Charles Barry (actor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the

While in Rome he had met Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, through whom he met

While in Rome he had met Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, through whom he met  Two further Gothic churches in Lancashire, not for the Commissioners followed in 1824:

Two further Gothic churches in Lancashire, not for the Commissioners followed in 1824:  His last work in Manchester was the Italianate Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39), this is now part of Manchester Art Gallery. From 1835–37, he rebuilt

His last work in Manchester was the Italianate Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39), this is now part of Manchester Art Gallery. From 1835–37, he rebuilt

A major focus of his career was the remodelling of older

A major focus of his career was the remodelling of older  Highclere Castle, Hampshire, with its large tower, was remodelled between about 1842 and 1850, in

Highclere Castle, Hampshire, with its large tower, was remodelled between about 1842 and 1850, in  James Paine's

James Paine's  Barry's last major remodelling work was

Barry's last major remodelling work was

Barry remodelled Trafalgar Square (1840–45) he designed the north terrace with the steps at either end, and the sloping walls on the east and west of the square, the two fountain basins are also to Barry's design, although Edwin Lutyens re-designed the actual fountains (1939).Bradley & Pevsner, pp. 257–258

Barry was commissioned to design (1840–42) the facade of Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville prison, that was designed by Joshua Jebb, he added a stuccoed Italianate pilastered frontage to Caledonian Road. The (Old) Treasury (Now Cabinet Office) Whitehall by John Soane, built (1824–26) was virtually rebuilt by Barry (1844–47). It consists of 23 bays with a giant Corinthian order over a Rustication (architecture), rusticated ground floor, the five bays at each end project slightly from the facade.

Bridgewater House, Westminster, London (1845–64) for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, in a grand Italianate style. The structure was complete by 1848, but interior decoration was only finished by 1864. The main (south) front is 144 feet long, of nine bays in more massive version of his earlier Reform Club, the garden (west) front is of seven bays. The interiors are intact apart from the north wing which was bombed in The Blitz. The main interior is the central Saloon, a roofed courtyard of two storeys, of three by five bays of arches on each floor, the walls are lined with scagliola, the coved ceiling is glazed and the centre has three glazed saucer domes. The decoration of the major rooms is not the work of Barry.

Barry remodelled Trafalgar Square (1840–45) he designed the north terrace with the steps at either end, and the sloping walls on the east and west of the square, the two fountain basins are also to Barry's design, although Edwin Lutyens re-designed the actual fountains (1939).Bradley & Pevsner, pp. 257–258

Barry was commissioned to design (1840–42) the facade of Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville prison, that was designed by Joshua Jebb, he added a stuccoed Italianate pilastered frontage to Caledonian Road. The (Old) Treasury (Now Cabinet Office) Whitehall by John Soane, built (1824–26) was virtually rebuilt by Barry (1844–47). It consists of 23 bays with a giant Corinthian order over a Rustication (architecture), rusticated ground floor, the five bays at each end project slightly from the facade.

Bridgewater House, Westminster, London (1845–64) for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, in a grand Italianate style. The structure was complete by 1848, but interior decoration was only finished by 1864. The main (south) front is 144 feet long, of nine bays in more massive version of his earlier Reform Club, the garden (west) front is of seven bays. The interiors are intact apart from the north wing which was bombed in The Blitz. The main interior is the central Saloon, a roofed courtyard of two storeys, of three by five bays of arches on each floor, the walls are lined with scagliola, the coved ceiling is glazed and the centre has three glazed saucer domes. The decoration of the major rooms is not the work of Barry.

The last major commission of Barry's was Halifax Town Hall (1859–62), in a North Italian Cinquecento style, and a grand tower with spire, the interior includes a central hall similar to that at Bridgewater House, the building was completed after Barry's death by his son Edward Middleton Barry.

Completed after Barry's death in 1863 was the classical, John Josiah Guest, Guest Memorial Reading Room and Library in Dowlais, Wales.

The most significant of Barry's designs that were not carried out included, his proposed Law Courts (1840–41), that if built would have covered Lincoln's Inn Fields with a large Greek Revival building, this rectangular building would have been over three hundred by four hundred feet, in a Greek Doric style, there would have been octastyle porticoes in the middle of the shorter sides and hexastyle porticoes on the longer sides, leading to a large central hall that would have been surrounded by twelve court rooms that in turn were surrounded by the ancillary facilities. Later was his General Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements, that were exhibited in 1857. This comprehensive scheme was for the redevelopment of much of Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade, the embankment of the River Thames on both sides of the river in the areas to the north and south of the Palace of Westminster, this would eventual be partially realised as the Victoria Embankment and Albert Embankment, three new bridges across the Thames, a vast Hotel where Charing Cross railway station was later built, the enlargement of the National Gallery (Barry's son Edward would later extend the Gallery) and new buildings around Trafalgar Square and along the new embankments and the recently created Victoria Street. There were also several new roads proposed on both sides of the Thames. The largest of the proposed buildings would have been even larger than the Palace of Westminster, this was the Government Offices, this vast building would have covered the area stretching from horse Guards Parade across Downing Street and the sites of the future Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Government Offices Great George Street, HM Treasury on Whitehall up to Parliament Square. It would have had a vast glass-roofed hall, 320 by 150 feet, at the centre of the building. The plan was to house all government departments apart from the Admiralty in the building. The building would have been in a Classical style incorporating Barry's existing Treasury building.

The last major commission of Barry's was Halifax Town Hall (1859–62), in a North Italian Cinquecento style, and a grand tower with spire, the interior includes a central hall similar to that at Bridgewater House, the building was completed after Barry's death by his son Edward Middleton Barry.

Completed after Barry's death in 1863 was the classical, John Josiah Guest, Guest Memorial Reading Room and Library in Dowlais, Wales.

The most significant of Barry's designs that were not carried out included, his proposed Law Courts (1840–41), that if built would have covered Lincoln's Inn Fields with a large Greek Revival building, this rectangular building would have been over three hundred by four hundred feet, in a Greek Doric style, there would have been octastyle porticoes in the middle of the shorter sides and hexastyle porticoes on the longer sides, leading to a large central hall that would have been surrounded by twelve court rooms that in turn were surrounded by the ancillary facilities. Later was his General Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements, that were exhibited in 1857. This comprehensive scheme was for the redevelopment of much of Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade, the embankment of the River Thames on both sides of the river in the areas to the north and south of the Palace of Westminster, this would eventual be partially realised as the Victoria Embankment and Albert Embankment, three new bridges across the Thames, a vast Hotel where Charing Cross railway station was later built, the enlargement of the National Gallery (Barry's son Edward would later extend the Gallery) and new buildings around Trafalgar Square and along the new embankments and the recently created Victoria Street. There were also several new roads proposed on both sides of the Thames. The largest of the proposed buildings would have been even larger than the Palace of Westminster, this was the Government Offices, this vast building would have covered the area stretching from horse Guards Parade across Downing Street and the sites of the future Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Government Offices Great George Street, HM Treasury on Whitehall up to Parliament Square. It would have had a vast glass-roofed hall, 320 by 150 feet, at the centre of the building. The plan was to house all government departments apart from the Admiralty in the building. The building would have been in a Classical style incorporating Barry's existing Treasury building.

Following the Burning of Parliament, destruction by fire of the old Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, a competition was held to find a suitable design, for which there were 97 entries. Barry's entry, number 64, for which Augustus Pugin helped prepare the competition drawings, won the commission in January 1836 to design the new Palace of Westminster. His collaboration with Pugin, who designed furniture, stained glass, sculpture, wallpaper, decorative floor tiles and mosaic work, was not renewed until June 1844, and then continued until Pugin's mental breakdown and death in 1852. The Tudor Gothic architecture, Gothic architectural style was chosen to complement the Henry VII Lady Chapel opposite. The design had to incorporate those parts of the building that escaped destruction, most notably Westminster Hall, the adjoining double-storey cloisters of St Stephen's court and the crypt of St Stephen's Chapel. Barry's design was parallel to the River Thames, but the surviving buildings were at a slight angle to the river, so Barry had to incorporate the awkwardly different axes into the design. Although the design included most of the elements of the finished building, including the two towers at either end of the building, it would undergo significant redesign. The winning design was only about in length, about two-thirds the size of the finished building. The central lobby and tower were later additions, as was the extensive royal suite at the southern end of the building. The amended design on which construction commenced was approximately the same size as the finished building, although both the Victoria Tower and Clock Tower were considerably taller in the finished building, and the Central Tower was not yet part of the design.

Following the Burning of Parliament, destruction by fire of the old Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, a competition was held to find a suitable design, for which there were 97 entries. Barry's entry, number 64, for which Augustus Pugin helped prepare the competition drawings, won the commission in January 1836 to design the new Palace of Westminster. His collaboration with Pugin, who designed furniture, stained glass, sculpture, wallpaper, decorative floor tiles and mosaic work, was not renewed until June 1844, and then continued until Pugin's mental breakdown and death in 1852. The Tudor Gothic architecture, Gothic architectural style was chosen to complement the Henry VII Lady Chapel opposite. The design had to incorporate those parts of the building that escaped destruction, most notably Westminster Hall, the adjoining double-storey cloisters of St Stephen's court and the crypt of St Stephen's Chapel. Barry's design was parallel to the River Thames, but the surviving buildings were at a slight angle to the river, so Barry had to incorporate the awkwardly different axes into the design. Although the design included most of the elements of the finished building, including the two towers at either end of the building, it would undergo significant redesign. The winning design was only about in length, about two-thirds the size of the finished building. The central lobby and tower were later additions, as was the extensive royal suite at the southern end of the building. The amended design on which construction commenced was approximately the same size as the finished building, although both the Victoria Tower and Clock Tower were considerably taller in the finished building, and the Central Tower was not yet part of the design.

Before construction could commence, the site had to be Thames Embankment, embanked and cleared of the remains of the previous buildings, and various sewerage, sewers needed to be diverted. On 1 September 1837, work started on building a long coffer-dam to enclose the building site along the river. The construction of the embankment started on New Year's Day 1839.Port, p. 198 The first work consisted of the construction of a vast concrete raft to serve as the building's foundation. After the space had been excavated by hand, of concrete were laid. The site of the Victoria Tower was found to consist of quicksand, necessitating the use of deep foundation, piles. The stone selected for the exterior of the building was quarried at Anston in Yorkshire, with the core of the walls being laid in brick. To make the building as fire-proof as possible, wood was only used decoratively, rather than structurally, and extensive use was made of cast iron. The roofs of the building consist of cast iron girders covered by sheets of iron, cast iron beams were also used as joists to support the floors and extensively in the internal structures of both the clock tower and Victoria tower.

Barry and his engineer Alfred Meeson were responsible for designing scaffolding, hoist (device), hoists and crane (machine), cranes used in the construction. One of their most innovative developments was the scaffolding used to construct the three main towers. For the central tower they designed an inner rotating scaffold, surrounded by timber centring to support the masonry vault of the Central Lobby, that spans , and an external timber tower. A portable steam engine was used to lift stone and brick to the upper parts of the tower.Port, p. 211 When it came to building the Victoria and Clock towers, it was decided to dispense with external scaffolding and lift building materials up through the towers by an internal scaffolding that travelled up the structure as it was built. The scaffold and cranes were powered by steam engines.

Work on the actual building began with the laying of a foundation stone on 27 April 1840 by Barry's wife Sarah, near the north-east corner of the building. A major problem for Barry came with the appointment on 1 April 1840 of the ventilation expert Dr David Boswell Reid. Reid, whom Barry said was "...not profess to be thoroughly acquainted with the practical details of building and machinery...",Port, p. 103 would make increasing demands that affected the building's design, leading to delays in construction. By 1845, Barry was refusing to communicate with Reid except in writing. A direct result of Reid's demands was the addition of the Central Tower, designed to act as a giant chimney to draw fresh air through the building.

The House of Lords was completed in April 1847Aslet & Moore, p. 79 in the form of a double cube measuring . The British House of Commons, House of Commons was finished in 1852, where later Barry would be created a Knight Bachelor. The Elizabeth Tower, which houses the great clock and bells including Big Ben, is tall and was completed in 1858. The Victoria Tower is tall and was completed in 1860. The iron flagpole on the Victoria Tower tapers from in diameter and the iron crown on top is in diameter and above ground. The central tower is high. The building is long, covers about of land, and has over 1000 rooms. The east Thames façade is in length. Pugin later dismissed the building, saying "All Grecian, Sir, Tudor details on a classic body", the essentially symmetrical plan and river front being offensive to Pugin's taste for Gothic architecture, medieval Gothic buildings.

Before construction could commence, the site had to be Thames Embankment, embanked and cleared of the remains of the previous buildings, and various sewerage, sewers needed to be diverted. On 1 September 1837, work started on building a long coffer-dam to enclose the building site along the river. The construction of the embankment started on New Year's Day 1839.Port, p. 198 The first work consisted of the construction of a vast concrete raft to serve as the building's foundation. After the space had been excavated by hand, of concrete were laid. The site of the Victoria Tower was found to consist of quicksand, necessitating the use of deep foundation, piles. The stone selected for the exterior of the building was quarried at Anston in Yorkshire, with the core of the walls being laid in brick. To make the building as fire-proof as possible, wood was only used decoratively, rather than structurally, and extensive use was made of cast iron. The roofs of the building consist of cast iron girders covered by sheets of iron, cast iron beams were also used as joists to support the floors and extensively in the internal structures of both the clock tower and Victoria tower.

Barry and his engineer Alfred Meeson were responsible for designing scaffolding, hoist (device), hoists and crane (machine), cranes used in the construction. One of their most innovative developments was the scaffolding used to construct the three main towers. For the central tower they designed an inner rotating scaffold, surrounded by timber centring to support the masonry vault of the Central Lobby, that spans , and an external timber tower. A portable steam engine was used to lift stone and brick to the upper parts of the tower.Port, p. 211 When it came to building the Victoria and Clock towers, it was decided to dispense with external scaffolding and lift building materials up through the towers by an internal scaffolding that travelled up the structure as it was built. The scaffold and cranes were powered by steam engines.

Work on the actual building began with the laying of a foundation stone on 27 April 1840 by Barry's wife Sarah, near the north-east corner of the building. A major problem for Barry came with the appointment on 1 April 1840 of the ventilation expert Dr David Boswell Reid. Reid, whom Barry said was "...not profess to be thoroughly acquainted with the practical details of building and machinery...",Port, p. 103 would make increasing demands that affected the building's design, leading to delays in construction. By 1845, Barry was refusing to communicate with Reid except in writing. A direct result of Reid's demands was the addition of the Central Tower, designed to act as a giant chimney to draw fresh air through the building.

The House of Lords was completed in April 1847Aslet & Moore, p. 79 in the form of a double cube measuring . The British House of Commons, House of Commons was finished in 1852, where later Barry would be created a Knight Bachelor. The Elizabeth Tower, which houses the great clock and bells including Big Ben, is tall and was completed in 1858. The Victoria Tower is tall and was completed in 1860. The iron flagpole on the Victoria Tower tapers from in diameter and the iron crown on top is in diameter and above ground. The central tower is high. The building is long, covers about of land, and has over 1000 rooms. The east Thames façade is in length. Pugin later dismissed the building, saying "All Grecian, Sir, Tudor details on a classic body", the essentially symmetrical plan and river front being offensive to Pugin's taste for Gothic architecture, medieval Gothic buildings.

The plan of the finished building is built around two major axes. At the southern end of Westminster Hall, St. Stephen's porch was created as a major entrance to the building. This involved inserting a great arch with a grand staircase at the southern end of Westminster hall, which leads to the first floor where the major rooms are located. To the east of St. Stephens porch is St. Stephen's Hall, built on the surviving undercroft of St. Stephen's Chapel. To the east of this the octagonal Central Lobby (above which is the central tower), the centre of the building. North of the Central Lobby is the Commons' Corridor which leads into the square Commons' Lobby, north of which is the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons.

There are various offices and corridors to the north of the House of Commons with the clock tower terminating the northern axis of the building. South of the Central Lobby is the Peers' Corridor leading to the Peers' Lobby, south of which lies the House of Lords. South of the House of Lords in sequence are the Prince's Chamber, Royal Gallery, and Queen's Robing Room. To the north-west of the Queen's Robing Chamber is the Norman Porch, to the west of which the Royal Staircase leads down to the Royal Entrance located immediately beneath the Victoria Tower. East of the Central Lobby is the East Corridor leading to the Lower Waiting Hall, to the east of which is the Members Dining Room located in the very centre of the east front. To the north of the Members Dining Room lies the House of Commons Library, and at the northern end of the east front is the projecting Speaker's House, home of the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. To the south of the Members Dining Room lies various committee rooms followed by House of Lords Library. Projecting from the southern end of the facade is the Lord Chancellor's House, home of The Lord Chancellor.

Although Parliament gave Barry a prestigious name in architecture, it nearly finished him off. Completion of the building was very overdue; Barry had estimated it would take six years and cost £724,986 (excluding the cost of the site, embankment and furnishings). However, construction actually took 26 years, and it was also well over budget; by July 1854 the estimated cost was £2,166,846. Those pressures left Barry tired and stressed. The full Barry design was never completed; it would have enclosed New Palace Yard as an internal courtyard, and the clock tower would have been in the north-east corner, with a great gateway in the north-west corner surmounted by the Albert Tower, continuing south along the west front of Westminster Hall.

The plan of the finished building is built around two major axes. At the southern end of Westminster Hall, St. Stephen's porch was created as a major entrance to the building. This involved inserting a great arch with a grand staircase at the southern end of Westminster hall, which leads to the first floor where the major rooms are located. To the east of St. Stephens porch is St. Stephen's Hall, built on the surviving undercroft of St. Stephen's Chapel. To the east of this the octagonal Central Lobby (above which is the central tower), the centre of the building. North of the Central Lobby is the Commons' Corridor which leads into the square Commons' Lobby, north of which is the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons.

There are various offices and corridors to the north of the House of Commons with the clock tower terminating the northern axis of the building. South of the Central Lobby is the Peers' Corridor leading to the Peers' Lobby, south of which lies the House of Lords. South of the House of Lords in sequence are the Prince's Chamber, Royal Gallery, and Queen's Robing Room. To the north-west of the Queen's Robing Chamber is the Norman Porch, to the west of which the Royal Staircase leads down to the Royal Entrance located immediately beneath the Victoria Tower. East of the Central Lobby is the East Corridor leading to the Lower Waiting Hall, to the east of which is the Members Dining Room located in the very centre of the east front. To the north of the Members Dining Room lies the House of Commons Library, and at the northern end of the east front is the projecting Speaker's House, home of the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. To the south of the Members Dining Room lies various committee rooms followed by House of Lords Library. Projecting from the southern end of the facade is the Lord Chancellor's House, home of The Lord Chancellor.

Although Parliament gave Barry a prestigious name in architecture, it nearly finished him off. Completion of the building was very overdue; Barry had estimated it would take six years and cost £724,986 (excluding the cost of the site, embankment and furnishings). However, construction actually took 26 years, and it was also well over budget; by July 1854 the estimated cost was £2,166,846. Those pressures left Barry tired and stressed. The full Barry design was never completed; it would have enclosed New Palace Yard as an internal courtyard, and the clock tower would have been in the north-east corner, with a great gateway in the north-west corner surmounted by the Albert Tower, continuing south along the west front of Westminster Hall.

From onward 1837 Barry suffered from sudden bouts of illness, one of the most severe being in 1858. On 12 May 1860 after an afternoon at the Crystal Palace with Lady Barry, at his home ''The Elms'', Clapham Common, he was seized at eleven o'clock at night with difficulty in breathing and was in pain from a heart attack and died shortly after.

His funeral and interment took place at one o'clock on 22 May in Westminster Abbey,Barry, p. 342 the cortège formed at Vauxhall Bridge, there were eight pall-bearers: Charles Lock Eastlake, Sir Charles Eastlake; William Cowper-Temple, 1st Baron Mount Temple; George Parker Bidder; Sir Edward Cust, 1st Baronet; Alexander Beresford Hope; The Dean of St. Paul's Henry Hart Milman; Charles Robert Cockerell and Sir William Tite. There were several hundred mourners at the funeral service, including his five sons, (it was against custom for women to attend, so neither his widow or daughters were present), his friend Mr Wolfe, numerous members of the House of Commons and Lords, attended, several who were his former clients, about 150 members of the R.I.B.A., including: Decimus Burton, Thomas Leverton Donaldson, Benjamin Ferrey, Charles Fowler, George Godwin, Owen Jones (architect), Owen Jones, Henry Edward Kendall, John Norton (architect), John Norton, Joseph Paxton, James Pennethorne, Anthony Salvin, Sydney Smirke, Lewis Vulliamy, Matthew Digby Wyatt and Thomas Henry Wyatt. Various members of the Royal Society, Royal Academy, Institution of Civil Engineers, Society for the Encouragement of Fine Art and Society of Antiquaries were present. The funeral service was taken by the Dean of Westminster Abbey Richard Chenevix Trench.

Hardman & Co. made the monumental brass marking Barry's tomb in the nave at Westminster Abbey shows the Victoria Tower and Plan of the Palace of Westminster flanking a large Christian cross bearing representations of the Lamb of God, Paschal Lamb and the four Evangelists and on the stem are roses, leaves, a portcullis and the letter B., beneath is this inscription:

From onward 1837 Barry suffered from sudden bouts of illness, one of the most severe being in 1858. On 12 May 1860 after an afternoon at the Crystal Palace with Lady Barry, at his home ''The Elms'', Clapham Common, he was seized at eleven o'clock at night with difficulty in breathing and was in pain from a heart attack and died shortly after.

His funeral and interment took place at one o'clock on 22 May in Westminster Abbey,Barry, p. 342 the cortège formed at Vauxhall Bridge, there were eight pall-bearers: Charles Lock Eastlake, Sir Charles Eastlake; William Cowper-Temple, 1st Baron Mount Temple; George Parker Bidder; Sir Edward Cust, 1st Baronet; Alexander Beresford Hope; The Dean of St. Paul's Henry Hart Milman; Charles Robert Cockerell and Sir William Tite. There were several hundred mourners at the funeral service, including his five sons, (it was against custom for women to attend, so neither his widow or daughters were present), his friend Mr Wolfe, numerous members of the House of Commons and Lords, attended, several who were his former clients, about 150 members of the R.I.B.A., including: Decimus Burton, Thomas Leverton Donaldson, Benjamin Ferrey, Charles Fowler, George Godwin, Owen Jones (architect), Owen Jones, Henry Edward Kendall, John Norton (architect), John Norton, Joseph Paxton, James Pennethorne, Anthony Salvin, Sydney Smirke, Lewis Vulliamy, Matthew Digby Wyatt and Thomas Henry Wyatt. Various members of the Royal Society, Royal Academy, Institution of Civil Engineers, Society for the Encouragement of Fine Art and Society of Antiquaries were present. The funeral service was taken by the Dean of Westminster Abbey Richard Chenevix Trench.

Hardman & Co. made the monumental brass marking Barry's tomb in the nave at Westminster Abbey shows the Victoria Tower and Plan of the Palace of Westminster flanking a large Christian cross bearing representations of the Lamb of God, Paschal Lamb and the four Evangelists and on the stem are roses, leaves, a portcullis and the letter B., beneath is this inscription:

Biography – Britain Express

Palace of WestminsterCharles Barry & the Map Room – UK Parliament Living Heritage

Papers of Charles Barry

at the UK Parliamentary Archives * Charles Barry works

Charles Barry Fonds

McGill University Library & Archives.

Parliamentary Archives, Papers of Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860), Architect

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barry, Charles 1795 births 1860 deaths Burials at Westminster Abbey 19th-century British architects Fellows of the Royal Society Italianate architecture in the United Kingdom Historicist architects Knights Bachelor People from Westminster Architects from London Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal Royal Academicians

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

(also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsible for numerous other buildings and gardens. He is known for his major contribution to the use of Italianate architecture

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian R ...

in Britain, especially the use of the Palazzo as basis for the design of country houses, city mansions and public buildings. He also developed the Italian Renaissance garden

The Italian Renaissance garden was a new style of garden which emerged in the late 15th century at villas in Rome and Florence, inspired by classical ideals of order and beauty, and intended for the pleasure of the view of the garden and the landsc ...

style for the many gardens he designed around country houses.Bisgrove, p. 179

Background and training

Born on 23 May 1795Barry p. 4 in Bridge Street,Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

(opposite the future site of the Clock Tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another buildi ...

of the Palace of Westminster), he was the fourth son of Walter Edward Barry (died 1805), a stationer, and Frances Barry (née Maybank; died 1798). He was baptised at St Margaret's, Westminster, into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, of which he was a lifelong member. His father remarried shortly after Frances died and Barry's stepmother Sarah would bring him up.

He was educated at private schools in Homerton

Homerton ( ) is an area in London, England, in the London Borough of Hackney. It is bordered to the west by Hackney Central, to the north by Lower Clapton, in the east by Hackney Wick, Leyton and by South Hackney to the south. In 2019, it had ...

and then Aspley Guise

Aspley Guise is a village and civil parish in the west of Central Bedfordshire, England. In addition to the village of Aspley Guise itself, the civil parish also includes part of the town of Woburn Sands, the rest of which is in the City of Milto ...

, before being apprenticed to Middleton & Bailey,Brodie, Felstead, Franklin, Pinfield and Oldfield, p. 123 Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

architects and surveyors, at the age of 15. Barry exhibited drawings at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

annually from 1812 to 1815. Upon the death of his father, Barry inherited a sum of money that allowed him, after coming of age

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the change. It can be a simple legal convention or can b ...

, to undertake an extensive Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tuto ...

around the Mediterranean and Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, from 28 June 1817 to August 1820.

He visited France and, while in Paris, spent several days at the Musée du Louvre. In Rome, he sketched antiquities, sculptures and paintings at the Vatican Museums

The Vatican Museums ( it, Musei Vaticani; la, Musea Vaticana) are the public museums of the Vatican City. They display works from the immense collection amassed by the Catholic Church and the papacy throughout the centuries, including several of ...

and other galleries, before carrying on to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried ...

, Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

and then Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

. While in Italy, Barry met Charles Lock Eastlake, an architect, William Kinnaird and Francis Johnson (later a professor at Haileybury and Imperial Service College) and Thomas Leverton Donaldson.

With these gentlemen he visited Greece, where their itinerary covered Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, which they left on 25 June 1818, Mount Parnassus, Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

, Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born ...

, then the Cyclades, including Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island are ...

, then Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, where Barry greatly admired the magnificence of Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

. From Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

he visited the Troad, Assos, Pergamon and back to Smyrna. In Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, he met David Baillie, who was taken with Barry's sketches and offered to pay him £200 a year plus any expenses to accompany him to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

in return for Barry's drawings of the countries they visited. Middle East sites they visited included Dendera

Dendera ( ar, دَنْدَرة ''Dandarah''; grc, Τεντυρις or Τεντυρα; Bohairic cop, ⲛⲓⲧⲉⲛⲧⲱⲣⲓ, translit=Nitentōri; Sahidic cop, ⲛⲓⲧⲛⲧⲱⲣⲉ, translit=Nitntōre), also spelled ''Denderah'', ancient ...

, the Temple of Edfu and Philae – it was at the last of these three that he met his future client, William John Bankes, on 13 January 1819 – then Thebes, Luxor

Luxor ( ar, الأقصر, al-ʾuqṣur, lit=the palaces) is a modern city in Upper (southern) Egypt which includes the site of the Ancient Egyptian city of ''Thebes''.

Luxor has frequently been characterized as the "world's greatest open-a ...

and Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (, which was originally derived from ar, خورنق ''Khurnaq'' "fortified village"), comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Construct ...

. Then, back to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

and Giza

Giza (; sometimes spelled ''Gizah'' arz, الجيزة ' ) is the second-largest city in Egypt after Cairo and fourth-largest city in Africa after Kinshasa, Lagos and Cairo. It is the capital of Giza Governorate with a total population of 9.2 ...

with its pyramids.Barry, p. 36

Continuing through the Middle East, the major sites and cities visited were Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

, the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

, then Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital o ...

, Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

, Jerash, Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

and Palmyra, then on to Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

.

On 18 June 1819, Barry parted from Baillie at Tripoli, Lebanon. Over this time, Barry created more than 500 sketches. Barry then travelled on to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus (; grc, Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός ''Halikarnāssós'' or ''Alikarnāssós''; tr, Halikarnas; Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. It was located i ...

, Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

and Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

from where he sailed on 16 August 1819 for Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

.Barry, p. 43

Barry then sailed from Malta to Syracuse, Sicily

Syracuse ( ; it, Siracusa ; scn, Sarausa ), ; grc-att, wikt:Συράκουσαι, Συράκουσαι, Syrákousai, ; grc-dor, wikt:Συράκοσαι, Συράκοσαι, Syrā́kosai, ; grc-x-medieval, Συρακοῦσαι, Syrakoûs ...

, then Italy and back through France. His travels in Italy exposed him to Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of Ancient Greece, ancient Greek and ...

and after arriving in Rome in January 1820, he met architect John Lewis Wolfe

John Lewis Wolfe (10 April 1798 - 6 October 1881) was an English architect, artist and stockbroker. He had a longtime friendship with fellow architect Charles Barry, who was inspired to become an architect by Wolfe.

Early life and education

Joh ...

, who inspired Barry himself to become an architect. Their friendship continued until Barry died. The building that inspired Barry's admiration for Italian architecture was the Palazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance List of palaces in Italy#Rome, palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and cur ...

. Over the following months, he and Wolfe together studied the architecture of Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a th ...

, Venice, Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Northern Italy, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and the ...

and Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

, where the Palazzo Strozzi greatly impressed him.

Early career

While in Rome he had met Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, through whom he met

While in Rome he had met Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, through whom he met Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland

Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland of Holland, and 3rd Baron Holland of Foxley PC (21 November 1773 – 22 October 1840), was an English politician and a major figure in Whig politics in the early 19th century. A grandson of Henry F ...

, and his wife, Elizabeth Fox, Baroness Holland

Elizabeth Vassall Fox, Baroness Holland (1771 – London, November 1845) was an English political hostess and the wife of Whig politician Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland. With her husband, and after his death, she hosted political and litera ...

. Their London home, Holland House

Holland House, originally known as Cope Castle, was an early Jacobean country house in Kensington, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, was the centre of the Whig Party. Barry remained a lifelong supporter of the Liberal Party,Barry, p. 337 the successor to the Whig Party. Barry was invited to the gatherings at the house, and there met many of the prominent members of the group; this led to many of his subsequent commissions. Barry set up his home and office in Ely Place

Ely Place is a gated road of multi-storey terraces at the southern tip of the London Borough of Camden in London, England. It hosts a 1773-rebuilt public house, Ye Olde Mitre, of Tudor origin and is adjacent to Hatton Garden.

It is privatel ...

in 1821. In 1827 he moved to 27 Foley Place, then in 1842 he moved to 32 Great George Street and finally to The Elms, Clapham Common. Now 29 Clapham Common Northside, the Georgian house of five bays and three stories was designed by Samuel Pepys Cockerell as his own home.

Probably thanks to his fiancée's friendship with John Soane,Colvin, p. 90 Barry was recommended to the Church Building Commissioners, and was able to obtain his first major commissions building churches for them. These were in the Gothic Revival architecture

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

style, including two in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, St Matthew, Campfield, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

(1821–22), and All Saints' Church, Whitefield (or Stand) (1822–25). Barry designed three churches for the Commissioners in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

: Holy Trinity, St John's and St Paul's, all in the Gothic style and built between 1826 and 1828.

Two further Gothic churches in Lancashire, not for the Commissioners followed in 1824:

Two further Gothic churches in Lancashire, not for the Commissioners followed in 1824: St Saviour's Church, Ringley

St Saviour's Church is in Ringley, Kearsley, near Bolton, Greater Manchester, England. It is an active Anglican parish church in the deanery of Bolton, the archdeaconry of Bolton and the diocese of Manchester. Its benefice is united with those ...

, partially rebuilt in 1851–54, and Barry's neglected Welsh Baptist Chapel

The Upper Brook Street Chapel, also known as the Islamic Academy, the Unitarian Chapel and the Welsh Baptist Chapel, is a former chapel with an attached Sunday School on the east side of Upper Brook Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Greater Manchester ...

, on Upper Brook Street (1837–39) in Manchester (and owned by the City Council), long open to the elements and at serious risk after its roof was removed in late 2005, the building was converted to private apartments in 2014–17. His final church for the Commissioners' was the Gothic St Peter's Church, Brighton

St Peter's Church is a church in Brighton in the English city of Brighton and Hove. It is near the centre of the city, on an island between two major roads, the A23 London Road and A270 Lewes Road. Built from 1824–28 to a design by Sir Charles ...

(1824–28), which he won in a design competition on 4 August 1823 and was his first building to win acclaim.

The next church he designed was St Andrew's Hove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th cen ...

, East Sussex, in Waterloo Street, Brunswick, (1827–28); the plan of the building is in line with Georgian architecture

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1714 and 1830. It is named after the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover—George I, George II, Georg ...

, though stylistically the Italianate style was used, the only classical church Barry designed that was actually built. The Gothic Hurstpierpoint

Hurstpierpoint is a village in West Sussex, England, southwest of Burgess Hill, and west of Hassocks railway station. It sits in the civil parish of Hurstpierpoint and Sayers Common which has an area of 2029.88 ha and a population of ...

church (1843–45), with its tower and spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires are ...

, unlike his earlier churches was much closer to the Cambridge Camden Society's approach to church design. According to his son Alfred, Barry later disowned these early church designs of the 1820s and wished he could destroy them.

His first major civil commission came when he won a competition to design the new Royal Manchester Institution (1824–1835) for the promotion of literature, science and arts (now part of the Manchester Art Gallery

Manchester Art Gallery, formerly Manchester City Art Gallery, is a publicly owned art museum on Mosley Street in Manchester city centre. The main gallery premises were built for a learned society in 1823 and today its collection occupies three c ...

), in Greek revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but ...

style, the only public building by Barry in that style. Also in north-west England, he designed Buile Hill House (1825) in Salford this is the only known house where Barry used Greek revival architecture. The Royal Sussex County Hospital was erected to Barry's design (1828) in a very plain classical style.

Thomas Attree's villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

, Queen's Park, Brighton, the only one to be built of a series of villas designed for the area by Barry and the Pepper Pot (1830), whose original function was a water tower

A water tower is an elevated structure supporting a water tank constructed at a height sufficient to pressurize a water distribution system, distribution system for potable water, and to provide emergency storage for fire protection. Water towe ...

for the development. In 1831, he entered the competition for the design of Birmingham Town Hall

Birmingham Town Hall is a concert hall and venue for popular assemblies opened in 1834 and situated in Victoria Square, Birmingham, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

The hall underwent a major renovation between 2002 and 2007. It no ...

, the design was based on an Ancient Greek temple

Greek temples ( grc, ναός, naós, dwelling, semantically distinct from Latin , "temple") were structures built to house deity statues within Greek sanctuaries in ancient Greek religion. The temple interiors did not serve as meeting places, ...

of the Doric order, but it failed to win the competition.

The marked preference for Italian architecture, which he acquired during his travels showed itself in various important undertakings of his earlier years, the first significant example being the Travellers Club, in Pall Mall, built in 1832, as with all his urban commissions in this style the design was astylar Astylar (from Gr. ''ἀ-'', privative, and ''στῦλος'', a column) is an architectural term given to a class of design in which neither columns nor pilasters are used for decorative purposes; thus the Riccardi and Strozzi palaces in Florence a ...

. He designed the Gothic King Edward's School, New Street, Birmingham (1833–37), demolished 1936, it was during the erection of the school that Barry first met Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, he helped Barry design the interiors of the building.

His last work in Manchester was the Italianate Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39), this is now part of Manchester Art Gallery. From 1835–37, he rebuilt

His last work in Manchester was the Italianate Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39), this is now part of Manchester Art Gallery. From 1835–37, he rebuilt Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. The ...

, in Lincoln's Inn Fields, Westminster, he preserved the Ionic portico from the earlier building (1806–13) designed by George Dance the Younger, the building has been further extended (1887–88) and (1937). In 1837, he won the competition to design the Reform Club, Pall Mall, London, which is one of his finest Italianate public buildings, notable for its double height central saloon with glazed roof. His favourite building in Rome, the Farnese Palace, influenced the design.

Country house work

country houses

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

. His first major commission was the transformation of Henry Holland's Trentham Hall

The Trentham Estate, in the village of Trentham, is a visitor attraction located on the southern fringe of the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

History

The estate was first recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086. At th ...

in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

, between 1834 and 1840. It was remodelled in the Italianate style with a large tower (a feature Barry often included in his country houses). Barry also designed the Italianate gardens, with parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the part of ...

s and fountains. Largely demolished in 1912, only a small portion of the house, consisting of the porte-cochère with a curving corridor, and the stables, are still standing, although the gardens are undergoing a restoration. Additionally, the belvedere Belvedere (from Italian, meaning "beautiful sight") may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Belvedere, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

Africa

*Belvedere (Casablanca), a neighborhood in Casablanca, Morocco

*Belvedere, Harare, Zim ...

from the top of the tower survives as a folly at Sandon Hall

Sandon Hall is a 19th-century country mansion, the seat of the Earl of Harrowby, at Sandon, Staffordshire, northeast of Stafford. It is a Grade II* listed building set in of parkland.

Early manorial history

Before the Norman Conquest, Sandon w ...

.

Between 1834 and 1838, at Bowood House

Bowood is a Grade I listed Georgian country house in Wiltshire, England, that has been owned for more than 250 years by the Fitzmaurice family. The house, with interiors by Robert Adam, stands in extensive grounds which include a garden designed ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, owned by Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, Barry added the tower, made alterations to the gardens, and designed the Italianate entrance lodge. For the same client, he designed the Lansdowne Monument

The Lansdowne Monument, also known as the Cherhill Monument, near Cherhill in Wiltshire, England, is a 38-metre (125 foot) stone obelisk erected in 1845 by the 3rd Marquis of Lansdowne to the designs of Sir Charles Barry to commemorate his ancest ...

in 1845. Walton House in Walton-on-Thames followed in 1835–39. Again Barry used the Italianate style, with a three-storey tower over the entrance porte-cochère (which was demolished 1973). Then, from 1835 to 1838, he remodelled Sir Roger Pratt's Kingston Lacy

Kingston Lacy is a country house and estate near Wimborne Minster, Dorset, England. It was for many years the family seat of the Bankes family who lived nearby at Corfe Castle until its destruction in the English Civil War after its incumbent ow ...

, with the exterior being re-clad in stone. The interiors were also Barry's work.

Highclere Castle, Hampshire, with its large tower, was remodelled between about 1842 and 1850, in

Highclere Castle, Hampshire, with its large tower, was remodelled between about 1842 and 1850, in Elizabethan style

Elizabethan architecture refers to buildings of a certain style constructed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland from 1558–1603. Historically, the era sits between the long era of the dominant architectural style o ...

, for Henry Herbert, 3rd Earl of Carnarvon

Henry John George Herbert, 3rd Earl of Carnarvon, FRS (8 June 1800 – 10 December 1849), styled Lord Porchester from 1811 to 1833, was a British writer, traveller, nobleman, and politician.

Background and education

Herbert was born in London ...

. The building was completely altered externally, with the plain Georgian structure being virtually rebuilt. However, little of the interior is by Barry, because his patron died in 1849 and Thomas Allom

Thomas Allom (13 March 1804 – 21 October 1872) was an English architect, artist, and topographical illustrator. He was a founding member of what became the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). He designed many buildings in London, in ...

completed the work in 1861. At Duncombe Park

Duncombe Park is the seat of the Duncombe family who previously held the Earldom of Feversham. The title became extinct on the death of the 3rd Earl in 1963, since when the family have continued to hold the title Baron Feversham. The park is si ...

, Yorkshire, Barry designed new wings, which were added between in 1843 and 1846 in the English Baroque style of the main block. At Harewood House

Harewood House ( , ) is a country house in Harewood, West Yorkshire, England. Designed by architects John Carr and Robert Adam, it was built, between 1759 and 1771, for Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, a wealthy West Indian plantation a ...

he remodelled the John Carr John Carr may refer to:

Politicians

*John Carr (Indiana politician) (1793–1845), American politician from Indiana

*John Carr (Australian politician, born 1819) (1819–1913), member of the South Australian House of Assembly, 1865–1884

* John H ...

exterior between 1843 and 1850, adding an extra floor to the end pavilions, and replacing the portico on the south front with Corinthian pilasters. Some of the Robert Adam interiors were remodelled, with the dining room being entirely by Barry, and he created the formal terraces and parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the part of ...

s surrounding the house.

Between 1844 and 1848, Barry remodelled Dunrobin Castle

Dunrobin Castle (mostly 1835–1845 — present) is a stately home in Sutherland, in the Highland area of Scotland, as well as the family seat of the Earl of Sutherland and the Clan Sutherland. It is located north of Golspie and approximatel ...

, Sutherland

Sutherland ( gd, Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. Its county town is Dornoch. Sutherland borders Caithness and Moray Firth to the east, Ross-shire and Cromartyshire (later ...

, Scotland, in Scots Baronial Style

Scottish baronial or Scots baronial is an architectural style of 19th century Gothic Revival which revived the forms and ornaments of historical architecture of Scotland in the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Reminiscent of Sco ...

, for George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland for whom he had remodelled Trentham Hall. Due to a fire in the early 20th century, little of Barry's interiors survive at Dunrobin, but the gardens, with their fountains and parterres, are also by Barry. Canford Manor, Dorset, was extended in a Tudor Gothic style between 1848 and 1852, including a large entrance tower. The most unusual interior is the Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

porch, built to house Assyrian sculptures from the eponymous palace, decorated with Assyrian motifs.

James Paine's

James Paine's Shrubland Park

Shrubland Hall, Coddenham, Suffolk, is a historic English country house with planned gardens in Suffolk, England, built in the 1770s.

The Hall was used as a health clinic in the second half of the 20th century and briefly reopened as a hotel, ...

was remodelled between 1849 and 1854, including an Italianate tower and entrance porch, a lower hall with Corinthian columns and glass domes, and impressive formal gardens based on Italian Renaissance garden

The Italian Renaissance garden was a new style of garden which emerged in the late 15th century at villas in Rome and Florence, inspired by classical ideals of order and beauty, and intended for the pleasure of the view of the garden and the landsc ...

s. The gardens included a -high series of terraces linked by a grand flight of steps, with an open temple structure at the top. Originally there were cascades of water either side of the staircase. The main terrace is at the centre of a string of gardens nearly in length.

Between 1850 and 1852, Barry remodelled Gawthorpe Hall, an Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

house situated south-east of the small town of Padiham

Padiham ( ) is a town and civil parish on the River Calder, about west of Burnley, Lancashire, England. It forms part of the Borough of Burnley. Originally by the River Calder, it is edged by the foothills of Pendle Hill to the north-west ...

, in the borough of Burnley

Burnley () is a town and the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Burnley in Lancashire, England, with a 2001 population of 73,021. It is north of Manchester and east of Preston, at the confluence of the River Calder and River Bru ...

, Lancashire. It was originally a pele tower

Peel towers (also spelt pele) are small fortified keeps or tower houses, built along the English and Scottish borders in the Scottish Marches and North of England, mainly between the mid-14th century and about 1600. They were free-standing ...

, built in the 14th century as a defence against the invading Scots. Around 1600, a Jacobean mansion had been dovetailed around the pele, but today's hall is re-design of the house, using the original Elizabethan style.

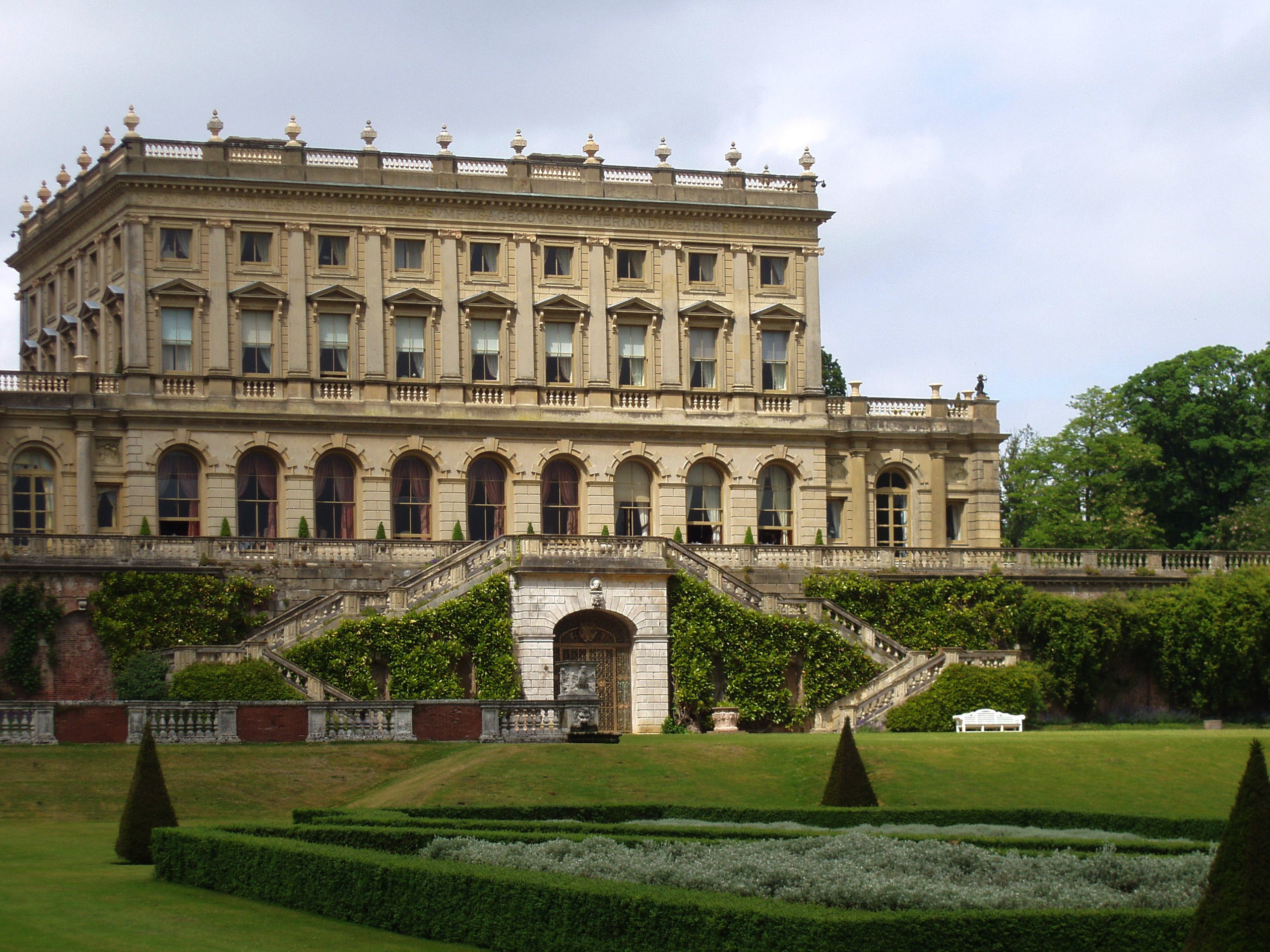

Cliveden House

Cliveden (pronounced ) is an English country house and estate in the care of the National Trust in Buckinghamshire, on the border with Berkshire. The Italianate mansion, also known as Cliveden House, crowns an outlying ridge of the Chiltern H ...

, which had been the seat of the Earl of Orkney from 1696 till 1824. Barry's remodelling was again on behalf of the 2nd Duke of Sutherland

Sutherland ( gd, Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. Its county town is Dornoch. Sutherland borders Caithness and Moray Firth to the east, Ross-shire and Cromartyshire (later ...

. After the previous building was burnt down (1850–51), Barry built a new central block in the Italianate Style, rising to three floors, the lowest of which have arch headed windows, and the upper two floors have giant Ionic order, Ionic pilasters. He also designed the parterres below the house. Little of Barry's interior design survived later remodelling.

Later urban work

Barry remodelled Trafalgar Square (1840–45) he designed the north terrace with the steps at either end, and the sloping walls on the east and west of the square, the two fountain basins are also to Barry's design, although Edwin Lutyens re-designed the actual fountains (1939).Bradley & Pevsner, pp. 257–258

Barry was commissioned to design (1840–42) the facade of Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville prison, that was designed by Joshua Jebb, he added a stuccoed Italianate pilastered frontage to Caledonian Road. The (Old) Treasury (Now Cabinet Office) Whitehall by John Soane, built (1824–26) was virtually rebuilt by Barry (1844–47). It consists of 23 bays with a giant Corinthian order over a Rustication (architecture), rusticated ground floor, the five bays at each end project slightly from the facade.

Bridgewater House, Westminster, London (1845–64) for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, in a grand Italianate style. The structure was complete by 1848, but interior decoration was only finished by 1864. The main (south) front is 144 feet long, of nine bays in more massive version of his earlier Reform Club, the garden (west) front is of seven bays. The interiors are intact apart from the north wing which was bombed in The Blitz. The main interior is the central Saloon, a roofed courtyard of two storeys, of three by five bays of arches on each floor, the walls are lined with scagliola, the coved ceiling is glazed and the centre has three glazed saucer domes. The decoration of the major rooms is not the work of Barry.

Barry remodelled Trafalgar Square (1840–45) he designed the north terrace with the steps at either end, and the sloping walls on the east and west of the square, the two fountain basins are also to Barry's design, although Edwin Lutyens re-designed the actual fountains (1939).Bradley & Pevsner, pp. 257–258

Barry was commissioned to design (1840–42) the facade of Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville prison, that was designed by Joshua Jebb, he added a stuccoed Italianate pilastered frontage to Caledonian Road. The (Old) Treasury (Now Cabinet Office) Whitehall by John Soane, built (1824–26) was virtually rebuilt by Barry (1844–47). It consists of 23 bays with a giant Corinthian order over a Rustication (architecture), rusticated ground floor, the five bays at each end project slightly from the facade.

Bridgewater House, Westminster, London (1845–64) for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, in a grand Italianate style. The structure was complete by 1848, but interior decoration was only finished by 1864. The main (south) front is 144 feet long, of nine bays in more massive version of his earlier Reform Club, the garden (west) front is of seven bays. The interiors are intact apart from the north wing which was bombed in The Blitz. The main interior is the central Saloon, a roofed courtyard of two storeys, of three by five bays of arches on each floor, the walls are lined with scagliola, the coved ceiling is glazed and the centre has three glazed saucer domes. The decoration of the major rooms is not the work of Barry.

The last major commission of Barry's was Halifax Town Hall (1859–62), in a North Italian Cinquecento style, and a grand tower with spire, the interior includes a central hall similar to that at Bridgewater House, the building was completed after Barry's death by his son Edward Middleton Barry.

Completed after Barry's death in 1863 was the classical, John Josiah Guest, Guest Memorial Reading Room and Library in Dowlais, Wales.

The most significant of Barry's designs that were not carried out included, his proposed Law Courts (1840–41), that if built would have covered Lincoln's Inn Fields with a large Greek Revival building, this rectangular building would have been over three hundred by four hundred feet, in a Greek Doric style, there would have been octastyle porticoes in the middle of the shorter sides and hexastyle porticoes on the longer sides, leading to a large central hall that would have been surrounded by twelve court rooms that in turn were surrounded by the ancillary facilities. Later was his General Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements, that were exhibited in 1857. This comprehensive scheme was for the redevelopment of much of Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade, the embankment of the River Thames on both sides of the river in the areas to the north and south of the Palace of Westminster, this would eventual be partially realised as the Victoria Embankment and Albert Embankment, three new bridges across the Thames, a vast Hotel where Charing Cross railway station was later built, the enlargement of the National Gallery (Barry's son Edward would later extend the Gallery) and new buildings around Trafalgar Square and along the new embankments and the recently created Victoria Street. There were also several new roads proposed on both sides of the Thames. The largest of the proposed buildings would have been even larger than the Palace of Westminster, this was the Government Offices, this vast building would have covered the area stretching from horse Guards Parade across Downing Street and the sites of the future Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Government Offices Great George Street, HM Treasury on Whitehall up to Parliament Square. It would have had a vast glass-roofed hall, 320 by 150 feet, at the centre of the building. The plan was to house all government departments apart from the Admiralty in the building. The building would have been in a Classical style incorporating Barry's existing Treasury building.

The last major commission of Barry's was Halifax Town Hall (1859–62), in a North Italian Cinquecento style, and a grand tower with spire, the interior includes a central hall similar to that at Bridgewater House, the building was completed after Barry's death by his son Edward Middleton Barry.

Completed after Barry's death in 1863 was the classical, John Josiah Guest, Guest Memorial Reading Room and Library in Dowlais, Wales.

The most significant of Barry's designs that were not carried out included, his proposed Law Courts (1840–41), that if built would have covered Lincoln's Inn Fields with a large Greek Revival building, this rectangular building would have been over three hundred by four hundred feet, in a Greek Doric style, there would have been octastyle porticoes in the middle of the shorter sides and hexastyle porticoes on the longer sides, leading to a large central hall that would have been surrounded by twelve court rooms that in turn were surrounded by the ancillary facilities. Later was his General Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements, that were exhibited in 1857. This comprehensive scheme was for the redevelopment of much of Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade, the embankment of the River Thames on both sides of the river in the areas to the north and south of the Palace of Westminster, this would eventual be partially realised as the Victoria Embankment and Albert Embankment, three new bridges across the Thames, a vast Hotel where Charing Cross railway station was later built, the enlargement of the National Gallery (Barry's son Edward would later extend the Gallery) and new buildings around Trafalgar Square and along the new embankments and the recently created Victoria Street. There were also several new roads proposed on both sides of the Thames. The largest of the proposed buildings would have been even larger than the Palace of Westminster, this was the Government Offices, this vast building would have covered the area stretching from horse Guards Parade across Downing Street and the sites of the future Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Government Offices Great George Street, HM Treasury on Whitehall up to Parliament Square. It would have had a vast glass-roofed hall, 320 by 150 feet, at the centre of the building. The plan was to house all government departments apart from the Admiralty in the building. The building would have been in a Classical style incorporating Barry's existing Treasury building.

Houses of Parliament