Caste on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A caste is a fixed

A caste is a fixed

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into four types:

* Classless societies – egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into four types:

* Classless societies – egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the

In Japan's history, social strata based on inherited position rather than personal merit, were rigid and highly formalised in a system called (). At the top were the Emperor and Court nobles (

In Japan's history, social strata based on inherited position rather than personal merit, were rigid and highly formalised in a system called (). At the top were the Emperor and Court nobles ( Marriage between certain classes was generally prohibited. In particular, marriage between daimyo and court nobles was forbidden by the

Marriage between certain classes was generally prohibited. In particular, marriage between daimyo and court nobles was forbidden by the

/ref>

In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such caste systems, he claims, are to be found in

In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such caste systems, he claims, are to be found in

In colonial Spanish America (16th-early 19th centuries), there were legal divisions of society, the Republic of Spaniards (), comprising European whites, African slaves (), and mixed-race , the offspring of unions between whites, blacks, and indigenous. The Republic of Indians () comprised all the various indigenous peoples, now classified in a single category, , by their colonial rulers. In the social and racial hierarchy, European Spaniards were at the apex, with legal rights and privileges. Lower racial groups (Africans, mixed-race castas, and pure indigenous), had fewer legal rights and lower social status. Unlike the rigid caste system in India, in colonial Spanish America there was some fluidity within the social order.

In colonial Spanish America (16th-early 19th centuries), there were legal divisions of society, the Republic of Spaniards (), comprising European whites, African slaves (), and mixed-race , the offspring of unions between whites, blacks, and indigenous. The Republic of Indians () comprised all the various indigenous peoples, now classified in a single category, , by their colonial rulers. In the social and racial hierarchy, European Spaniards were at the apex, with legal rights and privileges. Lower racial groups (Africans, mixed-race castas, and pure indigenous), had fewer legal rights and lower social status. Unlike the rigid caste system in India, in colonial Spanish America there was some fluidity within the social order.

Casteless

Auguste Comte on why and how castes developed across the world – in The Positive Philosophy, Volume 3 (see page 55 onwards)

Robert Merton on Caste and The Sociology of Science

Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age

– Susan Bayly * by Marguerite Abadjian (Archive of the Baltimore Sun)

International Dalit Solidarity Network: An international advocacy group for Dalits

{{Authority control Social status

A caste is a fixed

A caste is a fixed social group

In the social sciences, a social group is defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity. Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties. F ...

into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political ...

: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (endogamy

Endogamy is the cultural practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting any from outside of the group or belief structure as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relatio ...

), follow lifestyles often linked to a particular occupation, hold a ritual status observed within a hierarchy, and interact with others based on cultural notions of exclusion, with certain castes considered as either more pure or more polluted than others. The term "caste" is also applied to morphological groupings in eusocial

Eusociality ( Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping generations wit ...

insects such as ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s, bees, and termites

Termites are a group of detritophagous eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, leaf litter, and soil humus. They are distinguished by their moniliform antennae and the sof ...

.

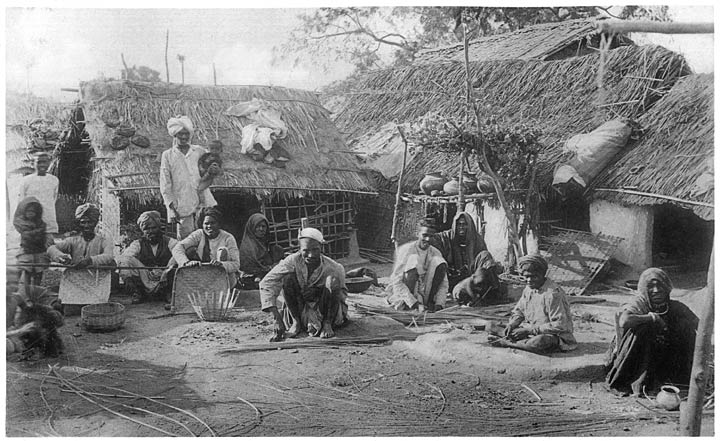

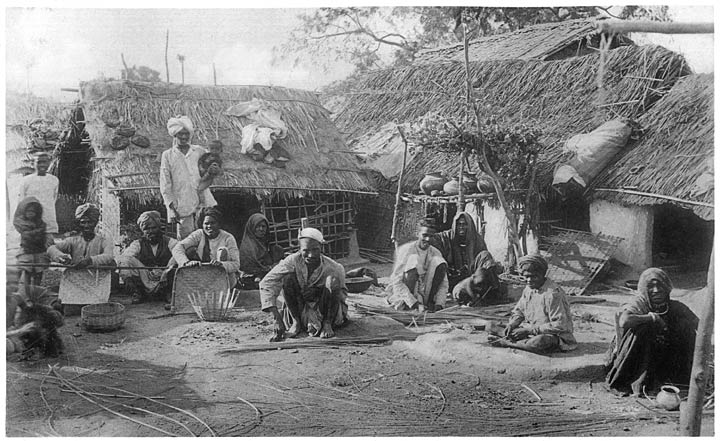

The paradigmatic ethnographic example of caste is the division of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

's Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

society into rigid social groups. Its roots lie in South Asia's ancient history and it still exists; however, the economic significance of the caste system in India

The caste system in India is the paradigmatic ethnographic instance of social classification based on castes. It has its origins in ancient India, and was transformed by various ruling elites in medieval, early-modern, and modern India, espe ...

seems to be declining as a result of urbanisation and affirmative action programs. A subject of much scholarship by sociologists and anthropologists, the Hindu caste system is sometimes used as an analogical basis for the study of caste-like social divisions existing outside Hinduism and India. In colonial Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th and 19th centur ...

, mixed-race ''casta

() is a term which means "Lineage (anthropology), lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish America, Spanish Empire in the Americas, the term also refer ...

s'' were a category within the Hispanic sector but the social order was otherwise fluid.

Etymology

The English word ''caste'' (, ) derives from the Spanish and Portuguese , which, according to theJohn Minsheu

John Minsheu (or Minshew) (1560–1627) was an English Linguistics, linguist and lexicographer.

Biography

He was born and died in London. Little is known about his life. He published some of the earliest dictionaries and grammars of the Spanish ...

's Spanish dictionary (1569), means "race, lineage, tribe or breed". The Portuguese and Spanish word "casta" originated in Gothic "kasts" - "group of animals". The word entered the languages of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

with the sense "type of animal," and soon developed into "race of men" and later "class, condition of men". When the Spanish colonised the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, they used the word to mean a 'clan or lineage'. It was, however, the Portuguese, the first Europeans to reach India by sea in 1498, to first employ in the primary modern sense of the English word 'caste' when they applied it to the thousands of endogamous, hereditary Indian social groups they encountered. The use of the spelling ''caste'', with this latter meaning, is first attested in English in 1613. In the Latin American context, the term ''caste'' is sometimes used to describe the ''casta

() is a term which means "Lineage (anthropology), lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish America, Spanish Empire in the Americas, the term also refer ...

'' system of racial classification, based on whether a person was of pure European, Indigenous or African descent, or some mix thereof, with the different groups being placed in a racial hierarchy; however, despite the etymological connection between the Latin American ''casta'' system and South Asian caste systems (the former giving its name to the latter), it is controversial to what extent the two phenomena are really comparable.

In South Asia

India

Modern India's caste system is based on the superimposition of an old four-fold theoretical classification called varna on the social ethnic grouping called jāti. TheVedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, between the e ...

conceptualised a society as consisting of four types of varnas, or categories: Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

, Kshatriya

Kshatriya () (from Sanskrit ''kṣatra'', "rule, authority"; also called Rajanya) is one of the four varnas (social orders) of Hindu society and is associated with the warrior aristocracy. The Sanskrit term ''kṣatriyaḥ'' is used in the con ...

, Vaishya and Shudra

Shudra or ''Shoodra'' (Sanskrit: ') is one of the four varnas of the Hindu class and social system in ancient India. Some sources translate it into English as a caste, or as a social class. Theoretically, Shudras constituted a class like work ...

, according to the nature of the work of its members. Varna was not an inherited category and the occupation determined the varna. However, a person's Jati is determined at birth and makes them take up that Jati's occupation; members could and did change their occupation based on personal strengths as well as economic, social and political factors. A 2016 study based on the DNA analysis of unrelated Indians determined that endogamous jatis originated during the Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire was an Indian empire during the classical period of the Indian subcontinent which existed from the mid 3rd century to mid 6th century CE. At its zenith, the dynasty ruled over an empire that spanned much of the northern Indian ...

. Today, there are around 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes in India.

From 1901 onwards, for the purposes of the Decennial Census, British authorities in India categorized all Jātis into the four '' Varna'' categories as described in ancient Indian texts. Herbert Hope Risley, the Census Commissioner, noted that "The principle suggested as a basis was that of classification by social precedence as recognized by native public opinion at the present day, and manifesting itself in the facts that particular castes are supposed to be the modern representatives of one or other of the castes of the theoretical Indian system."

''Varna'', as mentioned in ancient Hindu texts, describes society as divided into four categories: Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

s (scholars and yajna priests), Kshatriya

Kshatriya () (from Sanskrit ''kṣatra'', "rule, authority"; also called Rajanya) is one of the four varnas (social orders) of Hindu society and is associated with the warrior aristocracy. The Sanskrit term ''kṣatriyaḥ'' is used in the con ...

s (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (farmers, merchants and artisans) and Shudras (workmen/service providers). Scholars believe that the ''Varnas'' system was never truly operational in society and there is no evidence of it ever being a reality in Indian history. The practical division of the society has been in terms of ''Jatis'' (birth groups), which are not based on any specific religious principle but could vary from ethnic origins to occupations to geographic areas. The ''Jātis'' have been endogamous social groups without any fixed hierarchy but subject to vague notions of rank articulated over time based on lifestyle and social, political, or economic status. Many of India's major empires and dynasties like the Mauryas, Shalivahanas, Chalukyas, Kakatiyas among many others, were founded by people who would have been classified as Shudras, under the ''Varnas'' system, as interpreted by the British. It is well established that by the 9th century, kings from all the four Varnas, including Brahmins and Vaishyas, had occupied the highest seat in the monarchical system in Hindu India, contrary to the Varna theory. Historically the kings and rulers had been called upon to mediate on the ranks of ''Jātis'', which might number in thousands all over the subcontinent and vary by region. In practice, the ''jātis'' are seen to fit into the ''varna'' classes, but the ''varna'' status of ''jātis'' itself was subject to articulation over time.

Starting with the 1901 Census of India led by colonial administrator Herbert Hope Risley, all the ''jātis'' were grouped under the theoretical ''varnas'' categories. According to political scientist Lloyd Rudolph, Risley believed that ''varna'', however ancient, could be applied to all the modern castes found in India, and " emeant to identify and place several hundred million Indians within it." The terms ''varna'' (conceptual classification based on occupation) and ''jāti'' (groups) are two distinct concepts: while ''varna'' is a theoretical four-part division, ''jāti'' (community) refers to the thousands of actual endogamous social groups prevalent across the subcontinent. The classical authors scarcely speak of anything other than the ''varnas'', as it provided a convenient shorthand; but a problem arises when colonial Indologists sometimes confuse the two. Sujata Patel argues that colonial ethnographic practices, frequently in association with Brahmin elites, constructed Indian society as traditional and caste-based. These practices, according to Patel, emphasise the cultural and religious dimensions and downplay economic and political factors.

Upon independence from Britain, the Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India is the supreme legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and ...

listed 1,108 Jatis across the country as Scheduled Castes in 1950, for positive discrimination. This constitution would also ban discrimination of the basis of the caste, though its practice in India remained intact. The Untouchable communities are sometimes called ''Dalit

Dalit ( from meaning "broken/scattered") is a term used for untouchables and outcasts, who represented the lowest stratum of the castes in the Indian subcontinent. They are also called Harijans. Dalits were excluded from the fourfold var ...

'' or '' Harijan'' in contemporary literature. In 2001, Dalits were 16.2% of India's population. Most of the 15 million bonded child workers are from the lowest castes. Independent India has witnessed caste-related violence. In 2005, government recorded approximately 110,000 cases of reported violent acts, including rape and murder, against Dalits.

The socio-economic limitations of the caste system are reduced due to urbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It can also ...

and affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

. Nevertheless, the caste system still exists in endogamy

Endogamy is the cultural practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting any from outside of the group or belief structure as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relatio ...

and patrimony, and politics. The globalisation and economic opportunities from foreign businesses has influenced the growth of India's middle-class population. Some members of the Chhattisgarh Potter Caste Community (CPCC) are middle-class urban professionals and no longer potters unlike the remaining majority of traditional rural potter members. There is persistence of caste in Indian politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

. Caste associations have evolved into caste-based political parties. Political parties and the state perceive caste as an important factor for mobilisation of people and policy development.

Studies by Bhatt and Beteille have shown changes in status, openness, mobility in the social aspects of Indian society. As a result of modern socio-economic changes in the country, India is experiencing significant changes in the dynamics and the economics of its social sphere. While arranged marriages are still the most common practice in India, the internet has provided a network for younger Indians to take control of their relationships through the use of dating apps. This remains isolated to informal terms, as marriage is not often achieved through the use of these apps. Hypergamy

Hypergamy (colloquially referred to as "dating up" or "marrying up") is a term used in social science for the act or practice of a person dating or marrying a spouse of higher social status than themselves.

The antonym "hypogamy" refers to t ...

is still a common practice in India and Hindu culture. Men are expected to marry within their caste, or one below, with no social repercussions. If a woman marries into a higher caste, then her children will take the status of their father. If she marries down, her family is reduced to the social status of their son in law. In this case, the women are bearers of the egalitarian principle of the marriage. There would be no benefit in marrying a higher caste if the terms of the marriage did not imply equality. However, men are systematically shielded from the negative implications of the agreement.

Geographical factors also determine adherence to the caste system. Many Northern villages are more likely to participate in exogamous marriage, due to a lack of eligible suitors within the same caste. Women in North India

North India is a geographical region, loosely defined as a cultural region comprising the northern part of India (or historically, the Indian subcontinent) wherein Indo-Aryans (speaking Indo-Aryan languages) form the prominent majority populati ...

have been found to be less likely to leave or divorce their husbands since they are of a relatively lower caste system, and have higher restrictions on their freedoms. On the other hand, Pahari women, of the northern mountains, have much more freedom to leave their husbands without stigma. This often leads to better husbandry as his actions are not protected by social expectations.

Chiefly among the factors influencing the rise of exogamy is the rapid urbanisation in India experienced over the last century. It is well known that urban centers tend to be less reliant on agriculture and are more progressive as a whole. As India's cities boomed in population, the job market grew to keep pace. Prosperity and stability were now more easily attained by an individual, and the anxiety to marry quickly and effectively was reduced. Thus, younger, more progressive generations of urban Indians are less likely than ever to participate in the antiquated system of arranged endogamy.

India has also implemented a form of Affirmative Action, locally known as "reservation groups". Quota system jobs, as well as placements in publicly funded colleges, hold spots for the 8% of India's minority, and underprivileged groups. As a result, in states such as Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

or those in the north-east, where underprivileged populations predominate, over 80% of government jobs are set aside in quotas. In education, colleges lower the marks necessary for the Dalits to enter.

Nepal

The Nepali caste system resembles in some respects the Indian ''jāti'' system, with numerous ''jāti'' divisions with a ''varna'' system superimposed. Inscriptions attest the beginnings of a caste system during the Licchavi period. Jayasthiti Malla (1382–1395) categorised Newars into 64 castes (Gellner 2001). A similar exercise was made during the reign of Mahindra Malla (1506–1575). The Hindu social code was later set up in the Gorkha Kingdom by Ram Shah (1603–1636).Pakistan

McKim Marriott claims a social stratification that is hierarchical, closed, endogamous and hereditary is widely prevalent, particularly in western parts of Pakistan. Frederik Barth in his review of this system of social stratification in Pakistan suggested that these are castes.Sri Lanka

The caste system in Sri Lanka is a division of society into strata, influenced by the textbook ''jāti'' system found in India. Ancient Sri Lankan texts such as the Pujavaliya, Sadharmaratnavaliya and Yogaratnakaraya and inscriptional evidence show that the above hierarchy prevailed throughout the feudal period. The repetition of the same caste hierarchy even as recently as the 18th century, in the Kandyan-period Kadayimpoth – Boundary books as well indicates the continuation of the tradition right up to the end of Sri Lanka's monarchy.Rest of Asia

Southeast Asia

Indonesia

Bali

Bali (English:; Balinese language, Balinese: ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller o ...

nese caste structure has been described as being based either on three categories—the noble triwangsa (thrice born), the middle class of ''dwijāti'' (twice born), and the lower class of ''ekajāti'' (once born), much similar to the traditional Indian BKVS social stratification — or on four castes

*Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

as – priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

* Satrias – knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

hood

* Wesias – commerce

Commerce is the organized Complex system, system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered large-scale exchange (distribution through Financial transaction, transactiona ...

* Sudras – servitude

The Brahmana caste was further subdivided by Dutch ethnographers into two: Siwa and Buda. The Siwa caste was subdivided into five: Kemenuh, Keniten, Mas, Manuba and Petapan. This classification was to accommodate the observed marriage between higher-caste Brahmana men with lower-caste women. The other castes were similarly further sub-classified by 19th-century and early-20th-century ethnographers based on numerous criteria ranging from profession, endogamy or exogamy or polygamy, and a host of other factors in a manner similar to ''castas'' in Spanish colonies such as Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, and caste system studies in British colonies such as India.

Philippines

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into four types:

* Classless societies – egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into four types:

* Classless societies – egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the Mangyan

Mangyan is the generic name for the eight indigenous groups found in Mindoro each with its own tribal name, language, and customs. The total population may be around 280,001, but official statistics are difficult to determine under the condi ...

and the Kalanguya peoples.

* Warrior societies – societies where a distinct warrior class exists, and whose membership depends on martial prowess. Examples include the Mandaya, Bagobo, Tagakaulo, and B'laan peoples who had warriors called the ''bagani'' or ''magani''. Similarly, in the Cordillera highlands of Luzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

, the Isneg and Kalinga peoples refer to their warriors as ''mengal'' or ''maingal''. This society is typical for head-hunting

Headhunting is the practice of human hunting, hunting a human and human trophy collecting, collecting the decapitation, severed human head, head after killing the victim. More portable body parts (such as ear, rhinotomy, nose, or scalping, scal ...

ethnic groups or ethnic groups which had seasonal raids ('' mangayaw'') into enemy territory.

* Petty plutocracies – societies which have a wealthy class based on property and the hosting of periodic prestige feasts. In some groups, it was an actual caste whose members had specialised leadership roles, married only within the same caste, and wore specialised clothing. These include the ''kadangyan'' of the Ifugao, Bontoc, and Kankanaey peoples, as well as the ''baknang'' of the Ibaloi people. In others, though wealth may give one prestige and leadership qualifications, it was not a caste per se.

*Principalities – societies with an actual ruling class and caste systems determined by birthright. Most of these societies are either Indianized or Islamized to a degree. They include the larger coastal ethnic groups like the Tagalog, Kapampangan, Visayan, and Moro societies. Most of them were usually divided into four to five caste systems with different names under different ethnic groups that roughly correspond to each other. The system was more or less feudalistic, with the ''datu'' ultimately having control of all the lands of the community. The land is subdivided among the enfranchised classes, the ''sakop'' or ''sa-op'' (vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s, lit. "those under the power of another"). The castes were hereditary, though they were not rigid. They were more accurately a reflection of the interpersonal political relationships, a person is always the follower of another. People can move up the caste system by marriage, by wealth, or by doing something extraordinary; and conversely they can be demoted, usually as criminal punishment or as a result of debt. Shamans are the exception, as they are either volunteers, chosen by the ranking shamans, or born into the role by innate propensity for it. They are enumerated below from the highest rank to the lowest:

:* Royalty – ( Visayan: '' kadatoan'') the ''datu

''Datu'' is a title which denotes the rulers (variously described in historical accounts as chiefs, sovereign princes, and monarchs) of numerous Indigenous peoples throughout the Philippine archipelago. The title is still used today, though no ...

'' and immediate descendants. They are often further categorised according to purity of lineage. The power of the ''datu'' is dependent on the willingness of their followers to render him respect and obedience. Most roles of the datu were judicial and military. In case of an unfit ''datu'', support may be withdrawn by his followers. ''Datu'' were almost always male, though in some ethnic groups like the Banwaon people, the female shaman ('' babaiyon'') co-rules as the female counterpart of the ''datu''.

:* Nobility – (Visayan: '' tumao''; Tagalog: ''maginoo

The Tagalog ''maginoo'', the Kapampangan ''ginu'', and the Visayan ''tumao'' were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the ''tumao'' were further distinguished from the immediat ...

''; Kapampangan ''ginu''; Tausug: ''bangsa mataas'') the ruling class, either inclusive of or exclusive of the royal family. Most are descendants of the royal line or gained their status through wealth or bravery in battle. They owned lands and subjects, from whom they collected taxes.

:* Shamans – (Visayan: ''babaylan''; Tagalog: ''katalonan'') the spirit mediums, usually female or feminised men. While they were not technically a caste, they commanded the same respect and status as nobility.

:* Warriors – (Visayan: ''timawa

The ''timawa'' were the feudalism, feudal warrior class of the ancient Visayan people, Visayan societies of the Philippines. They were regarded as higher than the ''uripon'' (commoners, serfs, and slaves) but below the ''tumao'' (royal nobility ...

''; Tagalog: '' maharlika'') the martial class. They could own land and subjects like the higher ranks, but were required to fight for the ''datu'' in times of war. In some Filipino ethnic groups, they were often tattooed extensively to record feats in battle and as protection against harm. They were sometimes further subdivided into different classes, depending on their relationship with the ''datu''. They traditionally went on seasonal raids on enemy settlements.

:* Commoners and slaves – (Visayan, Maguindanao: '' ulipon''; Tagalog: '' alipin''; Tausug: ''kiapangdilihan''; Maranao: ''kakatamokan'') – the lowest class composed of the rest of the community who were not part of the enfranchised classes. They were further subdivided into the commoner class who had their own houses, the servants who lived in the houses of others, and the slaves who were usually captives from raids, criminals, or debtors. Most members of this class were equivalent to the European serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

class, who paid taxes and can be conscripted to communal tasks, but were more or less free to do as they please.

East Asia

Tibet

There is significant controversy over the social classes of Tibet, especially with regards to the serfdom in Tibet controversy. There were three main feudal social groups inTibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

prior to 1959, namely ordinary laypeople (''mi ser'' in Tibetan), lay nobility (''sger pa''), and monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

s.

has put forth the argument that pre-1950s Tibetan society was functionally a caste system, in contrast to previous scholars who defined the Tibetan social class system as similar to European feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

, as well as non-scholarly western accounts which seek to romanticise a supposedly egalitarian ancient Tibetan society.

Japan

kuge

The was a Japanese Aristocracy (class), aristocratic Social class, class that dominated the Japanese Imperial Court in Kyoto. The ''kuge'' were important from the establishment of Kyoto as the capital during the Heian period in the late 8th ce ...

), together with the Shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, except during parts of the Kamak ...

and daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

.

Older scholars believed that there were of "samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

, peasants (''hyakushō''), craftsmen, and merchants ('' chōnin'')" under the daimyo, with 80% of peasants under the 5% samurai class, followed by craftsmen and merchants. However, various studies have revealed since about 1995 that the classes of peasants, craftsmen, and merchants under the samurai are equal, and the old hierarchy chart has been removed from Japanese history textbooks. In other words, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants are not a social pecking order, but a social classification.

Marriage between certain classes was generally prohibited. In particular, marriage between daimyo and court nobles was forbidden by the

Marriage between certain classes was generally prohibited. In particular, marriage between daimyo and court nobles was forbidden by the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

because it could lead to political maneuvering. For the same reason, marriages between daimyo and high-ranking hatamoto

A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the Shōgun, shogunates in History of Japan, Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred ...

of the samurai class required the approval of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was also forbidden for a member of the samurai class to marry a peasant, craftsman, or merchant, but this was done through a loophole in which a person from a lower class was adopted into the samurai class and then married. Since there was an economic advantage for a poor samurai class person to marry a wealthy merchant or peasant class woman, they would adopt a merchant or peasant class woman into the samurai class as an adopted daughter and then marry her. Samurai had the right to strike and even kill with their sword anyone of a lower class who compromised their honour

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself ...

.Kirisute-gomen - Samurai World/ref>

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

had its own untouchable caste, shunned and ostracised, historically referred to by the insulting term ''eta'', now called ''burakumin

The are a social grouping of Japanese people descended from members of the feudal class associated with , mainly those with occupations related to death such as executioners, gravediggers, slaughterhouse workers, butchers, and tanners. Bura ...

''. While modern law has officially abolished the class hierarchy, there are reports of discrimination against the ''buraku'' or ''burakumin'' underclasses. The ''burakumin'' are regarded as "ostracised". The ''burakumin'' are one of the main minority groups in Japan, along with the Ainu of Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

and those of Korean or Chinese descent.

Korea

The baekjeong () were an "untouchable" outcaste of Korea. The meaning today is that of butcher. It originates in the Khitan invasion of Korea in the 11th century. The defeated Khitans who surrendered were settled in isolated communities throughout Goryeo to forestall rebellion. They were valued for their skills in hunting, herding, butchering, and making of leather, common skill sets among nomads. Over time, their ethnic origin was forgotten, and they formed the bottom layer of Korean society. In 1392, with the foundation of the ConfucianJoseon dynasty

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

, Korea systemised its own native class system. At the top were the two official classes, the Yangban, which literally means "two classes". It was composed of scholars () and warriors (). Scholars had a significant social advantage over the warriors. Below were the (: literally "middle people"). This was a small class of specialised professions such as medicine, accounting, translators, regional bureaucrats, etc. Below that were the (: literally 'commoner'), farmers working their own fields. Korea also had a serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

population known as the ''nobi''. The nobi population could fluctuate up to about one third of the population, but on average the nobi made up about 10% of the total population. In 1801, the vast majority of government nobi were emancipated, and by 1858 the nobi population stood at about 1.5% of the total population of Korea. The hereditary nobi system was officially abolished around 1886–87 and the rest of the nobi system was abolished with the Gabo Reform

The Kabo Reform () describes a series of sweeping reforms suggested to the government of Korea, beginning in 1894 and ending in 1896 during the reign of Gojong of Korea in response to the Donghak Peasant Revolution. Historians debate the degre ...

of 1894, but traces remained until 1930.

The opening of Korea to foreign Christian mission

A Christian mission is an organized effort to carry on evangelism, in the name of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries. Sometimes individuals are sent and a ...

ary activity in the late 19th century saw some improvement in the status of the . However, everyone was not equal under the Christian congregation, and even so protests erupted when missionaries tried to integrate into worship, with non- finding this attempt insensitive to traditional notions of hierarchical advantage. Around the same time, the began to resist open social discrimination. They focused on social and economic injustices affecting them, hoping to create an egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

Korean society. Their efforts included attacking social discrimination by upper class, authorities, and "commoners", and the use of degrading language against children in public schools.

With the Gabo reform

The Kabo Reform () describes a series of sweeping reforms suggested to the government of Korea, beginning in 1894 and ending in 1896 during the reign of Gojong of Korea in response to the Donghak Peasant Revolution. Historians debate the degre ...

of 1896, the class system of Korea was officially abolished. Following the collapse of the Gabo government, the new cabinet, which became the Gwangmu government after the establishment of the Korean Empire

The Korean Empire, officially the Empire of Korea or Imperial Korea, was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by King Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire lasted until the Japanese annexation of Korea in August 1910.

Dur ...

, introduced systematic measures for abolishing the traditional class system. One measure was the new household registration system, reflecting the goals of formal social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and social servi ...

, which was implemented by the loyalists' cabinet. Whereas the old registration system signified household members according to their hierarchical social status, the new system called for an occupation.

While most Koreans by then had surnames and even , although still substantial number of , mostly consisted of serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

and slaves, and untouchables did not. According to the new system, they were then required to fill in the blanks for surname in order to be registered as constituting separate households. Instead of creating their own family name, some appropriated their masters' surname, while others simply took the most common surname and its in the local area. Along with this example, activists within and outside the Korean government had based their visions of a new relationship between the government and people through the concept of citizenship, employing the term ("people") and later, ("citizen").

North Korea

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea reported that "Every North Korean citizen is assigned a heredity-based class and socio-political rank over which the individual exercises no control but which determines all aspects of his or her life." Called '' Songbun'', Barbara Demick describes this "class structure" as an updating of the hereditary "caste system", a combination ofConfucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

and Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. It originated in 1946 and was entrenched by the 1960s, and consisted of 53 categories ranging across three classes: loyal, wavering, and impure. The privileged "loyal" class included members of the Korean Workers' Party and Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

officers' corps, the wavering class included peasants, and the impure class included collaborators with Imperial Japan and landowners. She claims that a bad family background is called "tainted blood", and that by law this "tainted blood" lasts three generations.

West Asia

Kurdistan

= Yazidis

= There are three hereditary groups, often called castes, in Yazidism. Membership in the Yazidi society and a caste is conferred by birth. Pîrs and Sheikhs are the priestly castes, which are represented by many sacred lineages (). Sheikhs are in charge of both religious and administrative functions and are divided into three endogamous houses, Şemsanî, Adanî and Qatanî who are in turn divided into lineages. The Pîrs are in charge of purely religious functions and traditionally consist of 40 lineages or clans, but approximately 90 appellations of Pîr lineages have been found, which may have been a result of new sub-lineages arising and number of clans increasing over time due to division as Yazidis settled in different places and countries. Division could occur in one family, if there were a few brothers in one clan, each of them could become the founder of their own Pîr sub-clan (). Mirîds are the lay caste and are divided intotribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

, who are each affiliated to a Pîr and a Sheikh priestly lineage assigned to the tribe.

Iran

Pre-IslamicSassanid

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

society was immensely complex, with separate systems of social organisation governing numerous different groups within the empire.Nicolle, p. 11 Historians believe society comprised four social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

es, which linguistic analysis indicates may have been referred to collectively as "pistras". The classes, from highest to lowest status, were priests (), warriors (), secretaries (), and commoners ().

Yemen

InYemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

there exists a hereditary caste, the Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

n-descended Al-Akhdam who are kept as perennial manual workers. Estimates put their number at over 3.5 million residents who are discriminated, out of a total Yemeni population of around 22 million.

Africa

Various sociologists have reported caste systems in Africa. The specifics of the caste systems have varied in ethnically and culturally diverse Africa; however, the following features are common – it has been a closed system of social stratification, the social status is inherited, the castes are hierarchical, certain castes are shunned while others are merely endogamous and exclusionary. In some cases, concepts of purity and impurity by birth have been prevalent in Africa. In other cases, such as the '' Nupe'' of Nigeria, the '' Beni Amer'' of East Africa, and the '' Tira'' of Sudan, the exclusionary principle has been driven by evolving social factors.West Africa

Among the Igbo ofNigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

– especially Enugu, Anambra, Imo, Abia, Ebonyi, Edo and Delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta"), the fourth letter in the Latin alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* Delta Air Lines, a major US carrier ...

states of the country – scholar Elijah Obinna finds that the Osu caste system has been and continues to be a major social issue. The Osu caste is determined by one's birth into a particular family irrespective of the religion practised by the individual. Once born into Osu caste, this Nigerian person is an outcast, shunned and ostracised, with limited opportunities or acceptance, regardless of his or her ability or merit. Obinna discusses how this caste system-related identity and power is deployed within government, Church and indigenous communities.

The ''osu'' class systems of eastern Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and southern Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

are derived from indigenous religious beliefs and discriminate against the "Osus" people as "owned by deities" and outcasts.

The Songhai economy was based on a caste system. The most common were metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters. Lower caste participants consisted of mostly non-farm working immigrants, who at times were provided special privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen and direct descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by freemen and traders.

In a review of social stratification systems in Africa, Richter reports that the term caste has been used by French and American scholars to many groups of West African artisans. These groups have been described as inferior, deprived of all political power, have a specific occupation, are hereditary and sometimes despised by others. Richter illustrates caste system in Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

, with six sub-caste categories. Unlike other parts of the world, mobility is sometimes possible within sub-castes, but not across caste lines. Farmers and artisans have been, claims Richter, distinct castes. Certain sub-castes are shunned more than others. For example, exogamy is rare for women born into families of woodcarvers.

Similarly, the Mandé societies in Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

, Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

, Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

have social stratification systems that divide society by ethnic ties. The Mande class system regards the ''jonow'' slaves as inferior. Similarly, the Wolof in Senegal is divided into three main groups, the ''geer'' (freeborn/nobles), ''jaam'' (slaves and slave descendants) and the underclass ''neeno''. In various parts of West Africa, Fulani societies also have class divisions. Other castes include ''Griots'', ''Forgerons'', and ''Cordonniers''.

Tamari has described endogamous castes of over fifteen West African peoples, including the Tukulor, Songhay, Dogon, Senufo, Minianka, Moors, Manding, Soninke, Wolof, Serer, Fulani, and Tuareg. Castes appeared among the ''Malinke'' people no later than 14th century, and was present among the ''Wolof'' and ''Soninke'', as well as some ''Songhay'' and ''Fulani'' populations, no later than 16th century. Tamari claims that wars, such as the ''Sosso-Malinke'' war described in the ''Sunjata'' epic, led to the formation of blacksmith and bard castes among the people that ultimately became the Mali empire.

As West Africa evolved over time, sub-castes emerged that acquired secondary specialisations or changed occupations. Endogamy was prevalent within a caste or among a limited number of castes, yet castes did not form demographic isolates according to Tamari. Social status according to caste was inherited by off-springs automatically; but this inheritance was paternal. That is, children of higher caste men and lower caste or slave concubines would have the caste status of the father.

Central Africa

Ethel M. Albert in 1960 claimed that the societies inCentral Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

were caste-like social stratification systems. Similarly, in 1961, Maquet notes that the society in Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

and Burundi

Burundi, officially the Republic of Burundi, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is located in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa, with a population of over 14 million peop ...

can be best described as castes. The Tutsi

The Tutsi ( ), also called Watusi, Watutsi or Abatutsi (), are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. They are a Bantu languages, Bantu-speaking ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi ( ...

, noted Maquet, considered themselves as superior, with the more numerous Hutu and the least numerous Twa regarded, by birth, as respectively, second and third in the hierarchy of Rwandese society. These groups were largely endogamous, exclusionary and with limited mobility.

Horn of Africa

In Ethiopia, there have been a number of studies of castes. Broad studies of castes have been written by Alula Pankhurst, who has published a study of caste groups in SW Ethiopia. and a later volume by Dena Freeman writing with Pankhurst. In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such caste systems, he claims, are to be found in

In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such caste systems, he claims, are to be found in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

in communities such as the Gurage and Konso

Karat is a town in south-western Ethiopia and the capital of the Konso Zone in the new South Ethiopia Regional State. Situated 20 km north of the Sagan River at an elevation of , it is also called Pakawle by some of the neighboring inhabita ...

. He then presents the Dime of Southwestern Ethiopia, amongst whom there operates a system which Todd claims can be unequivocally labelled as caste system. The Dime have seven castes whose size varies considerably. Each broad caste level is a hierarchical order that is based on notions of purity, non-purity and impurity. It uses the concepts of defilement to limit contacts between caste categories and to preserve the purity of the upper castes. These caste categories have been exclusionary, endogamous and the social identity inherited.

Among the Kafa, there were also traditionally groups labelled as castes. "Based on research done before the Derg regime, these studies generally presume the existence of a social hierarchy similar to the caste system. At the top of this hierarchy were the Kafa, followed by occupational groups including blacksmiths (Qemmo), weavers (Shammano), bards (Shatto), potters, and tanners (Manjo). In this hierarchy, the Manjo were commonly referred to as hunters, given the lowest status equal only to slaves."

The Borana Oromo of southern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

also have a class system, wherein the Wata, an acculturated hunter-gatherer group, represent the lowest class. Though the Wata today speak the Oromo language

Oromo, historically also called Galla, is an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic branch, primarily spoken by the Oromo people, native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia; and northern Kenya. It is used as a lingua franca in Oromia an ...

, they have traditions of having previously spoken another language before adopting Oromo.

The traditionally nomadic Somali people

The Somali people (, Wadaad: , Arabic: ) are a Cushitic ethnic group and nation native to the Somali Peninsula. who share a common ancestry, culture and history.

The East Cushitic Somali language is the shared mother tongue of ethnic Som ...

are divided into clans, wherein the Rahanweyn agro-pastoral clans and the occupational clans such as the Madhiban were traditionally sometimes treated as outcasts. As Gabooye, the Madhiban along with the Yibir and Tumaal (collectively referred to as ''sab'') have since obtained political representation within Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

, and their general social status has improved with the expansion of urban centers.

Europe

Basque Country

For centuries, through the modern times, the majority regarded Cagots who lived primarily in the Basque region of France and Spain as an inferior caste, and a group of untouchables. While they had the same skin color and religion as the majority, in the churches they had to use segregated doors, drink from segregated fonts, and receive communion on the end of long wooden spoons. It was a closed social system. The socially isolated Cagots were endogamous, and chances of social mobility non-existent.United Kingdom

In July 2013, the UK government announced its intention to amend the Equality Act 2010, to "introduce legislation on caste, including any necessary exceptions to the caste provisions, within the framework of domestic discrimination law". Section 9(5) of the Equality Act 2010 provides that "a Minister may by order amend the statutory definition of race to include caste and may provide for exceptions in the Act to apply or not to apply to caste". From September 2013 to February 2014, Meena Dhanda led a project on "Caste in Britain" for the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).Americas

Latin America

In colonial Spanish America (16th-early 19th centuries), there were legal divisions of society, the Republic of Spaniards (), comprising European whites, African slaves (), and mixed-race , the offspring of unions between whites, blacks, and indigenous. The Republic of Indians () comprised all the various indigenous peoples, now classified in a single category, , by their colonial rulers. In the social and racial hierarchy, European Spaniards were at the apex, with legal rights and privileges. Lower racial groups (Africans, mixed-race castas, and pure indigenous), had fewer legal rights and lower social status. Unlike the rigid caste system in India, in colonial Spanish America there was some fluidity within the social order.

In colonial Spanish America (16th-early 19th centuries), there were legal divisions of society, the Republic of Spaniards (), comprising European whites, African slaves (), and mixed-race , the offspring of unions between whites, blacks, and indigenous. The Republic of Indians () comprised all the various indigenous peoples, now classified in a single category, , by their colonial rulers. In the social and racial hierarchy, European Spaniards were at the apex, with legal rights and privileges. Lower racial groups (Africans, mixed-race castas, and pure indigenous), had fewer legal rights and lower social status. Unlike the rigid caste system in India, in colonial Spanish America there was some fluidity within the social order.

United States

In the opinion of W. Lloyd Warner, discrimination in the Southern United States in the 1930s against Blacks was similar to Indian castes in such features as residential segregation and marriage restrictions. In her 2020 book '' Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents'', journalist Isabel Wilkerson used caste as an analogy to understand racial discrimination in the United States. Gerald D. Berreman contrasted the differences between discrimination in the United States and India. In India, there are complex religious features which make up the system, whereas in the United States race and color are the basis for differentiation. The caste systems in India and the United States have higher groups which desire to retain their positions for themselves and thus perpetuate the two systems. The process of creating a homogenized society by social engineering in both India and the Southern US has created other institutions that have made class distinctions among different groups evident. Anthropologist James C. Scott elaborates on how "globalcapitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

is perhaps the most powerful force for homogenization, whereas the state may be the defender of local difference and variety in some instances". The caste system, a relic of feudalistic economic systems, emphasizes differences between socio-economic classes that are obviated by openly free market capitalistic economic systems, which reward individual initiative, enterprise, merit, and thrift, thereby creating a path for social mobility. When the feudalistic slave economy of the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

was dismantled, Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

and acts of domestic terrorism committed by white supremacists prevented many industrious African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

from participating in the formal economy and achieving economic success on parity with their white peers, or destroying that economic success in instances where it was achieved, such as Black Wall Street, with only rare but commonly touted exceptions to lasting personal success such as Maggie Walker, Annie Malone, and Madame C.J. Walker. Parts of the United States are sometimes divided by race and class status despite the national narrative of integration.

A survey on caste discrimination conducted by Equality Labs found 67% of Indian Dalits living in the US reporting that they faced caste-based harassment at the workplace, and 27% reporting verbal or physical assault based on their caste. However, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) is a nonpartisan international affairs think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C., with operations in Europe, South Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East, as well as the United States. Foun ...

study in 2021 criticizes Equality Labs findings and methodology noting Equality Labs study "relied on a nonrepresentative snowball sampling method to recruit respondents. Furthermore, respondents who did not disclose a caste identity were dropped from the data set. Therefore, it is likely that the sample does not fully represent the South Asian American population and could skew in favor of those who have strong views about caste. While the existence of caste discrimination in India is incontrovertible, its precise extent and intensity in the United States can be contested".

In 2023, Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

became the first city in the United States to ban discrimination based on caste.

Racial casteism

Racial casteism is a term used to identify the relationship between caste, race, and colorism. In modern-day India, the caste system has expanded to include groups and identities from diasporic groups as well such as the Africana Siddis and Kaffirs. Siddis make up 40,000 of India's vast population and are perceived as untouchables under the caste framework.This categorization is paired with anti-black ideology in the country, that is often adapted by broader uses of the term caste in western countries, most notably the United States. Like the Siddis, Africana casteSri Lanka Kaffirs

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs (cafrinhas in Portuguese language, Portuguese, කාපිරි ''kāpiriyō'' in Sinhalese language, Sinhala, and காப்பிலி ''kāppili'' in Tamil language, Tamil) are an ethnic group in Sri Lanka who are pa ...

make up a small minority of the population with scholars noting that the exact number is hard to determine due to exclusion and lack of recognition from the government. Siddis and Kaffirs are considered untouchables due to their darker skin color alongside other physical factors that distinguish the group as lower caste.

The migration of Africana groups such as the Siddis and Kaffirs to South Asia is widely considered to be a result of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade, initiated by Muslim Arabs. During the trade, enslaved Africans were often brought as court servants, herbalists, midwives, or as bonded labor. The limited awareness of these groups can be attributed to caste-ideology fueled from this trade.

The racial understanding of caste has largely been debated by scholars, with some like Dr. B. R. Ambedkar arguing that caste differences between higher caste Aryans and lower cast native-Indians being more due to religious factors. While the term remains contended, it is widely understood that this racial assessment is based on the way lower-caste people are treated. Africana diasporic groups who do not fit the caste system reflected by the scheduled tribe are thus considered inferior for their darker skin and grouped in with the untouchables. Since caste is inherited at birth and is inflexible to change throughout a lifetime, this can lead to a racial caste system where colorism largely influences the mobility one has in their lifetime. Terminology shifted away from race-conscious terms in South Asian antiquity, where Aryans had pre-conceived social hierarchies built off of race, to a caste framework during Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

's rise in the third century BCE.

Racial caste is embedded in the institutions that make up South Asia, particularly its governing bodies. When it comes to the electorate of India, voter preference is often based on race, caste, religion, alongside other attributing physical and political factors. This power imbalance alongside the rigid nature of caste can work against those of darker skin complexion to hold positions of power.

Caste and higher education

The foundational divisions of caste have historically been seen as a determining factor in one's skills and career prospects. Today, many people perceive higher education as a means of achieving their own professional goals, but there are still methods based on caste assumptions used to keep lower caste out of universities. This leads to their exclusion from the potential to be part of higher-paying jobs that are perceived as more elite. This social expectation and prevention of access to education and opportunity have elongated the struggle for financial and social equity amongst people from scheduled tribes and castes. Affirmative Action has been a global phenomenon to develop more spaces in politics, jobs, and education for people from historically disadvantaged backgrounds, which has led to the reservation system being applied to universities. Even with these regulations, caste nevertheless remains a largely determining factor in the university system inIndia

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. The guarantee of admittance to a certain proportion of people from oppressed castes is not enough to deal with the implications of divisions in higher education. For example, the reservation percentage can vary by state but is generally around 15% for Scheduled Castes, but 2019–20 data shows most universities miss this mark. Across the board, there is an average of 14.7% of scheduled caste students, meaning many universities are at a far lower rate than legislated. These reservation systems have backlash from upper caste groups, who claim that people are only admitted due to their caste status, as opposed to merit, in a similar argument playing out to affirmative action in the United States.

Reservation policies constitute a first step in providing access to admittance into higher education opportunities but do not overcome the overarching challenge of casteism. Caste-based discrimination and social stigma can still affect the experiences of students from marginalized communities in academic institutions. Universities are a crucial place of integration and moving to offer equitable opportunity beyond just attendance, but implementing protective policies to ensure students can be successful. Attendance at university has already been shown to impact how people view caste and has the potential to shape equity building beyond the current interpersonal and systemic relationship.

Several forms of discrimination manifest in universities:

Social Discrimination: Students from marginalized castes face social discrimination, exclusion, and/or isolation on campuses. This affects their general educational experience and mental well-being. Numerous cases of harassment and bullying based on caste lines have been reported, with drastic consequences for the victims, but often none for the perpetrators. This promotes a hostile environment for students and hampers their ability to engage positively in the academic community.

"When I was enrolled for an undergraduate course, I was vocal about his Dalit identity and vouched for the rights of Dalits and marginalized sections. Most of my upper-caste mates were against reservation. I was always typecast, stereotyped and even labeled with derogatory nicknames," Nishat Kabir, who is studying film at Ambedkar University in New Delhi, told Anadolu Agency.

Campus Facilities: Discrimination can also be observed in access to living facilities, food services, and other campus amenities. Students from marginalized castes may encounter difficulties in availing of these services without bias, and the living arrangements are often internally segregated.