Cave of Dogs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cave of Dogs (Italian: ''Grotta del Cane'') is a cave near

The Cave of Dogs (Italian: ''Grotta del Cane'') is a cave near

/ref> and its reputation gave rise to a

Video of a scientific demonstration of the principle behind Cave of Dogs

Report from a scientific expedition to the cave on April 28, 2013

(in Italian) Caves of Italy Carbon dioxide Campanian volcanic arc Cruelty to animals Science demonstrations Toxicology Tourist attractions in Campania Volcanism of Italy Geotourism Phlegraean Fields

The Cave of Dogs (Italian: ''Grotta del Cane'') is a cave near

The Cave of Dogs (Italian: ''Grotta del Cane'') is a cave near Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Volcanic gases seeping into the cave give the air inside a high concentration of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

. Dogs held inside would faint; at one time this was a tourist attraction.

Description

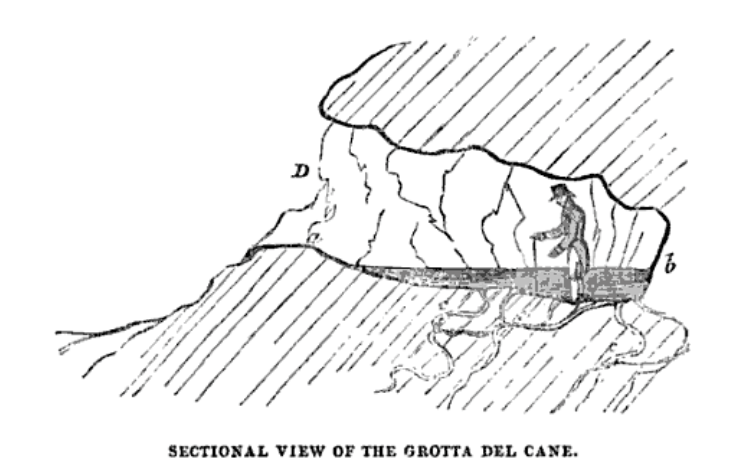

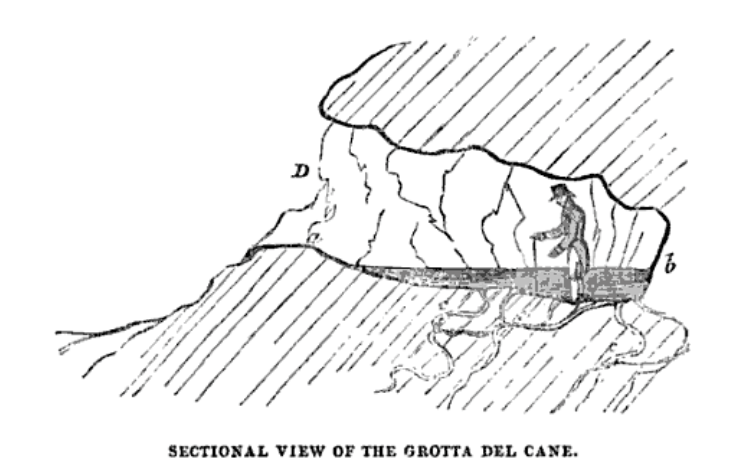

The Cave of Dogs (Italian: ''Grotta del Cane'', literally "Cave of the Dog")) is acave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

about ten metres deep on the eastern side of the Phlegraean Fields

The Phlegraean Fields ( it, Campi Flegrei ; nap, Campe Flegree, from Ancient Greek 'to burn') is a large region of supervolcanic calderas situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It was declared a regional park in 2003. The area of the calde ...

near Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, Δικα ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. Inside the cave is a fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

that releases carbon dioxide of volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

origin.

The cave is thought to have been constructed in classical antiquity, possibly as a sudatorium In architecture, a sudatorium is a vaulted sweating-room ('' sudor'', "sweat") or steam bath (Latin: ''sudationes'', steam) of the Roman baths or thermae. The Roman architectural writer Vitruvius (v. 2) refers to it as ''concamerata sudatio''. It is ...

; if so, the CO emissions must have been much lower at the time. It may have been known to Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, who, in his '' Natural History'' (written 77-79 AD), mentions a location near Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, Δικα ...

where animals die from poisonous fumes. However, the first unambiguous reports about the cave only appear in the 16th century.

It was a tourist attraction

A tourist attraction is a place of interest that tourists visit, typically for its inherent or an exhibited natural or cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, offering leisure and amusement.

Types

Places of natural ...

for travelers on the Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

. The CO gas, being denser than air, tended to accumulate in the deeper parts of the cave. As a result, small animals such as dogs held inside the cave suffered carbon dioxide poisoning, while a standing human was not affected. Local guides, for a fee, would suspend small animals (usually dogs) inside it until they became unconscious. The dogs could be revived by submerging them in the cold waters of the nearby Lake Agnano, although in at least one case this led to the dog drowning instead. Tourists who came to see this attraction included Sir Thomas Browne,

Richard Mead

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

, Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

, John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or ...

, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, Alexandre Dumas père

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer. ...

, and Mark Twain.

Some tourists including Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

(1804), Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel '' Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an early example of science fiction. She also ...

(1818) and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

(1833), objecting to the cruelty, refused to pay for the experiment to be performed on the dog. A Scottish scientist who examined the cave for several days (1877) reported:

The lake became polluted, was thought to be malarious, and was drained in 1870. At some point the spectacle fell into disuse, although Baedeker

Verlag Karl Baedeker, founded by Karl Baedeker on July 1, 1827, is a German publisher and pioneer in the business of worldwide travel guides. The guides, often referred to simply as " Baedekers" (a term sometimes used to refer to similar works fro ...

's guides in the 1880s were still advertising that to see the dog experiment would cost tourists 1 ''lire'' (≈ 20 U.S. cents).. According to one source, it was banned before World War II for cruelty to animals. The cave entrance was blocked to prevent access by children.

In 2001 the cave was investigated by Italian speleologists

Speleology is the scientific study of caves and other karst features, as well as their make-up, structure, physical properties, history, life forms, and the processes by which they form (speleogenesis) and change over time (speleomorphology). ...

. Nine metres from its entrance the temperature was and the CO concentration was 80%, with negligible oxygen.

In popular science

The cave was often described in nineteenth century science textbooks to illustrate thedensity

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

and toxicity of carbon dioxide,The above image is from L'air et le monde aèrien, an 1865 textbook by Arthur Mangin, p.16/ref> and its reputation gave rise to a

scientific demonstration

A scientific demonstration is a procedure carried out for the purposes of demonstrating scientific principles, rather than for hypothesis testing or knowledge gathering (although they may originally have been carried out for these purposes).

Most ...

of the same name, in which stepped candles are successively extinguished by tipping carbon dioxide into a transparent container.

References

{{Coord, 40.833333, N, 14.166667, E, display=titleExternal links

Video of a scientific demonstration of the principle behind Cave of Dogs

Report from a scientific expedition to the cave on April 28, 2013

(in Italian) Caves of Italy Carbon dioxide Campanian volcanic arc Cruelty to animals Science demonstrations Toxicology Tourist attractions in Campania Volcanism of Italy Geotourism Phlegraean Fields