Charles Curtis (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Curtis (January 25, 1860 – February 8, 1936) was an American attorney and

Curtis resigned from the House after he had been elected by the

Curtis resigned from the House after he had been elected by the

File:Hot weather cabinet, Vice President Curtis LCCN2002712156 (cropped).tif, Vice President Curtis during the summer of 1929

File:The Vice President makes ready for extra session. Vice President Curtis, standing in the ? of the Senate Chamber ready to open the extra session of the 71st Congress. Many important issues LCCN2016889265.tif, Vice President Curtis, standing in the Senate Chamber, 1929

File:Vice President Curtis receives peace pipe from Chief Red Tomahawk, slayer of Sitting Bull. Chief Red Tomahawk, leader of the Sioux Nation and credited with having killed Sitting Bull, LCCN2016889332.jpg, Vice President Curtis receives a

Curtis decided to stay in

Curtis decided to stay in

Unfinished autobiography

edited by Kitty Frank and confirmed by the Kansas State Historical Society *

"Charles Curtis; Native-American Indian Vice-President; a biography"

, Vice President Charles Curtis Website

Moro Films official movie web site

Don C. Seitz, ''From Kaw Teepee to Capitol; The Life Story of Charles Curtis, Indian, Who Has Risen to High Estate''

full text, Hathi Trust Digital Library

Charles Curtis House Museum

, official website *

by Deb Goodrich

Image of Vice-President Charles Curtis at a banquet on-board a military ship, Los Angeles (?), 1932.

''

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

politician from Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

who served as the 31st vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

from 1929 to 1933 under Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

. He had served as the Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding t ...

from 1924 to 1929. A member of the Kaw Nation

The Kaw Nation (or Kanza or Kansa) is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma and parts of Kansas. It comes from the central Midwestern United States. It has also been called the "People of the South wind",

born in the Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

, Curtis was the first Native American and first person with acknowledged non-European ancestry to reach either of the highest offices in the federal executive branch.

Based on his personal experience, Curtis believed that Indians could benefit from mainstream education and assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

. He entered political life when he was 32 years old and won several terms from his district in Topeka, Kansas

Topeka ( ; Kansa language, Kansa: ; iow, Dópikˀe, script=Latn or ) is the Capital (political), capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the County seat, seat of Shawnee County, Kansas, Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the ...

, beginning in 1892 as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. There, he sponsored and helped pass the Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act; it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw ...

, which extended the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pre ...

to the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

of Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

. Implementation of the Act completed the ending of tribal land titles in Indian Territory and prepared the larger territory to be admitted as the State of Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New M ...

, which occurred in 1907. The government tried to encourage Indians to accept individual citizenship and lands and to take up European-American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

culture.

Curtis was elected to the U.S. Senate first by the Kansas Legislature

The Kansas Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kansas. It is a bicameral assembly, composed of the lower Kansas House of Representatives, with 125 state representatives, and the upper Kansas Senate, with 40 state senators. ...

in 1906 and then by popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

in 1914

This year saw the beginning of what became known as World War I, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It als ...

, 1920

Events January

* January 1

** Polish–Soviet War in 1920: The Russian Red Army increases its troops along the Polish border from 4 divisions to 20.

** Kauniainen, completely surrounded by the city of Espoo, secedes from Espoo as its own ma ...

, and 1926

Events January

* January 3 – Theodoros Pangalos declares himself dictator in Greece.

* January 8

**Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud is crowned King of Hejaz.

** Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Thuy ascends the throne, the last monarch of V ...

. Curtis served one six-year term from 1907 to 1913 and then most of three terms from 1915 to 1929, when he was elected as vice-president. His long popularity and connections in Kansas and federal politics helped make Curtis a strong leader in the Senate. He marshaled support to be elected as Republican Whip

Party leaders of the United States House of Representatives, also known as floor leaders, are congresspeople who coordinate legislative initiatives and serve as the chief spokespersons for their parties on the House floor. These leaders are ele ...

from 1915 to 1924 and then as Senate Majority Leader from 1924 to 1929. In those positions, he was instrumental in managing legislation and in accomplishing Republican national goals.

Curtis ran for vice president alongside Herbert Hoover for president in 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhanov, J ...

—winning a landslide victory. In 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

, he became the first United States vice president to have ever opened the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

. However, when Curtis and Hoover ran together again in 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, they lost as the public gave the Democrats Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and John Nance Garner

John Nance Garner III (November 22, 1868 – November 7, 1967), known among his contemporaries as "Cactus Jack", was an American History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician and lawyer from History of Texas, Texas who ...

a landslide victory that year. Curtis remains the highest-ranking enrolled Native American who ever served in the federal government. He is also the most recent officer of the executive branch to have been born in a territory, rather than a state or federal district. He remained the only mixed-race vice president in American history until the inauguration of Kamala Harris

Kamala Devi Harris ( ; born October 20, 1964) is an American politician and attorney who is the 49th vice president of the United States. She is the first female vice president and the highest-ranking female official in U.S. history, as well ...

in 2021.

Early life and education

Born on January 25, 1860, in North Topeka,Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

, a year before Kansas was admitted as a state, Charles Curtis had three-eighths Native American ancestry and five-eighths European American ancestry. His mother, Ellen Papin (also spelled Pappan), was Kaw

Kaw or KAW may refer to:

Mythology

* Kaw (bull), a legendary bull in Meitei mythology

* Johnny Kaw, mythical settler of Kansas, US

* Kaw (character), in ''The Chronicles of Prydain''

People

* Kaw people, a Native American tribe

Places

* Kaw, Fr ...

, Osage The Osage Nation, a Native American tribe in the United States, is the source of most other terms containing the word "osage".

Osage can also refer to:

* Osage language, a Dhaegin language traditionally spoken by the Osage Nation

* Osage (Unicode b ...

, Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

, and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

. His father, Orren Curtis, was of English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, Scots, and Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

ancestry. On his mother's side, Curtis was a descendant of chief White Plume

White Plume (ca. 1765—1838), also known as Nom-pa-wa-rah, Manshenscaw, and Monchousia, was a chief of the Kaw (Kansa, Kanza) Indigenous American tribe. He signed a treaty in 1825 ceding millions of acres of Kaw land to the United States. Most p ...

of the Kaw Nation and chief Pawhuska

Pawhuska ( osa, 𐓄𐓘𐓢𐓶𐓮𐓤𐓘 / hpahúska, ''meaning: "White Hair"'', iow, Paháhga) is a city in and the county seat of Osage County, Oklahoma, United States. It was named after the 19th-century Osage chief, ''Paw-Hiu-Skah'', wh ...

of the Osage.

Curtis's first words as an infant were in French and Kansa, both languages that he learned from his mother. She died in 1863, when he was 3 years old, but he lived for some time thereafter with his maternal grandparents on the Kaw reservation and returned to them in later years. He learned to love racing horses and was later a highly successful jockey in prairie horse races., reprinted from

After Curtis's mother died in 1863, his father remarried but soon divorced. During his Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

service, Orren Curtis was captured and imprisoned. During that period, the toddler Charles was cared for by his maternal grandparents. They also later helped him gain possession of his mother's land in North Topeka; under the Kaw matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

system, he inherited it from her. His father tried unsuccessfully to get control of that land. Orren Curtis married a third time and had a daughter, Theresa Permelia "Dolly" Curtis, who was born in 1866, after the end of the war.

On June 1, 1868, 100 Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

warriors invaded the Kaw Reservation. The Kaw men painted their faces, donned regalia, and rode out on horseback to confront the Cheyenne. The rival Indian warriors put on a display of superb horsemanship, accompanied with war cries and volleys of bullets and arrows. Terrified white settlers took refuge in nearby Council Grove. After about four hours, the Cheyenne retired with a few stolen horses and a peace offering of coffee and sugar from the Council Grove merchants. No one had been injured on either side. During the battle, Joe Jim, a Kaw interpreter, galloped to Topeka to seek assistance from the governor. Riding with Jim was the eight-year-old Charles Curtis, then nicknamed "Indian Charley."

Curtis re-enrolled in the Kaw Nation

The Kaw Nation (or Kanza or Kansa) is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma and parts of Kansas. It comes from the central Midwestern United States. It has also been called the "People of the South wind",

, which had been removed from Kansas to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

when he was in his teens. Curtis was strongly influenced by both sets of grandparents. After living on the reservation with his maternal grandparents, M. Papin and Julie Gonville, he returned to the city of Topeka. There, he lived with his paternal grandparents while he attended Topeka High School

Topeka High School (THS) is a public secondary school in Topeka, Kansas, United States. It serves students in grades 9 to 12, and is one of five high schools operated by the Topeka USD 501 school district. In the 2010–2011 school year, there w ...

. Both grandmothers encouraged his education.

Curtis read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

in an established firm, where he worked part time. He was admitted to the bar in 1881 and began his practice in Topeka. He served as prosecuting attorney of Shawnee County, Kansas

Shawnee County (county code SN) is located in northeast Kansas, in the central United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 178,909, making it the third-most populous county in Kansas. Its most populous city, Topeka, is the state ...

, from 1885 to 1889.

Marriage and family

On November 27, 1884, Curtis married Annie Elizabeth Baird (1860–1924). They had three children: Permelia Jeannette Curtis (1886–1955), Henry "Harry" King Curtis (1890–1946), and Leona Virginia Curtis (1892–1965). He and his wife also provided a home in Topeka for his paternal sister Dolly Curtis before her marriage. His wife died in 1924. A widower when he was elected vice president in1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhanov, J ...

, Curtis had his long-since-married sister, Dolly Curtis Gann (March 1866 – January 30, 1953), act as his official hostess for social events. She had lived with her husband, Edward Everett Gann, in Washington, D.C., since about 1903. He was a lawyer and once an assistant attorney general in the government. Attuned to social protocol, Dolly Gann insisted in 1929 on being treated officially as the second woman in government at social functions. The diplomatic corps voted to change a State Department protocol to acknowledge that while her brother was in office.

To date, Curtis is the last vice president who was unmarried during his entire time in office. Alben W. Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was an American lawyer and politician from Kentucky who served in both houses of Congress and as the 35th vice president of the United States from 1949 to 1953 under Presiden ...

, who served as vice president from 1949 to 1953, entered office as a widower but remarried while in office.

House of Representatives (1893–1907)

First elected as aRepublican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

to the House of Representatives of the 53rd Congress

The 53rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1893, ...

, Curtis was re-elected for the following six terms. Naturally gregarious, he also made the effort to learn about his many constituents and treated them as personal friends.

In 1902, the Kaw Allotment Act disbanded the Kaw Nation as a legal entity and provided for the allotment of its communal land to members in a process similar to that experienced by other tribes. The act transferred 160 acres (0.6 km2) of former tribal land to the federal government. Other land that hand held in common was allocated to individual tribal members. Under the terms of the act, as enrolled tribal members, Curtis and his three children were allotted about 1,625 acres (6.6 km2) of Kaw land near Washunga in Oklahoma.

Curtis served several consecutive terms in the House from March 4, 1893, to January 28, 1907.

Senate (1907–1913, 1915–1929)

Curtis resigned from the House after he had been elected by the

Curtis resigned from the House after he had been elected by the Kansas Legislature

The Kansas Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kansas. It is a bicameral assembly, composed of the lower Kansas House of Representatives, with 125 state representatives, and the upper Kansas Senate, with 40 state senators. ...

to the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

seat that was left vacant by the resignation of Joseph R. Burton

Joseph Ralph Burton (November 16, 1852February 27, 1923) was a lawyer and United States Senator from the state of Kansas. He was the first Senator to be convicted of a crime. He served in the Kansas House of Representatives several times in the 18 ...

. Curtis served the remainder of his current term, which ended on March 4, 1907. (Popular election of U.S. senators had not yet been mandated by constitutional amendment.) At the same time, the legislature elected Curtis to the next full Senate term. From March 4, 1907, he served until March 3, 1913. In 1912, Democrats won control of the Kansas legislature and so Curtis was not re-elected.

The 17th Amendment, providing for direct popular election of Senators, was adopted in 1913. In 1914, Curtis was elected to Kansas's other Senate seat by popular vote and was re-elected in 1920 and 1926. In total, he served from March 4, 1915, to March 3, 1929, when he resigned to become vice president.

During his tenure in the Senate, Curtis was President pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase ''pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

, Chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Department of the Interior, of the Committee on Indian Depredations, and of the Committee on Coast Defenses; and Chairman of the Republican Senate Conference. He also was elected for a decade as Senate Minority Whip and for four years as Senate Majority Leader after Republicans won control of the chamber. He had experience in all the senior leadership positions in the Senate and was highly respected for his ability to work with members on both sides of the aisle.

In 1923, Curtis, together with his fellow Kansan Representative Daniel Read Anthony, Jr., proposed the first version of the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

to each of their Houses. The amendment did not pass.

Curtis's leadership abilities were demonstrated by his election as Republican Whip

Party leaders of the United States House of Representatives, also known as floor leaders, are congresspeople who coordinate legislative initiatives and serve as the chief spokespersons for their parties on the House floor. These leaders are ele ...

from 1915 to 1924 and Majority Leader

In U.S. politics (as well as in some other countries utilizing the presidential system), the majority floor leader is a partisan position in a legislative body.

from 1925 to 1929. He was effective in collaboration and moving legislation forward in the Senate. Idaho Senator William Borah

William Edgar Borah (June 29, 1865 – January 19, 1940) was an outspoken History of the United States Republican Party, Republican United States Senator, one of the best-known figures in History of Idaho, Idaho's history. A Progressivism ...

acclaimed Curtis as "a great reconciler, a walking political encyclopedia and one of the best political poker players in America." ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine featured him on the cover in December 1926 and reported that "it is in the party caucuses, in the committee rooms, in the cloakrooms that he patches up troubles, puts through legislation" as one of the two leading senators, the other being Reed Smoot

Reed Smoot (January 10, 1862February 9, 1941) was an American politician, businessman, and apostle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). First elected by the Utah State Legislature to the U.S. Senate in 1902, he served ...

.

Curtis was remembered for not making many speeches and was noted for keeping the "best card index of the state ever made." Curtis used a black notebook and later a card index to record all the people whom he met in office or while he was campaigning. He continually referred to it, which resulted in his being known for "his remarkable memory for faces and names:"

Curtis was celebrated as a " stand patter", the most regular of Republicans but also as a man who could always bargain with his party's progressives and with Senators from across the aisle.

Vice presidency (1929–1933)

Curtis received 64 votes on the presidential ballot at the1928 Republican National Convention

The 1928 Republican National Convention was held at Convention Hall in Kansas City, Missouri, from June 12 to June 15, 1928.

Because President Coolidge had announced unexpectedly he would not run for re-election in 1928, Commerce Secretary Her ...

in Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more ...

out of 1,084 total. The winning candidate, Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, secured 837 votes and had been the favorite for the nomination since August 1927, when President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

took himself out of contention. Curtis was a leader of the anti-Hoover movement and had formed an alliance with two of his Senate colleagues, Guy Goff and James E. Watson

James Eli Watson (November 2, 1864July 29, 1948) was a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Indiana. He was the Senate's second official majority leader. While an article published by the Senate (see References) gives his year of birth a ...

, as well as Governor Frank Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pre ...

of Illinois. Hoover's pedigree as a progressive follower of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

did not sit well with conservatives like Curtis. Less than a week before the convention, he described Hoover as a man "for whom the party will be on the defensive from the day he is named until the close of the polls on election day.". However, Curtis had no qualms about accepting the vice-presidential nomination.

Although Hoover gave few speeches during the 1928 presidential campaign, Curtis traveled coast to coast and spoke almost every day. While covering the convention, H. L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

described Curtis as "the Kansas comic character, who is half Indian and half windmill. Charlie ran against Hoover with great energy, and let fly some very embarrassing truths about him. But when the Hoover managers threw Charlie the Vice-Presidency as a solatium, he shut up instantly, and a few days later he was hymning his late bugaboo as the greatest statesman since Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelopo ...

."

The Hoover–Curtis ticket won the 1928 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1928.

Africa

* 1928 Southern Rhodesian general election

Asia

* 1928 Japanese general election

* 1928 Persian legislative election

* 1928 Philippine House of Representatives elections

* 1928 Philippin ...

in a landslide by receiving 444 out of the 531 Electoral College votes and 58.2% of the popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

. Curtis resigned from the Senate the day before he was sworn in as vice-president. After he took the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Such ...

in the Senate Chamber, the presidential party proceeded to the East Portico of the U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

for Hoover's inauguration. Curtis arranged for a Native American jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

band to perform at the inauguration.

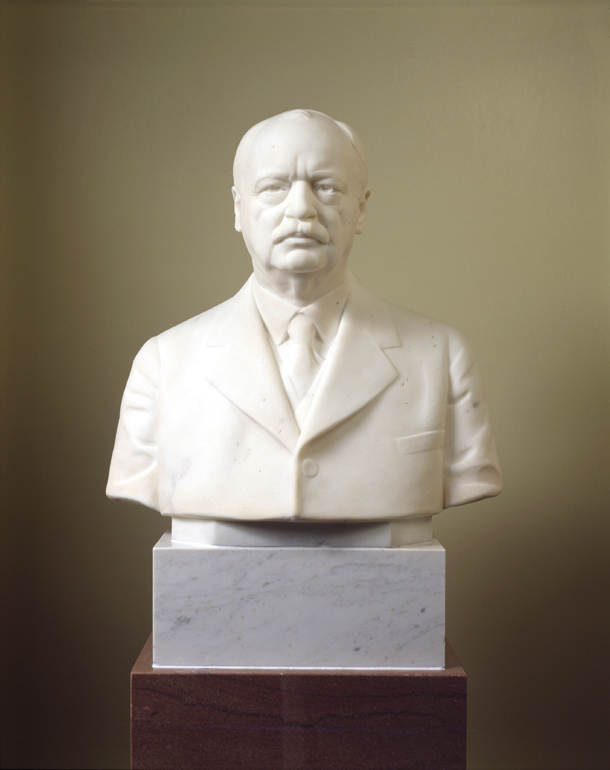

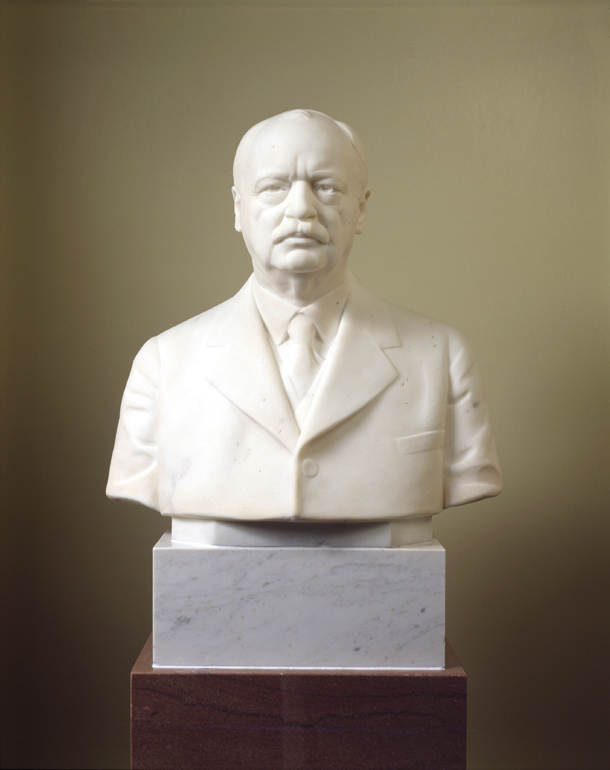

Curtis's election as vice president made history because he was the only native Kansan, the only Native American, and the first non-European to hold the post. The first person enrolled in a Native American tribe to be elected to such a high office, Curtis decorated his office with Native American artifacts and posed for pictures wearing Indian headdresses. He was 69 years old when he took office, which made him the oldest incoming vice-president at the time.

Curtis was the first vice-president to take the oath of office on a Bible in the same manner as the President. Curtis named Lola M. Williams as private secretary to the vice-president, and Williams was one of the first women to enter the Senate floor, which was traditionally a male monopoly.

Soon after the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

began, Curtis had endorsed the five-day work week

The weekdays and weekend are the complementary parts of the week devoted to labour and rest, respectively. The legal weekdays (British English), or workweek (American English), is the part of the seven-day week devoted to working. In most of th ...

with no reduction in wages as a work-sharing solution to unemployment. In October 1930, in the middle of the campaign for 1930 midterm elections, Curtis made an offhand remark that "good times are just around the corner". The statement was later erroneously attributed to Hoover and became a "lethal political boomerang."

At the 1932 Republican National Convention

The 1932 Republican National Convention was held at Chicago Stadium in Chicago, Illinois, from June 14 to June 16, 1932. It nominated President Herbert Hoover and Vice President Charles Curtis for reelection.

Hoover was virtually unopposed for ...

, Hoover was renominated almost unanimously. Curtis failed to secure a majority of votes on the first ballot for the vice-presidential nomination. He received 559.25 out of 1,154 votes (or 48.5%), with Generals Hanford MacNider

Lieutenant General Hanford MacNider (October 2, 1889 – February 18, 1968) was a senior officer of the United States Army who fought in both world wars. He also served as a diplomat, the Assistant Secretary of War of the United States from 192 ...

(15.8%) and James Harbord

Lieutenant General James Guthrie Harbord (March 21, 1866 – August 20, 1947) was a senior officer of the United States Army and president and chairman of the board of RCA.

Early life

Harbord was born in Bloomington, Illinois, the son of Geo ...

(14.0%) being his nearest contenders. On the second ballot, the Pennsylvania delegation shifted its votes to Curtis from Edward Martin, which gave him 634.25 votes (54.9%) and secured him the nomination for the second time.

Curtis opened the 1932 Summer Olympics

The 1932 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the X Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1932) were an international multi-sport event held from July 30 to August 14, 1932 in Los Angeles, California, United States. The Games were held duri ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

and so became the first U.S. executive branch officer to open the Olympic Games.

Curtis cast three tie-breaking votes in the Senate.

Following the stock market crash in 1929, the problems of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

deepened during the Hoover administration

Herbert Hoover's tenure as the 31st president of the United States began on his inauguration on March 4, 1929, and ended on March 4, 1933. Hoover, a Republican, took office after a landslide victory in the 1928 presidential election over Democr ...

and resulted in the defeat of the Republican ticket in 1932. The Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

was elected in 1932 as president, with a popular vote of 57% to 40%. Curtis's term as vice president ended on March 4, 1933. Curtis's final duty as vice president was to administer the oath of office to his successor, John Nance Garner

John Nance Garner III (November 22, 1868 – November 7, 1967), known among his contemporaries as "Cactus Jack", was an American History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician and lawyer from History of Texas, Texas who ...

, whose swearing-in ceremony was the last to take place in the Senate Chamber.

peace pipe

A ceremonial pipe is a particular type of smoking pipe, used by a number of cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in their sacred ceremonies. Traditionally they are used to offer prayers in a religious ceremony, to make a ceremonial ...

from Red Tomahawk, slayer of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

File:News-Week Feb 17 1933, vol1 issue1 (cropped).jpg, Vice President Curtis (standing) presiding over the count of the Electoral College votes of the 1932 election

Post-vice presidency (1933–1936)

Curtis decided to stay in

Curtis decided to stay in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, to resume his legal career, as he had a wide network of professional contacts from his long career in Congress and the executive branch. He participated in one of the earliest known triathlons in the city.

Curtis died from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

on February 8, 1936, at the age of 76. By his wishes, his body was returned to Kansas and buried next to his wife at the Topeka Cemetery

The Topeka Cemetery is a cemetery in Topeka, Kansas, United States. Established in 1859, it is the oldest chartered cemetery in the state of Kansas.

The 80-acre cemetery had more than 35,000 burials by 2019, including several prominent Kansans. Am ...

.

Legacy and honors

Curtis was the first multiracial person to serve asVice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, and was the only one until Kamala Harris

Kamala Devi Harris ( ; born October 20, 1964) is an American politician and attorney who is the 49th vice president of the United States. She is the first female vice president and the highest-ranking female official in U.S. history, as well ...

was inaugurated in 2021. Curtis was also the only United States vice president to have inaugurated the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

. Over the course of his career, Curtis was featured on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine on three occasions. Two of these appearances – on December 20, 1926, and June 18, 1928 – occurred while Curtis was a senator. The third occasion was December 5, 1932, during the final months of his vice presidency.

Curtis' house in Topeka, Kansas

Topeka ( ; Kansa language, Kansa: ; iow, Dópikˀe, script=Latn or ) is the Capital (political), capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the County seat, seat of Shawnee County, Kansas, Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the ...

is now operated as a historic house museum

A historic house museum is a house of historic significance that has been transformed into a museum. Historic furnishings may be displayed in a way that reflects their original placement and usage in a home. Historic house museums are held to a ...

known as the Charles Curtis House Museum. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

and designated as a state historic site.

See also

Unfinished autobiography

edited by Kitty Frank and confirmed by the Kansas State Historical Society *

Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act; it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw ...

* List of Chairpersons of the College Republicans

* List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s – December 20, 1926, and June 18, 1928

* List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1930s – December 5, 1932

* List of Native Americans in the United States Congress

This is a list of Native Americans with documented tribal ancestry or affiliation in the U.S. Congress.

All entries on this list are related to Native American tribes based in the contiguous United States. There are Native Hawaiians who have se ...

References

Sources

* * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

"Charles Curtis; Native-American Indian Vice-President; a biography"

, Vice President Charles Curtis Website

Moro Films official movie web site

Don C. Seitz, ''From Kaw Teepee to Capitol; The Life Story of Charles Curtis, Indian, Who Has Risen to High Estate''

full text, Hathi Trust Digital Library

Charles Curtis House Museum

, official website *

by Deb Goodrich

Image of Vice-President Charles Curtis at a banquet on-board a military ship, Los Angeles (?), 1932.

''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

'' Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library

The Charles E. Young Research Library is one of the largest libraries on the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles in Westwood, Los Angeles, California. It initially opened in 1964, and a second phase of construction was completed ...

, University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Curtis, Charles

1860 births

1936 deaths

19th-century Native Americans

19th-century American politicians

1928 United States vice-presidential candidates

1932 United States vice-presidential candidates

20th-century vice presidents of the United States

20th-century Native Americans

American people of French descent

American people of English descent

American people of Osage descent

American people of Potawatomi descent

American people of Scottish descent

American people of Welsh descent

American prosecutors

Hoover administration cabinet members

Kansas lawyers

Kaw people

Lawyers from Washington, D.C.

Native American Christians

Native American lawyers

Native American politicians

Native American candidates for Vice President of the United States

Native American members of the United States Congress

American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law

Politicians from Topeka, Kansas

Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate

Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kansas

Republican Party United States senators from Kansas

Republican Party vice presidents of the United States

Vice presidents of the United States

Washington, D.C., Republicans

People buried in Topeka Cemetery

Topeka High School alumni