Castellio on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

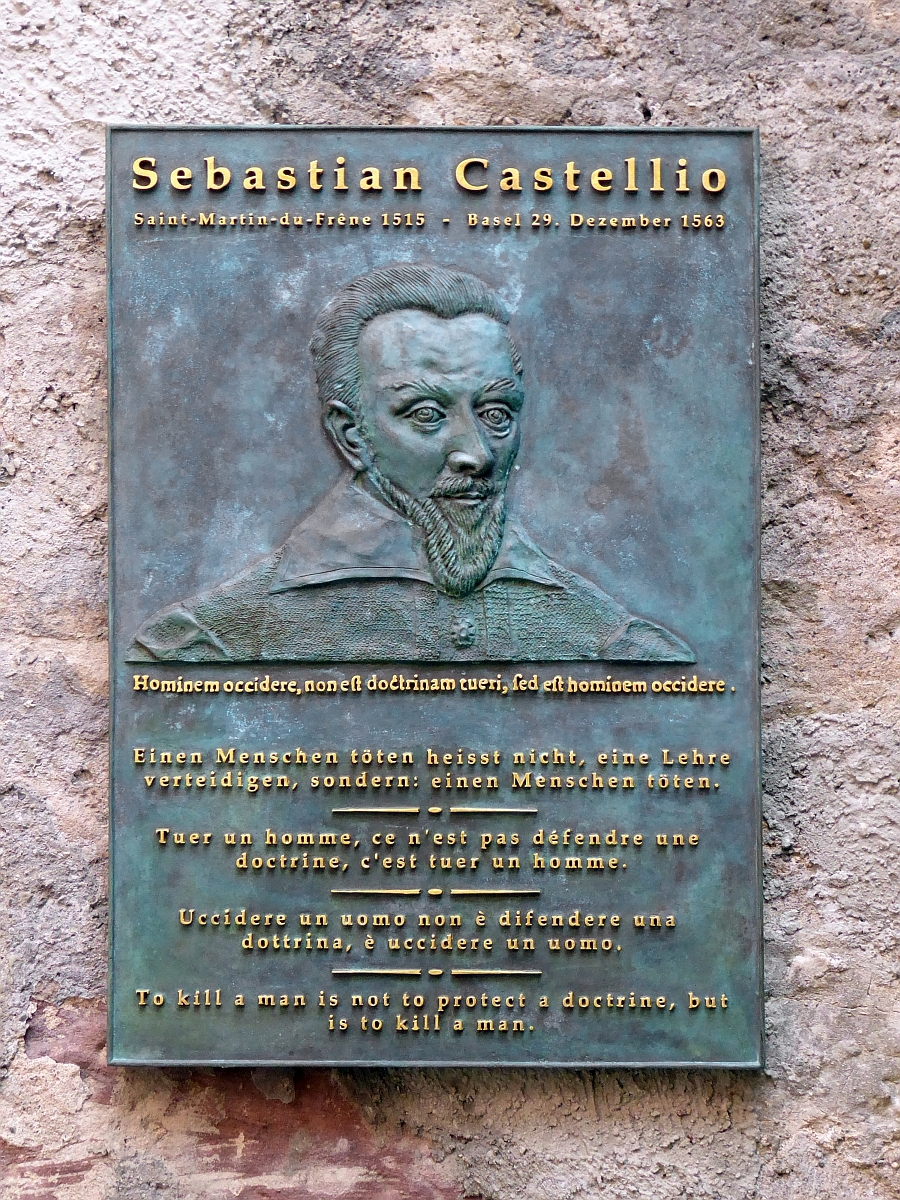

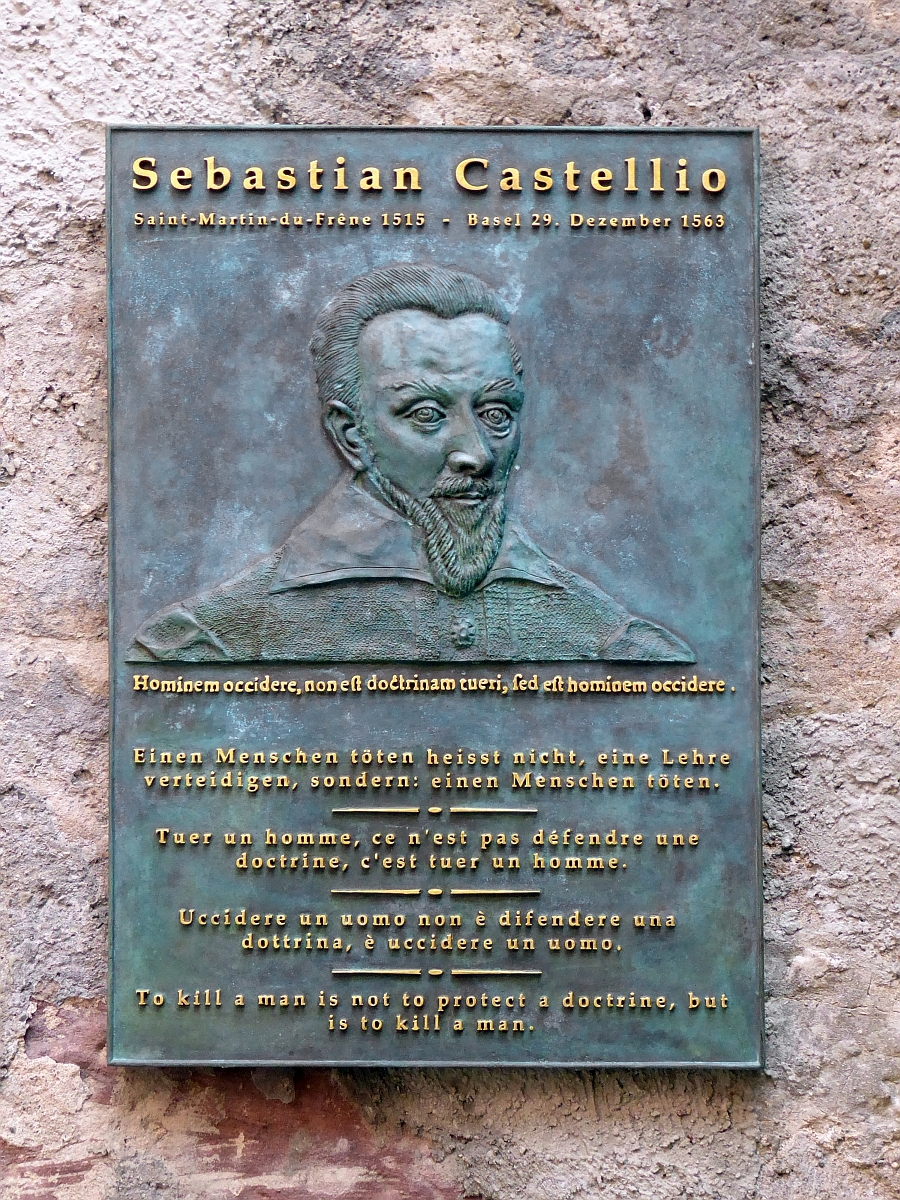

Sebastian Castellio (also Sébastien Châteillon, Châtaillon, Castellión, and Castello; 1515 – 29 December 1563) was a

Sebastian Castellio (also Sébastien Châteillon, Châtaillon, Castellión, and Castello; 1515 – 29 December 1563) was a

Sebastian Castellio

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050306160331/http://www.socinian.org/castellio.html Sebastian Castellio and the Struggle for Freedom of Consciencebr>Sebastian Castellio's Erasmian Liberalism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Castellio, Sebastian 1515 births 1563 deaths People from Ain French Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century French theologians Calvinist pacifists Christianity and politics Cultural critics Moral philosophers 16th-century people from Savoy Philosophers of culture Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of religion Political philosophers Protestant Reformers Religion and politics Secularism Separation of church and state French social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Translators of the Bible into French Translators of the Bible into Latin 16th-century French translators

Sebastian Castellio (also Sébastien Châteillon, Châtaillon, Castellión, and Castello; 1515 – 29 December 1563) was a

Sebastian Castellio (also Sébastien Châteillon, Châtaillon, Castellión, and Castello; 1515 – 29 December 1563) was a French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

preacher

A preacher is a person who delivers sermons or homilies on religious topics to an assembly of people. Less common are preachers who preach on the street, or those whose message is not necessarily religious, but who preach components such as a ...

and theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

; and one of the first Reformed Christian

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

proponents of religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

, freedom of conscience

Conscience is a cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's moral philosophy or value system. Conscience stands in contrast to elicited emotion or thought due to associations based on immediate sens ...

and thought

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, a ...

.

Introduction

Castellio was born in 1515 atSaint-Martin-du-Frêne

Saint-Martin-du-Frêne () is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Ain department

The following is a list of the 393 communes of the Ain department of France.

The communes cooperate in ...

in the village of Bresse of Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

, the country bordering Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, France, and Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

. Under the Savoyard rule his family called itself Chateillon, Chatillon, or Chataillon. Having been educated at the age of twenty at the University of Lyon

The University of Lyon (french: Université de Lyon), located in Lyon and Saint-Étienne, France, is a center for higher education and research comprising 11 members and 24 associated institutions. The three main universities in this center are: ...

, Castellio was fluent in both French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, and became an expert in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

as well. Subsequently, he learned German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

as he started to write theological works in the various languages of Europe

Most languages of Europe belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. Within Indo-European, the three largest phyla are Rom ...

.

His education, zeal and theological knowledge were so outstanding that he was considered to be one of the most learned men of his time - equal, if not superior, to John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

. Regarding Castellio, according to ''The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin'' of Stefan Zweig

Stefan Zweig (; ; 28 November 1881 – 22 February 1942) was an Austrian novelist, playwright, journalist, and biographer. At the height of his literary career, in the 1920s and 1930s, he was one of the most widely translated and popular write ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

wrote: "We can measure the virulence of this tyranny by the persecution to which Castellio was exposed at Calvin's instance—although Castellio was a far greater scholar

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researche ...

than Calvin, whose jealousy drove him out of Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

."

Castellio later wrote that he was deeply affected and moved when he saw the burning of heretics in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

by the French Inquisition, and at the age of twenty-four he decided to subscribe to the teachings of the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. In the spring of 1540, after witnessing the killings of the early Protestant martyrs, he left Lyon and became a missionary for Protestantism.

Early career

After leaving Lyon, Castellio made his way toStrasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

where he met John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

. Having made a very strong impression on Calvin, Castellio enjoyed Calvin's company so much that he remained there for a whole week in the student hostel established by Calvin and his wife. Calvin, upon returning to Geneva, asked Castellio to join him in 1542 as Rector of the Collège de Genève

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

. Castellio was also commissioned to preach in Vandoeuvres, a suburb of Geneva.

Because of his unique relationship with Calvin, Castellio enjoyed great respect in the world of Protestant Christian theology. In 1542 he published his first book of ''Sacred Dialogues'' in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and French.

In 1543, after the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

struck Geneva, Sebastian Castellio was one of the only divines in Geneva to visit the sick and console the dying. Though Calvin himself did visit the sick, others among the Genevan ministers did not.

For his outstanding work, the Geneva City Council recommended Castellio's permanent appointment as preacher in Vandoeuvres; however in 1544 a campaign against him was initiated by Calvin. At the time, Castellio decided to translate the Bible into his native French, and was very excited to ask for an endorsement from his friend Calvin, but Calvin's endorsement was already given to his cousin Pierre Olivetan

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

's French translation of the Bible, so Castellio was rebuked and turned down. Calvin wrote to a friend regarding the matter: "Just listen to Sebastian's preposterous scheme, which makes me smile, and at the same time angers me. Three days ago he called on me, to ask permission for the publication of his translation of the New Testament."

Castellio and Calvin's disagreements grew even wider when during a public meeting Castellio rose to his feet and claimed that clergy should stop persecuting those who disagree with them on matters of Biblical interpretation

Biblical hermeneutics is the study of the principles of interpretation concerning the books of the Bible. It is part of the broader field of hermeneutics, which involves the study of principles of interpretation, both theory and methodology, for ...

, and should be held to the same standards that all other believers were held to. Soon after, Calvin charged Castellio with the offense of "undermining the prestige of the clergy." Castellio was forced to resign from his position of Rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

and asked to be dismissed from being a preacher in Vandoeuvres. Anticipating future attacks from Calvin, Castellio asked for a signed letter that outlined in detail the reasons for his departure: "That no one may form a false idea of the reasons for the departure of Sebastian Castellio, we all declare that he has voluntarily resigned his position as rector at the College, and up till now performed his duties in such a way that we regarded him worthy to become one of our preachers. If, in the end, the affair was not thus arranged, this is not because any fault has been found in Castellio's conduct, but merely for the reasons previously indicated."

Years of poverty

The man who once was the Rector in Geneva was nowhomeless

Homelessness or houselessness – also known as a state of being unhoused or unsheltered – is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and adequate housing. People can be categorized as homeless if they are:

* living on the streets, also kn ...

and in deep poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse social, economic, and political causes and effects. When evaluating poverty in ...

. The next few years were desperate times for him. Though one of the most learned men of his time, his life came down to begging

Begging (also panhandling) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar or panhandler. Beggars may operate in public place ...

for food from door to door. Living in abject poverty with his eight dependents, Castellio was forced to depend on strangers to stay alive. His plight brought sympathy and admiration from his contemporaries. Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Sieur de Montaigne ( ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), also known as the Lord of Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a liter ...

wrote "it was deplorable that a man who had done such good service as Castellio should have fallen upon evil days" and added that "many persons would unquestionably have been glad to help Castellio had they known soon enough that he was in want."

History indicates that many perhaps were afraid to help Castellio for fear of reprisals from Geneva. Castellio's existence ranged from begging and digging ditches for food to proof-reading

Proofreading is the reading of a galley proof or an electronic copy of a publication to find and correct reproduction errors of text or art. Proofreading is the final step in the editorial cycle before publication.

Professional

Traditional ...

for the Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

printshop of Johannes Oporinus

Johannes Oporinus (also Johannes Oporin; Latinised from the original German name: ''Johannes Herbster'' or ''Hans Herbst'') (25 January 1507 – 7 July 1568) was a humanist printer in Basel.

Life

Johannes Oporinus, the son of the painter Hans ...

. He also worked as a private tutor

TUTOR, also known as PLATO Author Language, is a programming language developed for use on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in roughly 1965. TUTOR was initially designed by Paul Tenczar for use in co ...

while translating thousands of pages from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

into French and German. He was also the designated successor to Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

in continuing his work of the reconciliation of Christianity in the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

, and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

branches, and prophetically predicted the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estim ...

, and potentially the destruction of Christianity in Europe

Christianity is the largest religion in Europe. Christianity has been practiced in Europe since the first century, and a number of the Pauline Epistles were addressed to Christians living in Greece, as well as other parts of the Roman Empire.

...

, if Christians could not learn to tolerate and reach each other by love

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, the deepest Interpersonal relationship, interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure. An example of this range of ...

and reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

rather than by force of arms

''Force of Arms'' (reissued under the title ''A Girl for Joe'') is a 1951 romantic war drama film set in the Italian theater of World War II. It reteamed William Holden and Nancy Olson in the third of their four movies together (''Sunset Boul ...

, and in short become real followers of Christ, rather than of bitter, partisan, and sectarian ideologies. His writings were widely circulated in manuscript form for a time, but were later forgotten. John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

desired their publication, but at that time it was a capital crime

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

to even own copies of manuscripts by Castellio or on the Servetus controversy, so Locke's friends convinced him to publish the same ideas under his own name. These writings were remembered by foundational theologians and historians such as Gottfried Arnold

Gottfried Arnold (5 September 1666 – 30 May 1714) was a German Lutheran theologian and historian.

Biography

Arnold was born at Annaberg in Saxony, Germany, where his father was schoolmaster. In 1682, he went to the Gymnasium at Gera and ...

, Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. A Huguenot, Bayle fled to the Dutch Republic in 1681 because of religious persecution in France. He is best known for his '' Historica ...

, Johann Lorenz von Mosheim

Johann Lorenz von Mosheim or Johann Lorenz Mosheim (9 October 1693 – 9 September 1755) was a German Lutheran church historian.

Biography

He was born at Lübeck on 9 October 1693 or 1694. After studying at the '' gymnasium'' of Lübeck, he ent ...

, Johann Jakob Wettstein

Johann Jakob Wettstein (also Wetstein; 5 March 1693 – 23 March 1754) was a Swiss theologian, best known as a New Testament critic.

Biography

Youth and study

Johann Jakob Wettstein was born in Basel. Among his tutors in theology was Samuel We ...

, and Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

.

In 1551, was published; in 1555 was published.

Conflict with Calvin

Castellio's fortunes gradually improved, and in August 1553 he was made a Master of Arts of the University of Basel and appointed to a prestigious teaching position. However, in October 1553, the physician and theologianMichael Servetus

Michael Servetus (; es, Miguel Serveto as real name; french: Michel Servet; also known as ''Miguel Servet'', ''Miguel de Villanueva'', ''Revés'', or ''Michel de Villeneuve''; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish th ...

was executed in Geneva for blasphemy and heresy – in particular, his repudiation of the doctrine of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

. Many prominent Protestant leaders of the day approved of the execution, and Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

wrote to Calvin: "To you also the Church owes gratitude at the present moment, and will owe it to the latest posterity....I affirm also that your magistrates did right in punishing, after a regular trial, this blasphemous man." However, many other contemporary scholars, such as David Joris

David Joris (c. 1501 – 25 August 1556, sometimes Jan Jorisz or Joriszoon; formerly anglicised David Gorge) was an important Anabaptist leader in the Netherlands before 1540.

Life

Joris was probably born in Flanders, the son of Marietje Ja ...

and Bernardino Ochino

Bernardino Ochino (1487–1564) was an Italian, who was raised a Roman Catholic and later turned to Protestantism and became a Protestant reformer.

Biography

Bernardino Ochino was born in Siena, the son of the barber Domenico Ochino, and at the ...

(also known as the remonstrators) were outraged both publicly and privately over the execution of Servetus. The synods of Zurich and Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; gsw, Schafuuse; french: Schaffhouse; it, Sciaffusa; rm, Schaffusa; en, Shaffhouse) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the ...

were far from enthusiastic, and Castellio took an especially hard line regarding the whole affair. He became enraged over what he saw as a blatant murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

committed by Calvin, and spoke of his " hands dripping with the blood of Servetus."

As a defense of his actions, in February 1554 Calvin published a treatise titled ''Defense of the orthodox faith in the sacred Trinity'' (''Defensio orthodoxae fidei de sacra Trinitate'') in which he presented arguments in favor of the execution of Servetus for diverging from orthodox Christian doctrine.

Three months later, Castellio wrote (as Basil Montfort) a large part of the pamphlet ''Should Heretics be Persecuted?'' (''De haereticis, an sint persequendi'') with the place of publication being given on the first page as Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebur ...

rather than Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

. The book was financed by the wealthy Italian Bernardino Bonifazio, was published under the pseudonym ''Martinus Bellius'', and was printed by Johannes Oporinus, a known Basel book printer. It is believed that the pamphlet was co-authored by Laelius Socinus

Lelio Francesco Maria Sozzini, or simply Lelio Sozzini (Latin: ''Laelius Socinus''; 29 January 1525 – 4 May 1562), was an Italian Renaissance humanist and theologian and, alongside his nephew Fausto Sozzini, founder of the Non-trinitarian Chri ...

and Celio Secondo Curione

Celio Secondo Curione (1 May 1503, in Cirié – 24 November 1569, in Basel) (usual Latin form Caelius Secundus Curio) was an Italian humanist, grammarian, editor and historian, who exercised a considerable influence upon the Italian Reformation. ...

. Concerning the execution of Servetus

Michael Servetus (; es, Miguel Serveto as real name; french: Michel Servet; also known as ''Miguel Servet'', ''Miguel de Villanueva'', ''Revés'', or ''Michel de Villeneuve''; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish th ...

, Castellio wrote: "When Servetus fought with reasons and writings, he should have been repulsed by reasons and writings." He invoked the testimony of Church Fathers like Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

, Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ab ...

and Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

to support freedom of thought

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by ...

, and even used Calvin's own words, written back when he was himself being persecuted by the Catholic Church: "It is unchristian to use arms against those who have been expelled from the Church, and to deny them rights common to all mankind." Asking who is a heretic, he concluded, "I can find no other criterion than that we are all heretics in the eyes of those who do not share our views."

Marius Valkhoff describes Castellio's ''Advice to a Desolate France'' as a pacifist manifesto.

Castellio also can be credited with a huge advance in the promotion of the concept of limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal Theo ...

. He passionately argued for separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

and against the idea of theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

. Arguing that no one is entitled to direct and control another's thought, he stated that authorities should have "no concern with matters of opinion" and concluded: "We can live together peacefully only when we control our intolerance. Even though there will always be differences of opinion from time to time, we can at any rate come to general understandings, can love one another, and can enter the bonds of peace, pending the day when we shall attain unity of faith."

Death

Castellio died in Basel in 1563, and was buried in the tomb of a noble family. His enemies unearthed the body, burned it, and scattered the ashes. Some of his students erected amonument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, his ...

to his memory, which was later destroyed by accident; only the inscription

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

is preserved.Works

*''Dialogi Sacri.'' Geneva 1542, also a much expanded version, Basel 1545 *''.'' Basel 1551 *''De haereticis, an sint persequendi.'' Basel 1554 *''.'' Basel 1555 *''De arte dubitandi.'' *''Conseil à la France désolée.'' 1562 *''De Imitatione Christi.'' 1563References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050306160331/http://www.socinian.org/castellio.html Sebastian Castellio and the Struggle for Freedom of Consciencebr>Sebastian Castellio's Erasmian Liberalism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Castellio, Sebastian 1515 births 1563 deaths People from Ain French Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century French theologians Calvinist pacifists Christianity and politics Cultural critics Moral philosophers 16th-century people from Savoy Philosophers of culture Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of religion Political philosophers Protestant Reformers Religion and politics Secularism Separation of church and state French social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Translators of the Bible into French Translators of the Bible into Latin 16th-century French translators