Charing Cross on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of Northumberland Avenue, running down to a wharf by the river. It was an Augustinian house, tied to a mother house at Roncesvalles in the Pyrenees. The house and lands were seized for the king in 1379, under a statute "for the forfeiture of the lands of schismatic aliens". Protracted legal action returned some rights to the prior, but in 1414, Henry V suppressed the 'alien' houses. The priory fell into a long decline owing to lack of money and arguments regarding the collection of tithes with the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. In 1541, religious artefacts were removed to St Margaret's, and the chapel was adapted as a private house; its almshouse were sequestered to the Royal Palace.''The chapel and hospital of St. Mary Rounceval''

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of Northumberland Avenue, running down to a wharf by the river. It was an Augustinian house, tied to a mother house at Roncesvalles in the Pyrenees. The house and lands were seized for the king in 1379, under a statute "for the forfeiture of the lands of schismatic aliens". Protracted legal action returned some rights to the prior, but in 1414, Henry V suppressed the 'alien' houses. The priory fell into a long decline owing to lack of money and arguments regarding the collection of tithes with the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. In 1541, religious artefacts were removed to St Margaret's, and the chapel was adapted as a private house; its almshouse were sequestered to the Royal Palace.''The chapel and hospital of St. Mary Rounceval''

'' Survey of London'': volume 18: St Martin-in-the-Fields II: The Strand (1937), pp. 1–9. Retrieved 14 February 2009 In 1608–09, the Earl of Northampton built Northumberland House on the eastern portion of the property. In June 1874, the whole of the duke's property at Charing Cross was purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works for the formation of Northumberland Avenue.

The frontage of the Rounceval property caused the narrowing at the end of the Whitehall entry to Charing Cross, and formed the section of Whitehall formerly known as Charing Cross, until road widening in the 1930s caused the rebuilding of the south side of the street, creating the current wide thoroughfare.

In 1608–09, the Earl of Northampton built Northumberland House on the eastern portion of the property. In June 1874, the whole of the duke's property at Charing Cross was purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works for the formation of Northumberland Avenue.

The frontage of the Rounceval property caused the narrowing at the end of the Whitehall entry to Charing Cross, and formed the section of Whitehall formerly known as Charing Cross, until road widening in the 1930s caused the rebuilding of the south side of the street, creating the current wide thoroughfare.

''Old and New London'': Volume 3 (1878), pp. 123–134. accessed: 13 February 2009

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the English Civil War, becoming the subject of a popular Royalist ballad:

At

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the English Civil War, becoming the subject of a popular Royalist ballad:

At  A prominent

A prominent

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the Strand with the Charing Cross Hotel. In 1865, a replacement cross was commissioned from E. M. Barry by the South Eastern Railway as the centrepiece of the station forecourt. It is not a replica, being of an ornate

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the Strand with the Charing Cross Hotel. In 1865, a replacement cross was commissioned from E. M. Barry by the South Eastern Railway as the centrepiece of the station forecourt. It is not a replica, being of an ornate

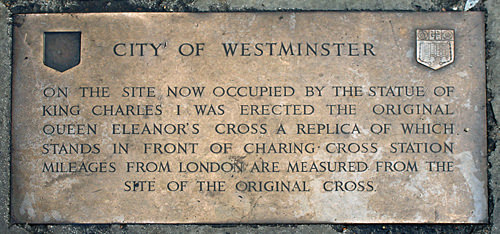

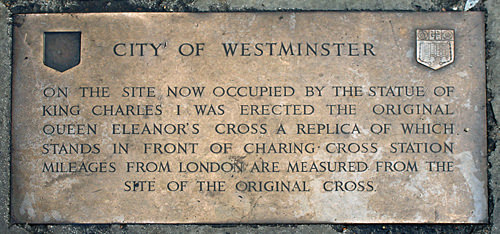

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose.

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose.

''Charing Cross Bridge'' in London from Claude Monet, in YOUR CITY AT THE THYSSEN, a Thyssen Museum project on Flickr

*'The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross', Survey of London: volume 16: St Martin-in-the-Fields I: Charing Cross (1935), pp. 258–268. URL

The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross , British History Online

Retrieved 6 March 2014. {{Authority control Areas of London Districts of the City of Westminster Kilometre-zero markers Monuments and memorials in London Execution sites in England London crime history

Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction of ...

; the Strand leading to the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

; Northumberland Avenue leading to the Thames Embankment; Whitehall leading to Parliament Square; The Mall leading to Admiralty Arch and Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

; and two short roads leading to Pall Mall. The name also commonly refers to the Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross at Charing Cross station.

A bronze equestrian statue of Charles I, erected in 1675, stands on a high plinth, situated roughly where a medieval monumental cross had previously stood for 353 years (since its construction in 1294) until destroyed in 1647 by Cromwell and his revolutionary government. The famously beheaded King, appearing ascendant, is the work of French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur.

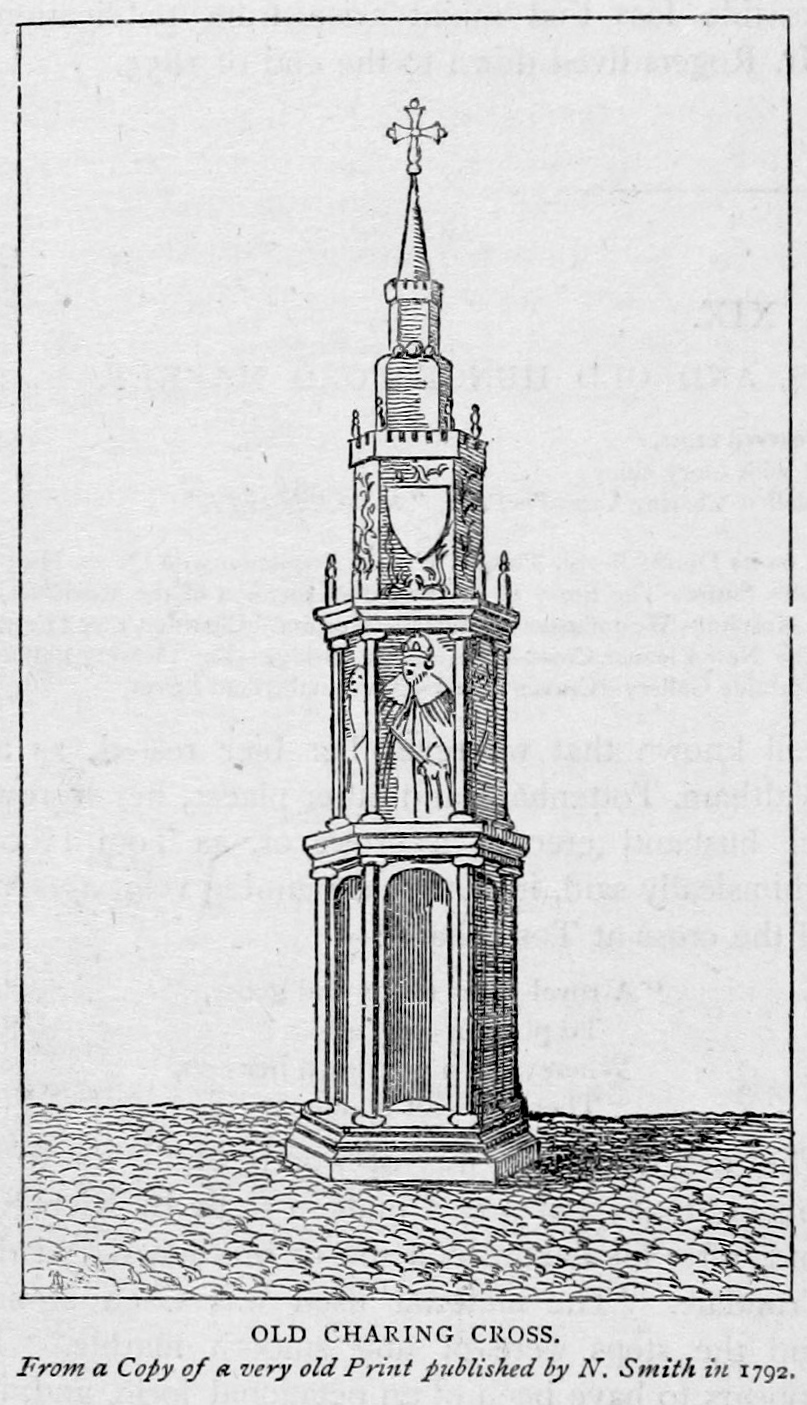

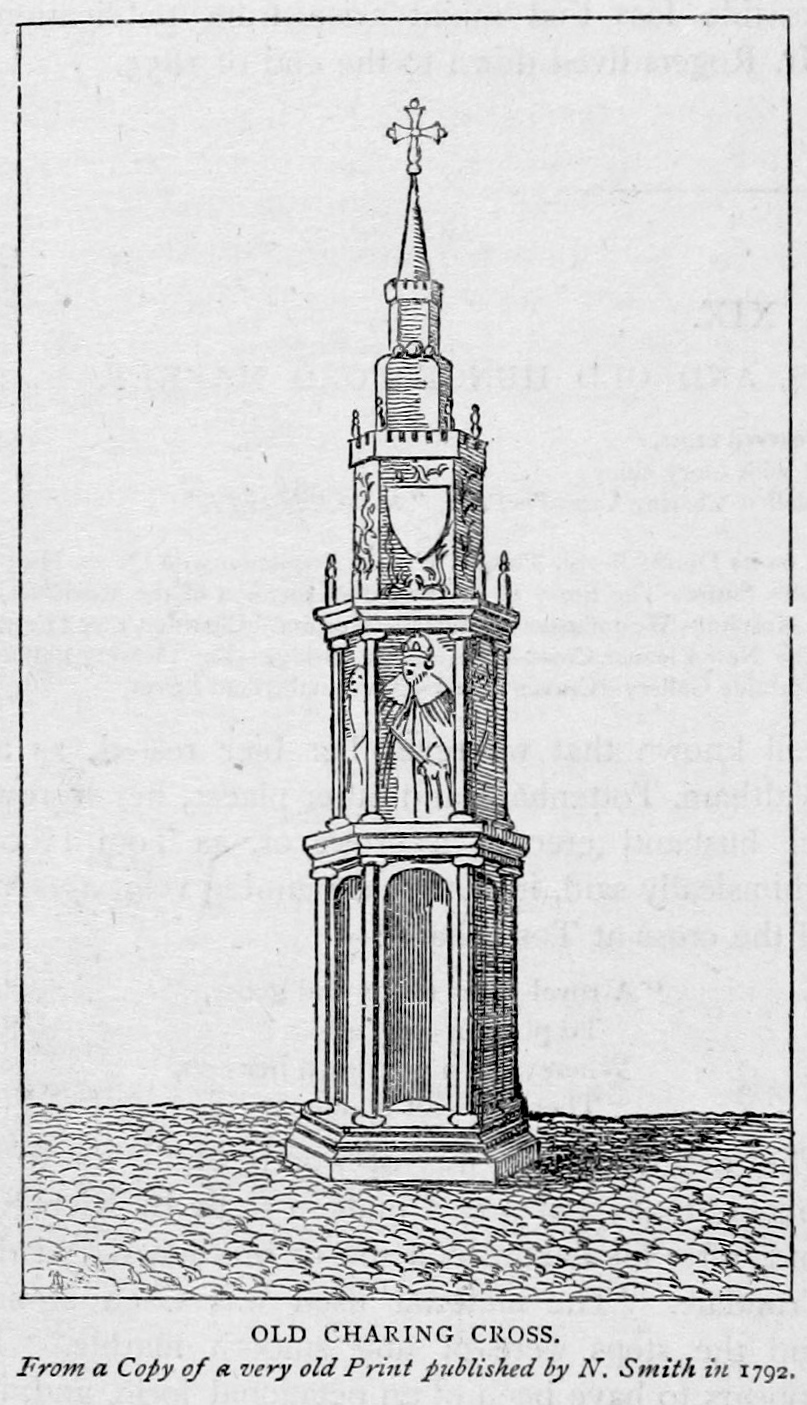

The aforementioned eponymous monument, the "Charing Cross", was the largest and most ornate instance of a chain of medieval Eleanor cross

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England. King Edward I had them built between 1291 and about 1295 in memory of his beloved wi ...

es running from Lincoln to this location. It was a landmark for many centuries of the hamlet of Charing, Westminster, which later gave way to government property; a little of The Strand; and Trafalgar Square. The cross in its various historical forms has also lent its name to its locality, and especially Charing Cross Station. On the forecourt of this terminus station stands the ornate Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross, a taller emulation of the original, and built to mark the station's opening in 1864 – at the height and in the epicentre of the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

– after the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

's rebuilding and before Westminster Cathedral's construction.

Charing Cross is marked on contemporary maps as a road junction, though it is also a thoroughfare in postal addresses: Drummonds Bank, on the corner with The Mall, retains the address 49 Charing Cross and 1-4 Charing Cross continues to exist. The name previously applied to the whole stretch of road between Great Scotland Yard and Trafalgar Square, but since 1 January 1931 most of this section of road has been designated part of the 'Whitehall' thoroughfare. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and is now the point from which distances from London are measured.

History

Location and etymology

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

word ''cierring'', a river bend, in this case thus meaning: in the Thames.

The suffix "Cross" refers to the Eleanor cross

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England. King Edward I had them built between 1291 and about 1295 in memory of his beloved wi ...

made during 1291–94 by order of King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

as a memorial to his wife, Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I, whom she married as part of a political deal to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony.

The marriage was known to be particularly close, and ...

. At the time, this place comprised little more than wayside cottages serving the Royal Mews in the northern area of today's Trafalgar Square, and built specifically for the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

(today much of the east side of Whitehall). A debunked folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

ran that the name is a corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

of ''chère reine'' ("dear queen" in French), but the name pre-dates Eleanor's death by at least a hundred years. A variant form in the hazy Middle English orthography of the late fourteenth century is ''Cherryngescrouche''.

The stone cross was the work of the medieval sculptor, Alexander of Abingdon

Alexander of Abingdon, also known as Alexander Imaginator or Alexander le Imagineur (i.e. "the image-maker"), was one of the leading sculptors of England around 1300.

Life

Alexander of Abingdon is assumed to have been from Abingdon, Berksh ...

. It was destroyed in 1647 on the orders of the purely Parliamentarian phase of the Long Parliament or Oliver Cromwell himself in the Civil War. A -high stone sculpture

A stone sculpture is an object made of stone which has been shaped, usually by carving, or assembled to form a visually interesting three-dimensional shape. Stone is more durable than most alternative materials, making it especially important in ...

in front of Charing Cross railway station, erected in 1865, is a reimagining of the medieval cross, on a larger scale, more ornate, and not on the original site. It was designed by the architect E. M. Barry and carved by Thomas Earp Thomas Earp may refer to:

* Thomas Earp (politician)

* Thomas Earp (sculptor)

Thomas Earp (1828–1893) was a British sculptor and architectural carver who was active in the late 19th century. His best known work is his 1863 reproduction of t ...

of Lambeth out of Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

, Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market tow ...

stone (a fine sandstone) and Aberdeen granite

Aberdeen is one of the most prosperous cities in Scotland owing to the variety and importance of its chief industries. Traditionally Aberdeen was home to fishing, textile mills, ship building and paper making. These industries have mostly gone a ...

; and it stands 222 yards (203 metres) to the north-east of the original cross, focal to the station forecourt, facing the Strand.

Since 1675 the site of the cross has been occupied by a statue of King Charles I mounted on a horse. The site is recognised by modern convention as the centre of London for the purpose of indicating distances (whether geodesically or by road network) in preference to other measurement points (such as St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

which remains as the root of the English and Welsh part of the Great Britain road numbering scheme). Charing Cross is marked on modern maps as a road junction, and was used in street numbering for today's section of Whitehall between Great Scotland Yard and Trafalgar Square. Since 1 January 1931 this segment has more logically and officially become the northern end of Whitehall.

The rebuilding of a monument to resemble the one lost under Cromwell's low church Britain took place in 1864 in Britain's main era of medieval revivalism. The next year the memorial was completed and Cardinal Wiseman died, the first Archbishop of Westminster

The Archbishop of Westminster heads the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster, in England. The incumbent is the metropolitan of the Province of Westminster, chief metropolitan of England and Wales and, as a matter of custom, is elected presid ...

, having been appointed such in 1850, with many Anglican churches also having restored or re-created their medieval ornamentations by the end of the century. By this time England was the epicentre of the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

.N. Yates, ''Liturgical Space: Christian Worship and Church Buildings in Western Europe 1500-2000'' (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008), p. 114, It was intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with a re-awakening of "High Church" or Anglo-Catholic self-belief (and by the Catholic convert Augustus Welby Pugin) concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism.

The cross, having been revived, gave its name to a railway station, a tube station, a police station, a hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

, a hotel, a theatre, and a music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Bri ...

(which had lain beneath the arches of the railway station). Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction of ...

, the main route from the north (which became the east side of Trafalgar Square), was named after the railway station, itself a major destination for traffic, rather than after the original cross.

St Mary Rounceval

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of Northumberland Avenue, running down to a wharf by the river. It was an Augustinian house, tied to a mother house at Roncesvalles in the Pyrenees. The house and lands were seized for the king in 1379, under a statute "for the forfeiture of the lands of schismatic aliens". Protracted legal action returned some rights to the prior, but in 1414, Henry V suppressed the 'alien' houses. The priory fell into a long decline owing to lack of money and arguments regarding the collection of tithes with the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. In 1541, religious artefacts were removed to St Margaret's, and the chapel was adapted as a private house; its almshouse were sequestered to the Royal Palace.''The chapel and hospital of St. Mary Rounceval''

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of Northumberland Avenue, running down to a wharf by the river. It was an Augustinian house, tied to a mother house at Roncesvalles in the Pyrenees. The house and lands were seized for the king in 1379, under a statute "for the forfeiture of the lands of schismatic aliens". Protracted legal action returned some rights to the prior, but in 1414, Henry V suppressed the 'alien' houses. The priory fell into a long decline owing to lack of money and arguments regarding the collection of tithes with the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. In 1541, religious artefacts were removed to St Margaret's, and the chapel was adapted as a private house; its almshouse were sequestered to the Royal Palace.''The chapel and hospital of St. Mary Rounceval'''' Survey of London'': volume 18: St Martin-in-the-Fields II: The Strand (1937), pp. 1–9. Retrieved 14 February 2009

Battle

In 1554, Charing Cross was the site of the final battle of Wyatt's Rebellion. This was an attempt by Thomas Wyatt and others to overthrow QueenMary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

, soon after her accession to the throne, and replace her with Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

. Wyatt's army had come from Kent, and with London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

barred to them, had crossed the river by what was then the next bridge upstream, at Hampton Court. Their circuitous route brought them down St Martin's Lane

St Martin's Lane is a street in the City of Westminster, which runs from the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, after which it is named, near Trafalgar Square northwards to Long Acre. At its northern end, it becomes Monmouth Street. St Martin ...

to Whitehall.

The palace was defended by 1000 men under Sir John Gage at Charing Cross; they retreated within Whitehall after firing their shot, causing consternation within, thinking the force had changed sides. The rebels – themselves fearful of artillery on the higher ground around St James's – did not press their attack and marched on to Ludgate, where they were met by the Tower Garrison and surrendered.''Charing Cross, the railway stations, and Old Hungerford Market''''Old and New London'': Volume 3 (1878), pp. 123–134. accessed: 13 February 2009

Civil war removal

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the English Civil War, becoming the subject of a popular Royalist ballad:

At

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the English Civil War, becoming the subject of a popular Royalist ballad:

At the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

(1660 or shortly after) eight of the regicides were executed here, including the notable Fifth Monarchist

The Fifth Monarchists, or Fifth Monarchy Men, were a Protestant sect which advocated Millennialist views, active during the 1649 to 1660 Commonwealth. Named after a prophecy in the Book of Daniel that Four Monarchies would precede the Fifth or ...

, Colonel Thomas Harrison. A statue of Charles I was, likewise in Charles II's reign, erected on the site. This had been made in 1633 by Hubert Le Sueur, in the reign of Charles I, but in 1649 Parliament ordered a man to destroy it; however he instead hid it and brought it back to the new King, Charles II (Charles I's son), and his Parliament who had the statue erected here in 1675.

A prominent

A prominent pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks ...

, where malefactors were publicly flogged, stood alongside for centuries. About 200 yards to the east was the Hungerford Market, established at the end of the 16th century; and to the north was the King's Mews, or Royal Mews, the stables for the Palace of Whitehall and thus the King's own presence at the Houses of Parliament (Palace of Westminster). The whole area of the broad pavements of what was a three-way main junction with private (stables) turn-off was a popular place of street entertainment. Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

records in his diaries visiting the taverns and watching the entertainments and executions that were held there. This was combined with the south of the mews when Trafalgar Square was built on the site in 1832, the rest of the stable yard becoming the National Gallery primarily.

A major London coaching inn, the "Golden Cross" – first mentioned in 1643 – faced this junction. From here, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, coaches linked variously terminuses of: Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Bristol, Cambridge, Holyhead

Holyhead (,; cy, Caergybi , "Cybi's fort") is the largest town and a community in the county of Isle of Anglesey, Wales, with a population of 13,659 at the 2011 census. Holyhead is on Holy Island, bounded by the Irish Sea to the north, and is ...

and York. The inn features in '' Sketches by Boz'', '' David Copperfield'' and '' The Pickwick Papers'' by Charles Dickens. In the latter, the dangers to public safety of the quite low archway to access the inn's coaching yard were memorably pointed out by Mr Jingle:

"Heads, heads – take care of your heads", cried the loquacious stranger as they came out under the low archway which in those days formed the entrance to the coachyard. "Terrible place – dangerous work – other day – five children – mother – tall lady, eating sandwiches – forgot the arch – crash – knock – children look round – mother's head off – sandwich in her hand – no mouth to put it in – head of family off."The story echoes an accident of 11 April 1800, when the Chatham and Rochester coach was emerging from the gateway of the Golden Cross, and "a young woman, sitting on the top, threw her head back, to prevent her striking against the beam; but there being so much luggage on the roof of the coach as to hinder her laying herself sufficiently back, it caught her face, and tore the flesh in a dreadful manner." The inn and its yard, pillory, and what remained of the Royal Mews, made way for Trafalgar Square, and a new Golden Cross Hotel was built in the 1830s on the triangular block fronted by

South Africa House

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

. A nod to this is made by some offices on the Strand, in a building named Golden Cross House.

Replacement

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the Strand with the Charing Cross Hotel. In 1865, a replacement cross was commissioned from E. M. Barry by the South Eastern Railway as the centrepiece of the station forecourt. It is not a replica, being of an ornate

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the Strand with the Charing Cross Hotel. In 1865, a replacement cross was commissioned from E. M. Barry by the South Eastern Railway as the centrepiece of the station forecourt. It is not a replica, being of an ornate Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

Gothic design

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries i ...

based on George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

's Oxford Martyrs' Memorial (1838). The Cross rises in three main stages on an octagonal plan, surmounted by a spire and cross. The shields in the panels of the first stage are copied from the Eleanor Crosses

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was introd ...

and bear the arms of England, Castile, Leon and Ponthieu; above the 2nd parapet are eight statues of Queen Eleanor. The Cross was designated a Grade II* monument on 5 February 1970. The month before, the bronze equestrian statue of Charles, on a pedestal of carved Portland stone, was given Grade I listed protection.

Official use as central point

By the late 18th century, the Charing Cross district was increasingly coming to be perceived as the "centre" of the metropolis (supplanting the traditional heartland of theCity

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

to the east). From the early 19th century, legislation applicable only to the London metropolis used Charing Cross as a central point to define its geographical scope. Its later use in legislation waned in favour of providing a schedule of local government areas and became mostly obsolete with the creation of Greater London

Greater may refer to:

*Greatness, the state of being great

*Greater than, in inequality (mathematics), inequality

*Greater (film), ''Greater'' (film), a 2016 American film

*Greater (flamingo), the oldest flamingo on record

*Greater (song), "Greate ...

in 1965.

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose.

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose. John Ogilby

John Ogilby (also ''Ogelby'', ''Oglivie''; November 1600 – 4 September 1676) was a Scottish translator, impresario and cartographer. Best known for publishing the first British road atlas, he was also a successful translator, noted for publishi ...

's ''Britannia'' of 1675, of which editions and derivations continued to be published throughout the 18th century, used the "Standard" (a former conduit head) in Cornhill; while John Cary's ''New Itinerary'' of 1798 used the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

in Lombard Street. The milestones on the main turnpike road

A toll road, also known as a turnpike or tollway, is a public or private road (almost always a controlled-access highway in the present day) for which a fee (or ''toll'') is assessed for passage. It is a form of road pricing typically implemented ...

s were mostly measured from their terminus which was peripheral to the free-passage urban, London roads. Ten of these are notable: Hyde Park Corner, Whitechapel Church, the southern end of London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

, the east end of Westminster Bridge, Shoreditch Church, Tyburn Turnpike (Marble Arch), Holborn Bars, St Giles's Pound, Hicks Hall (as to the Great North Road), and the Stones' End in The Borough. Some roads into Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

and Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

were measured from St Mary-le-Bow

The Church of St Mary-le-Bow is a Church of England parish church in the City of London. Located on Cheapside, one of the city's oldest and most important thoroughfares, the church was founded in 1080 by Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. Rebui ...

church in the City. Some of these structures were later moved or destroyed, but reference to them persisted as if they still remained in place. An exaggerated but well-meaning criticism was that "all the Books of Roads ... published, differ in the Situation of Mile Stones, and instead of being a Guide to the Traveller, serve only to confound him".

William Camden speculated in 1586 that Roman roads in Britain had been measured from London Stone, a claim thus widely repeated, but unsupported by archaeological or other evidence.

Neighbouring locations

Transport

To the east of the Charing Cross road junction is Charing Cross railway station, situated on The Strand. On the other side of the river, connected by the pedestrian Golden Jubilee Bridges, areWaterloo East

Waterloo East railway station, also known as London Waterloo East, is a railway station in central London on the line from through London Bridge towards Kent, in the south-east of England. It is to the east of London Waterloo railway station ...

and Waterloo

Waterloo most commonly refers to:

* Battle of Waterloo, a battle on 18 June 1815 in which Napoleon met his final defeat

* Waterloo, Belgium, where the battle took place.

Waterloo may also refer to:

Other places

Antarctica

*King George Island (S ...

stations.

The nearest London Underground stations are Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

and Embankment.

References

External links

''Charing Cross Bridge'' in London from Claude Monet, in YOUR CITY AT THE THYSSEN, a Thyssen Museum project on Flickr

*'The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross', Survey of London: volume 16: St Martin-in-the-Fields I: Charing Cross (1935), pp. 258–268. URL

The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross , British History Online

Retrieved 6 March 2014. {{Authority control Areas of London Districts of the City of Westminster Kilometre-zero markers Monuments and memorials in London Execution sites in England London crime history