Chandrapore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''A Passage to India'' is a 1924 novel by English author

''A Passage to India'' is a reflection of Forster's visit to India in 1912–13 and his duration as private secretary to

''A Passage to India'' is a reflection of Forster's visit to India in 1912–13 and his duration as private secretary to

''A Passage to India'' emerged at a time where portrayals of India as a savage, disorganized land in need of domination were more popular in mainstream European literature than romanticized depictions. Forster's novel departed from typical narratives about colonizer-colonized relationships and emphasized a more "unknowable" Orient, rather than characterizing it with exoticism, ancient wisdom and mystery. Postcolonial theorists like Maryam Wasif Khan have termed this novel a Modern Orientalist text, meaning that it portrays the Orient in an optimistic, positive light while simultaneously challenging and critiquing European culture and society. However, Benita Parry suggests that it also mystifies India by creating an "obfuscated realm where the secular is scanted, and in which India’s long traditions of mathematics, science and technology, history, linguistics and jurisprudence have no place."

One of the most notable critiques comes from literary professor

''A Passage to India'' emerged at a time where portrayals of India as a savage, disorganized land in need of domination were more popular in mainstream European literature than romanticized depictions. Forster's novel departed from typical narratives about colonizer-colonized relationships and emphasized a more "unknowable" Orient, rather than characterizing it with exoticism, ancient wisdom and mystery. Postcolonial theorists like Maryam Wasif Khan have termed this novel a Modern Orientalist text, meaning that it portrays the Orient in an optimistic, positive light while simultaneously challenging and critiquing European culture and society. However, Benita Parry suggests that it also mystifies India by creating an "obfuscated realm where the secular is scanted, and in which India’s long traditions of mathematics, science and technology, history, linguistics and jurisprudence have no place."

One of the most notable critiques comes from literary professor

E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

set against the backdrop of the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

and the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

in the 1920s. It was selected as one of the 100 great works of 20th century English literature by the ''Modern Library

The Modern Library is an American book publishing imprint and formerly the parent company of Random House. Founded in 1917 by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright as an imprint of their publishing company Boni & Liveright, Modern Library became an ...

'' and won the 1924 James Tait Black Memorial Prize

The James Tait Black Memorial Prizes are literary prizes awarded for literature written in the English language. They, along with the Hawthornden Prize, are Britain's oldest literary awards. Based at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, Uni ...

for fiction. ''Time'' magazine included the novel in its "All Time 100 Novels" list. The novel is based on Forster's experiences in India, deriving the title from Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

's 1870 poem " Passage to India" in ''Leaves of Grass

''Leaves of Grass'' is a poetry collection by American poet Walt Whitman. Though it was first published in 1855, Whitman spent most of his professional life writing and rewriting ''Leaves of Grass'', revising it multiple times until his death. T ...

''.

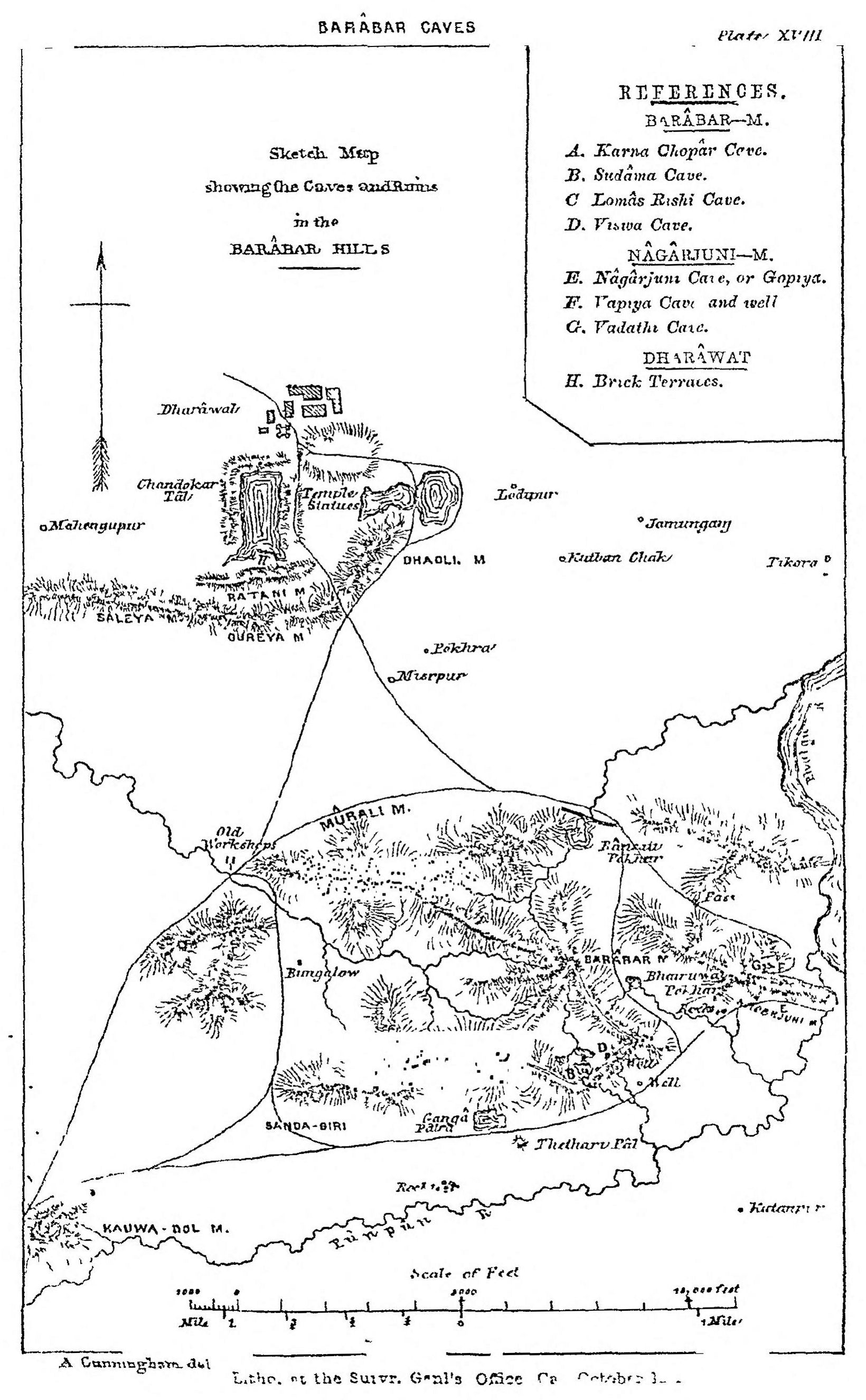

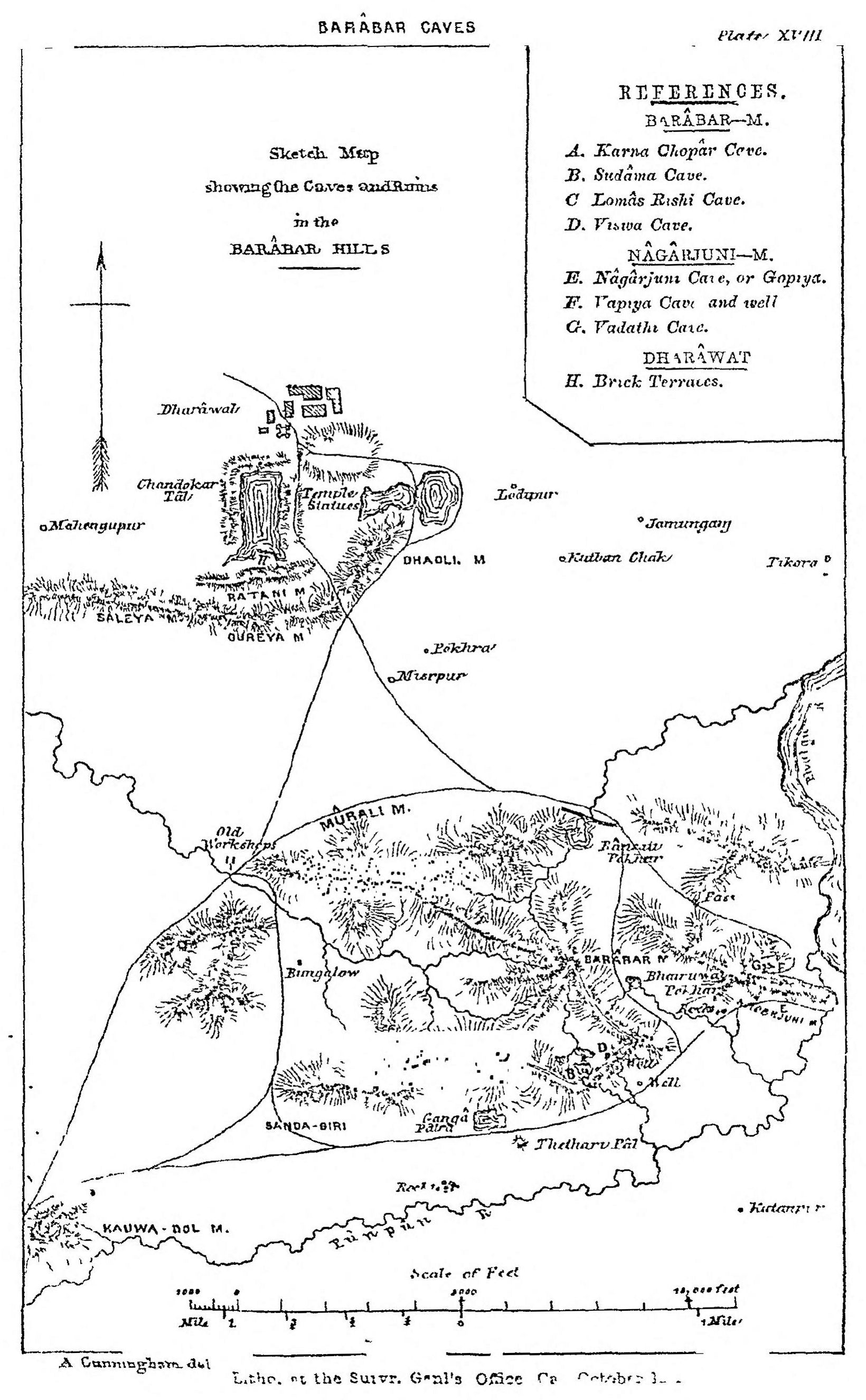

The story revolves around four characters: Dr. Aziz, his British friend Mr. Cyril Fielding, Mrs. Moore, and Miss Adela Quested. During a trip to the fictitious Marabar Caves

The Marabar Caves are fictional caves which appear in E. M. Forster's 1924 novel '' A Passage to India'' and the film of the same name. The caves are based on the real life Barabar Caves, especially the Lomas Rishi Cave, located in the Jehanab ...

(modeled on the Barabar Caves

The Barabar Hill Caves (Hindi बराबर, ''Barābar'') are the oldest surviving rock-cut caves in India, dating from the Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE), some with Ashokan inscriptions, located in the Makhdumpur region of Jehanabad distric ...

of Bihar), Adela thinks she finds herself alone with Dr. Aziz in one of the caves (when in fact he is in an entirely different cave; whether the attacker is real or a reaction to the cave is ambiguous), and subsequently panics and flees; it is assumed that Dr. Aziz has attempted to assault her. Aziz's trial, and its run-up and aftermath, bring to a boil the common racial tensions and prejudices between Indians and the British during the colonial era.

Background

''A Passage to India'' is a reflection of Forster's visit to India in 1912–13 and his duration as private secretary to

''A Passage to India'' is a reflection of Forster's visit to India in 1912–13 and his duration as private secretary to Tukojirao III

Tukojirao III (1 January 1888 – 21 December 1937) was the ruling Maharaja of the Maratha princely state of Dewas from 1900 to 1937. He succeeded to the ''gadi'' of Dewas following the death of his uncle, Raja Krishnajirao II. His tutor and ...

, the Maharajah of Dewas Senior in 1921–22. He dedicated the book to his friend Ross Masood

Syed Sir Ross Masood bin Mahmood Khan (15 February 1889 – 30 July 1937), was the Vice-Chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University starting in 1929.

Early life and career

Ross Masood was the son of Syed Mahmood. His grandfather was Sir Sye ...

.

Plot summary

British schoolmistress, Adela Quested, and her elderly friend, Mrs. Moore, visit the fictional Indian city of Chandrapore. Adela is to decide if she wants to marry Mrs. Moore's son, Ronny Heaslop, the city magistrate. Meanwhile, Dr. Aziz, a young Indian Muslim physician, is called from dining with friends by Major Callendar, Aziz's superior at the hospital, but is delayed. Disconsolate at finding him gone, Aziz walks back and enters his favourite mosque on impulse. Seeing Mrs Moore there, he yells at her not to profane this sacred place, but the two then chat and part as friends. When Mrs. Moore relates her experience later, Ronny becomes indignant at the native's presumption. Because the newcomers had expressed a desire to meet Indians, Mr. Turton, the city tax collector, invites several to his house, but the party turns out awkwardly, due to the Indians' timidity and the Britons' bigotry. Also there is Cyril Fielding, principal of Chandrapore's government-run college for Indians, who invites Adela and Mrs. Moore to a tea party with him and a Hindu-Brahmin professor named Narayan Godbole. At Adela's request, he extends his invitation to Dr. Aziz. At the party, Fielding and Aziz become friends and Aziz promises to take Mrs. Moore and Adela to see the distant Marabar Caves. Ronny arrives and, finding Adela "unaccompanied" with Dr. Aziz and Professor Godbole, rudely breaks up the party. Aziz mistakenly believes that the women are offended that he has not followed through on his promise and arranges an outing to the caves at great expense to himself. Fielding and Godbole are supposed to accompany the expedition, but they miss the train. In the first cave they visit, Mrs. Moore is overcome with claustrophobia and disturbed by the echo. When she declines to continue, Adela and Aziz climb the hill to the upper caves, accompanied by a guide. Asked by Adela whether he has more than one wife, Aziz is disconcerted by her bluntness and ducks into a cave to compose himself. When he comes out, he is told by the guide that Adela has gone into a cave by herself. After quarreling with the guide, Aziz discovers Adela's field glasses broken on the ground and puts them in his pocket. He then looks down the hill and sees Adela speaking to Miss Derek, who has arrived with Fielding in a car. Aziz runs down and greets Fielding, but Miss Derek and Adela drive off, leaving Fielding, Mrs. Moore and Aziz to return to Chandrapore by train. Aziz is arrested on arrival and charged with sexually assaulting Adela. The run-up to his trial increases racial tensions. Adela alleges that Aziz followed her into the cave and that she fended him off by swinging her field glasses at him. The only evidence is the field glasses in the possession of Aziz. When Fielding proclaims his belief in Aziz's innocence, he is ostracised and condemned as a blood-traitor. While awaiting the trial, Mrs Moore becomes concerned at her failing health; taking a ship to England, she dies on the way. Then during the trial, Adela admits that she had been similarly disoriented by the cave's echo. She was no longer sure who or what had attacked her and, despite great demand to persist in her accusation, withdrew the charge. When the case is dismissed, Heaslop breaks off his engagement to Adela and she stays at Fielding's house until a return to England is arranged. Although he is vindicated, Aziz is angry that Fielding befriended Adela after she nearly ruined his life. Believing it to be the gentlemanly thing to do, Fielding convinces Aziz not to seek monetary redress, but the men's friendship suffers and Fielding departs for England. Believing that he is leaving to marry Adela for her money, and bitter at his friend's perceived betrayal, Aziz vows never again to befriend a white person. Two years later, Aziz has moved to the Hindu-ruled state of Mau and is now the Raja's chief physician by the time Fielding returns, married to Stella, Mrs. Moore's daughter from a second marriage. Though the two meet and Aziz still feels drawn to Fielding, he realises that they cannot be truly friends until India becomes independent from British rule.Character list

; Dr. Aziz : A youngMuslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Indian physician who works at the British hospital in Chandrapore.

; Cyril Fielding : The 45-year-old, unmarried British headmaster of the small government-run college for Indians.

; Adela Quested : A young British schoolmistress who is visiting India with the vague intention of marrying Ronny Heaslop.

; Mrs. Moore : The mother of Ronny Heaslop.

; Ronny Heaslop : The British city magistrate of Chandrapore.

; Professor Narayan Godbole : (pronounced )

; Mr. Turton : The British city collector of Chandrapore.

; Mrs. Turton : Mr. Turton's openly racist wife.

; Maj. Callendar : The British head doctor and Aziz's superior at the hospital.

; Mr. McBryde : The British superintendent of police in Chandrapore.

; Miss Derek : An Englishwoman employed by a Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

who frequently borrows their car.

; Nawab Bahadur : The chief Indian citizen in Chandrapore.

; Hamidullah : Aziz's uncle.

; Amritrao : A prominent Indian lawyer called in to defend Aziz.

; Mahmoud Ali : A Muslim Indian barrister who openly hates the British.

; Dr. Panna Lal : A low-born Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

doctor and Aziz's rival at the hospital.

; Ralph Moore : The second son of Mrs. Moore.

; Stella Moore (later Fielding): Mrs. Moore's daughter.

Literary criticism

The nature of critiques of ''A Passage to India'' is largely based upon the era of writing and the nature of the critical work. While many earlier critiques found that Forster's book showed an inappropriate friendship between colonizers and the colonized, new critiques on the work draw attention to the depictions of sexism, racism and imperialism in the novel. Reviews of ''A Passage to India'' when it was first published challenged specific details and attitudes included in the book that Forster drew from his own time in India. Early critics also expressed concern at the interracial camaraderie between Aziz and Fielding in the book. Others saw the book as a vilification ofhumanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

perspectives on the importance of interpersonal relationships, and effects of colonialism on Indian society. More recent critiques by postcolonial theorists and literary critics have reinvestigated the text as a work of Orientalist fiction contributing to a discourse on colonial relationships by a European. Today it is one of the seminal texts in the postcolonial Orientalist discourse, among other books like ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel ...

'' by Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

, and ''Kim

Kim or KIM may refer to:

Names

* Kim (given name)

* Kim (surname)

** Kim (Korean surname)

*** Kim family (disambiguation), several dynasties

**** Kim family (North Korea), the rulers of North Korea since Kim Il-sung in 1948

** Kim, Vietnamese f ...

'' by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

.

''A Passage to India'' emerged at a time where portrayals of India as a savage, disorganized land in need of domination were more popular in mainstream European literature than romanticized depictions. Forster's novel departed from typical narratives about colonizer-colonized relationships and emphasized a more "unknowable" Orient, rather than characterizing it with exoticism, ancient wisdom and mystery. Postcolonial theorists like Maryam Wasif Khan have termed this novel a Modern Orientalist text, meaning that it portrays the Orient in an optimistic, positive light while simultaneously challenging and critiquing European culture and society. However, Benita Parry suggests that it also mystifies India by creating an "obfuscated realm where the secular is scanted, and in which India’s long traditions of mathematics, science and technology, history, linguistics and jurisprudence have no place."

One of the most notable critiques comes from literary professor

''A Passage to India'' emerged at a time where portrayals of India as a savage, disorganized land in need of domination were more popular in mainstream European literature than romanticized depictions. Forster's novel departed from typical narratives about colonizer-colonized relationships and emphasized a more "unknowable" Orient, rather than characterizing it with exoticism, ancient wisdom and mystery. Postcolonial theorists like Maryam Wasif Khan have termed this novel a Modern Orientalist text, meaning that it portrays the Orient in an optimistic, positive light while simultaneously challenging and critiquing European culture and society. However, Benita Parry suggests that it also mystifies India by creating an "obfuscated realm where the secular is scanted, and in which India’s long traditions of mathematics, science and technology, history, linguistics and jurisprudence have no place."

One of the most notable critiques comes from literary professor Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (; , ; 1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American professor of literature at Columbia University, a public intellectual, and a founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies.Robert Young, ''White ...

, who referenced ''A Passage to India'' in both ''Culture and Imperialism

''Culture and Imperialism'' (1993), by Edward Said, is a collection of thematically related essays that trace the connection between imperialism and culture throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. The essays expand the arguments of '' Orie ...

'' and ''Orientalism

In art history, literature and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world. These depictions are usually done by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist p ...

''. In his discussion about allusions to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

in early 20th century novels, Said suggests that though the work subverted typical views on colonialism and colonial rule in India, it also fell short of outright condemning either nationalist movements in India or colonialism itself. Of Forster's attitude toward colonizer-colonized relationships, Said says Forster:. . . found a way to use the mechanism of the novel to elaborate on the already existing structure of attitude and reference without changing it. This structure permitted one to feel affection for and even intimacy with some Indians and India generally, but made one see Indian politics as the charge of the British, and culturally refused a privilege to India nationalism.Stereotyping and Orientalist thought is also explored in postcolonial critiques. Said suggests that Forster deals with the question of British-Indian relationships by separating Muslims and Hindus in the narrative. He says Forster connects Islam to Western values and attitudes while suggesting that Hinduism is chaotic and orderless, and subsequently uses Hindu characters as the background to the main narrative. Said also identifies the failed attempt at friendship between Aziz and Fielding as a reinforcement of the perceived cultural distance between the Orient and the West. The inability of the two men to begin a meaningful friendship is indicative of what Said suggests is the irreconcilable otherness of the Orient, something that has originated from the West and also limits Western readers in how they understand the Orient. Other scholars have examined the book with a critical postcolonial and

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

lens. Maryam Wasif Khan's reading of the book suggests ''A Passage to India'' is also a commentary on gender, and a British woman's place within the empire. Khan argued that the female characters coming to "the Orient" to break free of their social roles in Britain represent the discord between Englishwomen and their social roles at home, and tells the narrative of "pioneering Englishwomen whose emergent feminism found form and voice in the colony".

Sara Suleri

Sara Goodyear ( Suleri; June 12, 1953 – March 20, 2022) was a Pakistan-born American author and professor of English at Yale University, where her fields of study and teaching included Romantic and Victorian poetry and an interest in Edmund ...

has also critiqued the book's orientalist depiction of India and its use of racialized bodies, especially in the case of Aziz, as sexual objects rather than individuals.

Awards

* 1924James Tait Black Memorial Prize

The James Tait Black Memorial Prizes are literary prizes awarded for literature written in the English language. They, along with the Hawthornden Prize, are Britain's oldest literary awards. Based at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, Uni ...

for fiction.

* 1925 Femina Vie Heureuse

Adaptations

* ''A Passage to India'' (play), A play written bySantha Rama Rau

Santha Rama Rau (24 January 1923 – 21 April 2009) was an Indian-born American writer.

Early life and background

While Santha's father was a Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin from Canara whose mother-tongue was Konkani, her mother was a Ka ...

based on the novel that ran on the West End in 1960, and on Broadway in 1962. A 1965 BBC television version of the play was broadcast in their ''Play of the Month

''Play of the Month'' is a BBC television anthology series, which ran from 1965 to 1983 featuring productions of classic and contemporary stage plays (or adaptations) which were usually broadcast on BBC1. Each production featured a different wor ...

'' series.

* The Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray (; 2 May 1921 – 23 April 1992) was an Indian director, screenwriter, documentary filmmaker, author, essayist, lyricist, magazine editor, illustrator, calligrapher, and music composer. One of the greatest auteurs of fil ...

intended to direct a theatrical adaptation of the novel, but the project was never realised.

* The 1984 film version directed by David Lean, and starring Judy Davis

Judith Davis (born 23 April 1955) is an Australian actress in film, television, and on stage. With a career spanning over 40 years, she has been commended for her versatility and regarded as one of the finest actresses of her generation. Frequen ...

, Victor Banerjee

Victor Banerjee is an Indian actor who appears in English, Hindi, Bengali and Assamese language films. He has worked for directors such as Roman Polanski, James Ivory, Sir David Lean, Jerry London, Ronald Neame, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Shya ...

, James Fox

William Fox (born 19 May 1939), known professionally as James Fox, is an English actor. He appeared in several notable films of the 1960s and early 1970s, including '' King Rat'', '' The Servant'', ''Thoroughly Modern Millie'' and ''Performan ...

, Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

and Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including ''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (194 ...

, won two Oscars

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

and numerous other awards.

* Martin Sherman

Martin Gerald Sherman (born December 22, 1938) is an American dramatist and screenwriter best known for his 20 stage plays which have been produced in over 60 countries. He rose to fame in 1979 with the production of his play '' Bent'', which e ...

wrote an additional version for the stage, that premiered at the Shared Experience Shared Experience is a British theatre company.

Its current joint in

''A Passage to India''

at the

Detailed analyses, chapter summaries, a quiz and essay questions

by SparkNotes

reprinted by ''The Guardian'' * , from which the title of Forster's novel was derived {{DEFAULTSORT:Passage To India, A 1924 British novels BBC television dramas British novels adapted into films Modernist novels Novels by E. M. Forster Novels set in India Postcolonial novels 1960 plays Novels set in British India

Its current joint in

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

in 2002. It has toured the UK and played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) is a performing arts venue in Brooklyn, New York City, known as a center for progressive and avant-garde performance. It presented its first performance in 1861 and began operations in its present location in ...

Harvey Theater

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) is a performing arts venue in Brooklyn, New York City, known as a center for progressive and avant-garde performance. It presented its first performance in 1861 and began operations in its present location in ...

in November 2004.

Manuscript

In 1960, the manuscript of ''A Passage to India'' was donated toRupert Hart-Davis

Sir Rupert Charles Hart-Davis (28 August 1907 – 8 December 1999) was an English publisher and editor. He founded the publishing company Rupert Hart-Davis Ltd. As a biographer, he is remembered for his ''Hugh Walpole'' (1952), as an editor, f ...

by Forster and sold to raise money for the London Library

The London Library is an independent lending library in London, established in 1841. It was founded on the initiative of Thomas Carlyle, who was dissatisfied with some of the policies at the British Museum Library. It is located at 14 St James' ...

, fetching the then record sum of £6,500 for a modern English manuscript.Hart-Davis, Rupert: ''Halfway to Heaven'' p55, Sutton Publishing Ltd, Stroud, 1998.

See also

* Stereotypes of South AsiansReferences

* S. M. Chanda: ''A Passage to India: a close look in studies in literature'' (Atlantic Publishers, New Delhi 2003)External links

*''A Passage to India''

at the

British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

*

*

Detailed analyses, chapter summaries, a quiz and essay questions

by SparkNotes

reprinted by ''The Guardian'' * , from which the title of Forster's novel was derived {{DEFAULTSORT:Passage To India, A 1924 British novels BBC television dramas British novels adapted into films Modernist novels Novels by E. M. Forster Novels set in India Postcolonial novels 1960 plays Novels set in British India