Charles Carroll of Carrollton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

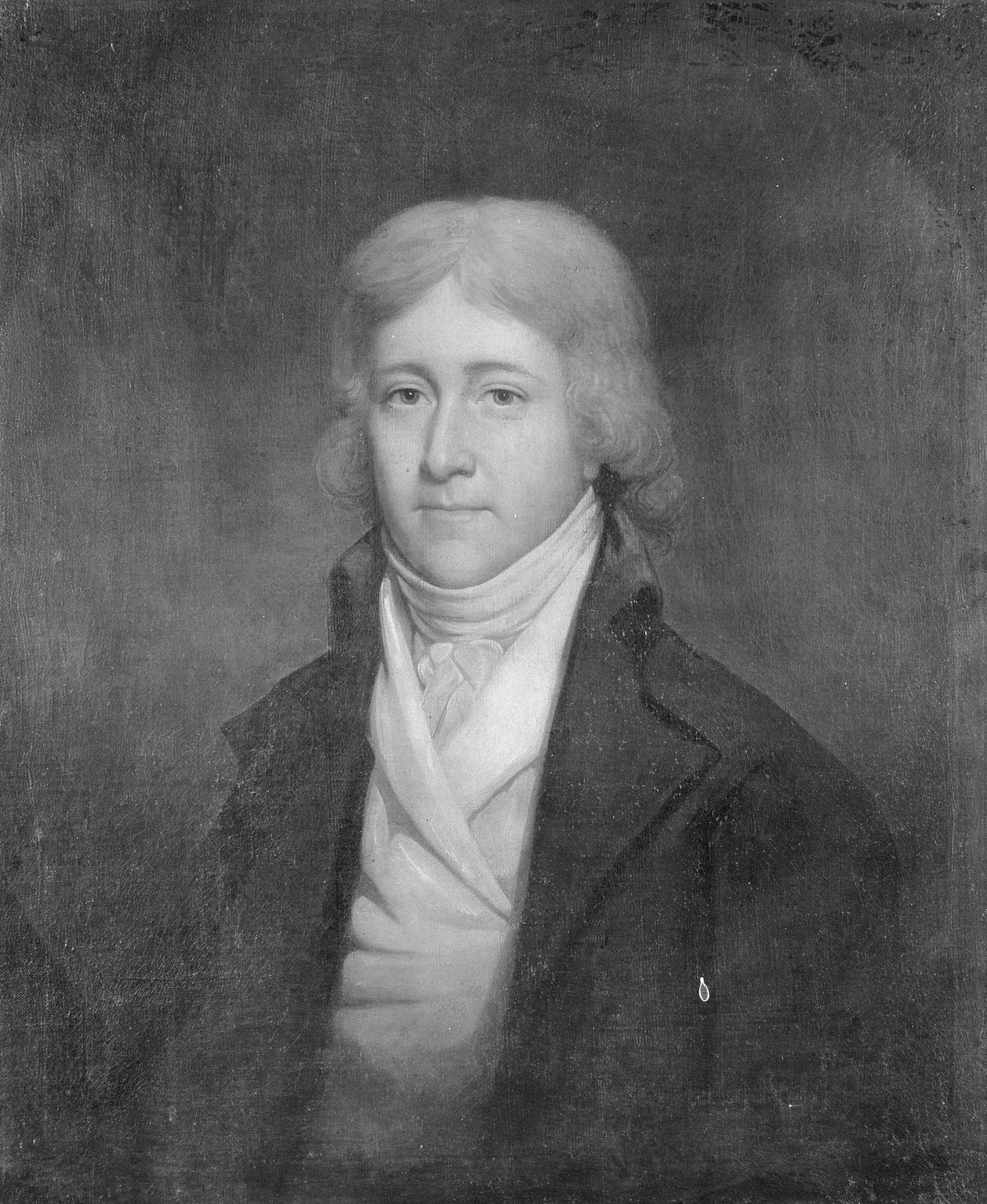

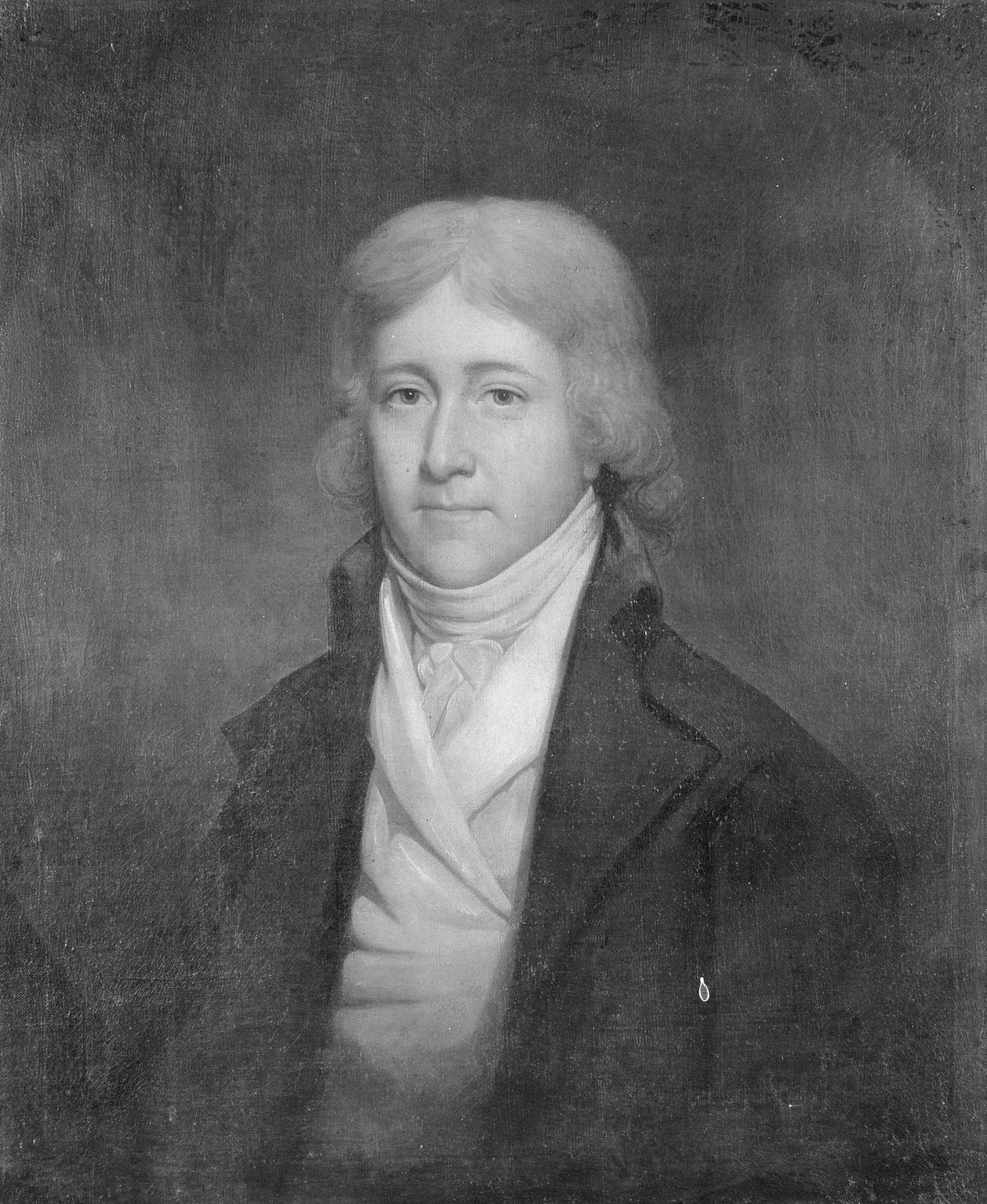

Charles Carroll (September 19, 1737 – November 14, 1832), known as Charles Carroll of Carrollton or Charles Carroll III, was an Irish-American politician, planter, and signatory of the

The Carroll family were descendants of the Ó Cearbhaill's, who were the rulers of the Irish

The Carroll family were descendants of the Ó Cearbhaill's, who were the rulers of the Irish

Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, the only child of Charles Carroll of Annapolis and his wife Elizabeth Brooke. He was born an illegitimate child, as his parents were not married at the time of his birth, for technical reasons to do with the inheritance of the Carroll family estates. They eventually married in 1757. The young Carroll was educated at a Jesuit preparatory school known as Bohemia Manor in

Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, the only child of Charles Carroll of Annapolis and his wife Elizabeth Brooke. He was born an illegitimate child, as his parents were not married at the time of his birth, for technical reasons to do with the inheritance of the Carroll family estates. They eventually married in 1757. The young Carroll was educated at a Jesuit preparatory school known as Bohemia Manor in

Retrieved November 2010. owning extensive agricultural estates, most notably the large manor at

Retrieved August 2012 But as the dispute between

Retrieved November 2010. In these debates, Carroll argued that the government of Maryland had long been the monopoly of four families, the Ogles, the Taskers, the Bladens and the Dulanys, with Dulany taking the contrary view. Eventually word spread of the true identity of the two combatants, and Carroll's fame and notoriety began to grow.McClanahan, Brion T., p.203, ''The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers''

Retrieved November 2010. Dulany soon resorted to highly personal ad hominem attacks on "First Citizen", and Carroll responded, in statesmanlike fashion, with considerable restraint, arguing that when "Antillon" engaged in "virulent invective and illiberal abuse, we may fairly presume, that arguments are either wanting, or that ignorance or incapacity know not how to apply them". Following these written debates, Carroll became a leading opponent of British rule and served on various committees of correspondence. In the early 1770s Carroll appears to have embraced the idea that only violence could break the impasse with Great Britain. According to legend, Carroll and

Retrieved November 2010.

Carroll was elected to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and remained a delegate until 1778. He arrived too late to vote in favor of the

Carroll was elected to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and remained a delegate until 1778. He arrived too late to vote in favor of the

Carroll retired from public life in 1801. After Thomas Jefferson became president, he had great anxiety about political activity and was not sympathetic to the

Carroll retired from public life in 1801. After Thomas Jefferson became president, he had great anxiety about political activity and was not sympathetic to the  Named in his honor are counties in

Named in his honor are counties in

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of ...

. He was the only Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

signatory and the last surviving signatory of the Declaration of Independence, dying 56 years after signing the document.

Considered one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the war for independence from Great Britai ...

, Carroll was known contemporaneously as the "First Citizen" of the American Colonies, a consequence of signing articles in the ''Maryland Gazette'' with that pen name. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

and Confederation Congress. Carroll later served as the first United States Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and p ...

for Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

. Of all of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, Carroll was reputed to be the wealthiest and most formally educated of the group. A product of his 17-year Jesuit education in France, Carroll spoke five languages fluently.

Born in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, Carroll inherited vast agricultural estates and was regarded as the wealthiest man in the American colonies when the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

commenced in 1775. His personal fortune at this time was reputed to be 2,100,000 pounds sterling, the (US$375 million). In addition, Carroll presided over his manor in Maryland, a 10,000-acre estate which held approximately 300 slaves. Though barred from holding office in Maryland because of his religion, Carroll emerged as a leader of the state's movement for independence. He was a delegate to the Annapolis Convention and was selected as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1776. He was part of an unsuccessful diplomatic mission, which also included Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a m ...

and Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

, that Congress sent to Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

in hopes of winning the support of French Canadians.

Carroll served in the Maryland Senate

The Maryland Senate, sometimes referred to as the Maryland State Senate, is the upper house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland. Composed of 47 senators elected from an equal number of constituent single- ...

from 1781 to 1800. He was elected as one of Maryland's inaugural representatives in the United States Senate but resigned from the United States Senate in 1792 after Maryland passed a law barring individuals from simultaneously serving in state and federal office. After retiring from public office, he helped establish the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

.

Ancestry

The Carroll family were descendants of the Ó Cearbhaill's, who were the rulers of the Irish

The Carroll family were descendants of the Ó Cearbhaill's, who were the rulers of the Irish petty kingdom

A petty kingdom is a kingdom described as minor or "petty" (from the French 'petit' meaning small) by contrast to an empire or unified kingdom that either preceded or succeeded it (e.g. the numerous kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England unified into ...

of Éile in King's County, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. Carroll's grandfather was Charles Carroll the Settler, an Irishman from Aghagurty

Aghagurty () is a townland in County Offaly, Ireland. It is approximately in area. Aghagurty was the ancestral home of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Catholic signatory of the American Declaration of Independence, whose grandfather, Char ...

who moved to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in 1685 and worked as a clerk for English nobleman Lord Powis before immigrating to Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

on October 1688. After arriving in Maryland, he settled in the colonial capital of St. Mary's City with a commission as an attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

from the colony's proprietor, Lord Baltimore.

Carroll's father was Charles Carroll of Annapolis, who was born in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

in 1702. Though he inherited the plantation of Doughoregan Manor

Doughoregan Manor () is a plantation house and estate located on Manor Lane west of Ellicott City, Maryland, United States. Established in the early 18th century as the seat of Maryland's prominent Carroll family, it was home to Founding Fath ...

from his father, as a Roman Catholic he was forbidden from participating in the political affairs of the colony.

Early life

Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, the only child of Charles Carroll of Annapolis and his wife Elizabeth Brooke. He was born an illegitimate child, as his parents were not married at the time of his birth, for technical reasons to do with the inheritance of the Carroll family estates. They eventually married in 1757. The young Carroll was educated at a Jesuit preparatory school known as Bohemia Manor in

Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, the only child of Charles Carroll of Annapolis and his wife Elizabeth Brooke. He was born an illegitimate child, as his parents were not married at the time of his birth, for technical reasons to do with the inheritance of the Carroll family estates. They eventually married in 1757. The young Carroll was educated at a Jesuit preparatory school known as Bohemia Manor in Cecil County

Cecil County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland at the northeastern corner of the state, bordering both Pennsylvania and Delaware. As of the 2020 census, the population was 103,725. The county seat is Elkton. The county was n ...

on Maryland's Eastern Shore Eastern Shore may refer to:

* Eastern Shore (Nova Scotia), a region

* Eastern Shore (electoral district), a provincial electoral district in Nova Scotia

* Eastern Shore of Maryland, a region

* Eastern Shore of Virginia, a region

* Eastern Shore (Al ...

. At age 11, he was sent to France, where he continued in Jesuit schools, first at the College of St. Omer in Northern France and later the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, graduating in 1755. He continued his studies in Europe and read law in London before returning to Annapolis in 1765.Maier, Pauline. ''The Old Revolutionaries'' (1980), />

Charles Carroll of Annapolis granted Carrollton Manor to his son, Charles Carroll of Carrollton. It is from this tract of land that he took his title "Charles Carroll of Carrollton." Like his father, Carroll was a Catholic and as a consequence was barred by Maryland statute from entering politics, practicing law and voting. This did not prevent him from becoming one of the wealthiest men in Maryland (or indeed anywhere in the Colonies),McClanahan, Brion T., p.199, ''The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers''Retrieved November 2010. owning extensive agricultural estates, most notably the large manor at

Doughoregan

Doughoregan Manor () is a plantation house and estate located on Manor Lane west of Ellicott City, Maryland, United States. Established in the early 18th century as the seat of Maryland's prominent Carroll family, it was home to Founding Fath ...

, Hockley Forge and Mill, and providing capital to finance new enterprises on the Western Shore.

American Revolution

Voice for independence

Carroll was not initially interested in politics, and in any event Catholics had been barred from holding office in Maryland since the 1704 act seeking "to prevent the growth of Popery in this Province".Roark, Elisabeth Louise, p.78, Artists of colonial AmericaRetrieved August 2012 But as the dispute between

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and her American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

intensified in the early 1770s, Carroll became a powerful voice for independence. In 1772, he engaged in a debate, conducted through anonymous newspaper letters, maintaining the right of the colonies to control their own taxation. Writing in the '' Maryland Gazette'' under the pseudonym "First Citizen," he became a prominent spokesman against the governor's proclamation increasing legal fees to state officers and Protestant clergy. Opposing Carroll in these written debates and writing as "Antillon" was Daniel Dulany the Younger, a noted lawyer and loyalist politician.Warfield, J. D., p. 215, ''The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland''Retrieved November 2010. In these debates, Carroll argued that the government of Maryland had long been the monopoly of four families, the Ogles, the Taskers, the Bladens and the Dulanys, with Dulany taking the contrary view. Eventually word spread of the true identity of the two combatants, and Carroll's fame and notoriety began to grow.McClanahan, Brion T., p.203, ''The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers''

Retrieved November 2010. Dulany soon resorted to highly personal ad hominem attacks on "First Citizen", and Carroll responded, in statesmanlike fashion, with considerable restraint, arguing that when "Antillon" engaged in "virulent invective and illiberal abuse, we may fairly presume, that arguments are either wanting, or that ignorance or incapacity know not how to apply them". Following these written debates, Carroll became a leading opponent of British rule and served on various committees of correspondence. In the early 1770s Carroll appears to have embraced the idea that only violence could break the impasse with Great Britain. According to legend, Carroll and

Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

(who would also later sign the Declaration of Independence on Maryland's behalf) had the following exchange:

:Chase: "We have the better of our opponents; we have completely written them down."

:Carroll: "And do you think that writing will settle the question between us?"

:Chase: "To be sure, what else can we resort to?"

:Carroll: "The bayonet. Our arguments will only raise the feelings of the people to that pitch, when open war will be looked to as the arbiter of the dispute."McClanahan, Brion T., p.204, ''The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers''Retrieved November 2010.

Continental Congress

Beginning with his election to Maryland's committee of correspondence in 1774, Carroll represented the colony in most of the pre-revolutionary groups. He became a member of Annapolis' first committee of safety in 1775. Carroll was a delegate to the Annapolis Convention, which functioned as Maryland's revolutionary government before the Declaration of Independence. In early 1776, the Congress sent him on a four-man diplomatic mission to the Province of Quebec, in order to seek assistance from French Canadians in the coming confrontation with Great Britain. Carroll was an excellent choice for such a mission, being fluent in French and a Catholic and therefore well suited to negotiations with the French-speaking Catholics of Quebec. He was joined in the commission byBenjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a m ...

, Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

, and his cousin John Carroll. The commission did not accomplish its mission. Carroll was elected to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and remained a delegate until 1778. He arrived too late to vote in favor of the

Carroll was elected to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and remained a delegate until 1778. He arrived too late to vote in favor of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of ...

but was present to sign the official document that survives today. After both Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

died on July 4, 1826, Carroll became the last living signatory of the Declaration of Independence. His signature reads "Charles Carroll of Carrollton" to distinguish him from his father, " Charles Carroll of Annapolis," who was still living at that time, and several other Charles Carrolls in Maryland, such as Charles Carroll, Barrister, and his son Charles Carroll, Jr., also known as "Charles Carroll of Homewood." He is usually referred to this way by historians. At the time, he was the richest man in America and had much to lose by identifying himself on the document. Throughout his term in the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named " United Colonies" and in ...

, he served on the board of war. Carroll also gave considerable financial support to the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

.

Senator

Carroll returned to Maryland in 1778 to assist in the formation of a state government. Carroll was re-elected to the Continental Congress in 1780, but he declined. He was elected to theMaryland Senate

The Maryland Senate, sometimes referred to as the Maryland State Senate, is the upper house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland. Composed of 47 senators elected from an equal number of constituent single- ...

in 1781 and served there until 1800. In November 1779, The Maryland House of Delegates moved to pass a bill confiscating the property of those who had sided with the Crown during the Revolution. Carroll opposed this measure, questioning the motives of those who pressed for confiscation and arguing that the measure was unjust. However, such moves to confiscate Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

property had much popular support and eventually, in 1780, the measure passed.

When the United States government was created, the Maryland legislature elected him to the first United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and ...

. In 1792, Maryland passed a law that prohibited any man from serving in the state and national legislatures at the same time. Since he preferred to be in the Maryland Senate, he resigned from the U.S. Senate on November 30, 1792.

Attitude toward slavery

The Carroll family were slaveholders, and Carroll was reputedly the largest single slave-owner at the time of the American Revolution. Carroll was opposed in principle to slavery, asking rhetorically: "Why keep alive the question of slavery? It is admitted by all to be a great evil." However, although he supported its gradual abolition, he did not free his own slaves. Carroll introduced a bill for the gradual abolition of slavery in the Maryland Senate, but it did not pass. In 1828, aged 91, he served as president of the Auxiliary State Colonization Society of Maryland, the Maryland branch of the American Colonization Society, an organization dedicated to returning black Americans to lead free lives in African states such asLiberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. It ...

.

Later life and legacy

Carroll retired from public life in 1801. After Thomas Jefferson became president, he had great anxiety about political activity and was not sympathetic to the

Carroll retired from public life in 1801. After Thomas Jefferson became president, he had great anxiety about political activity and was not sympathetic to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It ...

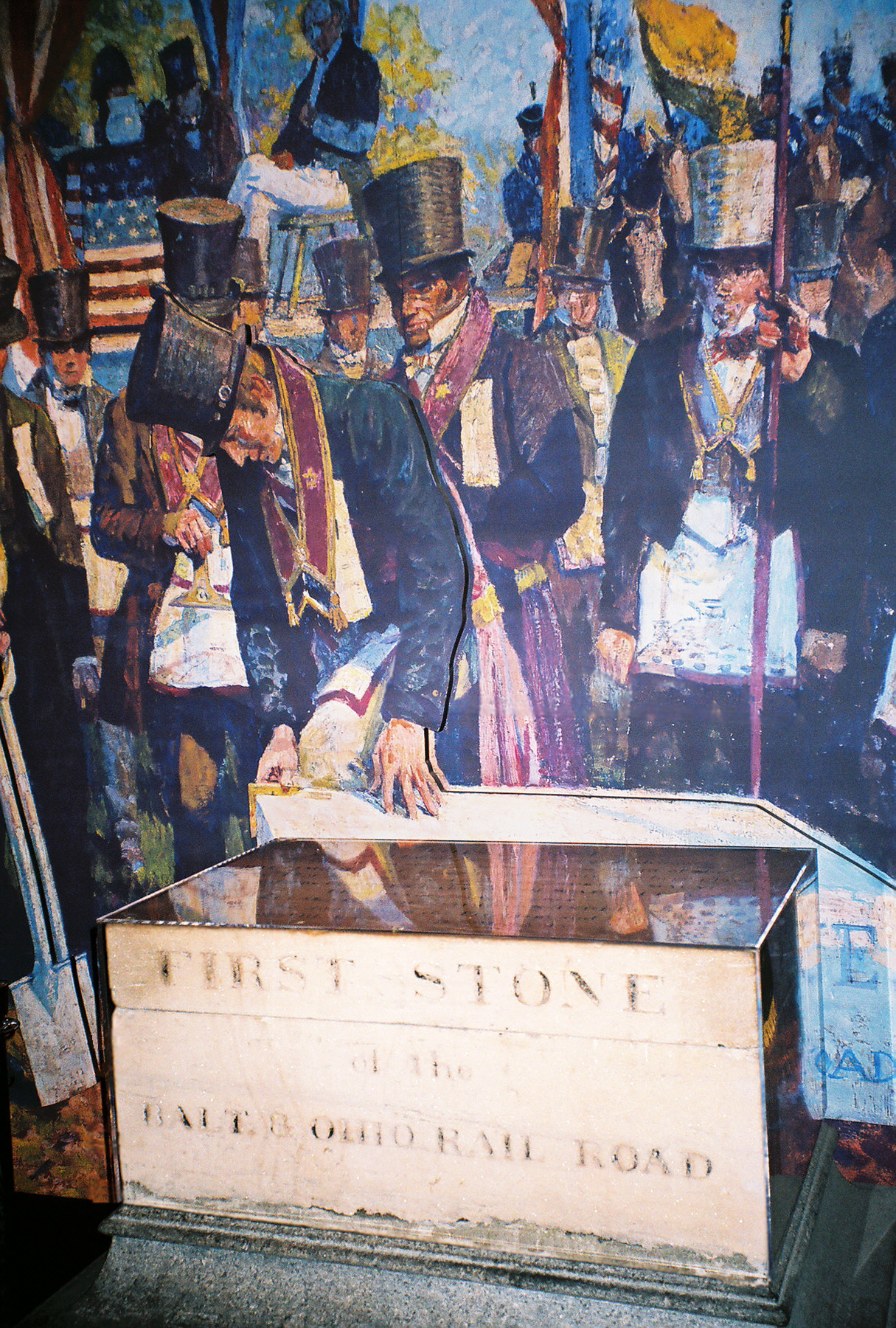

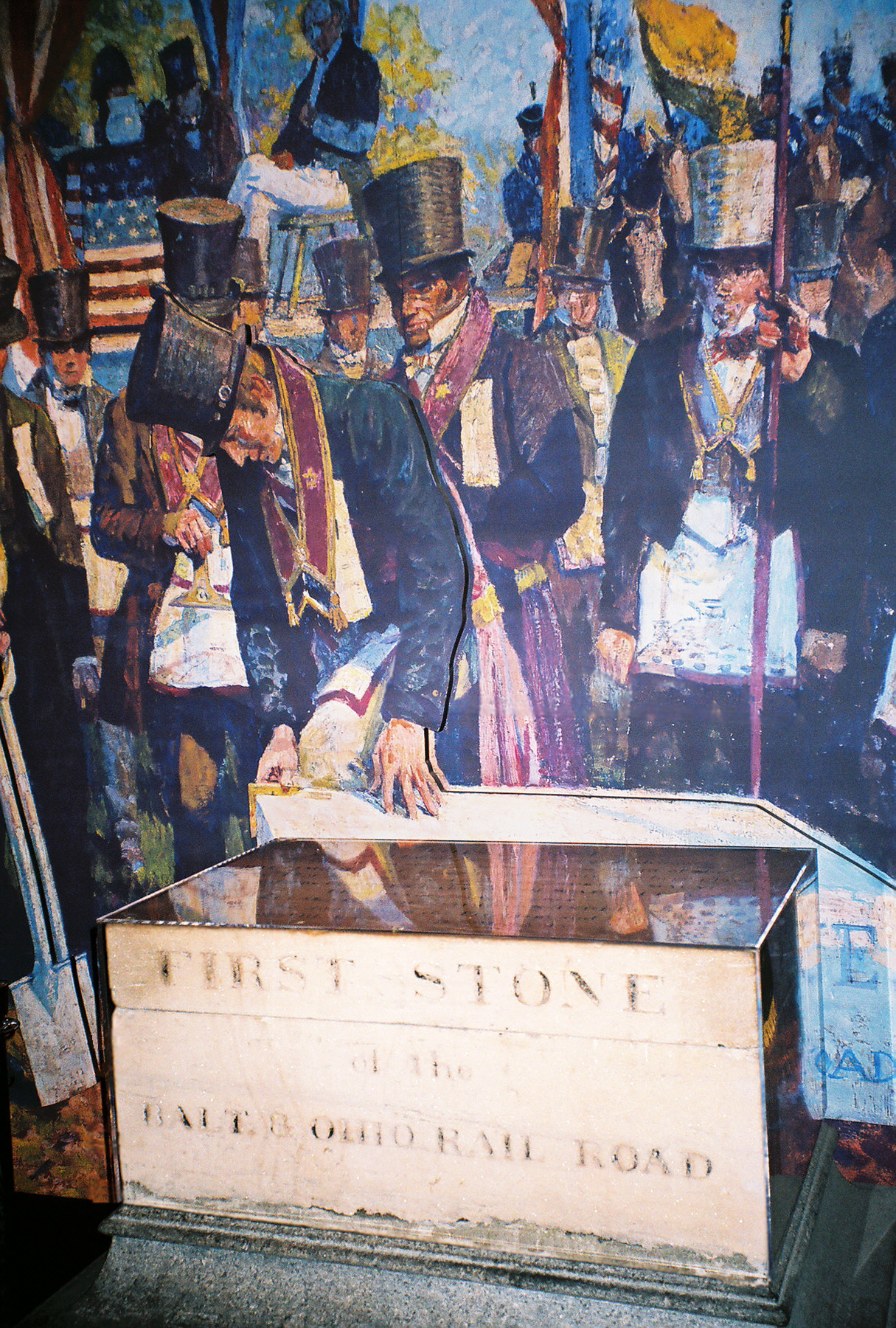

. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1815. Carroll came out of retirement to help create the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

in 1827. In 1828, he commissioned the Phoenix Shot Tower and laid its cornerstone, which was the tallest building in the United States until the Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk shaped building within the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, once commander-in-chief of the Continental Army (1775–1784) in the American Revolutionary War and ...

was constructed. His last public act, on July 4, 1828, was the laying of the "first stone" (cornerstone) of the railroad at almost 91 years of age.

He was admitted as an honorary member of The Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

in the state of Maryland in 1828. Unlike hereditary members, honorary members are not eligible to be represented by a living descendant. In May 1832, he was asked to appear at the first Democratic Party Convention but did not attend on account of poor health. Carroll died on November 14, 1832, at age 95, in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. He holds the distinction of being the oldest lived Founding Father. He had outlived four of the first six U.S. presidents. His funeral took place at the Baltimore Cathedral (now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary), and he is buried in his Doughoregan Manor Chapel at Ellicott City, Maryland

Ellicott City is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in, and the county seat of, Howard County, Maryland, Howard County, Maryland, United States. Part of the Baltimore metropolitan area, its population was 65,834 at the United ...

.

Carroll is remembered in the third stanza of the former state song '' Maryland, My Maryland''.

:Thou wilt not cower in the dust,

:Maryland! My Maryland!

:Thy beaming sword shall never rust,

:Maryland! My Maryland!

:Remember Carroll's sacred trust,

:Remember Howard's warlike thrust –

:And all thy slumberers with the just,

:Maryland! My Maryland!

Named in his honor are counties in

Named in his honor are counties in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Roc ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Mis ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

, and Virginia

Virginia, off