from 1910 until 1917. He became a minister in the federal cabinet of Canada thereaf ...

replaced Rutherford as Premier.

In May 1912, Sifton expanded his cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, and Stewart was made the province's first Minister of Municipal Affairs. As was required by the custom of the day when an MLA was appointed to cabinet, he resigned his seat to run in a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

, in which he easily defeated Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

William John Blair

William John Blair (October 13, 1875 – April 24, 1943) was a Canadian engineer, farmer, teacher, soldier surveyor and federal politician from Alberta.

Early life

William John Blair was born in Embro, Ontario on October 13, 1875 to John Blai ...

. In cabinet, he became known as an advocate of public ownership of utilities, which placed him more in sympathy with the Conservative opposition than with Sifton. Despite this position, he backed Sifton's 1913 resolution to the Alberta and Great Waterways problem, which involved partnering with the private sector; this vote marked the first time that the Liberal caucus was united on the railways question since before the scandal broke in 1910.

In December 1913, Sifton moved Stewart from Municipal Affairs into the Public Works portfolio; in this capacity, Stewart played a major role in the incorporation of the Alberta Farmers' Co-operative Elevator Company

The Alberta Farmers' Co-operative Elevator Company (AFCEC) was a farmer-owned enterprise that provided grain storage and handling services to farmers in Alberta, Canada between 1913 and 1917, when it was merged with the Manitoba-based Grain Grower ...

, which was a farmer-run co-operative with a charter to own and operate grain elevator

A grain elevator is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lower level and deposits ...

s.

Premier

Shortly after the 1917 provincial election (in which Stewart and the Liberals were both soundly re-elected), Canada found itself embroiled in a conscription crisis. The federalConservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

government, led by Robert Borden

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Canada from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I.

Borde ...

, supported implementing conscription. The opposition Liberals, led by Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier, ( ; ; November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadian prime minis ...

, nominally opposed conscription, but many English-speaking Liberals in fact supported it. The crisis was resolved when Borden formed a Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

government composed of Conservatives and pro-conscription Liberals. Sifton, falling into the latter group, was chosen as Alberta's representative in that government, and resigned as Premier in October 1917. Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

Robert Brett

Robert George Brett (November 16, 1851 – September 16, 1929) was a politician and physician in the North-West Territories and Alberta, Canada and served as the second Lieutenant Governor of Alberta.

Early life

Robert George Brett was born on ...

, accepting Sifton's choice of successor, asked Stewart to form a government. His only serious rival for the position of premier was Charles Wilson Cross

Charles Wilson Cross (November 30, 1872 – June 2, 1928) was a Canadian politician who served in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta and the House of Commons of Canada. He was also the first Attorney-General of Alberta. Born in Ontario, he s ...

, who opposed conscription and was therefore not a palatable choice for much of the Liberal establishment.

Party division

The Alberta and Great Waterways scandal had opened up a rift in the provincial Liberal Party, between those who remained loyal to Cross and Rutherford and those who did not, with the latter group being led byWilliam Henry Cushing

William Henry Cushing (August 21, 1852 – January 25, 1934) was a Canadian politician. Born in Ontario, he migrated west as a young adult where he started a successful lumber company and later became Alberta's first Minister of Public Works and ...

and Frank Oliver. Sifton had papered over, if not in fact healed, this rift, and it did not burst open again until the conscription crisis. This time, however, the fault lines were different: Cross and Oliver had put aside their longtime enmity to join in opposing conscription, and Sifton, who had been selected Premier in part because he was not identified with either faction in the old feud, was Alberta's most prominent pro-conscription Liberal.

Stewart was a supporter of conscription and of the Union government, but did not take any active part in the acrimonious 1917 federal election, which was fought on the issue. Several of his ministers were not so circumspect: Attorney-General Cross, Education Minister Boyle, and Municipal Affairs Minister Wilfrid Gariépy

Wilfrid Gariepy (March 14, 1877 – January 13, 1960) was a Canadian politician, member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta and provincial cabinet minister, member of the House of Commons of Canada, and municipal councillor in Edmonton.

Early ...

campaigned for the Laurier Liberals

Prior to the 1917 federal election in Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada split into two factions. To differentiate the groups, historians tend to use two retrospective names:

* The Laurier Liberals, who opposed conscription of soldiers to supp ...

; Public Works Minister Archibald J. McLean

Archibald James McLean (September 25, 1860 – October 13, 1933) was a Ranch, cattleman and politician from Ontario, Ontario, Canada. He was one of the The Big Four (Calgary), Big Four who helped found the Calgary Stampede in 1912.

Biography ...

and Treasurer Charles R. Mitchell

Charles Richmond Mitchell (November 30, 1872 – August 16, 1942) was a Canadian lawyer, judge, cabinet minister and former Leader of the Official Opposition in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta.

Early life

Mitchell was born in Newcastle, Ne ...

stayed out of the fray while leaving no doubt of their support for Union. During the first legislative session after this election, Stewart came under attack from members of his own party. Alexander Grant MacKay

Alexander Grant MacKay (March 7, 1860 – April 25, 1920) was a Canadian teacher, lawyer and provincial level politician. He served prominent posts in two provincial legislatures as Leader of the Opposition in Ontario and as a Cabinet Ministe ...

criticized his failure to take advantage of the recent conference of premiers to press for the transfer of rights over Alberta's natural resources from the federal to the provincial government (Sifton had made this a priority during the pre-war years, but had largely ceased his advocacy on the breakout of hostilities), and James Gray Turgeon

James Gray Turgeon (October 7, 1879 – February 14, 1964) was a broker, soldier, and provincial and federal level politician from Canada. He served as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta from 1913 to 1921 sitting with the Alberta Li ...

attacked the government's policy of levying taxes for the support of soldiers' dependants on the grounds that he considered it a federal responsibility.

Divisions within the provincial Liberals came to a head in August 1918, when Stewart dismissed Cross as Attorney-General. It later emerged that Cross had refused to fire two detectives in his department after Stewart had concluded that their work would be better done by the provincial police, and that Stewart had found Cross's work to be generally poor. He had asked for Cross's resignation, received no response, and rescinded the

Divisions within the provincial Liberals came to a head in August 1918, when Stewart dismissed Cross as Attorney-General. It later emerged that Cross had refused to fire two detectives in his department after Stewart had concluded that their work would be better done by the provincial police, and that Stewart had found Cross's work to be generally poor. He had asked for Cross's resignation, received no response, and rescinded the Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' Ki ...

appointing him. In an effort to secure Cross's departure from politics, Stewart offered him the position of Alberta's provincial agent in London, England

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

; Cross refused it, and Stewart was criticized for using appointments for political advantage.

Prohibition and democratic reform

Alberta had implementedprohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

in 1916 as the result of a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

supported by the powerful United Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

(UFA) lobby group. By the time Stewart took office, it was becoming apparent that the policy was not being universally complied with: Conservative MLA George Douglas Stanley

George Douglas Stanley (March 19, 1876 – February 22, 1954) was a politician and physician from Alberta, Canada. He began as a pioneer medical doctor in Alberta in 1901. He served in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta from 1913 to 1921 as a ...

alleged that judges were often hungover when they sat in judgment of those accused of violating liquor laws, and Cross's replacement as Attorney-General, John Boyle, admitted that in his estimation 65% of the province's male population broke the Prohibition Act. In 1921 the government realized profits of $800,000 on alcohol legally sold for "medicinal" purposes, and Boyle estimated bootleggers

Bootleg or bootlegging most often refers to:

* Bootleg recording, an audio or video recording released unofficially

* Rum-running, the illegal business of transporting and trading in alcoholic beverages, hence:

** Moonshine, or illicitly made ...

' profits at nine times that figure. Stewart blamed the problems on insufficient public support for the law, but even as he did so it was clear that there was not enough support to repeal it.

Prohibition was not the only UFA-endorsed policy to have been passed by Sifton's government: indeed, the legislation that allowed for citizen-initiated referendums of the sort that had led to prohibition was itself the result of UFA advocacy. Once Stewart became Premier, he committed to the introduction of another UFA-favoured democratic reform—

Prohibition was not the only UFA-endorsed policy to have been passed by Sifton's government: indeed, the legislation that allowed for citizen-initiated referendums of the sort that had led to prohibition was itself the result of UFA advocacy. Once Stewart became Premier, he committed to the introduction of another UFA-favoured democratic reform—proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

. However, a committee formed to examine the possibility disintegrated over what historian Carrol Jaques calls "battles within the group and a general dislike of the concept".

Public works

Railway development had dominated the premierships of Stewart's predecessors and, while losing political potency as an issue, it was still a matter that demanded his attention. Though Sifton had established a railway policy in 1913 that was satisfactory to all wings of the Liberal Party, the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

the following year had all but put an end to railway construction across Canada. Once peace came, Albertans living near promised but as yet unbuilt lines began to clamour for their completion. The private companies with whom the government had partnered, however, were in no position to undertake the construction. The Edmonton, Dunvegan and British Columbia Railway was taken over by the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

, with a clause in the agreement requiring the provincial government to spend $1 million to improve the route, and the Alberta and Great Waterways was taken over by Stewart's government directly (J. D. McArthur, the line's previous owner, retained an option to repurchase it, but it was never exercised).

Irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

projects also occupied much of Stewart's attention as Premier. As with railways, the First World War had disrupted planned irrigation projects, and Albertan farmers, especially those from the arid south

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

, were eager to see them resumed. Specifically popular was a project to irrigate in Lethbridge County

Lethbridge County is a municipal district in southern Alberta, Canada. It is in Census Division No. 2 and part of the Lethbridge census agglomeration. It was known as the ''County of Lethbridge'' prior to December 4, 2013. Its name was change ...

, but when bonds were issued to finance the project, they did not sell. Stewart sought federal backing of the bonds, but Prime Minister Arthur Meighen

Arthur Meighen (; June 16, 1874 – August 5, 1960) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Canada from 1920 to 1921 and from June to September 1926. He led the Conservative Party from 1920 to 1926 and fro ...

declined. Stewart reluctantly agreed to offer a provincial guarantee, but to avoid negative reaction from northern Alberta

Northern Alberta is a geographic region located in the Canadian province of Alberta.

An informally defined cultural region, the boundaries of Northern Alberta are not fixed. Under some schemes, the region encompasses everything north of the cent ...

he linked the enabling legislation to one allowing for drainage

Drainage is the natural or artificial removal of a surface's water and sub-surface water from an area with excess of water. The internal drainage of most agricultural soils is good enough to prevent severe waterlogging (anaerobic conditio ...

in northern areas.

Stewart and the United Farmers of Alberta

TheUnited Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

had its beginnings as a farmers' advocacy organization; Stewart, a farmer, had joined it. The UFA had achieved several successes in dealing with the Sifton government, and Stewart also endeavoured to cooperate with it. The irrigation project was strongly supported by the UFA, as was Stewart's action on proportional representation. When Peace River

The Peace River (french: links=no, rivière de la Paix) is a river in Canada that originates in the Rocky Mountains of northern British Columbia and flows to the northeast through northern Alberta. The Peace River joins the Athabasca River in th ...

MLA William Archibald Rae

William Archibald Rae (May 3, 1875 – May 5, 1943) was a businessman and provincial level politician from Alberta, Canada. He was born in Thedford, Ontario.

Argonaut Company

Rae was instrumental in the founding of Grande Prairie, Alberta with ...

introduced legislation to allow Imperial Oil

Imperial Oil Limited (French: ''Compagnie Pétrolière Impériale Ltée'') is a Canadian petroleum company. It is Canada's second-biggest integrated oil company. It is majority owned by American oil company ExxonMobil with around 69.6 percent ...

to build a pipeline

Pipeline may refer to:

Electronics, computers and computing

* Pipeline (computing), a chain of data-processing stages or a CPU optimization found on

** Instruction pipelining, a technique for implementing instruction-level parallelism within a s ...

in the province, UFA President Henry Wise Wood sent Stewart a telegram of protest, as he believed that pipelines should be common carrier

A common carrier in common law countries (corresponding to a public carrier in some civil law systems,Encyclopædia Britannica CD 2000 "Civil-law public carrier" from "carriage of goods" usually called simply a ''carrier'') is a person or compan ...

s; Stewart read it in the legislature, and Rae's bill was withdrawn. Even given the victories, the UFA was not satisfied with the government's record: in 1918, the government took action on only three of the many resolutions the UFA had sent to it.

Some in the UFA had long favoured contesting elections directly as a political party instead of remaining on the sidelines as a pressure group, but Wood and other UFA leaders were implacably opposed to the idea. During the war, however, the political wing began to gain momentum, and at the 1919 UFA convention, it was decided that UFA candidates would contest the next provincial election. In fact, it ended up doing so somewhat sooner: in 1919, Charles W. Fisher, Liberal MLA for

Some in the UFA had long favoured contesting elections directly as a political party instead of remaining on the sidelines as a pressure group, but Wood and other UFA leaders were implacably opposed to the idea. During the war, however, the political wing began to gain momentum, and at the 1919 UFA convention, it was decided that UFA candidates would contest the next provincial election. In fact, it ended up doing so somewhat sooner: in 1919, Charles W. Fisher, Liberal MLA for Cochrane Cochrane may refer to:

Places Australia

*Cochrane railway station, Sydney, a railway station on the closed Ropes Creek railway line

Canada

* Cochrane, Alberta

* Cochrane Lake, Alberta

* Cochrane District, Ontario

** Cochrane, Ontario, a town wit ...

, died as a result of that year's influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

epidemic, and a by-election was necessitated to replace him. The UFA's Alex Moore defeated his only opponent, Liberal Edward V. Thomson, by 835 votes to 708.

Stewart felt betrayed: "It has been my fight ever since I became a minister to see that the farmers of the province were having a square deal," he remarked, "and I think I have done this with some success." Despite his general sympathy with the aims of the UFA, he could not support their transition into a political party. For one, he disagreed with the UFA's belief that politics should be conducted along class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

, rather than ideological, lines. Stewart believed that "the more strongly armed the classes become the harder will it be to get the things we really need in our government" and asserted that "I never did and never will have any desire to form a coalition with anybody except with men who think the same as I do."

Given the UFA's formal adoption of the goal of replacing Stewart's Liberal government with a Farmer government, it remained surprisingly friendly towards the Premier. While campaigning for Moore during the Cochrane by-election, Wood called Stewart "an honourable, upright citizen, doing the best he could under difficult circumstances" and boasted that "if I have got to tear down the character of an honourable man to build up something that I want, I am not going to build it up." When at last the general election came, in 1921, the UFA declined to run a candidate in Stewart's Sedgewick riding as a sign of respect to the Premier. After the UFA swept to victory, there was even speculation that Stewart, still a UFA member, would stay on as Premier of a new Farmer's government (as part of its opposition to "old style politics," the UFA had contested the election without designating a leader), but he announced otherwise.

Defeat and legacy

The last provincial election had been held in June 1917, and four years was the normal life of a legislature in Canada. Stewart called an election for July 19. Though the Liberals' fortunes had been sagging in the post-war years, there remained no doubt that they could again defeat the Conservatives; their real challenge was evidently from the newly politicized UFA. Bolstering this challenge by increasing farmers' discontent was a collapse of agricultural prices. The UFA had no leader, no fixed platform, and no inclination to attack Stewart or his government. What it did have was superior organization, and on election day this organization made itself felt in the form of thirty-nine UFA members elected to fourteen Liberals. Stewart, who has been acclaimed in his own riding of Sedgewick, announced that he would resign as Premier as soon as the UFA had selected somebody to replace him. Once it selectedHerbert Greenfield

Herbert W. Greenfield (November 25, 1869 – August 23, 1949) was a Canadian politician and farmer who served as the fourth premier of Alberta from 1921 until 1925. Born in Winchester, Hampshire, in England, he immigrated to Canada in his late tw ...

, Stewart made good on his pledge, and Greenfield replaced him August 13.

In Jaques' view, Stewart was defined by what he was not:

In Jaques' view, Stewart was defined by what he was not: he was not involved in any of the railway scandals, current or past; he was not conspicuously involved in any of the personal battles that had consumed Alexander Rutherford, Frank Oliver, the brothers Arthur and Clifford Sifton, Charles Cross, or any of their followers; he was not a high-powered flamboyant Liberal partisan; he did not let himself get involved in federal Liberal Party machinations over issues such as the conscription crisis; nor did he seem to be high-handed or dictatorial—a criticism levelled at his predecessor, Arthur Sifton.She argues that he was a "decent family man" whose career was a product of the circumstances in which he found himself. Historian L. G. Thomas recognized Stewart's admirable qualities, but criticized him for lacking Sifton's "ruthless and forceful leadership" and claimed that "few provincial premiers have been more universally praised by their opponents and more unanimously deplored by their supporters." Even so, he acknowledged that the decisive factor in Stewart's downfall was not anything that he did, but the decision by the UFA to run candidates in 1921; in Thomas's view, Sifton would have been defeated in 1917 if he had had to contend with a politicized UFA. Mount Charles Stewart is located in the Bow Valley just north of Canmore. The peak was named for him in 1928.

Federal politics

Following the 1921 federal election,William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

's Liberals came to power in Ottawa. They had not won any seats in Alberta, and Stewart was invited to join King's cabinet as Minister of the Interior and Mines (which included responsibility as Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs). He won a 1922 by-election in the Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

seat of Argenteuil

Argenteuil () is a Communes of France, commune in the northwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, center of Paris. Argenteuil is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Val-d'Oise Departments of France, ...

, before shifting to the more familiar territory of Edmonton West

Edmonton West (french: Edmonton-Ouest) is a federal electoral district in Alberta, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1917 to 1988, from 1997 to 2004 and again since 2015.

Demographics

History and geography

T ...

in the 1925 election; he was re-elected there in 1926

Events January

* January 3 – Theodoros Pangalos declares himself dictator in Greece.

* January 8

**Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud is crowned King of Hejaz.

** Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Thuy ascends the throne, the last monarch of V ...

and 1930

Events

January

* January 15 – The Moon moves into its nearest point to Earth, called perigee, at the same time as its fullest phase of the Lunar Cycle. This is the closest moon distance at in recent history, and the next one will be ...

. In the 1935 election, he ran in the new riding of Jasper—Edson

Jasper—Edson was a federal electoral district in Alberta, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1935 to 1968.

This riding was created in 1933 from parts of Peace River riding. The electoral district was abolish ...

, where he was defeated by Social Crediter Walter Frederick Kuhl

Walter Frederick Kuhl (June 25, 1905 – January 11, 1991) was a teacher and a Canadian federal politician.

Born in Spruce Grove, Alberta, Kuhl was elected under the Social Credit banner to the House of Commons of Canada in the 1935 Canad ...

.

As a cabinet minister, Stewart aggressively marketed Canada's coal both domestically and internationally, for which he was honoured by Alberta's coal producers at a banquet and later awarded the Randolph Bruce Gold Medal in Science by the

As a cabinet minister, Stewart aggressively marketed Canada's coal both domestically and internationally, for which he was honoured by Alberta's coal producers at a banquet and later awarded the Randolph Bruce Gold Medal in Science by the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

The Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum (CIM) is a not-for-profit technical society of professionals in the Canadian minerals, metals, materials and energy industries. CIM's members are convened from industry, academia and go ...

. He took a great interest in water power

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of a wa ...

, and advised the government on jurisdictional issues surrounding the Niagara

Niagara may refer to:

Geography Niagara Falls and nearby places In both the United States and Canada

*Niagara Falls, the famous waterfalls in the Niagara River

*Niagara River, part of the U.S.–Canada border

*Niagara Escarpment, the cliff ov ...

, St. Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, and Milk Rivers. In 1927, he served as Canada's representative at the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. As Minister of the Interior, he oversaw the 1927 creation of Prince Albert National Park

Prince Albert National Park encompasses in central Saskatchewan, Canada and is located north of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Saskatoon. Though declared a National parks of Canada, national park March 24, 1927, official opening ceremonies weren't ...

. Ironically, given the attacks he had sustained as Premier from Alexander Grant MacKay, he was part of the federal delegation that finally negotiated the transfer of resource control from the federal to the Alberta provincial government in December 1929. The same agreement transferred resource rights to Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

and Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

. After it was signed but before it took effect, Manitoba Premier John Bracken

John Bracken (June 22, 1883 – March 18, 1969) was a Canadian agronomist and politician who was the 11th and longest-serving premier of Manitoba (1922–1943) and later the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada (1942–19 ...

concluded an agreement with the Winnipeg Electric Company, a private concern, to develop a hydroelectric dam

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

at Seven Sisters' Reach. Because resource rights were still controlled by the federal government, the deal required federal approval. Stewart advocated withholding this approval in deference to Manitoba public opinion, which favoured public ownership of such projects, but King honoured a provision of the resource transfer agreement that required the wishes of provincial governments to be respected until the transfer was complete and granted approval. Stewart's preference for public over private ownership extended to King's planned creation of the Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada (BoC; french: Banque du Canada) is a Crown corporation and Canada's central bank. Chartered in 1934 under the ''Bank of Canada Act'', it is responsible for formulating Canada's monetary policy,OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Ca ...

; Stewart wanted the new institution entirely under the control of the government, but King preferred an arrangement whereby half of its directors would be appointed by the government and half by private shareholders and suggested that advocates of public ownership might find themselves more at home in the socialist Cooperative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF; french: Fédération du Commonwealth Coopératif, FCC); from 1955 the Social Democratic Party of Canada (''french: Parti social démocratique du Canada''), was a federal democratic socialistThe follo ...

than in his Liberal caucus.

Despite Stewart's involvement in transferring resource rights to Alberta, his relationship with the UFA government that had defeated him in 1921 was frosty: Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, in his biography of UFA Premier

Despite Stewart's involvement in transferring resource rights to Alberta, his relationship with the UFA government that had defeated him in 1921 was frosty: Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, in his biography of UFA Premier John Edward Brownlee

John Edward Brownlee, (August 27, 1883 – July 15, 1961) was the fifth premier of Alberta, serving from 1925 until 1934. Born in Port Ryerse, Ontario, he studied history and political science at the University of Toronto's Victoria College ...

, alleges that this antipathy influenced Stewart's preference for private corporations over the Alberta government in granting hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

permits. He also feuded with then-Premier Brownlee over development in Alberta's national parks

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

(Stewart favouring large-scale private development and Brownlee opposing it), causing King to record in his diary "Brownlee strikes me as...being superior to Mr. Stewart, who is handicapped in his dislike of rownlee" When King sought to absorb Progressives

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techno ...

into his Liberal Party to form a stronger coalition against the Conservatives, Stewart opposed cooperation with the UFA leaders who made up a large part of the Progressives' Albertan base. While King was inclined to view UFA politicians, like Progressives elsewhere, as "Liberals in a hurry" who were fundamentally comfortable with his government and preferred it to the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, Stewart understood that the UFA was a distinct group whose members were in many respect more conservative than liberal. King dismissed his minister's views as being the result of Stewart's acrimonious history with the UFA.

In fact, Stewart did not enjoy King's confidence. Though he brought him into his cabinet in 1921 in part at the urging of Progressive leader Thomas Crerar

Thomas Alexander Crerar, (June 17, 1876 – April 11, 1975) was a western Canadian politician and a leader of the short-lived Progressive Party of Canada. He was born in Molesworth, Ontario, and moved to Manitoba at a young age.

Early career ...

, King found Stewart to be an inadequate protector of western interests—especially in his advocacy of tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

reduction, which King found lacklustre—and did not trust his political advice on the west. By 1925 he was considering appointing Stewart to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, to remove him from active political involvement, but was handicapped by the absence of any other Alberta representation in his cabinet. In 1926 Stewart served as an emissary from King to recruit Saskatchewan Premier Charles Avery Dunning

Charles Avery Dunning (July 31, 1885 – October 1, 1958) was the third premier of Saskatchewan. Born in England, he emigrated to Canada at the age of 16. By the age of 36, he was premier. He had a successful career as a farmer, business ...

to the federal cabinet; the mission fulfilled, King kept Stewart in cabinet but wrote in his diary that all matters pertaining to Alberta were to be "left to Dunning to do as he thinks best". By 1927, King complained that Stewart had "no grip" on the province of which he had once been Premier, and in 1930 he wrote "Organization in Alberta is terrible. Stewart is worse than useless, is like an old woman, with no real control of situation." In the 1930 federal election Dunning and Crerar were both defeated; King complained that it was "perfectly terrible to have Stewart alone representing the West." When Stewart too went down to defeat in 1935, King was pleased "not to have to consider him" in assembling his new cabinet, and opted instead to leave Alberta unrepresented to punish it for failing to elect any Liberals.

Post-political life

After Stewart's defeat in 1935, he was appointed byGeorge V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

to chair the Canadian section of the International Joint Commission

The International Joint Commission (french: Commission mixte internationale) is a bi-national organization established by the governments of the United States and Canada under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. Its responsibilities were expa ...

, in recognition of his expertise on international water boundary issues. In 1938, he was appointed chair of the Canadian section of the British Columbia – Yukon – Alaska Highway Commission. In these capacities, he travelled across Canada, visiting his son George at the family homestead near Killam at every opportunity. He died December 6, 1946, leaving an estate of $21,961.

Born in one of Canada's original provinces, Stewart moved west as part of a vast migration to the prairies, and settled in Alberta the year it became a province. As Alberta grew, Stewart played an increasingly important political role in it, until he joined the federal government to become Alberta's voice there, ultimately helping it achieve constitutional equality with the older provinces by transferring to its government control of its resources. As Mackenzie King eulogized him, "in more respects than one, Mr. Stewart's career mirrored the development of Canada itself."

Electoral record

As party leader

As MLA

As MP

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stewart, Charles 1868 births 1946 deaths Alberta Liberal Party MLAs Canadian Anglicans Leaders of the Alberta Liberal Party Liberal Party of Canada MPs Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Alberta Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Farmers from Ontario People from Flagstaff County Premiers of Alberta Interior ministers of Canada Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa)