Ceilings Of The Natural History Museum, London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A pair of decorated

A pair of decorated

The trustees settled on Montagu House in

The trustees settled on Montagu House in

Waterhouse's design was a Romanesque scheme, loosely based on German religious architecture; Owen was a leading

Waterhouse's design was a Romanesque scheme, loosely based on German religious architecture; Owen was a leading

Waterhouse and Lea's design for the ceiling is based on a theme of growth and power. From the skylights on each side, three rows of panels run the length of the main hall, with the third, uppermost rows on each side meeting at the apex of the roof. The two lower rows are divided into blocks of six panels apiece, each block depicting a different plant species. Plants spread their branches upwards towards the apex, representing the theme of growth. The supporting girders of the ceiling are spaced at every third column of panels, dividing the panels into square blocks of nine; the girders are an integral part of the design, designed to be barely visible from the ground but highly visible from the upper galleries, representing industry working with nature.

The girders themselves are based on 12th-century German architecture. Each comprises a round arch, braced with repeating triangles to create a zig-zag pattern. Within each upward-facing triangle is a highly stylised gilded leaf; the six different leaf designs repeat across the length of the hall. Running perpendicular to the girders—i.e., along the length of the hall—are seven iron support beams. The topmost of these forms the apex of the roof, and the next beam down on each side, separating the topmost from the middle row of panels, is painted with a geometric design of cream and green rectangles. The next beam down on each side, separating the middle from the lowest row of panels, is decorated in the same shades of cream and green, but this time with a design of green triangles pointing upwards. The lowest of the beams, separating the panels from the skylights, is painted deep burgundy and is labelled with the scientific name of the plant depicted in the panels above; the names are flanked with a motif of gilt dots and highly stylised roses. At Owen's request, the plants were labelled with their

Waterhouse and Lea's design for the ceiling is based on a theme of growth and power. From the skylights on each side, three rows of panels run the length of the main hall, with the third, uppermost rows on each side meeting at the apex of the roof. The two lower rows are divided into blocks of six panels apiece, each block depicting a different plant species. Plants spread their branches upwards towards the apex, representing the theme of growth. The supporting girders of the ceiling are spaced at every third column of panels, dividing the panels into square blocks of nine; the girders are an integral part of the design, designed to be barely visible from the ground but highly visible from the upper galleries, representing industry working with nature.

The girders themselves are based on 12th-century German architecture. Each comprises a round arch, braced with repeating triangles to create a zig-zag pattern. Within each upward-facing triangle is a highly stylised gilded leaf; the six different leaf designs repeat across the length of the hall. Running perpendicular to the girders—i.e., along the length of the hall—are seven iron support beams. The topmost of these forms the apex of the roof, and the next beam down on each side, separating the topmost from the middle row of panels, is painted with a geometric design of cream and green rectangles. The next beam down on each side, separating the middle from the lowest row of panels, is decorated in the same shades of cream and green, but this time with a design of green triangles pointing upwards. The lowest of the beams, separating the panels from the skylights, is painted deep burgundy and is labelled with the scientific name of the plant depicted in the panels above; the names are flanked with a motif of gilt dots and highly stylised roses. At Owen's request, the plants were labelled with their

Although the terracotta decorations of the museum do contain some botanical motifs, most of the decor of the building with the exception of the ceiling depicts animals, with extinct species depicted on the east wing and extant species on the west. A statue of

Although the terracotta decorations of the museum do contain some botanical motifs, most of the decor of the building with the exception of the ceiling depicts animals, with extinct species depicted on the east wing and extant species on the west. A statue of

Since the 1975 restoration the ceiling once more began to deteriorate, individual sections of plaster becoming unkeyed (detached from their underlying

Since the 1975 restoration the ceiling once more began to deteriorate, individual sections of plaster becoming unkeyed (detached from their underlying

There are two rows of nine panels apiece on each side of the apex. The central (highest) rows on each side consist of plain green panels, each containing a heraldic rose, thistle or shamrock in representation of England, Scotland and Ireland, the three nations then constituting the United Kingdom. The nine lower panels on each side each illustrate a different plant found in Britain or Ireland.

There are two rows of nine panels apiece on each side of the apex. The central (highest) rows on each side consist of plain green panels, each containing a heraldic rose, thistle or shamrock in representation of England, Scotland and Ireland, the three nations then constituting the United Kingdom. The nine lower panels on each side each illustrate a different plant found in Britain or Ireland.

Interactive and zoomable ultra-high-definition images of the Hintze Hall ceiling

at the

ceilings

A ceiling is an overhead interior surface that covers the upper limits of a room. It is not generally considered a structural element, but a finished surface concealing the underside of the roof structure or the floor of a story above. Ceilings ...

in the main Central Hall (officially Hintze Hall since 2014) and smaller North Hall of the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

, London, were unveiled at the building's opening in 1881. They were designed by the museum's architect Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known f ...

and painted by the artist Charles James Lea

Charles James Lea (1828 or 1829 – 1884) was an English interior artist. He described himself as an ecclesiastical decorator, completing many works mostly in his native Leicestershire before moving to work from Manchester from 1872. Perhaps ...

. The ceiling of the Central Hall consists of 162 panels, 108 of which depict plants considered significant to the history of the museum, to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

or the museum's visitors and the remainder are highly stylised decorative botanical paintings. The ceiling of the smaller North Hall consists of 36 panels, 18 of which depict plants growing in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

. Painted directly onto the plaster of the ceilings, they also make use of gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

for visual effect.

The natural history collections had originally shared a building with their parent institution the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, but with the expansion of the British Empire there was a significant increase in both public and commercial interest in natural history, and in the number of specimens added to the museum's natural history collections. In 1860 it was agreed that a separate museum of natural history would be created in a large building, capable of displaying the largest specimens, such as whales. The superintendent of the natural history departments, Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, envisaged that visitors would enter a large central hall containing what he termed an "index collection" of representative exhibits, from which other galleries would radiate, and a smaller hall to the north would display the natural history of the British Isles. Waterhouse's Romanesque design for the museum included decorative painted ceilings. Acton Smee Ayrton

Acton Smee Ayrton (5 August 1816 – 30 November 1886) was a British barrister and Liberal Party politician. Considered a radical and champion of the working classes, he served as First Commissioner of Works under William Ewart Gladstone between ...

, the First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

, refused to permit the decoration of the ceilings on grounds of cost, but Waterhouse convinced him that provided the painting took place while the scaffolding from the museum's construction was still in place it would incur no extra cost; he further managed to convince Ayrton that the ceiling would be more appealing if elements of the paintings were gilded.

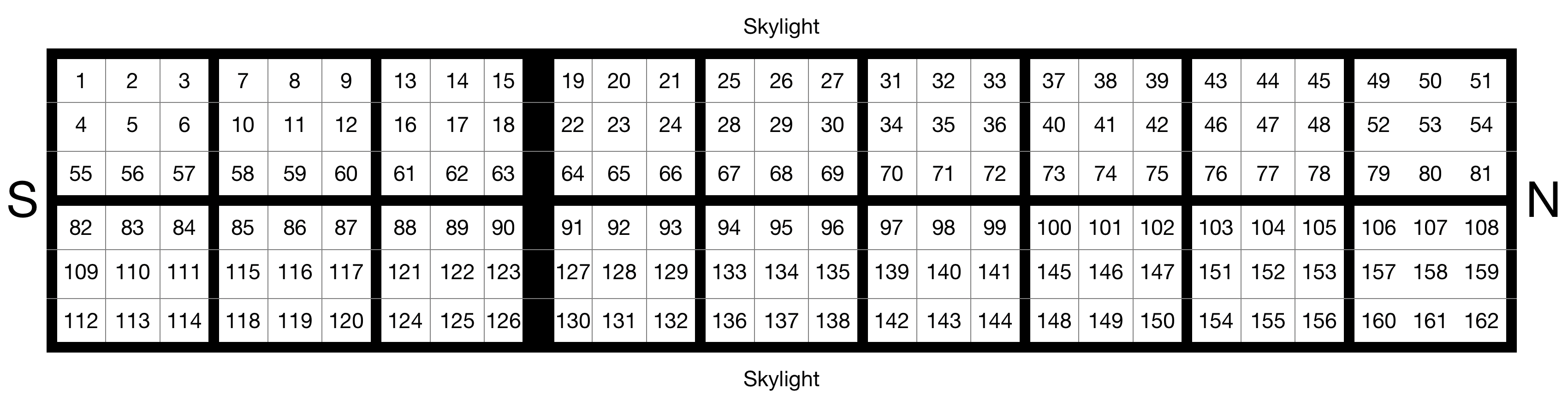

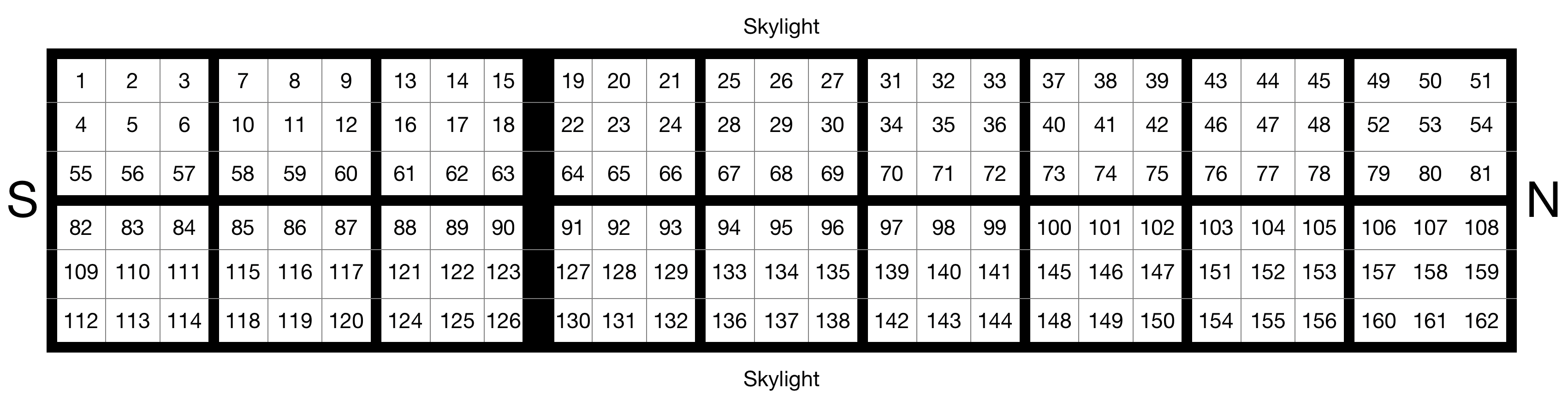

The ceiling of the Central Hall consists of six rows of painted panels, three on each side of the roof's apex. Above the landing at the southern end of the building, the ceiling is divided into nine-panel blocks. The uppermost three panels in each block consist of what Waterhouse termed "archaic" panels, depicting stylised plants on a green background. Each of the lower six panels in each block depicts a plant considered of particular significance to the British Empire, against a pale background. Above the remainder of the Central Hall the archaic panels remain in the same style, but each set of six lower panels depicts a single plant, spreading across the six panels and against the same pale background; these represent plants considered of particular significance either to visitors, or to the history of the museum. The ceiling of the smaller North Hall comprises just four rows of panels. The two uppermost rows are of a simple design of heraldic symbols of the then constituent countries of the United Kingdom; each panel in the lower two rows depicts a different plant found in Britain or Ireland, in keeping with the room's intended purpose as a display of British natural history.

As the ceilings were built cheaply, they are extremely fragile and require regular repair. They underwent significant conservation work in 1924, 1975 and 2016. The restoration in 2016 coincided with the removal of "Dippy

Dippy is a composite ''Diplodocus'' skeleton in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the holotype of the species ''Diplodocus carnegii''. It is considered the most famous single dinosaur skeleton in the world, due to the numerous ...

", a cast of a ''Diplodocus

''Diplodocus'' (, , or ) was a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs, whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a neo-Latin term derived from Greek διπ� ...

'' skeleton which had previously stood in the Central Hall, and the installation of the skeleton of a blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

suspended from the ceiling.

Background

Irish physicianHans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector, with a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Mu ...

was born in 1660, and since childhood had a fascination with natural history. In 1687 Sloane was appointed personal doctor to Christopher Monck

Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle (14 August 1653 – 6 October 1688) was an English soldier and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1667 to 1670 when he inherited the Dukedom and sat in the House of Lords.

Origins

Monc ...

, the newly appointed Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica

This is a list of viceroys in Jamaica from its initial occupation by Spain in 1509, to its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. For a list of viceroys after independence, see Governor-General of Jamaica. For context, see History of Jamai ...

, and lived on that island until Monck died in October 1688. During his free time in Jamaica Sloane indulged his passion for biology and botany, and on his return to London brought with him a collection of plants, animal and mineral specimens and numerous drawings and notes regarding the local wildlife, which eventually became the basis for his major work ''A Voyage to the Islands , Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica'' (1707–1725). He became one of England's leading doctors, credited with the invention of chocolate milk

Chocolate milk is a type of flavoured milk made by mixing cocoa solids with milk (either dairy or plant-based). It is a food pairing in which the milk's mouthfeel masks the dietary fibres of the cocoa solids.

Types

The liquid carbohydrate ...

and with the popularisation of quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg cr ...

as a medicine, and in 1727 King George II appointed him Physician in Ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household, it indicates that a position is a permanent one. In naval matters, vessels "in ordinary" (from the 17th century) are those out of service for repair ...

(doctor to the Royal Household).

Building on the collection he had brought from Jamaica, Sloane continued to collect throughout his life, using his new-found wealth to buy items from other collectors and to buy out the collections of existing museums. During Sloane's life there were few public museums in England, and by 1710 Sloane's collection filled 11 large rooms, which he allowed the public to visit. Following his death on 11 January 1753, Sloane stipulated that his collection—by this time filling two large houses—was to be kept together for the public benefit if at all possible. The collection was initially offered to King George II, who was reluctant to meet the £20,000 (about £ in terms) purchase cost stipulated in Sloane's will. Parliament ultimately agreed to establish a national lottery to fund the purchase of Sloane's collection and the Harleian Library

The Harleian Library, Harley Collection, Harleian Collection and other variants ( la, Bibliotheca Harleiana) is one of the main "closed" collections (namely, historic collections to which new material is no longer added) of the British Library in ...

which was also currently for sale, and to unite them with the Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library is a collection of manuscripts once owned by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton MP (1571–1631), an antiquarian and bibliophile. It later became the basis of what is now the British Library, which still holds the collection. ...

, which had been bequeathed to the nation in 1702, to create a national collection. On 7 June 1753 the British Museum Act 1753

The British Museum Act 1753 ( 26 Geo 2 c 22) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain.

The whole Act was repealed by section 13(5) of, and Schedule 4 to, the British Museum Act 1963. Bylaws, ordinances, statutes or rules in force immedi ...

was passed, authorising the unification of the three collections as the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and establishing the national lottery to fund the purchase of the collections and to provide funds for their maintenance.

Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

as a home for the new British Museum, opening it to the public for the first time on 15 January 1759. With the British Museum now established numerous other collectors began to donate and bequeath items to the museum's collections, which were further swelled by large quantities of exhibits brought to England in 1771 by the first voyage of James Cook

The first voyage of James Cook was a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the south Pacific Ocean aboard HMS ''Endeavour'', from 1768 to 1771. It was the first of three Pacific voyages of which James Cook was the commander. The ...

, by a large collection of Egyptian antiquities (including the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle te ...

) ceded by the French in the Capitulation of Alexandria

The Capitulation of Alexandria in August 1801 brought to an end the French campaign in Egypt and Syria, French expedition to Egypt.

Background

French troops, defeated by British and Ottoman forces, had retreated to Alexandria where they were Si ...

, by the 1816 purchase of the Elgin Marbles

The Elgin Marbles (), also known as the Parthenon Marbles ( el, Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, lit. "sculptures of the Parthenon"), are a collection of Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of the architect and s ...

by the British government who in turn passed them to the museum, and by the 1820 bequest of the vast botanical collections of Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

. Other collectors continued to sell, donate or bequeath their collections to the museum, and by 1807 it was clear that Montagu House was unable to accommodate the museum's holdings. In 1808–09, in an effort to save space, the newly appointed keeper of the natural history department George Shaw George Shaw may refer to:

* George Shaw (biologist) (1751–1813), English botanist and zoologist

* George B. Shaw (1854–1894), U.S. Representative from Wisconsin

* George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Irish playwright

* George C. Shaw (1866–196 ...

felt obliged to destroy large numbers of the museum's specimens in a series of bonfires in the museum's gardens. The 1821 bequest of the library of 60,000 books assembled by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

forced the trustees to address the issue, as the bequest was on condition that the collection be displayed in a single room, and Montagu House had no such room available. In 1823 Robert Smirke was hired to design a replacement building, the first parts of which opened in 1827 and which was completed in the 1840s.

Plans for a Natural History building

upalt=Richard Owen, Richard Owen, 1878 With more space for displays and able to accommodate large numbers of visitors, the new British Museum proved a success with the public, and the natural history department proved particularly popular. Although the museum's management had traditionally been dominated by classicists and antiquarians, in 1856 the natural history department was split into separate departments of botany, zoology, mineralogy and geology, each with their own keeper and with botanist and palaeontologistRichard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

as superintendent of the four departments. By this time the expansion of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

had led to an increased appreciation of the importance of natural history on the part of the authorities, as territorial expansion had given British companies access to unfamiliar species, the commercial possibilities of which needed to be investigated.

By the time of Owen's appointment, the collections of the natural history departments had increased tenfold in size in the preceding 20 years, and the museum was again suffering from a chronic lack of space. There had also long been criticism that because of the varied nature of its displays the museum was confusing and lacked coherence; as early as 1824 Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

, the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, had commented that "what with marbles, statues, butterflies, manuscripts, books and pictures, I think the museum is a farrago that distracts attention". Owen proposed that the museum be split into separate buildings, with one building to house the works of Man (art, antiquities, books and manuscripts) and one to house the works of God (the natural history departments); he argued that the expansion of the British Empire had led to an increased ability to procure specimens, and that increased space to store and display these specimens would both aid scholarship, and enhance Britain's prestige.

In 1858 a group of 120 leading scientists wrote to Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, at the time the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, complaining about the inadequacy of the existing building for displaying and storing the natural history collections. In January 1860, the trustees of the museum approved Owen's proposal. (Only nine of the British Museum's fifty trustees supported Owen's scheme, but 33 trustees failed to turn up to the meeting. As a consequence, Owen's plan passed by nine votes to eight.) Owen envisaged a huge new building of for the natural history collections, capable of exhibiting the largest specimens. Owen felt that exhibiting large animals would attract visitors to the new museum; in particular, he hoped to collect and display whole specimens of large whales while he still had the opportunity, as he felt that the larger species of whale were on the verge of extinction. (It was reported that when the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction

The Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction and the Advancement of Science or the Devonshire Report was a Royal Commission of the United Kingdom that sat from 1870 to 1875.

The Commission was appointed in May 1870 and was chaired by the Duke ...

asked Owen how much space would be needed, he replied "I shall want space for seventy whales, to begin with".) In October 1861 Owen gave William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, the newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, a tour of the cramped natural history departments of the British Museum, to demonstrate how overcrowded and poorly lit the museum's galleries and storerooms were, and to impress on him the need for a much larger building.

alt=Alfred Waterhouse, Alfred Waterhouse, 1878

After much debate over a potential site, in 1864 the site formerly occupied by the 1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, or Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from 1 May to 1 November 1862, beside the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society, South Kensington, London, England, on a site that now houses ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

was chosen. Francis Fowke

Francis Fowke (7 July 1823 – 4 December 1865) was an Irish engineer and architect, and a captain in the Corps of Royal Engineers. Most of his architectural work was executed in the Renaissance style, although he made use of relatively new ...

, who had designed the buildings for the International Exhibition, was commissioned to build Owen's museum. In December 1865 Fowke died, and the Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the England, English Royal Household, royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of W ...

commissioned little-known architect Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known f ...

, who had never previously worked on a building of this scale, to complete Fowke's design. Dissatisfied with Fowke's scheme, in 1868 Waterhouse submitted his own revised design, which was endorsed by the trustees.

Owen, who considered animals more important than plants, was unhappy with the museum containing botanical specimens at all, and during the negotiations that led to the new building supported transferring the botanical collections to the new Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is a ...

to amalgamate the national collections of living and preserved plants. However, he decided that it would diminish the significance of his new museum were it not to cover the whole of nature, and when the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction was convened in 1870 to review the national policy on scientific education Owen successfully lobbied for the museum to retain its botanical collections. In 1873 construction finally began on the new museum building.

Waterhouse's building

Waterhouse's design was a Romanesque scheme, loosely based on German religious architecture; Owen was a leading

Waterhouse's design was a Romanesque scheme, loosely based on German religious architecture; Owen was a leading creationist

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 'th ...

, and felt that the museum served a religious purpose in displaying the works of God. The design was centred around a very large rectangular central hall and a smaller hall to the north. Visitors would enter from the street into the Central Hall, which would hold what Owen termed an "index collection" of typical specimens, intended to serve as an introduction to the museum's collections for those unfamiliar with natural history. Extended galleries were to radiate to the east and west from this central hall to form the south face of the museum, with further galleries to the east, west and north to be added when funds allowed to complete a rectangular shape.

Uniquely for the time, Waterhouse's building was faced inside and out with terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based ceramic glaze, unglazed or glazed ceramic where the pottery firing, fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, a ...

, the first building in England to be so designed; although expensive to build, this was resistant to the acid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists between 6.5 and 8.5, but acid ...

of heavily polluted London, allowed the building to be washed clean, and also allowed it to be decorated with intricate mouldings and sculptures. A smaller North Hall, immediately north of the Central Hall, would be used for exhibits specifically relating to British natural history. On 18 April 1881 the new British Museum (Natural History) opened to the public. As relocating exhibits from Bloomsbury was a difficult and time-consuming process, much of the building remained empty at the time the museum opened.

Central Hall

As well as being large, the Central Hall was to be very high, rising the full height of the building to a plaster-linedmansard roof

A mansard or mansard roof (also called a French roof or curb roof) is a four-sided gambrel-style hip roof characterised by two slopes on each of its sides, with the lower slope, punctured by dormer windows, at a steeper angle than the upper. The ...

, with skylight

A skylight (sometimes called a rooflight) is a light-permitting structure or window, usually made of transparent or translucent glass, that forms all or part of the roof space of a building for daylighting and ventilation purposes.

History

Open ...

s running the length of the hall at the junction between the roof and the wall. A grand staircase at the northern end of the hall, flanked by archways leading to the smaller North Hall, led to balconies running almost the full length of the hall to a staircase which in turn led to a large landing above the main entrance, such that a visitor entering the hall would walk the full length of the floor of the hall to reach the first staircase, and then the full length of the balcony to reach the second. As a consequence, it posed a difficulty to Waterhouse's plans to decorate the building. As the skylights were lower than the ceiling the roof was in relative darkness compared to the rest of the room, and owing to the routes to be taken by visitors, the design needed to be attractive when viewed both from the floor below, and from the raised balconies to the each side. To address this, Waterhouse decided to decorate the ceiling with painted botanical panels.

Acton Smee Ayrton

Acton Smee Ayrton (5 August 1816 – 30 November 1886) was a British barrister and Liberal Party politician. Considered a radical and champion of the working classes, he served as First Commissioner of Works under William Ewart Gladstone between ...

, the First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

, was hostile to the museum project, and sought to cut costs wherever possible; he disliked art, and felt that it was his responsibility to restrain the excesses of artists and architects. Having already insisted that Waterhouse's original design for wooden ceilings and a lead roof be replaced with cheaper plaster and slate, Ayrton vetoed Waterhouse's plan to decorate the ceiling. Waterhouse eventually persuaded Ayrton that provided the ceiling were decorated while the scaffolding from its construction remained in place, a decorated ceiling would be no more expensive than a plain white one. He prepared two sample paintings of the pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

and magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendro ...

for Ayrton, who approved £1435 (about £ in terms) to decorate the ceiling. Having obtained approval for the paintings, Waterhouse managed to convince Ayrton that the paintings' appeal would be enhanced if certain elements were gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

.

Records do not survive of how the plants to be represented were chosen and who created the initial designs. Knapp & Press (2005) believe that it was almost certainly Waterhouse himself, likely working from specimens in the museum's botanical collections, while William T. Stearn

William Thomas Stearn (16 April 1911 – 9 May 2001) was a British botanist. Born in Cambridge in 1911, he was largely self-educated, and developed an early interest in books and natural history. His initial work experience was at a ...

, writing in 1980, believes that the illustrations were chosen by botanist William Carruthers, who at the time was the museum's Keeper of Botany. To create the painted panels from the initial cartoons

A cartoon is a type of visual art that is typically drawn, frequently animated, in an unrealistic or semi-realistic style. The specific meaning has evolved over time, but the modern usage usually refers to either: an image or series of images ...

, Waterhouse commissioned Manchester artist Charles James Lea

Charles James Lea (1828 or 1829 – 1884) was an English interior artist. He described himself as an ecclesiastical decorator, completing many works mostly in his native Leicestershire before moving to work from Manchester from 1872. Perhaps ...

of Best & Lea, with whom he had already worked on Pilmore Hall in Hurworth-on-Tees

Hurworth-on-Tees is a village in the borough of Darlington, within the ceremonial county of County Durham, England. It is situated in the civil parish of Hurworth. The village lies to the south of Darlington on the River Tees, close to its ...

. Waterhouse provided Lea with a selection of botanical drawings, and requested that Lea "select and prepare drawings of fruits and flowers most suitable and gild same in the upper panels of the roof"; it is not recorded who drew the cartoons for the paintings, or how the species were chosen. Best & Lea agreed a fee of £1975 (about £ in terms) for the work. How the panels were painted is not recorded, but it is likely Lea painted directly onto the ceiling from the scaffolding.

Main ceiling

Waterhouse and Lea's design for the ceiling is based on a theme of growth and power. From the skylights on each side, three rows of panels run the length of the main hall, with the third, uppermost rows on each side meeting at the apex of the roof. The two lower rows are divided into blocks of six panels apiece, each block depicting a different plant species. Plants spread their branches upwards towards the apex, representing the theme of growth. The supporting girders of the ceiling are spaced at every third column of panels, dividing the panels into square blocks of nine; the girders are an integral part of the design, designed to be barely visible from the ground but highly visible from the upper galleries, representing industry working with nature.

The girders themselves are based on 12th-century German architecture. Each comprises a round arch, braced with repeating triangles to create a zig-zag pattern. Within each upward-facing triangle is a highly stylised gilded leaf; the six different leaf designs repeat across the length of the hall. Running perpendicular to the girders—i.e., along the length of the hall—are seven iron support beams. The topmost of these forms the apex of the roof, and the next beam down on each side, separating the topmost from the middle row of panels, is painted with a geometric design of cream and green rectangles. The next beam down on each side, separating the middle from the lowest row of panels, is decorated in the same shades of cream and green, but this time with a design of green triangles pointing upwards. The lowest of the beams, separating the panels from the skylights, is painted deep burgundy and is labelled with the scientific name of the plant depicted in the panels above; the names are flanked with a motif of gilt dots and highly stylised roses. At Owen's request, the plants were labelled with their

Waterhouse and Lea's design for the ceiling is based on a theme of growth and power. From the skylights on each side, three rows of panels run the length of the main hall, with the third, uppermost rows on each side meeting at the apex of the roof. The two lower rows are divided into blocks of six panels apiece, each block depicting a different plant species. Plants spread their branches upwards towards the apex, representing the theme of growth. The supporting girders of the ceiling are spaced at every third column of panels, dividing the panels into square blocks of nine; the girders are an integral part of the design, designed to be barely visible from the ground but highly visible from the upper galleries, representing industry working with nature.

The girders themselves are based on 12th-century German architecture. Each comprises a round arch, braced with repeating triangles to create a zig-zag pattern. Within each upward-facing triangle is a highly stylised gilded leaf; the six different leaf designs repeat across the length of the hall. Running perpendicular to the girders—i.e., along the length of the hall—are seven iron support beams. The topmost of these forms the apex of the roof, and the next beam down on each side, separating the topmost from the middle row of panels, is painted with a geometric design of cream and green rectangles. The next beam down on each side, separating the middle from the lowest row of panels, is decorated in the same shades of cream and green, but this time with a design of green triangles pointing upwards. The lowest of the beams, separating the panels from the skylights, is painted deep burgundy and is labelled with the scientific name of the plant depicted in the panels above; the names are flanked with a motif of gilt dots and highly stylised roses. At Owen's request, the plants were labelled with their binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

s rather than their English names, as he felt this would serve an educational purpose to visitors.

Other than on the outermost edges of the panels at the two ends of the hall, each set of nine panels is flanked alongside the girders by an almost abstract design of leaves; these decorations continue along the space between the skylights and the girders to reach the terracotta walls below, providing a visible connection between the walls and the ceiling designs.

Between the main entrance and the landing of the main staircase, the lower two rows of panels all have a pale cream background, intended to draw the viewer's attention to the plant being illustrated; each plant chosen was considered significant either to visitors, or to the museum itself. Each block of three columns depicts a different species, but all have a broadly similar design. The central column in the lowest row depicts the trunk or stalk of the plant in question, while the panels on either side and the three panels of the row above depict the branches of the plant spreading from the lower central panel. The design was intended to draw the viewer's eye upwards, and to give the impression that the plants are growing.

Archaic panels

Above the six-panel sets and adjacent to the apex of the roof lie the top rows of panels. These panels, called the "archaic" panels by Waterhouse, are of a radically different design to those below. Each panel is surrounded by gilded strips and set against a dark green background, rather than the pale cream of the six-panel sets; the archaic panels also continue beyond the six panel sets and over the landing of the main staircase, to run the full length of the Central Hall. The archaic panels depict flattened, stylised plants in pale colours with gilt highlighting, sometimes accompanied by birds, butterflies and insects. Unlike the six-panel sets the archaic panels are not labelled, and while some plants on the archaic panels are recognisable others are stylised beyond recognition. No records survive of how Waterhouse and Lea selected the designs for the archaic panels, or on from which images they were derived. Owing to the flattened nature of the designs, it is possible that they were based onpressed flowers

is the art of using pressed flowers and other botanical materials to create an entire picture from these natural elements.

Such pressed flower art consists of drying flower petals and leaves in a flower press to flatten them, exclude light an ...

in the museum's herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (called ...

, or on illustrations in the British Museum's collection of books on botany. Some of the archaic panels appear to be simplified versions of the illustrations in Nathaniel Wallich

Nathaniel Wolff Wallich FRS FRSE (28 January 1786 – 28 April 1854) was a surgeon and botanist of Danish origin who worked in India, initially in the Danish settlement near Calcutta and later for the Danish East India Company and the British ...

's book ''Plantae Asiaticae Rariores

''Plantae Asiaticae Rariores'' is a horticultural work (alternative title ''Descriptions and figures of a select number of unpublished East Indian plants'') published in 1830–1832 by the Danish botanist Nathaniel Wallich.

''Plantae Asiaticae Ra ...

''.

Balconies

The ceiling of the balconies flanking the Central Hall are also decorated, albeit to a far more simple design. The ceilings are painted with a stencilled motif of square panels, each containing a small illustration of a different plant or animal. All the birds and insects from the archaic panels are included; the panels also feature cacti, cockatoos, crabs, daisies, fish, hawks, lizards, octopuses, pinecones, pomegranates, snails and snakes. The ceilings of the lobbies at the northern end of each balcony—originally the entrances to the museum's refreshment room—are each decorated with a single large panel of stencilled birds, insects, butterflies andpatera

In the material culture of classical antiquity, a ''phiale'' ( ) or ''patera'' () is a shallow ceramic or metal libation bowl. It often has a bulbous indentation ('' omphalos'', "bellybutton") in the center underside to facilitate holding it, ...

e.

South landing

Unlike the cavernous, intentionally cathedral-like feel of the main space of the Central Hall, the ceiling of the landing above the main entrance, connecting the balconies to the upper level, has a different design. Instead of the exposed and decorated iron girders of the main space, the structural girders of this end of the building are faced in the same terracotta style as the building's walls. As the structure of the landing and staircases meant that the ceiling at this end of the room was not clearly visible from the ground floor, there was less of a need to make the designs appear attractive from far below; instead, the design of this stretch of the ceiling was intended to be viewed from a relatively close distance. As with the rest of the Hall, the ceiling is still divided into blocks of nine panels. The archaic panels still run the full length, providing a thematic and visual connection with the rest of the ceiling. The six lower panels of each set do not depict a single plant spreading across each set of panels; instead, each of the 36 panels in the lower two rows depicts a different plant. These each represent a plant considered of particular significance to the British Empire.North Hall

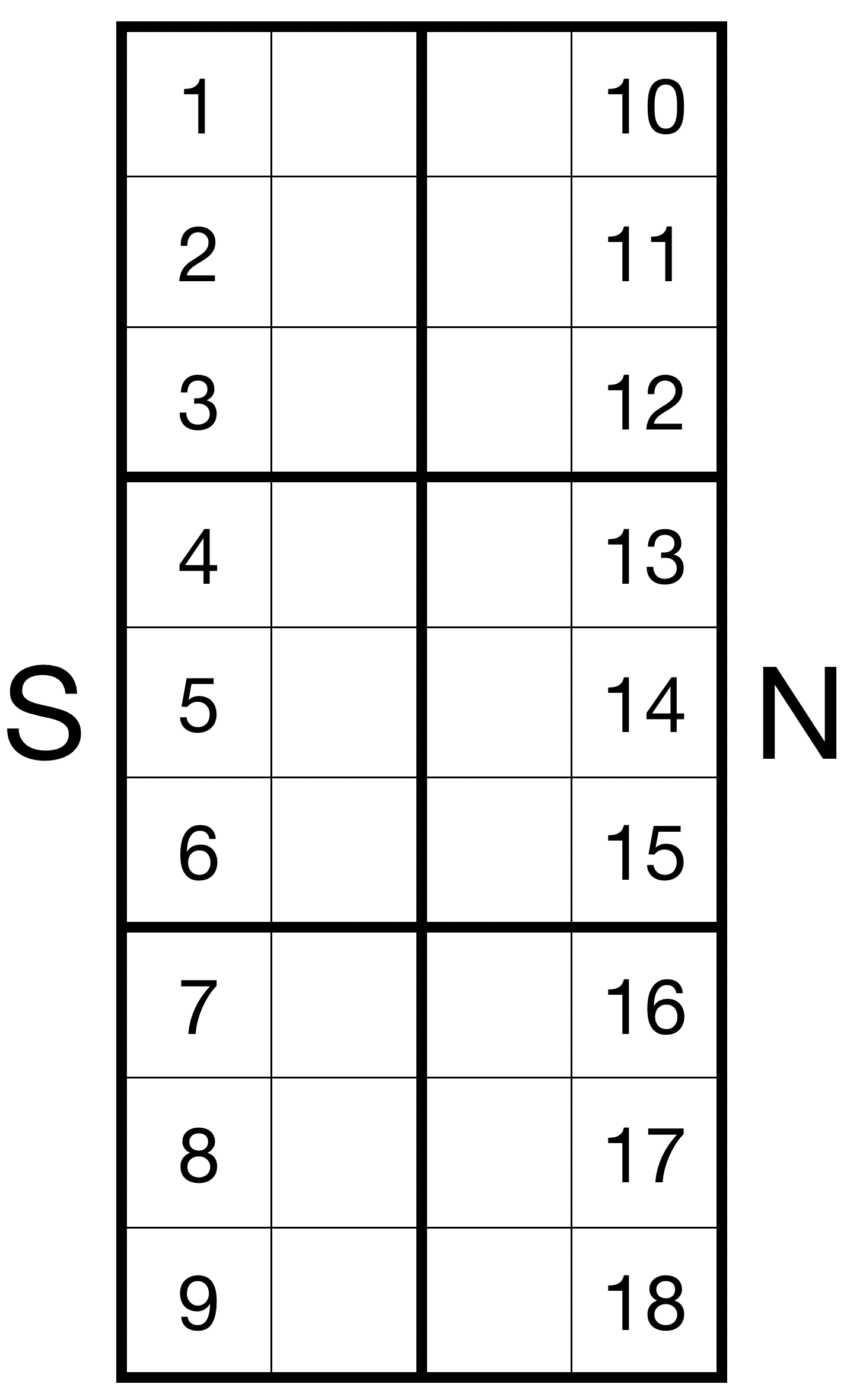

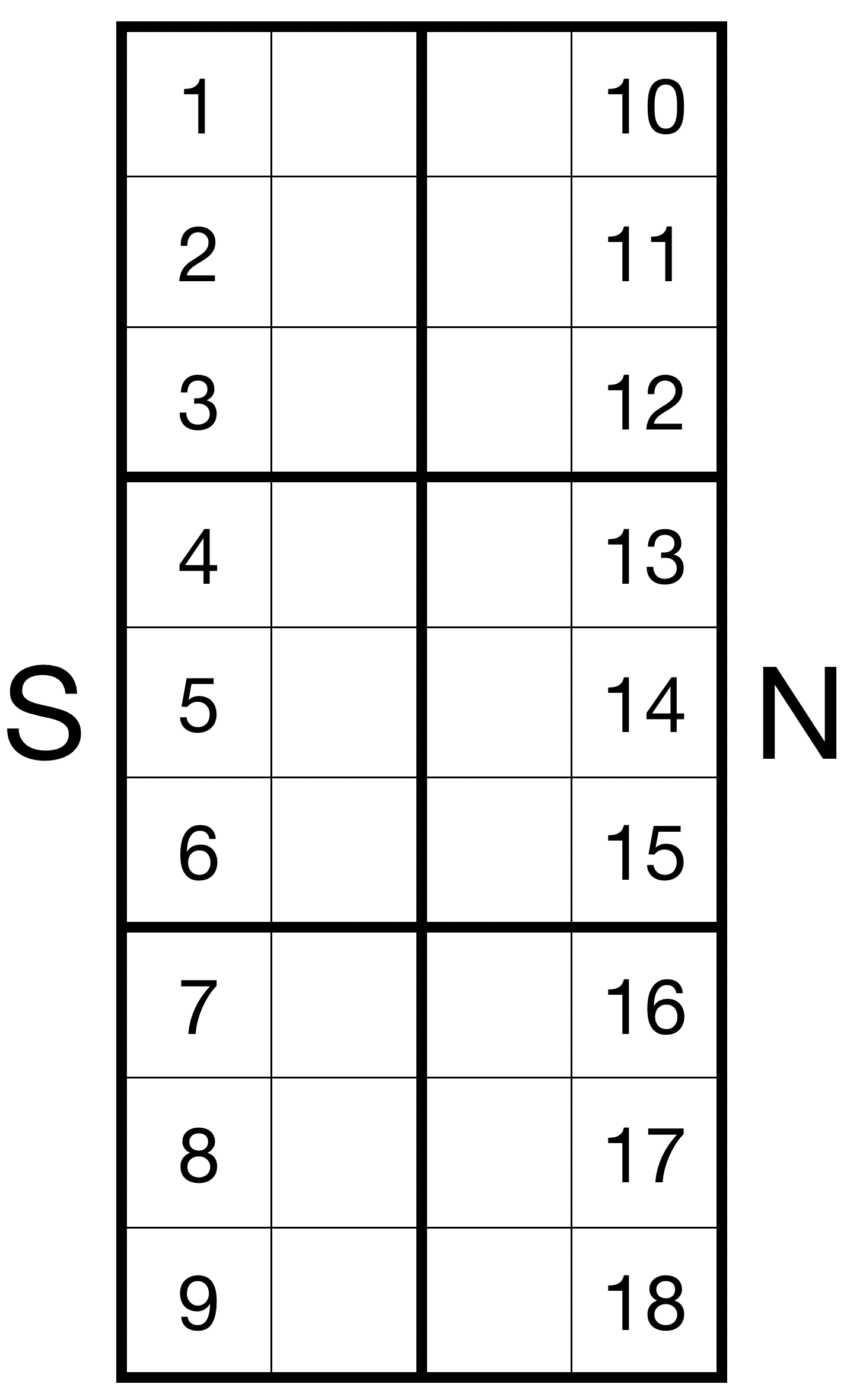

Archways flanking the northern staircase to the balcony level lead to the North Hall, intended by Owen for a display of the natural history of the United Kingdom. Waterhouse designed a ceiling for the North Hall representing this theme. As with the Central Hall, this ceiling comprises rows of panels above a long skylight along each side of the room; there are two rows per side rather than three, and nine panels on each row. Unlike the archaic panels in the top row of the Central Hall, the upper rows on each side consist of plain green panels, each containing a heraldic rose, thistle or shamrock in representation of England, Scotland and Ireland, the three nations then constituting the constituent parts of the United Kingdom. (Wales was not represented, as in this period it was considered a part of England.) In keeping with Owen's intent that the room be used for a display on the topic of the British Isles, the nine lower panels on each side each illustrate a different plant found in Britain or Ireland. The plants depicted were chosen to illustrate the variety of plant habitats in the British Isles. Uniquely in the building, the ceiling panels of the North Hall make use of silver leaf as well as gilt. (During conservation work in 2016 it was found that initially some panels in the Central Hall had also made use of silver leaf, but the silver sections had subsequently been overpainted withochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

.) The style of illustration is similar to that of those over the south landing, but instead of the pale backgrounds of the main ceiling and the panels above the landing, the illustrations in the North Hall are set against a dark green background; Waterhouse's intent was that the darker colour scheme would create an intimate feel by making the ceiling appear lower.

One of the last parts of the initial museum to be completed, the display of British natural history in the North Hall was somewhat arbitrary, and did not reflect Owen's original intentions. Stuffed native animals such as birds and rats were exhibited, alongside prize-winning racehorses, common domesticated animals such as cows and ducks, and an exhibit on commonly grown crops and garden vegetables and on the control of insects. The display was unsuccessful, and was later removed, with the North Hall used as a space for temporary exhibitions before eventually becoming the museum's cafeteria.

After completion

Although the terracotta decorations of the museum do contain some botanical motifs, most of the decor of the building with the exception of the ceiling depicts animals, with extinct species depicted on the east wing and extant species on the west. A statue of

Although the terracotta decorations of the museum do contain some botanical motifs, most of the decor of the building with the exception of the ceiling depicts animals, with extinct species depicted on the east wing and extant species on the west. A statue of Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

originally stood between the two wings over the main entrance, celebrating humanity as the peak of creation, but was dislodged during the Second World War and not replaced. Much was written at the time of the museum's opening about the terracotta decorations of the museum, but very little was written about how the ceiling was received. Knapp & Press (2005) speculate that the apparent lack of public interest in the design of the ceiling could be owing to the prevalence of William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

's ornate floral wallpaper and fabric designs rendering the decorations of the ceiling less unusual to Victorian audiences than might be expected.

Deterioration, restoration and conservation

During the construction of the building Waterhouse had been under intense pressure from the trustees to cut costs, and consequently was forced to abandon his proposed wooden ceiling. Instead, beneath aslate roof

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

, the ceilings were constructed of lath and plaster

Lath and plaster is a building process used to finish mainly interior dividing walls and ceilings. It consists of narrow strips of wood ( laths) which are nailed horizontally across the wall studs or ceiling joists and then coated in plaster. The ...

. The ribs that frame the panels were reinforced with animal hair, but the panels themselves were not reinforced. As a consequence, the ceiling panels are unusually susceptible to vibration and to expansion and contraction caused by temperature variations.

The elaborate nature of the building's design means that its roof slopes at multiple angles, with numerous gutters and gullies, all of which are easily blocked by leaves and wind-blown detritus. As such, during periods of heavy rainfall water often penetrates the slate roof and reaches the fragile plaster ceiling. In 1924 and 1975, the museum has been obliged to repair and restore the ceilings owing to water damage. The height of the Central Hall ceiling made this a complicated and expensive process, requiring floor-to-ceiling scaffolding across the length and width of the Central Hall. The need to avoid damage to the fragile mosaic flooring and the terracotta tiling on the walls caused further difficulty in erecting the scaffolding. The exact nature and the cost of the repairs conducted in 1924 and 1975 is unknown, as is the identity of the restorers, as the relevant records have been lost, although it is known that cracks in the ceiling were filled with plaster and the paintwork and gilding retouched; it is possible that some of the panels were replaced entirely.

During the Second World War, South Kensington was heavily bombed. The north, east, south and west of the building sustained direct bomb hits; the east wing in particular suffered severe damage and its upper floor was left a burned-out shell. The bombs missed the centre of the museum, leaving the fragile ceilings of the Central and North Halls undamaged.

Since the 1975 restoration the ceiling once more began to deteriorate, individual sections of plaster becoming unkeyed (detached from their underlying

Since the 1975 restoration the ceiling once more began to deteriorate, individual sections of plaster becoming unkeyed (detached from their underlying lath

A lath or slat is a thin, narrow strip of straight-grained wood used under roof shingles or tiles, on lath and plaster walls and ceilings to hold plaster, and in lattice and trellis work.

''Lath'' has expanded to mean any type of backing mate ...

s), paintwork peeling from some panels, and the delicate plasterwork cracking. The ends of the Central Hall suffered the worst deterioration, with some cracks above the landing and the northern end of the hall becoming large enough to be visible to the naked eye, while the gilding in the North Hall became gradually tarnished.

In 2001 a systematic programme for the conservation of the ceilings was instituted. A specialised hoist is regularly used to allow a surveyor to take high resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual mak ...

photographs of each panel from a close distance, and the images of each panel used to create a time series

In mathematics, a time series is a series of data points indexed (or listed or graphed) in time order. Most commonly, a time series is a sequence taken at successive equally spaced points in time. Thus it is a sequence of discrete-time data. Exa ...

for each panel. This permits staff to monitor the condition of each panel for deterioration.

In 2014, following a £5,000,000 donation from businessman Michael Hintze

Michael Hintze, Baron Hintze, (born 27 July 1953) is an Australian-British businessman and philanthropist, based in the United Kingdom.

According to the ''Sunday Times'' 2019 Rich List, Hintze's net worth is 1.5 billion, an increase of 1 ...

, Central Hall was formally renamed Hintze Hall. In 2016, in conjunction with works to replace the "Dippy

Dippy is a composite ''Diplodocus'' skeleton in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the holotype of the species ''Diplodocus carnegii''. It is considered the most famous single dinosaur skeleton in the world, due to the numerous ...

" cast of a ''Diplodocus

''Diplodocus'' (, , or ) was a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs, whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a neo-Latin term derived from Greek διπ� ...

'' skeleton which had previously been the Central Hall's centrepiece with the skeleton of a blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

suspended from the ceiling, further conservation work took place. The cracks in the plasterwork were filled, and flaked or peeling paintwork was repaired with Japanese tissue

Japanese tissue is a thin, strong paper made from vegetable fibers. Japanese tissue may be made from one of three plants, the ''kōzo'' plant (''Broussonetia papyrifera'', paper mulberry tree), the mitsumata (''Edgeworthia chrysantha'') shrub ...

.

Layout of the ceiling panels

Central Hall panels

upalt=Tobacco plant, '' Nicotiana tabacum'' as pictured on the ceiling The panels are arranged in blocks of nine. The two central, uppermost rows (55–108) constitute the archaic panels. Of the outer two rows, in the six blocks at the southern end of the hall above the landing and the main entrance (1–18 and 109–126) each panel depicts a different plant considered of particular significance to the British Empire, while the twelve six-panel blocks above the main hall (19–54 and 127–162) each depict a single plant considered of particular importance to visitors or to the history of the museum, spreading across six panels.

North Hall panels

There are two rows of nine panels apiece on each side of the apex. The central (highest) rows on each side consist of plain green panels, each containing a heraldic rose, thistle or shamrock in representation of England, Scotland and Ireland, the three nations then constituting the United Kingdom. The nine lower panels on each side each illustrate a different plant found in Britain or Ireland.

There are two rows of nine panels apiece on each side of the apex. The central (highest) rows on each side consist of plain green panels, each containing a heraldic rose, thistle or shamrock in representation of England, Scotland and Ireland, the three nations then constituting the United Kingdom. The nine lower panels on each side each illustrate a different plant found in Britain or Ireland.

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

Interactive and zoomable ultra-high-definition images of the Hintze Hall ceiling

at the

Google Cultural Institute

Google Arts & Culture (formerly Google Art Project) is an online platform of high-resolution images and videos of artworks and cultural artifacts from partner cultural organizations throughout the world.

It utilizes high-resolution image technol ...

{{featured article

Natural History Museum, London

Alfred Waterhouse buildings

Painted ceilings