Carl Albert on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carl Bert Albert (May 10, 1908 – February 4, 2000) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 46th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1971 to 1977 and represented

''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. Accessed April 24, 2015. The couple had two children, Mary Frances and David. Albert served in the Judge Advocate General Corps as a prosecutor assigned to the Far East Air Service Command. He earned a

Ex-House Speaker Carl Albert dies, Feb. 4, 2000

Politico.com, February 4, 2011 (accessed April 12, 2014). He remained in the Army Reserve after the war, and retired in 1968 with the rank of

Retrieved May 14, 2014. Albert was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1957.

As Majority Leader, Albert was a key figure in advancing the Democratic legislative agenda in the House, particularly health care legislation. Medicare, the federal hospital insurance program for persons 65 and older, was initially proposed by the Kennedy Administration as an amendment to the

As Majority Leader, Albert was a key figure in advancing the Democratic legislative agenda in the House, particularly health care legislation. Medicare, the federal hospital insurance program for persons 65 and older, was initially proposed by the Kennedy Administration as an amendment to the  Although well-planned, Albert's efforts on behalf of the Medicare bill were not successful at that time. After Kennedy's assassination, Albert worked to change House rules so that the majority Democrats would have greater influence on the final decisions of Congress under President Lyndon B. Johnson. The changes included more majority leverage over the House Rules Committee and stronger majority membership influence in the House Ways and Means Committee. With these changes in place, Albert was able to push through the Medicare bill, known as the Social Security Act of 1965, and to shepherd other pieces of Johnson's

Although well-planned, Albert's efforts on behalf of the Medicare bill were not successful at that time. After Kennedy's assassination, Albert worked to change House rules so that the majority Democrats would have greater influence on the final decisions of Congress under President Lyndon B. Johnson. The changes included more majority leverage over the House Rules Committee and stronger majority membership influence in the House Ways and Means Committee. With these changes in place, Albert was able to push through the Medicare bill, known as the Social Security Act of 1965, and to shepherd other pieces of Johnson's

Under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Nixon nominated Republican House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to succeed Agnew as vice president in October 1973. As the

Under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Nixon nominated Republican House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to succeed Agnew as vice president in October 1973. As the

The Carl Albert Center at the University of OklahomaCarl Albert Collection

an

Photograph Series

at the Carl Albert Center

Carl Albert State College Home PageThe Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma Home Page

''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'' - Albert, Carl Bert (1908-2000)Oral History Interviews with Carl Albert, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

* * * Retrieved on 2008-02-05 , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Albert, Carl 1908 births 2000 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians Alumni of St Peter's College, Oxford 20th-century American memoirists United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II American Rhodes Scholars Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Oklahoma Majority leaders of the United States House of Representatives Oklahoma lawyers Military personnel from Oklahoma People from McAlester, Oklahoma Speakers of the United States House of Representatives University of Oklahoma alumni United States Army colonels United States Army reservists United States Army Air Forces officers United States Army personnel of World War II

Oklahoma's 3rd congressional district

Oklahoma's 3rd congressional district is the largest congressional district in the state, covering an area of 34,088.49 square miles, over 48 percent the state's land mass. The district is bordered by New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and the Texas ...

as a Democrat from 1947 to 1977.

At tall, Albert was affectionately known as the "Little Giant from Little Dixie". Albert held the highest political office of any Oklahoman in American history.

Early years, education

Albert was born in McAlester, Oklahoma, the son of Leona Ann (Scott) and Ernest Homer Albert, a coal miner and farmer. Shortly after his birth his family moved to Bugtussle, a small town just north of McAlester. He grew up in a log cabin on his father's farm. In high school he excelled in debate, was student body president, and won the national high school oratorical contest, earning a trip to Europe. During this time he was an active member of his local Order of DeMolay chapter; he is an inductee of the Order of DeMolay Hall of Fame. Albert later petitioned his local Masonic Lodge and became an active Freemason. He entered theUniversity of Oklahoma

, mottoeng = "For the benefit of the Citizen and the State"

, type = Public research university

, established =

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.7billion (2021)

, pr ...

in 1927. There, he majored in political science and won the National Oratorical Championship in 1928, receiving an all-expense-paid trip to Europe. He earned enough money to fund the rest of his undergraduate education through working in the college registrar's office and participating in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all ...

. While at Oklahoma, he was an accomplished amateur wrestler, a member of the Kappa Alpha Order fraternity, and a member of the RUF/NEKS

The RUF/NEKS are the nation's oldest all-male spirit squad of its kind for the University of Oklahoma and the 2nd oldest in the world.

History

The earliest years of this student organization are not well known. The RUF/NEKS began in the late 191 ...

. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

in 1931, was the top male student, then studied at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in contin ...

on a Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world ...

. He received a Bachelor of Arts in jurisprudence and Bachelor of Civil Laws from St Peter's College before returning to the United States in 1934. He opened a law practice in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, an ...

in 1935. He worked for a series of oil companies in leasing work until the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

War years

Albert joined theUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

as a private in 1941. He served briefly with the 3rd Armored Division, but was soon commissioned a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until 1 ...

in the Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

. While in the army, Albert married Mary Harmon on August 20, 1942, in Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 census, it is the second-largest city in South Carolina. The city serves as the county seat of Richland County, and a portion of the ci ...

, just before he was sent to the South Pacific.Erin M. Sloan, Albert, Carl Bert (1908-2000)''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. Accessed April 24, 2015. The couple had two children, Mary Frances and David. Albert served in the Judge Advocate General Corps as a prosecutor assigned to the Far East Air Service Command. He earned a

Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious a ...

and other decorations and left the Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1946.Glass, AndrewEx-House Speaker Carl Albert dies, Feb. 4, 2000

Politico.com, February 4, 2011 (accessed April 12, 2014). He remained in the Army Reserve after the war, and retired in 1968 with the rank of

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

.

Enters Congress

Albert was elected to Congress for the first time in 1946. He was a Cold War liberal, and supported President Harry S Truman's containment of Soviet expansionism and domestic measures like public housing, federal aid to education, and farm price supports. Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn noticed his diligence as a legislator and began inviting him to informal meetings in the speaker's office. Rayburn also advised Albert to seek the chairmanship of the Agriculture Committee in 1949. Albert was appointed House Majority Whip in 1955 and electedHouse Majority Leader

Party leaders of the United States House of Representatives, also known as floor leaders, are congresspeople who coordinate legislative initiatives and serve as the chief spokespersons for their parties on the House floor. These leaders are el ...

after Rayburn's death in 1961.

Albert seemed to describe himself as a political moderate. He said, he "very much disliked doctrinaire liberals –– they want to own your minds. And I don't like reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

conservatives. I like to face issues in terms of conditions and not in terms of someone's inborn political philosophy.""The man from Bugtussle made national impact." ''The Norman Transcript''. June 1, 2007.Retrieved May 14, 2014. Albert was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1957.

Congressional majority leader

As Majority Leader, Albert was a key figure in advancing the Democratic legislative agenda in the House, particularly health care legislation. Medicare, the federal hospital insurance program for persons 65 and older, was initially proposed by the Kennedy Administration as an amendment to the

As Majority Leader, Albert was a key figure in advancing the Democratic legislative agenda in the House, particularly health care legislation. Medicare, the federal hospital insurance program for persons 65 and older, was initially proposed by the Kennedy Administration as an amendment to the Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specificall ...

program. Albert knew the bill had insufficient Congressional support for passage due to the opposition of ten Republicans and eight southern Democrats. He advised President Kennedy to seek Senate passage of the measure first. Albert calculated that the Senate should bring it to the House as a conference committee report on their own welfare bill, instead of trying direct introduction into the House.

Although well-planned, Albert's efforts on behalf of the Medicare bill were not successful at that time. After Kennedy's assassination, Albert worked to change House rules so that the majority Democrats would have greater influence on the final decisions of Congress under President Lyndon B. Johnson. The changes included more majority leverage over the House Rules Committee and stronger majority membership influence in the House Ways and Means Committee. With these changes in place, Albert was able to push through the Medicare bill, known as the Social Security Act of 1965, and to shepherd other pieces of Johnson's

Although well-planned, Albert's efforts on behalf of the Medicare bill were not successful at that time. After Kennedy's assassination, Albert worked to change House rules so that the majority Democrats would have greater influence on the final decisions of Congress under President Lyndon B. Johnson. The changes included more majority leverage over the House Rules Committee and stronger majority membership influence in the House Ways and Means Committee. With these changes in place, Albert was able to push through the Medicare bill, known as the Social Security Act of 1965, and to shepherd other pieces of Johnson's Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the University ...

program through Congress. Albert did not sign the 1956 Southern Manifesto, and voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960, 1964, and 1968

The year was highlighted by Protests of 1968, protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – "Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechos ...

, as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

, but voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dw ...

.

Albert also chaired the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus maki ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. The convention was one of the most chaotic in American history. Riots and protests raged outside the venue, and disorder reigned among delegates tasked with leading the party after Johnson's late March decision to not seek reelection, the April assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at 7 ...

, the June assassination of Robert F. Kennedy and the increasing casualties of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

Speaker of U.S. House of Representatives

When Speaker John W. McCormack retired in January 1971, during the second half ofRichard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

's first term as president, Albert was elected Speaker of the House of Representatives.

In September 1972, Albert was witnessed driving drunk and crashing into two cars in the Cleveland Park neighborhood of Washington.

As the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

developed in 1973, Albert, as speaker, referred some two dozen impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

I ...

resolutions to the House Judiciary Committee for debate and study. Also in 1973, he appointed Felda Looper as the first female House page.

In 1973, during Albert's second term as Speaker and Nixon's second term as president, Vice President Spiro Agnew was investigated for tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the tax ...

and money laundering

Money laundering is the process of concealing the origin of money, obtained from illicit activities such as drug trafficking, corruption, embezzlement or gambling, by converting it into a legitimate source. It is a crime in many jurisdiction ...

for a series of bribes he took while he was governor of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

. Agnew resigned as vice president and eventually pleaded '' nolo contendere'' to the charges. This event put Albert next in line to assume the presidency should that office have become vacant.

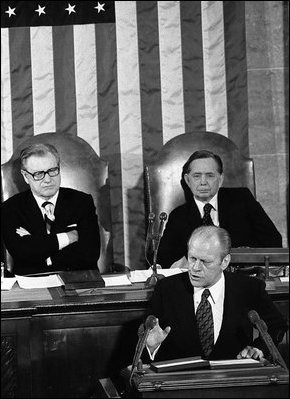

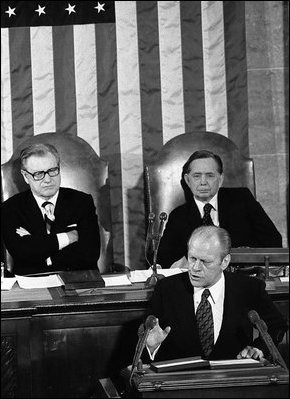

Under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Nixon nominated Republican House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to succeed Agnew as vice president in October 1973. As the

Under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Nixon nominated Republican House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to succeed Agnew as vice president in October 1973. As the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

began to unfold and the impeachment process against Nixon began, it quickly became apparent that if Nixon resigned or was removed from office before Ford was confirmed by both houses, Albert would become acting president under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947

The United States Presidential Succession Act is a federal statute establishing the presidential line of succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact such a statute:

Congress has ...

. Albert would have been forced to resign from the office of Speaker as well as the House.

This was the first occasion since the Twenty-fifth Amendment's ratification when it was possible for a member of one party to assume the presidency after a member of the opposing party vacated the office. As speaker of the House, Albert presided over the only body with the authority to impeach Nixon and had the ability to prevent any vice presidential confirmation vote from taking place in the House. This meant Albert could have maneuvered to make himself acting president. Ted Sorensen prepared a contingency plan for Albert that outlined the steps Albert would have taken had he assumed the presidency. The vice presidency was vacant for about seven weeks; Ford was confirmed and sworn in December 1973.

Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, and the office of vice president was once more left vacant when Ford succeeded Nixon that day. This event put Albert next in line to assume the presidency for a second time. Former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

was nominated by Ford, then confirmed and sworn into office as vice president in December.

A different issue arose during Albert's last term in office when he was confronted with the Tongsun Park scandal. He was accused of accepting gifts and bribes from a lobbyist who was also a member of South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

n intelligence. Albert denied having accepted bribes and admitted receiving only token gifts, which he disclosed. He decided to retire at the end of the 94th Congress

The 94th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1975, ...

in January 1977, and after leaving the House he turned the gifts over to the General Services Administration

The General Services Administration (GSA) is an independent agency of the United States government established in 1949 to help manage and support the basic functioning of federal agencies. GSA supplies products and communications for U.S. gove ...

as required by law. Albert was never charged with a crime.

Retirement

After he left Washington, Albert returned to Bugtussle, turning down many lucrative financial offers from corporate concerns. With help from university professor Danney Goble, Albert published his memoir, ''Little Giant'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 1990, ). A post-retirement editorial in the ''New York Times'' called him "a conciliator and seeker of consensus, a patient persuader . . . trusted for his fairness and integrity." He lectured at the University of Oklahoma and made speeches both in the United States and abroad.Death and legacy

Albert died in McAlester, Oklahoma at the age of 91 on February 4, 2000. He is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in McAlester.Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14000 Famous Persons by Scott Wilson The Carl Albert Center at theUniversity of Oklahoma

, mottoeng = "For the benefit of the Citizen and the State"

, type = Public research university

, established =

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.7billion (2021)

, pr ...

in Norman was established in 1979 for the general purpose of studying Congress and the particular purpose of researching Albert's life and political career. The Center holds the archive of Albert's Congressional papers along with those of Robert S. Kerr, Helen Gahagan Douglas, Millicent Fenwick, Ernest Istook, Fred R. Harris

Fred Roy Harris (born November 13, 1930) is an American academic, author, and former politician who served as a Democratic member of the United States Senate from Oklahoma.

Born in Walters, Oklahoma, Harris was elected to the Oklahoma Senate ...

, Percy Gassaway

Percy Lee Gassaway (August 30, 1885 – May 15, 1937) was an American politician and a U.S. Representative from Oklahoma.

Biography

Born in Waco, McLennan County, Texas, Gassaway was the son of Rev. B. F. and Elizabeth Scoggins Gassaway. He move ...

, and many others. The Congressional Archives hold material from the Civil War era to the present, but the largest portion covers the 1930s to the 1970s.

Carl Albert Indian Health Facility in Ada is part of the Public Health Service and is administered by the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma. Durant

Durant may refer to:

People

* Durant (surname)

Fictional characters

* Durant (Pokémon), a species in ''Pokémon Black'' and ''White''

* ''John Durant'' (General Hospital), a character on the soap opera ''General Hospital''

Places

* Durant, ...

named its Carl Albert Park for him, and a monument to Albert resides at his birthplace in McAlester.

Several institutions and buildings in Oklahoma bear Albert's name. Carl B. Albert Middle School and Carl B. Albert High School in Midwest City

Midwest City is a city in Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, United States, and a part of the Oklahoma City metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the population was 54,371, making it the eighth largest city in the state.

The city was developed in ...

and Carl Albert State College in Poteau are named for him, as well as the Carl Albert Federal Building

The Carl Albert Federal Building is a historic courthouse located in McAlester, Oklahoma. Built in 1914, the facility was renamed in 1985 in honor of former Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, Speaker of the House Carl Albert, ...

in McAlester.

The University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in contin ...

established a monument to Albert in the Eunomia Chambers of the St Peter's College Law Library.

Personal life

Carl Albert married Mary Harmon in 1942; they had a son and a daughter. His cousin Charles W. Vursell served as a member of Congress representing Illinois from 1943 to 1959.References

Further reading

* Albert, Carl. ''Little Giant: The Life and Times of Speaker Carl Albert'' (1990), autobiography, with Danney Goble. * Clark, David W. "Carl Albert: Little Giant of Native America" ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 93#3 (2015) PP 290–311.External links

* The Carl Albert Wikimedia Commons Photograph CollectionThe Carl Albert Center at the University of Oklahoma

an

Photograph Series

at the Carl Albert Center

Carl Albert State College Home Page

''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'' - Albert, Carl Bert (1908-2000)

* * * Retrieved on 2008-02-05 , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Albert, Carl 1908 births 2000 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians Alumni of St Peter's College, Oxford 20th-century American memoirists United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II American Rhodes Scholars Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Oklahoma Majority leaders of the United States House of Representatives Oklahoma lawyers Military personnel from Oklahoma People from McAlester, Oklahoma Speakers of the United States House of Representatives University of Oklahoma alumni United States Army colonels United States Army reservists United States Army Air Forces officers United States Army personnel of World War II