Carolingian-dynasty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

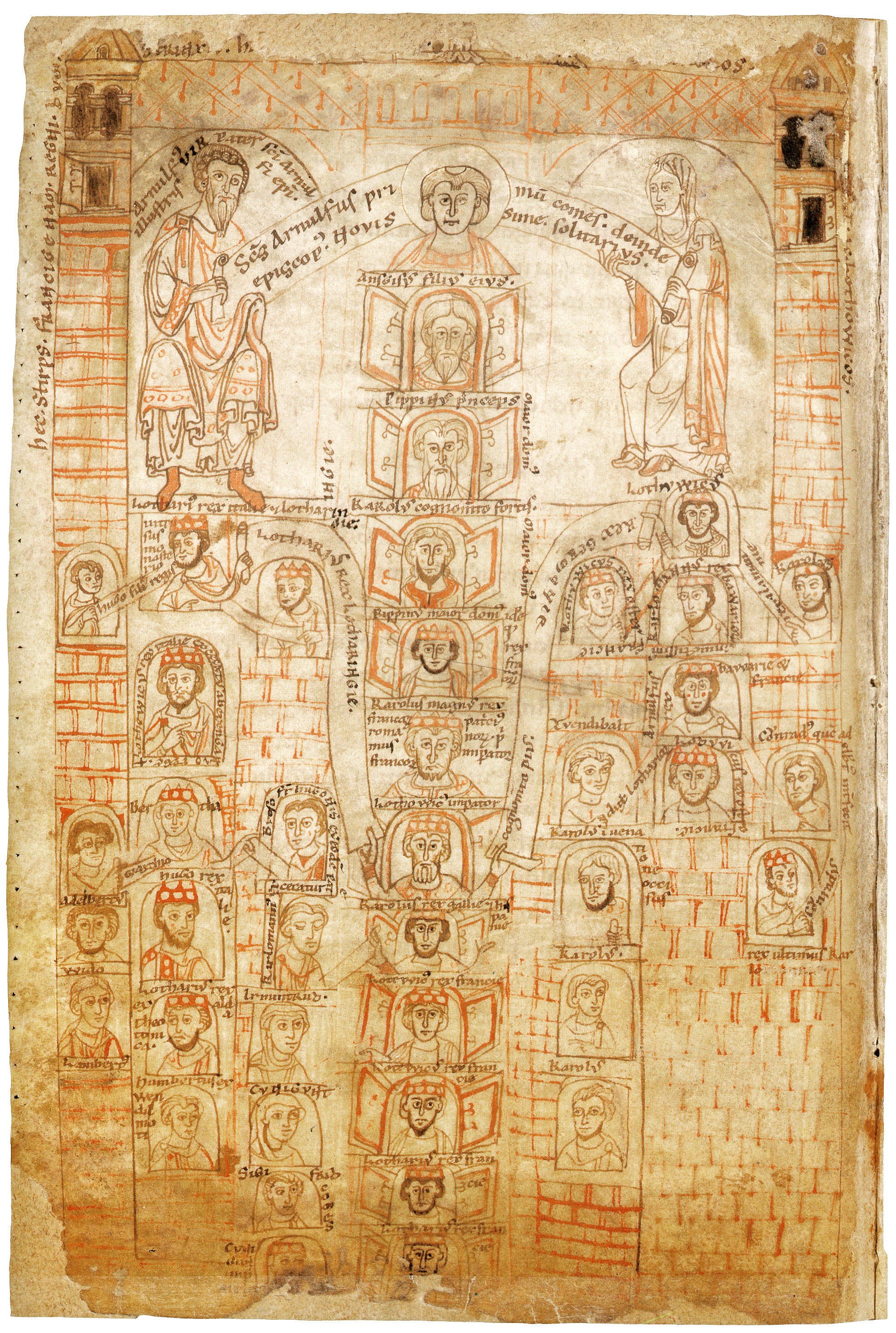

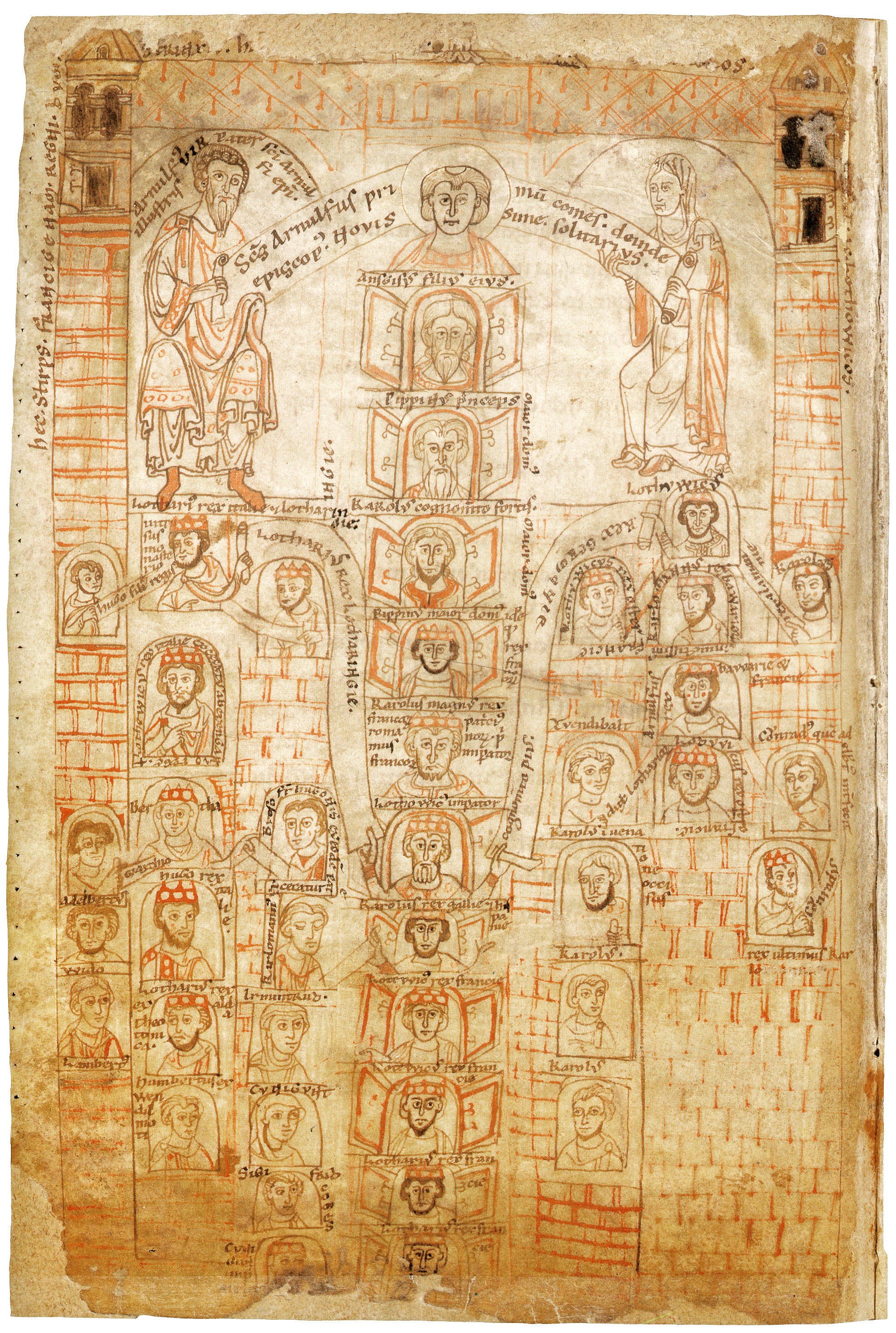

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power in the 8th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and ''

The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne, Pepin's son. Charlemagne was crowned Emperor by

The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne, Pepin's son. Charlemagne was crowned Emperor by

The Carolingian dynasty has five distinct branches:

#The Lombard branch, or Vermandois branch, or Herbertians, descended from

The Carolingian dynasty has five distinct branches:

#The Lombard branch, or Vermandois branch, or Herbertians, descended from

The historian

The historian

Vita Hludovici imperatoris

', ed. G. Pertz, ch. 2, in Mon. Gen. Hist. Scriptores, II, 608. * Reuter, Timothy (trans.)

'. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992. *

Vita Karoli Magni

'. Translated by Samuel Epes Turner. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1880. * Charles Cawley & FM

fmg.ca, 2006–15 * Charles Cawley & FM

fmg.ca, 2006–15

dux et princeps Francorum

The title Duke of the Franks ( la, dux Francorum) has been used for three different offices, always with "duke" implying military command and "prince" implying something approaching sovereign or regalian rights. The term "Franks" may refer to an ...

'' hereditary, and becoming the ''de facto'' rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the Merovingian throne. In 751 the Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Germanic Franks was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and the aristocracy, and Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

, son of Martel, was crowned King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Charlemagne as the first Emperor of the Romans in the West in over three centuries. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Name

The Carolingian dynasty takes its name from ''Carolus'', the Latinised name of Charles Martel, ''de facto'' ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. The name "Carolingian" ( Medieval Latin ''karolingi'', an altered form of an unattested Old High German word ''karling'' or ''kerling'', meaning "descendant of Charles" cf. MHG ''kerlinc'') means "the family of Charles."History

Origins

Pippin I & Arnulf of Metz (613–645)

The Carolingian line began first with two important rival Frankish families, thePippinids

The Pippinids and the Arnulfings were two Frankish aristocratic families from Austrasia during the Merovingian period. They dominated the office of mayor of the palace after 687 and eventually supplanted the Merovingians as kings in 751, founding ...

and Arnulfings, whose destinies became intermingled in the early 7th century. Both men came from noble backgrounds on the western borders of the Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

territory between the Meuse and Moselle

The Moselle ( , ; german: Mosel ; lb, Musel ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a bank (geography), left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it jo ...

rivers, north of Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

.

The first two figures Pippin I of Landen and Arnulf of Metz, from whom historians have taken the family names, both first appeared in the fourth book of the '' Continuations of Fredegar'' as advisers to Chlotar II of Neustria, who ‘incited’ revolt against King Theuderic II and Brunhild of Austrasia in 613. Through shared interests, Pippin and Arnulf allied their families through the marriage of Pippin's daughter Begga

Saint Begga (also Begue, Begge) (b. 613 – d. 17 December 693 AD) was the daughter of Pepin of Landen, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, and his wife Itta of Metz. She is also the grandmother of Charles Martel, who is the grandfather of Charlem ...

and Arnulf's son Ansegisel

Ansegisel (c. 602 or 610 – murdered before 679 or 662) was the younger son of Saint Arnulf, bishop of Metz.

Life

He served King Sigebert III of Austrasia (634–656) as ''domesticus''. He was killed sometime before 679, slain in a feud by his ...

.

As repayment for their help in the Austrasian conquest, Chlotar rewarded both men with important positions of power in Austrasia. However, Arnulf was the first to gain. He was bestowed the bishopric of Metz in 614, entrusting him with the management of the Austrasian capital and the education of Chlotar's young son, the future Dagobert I. This is a position he would hold until his retirement in 629 after Chlotar's death, when he left for a small ecclesiastical community near Habendum; he was later buried at the monastery of Remiremont

Remiremont (; german: Romberg or ) is a town and commune in the Vosges department, northeastern France, situated in southern Grand Est. The town has been an abbatial centre since the 7th century, is an economic crossroads of the Moselle and Mosel ...

after his death c. 645.

Pippin I (624–640)

Pippin was not immediately rewarded, but eventually was given the position of ''maior palatti'' or ' mayor of the palace' of Austrasia in 624. This reward was incredibly important, as it secured Pippin a position of prime importance with the Merovingian royal court. The mayor of the palace would essentially act as the mediator between the King and the magnates of the region; as Paul Fouracre summarises, they were 'regarded as the most important non-royal person in the kingdom.' The reason why Pippin was not rewarded sooner is not certain, but two mayors, Rado (613 – c. 617) and Chucus (c. 617 – c. 624), are believed to have preceded him and were potentially political rivals connected to the fellow Austrasian 'Gundoinings' noble family. Once elected, Pippin served faithfully under Chlotar until the latter's death in 629, and solidified the Pippinids' position of power within Austrasia by supporting Chlotar's son Dagobert, who became King of Austrasia in 623. Pippin, with support from Arnulf and other Austrasian magnates, even used the opportunity to support the killing of an important political rival Chrodoald, an Agilolfing lord. Following King Dagobert I's ascent to the throne in c. 629, he returned Frankish politics back to Paris in Neustria, from whence it had been removed by Chlotar in 613. As a result, Pippin lost his position as mayor and the support of the Austrasian magnates, who were seemingly irritated by his inability to persuade the King to return the political centre to Austrasia. Instead, Dagobert turned to the Pippinids' political rival family, the Gundoinings, whose connections in Adalgesil, Cunibert, archbishop of Cologne, Otto and Radulf (who would later revolt in 642) once again removed the Pippinid and Arnulfing influence in the Austrasia assemblies. Pippin did not reappear in the historical record until Dagobert's death in 638, when he had seemingly been reinstated as mayor of Austrasia and began to support the new young King Sigebert III. According to the ''Continuations'', Pippin made arrangements with his rival, ArchbishopCunibert

Cunibert, Cunipert, or Kunibert (c. 60012 November c. 663) was the ninth bishop of Cologne, from 627 to his death. Contemporary sources mention him between 627 and 643.

Life

Cunibert was born somewhere along the Moselle to a family of the loca ...

, to get Austrasian support for the 10-year-old King Sigibert III, who ruled Austrasia whilst his brother Clovis II ruled over Neustria and Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

. Soon after securing his position once again, he unexpectedly died in 640.

Grimoald (640–656)

Following Pippin's sudden death, the Pippinid family worked swiftly to secure their position. Pippin's daughter Gertrude and wifeItta

Itta of Metz, O.S.B. (also ''Ida'', ''Itte'' or ''Iduberga''; 592–8 May 652) was the wife of Pepin of Landen, Mayor of the Palace of the Kingdom of Austrasia. After his death, she founded the Abbey of Nivelles, where she became a Colombanian ...

founded and entered the Nivelles Abbey, and his only son Grimoald worked to secure his father's position of ''maior palatii.'' The position was not hereditary and therefore passed to another Austrasian noble, Otto, the tutor of Sigebert III. According to the ''Continuations'', Grimoald began to work with his father's accomplice Cunibert to remove Otto from office. He finally succeeded in c. 641, when Leuthar, Duke of the Alamans killed Otto under Grimoald's and, we must assume, Cunibert's orders. Grimoald then became mayor of Austrasia. His power at this time was extensive, with properties in Utrecht, Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

, Tongeren and Maastricht; he was even called 'ruler of the realm' by Desiderius of Cahors

Saint Didier, also known as Desiderius ( AD – November 15, traditionally 655), was a Merovingian-era royal official of aristocratic Gallo-Roman extraction.

He succeeded his own brother, Rusticus of Cahors, as bishop of Cahors and governed the ...

in 643.

This could not have been done if Grimoald had not secured Sigibert III's support. The Pippinids already gained royal patronage from Pippin I's support, but this was further bolstered by Grimoald's role in Duke Radulf of Thuringia's rebellion. Just prior to Otto's assassination, in c. 640 Radulf revolted against the Merovingians and made himself King of Thuringia. Sigibert, with an Austrasian army including Grimoald and Duke Adalgisel, went on campaign and after a brief victory against Fara, son of the assassinated Agilofing

The Agilolfings were a noble family that ruled the Duchy of Bavaria on behalf of their Merovingian suzerains from about 550 until 788. A cadet branch of the Agilolfings also ruled the Kingdom of the Lombards intermittently from 616 to 712.

They ...

lord Chrodoald, the Austrasians met Radulf on the River Unstrut

The Unstrut () is a river in Germany and a left tributary of the Saale.

The Unstrut originates in northern Thuringia near Dingelstädt (west of Kefferhausen in the Eichsfeld area) and its catchment area is the whole of the Thuringian Basin. I ...

where he had set up a stronghold. What followed was a disorganized battle spread over several days, in which the Austrasian lords disagreed on tactics. Grimoald and Adalgesil strengthened their position by defending Sigibert's interests, but could not establish an unanimous agreement. During their final assault, the 'men of Mainz' betrayed the Austrasians and joined with Radulf. This penultimate battle killed many important Austrasian lords, including Duke Bobo

Bobo may refer to:

Animals and plants

* Bobo (gorilla) a popular gorilla at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle from 1953 to 1968

* Bobo, Vietnamese name for Job's tears, a plant of south-east Asia

Entertainment, arts and media

* ''Bobo'' (maga ...

and Count Innowales, and resulted in Sigibert's defeat. The ''Continuations'' offers a famous description of Sigibert being 'seized with the wildest grief and sat there on his horse weeping unrestrainedly for those he had lost' as Radulf returned to his camp victorious.

Upon Sigibert's return from Unstruct, Grimoald, now mayor, began to build power for the Pippinid clan. He utilized the existing links between the family and ecclesiastical community to gain control over local holy men and women who, in turn, supported Pippinid assertions of power. Grimoald established links with Aquitanian and Columbianan missionaries Amandus and Remaclus

Saint Remaclus (Remaculus, Remacle, Rimagilus; died 673) was a Benedictine missionary bishop.

Life

Remaclus grew up at the Aquitanian ducal court and studied under Sulpitius the Pious, bishop of Bourges. In 625 he became a monk at Luxeuil Abbe ...

, both of whom came to be influential bishops within the Merovingian court. Remaclus, in particular, was important as after becoming bishop of Maastricht, he established two monasteries: Stavelot Abbey and Malmedy. Under Grimoald's direction, the Arnulfings were also further established with Chlodulf of Metz

Saint Chlodulf (Clodulphe or Clodould) (605 – June 8, 696 or 697, others say May 8, 697) was bishop of Metz approximately from 657 to 697.

Life

Chlodulf was the son of Arnulf, bishop of Metz, and the brother of Ansegisel, mayor of the pa ...

, son of St. Arnulf, taking the bishopric of Metz in 656.

Grimoald and Childebert (656–657)

The final moment of Grimoald's life is an area that is disputed in both date and event, titled: 'Grimoald's coup'. It involves Grimoald and his son Childebert the Adopted taking the Austrasian throne from the true Merovingian King Dagobert II, son of the late Sigibert who died young at 26 years old. Historians like Pierre Riché are certain that Sigibert died in 656, having adopted Childebert due to his lack of an adult male heir. Following this, young Dagobert II was then exiled and tonsured by Grimoald andDido of Poitiers

Dido ( ; , ), also known as Elissa ( , ), was the legendary founder and first queen of the Phoenician city-state of Carthage (located in modern Tunisia), in 814 BC.

In most accounts, she was the queen of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre (t ...

, who then installed Childebert as King of Austrasia. Clovis II in Neustria, uncle to Dagobert, then reacted to the revolt and lured Grimoald and Childebert into Neustria, where they were executed.

This story is only confirmed by the pro-Neustrian source, the '' Liber Historia Francorum'' (''LHF'') and selected charter evidence. Other contemporary sources like the ''Continuations'' fail to mention the event and Carolingian sources like ''Annales Mettenses Priores'' (''AMP'') ignore the event and even deny Grimoald's existence. As such, historian Richard Gerberding Richard A. Gerberding is professor emeritus and former director of classical studies at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. He taught Latin and Ancient History courses at Willamette University between Fall 2013 and Spring 2015.

Gerberding's e ...

has suggested a different chronology and reading of the ''LHF'', which places Sigibert's death on 1 February 651. According to a Gerberding narrative, Grimoald and Dido organised Dagobert's exile around 16 January 651 to Ireland at Nivelles and then, when Sigibert died a month later, they acted out the plan and tonsured Dagobert, replacing him with Childebert, who ruled until 657. Clovis II then immediately acted and invaded Austrasia, executing Grimoald and his son.

Then, either in 657 or 662, the Neustrians (either Clovis II who died in 657 or his son Chlothar III) installed infant King Childeric II to the throne of Austrasia, marrying him to Bilichild

Bilichild (also Bilichildis, Bilichilde, or Blithilde) was the wife of the Frankish king of Neustria and Burgundy Childeric II. The two were married in 668 despite the opposition of the Bishop Leodegar.

Family

Bilichild was a daughter of King ...

, the daughter of Sigibert's widow Chimnechild of Burgundy

Chimnechild of Burgundy (7th-century – fl. 662) was a Frankish queen consort by marriage to king Sigebert III.

She was the mother of Bilichild and possibly of Dagobert II. When Childebert the Adopted died, she opposed the succession of Theuderi ...

. Grimoald and Childebert's deaths brought an end to the direct Pippinid line of the family, leaving the Arnulfing descendants from Begga and Ansegisel to continue the faction.

Pippin II (676–714)

Very little is known about Pippin's early life, but a controversial story from ''AMP'' suggests that Pippin reclaimed power in Austrasia by killing a legendary 'Gundoin Gundoin was the first Duke of Alsace in the middle of the seventh century. He was a Frankish nobleman from the Meuse-Moselle basin. He was, according to the author of the '' Vita Sadalbergae'', an "illustrious man (''vir inluster''), opulent in weal ...

' as revenge for the assassination of his father Ansegisel. This story is regarded as slightly fantastical by Paul Fouracre, who argues the ''AMP,'' a pro-Carolingian source potentially written by Giselle (Charlemagne's sister) in 805 at Chelles, is that Pippin's role primes him perfectly for his future and demonstrates his family to be 'natural leaders of Austrasia.' However, Fouracre does also acknowledge his existence in charter evidence and confirms that he was a political link to rival mayor Wulfoald

Wulfoald (died 680) was the mayor of the palace of Austrasia from 656 or 661, depending on when Grimoald I was removed from that office (accounts vary: ''see his article for details''), to his death and mayor of the palace of Neustria and Burgundy ...

. These rivalries would make Pippin natural enemies with Gundoin, making the murder plausible as part of Pippin's rise to power.

= Rise to power

= The Arnulfing clan reappear in the contemporary historical record in c. 676, when the ''LHF'' mentions ' Pippin and Martin' rising up against a tyrannicalEbroin

Ebroin (died 680 or 681) was the Frankish mayor of the palace of Neustria on two occasions; firstly from 658 to his deposition in 673 and secondly from 675 to his death in 680 or 681. In a violent and despotic career, he strove to impose the aut ...

, mayor of Austrasia. Pippin II, now head of the faction, and Martin, who was either Pippin's brother or relative, rose up against Ebroin and gathered an army (potentially with the aid of Dagobert II who had been brought back to Austrasia by mayor Wulfoald). According to the ''LHF'', the Arnulfing army met Ebroin, who had gained the support of King Theuderic III, at Bois-du-Fays, and they were easily defeated. Martin fled to Laon, from where he was lured and murdered by Ebroin at Asfeld. Pippin fled to Austrasia and soon received Ermenfred, an officer of a royal fisc who had assassinated Ebroin.

The Neustrians, with Ebroin dead, installed Waratto

Waratto (died 686) was the mayor of the palace of Neustria and Burgundy on two occasions, owing to the deposition he experienced at the hands of his own faithless son. His first term lasted from 680 or 681 (the death of Ebroin) to 682, when his ...

as mayor, and he looked for peace with the Austrasians. Despite an exchange of hostages, Warrato's son Gistemar attacked Pippin at Namur

Namur (; ; nl, Namen ; wa, Nameur) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is both the capital of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Namu ...

and displaced his father. He died shortly thereafter and Warrato resumed his position, wherein peace was reached but tense relations remained until Warrato's death in 686. He left behind his wife Ansfled and his son Berchar

Berchar (also Berthar) was the mayor of the palace of Neustria and Kingdom of Burgundy, Burgundy from 686 to 688/689. He was the successor of Waratton, whose daughter Anstrude he had married.

Unlike Waratton, however, Berthar did not keep peace w ...

, whom the Neustrians installed as mayor. Against his father's policy, Berchar did not maintain peace and incited Pippin into violence.

In 687, Pippin rallied an Austrasian army and led an assault on Neustria, facing Theuderic III and the Neustrian mayor, now Berchar, in combat. They met at the Battle of Tertry

The Battle of Tertry was an important engagement in Merovingian Gaul between the forces of Austrasia under Pepin II on one side and those of Neustria and Burgundy on the other. It took place in 687 at Tertry, Somme, and the battle is presented as ...

, where the ''AMP'' records that Pippin, after offering peace which was rejected by Theuderic at Berchar's behest, crossed the river Omignon at the break of dawn and attacked the Neustrians, who believed the battle won when they saw Pippin's camp abandoned. This surprise attack was successful and the Neustrians fled. Following this victory, Berchar was either killed, as the ''AMP'' argues, by his own people, but the ''LHF'' suggests that it is more likely that he was murdered by his mother-in-law, Ansfled. This moment was decisive in Arnulfing history as it was the first time that any of the faction had national control. Paul Fouracre even argues it is for this that the ''AMP'' starts with Pippin II, as a false dawn upon which Charles Martel would rebuild. However, historians have discredited the importance of this victory. Marios Costambey

Marios is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Marios Agathokleous (born 1974), retired Cypriot football striker

* Marios Batis (born 1980), Greek professional basketball player

* Marios Chakkas (Greek: Μάριος Χάκκας; ...

s, Matthew Innes

Matthew Innes is a British academic who is Vice Master and Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public resear ...

and Simon MacLean

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genu ...

all show that the Tertry victory did not establish solid authority over Neustria immediately, evidenced by the fact that Pippin immediately installed 'Norbert, one of his followers' (as written in the ''LHF'') and then his son Grimoald in 696 to ensure continued influence.

= Consolidation of power

= Pippin II then became overall mayor of the royal palace under Theuderic II, becoming mayor of Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy. His son Drogo, from his wife Plectrude, was also imbued with power when he married Berchar's widow Adaltrude (potentially maneuvered by Ansfled) and was made Duke of Champagne. Pippin was politically dominating and had the power to elect the next two Merovingian kings after Theuderic II died in 691; he installed King Clovis IV (691-695),Childebert III

Childebert III (or IV), called the Just (french: le Juste) (c.678/679 – 23 April 711), was the son of Theuderic III and Clotilda (or Doda) and sole king of the Franks (694–711). He was seemingly but a puppet of the mayor of the palace, P ...

(695-711) and Dagobert III (711-715). Pippin moved to secure further power by consolidating his position in Neustria, installing several bishops like Gripho, Bishop of Rouen and Bainus

Saint Bain (or Bainus, Bagne, Bagnus; died ), a disciple of Saint Vandrille, was a bishop of Thérouanne in northwest France, and then abbot of the monastery of Saint Wandrille in Normandy. His feast day is 20 June.

Monks of Ramsgate account

Th ...

at the Abbey of Saint Wandrille in 701, which was later owned along with Fleury Abbey

Fleury Abbey (Floriacum) in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, Loiret, France, founded in about 640, is one of the most celebrated Benedictine monasteries of Western Europe, and possesses the relics of St. Benedict of Nursia. Its site on the banks of the Lo ...

(founded by Pippin in 703). Imbued with internal strength, Pippin also began to look outwards from the Frankish Empire to subdue the people, that the ''AMP'' records, who once were 'subjected to the Franks ... uch as

Uch ( pa, ;

ur, ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf ( pa, ;

ur, ; ''"Noble Uch"''), is a historic city in the southern part of Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexand ...

the Saxons, Frisians, Alemans, Bavarians, Aquitainians, Gascons and Britons.' Pippin defeated the pagan chieftain Radbod in Frisia, an area that had been slowly encroached upon by Austrasian nobles and Anglo-Saxon missionaries like Willibrord, whose links would later make him a connection between the Arnulfings and the papacy. Following Gotfrid, Duke of Alemannia in 709, Pippin also moved against the Alemans and subjugated them again to royal control.

= Later years

= As Pippin approached his death in late 714, he was faced with a succession crisis. Drogo, Pippin's old son, died in 707 and his second son Grimoald, according to the ''LHF'', was killed whilst praying toSaint Lambert

Lambert of Maastricht, commonly referred to as Saint Lambert ( la, Lambertus; Middle Dutch: ''Sint-Lambrecht''; li, Lambaer, Baer, Bert(us); 636 – c. 705 AD) was the bishop of Maastricht-Liège ( Tongeren) from about 670 until his death. L ...

in Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

in 714 by Rantgar, suspected by Paul Fouracre to be a pagan. Pippin, before his death, made his six year old grandson Theudoald (Grimoald's son) his successor in Neustria, a choice that is believed to have been promoted by his wife Plectrude, which was clearly a political choice from within the direct family line, as Pippin had two adult illegitimate children, Charles Martel and Childebrand I, from a second wife or concubine named Alpaida. They were ousted so Theudoald (with Plectrude's regency) could take the throne, a choice that would result in disaster.

= Death

= When Pippin II died in December 714, the Arnulfings' dominance over Francia disintegrated. The ''LHF'' tells us that 'Plectrude along with her grandchildren and the king directed all the affairs of state under a separate government', a system which created tensions with the Neustrians. Theudoald ruled uncontested for around six months, until June 715, when the Neustrians revolted. Theudoald and the Arnulfings' supporters met at theBattle of Compiègne

The Battle of Compiègne was fought on 26 September 715 and was the first definite battle of the civil war which followed the death of Pepin of Heristal, Duke of the Franks, on 16 December 714.

Dagobert III had appointed one Ragenfrid as may ...

on 26 September 715, and after a decisive victory, the Neustrians installed a new mayor Ragenfrid and, following Dagobert's death, their own Merovingian king Chilperic II. Charter evidence suggests that Chilperic was the son of the former King Childeric II, but this would make Daniel in his 40s, which is quite old to take the throne.

Charles Martel (714–741)

= Rise to power

= Following their victory, the Neustrians joined withRadbod, King of the Frisians

Redbad or Radbod (died 719) was the king (or duke) of Frisia from c. 680 until his death. He is often considered the last independent ruler of Frisia before Frankish domination. He defeated Charles Martel at Cologne. Eventually, Charles prevaile ...

and invaded Austrasia, aiming towards the Meuse river to take the heartland of the faction's support. It is at this moment that Charles Martel is first mentioned in historical records, which note him surviving imprisonment by his step-mother, Plectrude. Charles managed to escape and mustered an Austrasian army to face the encroaching Radbod and the Neustrians. In 716, Charles finally met the Frisians as they approached and, although the ''AMP'' attempts equalize the losses, it is confirmed from the descriptions in the ''LHF'' and the ''Continuations'' that Charles was defeated with heavy losses. Chilperic, Raganfred and, according to the ''Continuations'', Radbod, then travelled from Neustria through the forest of the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

and raided around the river Rhine and Cologne, taking treasure from Plectrude and her supporters. As they returned, Charles ambushed the returning party at the Battle of Amblève and was victorious, inflicting heavy losses on the Neustrian invaders.

In 717, Charles mustered his army again and marched on Neustria, taking the city of Verdun during his conquest. He met Chilperic and Raganfred again at the Battle of Vinchy

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 21 March 717 and was once again victorious, forcing them back to Paris. He then swiftly returned to Austrasia and besieged Cologne, defeating Plectrude and reclaiming his father's wealth and treasure. Charles bolstered his position by installing the Merovingian king Chlothar IV in Austrasia as an opposing Merovingian to Chilperic II. Despite not having a Merovingian king for around 40 years in Austrasia, Charles' position was clearly weak at this time and he required the support of the established Merovingians to gather military support. Despite his weaknesses, Charles' recent success had made him a greater political entity; as such, Chilperic and Raganfred could not win a decisive victory against him. So, in 718 they too sent embassies and won the support of Duke Eudo of Aquitaine who, at their request, mustered 'a Gascon army' to face Charles. In response, Charles brought an army to the eastern Neustrian borders and faced Duke Eudo in battle at Soissons. Duke Eudo, realising he was outmatched, retreated to Paris, where he took Chilperic and the royal treasury and left for Aquitaine. Charles pursued them, according to the ''Continuations'', as far as Orleans, but Eudo and the Neustrians managed to escape. In 718, King Chlothar IV died and was not replaced; instead, Charles became the primary authority in Francia. He established a peace treaty with Duke Eudo that ensured Chilperic II was returned to Francia; thereafter, until Chilperic's death in 720 at Noyon, the kingship was restored with Carolingian control and Charles became the ''maior palatii'' in both Neustria and Austrasia. Following Chilperic II's death, the Merovingian king Theuderic IV, son of Dagobert III, was taken from Chelles Abbey and appointed by the Neustrians and Charles as the Frankish king.

= Consolidation of power

= With his ascension to the throne, several significant moments in Frankish history occurred. Firstly, the ''LHF'' ended, likely composed several years later in 727 and ended one of the several perspectives we have on Charles' ascension. Secondly, and more importantly, the Arnulfing predominance in the faction ended and the Carolingian (translating to 'sons of Charles') officially began. Once the immediate dangers were dealt with, Charles then began to consolidate his position as sole mayor of the Frankish kingdom. The civil unrest between 714 and 721 had destroyed the continental political cohesion, and peripheral kingdoms like Aquitaine, Alemannia, Burgundy and Bavaria had slipped from the Carolingian's grasp. Even though the faction had, by Charles Martel's time, established strong political control over Francia, loyalty to the Merovingian power within these border regions remained.Ending the Civil War Charles first set out to reinstate Carolingian dominance internally within Francia: the ''Continuations'' lists Charles' continuous maneuvers which solidified the campaigns generating the Carolingian military foundation. In 718, the ''AMP'' records that Charles fought against the Saxons, pushing them as far as the river Weser and following up with subsequent campaigns in 720 and 724 which secured the northern borders of Austrasia and Neustria. He subdued his former enemy Raganfred at Angers in 724 and secured his patronage, removing the remaining political resistance that had continued to thrive in western Neustria.

East of the Rhine In 725, Charles set out against the peripheral kingdoms, starting with Alemannia. The region had almost gained independence during the reign of Pippin II and under the leadership of Lantfrid, Duke of Alemannia, as (710–730) they acted without Frankish authority, issuing law codes like the ''

Lex Alamannorum The Lex Alamannorum and Pactus Alamannorum were two early medieval law codes of the Alamanni. They were first edited in parts in 1530 by Johannes Sichard in Basel.

Pactus Alamannorum

The ''Pactus Alamannorum'' or ''Pactus legis Alamannorum'' is the ...

'' without Carolingian consultation. As recorded in the Alemannia source, the ''Breviary of Erchanbert

A breviary (Latin: ''breviarium'') is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such ...

'', the Alemanni 'refused to obey the duces of the Franks because they were no longer able to serve the Merovingian kings. Therefore, each of them kept to himself.' This statement was true for more than just Alemannia and, just like in those regions, Charles brutally forced them into submission. Charles was successful in his first campaign, but returned in 730, the same year that Duke Lantfrid died and was succeeded by his brother Theudebald, Duke of Alamannia.

As successful as campaigning had been, Charles seemingly took inspiration from Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

missionary Saint Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictines, Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant ...

, who in 719 was sent by Pope Gregory II to convert Germany, in particular the areas of Thuringia and Hesse, where he established the monasteries of Ohrdruf, Tauberbischofsheim, Kitzingen

Kitzingen () is a town in the Germany, German state of Bavaria, capital of the Kitzingen (district), district Kitzingen. It is part of the Franconia geographical region and has around 21,000 inhabitants. Surrounded by vineyards, Kitzingen County i ...

and Ochsenfurt

Ochsenfurt () is a town in the district of Würzburg, in Bavaria, Germany. Ochsenfurt is located on the left bank of the River Main and has around 11,000 inhabitants. This makes it the largest town in Würzburg district.

Name

Like Oxford, the t ...

. Charles, realising the potential of establishing Carolingian-supportive episcopal centres, utilised Saint Pirmin

Saint Pirmin (latinized ''Pirminius'', born before 700 ( according to many sources), died November 3, 753 in Hornbach), was a Merovingian-era monk and missionary.

He founded or restored numerous monasteries in Alemannia (Swabia), especially in ...

, an itinerant monk, to establish an ecclesiastical foundation on Reichenau Island

Reichenau Island () is an island in Lake Constance in Southern Germany. It lies almost due west of the city of Konstanz, between the Gnadensee and the Untersee, two parts of Lake Constance. With a total land surface of and a circumference of ...

in Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

. He was expelled in 727 by Lantfrid and he retreated to Alsace, where he established monasteries with the support of the Etichonid

The Etichonids were an important noble family, probably of Frankish, Burgundian or Visigothic origin, who ruled the Duchy of Alsace in the Early Middle Ages (7th–10th centuries). The dynasty is named for Eticho (also known as Aldarich), who ru ...

clan, who were Carolingian supporters. This relationship gave the Carolingians long-term benefit from Pirmin's future achievements, which brought abbeys in the eastern provinces into Carolingian favour.

In 725, Charles continued his conquest from Alemannia and invaded Bavaria. Like Alemannia, Bavaria had continued to gain independence under the rule of the Agilolfings clan who, in recent years, had increased links with Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

and affirmed their own law codes, like the Lex Baiuvariorum. When Charles moved, the region was experiencing a power struggle between Grimoald of Bavaria and his nephew Hugbert, but when Grimoald died in 725, Hugbert gained the position and Charles reaffirmed their support. The ''Continuations'' records that when Charles left Bavaria, he took hostages, one of which was Swanachild

Swanachild (also ''Swanahild'' or ''Serenahilt'') was the second wife of Charles Martel.

Reign

Swanachild belonged to the clan of the Agilolfing, though her parentage is not quite clear. Her parents could be Tassilo II, duke of Bavaria, and his w ...

, who later would become Charles' second wife. Paul Fouracre believes this marriage could have been intentionally forced, based upon the fact that Swanchild's heritage related her both to Alemannia and Bavaria. Not only would their marriage have allowed greater control over both regions, but it also would have cut the existing family ties that the Agilofings had to the Pippinid family branch. Plectrude's sister Regintrud was married to Theodo of Bavaria, and this relation provided an opportunity for disenfranchised family members to defect.

Aquitaine, Burgundy and Provence Following his conquest east of the Rhine, Charles had the opportunity to assert his dominance over Aquitaine and began committing military resources and performing raids in 731. However, before he could make any major movements, Aquitaine was invaded by Umayyad warlord Abd al-Rahman I. Following Abd al-Rahman's ascension in Spain in 731, another local Berber lord Munuza revolted, set himself up at

Cerdanya

Cerdanya () or often La Cerdanya ( la, Ceretani or ''Ceritania''; french: Cerdagne; es, Cerdaña), is a natural comarca and historical region of the eastern Pyrenees divided between France and Spain. Historically it was one of the counties ...

and forged defensive alliances with the Franks and Aquitainians through a marriage to Eudo's daughter. Abd ar-Rahman then besieged Cerdanya and forced Munuza into retreat into France, at which point he continued his advance into Aquitaine, moving as far as Tours before he was met by Charles Martel. Carolingian sources attest that Duke Eudo begged Charles for assistance, but Ian N. Wood

Ian N. Wood, (born 1950) is an English scholar of early medieval history, and a professor at the University of Leeds who specializes in the history of the Merovingian dynasty and the missionary efforts on the European continent. Patrick J. Gear ...

claims these embassies have been invented by later pro-Carolingian annalists. Eudo was a main protagonist in the Battle of Toulouse (721), which famously stopped Muslim lord Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani's advances in Narbonne and gained Eudo praise in the ''Liber Pontificalis

The ''Liber Pontificalis'' (Latin for 'pontifical book' or ''Book of the Popes'') is a book of biographies of popes from Saint Peter until the 15th century. The original publication of the ''Liber Pontificalis'' stopped with Pope Adrian II (867� ...

''.

Charles met the Muslim force at the famous Battle of Poitiers (732)

The Battle of Tours, also called the Battle of Poitiers and, by Arab sources, the Battle of tiles of Martyrs ( ar, معركة بلاط الشهداء, Maʿrakat Balāṭ ash-Shuhadā'), was fought on 10 October 732, and was an important battle ...

and came out victorious, killing Abd ar-Rahman. This moment cemented Charles Martel in historical records and gained him international praise. Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

, writing at the same time in Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the Tyne ...

, England, recorded the event in his ''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum'', and his victory gained Charles Martel the admiration of seminal historian Edward Gibbon who considered him the Christian saviour of Europe. Although his victory was considered famous, in reality his victory was far less impactful, and Charles would not gain much control in Aquitaine until Eudo's death in 735. The victory may have given the Carolingians relative local support that potentially allowed Charles to assert dominance over Eudo's son and successor Hunald of Aquitaine Hunald, also spelled Hunold, Hunoald, Hunuald or Chunoald (french: Hunaud; la, Hunaldus or ''Chunoaldus''), is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It may refer to:

*Hunald I, duke of Aquitaine (735–45)

*Hunald II, duke of Aquitaine (768� ...

, but records of continued hostilies in 736 only further cemented that relations were strained.

With a stronger establishment in Aquitaine, Charles made moves to assert his dominance into Burgundy. The region, at least in the Northern areas, had remained controlled and allied with Frankish interest. Influential nobility like Savaric of Auxerre Savaric (died 715) was the Bishop of Auxerre from 710 until his death. A member of high nobility, he was a warrior who held a bishopric. He was the father of Eucherius, Bishop of Orleans.

He gathered a large army and subjected the region of the N ...

, who had maintained near-autonomy and led military forces against Burgundian towns like Orléans, Nevers and Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near to ...

, even dying whilst besieging Lyon, were the key to Charles' support. As such, Charles made multiple attempts to both gain the faction's support and remove their authority. When Savaric died during Charles' early reign, he agreed to support Savaric's nephew Bishop Eucherius of Orléans' claim to the bishopric. However, once Charles had established a powerful basis by 737, he exiled Eucherius, with the help of a man called Chrodobert, to the monastery of St Trond

Saint Trudo (Tron, Trond, Trudon, Trutjen, Truyen) (died ca. 698) was a saint of the seventh century. He is called the "Apostle of Hesbaye" (partly in the provinces of Brabant and Limburg, Belgium). His feast day is celebrated on 23 November.

...

. Charles took further military action in the same year to fully assert his authority, and installed his sons Pippin and Remigius as magnates. This was followed by the installation of political supporters from Bavaria and local supporters like Theuderic of Autun

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

and Adalhard of Chalon Adelard (also spelled Adelhard, Adalhard or Adalard) may refer to:

People in the Middle Ages

*Adelard, father of the Frankish saint Herlindis of Maaseik (died 745)

*Adalard of Corbie (751–827), Frankish abbot

*Adelard of Spoleto (died 824), Ital ...

.

This acquisition of land in southern France was supported by the increased social chaos that seemingly developed during the Civil War years. This was most apparent in Provence, where local magnates, like Abbo of Provence, were incredibly supportive of Charles' attempts to reinstate Frankish power. In 739, he used his power in Burgundy and Aquitaine to lead an attack with his brother Childebrand I against Arab invaders and Duke Maurontus, who had been claiming independence and allying himself with Muslim emir Abd ar-Rahman. It is likely due to Childebrand's sponsorship of the manuscript that his involvement is so extensively recorded in the ''Continuations''. According to the manuscript, Childebrand and Charles noticed the Arab army, with Maurontus' welcome, entering Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

and quickly moved against the alliance. They besieged the city and claimed victory; the Franks then made the decision to invade Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

, taking Narbonne and flanking the Arab army. The Franks then fought off a support army sent from Spain under Omar-ibn Chaled at the River Berre. From there the Franks then pursued the retreating Arabs and ravaged the cities of Nîmes

Nîmes ( , ; oc, Nimes ; Latin: ''Nemausus'') is the prefecture of the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. Located between the Mediterranean Sea and Cévennes, the commune of Nîmes has an estimated population of 148,5 ...

, Agde

Agde (; ) is a commune in the Hérault department in Southern France. It is the Mediterranean port of the Canal du Midi.

Location

Agde is located on the Hérault river, from the Mediterranean Sea, and from Paris. The Canal du Midi con ...

and Béziers

Béziers (; oc, Besièrs) is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Hérault Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region of Southern France. Every August Béziers hos ...

before returning to Francia. Later that year, Charles and Childebrand returned to Provence, likely collecting more forces, and then forcing the rebellious Maurontus into 'impenetrable rocky fastnesses out to sea.' Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, s ...

later records in his '' Historia Langobardorum'' Maurontus received help from the Lombards, and his Arab allies then fled. At this time, Charles then assumed control of the region and, judging from Charter evidence, appointed Abbo of Provence as ''patricius'' (Patrician) in the region.

= Ruling Francia

= Charles also ruled the Frankish realm, although the majority of his policies were centred upon his conquests and his military ventures. In 19th century historiography, historians likeHeinrich Brunner

Heinrich Brunner ( en, Henry Brunner; 21 June 1840 – 11 August 1915) was a German historian.

Life

Brunner was born at Wels in Upper Austria. After studying at the universities of Vienna, Göttingen and Berlin, he became professor at the Un ...

even centred their arguments around Charles' necessity for military resources, in particular the development of mounted warrior or cavalry that would peak in the High Middle Ages. However, in modern historiography, historians like Pierre Riche and Paul Fouracre have discredited his ideas as too simplistic and have aimed to depict more realistic fragments of development that may or not have been interdependent. This was the period in which the Carolingians first began to establish themselves as fully independent from the Merovingian royalty.

Vassalage and Church Charles Martel has become notorious in historiography for his role in the development of the concept of feudalism. The debates are rooted in the arguments of historians like

François-Louis Ganshof François-Louis or François Louis may refer to:

*François Louis, Prince of Conti (1664–1709), French nobleman

*François Louis, Count of Harcourt (1623–1694) French nobleman

*François Louis, inventor of the aulochrome, a musical instrument

...

, who viewed Charles' reign as the birth of the 'feudal' relationship between power and property. This results from the increased use of ''precaria

The precarium (plural precaria)—or precaria (plural precariae) in the feminine form—is a form of land tenure in which a petitioner (grantee) receives a property for a specific amount of time without any change of ownership. The precarium is t ...

'' or temporary land grants by the Carolingians, who allocated and spread their power to their subordinates. Ganshof's arguments connect these ties to a military-tenure relationship; however, this is never represented in primary material, and instead is only implied, and likely derived from, an understanding of 'feudalism' in the High Middle Ages. Recent historians like Paul Fouracre have criticised Ganshof's review for being too simplistic, and in reality, even though these systems of vassalage did exist between lord and populace, they were not as standardised as older historiography has suggested. For example, Fouracre has drawn particular attention to the incentives that drew lords and warriors into the Carolingian armies, arguing that the primary draw was 'booty' and treasure gained from conquest rather than 'feudal' obligation.

Although Charles' reign is no longer considered transitional in its feudal developments, it is seen as a transitional period in the spread of the existing system of vassals and ''precaria'' land rights. Due to Charles' continued military and missionary work, the political systems that existed in the heartlands, Austrasia and Neustria, officially began to spread to the periphery. Those whom Charles appointed as new nobility in these regions, often with lifetime tenures, ensured that Carolingian loyalties and systems was maintained across the kingdoms. The Carolingians were also far more strict with their land rights and tenure than their Merovingian predecessors, carefully distributing their new land to new families temporarily, but maintaining their control. Merovingians kings weakened themselves by allocating too much of their royal domains to supporting factions; the Carolingians themselves seemingly became increasingly powerful due to their generosity. By giving away their land, the Merovingians allowed themselves to become figureheads and the 'do nothing kings' that Einhard prefaced in the ''Vita Karoli Magni''.

Due to his vast military conquests, Charles often reallocated existing land settlements, including Church property, to new tenants. Ecclesiastical property and monasteries in the late Merovingian and Carolingian period were political centres and often closely related to the royal court; as such they often became involved in political matters, which often overlapped with Charles' reallocation of land. This 'secularisation' of Church property caused serious tension between the Carolingian church and state, and often gave Charles a negative depiction in ecclastical sources. The reallocation of church land was not new by Charles' reign; Ian Wood has managed to identify the practice going back to the reigns of Dagobert I (629–639) and Clovis II (639–657). The majority of the sources that depict Charles' involvement in Church land rights come from the 9th century, and are therefore less reliable, but two supposedly contemporary sources also identify this issue. The first, a letter sent by missionary Saint Boniface to Anglo-Saxon king Æthelbald of Mercia, called Charles' a 'destroyer of many monasteries, and embezzler of Church revenues for his own use...', condemning him for his use of Church property. This is supported by the second source, the ''Contintuations'', which related that, in 733 in Burgundy, Charles split the Lyonnais between his followers, this likely including Church land. Further chronicles like the ''Gesta episcoporum Autissiodorensium

Gesta may refer to:

Titles of works

Gesta is the Latin word for "deeds" or "acts", and Latin titles, especially of medieval chronicles, frequently begin with the word, which thus is also a generic term for medieval biographies:

* Gesta Adalberonis ...

'' and the ''Gesta Sanctorum Patrum Fontanellensis Coenobii

The ''Gesta abbatum Fontanellensium'' (Deeds of the Abbots of Fontenelle), also called the ''Gesta sanctorum patrum Fontanellensis coenobii'' (Deeds of the Holy Fathers of the Monastery of Fontenelle), is an anonymous Latin chronicle of the Abbey ...

'' recorded monasteries losing substantial land. The monastery at Auxerre was reduced to a hundred ''mansus A ''mansus'', sometimes anglicised as manse, was a unit of land assessment in medieval France, roughly equivalent of the hide. In the 9th century AD, it began to be used by Charlemagne to determine how many warriors would be provided: one for eve ...

'' by Pippin III's reign, and at the Abbey of Saint Wandrille under Abbot Teutsind

Teutsind () was a Frankish cleric, abbot of St Martin, Tours, and of Fontenelle Abbey.W Davies and P Fouracre (2002): ''Property and Power in the Early Middle Ages'' (Cambridge University Press), pp.42-43Susan Wood, 2006: ''The Proprietary Chu ...

, who was appointed by Charles in 735/6, the Church's local property was reduced to a third its size. Wood has also criticised this point and proven that the loss of land by the Church was in reality very small, the remaining land being simply leased as it went beyond the Church's capabilities. Regardless, it is apparent that Charles' expansion of control consumed plenty of reallocated properties, many of which were ecclesiastical domains.

= Interregnum, Death & Divisions

= When King Theuderic IV died in 737, Charles did not install a Merovingian successor. Unlike his Carolingian predecessors, Charles was clearly strong enough by the end of his reign to not rely on Merovingian loyalties. He had created his own power bloc through the vassals he installed in Frankish heartlands and peripheral states. Even prior to Theuderic's death, Charles did act with complete sovereignty in Austrasia. It was only in areas like Neustria, where Carolingian opposition historically existed, that Charles knew he would face criticism if he usurped the throne. Therefore, until his death, Charles ruled as ''Princeps'' or Prince, officially gaining the title with his uncontested leadership with the acquisition of Provence in 737. This meant that the issue of kingship remained ever present for his successors who would have to work further to establish themselves as royal. When Charles died in 741, he was buried at St Denis in Paris. He made secure succession plans, likely learning from his father, that ensured Francia was effectively divided between his sons, Carloman and Pippin as ''maior palatii''. According to the ''Continuations'', the eldest son, Carloman, was given control of the eastern kingdoms in Austrasia, Alammania and Thuringia, while Pippin was given the western kingdoms in Burgundy, Neustria and Provence.Charlemagne

Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

at Rome in 800. His empire, ostensibly a continuation of the Western Roman Empire, is referred to historiographically as the Carolingian Empire.

The Carolingian rulers did not give up the traditional Frankish (and Merovingian) practice of dividing inheritances among heirs, though the concept of the indivisibility of the Empire was also accepted. The Carolingians had the practice of making their sons minor kings in the various regions (''regna'') of the Empire, which they would inherit on the death of their father, which Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious both did for their sons. Following the death of the Emperor Louis the Pious in 840, his surviving adult sons, Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

and Louis the German, along with their adolescent brother Charles the Bald, fought a three-year civil war ending only with the Treaty of Verdun in 843, which divided the empire into three ''regna'' while according imperial status and a nominal lordship to Lothair who, at 48, was the eldest. The Carolingians differed markedly from the Merovingians in that they disallowed inheritance to illegitimate offspring, possibly in an effort to prevent infighting among heirs and assure a limit to the division of the realm. In the late ninth century, however, the lack of suitable adults among the Carolingians necessitated the rise of Arnulf of Carinthia

Arnulf of Carinthia ( 850 – 8 December 899) was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894 and the disputed emperor from Feb ...

as the king of East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

, a bastard child of a legitimate Carolingian king, Carloman of Bavaria, himself a son of the First King of the Eastern division of the Frankish kingdom, Louis the German.

Decline

It was after Charlemagne's death that the dynasty began to slowly crumble. His kingdom was split into three parts, each being ruled over by one of his grandsons. Only the kingdoms of the eastern and western portions survived, becoming the predecessors of modern Germany and France. The Carolingians were displaced in most of the ''regna'' of the Empire by 888. They ruled inEast Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

until 911 and held the throne of West Francia intermittently until 987. Carolingian cadet branches continued to rule in Vermandois and Lower Lorraine after the last king died in 987, but they never sought the royal or imperial thrones and made peace with the new ruling families. One chronicler of Sens

Sens () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yonne Departments of France, department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in north-central France, 120 km from Paris.

Sens is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture and the second city of the d ...

dates the end of Carolingian rule with the coronation of Robert II of France as junior co-ruler with his father, Hugh Capet, thus beginning the Capetian dynasty

The Capetian dynasty (; french: Capétiens), also known as the House of France, is a dynasty of Frankish origin, and a branch of the Robertians. It is among the largest and oldest royal houses in Europe and the world, and consists of Hugh Cape ...

. The Carolingian dynasty became extinct in the male line with the death of Eudes, Count of Vermandois. His sister Adelaide, the last Carolingian, died in 1122.

Branches

The Carolingian dynasty has five distinct branches:

#The Lombard branch, or Vermandois branch, or Herbertians, descended from

The Carolingian dynasty has five distinct branches:

#The Lombard branch, or Vermandois branch, or Herbertians, descended from Pepin of Italy

Pepin or Pippin (or ''Pepin Carloman'', ''Pepinno'', April 777 – 8 July 810), born Carloman, was the son of Charlemagne and King of the Lombards (781–810) under the authority of his father.

Pepin was the second son of Charlemagne by his th ...

, son of Charlemagne. Though he did not outlive his father, his son Bernard was allowed to retain Italy. Bernard rebelled against his uncle Louis the Pious, and lost both his kingdom and his life. Deprived of the royal title, the members of this branch settled in France, and became counts of Vermandois, Valois, Amiens and Troyes. The counts of Vermandois perpetuated the Carolingian line until the 12th century. The Counts of Chiny and the lords of Mellier, Neufchâteau and Falkenstein are branches of the Herbertians. With the descendants of the counts of Chiny, there would have been Herbertian Carolingians to the early 13th century.

#The Lotharingian branch, descended from Emperor Lothair, eldest son of Louis the Pious. At his death Middle Francia was divided equally between his three surviving sons, into Italy, Lotharingia and Lower Burgundy. The sons of Emperor Lothair did not have sons of their own, so Middle Francia was divided between the western and eastern branches of the family in 875.

#The Aquitainian branch, descended from Pepin of Aquitaine, son of Louis the Pious. Since he did not outlive his father, his sons were deprived of Aquitaine in favor of his younger brother Charles the Bald. Pepin's sons died childless. Extinct 864.

#The German branch, descended from Louis the German, King of East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

, son of Louis the Pious. Since he had three sons, his lands were divided into Duchy of Bavaria, Duchy of Saxony and Duchy of Swabia

The Duchy of Swabia (German: ''Herzogtum Schwaben'') was one of the five stem duchies of the medieval German Kingdom. It arose in the 10th century in the southwestern area that had been settled by Alemanni tribes in Late Antiquity.

While the ...

. His youngest son Charles the Fat briefly reunited both East and West Francia – the entirety of the Carolingian empire – but it split again after his death, never to be reunited again. With the failure of the legitimate lines of the German branch, Arnulf of Carinthia

Arnulf of Carinthia ( 850 – 8 December 899) was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894 and the disputed emperor from Feb ...

, an illegitimate nephew of Charles the Fat, rose to the kingship of East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

. At the death of Arnulf's son Louis the Child

Louis the Child (893 – 20/24 September 911), sometimes called Louis III or Louis IV, was the king of East Francia from 899 until his death and was also recognized as king of Lotharingia after 900. He was the last East Frankish ruler of the Car ...

in 911, Carolingian rule ended in East Francia.

#The French branch, descended from Charles the Bald, King of West Francia, son of Louis the Pious. The French branch ruled in West Francia, but their rule was interrupted by Charles the Fat of the German branch, two Robertians, and a Bosonid

The Bosonids were a dynasty of Carolingian era dukes, counts, bishops and knights descended from Boso the Elder. Eventually they married into the Carolingian dynasty and produced kings and an emperor of the Frankish Empire.

The first great scion o ...

. Carolingian rule ended with the death of Louis V of France in 987. Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, the Carolingian heir, was ousted out of the succession by Hugh Capet; his sons died childless. Extinct c. 1012.

Charles Martel (c. 688 or 686, 680–741), Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, had six sons (3 illegitimate);Annales Einhardi 741, MGH SS I, p. 135

:1. Carloman (between 706 and 716–754), Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace in Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, had one son;

::A. Drogo (b. before 741), Mayor of the Palace in Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

;

:2. Pepin (or Pippin) the Younger (known under the mistranslation Pepin the Short) (c. 714–768), King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

(f. 754), had three sons;

::A. Charlemagne (Charles I the Great) (748–814), King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

(f. 768), King of Italy (f. 774), Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

(f. 800), had nine sons (4 illegitimate);

:::I. Pepin (or Pippin) the Hunchback (770–811), illegitimate son, died without issue;

:::II. Charles the Younger (772/73–811), King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

(f. 800), died without issue;

Herbertians or Lombard branch or Vermandois branch;

:::III. Pepin I (or Pippin) born Carloman (777–810), King of Italy (f. 781), had one illegitimate son;

::::a. Bernard I (797–818), King of Italy (f. 810), had one son;

:::::i. Pepin (815 – ''after'' 850) Count of Vermandois (after 834), Lord of Senlis, Péronne, and Saint Quentin, had three sons;

::::::1. Bernard II (c. 844 – after 893), Count of Laon had one son;

::::::2. Pepin III

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of t ...

(846–893), Count of Senlis and Valois, had one son;

::::::3. Herbert I (850–907), Count of Vermandois (f. 896), Meaux, and Soissons, abbot of Saint Quentin, had one son;

:::::::A. Herbert II (884–943), Count of Vermandois, Meaux and Soissons, and abbot of St. Medard

Saint Medardus or St Medard (French: ''Médard'' or ''Méard'') (ca. 456–545) was the Bishop of Noyon. He moved the seat of the diocese from Vermand to Noviomagus Veromanduorum (modern Noyon) in northern France. Medardus was one of the most ...

, and Soissons, had six sons;

::::::::I. Otto (or Eudes) of Vermandois-Vexin (910–946), Count of Amiens, died without issue;

::::::::II. Herbert III 'the Old' (911–993), Count of Omois, Meaux and Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near to ...

, and abbot of St. Medard

Saint Medardus or St Medard (French: ''Médard'' or ''Méard'') (ca. 456–545) was the Bishop of Noyon. He moved the seat of the diocese from Vermand to Noviomagus Veromanduorum (modern Noyon) in northern France. Medardus was one of the most ...

, Soissons, died without issue

::::::::III. Robert (d. 968), Count of Meaux (f.943) and Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near to ...

(f.956), had one son;

:::::::::a. Herbert II 'the Younger', Count of Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near to ...

, Meaux, and Omois (950–995) had one son;

::::::::::i. Stephen, Count of Troyes, Meaux, Vitry and Omois (d. 1020) died without male issue;

::::::::IV. Adalbert I 'the Pious' (916–988), Count of Vermandois (f. 943) had four sons;

:::::::::a. Herbert IV (953–1015), Count of Vermandois, had three sons;

::::::::::i. Adalbert II (c. 980–1015), Count of Vermandois, died without issue;

::::::::::ii. Landulf, Bishop of Noyon, died without issue;

::::::::::iii. Otto

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''Audo'', ''Odo'', ''Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded fro ...

(979–1045), Count of Vermandois, had three sons;

:::::::::::1. Herbert IV (1028–1080) Count of Vermandois, had one son and one daughter;

::::::::::::A. Odo 'the Insane' (d. ''after'' 1085), Lord of Saint-Simon, died without issue;

::::::::::::B. Adelaide (d. 1122), Countess of Vermandois and Valois (f. 1080);

:::::::::::2. Eudes I (b. 1034), Lord of Ham;

:::::::::::3. Peter of Vermandois;

:::::::::b. Eudes of Vermandois

:::::::::c. Liudolfe (c. 957–986), Bishop of Noyon;

:::::::::d. Guy Count of Soissons

::::::::V. Hugh of Vermandois (920–962) Archbishop of Rheims, died without issue;

:::IV. Louis I the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqui ...

also called the Fair, and the Debonaire (778–840), King of Aquitaine (f. 781), King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

and Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

(f. 814), had five sons (one illegitimate);

Lotharingian branch

::::a. Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

(795–855) Emperor (f.840) had 4 sons;

:::::i. Louis II the Young (825–875), King of Italy (f.844), Emperor (f.850) died without male issue;

:::::ii. Lothair II

Lothair II (835 – 8 August 869) was the king of Lotharingia from 855 until his death. He was the second son of Emperor Lothair I and Ermengarde of Tours. He was married to Teutberga (died 875), daughter of Boso the Elder.

Reign

For political ...

(835–869), King of Lotharingia had one son (illegitimate);

::::::1. Hugh

Hugh may refer to:

*Hugh (given name)

Noblemen and clergy French

* Hugh the Great (died 956), Duke of the Franks

* Hugh Magnus of France (1007–1025), co-King of France under his father, Robert II

* Hugh, Duke of Alsace (died 895), modern-day ...

(855–895), Duke of Alsace

The Duchy of Alsace ( la, Ducatus Alsacensi, ''Ducatum Elisatium''; german: Herzogtum Elsaß) was a large political subdivision of the Frankish Empire during the last century and a half of Merovingian rule. It corresponded to the territory of Alsac ...

, died without issue;

:::::iii. Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

(845–863), Lord of Provence, Lyon and Transjuranian Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

, died without issue

:::::iv. Carloman (853–?)

Aquitainian branch

::::b. Pepin I

Pepin I (also Peppin, Pipin, or Pippin) of Landen (c. 580 – 27 February 640), also called the Elder or the Old, was the Mayor of the palace of Austrasia under the Merovingians, Merovingian King Dagobert I from 623 to 629. He was also the ...

(797–838), King of Aquitaine (f.814) had 2 sons;

:::::i. Pepin (823–864), died without issue;

:::::ii. Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

(825/30–863), Archbishop of Mainz

The Elector of Mainz was one of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. As both the Archbishop of Mainz and the ruling prince of the Electorate of Mainz, the Elector of Mainz held a powerful position during the Middle Ages. The Archb ...

, died without issue;

German branch

::::c. Ludwig (Louis) II the German (806–876), King of the East Franks (f.843), King of East Lotharingia as Louis I, had 3 sons;

:::::i. Carloman (830–880), King of the Bavaria (876–879), King of Italy (877–879), had one son (illegitimate);

::::::1. Arnulf

Arnulf is a masculine German given name.

It is composed of the Germanic elements ''arn'' "eagle" and ''ulf'' "wolf".

The ''-ulf, -olf'' suffix was an extremely frequent element in Germanic onomastics and from an early time was perceived as a mere ...

(850–899), King of East Francia (f.887), disputed King of Italy (f. 894), Emperor (f.896), had 3 sons;

:::::::A. Ludwig IV (Louis) the Child (893–911), King of The East Franks (f. 900), King of Lotharingia as Louis III (f.900), died without issue;

:::::::B. Zwentibold

Zwentibold (''Zventibold'', ''Zwentibald'', ''Swentiboldo'', ''Sventibaldo'', ''Sanderbald''; – 13 August 900), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was the illegitimate son of Emperor Arnulf.Collins 1999, p. 360 In 895, his father granted hi ...

(870/71–900), King of Lotharingia (f.895), died without issue;

:::::::C. Ratold of Italy Ratold was a king of Italy who reigned for a month or so in 896. He was an illegitimate son of King Arnulf of East Francia. He and his half-brother Zwentibold are described by the '' Annals of Fulda'' as being born "by concubines" (''ex concubinis' ...

(889–929) died without issue

:::::ii. Ludwig III (Louis) the Younger (835–882), King of the East Franks, and King of East Lotharingia as Louis II (f.876), King of LotharingiCharles II the Bald