Camera Obscura (2010 Film) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or

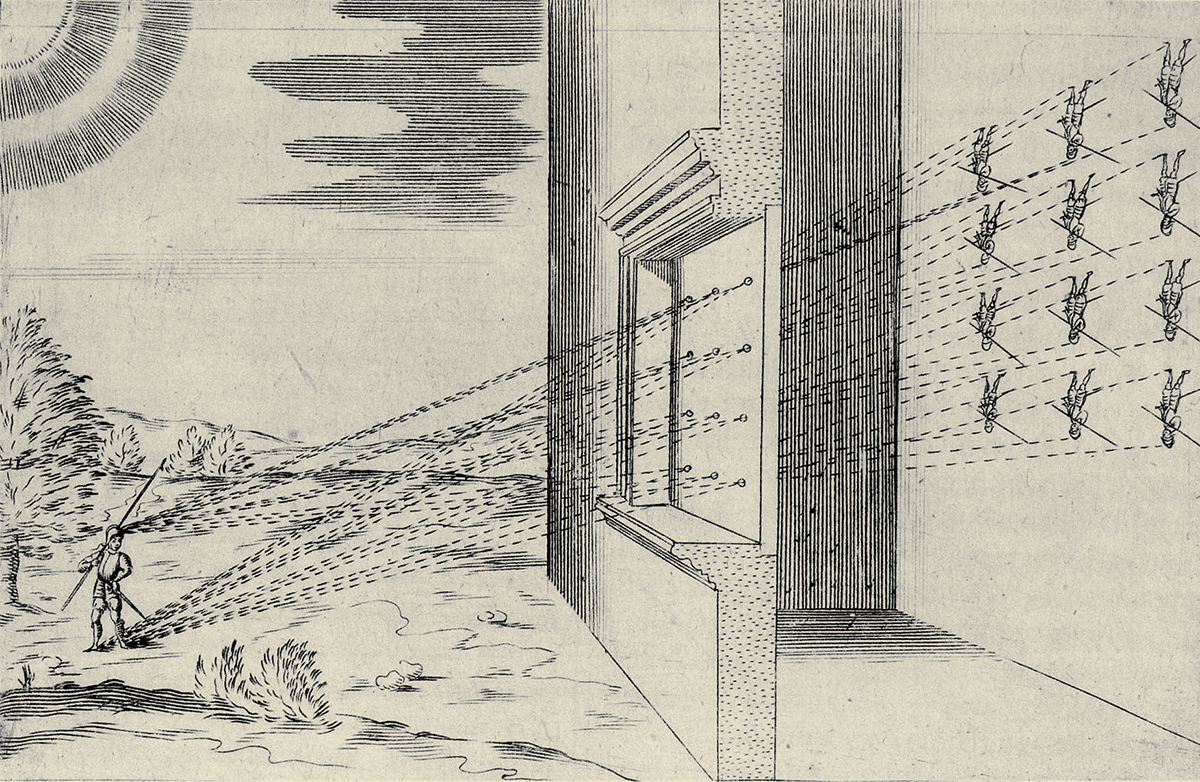

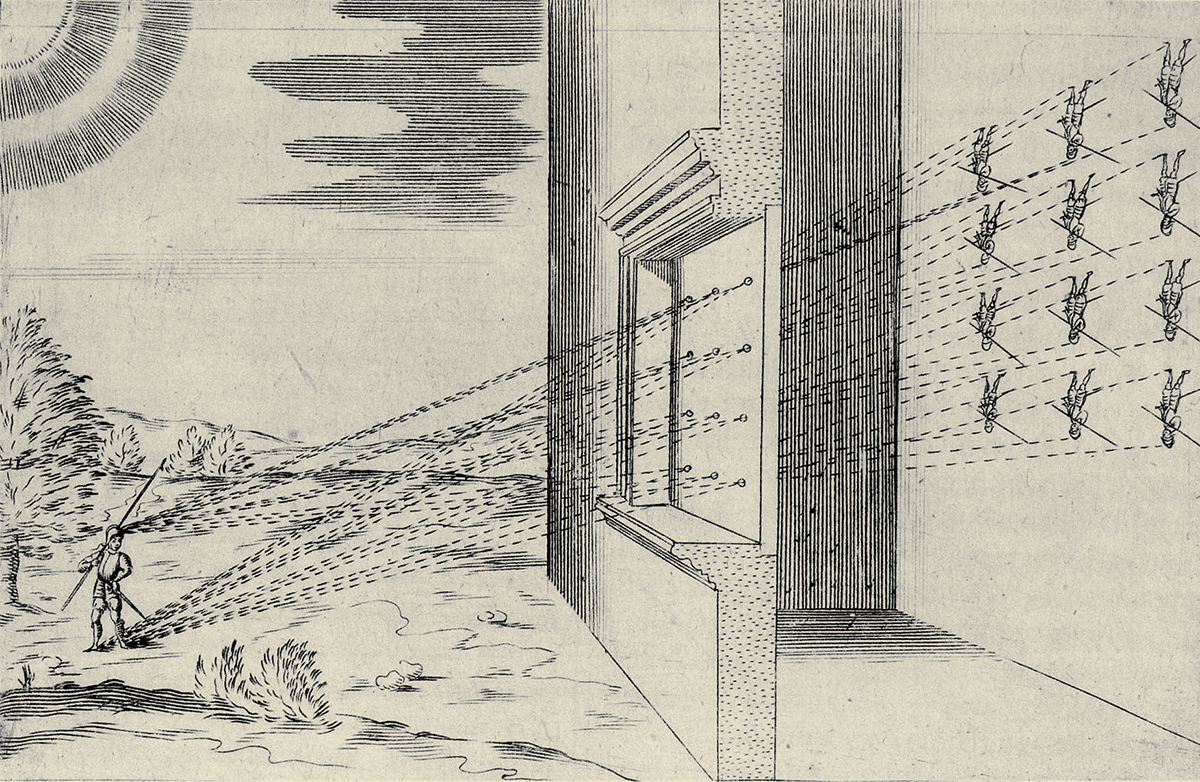

A camera obscura consists of a box, tent, or room with a small hole in one side or the top. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside, where the scene is reproduced, inverted (upside-down) and reversed (left to right), but with color and perspective preserved.

To produce a reasonably clear projected image, the aperture is typically smaller than 1/100th the distance to the screen.

As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but dimmer. With a too small pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to

A camera obscura consists of a box, tent, or room with a small hole in one side or the top. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside, where the scene is reproduced, inverted (upside-down) and reversed (left to right), but with color and perspective preserved.

To produce a reasonably clear projected image, the aperture is typically smaller than 1/100th the distance to the screen.

As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but dimmer. With a too small pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to

Perforated

Perforated

In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect

In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect

English philosopher and Franciscan friar

English philosopher and Franciscan friar

Italian polymath

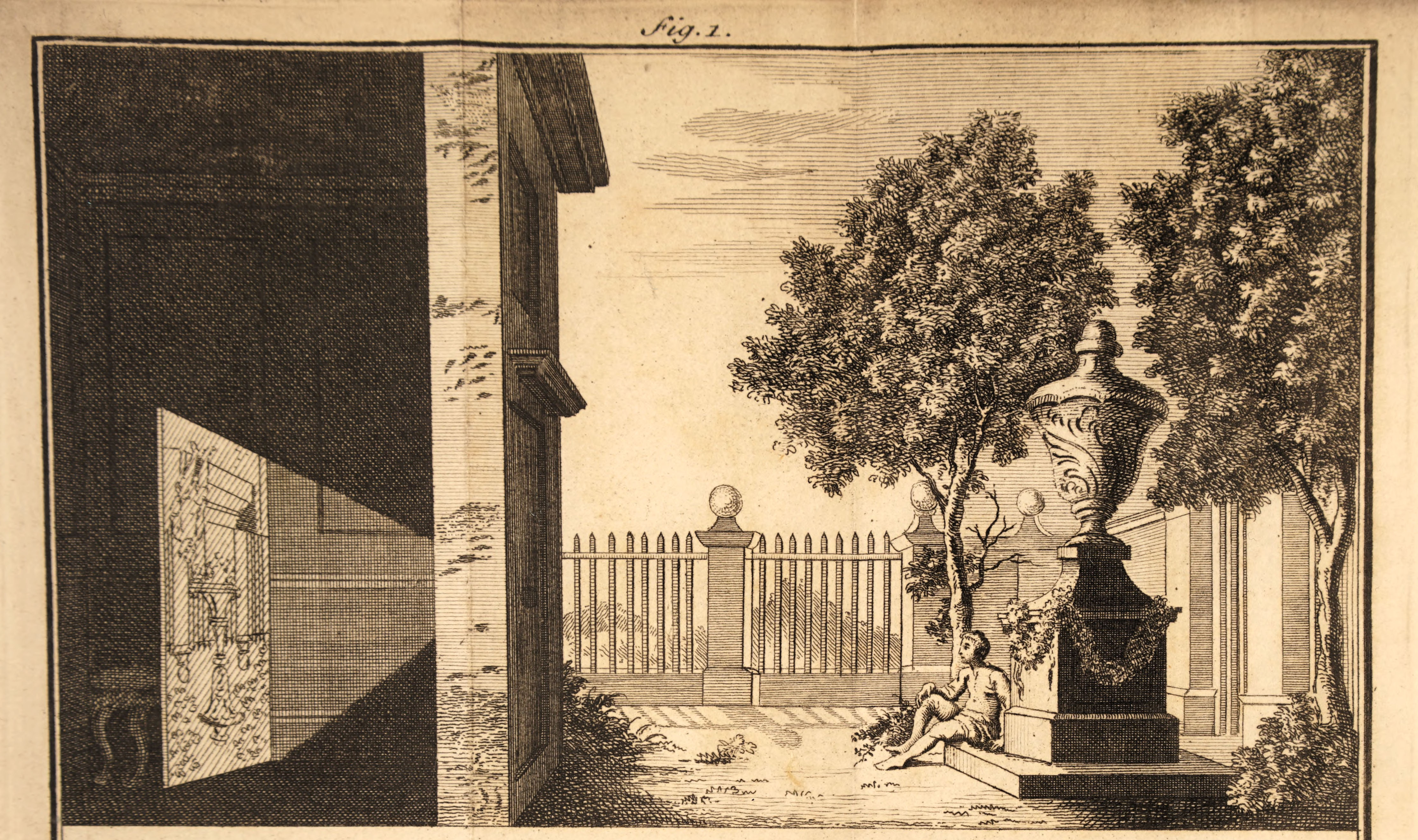

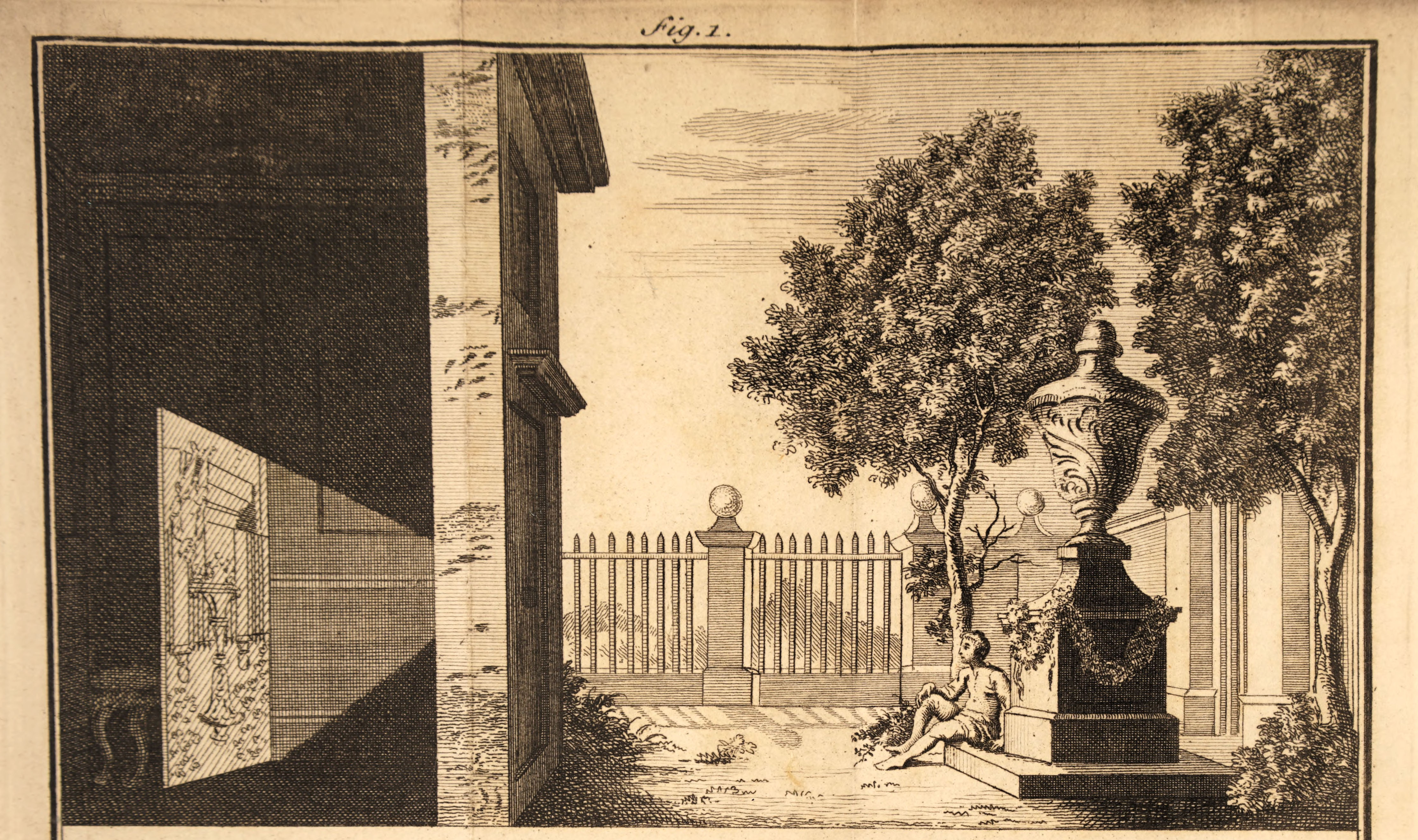

Italian polymath  The oldest known published drawing of a camera obscura is found in Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker

The oldest known published drawing of a camera obscura is found in Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker  In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, (1572), German mathematician

In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, (1572), German mathematician

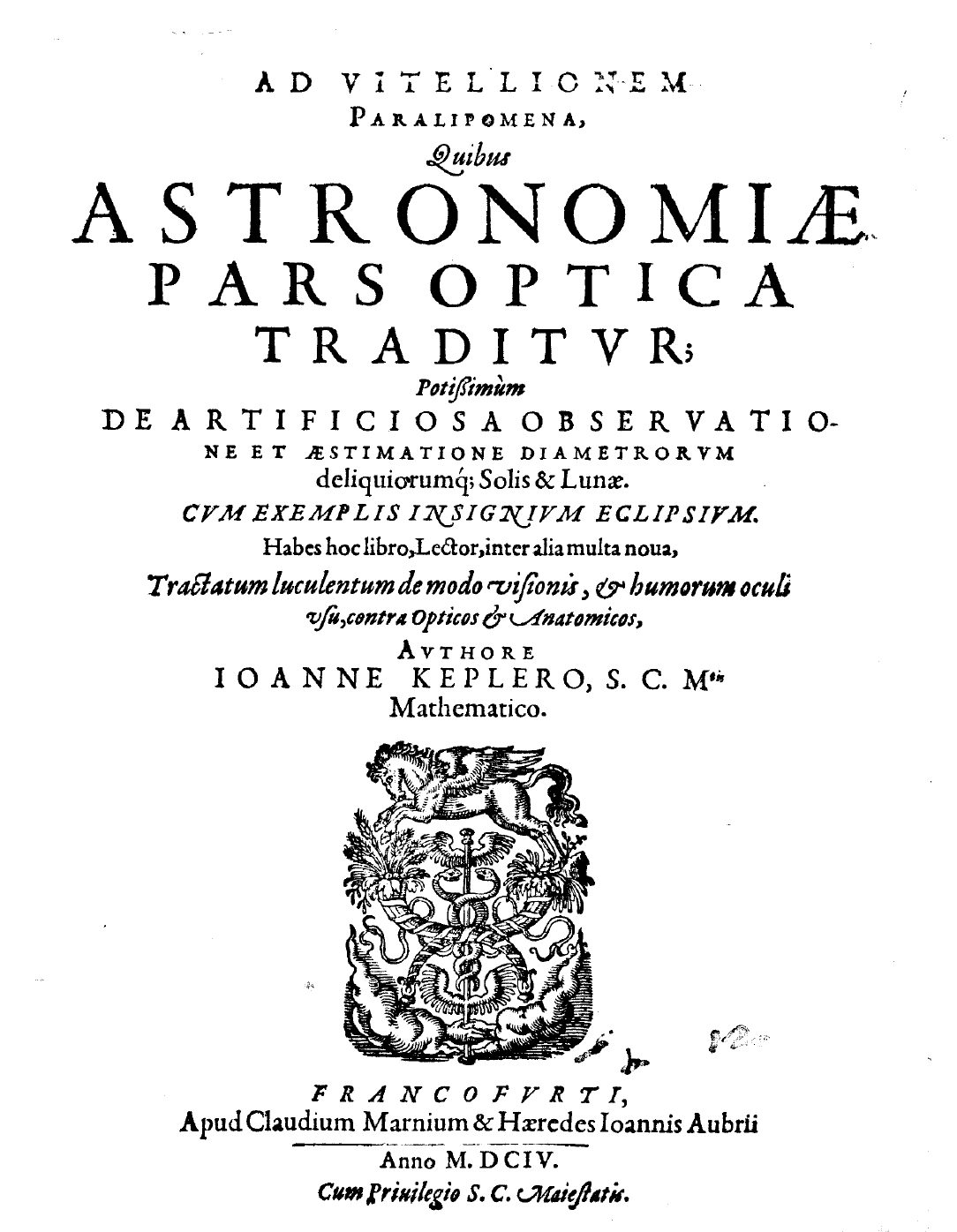

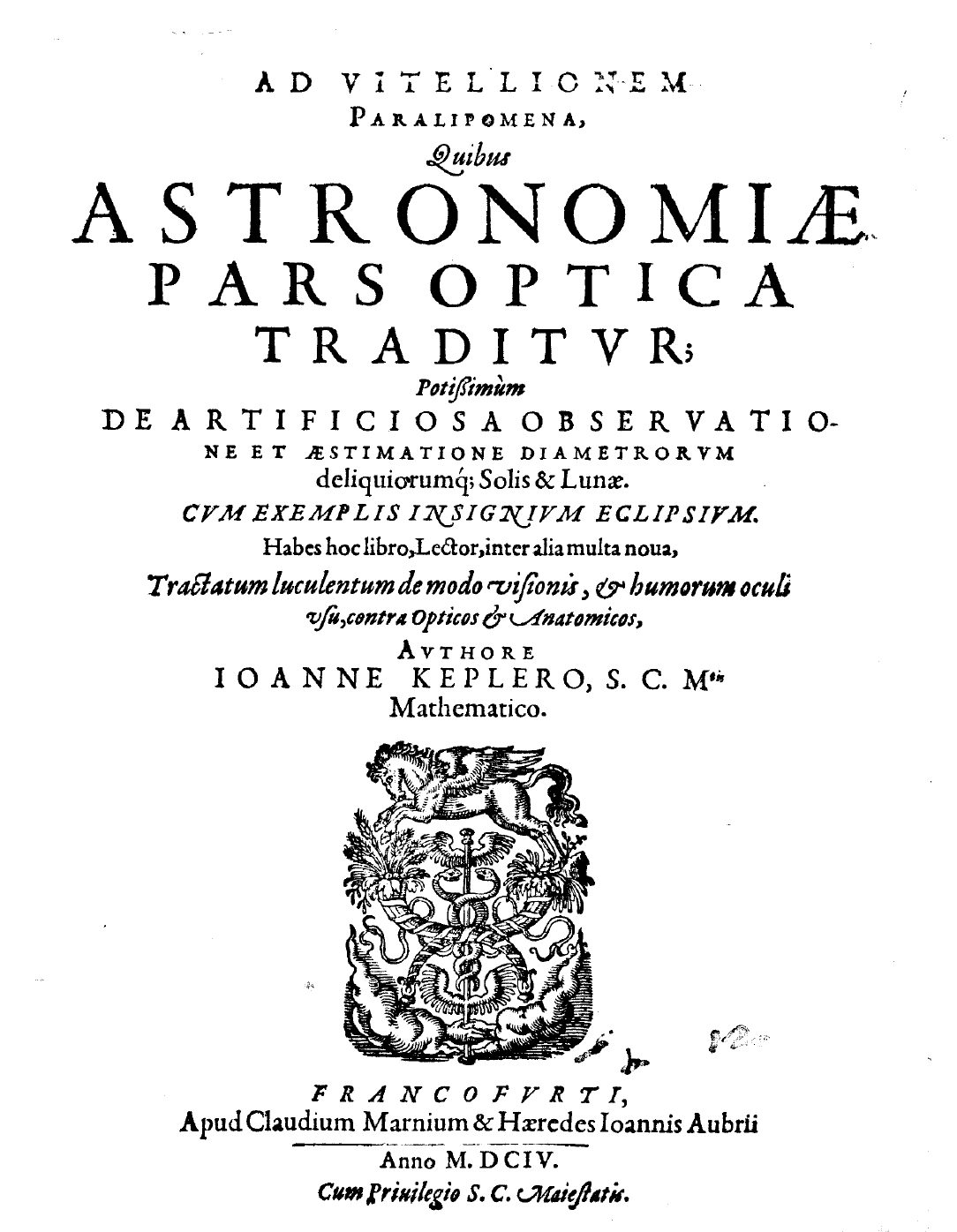

The earliest use of the term "camera obscura" is found in the 1604 book ''Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena'' by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer

The earliest use of the term "camera obscura" is found in the 1604 book ''Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena'' by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer  From 1612 to at least 1630,

From 1612 to at least 1630,  By 1620 Kepler used a portable camera obscura tent with a modified telescope to draw landscapes. It could be turned around to capture the surroundings in parts.

Dutch inventor

By 1620 Kepler used a portable camera obscura tent with a modified telescope to draw landscapes. It could be turned around to capture the surroundings in parts.

Dutch inventor  German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian

German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian  Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer

Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer

German philosopher

German philosopher

While the technical principles of the camera obscura have been known since antiquity, the broad use of the technical concept in producing images with a

While the technical principles of the camera obscura have been known since antiquity, the broad use of the technical concept in producing images with a

File:CameraObscura.JPG, A freestanding room-sized camera obscura at the

*

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

at one side through which an image

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensiona ...

is projected

Projected is an American rock supergroup consisting of Sevendust members John Connolly and Vinnie Hornsby, Alter Bridge and Creed drummer Scott Phillips, and former Submersed and current Tremonti guitarist Eric Friedman. The band released thei ...

onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions such as a box or tent in which an exterior image is projected inside. Camera obscuras with a lens in the opening have been used since the second half of the 16th century and became popular as aids for drawing and painting. The concept was developed further into the photographic camera

A camera is an Optics, optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), ...

in the first half of the 19th century, when camera obscura boxes were used to expose

Expose, exposé, or exposed may refer to:

News sources

* Exposé (journalism), a form of investigative journalism

* '' The Exposé'', a British conspiracist website

Film and TV Film

* ''Exposé'' (film), a 1976 thriller film

* ''Exposed'' (1932 ...

light-sensitive materials to the projected image.

The camera obscura was used to study eclipses without the risk of damaging the eyes by looking directly into the sun. As a drawing aid, it allowed tracing the projected image to produce a highly accurate representation, and was especially appreciated as an easy way to achieve proper graphical perspective

Linear or point-projection perspective (from la, perspicere 'to see through') is one of two types of graphical projection perspective in the graphic arts; the other is parallel projection. Linear perspective is an approximate representation, ...

.

Before the term ''camera obscura'' was first used in 1604, other terms were used to refer to the devices: ''cubiculum obscurum'', ''cubiculum tenebricosum'', ''conclave obscurum'', and ''locus obscurus''.

A camera obscura without a lens but with a very small hole is sometimes referred to as a pinhole camera

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called ''pinhole'')—effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image o ...

, although this more often refers to simple (homemade) lensless cameras where photographic film or photographic paper is used.

Physical explanation

Rays of light travel in straight lines and change when they are reflected and partly absorbed by an object, retaining information about the color and brightness of the surface of that object. Lighted objects reflect rays of light in all directions. A small enough opening in a barrier admits only the rays that travel directly from different points in the scene on the other side, and these rays form an image of that scene where they reach a surface opposite from the opening. Thehuman eye

The human eye is a sensory organ, part of the sensory nervous system, that reacts to visible light and allows humans to use visual information for various purposes including seeing things, keeping balance, and maintaining circadian rhythm.

...

(and those of animals such as birds, fish, reptiles etc.) works much like a camera obscura with an opening (pupil

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company. It appears black ...

), a convex lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

, and a surface where the image is formed (retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

). Some cameras obscura use a concave mirror for a focusing effect similar to a convex lens.

Technology

A camera obscura consists of a box, tent, or room with a small hole in one side or the top. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside, where the scene is reproduced, inverted (upside-down) and reversed (left to right), but with color and perspective preserved.

To produce a reasonably clear projected image, the aperture is typically smaller than 1/100th the distance to the screen.

As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but dimmer. With a too small pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to

A camera obscura consists of a box, tent, or room with a small hole in one side or the top. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside, where the scene is reproduced, inverted (upside-down) and reversed (left to right), but with color and perspective preserved.

To produce a reasonably clear projected image, the aperture is typically smaller than 1/100th the distance to the screen.

As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but dimmer. With a too small pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to diffraction

Diffraction is defined as the interference or bending of waves around the corners of an obstacle or through an aperture into the region of geometrical shadow of the obstacle/aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a s ...

. Optimum sharpness is attained with an aperture diameter approximately equal to the geometric mean of the wavelength of light and the distance to the screen.

In practice, camera obscuras use a lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

rather than a pinhole because it allows a larger aperture

In optics, an aperture is a hole or an opening through which light travels. More specifically, the aperture and focal length of an optical system determine the cone angle of a bundle of rays that come to a focus in the image plane.

An opt ...

, giving a usable brightness while maintaining focus.

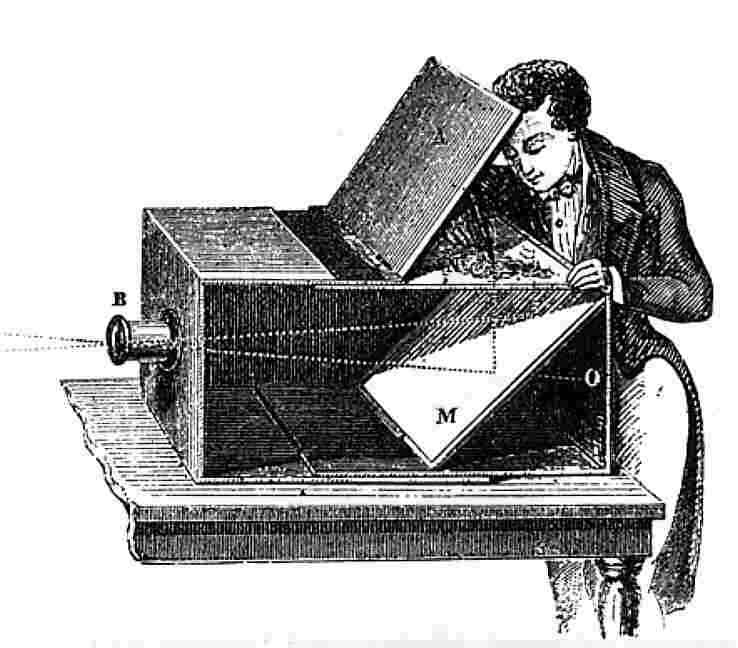

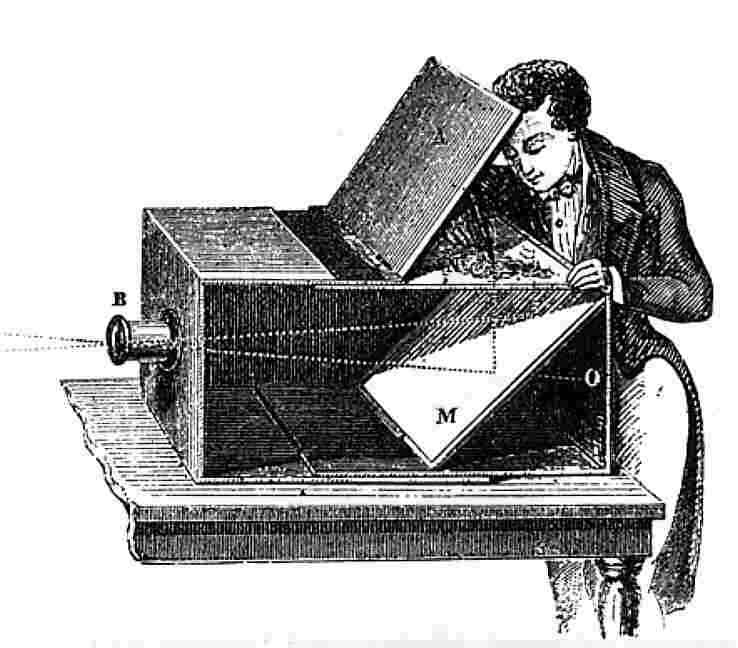

If the image is caught on a translucent screen, it can be viewed from the back so that it is no longer reversed (but still upside-down). Using mirrors, it is possible to project a right-side-up image. The projection can also be displayed on a horizontal surface (e.g., a table). The 18th-century overhead version in tents used mirrors inside a kind of periscope on the top of the tent.

The box-type camera obscura often has an angled mirror projecting an upright image onto tracing paper

Tracing paper is paper made to have low opacity, allowing light to pass through. It was originally developed for architects and design engineers to create drawings that could be copied precisely using the diazo copy process; it then found ma ...

placed on its glass top. Although the image is viewed from the back, it is reversed by the mirror.

History

Prehistory to 500 BC: Possible inspiration for prehistoric art and possible use in religious ceremonies, gnomons

There are theories that occurrences of camera obscura effects (through tiny holes in tents or in screens of animal hide) inspiredpaleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

cave painting

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

s. Distortions in the shapes of animals in many paleolithic cave artworks might be inspired by distortions seen when the surface on which an image was projected was not straight or not in the right angle.

It is also suggested that camera obscura projections could have played a role in Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

structures.

gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ol ...

s projecting a pinhole image of the sun were described in the Chinese ''Zhoubi Suanjing

The ''Zhoubi Suanjing'' () is one of the oldest Chinese mathematical texts. "Zhou" refers to the ancient Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE); "Bì" literally means "thigh", but in the book refers to the gnomon of a sundial. The book is dedicated to ...

'' writings (1046 BC–256 BC with material added until circa 220 AD). The location of the bright circle can be measured to tell the time of day and year. In Arab and European cultures its invention was much later attributed to Egyptian astronomer and mathematician Ibn Yunus

Abu al-Hasan 'Ali ibn 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Ahmad ibn Yunus al-Sadafi al-Misri (Arabic: ابن يونس; c. 950 – 1009) was an important Egyptians, Egyptian astronomer and Islamic mathematics, mathematician, whose works are noted for being ahead o ...

around 1000 AD.

500 BC to 500 AD: Earliest written observations

One of the earliest known written records of apinhole camera

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called ''pinhole'')—effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image o ...

for camera obscura effect is found in the Chinese text called ''Mozi

Mozi (; ; Latinized as Micius ; – ), original name Mo Di (), was a Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (the early portion of the Warring States period, –221 BCE). The ancie ...

'', dated to the 4th century BC, traditionally ascribed to and named for Mozi

Mozi (; ; Latinized as Micius ; – ), original name Mo Di (), was a Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (the early portion of the Warring States period, –221 BCE). The ancie ...

(circa 470 BC-circa 391 BC), a Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

philosopher and the founder of Mohist School of Logic. These writings explain how the image in a "collecting-point" or "treasure house"In the ''Mozi'' passage, a camera obscura is described as a "collecting-point" or "treasure house" ( 庫); the 18th-century scholar Bi Yuan () suggested this was a misprint for "screen" ( 㢓). is inverted by an intersecting point (pinhole) that collects the (rays of) light. Light coming from the foot of an illuminated person were partly hidden below (i.e., strike below the pinhole) and partly formed the top of the image. Rays from the head were partly hidden above (i.e., strike above the pinhole) and partly formed the lower part of the image.

Another early account is provided by Greek philosopher

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(384–322 BC), or possibly a follower of his ideas. Similar to the later 11th-century Arab scientist Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

, Aristotle is also thought to have used camera obscura for observing solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

s. Camera obscura is touched upon as a subject in Aristotle's work ''Problems

A problem is a difficulty which may be resolved by problem solving.

Problem(s) or The Problem may also refer to:

People

* Problem (rapper), (born 1985) American rapper Books

* Problems (Aristotle), ''Problems'' (Aristotle), an Aristotelian (or ps ...

– Book XV'', asking: and further on:

Many philosophers and scientists of the Western world pondered this question before it was accepted that the circular and crescent-shapes described in the "problem" were pinhole image projections of the sun. Although a projected image has the shape of the aperture when the light source, aperture and projection plane are close together, the projected image has the shape of the light source when they are farther apart.

In his book ''Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

'' (circa 300 BC, surviving in later manuscripts from around 1000 AD), Euclid proposed mathematical descriptions of vision with "lines drawn directly from the eye pass through a space of great extent" and "the form of the space included in our vision is a cone, with its apex in the eye and its base at the limits of our vision." Later versions of the text, like Ignazio Danti

Ignazio (Egnation or Egnazio) Danti, O.P. (April 1536 – 10 October 1586), born Pellegrino Rainaldi Danti, was an Italian Roman Catholic prelate, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer, who served as Bishop of Alatri (1583–1586). ''(in ...

's 1573 annotated translation, would add a description of the camera obscura principle to demonstrate Euclid's ideas.

500 to 1000: Earliest experiments, study of light

In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect

In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles

Anthemius of Tralles ( grc-gre, Ἀνθέμιος ὁ Τραλλιανός, Medieval Greek: , ''Anthémios o Trallianós''; – 533 558) was a Greek from Tralles who worked as a geometer and architect in Constantinople, the capit ...

(most famous as a co-architect of the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

) experimented with effects related to the camera obscura.G. Huxley (1959) ''Anthemius of Tralles: a study of later Greek Geometry'' pp. 6–8, pp.44–46 as cited in , p.205 Anthemius had a sophisticated understanding of the involved optics, as demonstrated by a light-ray diagram he constructed in 555 AD.

In the 10th century

The 10th century was the period from 901 ( CMI) through 1000 ( M) in accordance with the Julian calendar, and the last century of the 1st millennium.

In China the Song dynasty was established. The Muslim World experienced a cultural zenith, ...

Yu Chao-Lung supposedly projected images of pagoda models through a small hole onto a screen to study directions and divergence of rays of light.

1000 to 1400: Optical and astronomical tool, entertainment

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(known in the West by the Latinised Alhazen) (965–1040) extensively studied the camera obscura phenomenon in the early 11th century.

In his treatise "On the shape of the eclipse" he provided the first experimental and mathematical analysis of the phenomenon.

He must have understood the relationship between the focal point

Focal point may refer to:

* Focus (optics)

* Focus (geometry)

* Conjugate points, also called focal points

* Focal point (game theory)

* Unicom Focal Point, a portfolio management software tool

* Focal point review, a human resources process for ...

and the pinhole.

In his ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' ( ar, كتاب المناظر, Kitāb al-Manāẓir; la, De Aspectibus or ''Perspectiva''; it, Deli Aspecti) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al- ...

'' (circa 1027), Ibn al-Haytham explained that rays of light travel in straight lines and are distinguished by the body that reflected the rays, writing:

He described a "dark chamber", and experimented with light passing through small pinholes, using three adjacent candles and seeing the effects on the wall after placing a cutout between the candles and the wall.

Ibn al-Haytham also analyzed the rays of sunlight and concluded that they made a conic shape where they met at the hole, forming another conic shape reverse to the first one from the hole to the opposite wall in the dark room. Latin translations of his writings on optics were very influential in Europe from about 1200 onward. Among those he inspired were Witelo

Vitello ( pl, Witelon; german: Witelo; – 1280/1314) was a friar, theologian, natural philosopher and an important figure in the history of philosophy in Poland.

Name

Vitello's name varies with some sources. In earlier publications he was quo ...

, John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under B ...

, Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

, René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

and Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

.

In his 1088 book, ''Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

'', the Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

Chinese scientist Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031–1095) compared the focal point of a concave burning-mirror and the "collecting" hole of camera obscura phenomena to an oar in a rowlock to explain how the images were inverted:

Shen Kuo also responded to a statement of Duan Chengshi

Duan Chengshi () (died 863) was a Chinese poet and writer of the Tang Dynasty. He was born to a wealthy family in present-day Zibo, Shandong. A descendant of the early Tang official Duan Zhixuan (, ''Duàn Zhìxuán'') (-642), and the son of Duan ...

in ''Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang

The ''Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang'' () is a book written by Duan Chengshi in the 9th century. It focuses on miscellany of Chinese and foreign legends and hearsay, reports on natural phenomena, short anecdotes, and tales of the wondrous an ...

'' written in about 840 that the inverted image of a Chinese pagoda

A pagoda is an Asian tiered tower with multiple eaves common to Nepal, India, China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most often Buddhist but sometimes Taoist, ...

tower beside a seashore, was inverted because it was reflected by the sea: "This is nonsense. It is a normal principle that the image is inverted after passing through the small hole."

English statesman and scholastic philosopher

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a Organon, critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelianism, Aristotelian categories (Aristotle), 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism eme ...

Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste, ', ', or ') or the gallicised Robert Grosstête ( ; la, Robertus Grossetesta or '). Also known as Robert of Lincoln ( la, Robertus Lincolniensis, ', &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln ( la, Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.). ( ; la, Rob ...

(c. 1175 – 9 October 1253) was one of the earliest Europeans who commented on the camera obscura.

English philosopher and Franciscan friar

English philosopher and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

(c. 1219/20 – c. 1292) falsely stated in his ''De Multiplicatione Specerium'' (1267) that an image projected through a square aperture was round because light would travel in spherical waves and therefore assumed its natural shape after passing through a hole. He is also credited with a manuscript that advised to study solar eclipses safely by observing the rays passing through some round hole and studying the spot of light they form on a surface.

A picture of a three-tiered camera obscura (see illustration) has been attributed to Bacon, but the source for this attribution is not given. A very similar picture is found in Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans ...

's ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' ("The Great Art of Light and Shadow") is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was pub ...

'' (1646).

Polish friar, theologian, physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher Erazmus Ciołek Witelo (also known as Vitello Thuringopolonis and by many different spellings of the name "Witelo") wrote about the camera obscura in his very influential treatise ''Perspectiva'' (circa 1270–1278), which was largely based on Ibn al-Haytham's work.

English archbishop and scholar John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under B ...

(circa 1230 – 1292) wrote about the camera obscura in his ''Tractatus de Perspectiva'' (circa 1269–1277) and ''Perspectiva communis'' (circa 1277–79), falsely arguing that light gradually forms the circular shape after passing through the aperture. His writings were influenced by Roger Bacon.

At the end of the 13th century, Arnaldus de Villa Nova

Arnaldus de Villa Nova (also called Arnau de Vilanova in Catalan, his language, Arnaldus Villanovanus, Arnaud de Ville-Neuve or Arnaldo de Villanueva, c. 1240–1311) was a physician and a religious reformer. He was also thought to be an alchem ...

is credited with using a camera obscura to project live performances for entertainment.

French astronomer Guillaume de Saint-Cloud suggested in his 1292 work ''Almanach Planetarum'' that the eccentricity of the sun could be determined with the camera obscura from the inverse proportion between the distances and the apparent solar diameters at apogee and perigee.

Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī

Kamal al-Din Hasan ibn Ali ibn Hasan al-Farisi or Abu Hasan Muhammad ibn Hasan (1267– 12 January 1319, long assumed to be 1320)) ( fa, كمالالدين فارسی) was a Persian Muslim scientist. He made two major contributions to scienc ...

(1267–1319) described in his 1309 work ''Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir'' (''The Revision of the Optics'') how he experimented with a glass sphere filled with water in a camera obscura with a controlled aperture and found that the colors of the rainbow are phenomena of the decomposition of light.

French Jewish philosopher, mathematician, physicist and astronomer/astrologer Levi ben Gershon

Levi ben Gershon (1288 – 20 April 1344), better known by his Graecized name as Gersonides, or by his Latinized name Magister Leo Hebraeus, or in Hebrew by the abbreviation of first letters as ''RaLBaG'', was a medieval French Jewish philosoph ...

(1288–1344) (also known as Gersonides or Leo de Balneolis) made several astronomical observations using a camera obscura with a Jacob's staff

The term Jacob's staff is used to refer to several things, also known as cross-staff, a ballastella, a fore-staff, a ballestilla, or a balestilha. In its most basic form, a Jacob's staff is a stick or pole with length markings; most staffs ar ...

, describing methods to measure the angular diameters of the sun, the moon and the bright planets Venus and Jupiter. He determined the eccentricity of the sun based on his observations of the summer and winter solstices in 1334. Levi also noted how the size of the aperture determined the size of the projected image. He wrote about his findings in Hebrew in his treatise ''Sefer Milhamot Ha-Shem'' (''The Wars of the Lord'') Book V Chapters 5 and 9.

1450 to 1600: Depiction, lenses, drawing aid, mirrors

Italian polymath

Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

(1452–1519), familiar with the work of Alhazen in Latin translation, and after an extensive study of optics and human vision, wrote the oldest known clear description of the camera obscura in mirror writing in a notebook in 1502, later published in the collection ''Codex Atlanticus

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a 12-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest single set. Its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was us ...

'' (translated from Latin):

These descriptions, however, would remain unknown until Venturi deciphered and published them in 1797.

Da Vinci was clearly very interested in the camera obscura: over the years he drew circa 270 diagrams of the camera obscura in his notebooks . He systematically experimented with various shapes and sizes of apertures and with multiple apertures (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, 24, 28 and 32). He compared the working of the eye to that of the camera obscura and seemed especially interested in its capability of demonstrating basic principles of optics: the inversion of images through the pinhole or pupil, the non-interference of images and the fact that images are "all in all and all in every part".

The oldest known published drawing of a camera obscura is found in Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker

The oldest known published drawing of a camera obscura is found in Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker Gemma Frisius

Gemma Frisius (; born Jemme Reinerszoon; December 9, 1508 – May 25, 1555) was a Frisian physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker. He created important globes, improved the mathematical instruments of his d ...

’ 1545 book ''De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica'', in which he described and illustrated how he used the camera obscura to study the solar eclipse of 24 January 1544

Italian polymath Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano (; also Girolamo or Geronimo; french: link=no, Jérôme Cardan; la, Hieronymus Cardanus; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath, whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, ...

described using a glass disc – probably a biconvex lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

– in a camera obscura in his 1550 book ''De subtilitate, vol. I, Libri IV''. He suggested to use it to view "what takes place in the street when the sun shines" and advised to use a very white sheet of paper as a projection screen so the colours wouldn't be dull.

Sicilian mathematician and astronomer Francesco Maurolico

Francesco Maurolico (Latin: ''Franciscus Maurolycus''; Italian: ''Francesco Maurolico''; gr, Φραγκίσκος Μαυρόλυκος, 16 September 1494 - 21/22 July 1575) was a mathematician and astronomer from Sicily. He made contributions t ...

(1494–1575) answered Aristotle's problem how sunlight that shines through rectangular holes can form round spots of light or crescent-shaped spots during an eclipse in his treatise ''Photismi de lumine et umbra'' (1521–1554). However this wasn't published before 1611, after Johannes Kepler had published similar findings of his own.

Italian polymath Giambattista della Porta

Giambattista della Porta (; 1535 – 4 February 1615), also known as Giovanni Battista Della Porta, was an Italian scholar, polymath and playwright who lived in Naples at the time of the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution and Reformation.

Giamba ...

described the camera obscura, which he called "obscurum cubiculum", in the 1558 first edition of his book series ''Magia Naturalis

' (in English, ''Natural Magic'') is a work of popular science by Giambattista della Porta first published in Naples in 1558. Its popularity ensured it was republished in five Latin editions within ten years, with translations into Italian (1560 ...

''. He suggested to use a convex lens to project the image onto paper and to use this as a drawing aid. Della Porta compared the human eye to the camera obscura: "For the image is let into the eye through the eyeball just as here through the window". The popularity of Della Porta's books helped spread knowledge of the camera obscura.

In his 1567 work ''La Pratica della Perspettiva'' Venetian nobleman Daniele Barbaro

Daniele Matteo Alvise Barbaro (also Barbarus) (8 February 1514 – 13 April 1570) was an Italian cleric and diplomat. He was also an architect, writer on architecture, and translator of, and commentator on, Vitruvius.

Barbaro's fame is chief ...

(1513-1570) described using a camera obscura with a biconvex lens as a drawing aid and points out that the picture is more vivid if the lens is covered as much as to leave a circumference in the middle.

In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, (1572), German mathematician

In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, (1572), German mathematician Friedrich Risner

Friedrich Risner (c.1533 – 15 September 1580) (in Latin Fridericus Risnerus) was a German mathematician from Hersfeld, Hesse. He was an assistant to Petrus Ramus (from around 1565) and was the first chair of mathematics at Collège Royale d ...

proposed a portable camera obscura drawing aid; a lightweight wooden hut with lenses in each of its four walls that would project images of the surroundings on a paper cube in the middle. The construction could be carried on two wooden poles. A very similar setup was illustrated in 1645 in Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans ...

's influential book ''Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae''.

Around 1575 Italian Dominican priest, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer Ignazio Danti

Ignazio (Egnation or Egnazio) Danti, O.P. (April 1536 – 10 October 1586), born Pellegrino Rainaldi Danti, was an Italian Roman Catholic prelate, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer, who served as Bishop of Alatri (1583–1586). ''(in ...

designed a camera obscura gnomon and a meridian line for the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella

Santa Maria Novella is a church in Florence, Italy, situated opposite, and lending its name to, the city's main railway station. Chronologically, it is the first great basilica in Florence, and is the city's principal Dominican church.

The chu ...

, Florence and he later had a massive gnomon built in the San Petronio Basilica

The Basilica of San Petronio is a minor basilica and church of the Archdiocese of Bologna located in Bologna, Emilia Romagna, northern Italy. It dominates Piazza Maggiore. The basilica is dedicated to the patron saint of the city, Saint Petronius ...

in Bologna. The gnomon was used to study the movements of the sun during the year and helped in determining the new Gregorian calendar for which Danti took place in the commission appointed by Pope Gregorius XIII and instituted in 1582.

In his 1585 book ''Diversarum Speculationum Mathematicarum'' Venetian mathematician Giambattista Benedetti

Giambattista (Gianbattista) Benedetti (August 14, 1530 – January 20, 1590 in) was an Italian mathematician from Venice who was also interested in physics, mechanics, the construction of sundials, and the science of music.

Science of motio ...

proposed to use a mirror in a 45-degree angle to project the image upright. This leaves the image reversed, but would become common practice in later camera obscura boxes.

Giambattista della Porta added a "lenticular crystal" or biconvex lens to the camera obscura description in the 1589 second edition of ''Magia Naturalis''. He also described use of the camera obscura to project hunting scenes, banquets, battles, plays, or anything desired on white sheets. Trees, forests, rivers, mountains "that are really so, or made by Art, of Wood, or some other matter" could be arranged on a plain in the sunshine on the other side of the camera obscura wall. Little children and animals (for instance handmade deer, wild boars, rhinos, elephants, and lions) could perform in this set. "Then, by degrees, they must appear, as coming out of their dens, upon the Plain: The Hunter he must come with his hunting Pole, Nets, Arrows, and other necessaries, that may represent hunting: Let there be Horns, Cornets, Trumpets sounded: those that are in the Chamber shall see Trees, Animals, Hunters Faces, and all the rest so plainly, that they cannot tell whether they be true or delusions: Swords drawn will glister in at the hole, that they will make people almost afraid."

Della Porta claimed to have shown such spectacles often to his friends. They admired it very much and could hardly be convinced by Della Porta's explanations that what they had seen was really an optical trick.

1600 to 1650: Name coined, camera obscura telescopy, portable drawing aid in tents and boxes

The earliest use of the term "camera obscura" is found in the 1604 book ''Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena'' by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer

The earliest use of the term "camera obscura" is found in the 1604 book ''Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena'' by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

. Kepler discovered the working of the camera obscura by recreating its principle with a book replacing a shining body and sending threads from its edges through a many-cornered aperture in a table onto the floor where the threads recreated the shape of the book. He also realized that images are "painted" inverted and reversed on the retina of the eye and figured that this is somehow corrected by the brain.

In 1607, Kepler studied the sun in his camera obscura and noticed a sunspot

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. Sun ...

, but he thought it was Mercury transiting the sun.

In his 1611 book ''Dioptrice'', Kepler described how the projected image of the camera obscura can be improved and reverted with a lens. It is believed he later used a telescope with three lenses to revert the image in the camera obscura.

In 1611, Frisian/German astronomers David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

and Johannes Fabricius

Johann Goldsmid, better known by his Latinized name Johann(es) Fabricius (8 January 1587 – 19 March 1616), eldest son of David Fabricius (1564–1617), was a Frisian/German astronomer and a discoverer of sunspots (in 1610), independently of Ga ...

(father and son) studied sunspots with a camera obscura, after realizing looking at the sun directly with the telescope could damage their eyes. They are thought to have combined the telescope and the camera obscura into camera obscura telescopy.

In 1612, Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli

Benedetto Castelli (1578 – 9 April 1643), born Antonio Castelli, was an Italian mathematician. Benedetto was his name in religion on entering the Benedictine Order in 1595.

Life

Born in Brescia, Castelli studied at the University of Padua and l ...

wrote to his mentor, the Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher, and mathematician Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

about projecting images of the sun through a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

(invented in 1608) to study the recently discovered sunspots. Galilei wrote about Castelli's technique to the German Jesuit priest, physicist, and astronomer Christoph Scheiner.

From 1612 to at least 1630,

From 1612 to at least 1630, Christoph Scheiner

Christoph Scheiner SJ (25 July 1573 (or 1575) – 18 June 1650) was a Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer in Ingolstadt.

Biography Augsburg/Dillingen: 1591–1605

Scheiner was born in Markt Wald near Mindelheim in Swabia, earlier markgrava ...

would keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar-projection systems. He called these "Heliotropii Telioscopici", later contracted to helioscope

A helioscope is an instrument used in observing the sun and sunspots.

The helioscope was first used by Benedetto Castelli (1578-1643) and refined by Galileo (1564–1642). The method involves projecting an image of the sun onto a white sheet of pa ...

. For his helioscope studies, Scheiner built a box around the viewing/projecting end of the telescope, which can be seen as the oldest known version of a box-type camera obscura. Scheiner also made a portable camera obscura.

In his 1613 book ''Opticorum Libri Sex'' Belgian Jesuit mathematician, physicist, and architect François d'Aguilon

François d'Aguilon (also d'Aguillon or in Latin Franciscus Aguilonius) (4 January 1567 – 20 March 1617) was a Jesuit, mathematician, physicist, and architect from the Spanish Netherlands.

D'Aguilon was born in Brussels; his father was a secret ...

described how some charlatans cheated people out of their money by claiming they knew necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead by summoning their spirits as apparitions or visions, or by resurrection for the purpose of divination; imparting the means to foretell future events; ...

and would raise the specters of the devil from hell to show them to the audience inside a dark room. The image of an assistant with a devil's mask was projected through a lens into the dark room, scaring the uneducated spectators.

By 1620 Kepler used a portable camera obscura tent with a modified telescope to draw landscapes. It could be turned around to capture the surroundings in parts.

Dutch inventor

By 1620 Kepler used a portable camera obscura tent with a modified telescope to draw landscapes. It could be turned around to capture the surroundings in parts.

Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

is thought to have constructed a box-type camera obscura which corrected the inversion of the projected image. In 1622, he sold one to the Dutch poet, composer, and diplomat Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist C ...

who used it to paint and recommended it to his artist friends. Huygens wrote to his parents (translated from French):

German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian

German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian Daniel Schwenter

Daniel Schwenter (Schwender) (31 January 1585 – 19 January 1636) was a German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian.

Biography

Schwenter was born in Nuremberg. He was professor of oriental languages and mathematics at ...

wrote in his 1636 book ''Deliciae Physico-Mathematicae'' about an instrument that a man from Pappenheim

Pappenheim is a town in the Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen district, in Bavaria, Germany. It is situated on the river Altmühl, 11 km south of Weißenburg in Bayern.

History

Historically, Pappenheim was a statelet within Holy Roman Empire. It ...

had shown him, which enabled movement of a lens to project more from a scene through the camera obscura. It consisted of a ball as big as a fist, through which a hole (AB) was made with a lens attached on one side (B). This ball was placed inside two-halves of part of a hollow ball that were then glued together (CD), in which it could be turned around. This device was attached to a wall of the camera obscura (EF). This universal joint

A universal joint (also called a universal coupling or U-joint) is a joint or coupling connecting rigid shafts whose axes are inclined to each other. It is commonly used in shafts that transmit rotary motion. It consists of a pair of hinges lo ...

mechanism was later called a scioptric ball.

In his 1637 book ''Dioptrique'' French philosopher, mathematician and scientist René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

suggested placing an eye of a recently dead man (or if a dead man was unavailable, the eye of an ox) into an opening in a darkened room and scraping away the flesh at the back until one could see the inverted image formed on the retina.

Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer

Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer Mario Bettini

Mario Bettinus (Italian name: Mario Bettini; 6 February 1582 – 7 November 1657) was an Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician and astronomer. The lunar crater Bettinus was named after him by Giovanni Riccioli in 1651.

Biography

Mario ...

wrote about making a camera obscura with twelve holes in his ''Apiaria universae philosophiae mathematicae'' (1642). When a foot soldier would stand in front of the camera, a twelve-person army of soldiers making the same movements would be projected.

French mathematician, Minim friar, and painter of anamorphic art

Anamorphosis is a distorted projection requiring the viewer to occupy a specific vantage point, use special devices, or both to view a recognizable image. It is used in painting, photography, sculpture and installation, toys, and film special e ...

Jean-François Nicéron (1613–1646) wrote about the camera obscura with convex lenses. He explained how the camera obscura could be used by painters to achieve perfect perspective in their work. He also complained how charlatans abused the camera obscura to fool witless spectators and make them believe that the projections were magic or occult science. These writings were published in a posthumous version of ''La Perspective Curieuse'' (1652).

1650 to 1800: Introduction of the magic lantern, popular portable box-type drawing aid, painting aid

The use of the camera obscura to project special shows to entertain an audience seems to have remained very rare. A description of what was most likely such a show in 1656 in France, was penned by the poetJean Loret

Jean Loret (ca 1600-1665) was a French writer and poet known for publishing the weekly news of Parisian society (including, initially, its pinnacle, the court of Louis XIV itself) from 1650 until 1665 in verse in what he called a ''gazette burles ...

, who expressed how rare and novel it was. The Parisian society were presented with upside-down images of palaces, ballet dancing and battling with swords. Loret felt somewhat frustrated that he did not know the secret that made this spectacle possible. There are several clues that this may have been a camera obscura show, rather than a very early magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a si ...

show, especially in the upside-down image and Loret's surprise that the energetic movements made no sound.

German Jesuit scientist Gaspar Schott

Gaspar Schott (German: ''Kaspar'' (or ''Caspar'') ''Schott''; Latin: ''Gaspar Schottus''; 5 February 1608 – 22 May 1666) was a German Jesuit and scientist, specializing in the fields of physics, mathematics and natural philosophy, and known fo ...

heard from a traveler about a small camera obscura device he had seen in Spain, which one could carry under one arm and could be hidden under a coat. He then constructed his own sliding box camera obscura, which could focus by sliding a wooden box part fitted inside another wooden box part. He wrote about this in his 1657 ''Magia universalis naturæ et artis'' (volume 1 – book 4 "Magia Optica" pages 199–201).

By 1659 the magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a si ...

was introduced and partly replaced the camera obscura as a projection device, while the camera obscura mostly remained popular as a drawing aid. The magic lantern can be regarded as a (box-type) camera obscura device that projects images rather than actual scenes. In 1668, Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

described the difference for an installation to project the delightful "various apparitions and disappearances, the motions, changes and actions" by means of a broad convex-glass in a camera obscura setup: "if the picture be transparent, reflect the rays of the sun so as that they may pass through it towards the place where it is to be represented; and let the picture be encompassed on every side with a board or cloth that no rays may pass beside it. If the object be a statue or some living creature, then it must be very much enlightened by casting the sun beams on it by refraction, reflexion, or both." For models that can't be inverted, like living animals or candles, he advised: "let two large glasses of convenient spheres be placed at appropriate distances".

The 17th century Dutch Masters

Dutch Golden Age painting is the painting of the Dutch Golden Age, a period in Dutch history roughly spanning the 17th century, during and after the later part of the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) for Dutch independence.

The new Dutch Republ ...

, such as Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer ( , , #Pronunciation of name, see below; also known as Jan Vermeer; October 1632 – 15 December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period Painting, painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle class, middle-class life. ...

, were known for their magnificent attention to detail. It has been widely speculated that they made use of the camera obscura, but the extent of their use by artists at this period remains a matter of fierce contention, recently revived by the Hockney–Falco thesis

The Hockney–Falco thesis is a theory of art history, advanced by artist David Hockney and physicist Charles M. Falco. Both claimed that advances in realism and accuracy in the history of Western art since the Renaissance were primarily the resul ...

.

German philosopher

German philosopher Johann Sturm

Johann Christoph Sturm (3 November 1635 – 26 December 1703) was a German philosopher, professor at University of Altdorf and founder of a short-lived scientific academy known as the Collegium Curiosum, based on the model of the Florentine A ...

published an illustrated article about the construction of a portable camera obscura box with a 45° mirror and an oiled paper screen in the first volume of the proceedings of the Collegium Curiosum, ''Collegium Experimentale, sive Curiosum'' (1676).

Johann Zahn

Johann Zahn (29 March 1641, Karlstadt am Main – 27 June 1707) was the seventeenth-century German author of ''Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium'' (Würzburg, 1685). This work contains many descriptions and diagrams, illustrati ...

's ''Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium'', published in 1685, contains many descriptions, diagrams, illustrations and sketches of both the camera obscura and the magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a si ...

. A hand-held device with a mirror-reflex mechanism was first proposed by Johann Zahn

Johann Zahn (29 March 1641, Karlstadt am Main – 27 June 1707) was the seventeenth-century German author of ''Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium'' (Würzburg, 1685). This work contains many descriptions and diagrams, illustrati ...

in 1685, a design that would later be used in photographic cameras.

The scientist Robert Hooke presented a paper in 1694 to the Royal Society, in which he described a portable camera obscura. It was a cone-shaped box which fit onto the head and shoulders of its user.

From the beginning of the 18th century, craftsmen and opticians would make camera obscura devices in the shape of books, which were much appreciated by lovers of optical devices.

One chapter in the Conte Algarotti's ''Saggio sopra Pittura'' (1764) is dedicated to the use of a camera ottica ("optic chamber") in painting.

By the 18th century, following developments by Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

and Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, more easily portable models in boxes became available. These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals, including Paul Sandby

Paul Sandby (1731 – 7 November 1809) was an English map-maker turned landscape painter in watercolours, who, along with his older brother Thomas, became one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1768.

Life and work

Sandby was ...

and Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

, whose camera (disguised as a book) is now in the Science Museum in London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

. Such cameras were later adapted by Joseph Nicephore Niepce, Louis Daguerre

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre ( , ; 18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851) was a French artist and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as one of the fathers of photog ...

and William Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE Royal Astronomical Society, FRAS (; 11 February 180017 September 1877) was an English scientist, inventor, and photography pioneer who invented the Salt print, salted paper and calo ...

for creating the first photographs.

Role in the modern age

While the technical principles of the camera obscura have been known since antiquity, the broad use of the technical concept in producing images with a

While the technical principles of the camera obscura have been known since antiquity, the broad use of the technical concept in producing images with a linear perspective

Linear or point-projection perspective (from la, perspicere 'to see through') is one of two types of 3D projection, graphical projection perspective in the graphic arts; the other is parallel projection. Linear perspective is an approximate r ...

in paintings, maps, theatre setups, and architectural, and, later, photographic images and movies started in the Western Renaissance and the scientific revolution. Although Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(Ibn al-Haytham) had already observed an optical effect and developed a pioneering theory of the refraction of light, he was less interested in producing images with it (compare Hans Belting

Hans Belting (born 7 July 1935 in Andernach, Rhine Province) is a German art historian and theorist of medieval and Renaissance art, as well as contemporary art and image theory. He was born in Andernach, Germany, and studied at the universities ...

2005); the society he lived in was even hostile (compare Aniconism in Islam

Aniconism in Islam is the avoidance of images (aniconism) of sentient beings in some forms of Islamic art. Islamic aniconism stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry and in part from the belief that the creation of living forms is God's pr ...

) toward personal images.Hans Belting Das echte Bild. Bildfragen als Glaubensfragen. München 2005,

Western artists and philosophers used the Arab findings in new frameworks of epistemic relevance.An Anthropological Trompe L'Oeil for a Common World: An Essay on the Economy of Knowledge, Alberto Corsin Jimenez, Berghahn Books, 15 June 2013 For example, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

used the camera obscura as a model of the eye, René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

for eye and mind, and John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

started to use the camera obscura as a metaphor of human understanding per se.Philosophy of Technology: Practical, Historical and Other Dimensions P.T. Durbin Springer Science & Business Media The modern use of the camera obscura as an epistemic machine had important side effects for science.Contesting Visibility: Photographic Practices on the East African Coast Heike Behrend transcript, 2014Don Ihde

Don Ihde (; born 1934) is an American philosopher of science and technology.Katinka Waelbers, ''Doing Good with Technologies: Taking Responsibility for the Social Role of Emerging Technologies'', Springer, 2011, p. 77. In 1979 he wrote what is of ...

Art Precedes Science: or Did the Camera Obscura Invent Modern Science? In Instruments in Art and Science: On the Architectonics of Cultural Boundaries in the 17th Century Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, Jan Lazardzig, Walter de Gruyter, 2008

While the use of the camera obscura has waxed and waned, one can still be built using a few simple items: a box, tracing paper, tape, foil, a box cutter, a pencil, and a blanket to keep out the light. Homemade camera obscura are popular primary- and secondary-school science or art projects.

In 1827, critic Vergnaud complained about the frequent use of camera obscura in producing many of the paintings at that year's Salon exhibition in Paris: "Is the public to blame, the artists, or the jury, when history paintings, already rare, are sacrificed to genre painting, and what genre at that!... that of the camera obscura." (translated from French)

British photographer Richard Learoyd

Richard Learoyd (born 1966) is a British contemporary artist and photographer.

Early life and work

Richard Learoyd was born in the small mill town of Nelson, Lancashire, England in 1966. At the age of 15, his mother insisted he take a pinhole p ...

has specialized in making pictures of his models and motifs with a camera obscura instead of a modern camera, combining it with the ilfochrome

Ilfochrome (also commonly known as Cibachrome) is a dye destruction positive-to-positive photographic process used for the reproduction of film transparencies on photographic paper. The prints are made on a dimensionally stable polyester base as o ...

process which creates large grainless prints.

Other contemporary visual artists who have explicitly used camera obscura in their artworks include James Turrell

James Turrell (born May 6, 1943) is an American artist known for his work within the Light and Space movement. Much of Turrell's career has been devoted to a still-unfinished work, ''Roden Crater'', a natural cinder cone crater located outside ...

, Abelardo Morell

Abelardo Morell (born 1948, Havana, Cuba) is a contemporary artist widely known for turning rooms into camera obscuras and then capturing the marriage of interior and exterior in large format photographs. He is also known for his 'tent-camera,' a ...

, Minnie Weisz, Robert Calafiore

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, Vera Lutter

Vera Lutter (born in Kaiserslautern, in 1960) is a German artist based in New York City. She works with several forms of digital media, including photography, projections, and video-sound installations. Through a multitude of processes, Lutter' ...

, Marja Pirilä, and Shi Guorui

Shi or SHI may refer to:

Language

* ''Shi'', a Japanese title commonly used as a pronoun

* ''Shi'', proposed gender-neutral pronoun

* Shi (kana), a kana in Japanese syllabaries

* Shi language

* ''Shī'', transliteration of Chinese Radical 44

...

.

Gallery

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States ...

. A pinhole can be seen to the left of the door.

File:CameraObscuraSanFranciscoCliffHouse.jpg, A freestanding room-sized camera obscura in the shape of a camera. Cliff House, San Francisco

The Cliff House is a neo-classical style building perched on the headland above the cliffs just north of Ocean Beach, in the Outer Richmond neighborhood of San Francisco, California. The building overlooks the site of the Sutro Baths ruins, S ...

File:Camara-obscura-image.JPG, Image of the South Downs

The South Downs are a range of chalk hills that extends for about across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, in the Eastbourne Downland Estate, East Sussex, in the east. ...

of Sussex in the camera obscura of Foredown Tower

Foredown Tower is a former water tower in Portslade, in the city of Brighton and Hove, England, that now contains one of only two operational camera obscuras in southeast England.

Built in 1909 as a water tower for Foredown Hospital, an isolat ...

, Portslade

Portslade is a western suburb of the city of Brighton and Hove, England. Portslade Village, the original settlement a mile inland to the north, was built up in the 16th century. The arrival of the railway from Brighton in 1840 encouraged rapid de ...

, England

File:Camera Obscura.JPG, A camera obscura created by Mark Ellis in the style of an Adirondack mountain cabin, Lake Flower, Saranac Lake, New York

Saranac Lake is a village in the state of New York, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 5,406, making it the largest community by population in the Adirondack Park. The village is named after Upper, Middle and Lower Saran ...

File:Modern Camera Obscura.JPG, A modern-day camera obscura

File:Camera Obscura in Use.JPG, Modern-day camera obscura used indoors

Large public access installations

See also

*Bonnington Pavilion

The Bonnington Pavilion or Hall of Mirrors, now a ruin, is situated in the grounds of the old estate of Bonnington, near New Lanark, overlooking Corra Linn falls on the River Clyde in Lanarkshire, Scotland. Alternative names are the Corra Linn Pa ...

– the first Scottish Camera Obscura, dating from 1708

* Black mirror

''Black Mirror'' is a British anthology television series created by Charlie Brooker. Individual episodes explore a diversity of genres, but most are set in near-future dystopias with science fiction technology—a type of speculative fictio ...

* Bristol Observatory

* Camera lucida

A ''camera lucida'' is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists and microscopists.

The ''camera lucida'' performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist se ...

* History of cinema

The history of film chronicles the development of a visual art form created using film technologies that began in the late 19th century.

The advent of film as an artistic medium is not clearly defined. However, the commercial, public scree ...

* Hockney–Falco thesis

The Hockney–Falco thesis is a theory of art history, advanced by artist David Hockney and physicist Charles M. Falco. Both claimed that advances in realism and accuracy in the history of Western art since the Renaissance were primarily the resul ...

* Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

* Pepper's ghost

Pepper's ghost is an illusion technique used in the theatre, cinema, amusement parks, museums, television, and concerts.

It is named after the English scientist John Henry Pepper (1821–1900) who began popularising the effect with a theatre ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * Hill, Donald R. (1993), "Islamic Science and Engineering",Edinburgh University Press

Edinburgh University Press is a scholarly publisher of academic books and journals, based in Edinburgh, Scotland.

History

Edinburgh University Press was founded in the 1940s and became a wholly owned subsidiary of the University of Edinburgh ...

, page 70.

*Lindberg, D.C. (1976), "Theories of Vision from Al Kindi to Kepler", The University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

, Chicago and London.

*Nazeef, Mustapha (1940), "Ibn Al-Haitham As a Naturalist Scientist", , published proceedings of the Memorial Gathering of Al-Hacan Ibn Al-Haitham, 21 December 1939, Egypt Printing.

* Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics''. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

*Omar, S.B. (1977). "Ibn al-Haitham's Optics", Bibliotheca Islamica, Chicago.

*

*

*Lefèvre, Wolfgang (ed.) ''Inside the Camera Obscura: Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image.'' Max Planck Institut Fur Wissenschaftgesichte. Max Planck Institute for the History of Scienc*

Burkhard Walther Burchard (and all variant spellings) may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People

* Burchard (name), Burchard and all related spellings as a given name and surname

* Burckhardt, or (de) Bourcard, a family of the Basel patriciate

* Burchard-Bélaváry family, an a ...

, Przemek Zajfert: ''Camera Obscura Heidelberg. Black-and-white photography and texts. Historical and contemporary literature''. edition merid, Stuttgart, 2006,

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Camera Obscura Audiovisual introductions in 1502 17th-century neologisms Optical toys Optical devices Artistic techniques Precursors of photography Precursors of film